Abstract

Background: Community health workers (CHWs) are a well-established source to improve patient health care, yet their training and support remain suboptimal. This limits program expansion and potentially compromises patient safety. The objective of the study was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of weekly training and support by telemedicine (videoconferencing).

Materials and Methods: CHWs (n = 6) who led diabetes group visits for low-income Latinos met weekly with a health care professional for training and support. Feasibility and acceptability outcome measures included telemedicine usability, knowledge of diabetes (baseline to 6 months), and program satisfaction.

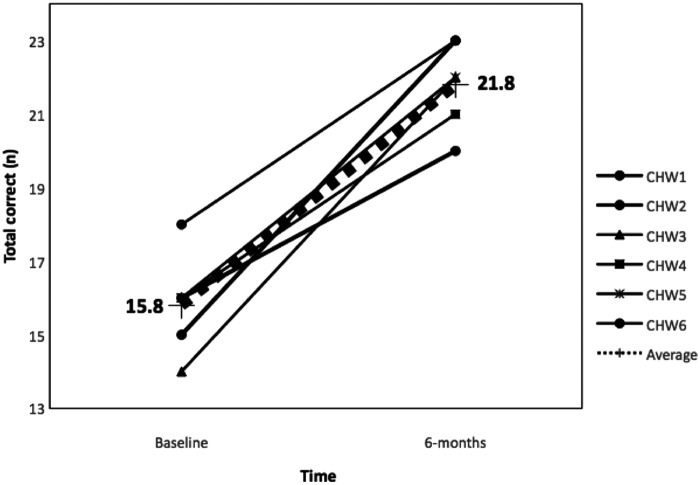

Results: Telemedicine training and support were found to be feasible and acceptable as measured by usability (Telehealth Usability Questionnaire: average 4.7/5.0, ±0.4), knowledge (Diabetes Knowledge Test: pretest 15.8 ± 1.3, posttest 21.8 ± 1.2, p < 0.001, respectively), and satisfaction (Texas Department of State Health Services survey: average 5.8/6.0, ±0.5). All CHWs preferred telemedicine to in-person training.

Conclusions: Telemedicine is a feasible and acceptable modality to train and support CHWs.

Keywords: community health worker, training, education, low income, telemedicine, diabetes

Introduction

Heightening health care disparities have resulted in shifting chronic disease management approaches to lessen patient and system burdens.1 Increased involvement of community health workers (CHWs) is a salient example. These individuals are local community members who serve as liaisons between the individual and the health care system.2 The interaction between CHWs and patients has been associated with significant improvements in patient health and access to care.2–5 CHW involvement in patient care has also been shown to be a cost-effective and culturally competent intervention in a range of ethnicities, diseases, and settings.2–5 This has resulted in many health care systems increasing CHW involvement in patient care as the shortage of primary care providers continues.5–7

Although the involvement of CHWs in patient care has been present for decades, their training and support have remained suboptimal.7,8 This may explain why not all CHW programs have been successful. CHW training is insufficient without an emphasis on support.9–11 Specifically, training is providing education to acquire certain competencies and skills, whereas support is supervision and mentoring.10 A lack of training and support has limited the capacity of these frontline workers to safely and effectively carry out their responsibilities and has hindered program expansion.8–11

Training and support for CHWs are a concern worldwide.8–12 A systematic review by the World Health Organization revealed widespread, significant gaps in CHW training and support internationally in supervision, certification, content, and continuing education.12 A review by the United States Agency for International Development revealed that the three primary factors impacting CHW ability to provide quality services are as follows: (1) a lack of knowledge and competency, (2) inadequate structure and context, and (3) attitudinal (i.e., inability to express opinions about work).8 In the United States (U.S.), only 18 (36.0%) states have any training or certification program, varying from formal class work to volunteer hours.13 Of these 18 states, few require continuing education (n = 6), recertification (n = 6), or supervision by a health care professional (n = 4).13 Some of these barriers are being addressed by proposed legislation for tighter CHW certification laws or processes in several U.S. states.13 Internationally, protocols have been recommended at a national level for better standardization and supervision.12

