Summary

One of the remaining challenges to describing an individual's genetic variation lies in the highly heterogeneous and complex genomic regions that impede the use of classical reference-guided mapping and assembly approaches. Once such region is the Immunoglobulin heavy chain locus (IGH), which is critical for the development of antibodies and the adaptive immune system. We describe ImmunoTyper, the first PacBio-based genotyping and copy number calling tool specifically designed for IGH V genes (IGHV). We demonstrate that ImmunoTyper's multi-stage clustering and combinatorial optimization approach represents the most comprehensive IGHV genotyping approach published to date, through validation using gold-standard IGH reference sequence. This preliminary work establishes the feasibility of fine-grained genotype and copy number analysis using error-prone long reads in complex multi-gene loci and opens the door for in-depth investigation into IGHV heterogeneity using accessible and increasingly common whole-genome sequence.

Subject Areas: Biological Sciences, Bioinformatics, Computational Bioinformatics, Genomic Analysis

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

We describe ImmunoTyper, a WGS Immunoglobulin Heavy Chain Variable Genotyping tool

-

•

Immunotyper is the first such tool to use long reads and call alleles for pseudogenes

-

•

We demonstrate high allele call accuracy using simulated and real WGS data

Biological Sciences; Bioinformatics; Computational Bioinformatics; Genomic Analysis

Introduction

With the advent of modern, high-speed bioinformatics tools and high-throughput sequencing, reconstructing a human genome has gone from being one of the big challenges in genomics to standard protocol. Despite being a routine step in modern bioinformatics pipelines, there remains parts of the genome that are difficult to reconstruct using standard techniques. One such region is the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus (IGH), whose genes encode the foundation to the structure and development of antibodies. Although IGH genes are critical to the structure and function of the adaptive immune system of vertebrates, performing genotyping and copy number analysis of IGH genes remains challenging owing to the complexity of the region, which is one of the most dynamic regions of the human genome (Watson and Breden, 2012).

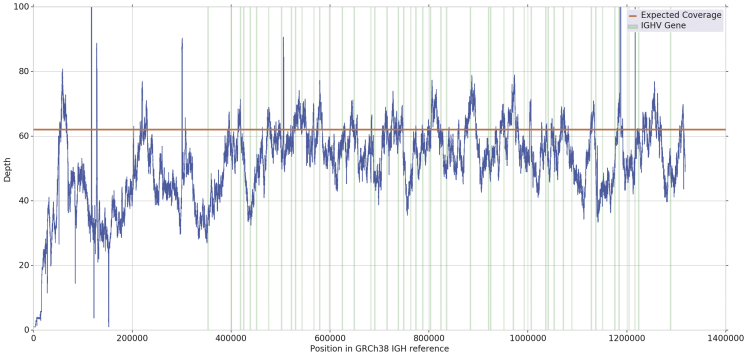

Of the four classes of coding gene segments present in the IGH region, the Variable genes class (IGHV) plays a critical role in defining epitope binding affinity, as it completely contains two and partially contains the last of the three complementary-determining regions. However, many of the IGHV alleles are highly similar (see Figure 1), which in combination with their short length of between 165 and 305 bp (mean of 291 bp) and the high number in an individual (can be greater than 50 functional genes [Watson et al., 2013, Matsuda et al., 1998]), makes the problem of IGHV genotyping challenging. To further complicate the problem, the IGH region has been shown to contain many large structural variants (SVs), including segmental duplications, large insertions and deletions, and other copy number variants (CNVs) (Watson et al., 2013). Finally, there are two non-functional orphons of IGH (on chromosomes 15 and 16) that have similar sequence to IGH (Lefranc, 2001a). As a result, classical reference-based mapping approaches to IGH analysis typically perform poorly (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Histogram of the Edit Distance between Each Allele from the IGHV (Pseudo)Gene Database and its Most Similar Allele (with Respect to Edit Distance)

Figure 2.

