Both visual and proprioceptive information contribute to the accuracy of limb movement, but the mechanism of integration of these different modality signals for movement control and learning remains controversial. We aimed to elucidate the mechanism of multisensory integration for motor adaptation by evaluating single-trial adaptation (i.e., aftereffect) induced by visual and proprioceptive perturbations while male and female human participants performed reaching movements.

Keywords: divisive normalization, motor learning, multisensory integration, reaching movement

Abstract

Both visual and proprioceptive information contribute to the accuracy of limb movement, but the mechanism of integration of these different modality signals for movement control and learning remains controversial. We aimed to elucidate the mechanism of multisensory integration for motor adaptation by evaluating single-trial adaptation (i.e., aftereffect) induced by visual and proprioceptive perturbations while male and female human participants performed reaching movements. The force-channel method was used to precisely impose several combinations of visual and proprioceptive perturbations (i.e., error), including an instance when the directions of perturbation in both stimuli opposed each another. In the subsequent probe force-channel trial, the lateral force against the channel was quantified as the aftereffect to clarify the mechanism by which the motor adaptation system corrects movement in the event of visual and proprioceptive errors. We observed that the aftereffects had complex dependence on the visual and proprioceptive errors. Although this pattern could not be explained by previously proposed computational models based on the reliability of sensory information, we found that it could be reasonably explained by a mechanism known as divisive normalization, which was the reported mechanism underlying the integration of multisensory signals in neurons. Furthermore, we discovered evidence that the motor memory for each sensory modality developed separately in accordance with a divisive normalization mechanism and that the outputs of both memories were integrated. These results provide a novel view of the utilization and integration of different sensory modality signals in motor adaptation.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT The mechanism of utilization of multimodal sensory information by the motor control system to perform limb movements with accuracy is a fundamental question. However, the mechanism of integration of these different sensory modalities for movement control and learning remains highly debatable. Herein, we demonstrate that multisensory integration in the motor learning system can be reasonably explained by divisive normalization, a canonical computation, ubiquitously observed in the brain (Carandini and Heeger, 2011). Moreover, we provide evidence of a novel idea that integration does not occur at the sensory information processing level, but at the motor execution level, after the motor memory for each sensory modality is separately created.

Introduction

The motor system sends a motor command to the motor apparatus, while predicting the sensory consequence by a forward model (Wolpert et al., 1995). The difference between the actual and predicted sensory information (i.e., sensory prediction error) is used to update and refine the motor command in subsequent movements, which plays a significant role in adapting the movement to a novel condition and also performing consistent movement (Shadmehr et al., 2010). Experimental paradigms with visuomotor rotation (Krakauer et al., 2000) or force-field perturbation (Lackner and DiZio, 1994; Shadmehr and Mussa-Ivaldi, 1994), have clarified how the motor system uses vision and proprioception to calculate sensory prediction errors for motor adaptation. The contribution of the information provided by each sensory modality has been also investigated by eliminating visual information (Franklin et al., 2007), recruiting blind (DiZio and Lackner, 2000) and deafferent subjects (Bernier et al., 2006; Yousif et al., 2015), or disturbing proprioceptive information (Pipereit et al., 2006) with the help of such experimental paradigms.

However, there is controversy regarding the method of integration of visual and proprioceptive information that are received simultaneously. Earlier studies have reported that sensory signals in different modalities are optimally integrated to estimate the size of an object (haptic and vision; Ernst and Banks, 2002) and to locate the perceived position of a limb (proprioception and vision; van Beers et al., 1999, 2002). A simple explanation would be that the motor adaptation system estimates the error size by a similar optimal integration mechanism. However, such correspondence between the perception of error size and error processing for motor adaptation is not necessarily guaranteed because motor adaptation could progress without awareness of movement errors (Kagerer et al., 1997; Mazzoni and Krakauer, 2006; Hirashima and Nozaki, 2012; Hayashi et al., 2016).

Furthermore, this mechanism cannot explain the empirical results obtained when several errors are imposed during reaching movements. The optimal integration model predicts that the movement correction induced by error (i.e., aftereffect), which could reflect the size of the integrated error, linearly increases with an increase in the error size. However, the aftereffect does not increase but instead saturates with an increase in the size of an error (Wei and Körding, 2009; Marko et al., 2012; Kasuga et al., 2013). Wei and Körding (2009) attempted to explain the aftereffect saturation of visual errors by assuming that the increased dissociation between visual and proprioceptive information decreases the relevance of visual error. However, Marko et al. (2012) demonstrated that congruence between visual and proprioceptive errors (i.e., maximal relevance of error) did not eliminate the saturation effect and posited that the saturation effect is an inherent characteristic of the motor adaptation system. They also proposed a simpler model in which visual and proprioceptive errors independently contributed to the aftereffect.

Therefore, different mechanisms seem necessary to solve these inconsistencies. We speculated that divisive normalization (Carandini and Heeger, 2011) is one such mechanism. It suggests that neuronal activity is normalized by the pooled activities of neurons and is considered to be canonical neural computation in the brain. Ohshiro et al. (2011, 2017) have recently demonstrated that the multimodal (visual and vestibular) neuronal-activity pattern can be explained by the divisive normalization mechanism: the stimulus for one of the modalities, even if it failed to elicit any response by the multisensory neurons, could suppress the response to the stimulus for another modality if both stimuli are simultaneously presented (cross-modal suppression). If the computation based on divisive normalization in the neuronal-circuit level influences the adaptation behavior, there is a possibility that the motor adaptation pattern induced by various combinations of visual and proprioceptive errors should also follow the pattern predicted by the divisive normalization mechanism. This study explores this possibility by examining the mechanism of aftereffect modulation for various combinations of visual and proprioceptive errors during reaching movements.

Materials and Methods

Divisive normalization model.

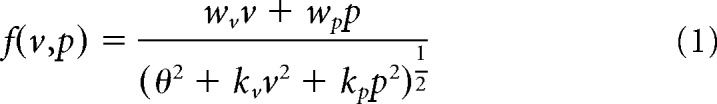

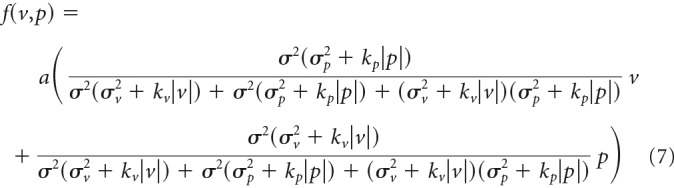

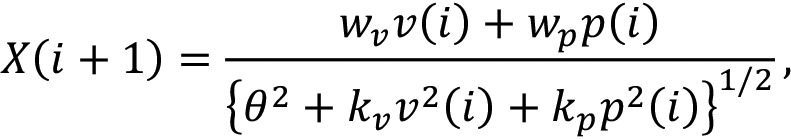

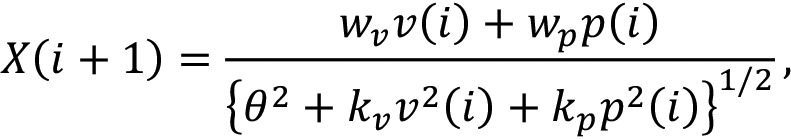

As a framework for the integration of visual and proprioceptive information in the motor adaptation system, this study considered the following divisive normalization model (Webb et al., 2014; Ren et al., 2016):

|

where f(v, p) is the aftereffect induced by the visual (v) and proprioceptive (p) error (or perturbation) imposed during a reaching movement and wv, wp, kv, wp, and θ are constants. θ can be set to unity (i.e., θ = 1) without loss of generality by dividing both the numerator and denominator with θ and by replacing w/θ and k/θ2 with w and k, respectively.