Some organizations and investigators have provided online modules or training by telemedicine for CHWs to improve accessibility.14–16 Telemedicine is a growing but underdeveloped arm of electronic health care that has delivered virtual services, including patient care, medical education, and staff training, from one geographical location to another in a fiscally conservative way.14,17–19 The U.S.-based international program, Project ECHO (Extension for Community Health Care Outcomes) has successfully run multiple telemedicine (e.g., telementoring videoconferencing) programs for clinicians practicing in rural areas20 and resource-poor countries.21

Expanding the use of telemedicine for CHWs has the potential to address training gaps, assist in program expansion, and provide safer patient care. However, there is a dearth of studies that report on the use of telemedicine for training CHWs and none that utilize it for ongoing support. One telemedicine CHW training study consisted of a 6-month diabetes tele/videoconferencing training for 23 CHWs, resulting in increased disease knowledge and high participant satisfaction.14 Other U.S. state and university programs have provided distance learning for CHW certifcations.15,16

In the current study, investigators addressed gaps in training and support by utilizing telemedicine for CHWs who led diabetes group visits for low-income Latinos. Specifically, CHWs received weekly training and health care professional support (physician) using ZOOM technology (San Jose, CA)—an audio- and videoconferencing provider.22 The study hypothesis was that this virtual training and support would be feasible and acceptable as measured by telemedicine's usability,23 improvement of baseline to 6-month CHW knowledge of diabetes,24 and program satisfaction.16

Materials and Methods

This was a feasibility and acceptability study to evaluate the efficacy of training and support by telemedicine videoconferencing for CHWs. The CHWs who participated in this training led diabetes group visits for low-income Latinos in Houston, Texas. The Institutional Review Board at Baylor College of Medicine approved the study (H-40322).

Potential CHWs were recruited from a group of individuals who participated in the investigators' pilot diabetes group visit study.25 Recruitment also occurred by word of mouth or from a pool of clinic volunteers. Eligible CHWs received and maintained Texas certifications, were self-identified as Latino(a), and spoke fluent Spanish. To obtain CHW certification, the state of Texas requires 160 h of training or a history of 1,000 h of service in the community 6 years before application.16 To maintain CHW certifications, CHWs must complete 10 formal and informal hours (total n = 20) of continuing education biennially.16 Since the current study was a feasibility and acceptability investigation, sample size calculations and power analyses were not necessarily warranted.26 However, the number of participants must be large enough to assess the measure of feasibility and they must represent the target population.26 Investigators agreed that a goal sample size of six CHWs who reflected low-income Latino community individuals (i.e., socioeconomic status, education, area of residence) would sufficiently assess the feasibility and acceptability of using telemedicine for training and support as measured by usability, knowledge, and satisfaction.

In the current study, CHWs led 3-h, monthly diabetes group visits for 6 months. The structure of the group visits was based on the investigators' prior study described elsewhere.25 Briefly, each group visit (n = 23 patients) consisted of large group education and three small group sessions. Each month, the large group focused on different diabetes-related educational topics (i.e., nutrition, medication adherence). The two CHW-led small groups (social, behavioral) addressed barriers to the monthly topic. For example, during the nutrition month, the social group focused on transportation or financial barriers to obtaining healthy foods. The behavioral medicine group focused on topics from the Problem Areas in Diabetes Questionnaire.27 In addition, a physician addressed diabetes management (i.e., medication titration) in the third small group. CHWs received close supervision by the study principal investigator (PI) during each class. Group visits consisted of 23 Latino(a) patients and were taught in Spanish. They were held at a community clinic that serves low-income (at or below 150% federal poverty level), uninsured patients.