Read Depth of IGH Region for CHM1 WGS PacBio Reads Mapped to CHM1 Reference Using minimap2 with Default Parameters, Demonstrating Significant Deviation from the Expected Coverage, Including at Positions Containing IGHV Genes, Which Are Marked by Vertical Green Lines

To date there have been two attempts at IGHV genotyping using high-throughput sequence from germline DNA-sourced materials, both focused exclusively on functional genes. For clarity, we consider a successful IGHV genotyping result to report all the IGHV genes present in a given sample and report the allele for every copy of every IGHV gene. Work by Yu et al. (2017) created a whole-genome sequencing (WGS) Illumina short read analysis pipeline for identification of IGHV and T cell receptor sequence using a reference mapping-based variant calling and frequency thresholding. Although the results of their paper are initially impressive, with 8,750 novel IGHV sequences having been found, there have been doubts raised regarding the accuracy of the findings by others in the field (Watson et al., 2017, Boyd et al., 2010, Kidd et al., 2012, Gidoni et al., 2019). One of the main criticisms is the reliance on a genome reference. The high degree of haplotype diversity mentioned above means that any reads that may originate from an insertion or novel sequence in the IGH region, relative to the mapping reference, will be missed from the pipeline.

The other work on IGHV genotyping using germline sequence data has been done by Luo et al., 2016, Luo et al., 2019, also using WGS Illumina short read data. Although their initial work also relied on whole reference genome mapping, without addressing possible novel insertion sequence, their later work avoided this pitfall by mapping short reads directly to IGHV reference sequences. This method focuses on gene identification and copy number calling. However, their method calls alleles only for 11 functional genes, as they identify these as only having a single copy per chromosome. Additionally, there are seven groups of genes, each of which is a set of genes they are not able to differentiate owing to high sequence similarity.

One increasingly popular approach to investigating the variations within the genes of the IGH region is through genotype and haplotype inference, using repertoire sequencing data. Although the analysis of germline sequencing data is challenging, gathering sequencing data on expressed IGH sequences, typically called Adaptive Immune Receptor Repertoire sequencing (AIRR-seq), is commonplace, has established protocols, and can easily be sequenced to a high depth (Vander Heiden et al., 2018). The availability and quality of these data make it an appealing source to infer and investigate the germline sequence; however, owing to the nature of IGH sequence expression this is not straightforward. An IGH mRNA sequence, as expressed by a B cell, is not only different from the germline sequence owing to VDJ recombination, but has potentially also undergone somatic hypermutation, which introduces new variants relative to the germline sequence. However, despite these challenges, there have been numerous published studies and tools that have investigated the IGHV germline sequence through repertoire sequencing inference and have been successful at identifying novel IGHV alleles and features (Gadala-Maria et al., 2015, Gadala-Maria et al., 2019, Boyd et al., 2010, Corcoran et al., 2016, Ralph and Matsen, 2016, Thörnqvist and Ohlin, 2018). There has additionally been work done on haplotype inference through statistical learning frameworks, using the IGHJ genotype (Kirik et al., 2017, Kidd et al., 2012) and/or IGHD genotype (Gidoni et al., 2019) as an IGHV haplotype indicator.

However, it has been noted that there are challenges to performing IGHV germline analysis through repertoire inference. For example, recent work has demonstrated that inferring some IGHV variants can be nearly impossible because of the unpredictable removal of 3′ bases during VDJ recombination or be particularly hard to overcome at regions of “mutational hotspots” (Kirik et al., 2017). Additionally, it has been shown that the initial reference database used can affect the reliability of inference calls for alleles that are highly similar (Kirik et al., 2017).

Another inherent challenge to IGHV inference is the effect of non-uniform expression of certain VDJ configurations. This effect can be additionally complicated by the types and ratios of B cells that are sequenced. Fundamentally, since inferring the presence of some allele is dependent on the allele being expressed, the lack of some allele does not indicate its absence in the germline sequence. This means that, although inference may result in the identification of confident true positives, true negatives are impossible to differentiate from false negatives. Additionally, since the repertoire is adaptive and dynamic, some method to account for possible temporal biases to expression ratios is necessary to confidently make claims regarding the general functional significance of the presence or absence of any given allele. The effect of expression bias is also particularly relevant to haplotype inference, whose reliance on gene usage estimates can be directly confounded by expression bias (Gidoni et al., 2019).

Although inference techniques have made significant progress at genotyping despite the challenges, there has been little work done on the other major sources of IGH heterogeneity, namely, SVs and CNVs. These variants are expected to be common, as work by Watson et al. (2013) has discovered several large-scale insertions and deletions in the IGH region, each containing multiple IGHV genes. However, this work was done using Sanger sequencing of BAC and fosmid clones, which is prohibitively expensive and time consuming. Haplotype inference has had some success at CNV calling, deletion detection, and even phased haplotype calling (Gidoni et al., 2019, Kidd et al., 2012); however, it is limited by gene expression bias as noted above. The work by Luo et al. includes copy number calls but does not call alleles for genes with CNVs, thus missing a critical step in the path toward complete haplotype calling.