Based on the previous study showing that divisive normalization can explain the activity pattern of multisensory neurons integrating vision and vestibular signals (Ohshiro et al., 2011, 2017) and vision and proprioception (Shi et al., 2013), we speculated that such computation in the neuronal-circuit level should also be reflected in behavior. In addition, this model has several notable characteristics to elucidate behavior in motor adaptation. First, the presence of the normalization term (the denominator in Eq. 1) might naturally explain why the aftereffect does not necessarily increase with the error size without introducing additional mechanisms; the larger error should increase the normalization term, which can prevent the aftereffect from increasing further. Second, the model assumes the weighted linear summation of visual and proprioceptive error information; the structure of the model is similar to that of optimal integration model (van Beers et al., 1999, 2002; Ernst and Banks, 2002; for details, see Results). Indeed, it has been argued that a neural network with divisive normalization can integrate multisensory information (Seilheimer et al., 2014).

To experimentally determine the shape of f(v,p) (Eq. 1), we need to precisely impose various combinations of visual and proprioceptive errors with a wide range of magnitudes. The conventional experiments using force field and visual rotation are not appropriate for this purpose because the size of the error should randomly vary among trials. Thus, we attempted to use the force-channel method (Scheidt et al., 2000) to precisely and independently impose visual and proprioceptive errors by deviating the visual cursor and hand movement directions from a target direction (see the section of Experiments 1 and 2).

General experimental setting.

Thirty-four right-handed participants (26 male, 8 female; aged 20–31 years) volunteered to participate in the three experiments. Before the experiments started, we fully explained the experimental procedures, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The ethics committee of the University of Tokyo approved the experiments.

The participants performed reaching movements while holding a manipulandum (KINARM End-point Lab, BKIN Technologies). To reduce unwanted wrist movement and postural fluctuation, their arms were constrained by a brace and supported in a horizontal plane with a spring sling. The green target (diameter: 10 mm) was located 10 cm from the start position immediately in front of the participant. After 0.5–0.7 s, the target color turned to magenta, which was the “go” cue. The participants were asked to move the handle of the KINARM robot straight toward the target as smoothly as possible. In Experiments 1 and 3, the cursor (diameter: 10 mm) representing the position of the handle was continuously visible, whereas the cursor was visible only after the reaching movement was complete in Experiment 2. At the end of each trial, a warning message (“fast” or “slow”) appeared when the movement speeds were too fast (>450 mm/s) or too slow (<250 mm/s). The participants maintained the hand position at the end of the movement until the robot automatically returned the handle to the starting position (for 1.5 s). The force-channel method in the perturbation trial (see next section) could not allow the participants to correct the movement trajectories. Thus, the cursor could never reach the target under the presence of visual perturbations in Experiments 1 and 3. Similarly, in Experiment 2, the participants were unable to know the movement distance until completion of the movement. The participants practiced so that they could terminate the movement at the appropriate distance (the actual movement distance was 9.85 ± 0.1 cm).

Experiments 1 and 2.

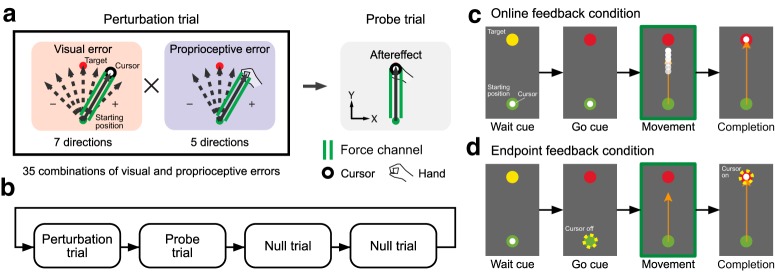

In Experiment 1 (10 participants: 8 male, 2 female; aged 21–25 years) and Experiment 2 (10 participants: 6 male, 4 female; aged 21–31 years), we examined a single-trial motor adaptation induced by 35 combinations of 7 visual (±45, ±30, ±15, and 0°; Fig. 1a, red) and 5 proprioceptive perturbations (±30, ±15, and 0°; 1a, blue). These perturbations were applied by constraining the hand trajectory in a straight line using the force-channel method. The force channel was created by a virtual spring (6000 N/m) and dumper [100 N/(m/s)] in the perpendicular direction to the straight path of the movement. In the following probe trial, the lateral force against the force channel was measured to evaluate the aftereffect (Fig. 1a, gray). One set consisted of a perturbation trial (1 of 35 combinations was pseudorandomly selected) and a probe trial followed by two ordinary null trials (without the force channel) to washout the adaptation effect (Fig. 1b). The cursor was always visible (online feedback: Fig. 1c) in Experiment 1, whereas the cursor was only visible after the completion of the reaching movement (endpoint feedback: Fig. 1d) in Experiment 2.

Figure 1.

Procedures of Experiments 1 and 2. a, Participants made reaching movements toward a front target (distance, 10 cm). In the perturbation trial, the force channel was used to provide a visual and/or proprioceptive perturbation. There were 35 combinations of perturbations in total (7 visual perturbations from −45 to 45° and 5 proprioceptive perturbations from −30 to 30°). In the subsequent probe trial, the force channel was used to measure the aftereffect. b, The perturbation and probe trials were followed by two null trials to washout the effect of adaptation. This small block was repeated. c, In Experiment 1 (online feedback condition), the cursor was always visible during the reaching movement. d, In Experiment 2 (endpoint feedback condition), the cursor disappeared at movement onset and reappeared only after completion of the movement.

Experiment 3.

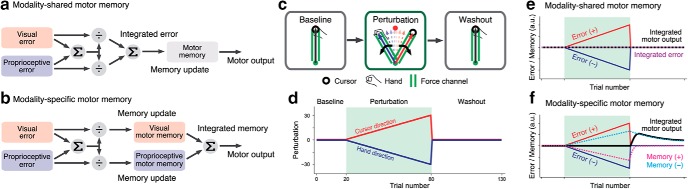

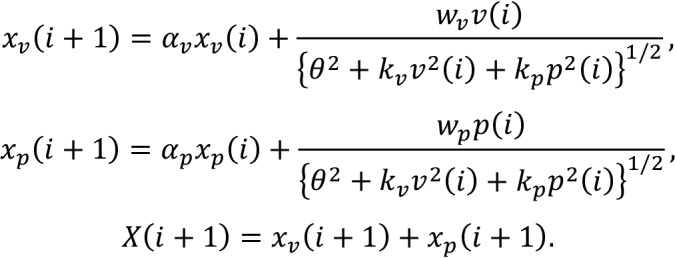

Experiment 3 aimed to determine the stage at which the visual and proprioceptive information is integrated. There are two potential models: the modality-shared motor memory model (Fig. 2a) or the modality-specific motor memory model (Fig. 2b). The modality-shared motor memory model (Fig. 2a) assumes that visual and proprioceptive sensory prediction errors are used to estimate a single integrated error according to a divisive normalization mechanism, and this integrated error is used for updating motor memory. According to Equation 1, this update process can be expressed as follows:

|

where X(i) is the motor memory in the ith trial and α is a retention constant.

Figure 2.

Possible integration scheme and the procedure of Experiment 3. In the modality-shared motor memory model (a), visual and proprioceptive errors are integrated by the divisive normalization mechanism to obtain the integrated error information. Motor memory is updated by the integrated error. In contrast, in the modality-specific motor memory model (b), visual and proprioceptive memories are independently created. c, d, Experiment 3 was designed to determine which integration scheme was more likely. After 20 force-channel trials to the forward target, gradually increasing visual and proprioceptive perturbations were imposed in the opposite direction (60 trials). This perturbation phase was followed by a washout phase in which the force-channel trials to the forward target were repeated (50 trials). The prediction of lateral force during the washout phase by the modality-shared motor memory model (e; Eq. 2) and by the modality-specific motor memory model (f; Eqs. 3–5). The modality-specific motor memory could exhibit the emergence of aftereffect (i.e., motor output) during the washout phase only if the retention constants (αp and αv in Eqs. 3 and 4) differed sufficiently.