In between the monthly classes, CHWs contacted 3–4 assigned patients from the group visit each week. The purpose of this weekly contact was to offer general encouragement, notify the study physician if there were any acute issues (i.e., hypo- or hyperglycemia), and communicate patient needs that could not wait until the next class (i.e., refills). CHWs provided a report to the study physician each week during their meetings and received feedback from that report. In acute situations, they contacted the study physician in between meetings.

In the current investigation, CHWs were trained and supported using telemedicine (videoconferencing). A bilingual physician who is also a certified Texas CHW instructor led the meetings. Sessions were conducted in English and in Spanish. Meetings were weekly for 1 h in the following format: PART ONE (support) focused on CHW questions and addressing their patient issues (15 min) and PI updates and announcements (15 min). PART TWO focused on diabetes training and didactic teaching (30 min). All CHW meetings were conducted remotely using ZOOM technology, a telemedicine system that has been successful in prior investigations and training interventions.17,20,21 ZOOM is encrypted, secured, and efficient in low-bandwidth settings.22 Meeting participants have face-to-face interaction while simultaneously viewing word processing applications (i.e., PowerPoint®), a white board, or text messaging. Each CHW had broadband internet access and a computer or tablet with a camera, microphone, and the ability to view word processing documents. In addition, CHWs had smart phones to assess telemedicine's usability on these devices.

Based on prior literature suggesting that CHWs receive at least 24 h of annual training28 or 2 h per month, investigators provided 2 h of formal training and 2 h of support monthly. The training paralleled the group visit topics and incorporated teaching skills (e.g., counseling techniques and strategies in behavioral change) (Table 1) and was approved by the state of Texas Department of State Health Services. The curriculum was based on the text, Living a Healthy Life with Chronic Conditions.29 The text consists of 19 chapters that address general diabetes care, medication adherence, nutrition, preventive care, disease complications/comorbidities (i.e., sexual dysfunction, depression), and exercise.29 It provides information for nonhealth care professionals (e.g., CHWs) who have been trained as facilitators to assist in teaching patients about their chronic disease.29 International programs that have utilized the text have shown strong evidence for efficacy in disease insight.30

Table 1.

Community Health Worker Training and Patient Education Topics by Month

| LARGE GROUP (BOOK CHAPTER(S))29 | CHW GROUP 1 SOCIALa | CHW GROUP 2 BEHAVIORAL MEDICINE26,a |

|---|---|---|

| Month 1. Diabetes overview (1,2,18) Defining diabetes and A1c Goal A1c levels Preventing complications |

Taking ownership Glucometer teaching |

Fear and diabetes |

| Month 2. Medication adherence (13) Why nonadherence is common Normal blood sugar levels Overcoming nonadherence |

Taking medications | Worry and diabetes |

| Month 3. Nutrition (11–12) Why nutrition is important How to simplify nutrition Setting goals |

My plate.gov37 | Overwhelmed and diabetes: Taking up too much energy |

| Month 4. Preventive care (18–19) Rationale for preventive care Preventing diabetes complications Age-appropriate preventive care |

Reviewing age-appropriate guidelines | Coping with diabetes complications |

| Month 5. Sex, depression, and diabetes (4,10) Diabetes complications relating to sexual intimacy and depression Importance of glucose control |

Counseling opportunities | Diabetes and depression |

| Month 6. Exercise (6–8) Why exercise is important Why exercise seems difficult How to simplify exercise |

At-home exercise examples | Exercises for the mind |

| Social group general outline: 1. Defining social group topic 2. Identifying barriers and rationale 3. Strategies to overcome barriers including goal setting | ||

| Behavioral medicine group outline: 1. Connection between the mind and body 2. Defining topic in general and its relationship with diabetes 3. Strategies including goal setting to overcome barriers | ||

Goal setting addressed throughout the course in social and behavioral small groups.

CHW, community health worker.