Another large gap in our knowledge about IGH heterogeneity are non-coding sequence variants. Non-coding sequence is already known to play a critical role in the antibody repertoire as it contains the recombination signal sequence, which is required for V(D)J recombination (Janeway et al., 2001). However, limitations in methodology have inhibited investigation into possible further effects through mechanisms such as enhancers and promoters.

Identification of novel IGH and IGHV sequences, genes, and alleles is an important problem, as it has been noted that the primary database for IGH gene reference sequences, hosted by the international ImMunoGeneTics information system (IMGT) (Lefranc et al., 2015), is incomplete (Ohlin et al., 2019), and the complexity of the IGH locus is likely to lead to high sequence heterogeneity across individuals and populations. However, there is still a need for fast IGHV genotyping of known alleles using common data types that are not specific to IGH research. Such tools can be integrated into standard precision medicine pipelines, allowing for investigations such as disease association studies to be done with larger sample sizes. Although the performance of IGHV genotyping tools may suffer initially depending on their degree of reliance on established IGHV reference databases, they will increase in accuracy as databases become more complete over time.

In this paper we present ImmunoTyper, an IGHV genotyping and CNV calling tool that is the first to be based on long read data. By using long read data we ensure that reads span the complete IGHV coding region, and they provide information from non-coding regions, at the cost of increased sequencing error rate over short read technologies. In order to avoid the gene expression biases found in inference-based methods, it utilizes WGS to provide a complete picture of the IGHV germline landscape. Although ImmunoTyper in its current implementation is solely for rapid genotyping of known IGHV alleles, several of its design features, such as allele identification using ambiguity instead of identity, can allow for implementation of novel allele discovery in future versions of the tool. Finally, ImmunoTyper is the first IGH-specific tool to report non-coding sequence by providing high-quality sequence for regions flanking IGHV genes, as well as the first to provide allele and CNV calling for the vast majority of IGHV pseudogenes.

Results

Owing to the lack of published IGH germline sequences, our ability to validate allele calls and copy number variants is limited. As a result, we performed experiments using simulated data using both the GRCh37 and GRCh38 references, which are the only published complete IGH sequences. Since the GRCh38 IGH reference is derived from the CHM1 hydatidiform mole haploid genome (Watson et al., 2013), we were also able to perform tests with real data using publicly available WGS data for CHM1. For clarity, we used CHM1 instead of GRCh38 to reference this sample.

Simulated Data

Simulated data experiments were set up with the goal of testing the ImmunoTyper method, without the confounding effects of unavoidable noise inherent in WGS datasets.

For generating the simulated data, we first extracted the IGHV genes and pseudogenes, along with 1-kbp flanking regions, from the GRCh37 (NCBI NC_000014.8:106031614-107289051) and CHM1 (NCBI NC_000014.9:105586437-106880844) references using the NCBI GenBank annotations (Clark et al., 2015). Next, we discarded all sequences corresponding to alleles that are ignored (as described in Transparent Methods). We simulated the reads from the IGHV-containing sequences at 20x using Simlord (Stöcker et al., 2016) in single-pass configuration, resulting in a 15.8% mean total error rate. This resulted in 2,360 reads for the CHM1 sample and 2,236 for the GRCh37 sample. The reads are simulated so that their length matches the length of the extracted sequences (2,300 bp) to emulated extracted subreads from a WGS sample. The resulting sets of reads were then combined and provided as input to ImmunoTyper. The option “--no-coverage-estimation” was used to skip the subread coverage estimation step described in Transparent Methods, and use the user provided depth parameter of 20x. For the CHM1 and GRCh37 samples, 1,524 and 1,323 of the inputs reads, respectively, were identified as ambiguous and assigned in the second stage of the pipeline.

In addition to these simulated haploid runs, the subreads from both samples were combined to create a set of 4,596 reads that simulate a diploid sample. Of the input reads, 2,760 were identified as ambiguous.