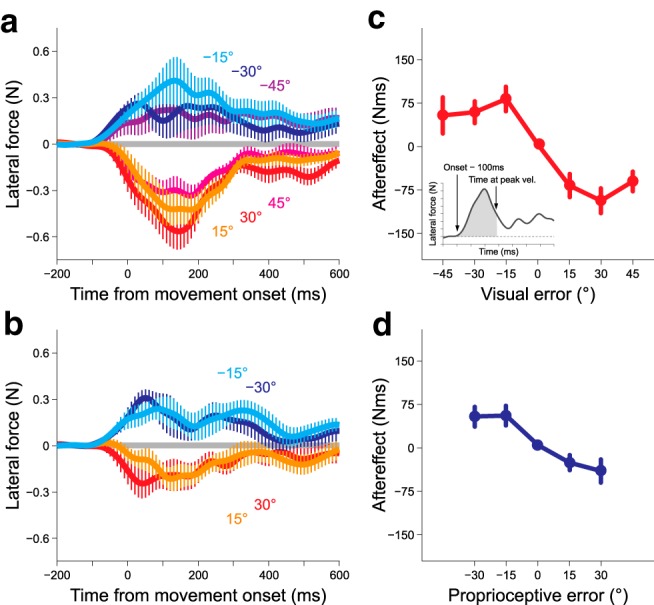

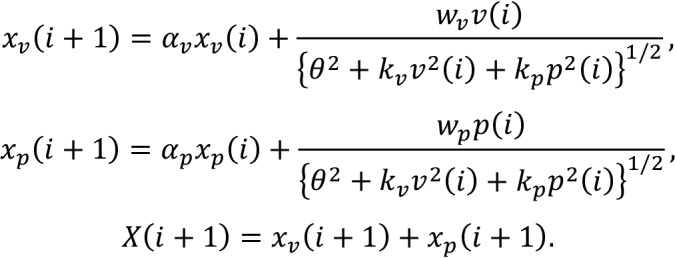

In contrast to this ordinary interpretation of multisensory integration, the modality-specific motor memory model (Fig. 2b) assumes that the motor memories of each modality are separately updated, and then the outputs from these motor memories are integrated. This update process can be expressed as follows:

|

|

where xv(i) and xp(i) are the motor memory for vision and proprioception, respectively, αv and αp are their retention constants, and X(i) is the total amount of motor memory.

Notably, the modality-shared motor memory model has only one retention constant, whereas the modality-specific motor memory model has two different retention constants. If the two retention constants in the modality-specific motor memory model are similar, it is challenging to discriminate between the two models by merely observing the X(i) (indeed, when αv = αp = α, substituting Eqs. 3 and 4 for Eq. 5 yields Eq. 2). However, if the difference between αv and αp is sufficiently large, the trial-dependent behavior of X(i) should contain the influence of two retention constants.

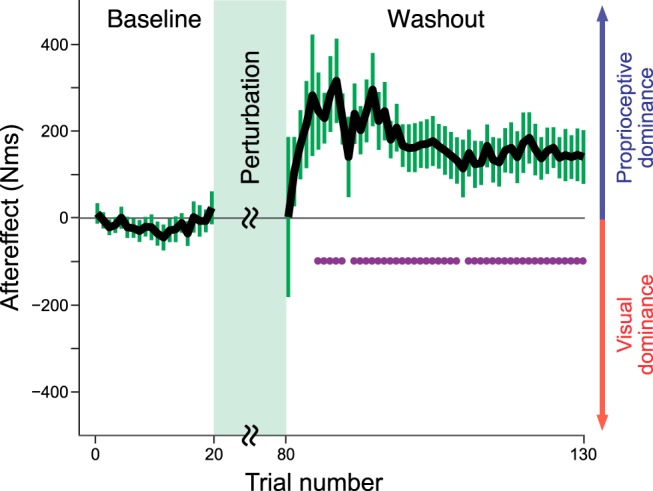

On the assumption that both retention constants were different, we designed Experiment 3 to determine which model was more likely. Fourteen participants (12 male, 2 female; aged 20–25 years) performed 130 reaching movements (Fig. 2c,d). After being familiarized with the procedures, they performed reaching movements with the force channel in the baseline session (20 trials). The participants were then simultaneously exposed to the visual and proprioceptive perturbations in the perturbation session (60 trials). The degrees of perturbation were gradually increased at a rate of 0.5–30°. The directions of the perturbations were opposite and counterbalanced across the participants. In the subsequent washout session, they again performed reaching movements with the force channel (50 trials). The participants were instructed to aim toward the frontal target consistently throughout the experiment.

In both models (Fig. 2e,f), the aftereffect immediately after the completion of the perturbation phase is expected to be almost absent or small because the perturbations are imposed in the opposite directions. However, both models provide completely different predictions during the subsequent washout phase if the retention constants αp and αv in Equations 3 and 4 differ sufficiently. In the modality-shared motor memory model, the aftereffect should remain absent or merely decay during washout trials (Fig. 2e). In contrast, the modality-specific motor memory model should develop modality-specific motor memories in the opposite directions (Fig. 2f). If the retention constants (αp and αv) are different, the time-constant of trial-dependent decay should differ between the memories, and resultantly the motor memory of the slower modality could emerge as the washout trials progress (Fig. 2f). It should be noted again that if the differences in the retention constants are small such behavior cannot be observed.

Data analysis.

The position and force data of the handle were sampled at a rate of 1000 Hz and filtered by a fourth-ordered zero-lag Butterworth filter with cutoff a frequency of 10 Hz. The position of the handle was numerically differentiated to obtain the handle velocity. We quantified the aftereffect in the probe trials as the integrated lateral force Fx(t) over the time interval (i.e., force impulse) from the force onset to the time at the peak handle velocity (T). Theoretically, this measure is almost equivalent to the possible lateral handle velocity vx(t) that could be observed if the force channel is absent (vx(T) ∼ ∫0TFx(t)dt). Because the peak handle velocity toward the target in the probe trial vy(T) was always almost constant, the movement direction at the time T (arctan [vx(T)/vy(T)]) can be approximated by the force impulse ∫0TFx(t)dt, because the arctan [vx(T)/vy(T)] ∼ vx(T)/vy(T) ∼ ∫0TFx(t)dt. Thus, the force impulse can be regarded as the movement direction evaluated in the conventional probe null trial (Kasuga et al., 2013). This guaranteed that the aftereffect pattern we observed should not depend on this measure. We also quantified the amount of online feedback force in the perturbation trials as the integrated lateral force over the time interval from the time at the peak handle velocity to movement termination.