Results are shown in Table 1, where ImmunoTyper demonstrates strong results in all simulated samples, with precision and recall above 94%, with the exception of 89% recall in the simulated CHM1 sample. Note that the results in Table 1 are for all functional IGHV genes and non-functional IGHV pseudogenes. Additionally, in all cases except GRCh37 ImmunoTyper was able to successfully differentiate alleles that were distinguished by only a single SNP (see section Investigation into False-Positive Allele Calls and Figures S5–S7). Note that True Pos indicates the allele was called by ImmunoTyper and was present in the sample, False Pos indicates the allele was called by ImmunoTyper but was not in the sample, and False Neg indicates the allele was not called by ImmunoTyper but was present in the sample.

Table 1.

Genotype Results for Simulated and CHM1 Real Data Samples

| Sample | # IGHV Occurrences in Reference | # IGHV Calls | Precision | Recall | True Positive | False Positive | False Negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHM1 (simulated) | 117 | 111 | 94.6% | 89.7% | 105 | 6 | 12 |

| GRCh37 (simulated) | 112 | 109 | 97.2% | 94.6% | 106 | 3 | 6 |

| CHM1 + GRCh37 (simulated) | 229 | 227 | 94.3% | 93.4% | 214 | 13 | 15 |

| CHM1 WGS | 117 | 110 | 87.3% | 82.1% | 96 | 14 | 21 |

WGS Data with Validation

ImmunoTyper was tested on the publicly available CHM1 PacBio sequence (62x coverage; SRA: SRX1164774) (Chaisson et al., 2015), and the resulting allele calls were validated as with the simulated CHM1 data. A total of 7,772 reads were extracted from the WGS sample, 3,131 of which contained at least one complete IGHV gene with flanking sequences, resulting in 5,176 subreads; 1,431 were identified as ambiguous. Table 1 shows that ImmunoTyper successfully genotypes the WGS CHM1 sample with reasonable precision and recall values of 87% and 82%, respectively, and is able to successfully differentiate alleles that have as few as four distinguishing SNPs (see section Investigation into False-Positive Allele Calls and Figure S8).

Sequence Recovery and Reference Mapping

To further evaluate the performance of ImmunoTyper in subread error reduction, consensus sequences (including coding and non-coding flanking sequences) from all clusters were mapped back to their reference sequence using minimap2 (Li, 2018) with default parameters. As shown in Table 2, ImmunoTyper reduces the median sequence error rate by at least 86% from the raw read error rate. Visualizations of the distribution of error reduction can be found in Figures S1–S4. Note that the expected error rate for PacBio reads is taken from Laehnemann et al., (2015).

Table 2.

Allele Sequence Error Reduction Results

| Sample | Expected Read Error | Median Mapping Error |

|---|---|---|

| CHM1 (simulated) | 15.8% | 2.0% |

| GRCh37 (simulated) | 15.8% | 2.0% |

| CHM1 + GRCh37 (simulated) | 15.8% | 2.2% |

| CHM1 WGS | 16.19%a | 2.3% |

Taken from Laehnemann et al., 2015.

Investigation into False-Positive Allele Calls

In order to investigate whether sequence similarity is a major contributor to false-positive allele calls, for each sample we plot the number of false-positive alleles against the number of SNPs that distinguish them from their most similar allele in the sample. We also include true positives in the plot to provide context for the minimum number of variants ImmmunoTyper needs to successfully differentiate and call alleles. The plots can be found in Figures S5–S8.

Identification of Sequence Differences between GRCh37 and CHM1 References

The GRCh37 and CHM1 references have significant difference in sequence and IGHV gene composition. The two references together contain four of the six known IGH insertion sequences listed in IMGT and partially cover a fifth (Lefranc et al., 2015, Clark et al., 2015, Lefranc, 2001b, Lefranc, 2001a). In Table 3, we provide the IGHV genes and pseudogenes contained in each insertion sequence, as well as list the source reference and an individual identifier.

Table 3.