Results

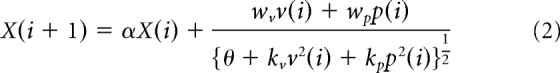

Aftereffects to each of visual and proprioceptive error

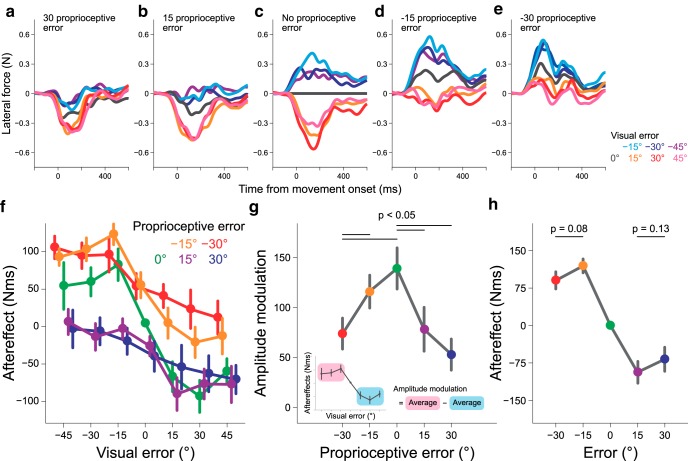

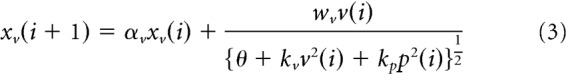

Figure 3 illustrates the evolvement of lateral force with the movement time in the probe trials after only visual (Fig. 3a) or proprioceptive perturbation (Fig. 3b) was imposed. The presence of an aftereffect was confirmed as the lateral force in the direction opposite to the error imposed in the preceding perturbation trial. The aftereffect was quantified as the integrated lateral force over the time interval from the force onset to the time at the peak hand velocity (i.e., feedforward component; Fig. 3c, inset). Notably, not only the visual (Fig. 3c; one-way repeated-measures ANOVA, F(6,54) = 21.979, p = 6.101 × 10−13), but also the proprioceptive perturbation (Fig. 3d; F(4,36) = 18.861, p = 1.934 × 10−8) could elicit aftereffects, although the cursor safely reached the target, indicating that the proprioceptive sensory prediction error was also used for motor adaptation (Pipereit et al., 2006; Franklin et al., 2007). Furthermore, as reported in previous studies (Körding and Wolpert, 2004; Wei and Körding, 2009; Marko et al., 2012; Kasuga et al., 2013), the aftereffect did not increase linearly with the size of perturbation.

Figure 3.

Aftereffects of visual or proprioceptive perturbation in Experiment 1. Time series of the lateral force exerted against the force channel in the probe trial after either visual (a) or proprioceptive perturbation (b) was imposed. The relationship between the aftereffect and the size of the visual (c) or proprioceptive (d) error. The aftereffects were quantified by the integrated lateral force from the force onset to the time of peak velocity (c, inset). The error bars represent the SE across participants.

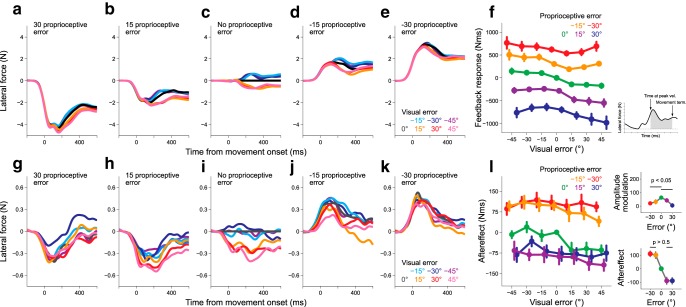

Aftereffects of combinations of visual and proprioceptive errors

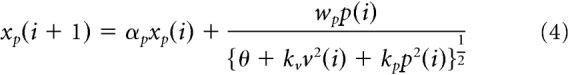

Figure 4a–e illustrates the modulation of the lateral force induced by visual perturbation with additional proprioceptive perturbation. As indicated in Figure 4c, the positive and negative visual perturbations induced negative and positive lateral force (aftereffects), respectively. However, when +30° proprioceptive perturbation was additionally imposed (Fig. 4a), the aftereffect curves for the negative visual perturbations (−15, −30, −45°) were considerably suppressed, whereas the aftereffect curves for the positive visual perturbation (15, 30, 45°) were only slightly altered. The suppression of the lateral force for the opposite visual and proprioceptive perturbation directions and the relatively unchanged lateral force for the same perturbation directions was widely observed when the other amounts of proprioceptive perturbations (−30, −15, and 15°) were additionally imposed (Fig. 4a–e).

Figure 4.

Aftereffects when various combinations of visual and proprioceptive perturbations were applied (Experiment 1). Each panel presents the lateral force exerted against the force channel in the probe trials after seven different visual perturbations were imposed [proprioceptive perturbation = 30° (a), 15° (b), 0° (c), −15° (d), −30° (e)]. f, The dependence of the aftereffect on the size of the visual error. Each line represents the aftereffect when different proprioceptive errors were simultaneously imposed. g, The presence of proprioceptive error decreased the amplitude of the aftereffect modulation of the visual error size. The amplitude was calculated as the difference between the aftereffects of positive and negative visual perturbations (inset). h, Even when the visual and proprioceptive errors were identical, saturation of the aftereffect with the error size was still observed. The error bars represent the SE across participants.

Figure 4f demonstrates the aftereffects of all 35 combinations of visual and proprioceptive perturbations. There was a significant interaction between visual and proprioceptive perturbations (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, F(24,216) = 3.479, p = 5.233 × 10−7), indicating that the effect of proprioceptive perturbation on visual perturbation was not simply additive. Figure 4f also suggests that the degree of modulation with visual perturbation size (i.e., the amplitude of each line) decreased with additional proprioceptive perturbations. To evaluate the size of the modulation, we calculated the difference between the aftereffects for positive visual perturbations (15, 30, and 45°) and those for negative visual perturbations (−15, −30, and −45°; Fig. 4g). A one-way repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that the size of the modulation significantly differed between the size of the proprioceptive perturbations (F(4,36) = 10.27, p = 1.518 × 10−7). A post hoc test revealed that the size of the modulation significantly decreased with the size of the additional proprioceptive perturbation (Fig. 4g; p < 0.05 by Bonferroni–Holm correction).

In the present experiment, there were five conditions in which the visual perturbation was identical to the proprioceptive perturbation (i.e., 0, ±15, ±30°). In these conditions, the relevance of the visual error was perfectly maintained, predicting that the aftereffects were not saturated with the size of the error (Wei and Körding, 2009). However, as indicated in Figure 4h, saturation of the aftereffects was still observed; the size of the aftereffect for ± 30° was not larger than that for ±15° (−30° vs −15°, t(9) = 1.934, p = 0.0851; 30° vs 15°, t(9) = 1.631, p = 0.1372, respectively).

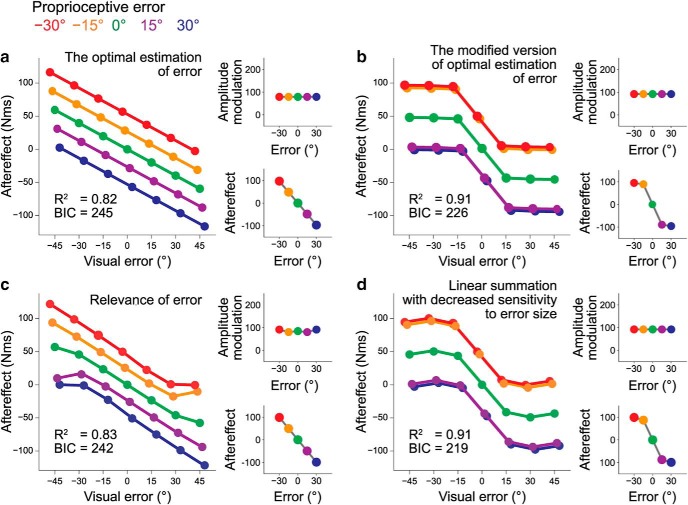

Aftereffect pattern predicted by various computational models

Divisive normalization

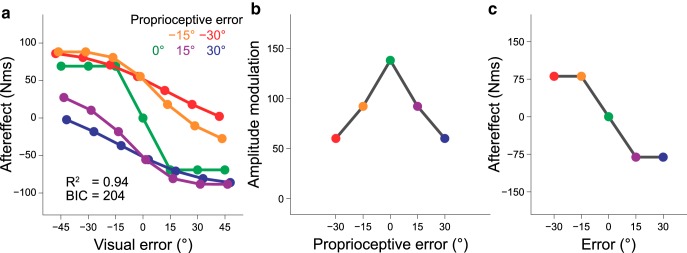

First, we attempted to determine whether the divisive normalization model (Eq. 1) could reasonably explain our results. Figure 5a indicates f(v,p) obtained by fitting the model to the data using the least square method (R2 = 0.9423, wv = 97.61, wp = 151.1, kv = 1.99, kp = 7.73). Notably, this model captured the remarkable features of the experimental results. First, the size of the aftereffect did not linearly increase with the size of the error due to the presence of a normalization factor (Figs. 4f, 5a). Second, the size of the aftereffect modulation by the visual error decreased with the size of the proprioceptive error (Figs. 4g, 5b). Third, the relevance of the error was not related to the saturation of the aftereffect with the error size (Figs. 4h, 5c). As described below, other models cannot reproduce these features and this model provides the smallest BIC (Bayesian information criterion: 204).

Figure 5.

The divisive normalization model to explain the experimental results. a, The divisive normalization model (Eq. 1) fitted to the experimental data using the least-square method reproduced the complicated pattern of the aftereffect. The model also reproduced the reduction in the amplitude modulation with the proprioceptive perturbation (b) and the saturation of the aftereffect with the error size (c).

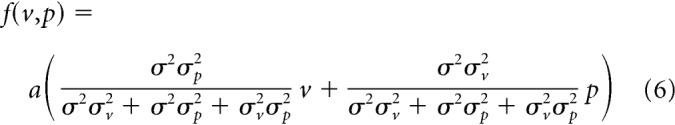

The optimal estimation of the error

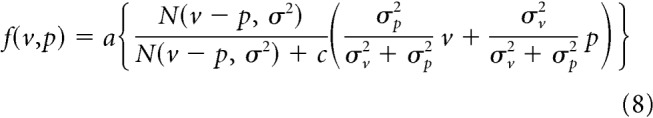

Previous studies (van Beers et al., 1999, 2002) have shown that the hand location is optimally estimated using visual and proprioceptive information. Applying the same mechanism leads to the optimally estimated hand location (h) as follows: h = p, where v and p are the visual and proprioceptive errors, and σv2 and σp2 are their signal uncertainties (variance). We further considered that the motor system corrects the movement direction by integrating the estimated hand location with the predicted hand location (Burge et al., 2008; Wei and Körding, 2010). If the predicted hand location is unbiased and its variance is σ2, the aftereffect f(v,p) should be expressed as (a is a constant) follows:

|

If the uncertainty of the sensory signal (σv2 and σp2) and that of prediction (σ2) are constant, f(v,p) is linearly increased with the visual and proprioceptive errors, which was inconsistent with the experimental data (Fig. 4f–h). Indeed, this model did not fit the data well (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

The results of data fitting by various computational models. We fitted the results of Experiment 1 (Fig. 4f) with four different models: (a) the optimal estimation of the error (Eq. 6; σ2 = 246.55, σv2 = 6.28, σp2 = 4.38, a = 3.25), (b) modified version of the optimal estimation of the error (Eq. 7; σ2 = 4.15 × 10−4, σv2 = 10.05, σp2 = 23.93, kv = 8.89, kp = 7.96, a = 1.03 × 106), (c) relevance of the error (Eq. 8; σv2 = 9.00, σp2 = 8.25, c = 1.93 × 10−4, a = 3.32), and (d) linear summation with decreased sensitivity to the error size (Eq. 9; λv = 4.80, λp = 5.47, τv = 3.51 × 10−2, τp = 4.04 × 10−2). The right top and bottom for each graph, respectively, indicate the amplitude modulation with the proprioceptive error (Fig. 4g) and how the aftereffects were modulated with the error size when the visual and proprioceptive error sizes were identical (Fig. 4h).

The modified version of the optimal estimation of the error

The uncertainty of the signal could be increased with the signal intensity (Jones et al., 2002; Goris et al., 2014). If the standard deviation of the signals linearly increases with the mean signal intensity, the aftereffect can be represented as follows:

|

where a, σ2, σv2, σp2, kv, and kp are constants. This model can reproduce the saturation of the aftereffect with the size of the error (Fig. 6b). However, this model is unable to explain the experimental result that size of the modulation with the visual error becomes smaller as the size of the proprioceptive error is increased (Fig. 4g): as the proprioceptive error becomes greater, the motor system should have relied on the visual error, which might have increased the size of modulation. Indeed, the best fit model did not reproduce the experimental results (Fig. 6b).

Relevance of the error

When receiving different sensory signals (e.g., vision and sound for spatial localization), a fundamental problem is whether these signals should be integrated or not. If these two signals are not related to each other, the integration should not work well (Ernst, 2007; Körding et al., 2007). Based on this idea, Wei and Körding (2009) considered that the motor system should ignore the visual error when the visual error size was greater because greater visual error produces greater difference between vision and proprioception, and this difference might reduce the relevance of the visual error. According to this idea, they proposed a model in which the relevance of the visual error determines the aftereffect. Their model can be formulated as follows:

|

where N(v − p, σ2) is the normal distribution function with mean (v − p) and variance (σ2 = σv2 + σp2) and a and c are constants. Figure 6c demonstrates the pattern of aftereffect fit by this model. This model nicely reproduced the saturation of the aftereffect with the error size. However, the aftereffect is linearly increased with the size of the error when the sizes of the visual and proprioceptive errors are identical (i.e., if v = p = e, then f(v,p) = e) which was inconsistent with our results (Fig. 4h).

Linear summation with decreased sensitivity to the error size

Marko et al. (2012) proposed a mechanism in which visual and proprioceptive memories are independently processed and then linearly integrated (summed). They also assumed that the sensitivity of each memory to the size of the error is decreased with the size of the error:

where λv, λp, τv, and τp are positive constants. Figure 6d indicates the best-fit model. Because the influence of the visual and proprioceptive errors is additive, the five curves in Figure 6d are in parallel, which was again inconsistent with our experimental results (Fig. 4f–h).

As described, the previously proposed models did not qualitatively explain the aftereffect patterns. Furthermore, the divisive normalization model has the smallest BIC (Figs. 5, 6), suggesting that this is the most appropriate model considered in the present study.

Effects of the presence and absence of online visual errors on the aftereffects

In Experiment 1, the participants were exposed to visual and proprioceptive errors during movement. Because multisensory integration can occur during movement (Crevecoeur et al., 2016; Scott, 2016; Oostwoud Wijdenes and Medendorp, 2017), the sensorimotor system can automatically generate online feedback responses to multisensory errors. Previous studies have suggested that the feedback responses function as a teaching signal for motor adaptation (Kawato et al., 1987; Albert and Shadmehr, 2016). Thus, it is possible that the divisive normalization pattern in the aftereffects could reflect the feedback responses in the preceding perturbation trial. To examine this possibility, we quantified the feedback response as the integrated lateral force over the time interval from the time at the peak handle velocity to movement termination (i.e., feedback component; Fig. 7a–e). The feedback responses were modulated with the visual error size regardless of the additional proprioceptive error size (Fig. 7a–e). However, the degree of modulation of the feedback response with visual perturbation size seems relatively unchanged by the additional proprioceptive perturbation (Fig. 7f), which was contrasted with that of the aftereffect (Fig. 4f). The difference was reflected by smaller values of kv and kp obtained by fitting the data with Equation 1 (R2 = 0.9780, wv = 3.20, wp = 24.66, kv = 4.247 × 10−15, and kp = 9.068 × 10−5). The smaller contribution of the normalization factor (i.e., kv and kp are small) indicates that the divisive normalization model is not necessarily appropriate to explain the feedback response behavior and the aftereffect pattern explained by the divisive normalization model cannot be explained by the feedback response (i.e., the possible teaching signal) in the previous perturbation trial.