Sequence Differences between CHM1 and GRCh37 References

| Insertion Identifier | Reference | Genes and Pseudogenes Present and Their Alleles |

|---|---|---|

| A | CHM1 | 1-69*06, 1-69-2*01, 2-70D*04, 3-69-1*01 |

| B | GRCh37 | 4-31*02, (II)-31-1*01 |

| C | CHM1 | (II)-30-21*01, 4-30-2*01 |

| D | CHM1 | 3-64D*06, 5-10-1*03 |

| E | GRCh37 | 3-9*01, 2–10*01, 1–8*01 |

| F | CHM1 | 7-4-1*01 |

The simulated diploid sample is the most suited to evaluate ImmunoTyper's ability to identify inserted sequence as it covers the most amount of insertions. Table 4 provides a summary of the gene and allele calls for IGHV genes and pseudogenes belonging to inserted sequence. ImmunoTyper was able to call the presence and correctly identify the alleles 12 of 14 genes and pseudogenes contained in the inserted sequences, demonstrating the ability to identify known insertion sequences in a sample. The missing allele calls were likely lost owing to high coding and flanking sequence similarity with other genes in the region (89% and 88% sequence identity for 3-69-*01 and 3-71*01; 1-8*01 and 1-69*06, respectively).

Table 4.

IGHV Identification in Insertion Sequences Between GRCh37 and CHM1 in Diploid Sample

| Insertion | Reference | Number of Genes and Pseudogenes | Number of Matching Genes in Result | Number of Correct Allele Calls | Missing Allele Calls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | CHM1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3-69-1*01 |

| B | GRCh37 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| C | CHM1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| D | CHM1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| E | GRCh37 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1-8*01 |

| F | CHM1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

CNV Analysis

There are several IGHV genes in the GRCh37 and CHM1 references that are present with multiple copies. The greatest number of CNVs are present in the GRCh37 + CHM1 diploid sample, and ImmunoTyper's results for calling all CNV genes in the sample are summarized in Table 5. ImmunoTyper accurately calls the copies and alleles for the CNV genes in the sample in all cases except for 1-69, where the incorrect calls are likely a result of the extreme challenge of differentiating the *01 and *06 alleles as they differ by a single base pair. The 4-31 gene is included despite having a copy number of 2, because the second copy (4-30-2) is due to a duplication in the B insertion sequence in GRCh37, rather than diploidy.

Table 5.

Calls for Known CNV Genes in the CHM1 + GRCh37 Sample

| Gene | Number of Copies in Sample | Number of Copies Copies Called |

Correct Allele Calls | False-Positive Calls | False-Negative Calls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-69 | 4 | 5 | 1-69-2*01, 1-69*06, 1-69*06 | 1-69*06, 1-69*06 | 1-69*01 |

| 2-70 | 3 | 3 | 2-70*01, 2-70D*04 2-70*13 | ||

| 3-64 | 3 | 3 | 3-64*02, 3-64D*06 3-64*02 | ||

| 4-31 | 2 | 2 | 4-30-2*01, 4-31*02 |

Discussion

ImmunoTyper represents a generalizable approach to multigene genotyping and copy number analysis. The results described above, although limited in sample size, provide robust validation of the methodology against publicly available genotype calls that have been produced through gold-standard approaches.

In addition to accurate genotyping results with high precision and recall, the low mapping error rates described in section Sequence Recovery and Reference Mapping demonstrate the success of our clustering approach, especially considering the high error rates of the source reads and moderate sequencing depth. However, it is clear that complete IGHV genotyping using long reads is especially difficult. ImmunoTyper under-reported the number of IGHV genes present in the CHM1 WGS sample, likely because of variation in the sequencing depth or IGHV-containing subread dropout due to subreads not being identified as a result of high sequence error. Subread dropout and potential noise from mistakenly including subreads from elsewhere in the genome, such as the 2 IGH orphons, are also likely explanations of the difference seen in the results of the CHM1 WGS and CHM1 simulated samples, in addition to the unavoidable shortcomings of simulating sequencing data. There also remain a few outlying cases in all samples where the allele call was incorrect and/or the sequence recovery had a high number of errors. Given the proportion of IGHV alleles that have a high degree of sequence similarity, it may be exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to achieve perfect genotyping and CNV calls using error-prone long reads without reducing the sequence error rate through a method such as CCS reads or increasing the sequencing depth.

In addition to identifying known IGHV alleles, ImmunoTyper also provides an opportunity to discover novel sequences through the following features. First, the Mapping-based clustering step clusters reads based on ambiguity rather than on allele sequence similarity. This allows for reads originating from a novel allele to be clustered with the closest matching allele in the database. Super-clusters also account for novel alleles, as they are formed solely based on read-to-read sequence similarity and are therefore not dependent on the known allele database. Finally, the non_code_cov_var error function acts as a reference-free counterbalance to code_var_cov error function, as it is independent of allele references and influences clustering based on read-to-read similarity, under the constraints of variant depth. As a result, the user is able to call novel alleles using the output consensus sequence for each IGHV gene. However, owing to the challenge of calling novel alleles using long reads, especially if they differ significantly from known alleles, ImmunoTyper is focused on known allele calling.