Figure 7.

The online feedback response in Experiment 1 and the aftereffect (Experiment 2). a–e, g–k, The lateral force exerted against the force channel in the perturbation trial (Experiment 1) and that in the probe trials (Experiment 2), respectively. Each line represents the data for seven different visual perturbations [proprioceptive perturbation = 30° (a, g), 15° (b, h), 0° (c, i), −15° (d, j), −30° (e, k)]. f, l, The dependence of the feedback response (f) and that of the aftereffect (l) on the size of the visual perturbation. Each line represents the data for different proprioceptive perturbations. The feedback response was quantified by the integrated force from the time of peak hand velocity to movement offset (f, inset). The right top and bottom for l, respectively, indicate the amplitude modulation with proprioceptive error (Fig. 4g) and how the aftereffects were modulated with the error size when the visual and proprioceptive error sizes were identical (Fig. 4h). The error bars represent the SE across participants.

However, it should be noted that the feedback responses among the different proprioceptive perturbations could not be directly compared because the movement directions were different. Thus, the difference in the pattern between the aftereffect (Fig. 4f) and the feedback response (Fig. 7f) cannot be solely ascribed to the involvement of different mechanisms. To further investigate this issue, we performed Experiment 2 in which the cursor was only visible immediately after movement completion (the endpoint visual feedback; Fig. 1d). As the visual information was not available during reaching movements, the online feedback response to visual perturbation was absent. Thus, the divisive normalization pattern did not exist in the modulation pattern of the online feedback response. Nevertheless, the aftereffect in the next probe trial was modulated with the endpoint visual error size, and the aftereffects modulation pattern was well explained by a divisive normalization mechanism (R2 = 0.9403, wv = 2.902, wp = 34.90, kv = 0.0055, and kp = 0.1434; Fig. 7g–l), indicating that the offline process integrating visual and proprioceptive error information was partly responsible for the divisive normalization pattern in the aftereffect in Experiment 1 (Fig. 4f).

The stage of integration of visual and proprioceptive information

A remaining question was at which stage the visual information and proprioceptive information are integrated. Experiment 3 was designed to determine which model was more likely (Fig. 2a,b). Participants reached toward a frontal target while receiving gradually increasing visual and proprioceptive perturbations in the opposite directions for 60 trials (perturbation phase). We measured the aftereffects during the following 50 force-channel trials toward the same front target (washout phase: both visual and proprioceptive perturbations were turned off) by quantifying the lateral force against the force channel. The modality-shared motor memory model and the modality-specific motor memory model should provide different predictions (Fig. 2e,f).

As expected from the opposite directions of the visual and proprioceptive perturbations, significant aftereffects were absent in the beginning of the washout trials (Fig. 8; t(13) = 0.013, p = 0.9898). However, as the washout phase progressed, the aftereffect began to emerge in the direction opposite to that of the proprioceptive perturbation (i.e., in the direction of the visual perturbation), reached a maximum, and then decayed (Fig. 8). Therefore, the experimental result supported the modality-specific motor memory model (Figs. 2b,f, 8). A similar trial-dependent aftereffect pattern could be reproduced by the state space model implementing the memory integration mechanism (Fig. 8-1).

Figure 8.

Aftereffect during washout phase in Experiment 3. The experimental results indicated that the aftereffect at the beginning of the washout phase was indistinguishable from that of the baseline trials. However, as the trials progressed, an aftereffect that was significantly greater than zero appeared and then decayed. Notably, the state space model (Eqs.3–5) could reproduce this trial-dependent pattern (Figure 8-1). The error bars represent the SE across participants. The purple dots indicate the trials with aftereffects significantly greater than 0 (as determined by a t test with false discovery correction).

Simulation result of the modality-specific motor memory model. The results of Experiment 3 indicate that vision and proprioception are likely to have distinct motor memories. One possible model is that each motor memory (xv and xp are motor memories for vision and proprioception, respectively) is updated by the divisively normalized error and the outputs are integrated as follows:

|

When the single trial adaptation is measured (xv(i) = xp(i) = 0), the aftereffect should be

|

which is equivalent to Eq. 1 in the main text. This model was used to simulate the trial dependent pattern of aftereffect in Experiment 3 (a). The parameters used for this simulation can reproduce the single trial aftereffects in Experiment 1 (b). Download Figure 8-1, EPS file (224.4KB, eps)

Discussion

We investigated the utilization of visual and proprioceptive information in motor adaptation by imposing various perturbation combinations using a force-channel method. The present results indicate that the aftereffect depended on the visual and proprioceptive errors in a complicated manner (Figs. 3, 4), and this pattern was reasonably explained by the divisive normalization mechanism (Fig. 5). Furthermore, we demonstrated that the visual and proprioceptive motor memories were created independently (Figs. 2b, 8).

Comparison with previously proposed mechanisms of multisensory signal integration

Multisensory information is optimally integrated according to signal reliability (Ernst and Banks, 2002; Körding et al., 2007). van Beers et al. (1999, 2002) demonstrated that the hand position is optimally estimated by integrating visual and proprioceptive information. It is natural to assume that the motor system uses the similar mechanism to estimate the error size and correct the movement according to the estimation size. However, the three different optimal integration models considered in this study (Eqs. 6–8; Fig. 6a–c) could not reproduce the observed aftereffects. The failure of optimal integration theory to explain the aftereffect pattern might indicate the possible difference in the neuronal processes between the perception of the limb position and the error estimation, as represented by the fact that the motor adaptation is not necessarily associated with the perception of error (Kagerer et al., 1997; Hirashima and Nozaki, 2012; Hayashi et al., 2016).

Another concept proposed by Marko et al. (2012) states that the aftereffect is a linear summation of the aftereffects induced individually by visual or proprioceptive perturbation (Eq. 9). However, this model was inconsistent with the experimental results (Fig. 6d), as clearly demonstrated by the presence of a significant interaction in the aftereffects between the visual and proprioceptive perturbations (Fig. 4f). Furthermore, the amplitude of modulation of aftereffects with a change in the visual error size was constant in this model (Fig. 6d), which was also inconsistent with the experimental data (Fig. 4g). This contradiction between the present study and their study was probably caused by the fact that our experiment imposed a wider range of visual and proprioceptive errors; in the earlier study, the error size was <15° (estimated from their data) and the combinations of opposite perturbation directions were not tested.

The aftereffect pattern is explained by a divisive normalization mechanism

Divisive normalization is proposed as a canonical neural computation mechanism in the brain (Carandini and Heeger, 2011). We found that the divisive normalization model could reasonably reproduce the complicated dependence of the aftereffect on visual and proprioceptive perturbations. Ohshiro et al. (2011, 2017) demonstrated that the divisive normalization mechanism can account for the response of multisensory neurons encoding vestibular and visual signals. The neural response to both modality signals is smaller than the summation of the activity in response to sensory signals presented individually (crossmodal suppression), which is considered to be the signature of the divisive normalization mechanism. In our experiment, the aftereffect demonstrated a cross-modal suppression-like phenomenon; the aftereffect of combinations of visual and proprioceptive perturbations was smaller than the summation of the aftereffects of each perturbation (e.g., |f(30, 30)| < |f(30, 0)| + |f(0, 30)|; Fig. 4f).

We believe that this is the first behavioral demonstration of the divisive normalization mechanism accounting for the motor adaptation to visual and proprioceptive errors. This mechanism can explain not only why the aftereffects saturate with error size, but also the complicated dependence on visual and proprioceptive errors (Figs. 4f, 5a). However, there are several remaining issues that need to be investigated. First, the link between the response at the behavior level and the response at the neuronal circuit level remains unknown. A recent study (Shi et al., 2013) reported that the divisive normalization mechanism accounts for the neuronal response in the superior parietal lobule, which receives visual and proprioceptive signals, while monkeys performed reaching movement. Although the posterior parietal area is known to be involved in visuomotor control and learning (Tanaka et al., 2009; Mutha et al., 2011; Bédard and Sanes, 2014; Haar et al., 2015), it is still difficult to comprehend how this knowledge can be unified with our finding.

Second, although functional significance has been proposed from the perspective of efficient coding of sensory information (Beck et al., 2011; Carandini and Heeger, 2011), the functional role in the motor adaptation system is unclear. Shadmehr et al. demonstrated that adaptation to a force field in people with autism predominantly relied on proprioception (Haswell et al., 2009; Izawa et al., 2012). They also illustrated that aftereffects to combinations of visual and proprioceptive errors showed complicated modulation between healthy people and those with autism, although aftereffects specific to visual or proprioceptive perturbation were likely to be parallelly shifted (Marko et al., 2015), implying the possibility that the multisensory integration pattern by divisive normalization is peculiar in people with autism. Indeed, a recent study proposed that disorders in people with autism are related to the alteration of the divisive normalization pattern derived from imbalance between excitation and inhibition in neuronal circuits (Rosenberg et al., 2015). Studies investigating the peculiar characteristics of motor adaptation in patients with autism or neurological disorders might be beneficial to our understanding of the functional significance of divisive normalization in motor adaptation and the neuronal architecture implementing divisive normalization.

Third, our model does not consider the uncertainty in sensory error information. For example, previous studies have shown that the greater the uncertainty in visual feedback, the slower the motor adaptation (Burge et al., 2008; Wei and Körding, 2010). However, our model cannot deal with this type of problem because it does not include a term representing uncertainty (e.g., variance). Neural network models in which neurons or elements code for sensory error information according to their own tuning function are necessary to take the influence of uncertainty feedback into consideration.

Influence of online and endpoint feedback

According to the feedback error learning hypothesis (Kawato et al., 1987), the feedback motor command is used as a teaching signal to modify the motor command in the subsequent trial (Albert and Shadmehr, 2016). Thus, it is possible that the divisive normalization pattern in the aftereffect reflects the feedback response pattern. However, the patterns were considerably different between the aftereffect (Fig. 4f) and the feedback response (Fig. 7f). Furthermore, the aftereffect in the endpoint feedback condition exhibited the divisive normalization pattern (Fig. 7l). Therefore, the divisive normalization pattern in the aftereffect cannot be ascribed either to the feedback response or to the endpoint error processing.

Notably, the considerably different patterns between Figures 4f and 7l implied that the neuronal processing of online and endpoint errors for motor adaptation are somehow dissociated (Saijo and Gomi, 2010; Izawa and Shadmehr, 2011). The sensitivity of the aftereffect to visual error was considerably suppressed in the endpoint error feedback condition (compare Figs. 4f, 7l), indicating that the influence of the online proprioceptive error was dominant in the endpoint feedback condition and that the contribution of online visual feedback was greater than that of endpoint visual feedback in the production of the divisive normalization pattern. Further studies are necessary to clarify how these two types of feedback are cooperatively involved in creating the divisive normalization pattern in the aftereffect.

Modality-specific motor memory

Previous studies have investigated whether adaptation of visual rotation (kinematic) and of a novel force field (dynamic) is dependently (Krakauer et al., 1999) or independently accomplished (Tong et al., 2002). The results of Experiment 3 are relevant to this problem because the findings illustrated that motor memories for vision and proprioception are created independently and integrated at the output stages (Fig. 2b). The notion of separate motor memories for vision and proprioception was previously proposed (Judkins and Scheidt, 2014), but their conclusion that visual motor memory was dominant in motor adaptation is not consistent with our finding that proprioceptive error had a substantial influence on the aftereffect of visual error. This contradiction might result from their assumption that motor memories are updated by the linear summation of both modality errors, which differed from our scheme that indicated nonlinear integration.