In addition to IGH, there are other regions of the genome where ImmunoTyper could be applied with minimal modification. In particular, the immunoglobulin κ and λ light chain loci and the T cell receptor loci are related to IGH in that they all share a similar multi-gene segment construction and undergo V(D)J recombination (Janeway et al., 2001). Luo et al. (2019) have taken this approach by applying their tool to the T cell beta variable locus. Extending the protocol to these similar regions is an accessible opportunity to investigate lesser-studied regions of the genome, given the current configuration of ImmunoTyper.

Fundamentally, ImmunoTyper is the first IGHV genotyping tool to use error-prone long reads, the first to integrate pseudogene calls, and the first to provide data on non-coding sequence that flanks IGHV genes. Although it is developed specifically for IGHV analysis, the approach and the integer linear programming formulation for allele assignment is generalizable to any multi-gene genotyping and copy number analysis problem with known alleles.

Although this initial investigation was intentionally limited to samples that have published gold-standard references, the results make us confident that ImmunoTyper represents the closest attempt at complete IGHV genotyping using WGS data to date.

Limitations of the Study

By limiting our testing of ImmunoTyper to samples with published gold-standard references, we can be confident in the accuracy of our results; however, that comes at the cost of a certain degree of generalizability. We can speculate that there may exist IGH haplotypes that have combinations of IGHV alleles, either previously described or novel, which are challenging for ImmunoTyper to accurately identify. However, in the absence of further complete IGH haplotypes or alternative validation methods to compare ImmunoTyper with, we are limited in our ability to significantly test ImmunoTyper beyond what has been demonstrated in this paper.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Felix Breden and Pavel Pevzner for introducing us to the problem and offering us encouragement and help during the development and testing of ImmunoTyper. This research was partially funded by NSF Grant CCF-1619081, NIH grant GM108348, and the Indiana University Grand Challenges Program, Precision Health Initiative to SCS.

Author Contributions

M.F., S.C.S., and C.T.W. identified the problem and developed its mathematical formulation; M.F. and S.C.S. developed the theory underlying ImmunoTyper; M.F. implemented ImmunoTyper; M.F. and E.H. optimized and tested ImmunoTyper and evaluated it on various datasets; M.F. and S.C.S. wrote the manuscript with the help and feedback from E.H. and C.T.W.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: March 27, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.100883.

Data and Code Availability

The datasets used for obtaining the results of this article can be retrieved from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) via accession number SRA: SRX1164774. These datasets have been published in an article by Chaisson et al. (2015). The instructions to generate simulated data used in this article can be found in Simulated Data.

Supplemental Information

References

- Boyd S.D., Gaëta B.A., Jackson K.J., Fire A.Z., Marshall E.L., Merker J.D., Maniar J.M., Zhang L.N., Sahaf B., Jones C.D. Individual variation in the germline ig gene repertoire inferred from variable region gene rearrangements. J. Immunol. 2010;184:6986–6992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaisson M.J., Huddleston J., Dennis M.Y., Sudmant P.H., Malig M., Hormozdiari F., Antonacci F., Surti U., Sandstrom R., Boitano M. Resolving the complexity of the human genome using single-molecule sequencing. Nature. 2015;517:608. doi: 10.1038/nature13907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K., Karsch-Mizrachi I., Lipman D.J., Ostell J., Sayers E.W. Genbank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;44:D67–D72. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran M.M., Phad G.E., Bernat N.V., Stahl-Hennig C., Sumida N., Persson M.A., Martin M., Hedestam G.B.K. Production of individualized v gene databases reveals high levels of immunoglobulin genetic diversity. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13642. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadala-Maria D., Gidoni M., Marquez S., Vander Heiden J.A., Kos J.T., Watson C.T., OConnor K., Yaari G., Kleinstein S.H. Identification of subject-specific immunoglobulin alleles from expressed repertoire sequencing data. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:129. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadala-Maria D., Yaari G., Uduman M., Kleinstein S.H. Automated analysis of high-throughput b-cell sequencing data reveals a high frequency of novel immunoglobulin v gene segment alleles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2015;112:E862–E870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417683112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidoni M., Snir O., Peres A., Polak P., Lindeman I., Mikocziova I., Sarna V.K., Lundin K.E., Clouser C., Vigneault F. Mosaic deletion patterns of the human antibody heavy chain gene locus shown by bayesian haplotyping. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:628. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08489-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeway C.A., Travers P., Walport M., Shlomchik M. Fifth Edition. Garland Publishing; 2001. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd M.J., Chen Z., Wang Y., Jackson K.J., Zhang L., Boyd S.D., Fire A.Z., Tanaka M.M., Gaëta B.A., Collins A.M. The inference of phased haplotypes for the immunoglobulin h chain v region gene loci by analysis of VDJ gene rearrangements. J. Immunol. 2012;188:1333–1340. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik U., Greiff L., Levander F., Ohlin M. Parallel antibody germline gene and haplotype analyses support the validity of immunoglobulin germline gene inference and discovery. Mol. Immunol. 2017;87:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laehnemann D., Borkhardt A., McHardy A.C. Denoising DNA deep sequencing data high-throughput sequencing errors and their correction. Brief. Bioinform. 2015;17:154–179. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbv029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefranc . Academic Press; 2001. The Immunoglobulin Factsbook. [Google Scholar]

- Lefranc M.P. Nomenclature of the human immunoglobulin heavy (IGH) genes. Exp. Clin. Immunogenet. 2001;18:100–116. doi: 10.1159/000049189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefranc M.P., Giudicelli V., Duroux P., Jabado-Michaloud J., Folch G., Aouinti S., Carillon E., Duvergey H., Houles A., Paysan-Lafosse T. IMGT(R), the international ImMunoGeneTics information system(R) 25 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D413–D422. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:3094–3100. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S., Jane A.Y., Li H., Song Y.S. Worldwide genetic variation of the IGHV and TRBV immune receptor gene families in humans. Life Sci. Alliance. 2019;2:e201800221. doi: 10.26508/lsa.201800221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S., Jane A.Y., Song Y.S. Estimating copy number and allelic variation at the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus using short reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016;12:e1005117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda F., Ishii K., Bourvagnet P., Kuma K.i., Hayashida H., Miyata T., Honjo T. The complete nucleotide sequence of the human immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region locus. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:2151–2162. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlin M., Scheepers C., Corcoran M., Lees W.D., Jackson K.J.L., Ralph D., Schramm C.A., Marthandan N. Inferred allelic variants of immunoglobulin receptor genes: a system for their evaluation, documentation, and naming. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph D.K., Matsen F.A., IV Consistency of VDJ rearrangement and substitution parameters enables accurate B cell receptor sequence annotation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016;12:e1004409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöcker B.K., Köster J., Rahmann S. Simlord: simulation of long read data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:2704–2706. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thörnqvist L., Ohlin M. The functional 3’-end of immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) genes. Mol. Immunol. 2018;96:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Heiden J.A., Marquez S., Marthandan N., Bukhari S.A.C., Busse C.E., Corrie B., Hershberg U., Kleinstein S.H., Matsen F.A., IV AIRR community standardized representations for annotated immune repertoires. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2206. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson C., Breden F. The immunoglobulin heavy chain locus: genetic variation, missing data, and implications for human disease. Genes Immun. 2012;13:363. doi: 10.1038/gene.2012.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson C.T., Matsen F.A., Jackson K.J., Bashir A., Smith M.L., Glanville J., Breden F., Kleinstein S.H., Collins A.M., Busse C.E. Comment on a database of human immune receptor alleles recovered from population sequencing data. J. Immunol. 2017;198:3371–3373. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson C.T., Steinberg K.M., Huddleston J., Warren R.L., Malig M., Schein J., Willsey A.J., Joy J.B., Scott J.K., Graves T.A. Complete haplotype sequence of the human immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable, diversity, and joining genes and characterization of allelic and copy-number variation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;92:530–546. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Ceredig R., Seoighe C. A database of human immune receptor alleles recovered from population sequencing data. J. Immunol. 2017;198:2202–2210. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used for obtaining the results of this article can be retrieved from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) via accession number SRA: SRX1164774. These datasets have been published in an article by Chaisson et al. (2015). The instructions to generate simulated data used in this article can be found in Simulated Data.