The emergence of the aftereffect during the washout phase likely indicated that the memory for proprioception has a slower time constant than does the memory for vision (Fig. 8). This might be consistent with the previous observation that, even after adaptation to visual rotation, the elimination of visual feedback led the hand to move to the preadapted direction (Saijo and Gomi, 2012), implying that the adaptation of proprioception is slower. It has been recognized that adaptation to a novel dynamical environment is accomplished by slow and fast adaptation processes (Smith et al., 2006). Our results indicate a possibility that slow and fast processes are related to proprioception and vision, respectively.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the motor adaptation system integrates visual and proprioceptive error information by a divisive normalization mechanism. Furthermore, we found evidence that the motor memory for each sensory modality was formed separately and that the outputs from these memories were integrated. These results provide a novel view of the utilization of different sensory modality signals in motor control and adaptation.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a Grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Research Fellowships for Young Scientists to T.H. (17J02601) and by a KAKENHI (17H00874) to D.N. We thank Ken Takiyama and members of the Nozaki laboratory for their helpful comments and suggestions, and Asako Munakata for coordinating experiments.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Albert ST, Shadmehr R (2016) The neural feedback response to error as a teaching signal for the motor learning system. J Neurosci 36:4832–4845. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0159-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JM, Latham PE, Pouget A (2011) Marginalization in neural circuits with divisive normalization. J Neurosci 31:15310–15319. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1706-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bédard P, Sanes JN (2014) Brain representations for acquiring and recalling visual-motor adaptations. Neuroimage 101:225–235. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier PM, Chua R, Bard C, Franks IM (2006) Updating of an internal model without proprioception: a deafferentation study. Neuroreport 17:1421–1425. 10.1097/01.wnr.0000233096.13032.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge J, Ernst MO, Banks MS (2008) The statistical determinants of adaptation rate in human reaching. J Vis 8(4):20 1–19. 10.1167/8.4.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carandini M, Heeger DJ (2011) Normalization as a canonical neural computation. Nat Rev Neurosci 13:51–62. 10.1038/nrn3136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crevecoeur F, Munoz DP, Scott SH (2016) Dynamic multisensory integration: somatosensory speed trumps visual accuracy during feedback control. J Neurosci 36:8598–8611. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0184-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiZio P, Lackner JR (2000) Congenitally blind individuals rapidly adapt to coriolis force perturbations of their reaching movements. J Neurophysiol 84:2175–2180. 10.1152/jn.2000.84.4.2175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst MO. (2007) Learning to integrate arbitrary signals from vision and touch. J Vis 7(5):7 1–14. 10.1167/7.5.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst MO, Banks MS (2002) Humans integrate visual and haptic information in a statistically optimal fashion. Nature 415:429–433. 10.1038/415429a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin DW, So U, Burdet E, Kawato M (2007) Visual feedback is not necessary for the learning of novel dynamics. PLoS One 2:e1336. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goris RL, Movshon JA, Simoncelli EP (2014) Partitioning neuronal variability. Nat Neurosci 17:858–865. 10.1038/nn.3711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haar S, Donchin O, Dinstein I (2015) Dissociating visual and motor directional selectivity using visuomotor adaptation. J Neurosci 35:6813–6821. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0182-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haswell CC, Izawa J, Dowell LR, Mostofsky SH, Shadmehr R (2009) Representation of internal models of action in the autistic brain. Nat Neurosci 12:970–972. 10.1038/nn.2356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Yokoi A, Hirashima M, Nozaki D (2016) Visuomotor map determines how visually guided reaching movements are corrected within and across trials. eNeuro 3:ENEURO.0032–16.2016. 10.1523/ENEURO.0032-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirashima M, Nozaki D (2012) Distinct motor plans form and retrieve distinct motor memories for physically identical movements. Curr Biol 22:432–436. 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa J, Shadmehr R (2011) Learning from sensory and reward prediction errors during motor adaptation. PLoS Comput Biol 7:e1002012. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa J, Pekny SE, Marko MK, Haswell CC, Shadmehr R, Mostofsky SH (2012) Motor learning relies on integrated sensory inputs in ADHD, but over-selectively on proprioception in autism spectrum conditions. Autism Res 5:124–136. 10.1002/aur.1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KE, Hamilton AF, Wolpert DM (2002) Sources of signal-dependent noise during isometric force production. J Neurophysiol 88:1533–1544. 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judkins T, Scheidt RA (2014) Visuo-proprioceptive interactions during adaptation of the human reach. J Neurophysiol 111:868–887. 10.1152/jn.00314.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagerer FA, Contreras-Vidal JL, Stelmach GE (1997) Adaptation to gradual as compared with sudden visuo-motor distortions. Exp Brain Res 115:557–561. 10.1007/PL00005727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuga S, Hirashima M, Nozaki D (2013) Simultaneous processing of information on multiple errors in visuomotor learning. PLoS One 8:e72741. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawato M, Furukawa K, Suzuki R (1987) A hierarchical neural-network model for control and learning of voluntary movement. Biol Cybern 57:169–185. 10.1007/BF00364149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körding KP, Wolpert DM (2004) The loss function of sensorimotor learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:9839–9842. 10.1073/pnas.0308394101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körding KP, Beierholm U, Ma WJ, Quartz S, Tenenbaum JB, Shams L (2007) Causal inference in multisensory perception. PLoS One 2:e943. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer JW, Ghilardi MF, Ghez C (1999) Independent learning of internal models for kinematic and dynamic control of reaching. Nat Neurosci 2:1026–1031. 10.1038/14826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer JW, Pine ZM, Ghilardi MF, Ghez C (2000) Learning of visuomotor transformations for vectorial planning of reaching trajectories. J Neurosci 20:8916–8924. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08916.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner JR, DiZio P (1994) Rapid adaptation to coriolis force perturbations of arm trajectory. J Neurophysiol 72:299–313. 10.1152/jn.1994.72.1.299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marko MK, Haith AM, Harran MD, Shadmehr R (2012) Sensitivity to prediction error in reach adaptation. J Neurophysiol 108:1752–1763. 10.1152/jn.00177.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marko MK, Crocetti D, Hulst T, Donchin O, Shadmehr R, Mostofsky SH (2015) Behavioural and neural basis of anomalous motor learning in children with autism. Brain 138:784–797. 10.1093/brain/awu394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni P, Krakauer JW (2006) An implicit plan overrides an explicit strategy during visuomotor adaptation. J Neurosci 26:3642–3645. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5317-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutha PK, Sainburg RL, Haaland KY (2011) Critical neural substrates for correcting unexpected trajectory errors and learning from them. Brain 134:3647–3661. 10.1093/brain/awr275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshiro T, Angelaki DE, DeAngelis GC (2011) A normalization model of multisensory integration. Nat Neurosci 14:775–782. 10.1038/nn.2815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshiro T, Angelaki DE, DeAngelis GC (2017) A neural signature of divisive normalization at the level of multisensory integration in primate cortex. Neuron 95:399–411.e8. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipereit K, Bock O, Vercher JL (2006) The contribution of proprioceptive feedback to sensorimotor adaptation. Exp Brain Res 174:45–52. 10.1007/s00221-006-0417-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren M, Liao R, Urtasun R, Sinz FH, Zemel RS (2016) Normalizing the normalizers: comparing and extending network normalization schemes. arXiv:1611.04520. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg A, Patterson JS, Angelaki DE (2015) A computational perspective on autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:9158–9165. 10.1073/pnas.1510583112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijo N, Gomi H (2010) Multiple motor learning strategies in visuomotor rotation. PLoS One 5:e9399. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijo N, Gomi H (2012) Effect of visuomotor-map uncertainty on visuomotor adaptation. J Neurophysiol 107:1576–1585. 10.1152/jn.00204.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidt RA, Reinkensmeyer DJ, Conditt MA, Rymer WZ, Mussa-Ivaldi FA (2000) Persistence of motor adaptation during constrained, multi-joint, arm movements. J Neurophysiol 84:853–862. 10.1152/jn.2000.84.2.853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SH. (2016) A functional taxonomy of bottom-up sensory feedback processing for motor actions. Trends Neurosci 39:512–526. 10.1016/j.tins.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seilheimer RL, Rosenberg A, Angelaki DE (2014) Models and processes of multisensory cue combination. Curr Opin Neurobiol 25:38–46. 10.1016/j.conb.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadmehr R, Mussa-Ivaldi FA (1994) Adaptive representation of dynamics during learning of a motor task. J Neurosci 14:3208–3224. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03208.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadmehr R, Smith MA, Krakauer JW (2010) Error correction, sensory prediction, and adaptation in motor control. Annu Rev Neurosci 33:89–108. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Apker G, Buneo CA (2013) Multimodal representation of limb endpoint position in the posterior parietal cortex. J Neurophysiol 109:2097–2107. 10.1152/jn.00223.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Ghazizadeh A, Shadmehr R (2006) Interacting adaptive processes with different timescales underlie short-term motor learning. PLoS Biol 4:e179. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Sejnowski TJ, Krakauer JW (2009) Adaptation to visuomotor rotation through interaction between posterior parietal and motor cortical areas. J Neurophysiol 102:2921–2932. 10.1152/jn.90834.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong C, Wolpert DM, Flanagan JR (2002) Kinematics and dynamics are not represented independently in motor working memory: evidence from an interference study. J Neurosci 22:1108–1113. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-01108.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beers RJ, Sittig AC, van der Gon JJ (1999) Integration of proprioceptive and visual position-information: an experimentally supported model. J Neurophysiol 81:1355–1364. 10.1152/jn.1999.81.3.1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beers RJ, Wolpert DM, Haggard P (2002) When feeling is more important than seeing in sensorimotor adaptation. Curr Biol 12:834–837. 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00836-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb R, Glimcher PW, Louie K (2014) Rationalizing context-dependent preferences: divisive normalization and neurobiological constraints on choice. SSRN Electronic Journal 2462895. [Google Scholar]

- Wei K, Körding K (2009) Relevance of error: what drives motor adaptation? J Neurophysiol 101:655–664. 10.1152/jn.90545.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei K, Körding K (2010) Uncertainty of feedback and state estimation determines the speed of motor adaptation. Front Comput Neurosci 4:11. 10.3389/fncom.2010.00011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostwoud Wijdenes L, Medendorp WP (2017) State estimation for early feedback responses in reaching: intramodal or multimodal? Front Integr Neurosci 11:38. 10.3389/fnint.2017.00038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert DM, Ghahramani Z, Jordan MI (1995) An internal model for sensorimotor integration. Science 269:1880–1882. 10.1126/science.7569931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousif N, Cole J, Rothwell J, Diedrichsen J (2015) Proprioception in motor learning: lessons from a deafferented subject. Exp Brain Res 233:2449–2459. 10.1007/s00221-015-4315-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Simulation result of the modality-specific motor memory model. The results of Experiment 3 indicate that vision and proprioception are likely to have distinct motor memories. One possible model is that each motor memory (xv and xp are motor memories for vision and proprioception, respectively) is updated by the divisively normalized error and the outputs are integrated as follows:

|

When the single trial adaptation is measured (xv(i) = xp(i) = 0), the aftereffect should be

|

which is equivalent to Eq. 1 in the main text. This model was used to simulate the trial dependent pattern of aftereffect in Experiment 3 (a). The parameters used for this simulation can reproduce the single trial aftereffects in Experiment 1 (b). Download Figure 8-1, EPS file (224.4KB, eps)