The Telehealth Usability Questionnaire23 was used to measure feasibility and acceptability. It is a 21-question survey designed to evaluate computer-based, person-to-person interactions.23 Items are ranked on a five-item scale (definitely disagree to definitely agree). The questionnaire is divided into six subsections: (1) usefulness (3 questions), (2) ease-of-use (3 questions), (3) interface quality (4 questions), (4) interaction quality (4 questions), (5) reliability (3 questions), and (6) satisfaction and future use (4 questions). Each of these variables has shown good to excellent internal consistency (standardized Cronbach's coefficient alpha 0.81–0.93).23 Feasibility of training conducted by telemedicine was also evaluated by change of CHW knowledge and satisfaction. CHW knowledge was assessed at baseline and 6 months using the Diabetes Knowledge Test, a 23-item survey to evaluate a general understanding of diabetes.24 Psychometric properties of the Diabetes Knowledge Test include factor structure, reliability (0.89), and validity.31

Acceptability was evaluated by CHW satisfaction as measured by the Texas Department of State Health Services survey.16 This post-training evaluation consists of 10 questions related to the quality of training on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = poor, 6 = excellent). There are three additional open-ended questions to provide information on how the training relates to one's work, suggestions for future topics, and general comments.16 In addition, open-ended, written questionnaires and verbal surveys were conducted at 6 months to gather descriptive data.

Data were analyzed in Sigma Plot® 12.0. The Shapiro– Wilk test was used to test normality. For the Telehealth Usability Questionnaire, categories of agreement were converted to numerical values from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree). For the Diabetes Knowledge Test, paired t-tests were used to determine the change of correct responses from baseline to 6 months. Investigators used descriptive statistics to evaluate open-ended survey responses. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the six CHWs involved in this training program are described in Table 2. Most participants were female and all completed high school. Several completed some or all of college. CHWs were born either in Texas or Central America and were typically bilingual. All had full- or part-time work outside of the current study. The average age was 47.3 years (range 30–62). CHWs primarily lived in low-income Latino communities. CHW retention in the current study was 100%.

Table 2.

Baseline Community Health Worker Demographics (n = 6)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 2 (33.33) |

| Education | |

| High school | 2 (33.3) |

| Junior college | 1 (16.67) |

| Some college | 1 (16.67) |

| Completed college | 2 (33.33) |

| Language | |

| Bilingual (English/Spanish) | 5 (83.33) |

| Spanish only | 1 (16.67) |

| Birth origin | |

| U.S. (Texas) | 2 (33.33) |

| Central America | |

| El Salvador | 1 (16.67) |

| Guatemala | 1 (16.67) |

| Mexico | 2 (33.33) |

| Work | |

| Occupation | |

| Construction | 1 (16.67) |

| Medical | 2 (33.33) |

| Ministerial/pastoral | 2 (33.33) |

| Student | 1 (16.67) |

| Full-time | 5 (83.33) |

| Part-time | 1 (16.67) |

| Average (SD) | |

| Age | 47.3 (±10.37) |

| Residential demographics38 | |

| Median income ($) | 44,824 (±11,051) |

| (%) Below federal poverty level | 16.9 (±4.05) |

| (%) Hispanic | 44.8 (±11.27) |

| (%) High school graduates | 79.5 (±7.04) |

SD, standard deviation.

In the Telehealth Usability Questionnaire, CHWs ranked the following categories related to their training and support by telemedicine: usefulness (4.9/5.0, ±0.3), ease of use (4.7/5.0, ±0.1), interface and interaction quality (4.6/5.0, ±0.5; 4.7/5.0, ±0.52, respectively), reliability (4.0/5.0, ±0.6), and satisfaction and future use (4.9/5.0, ±0.1). The Texas Department of State Health Services survey revealed high satisfaction with the content of training (5.8/6.0, ±0.5), excellent instructor training ability (5.8/6.0, ±0.4), and expertise (5.8/6.0, ±0.4). CHWs stated that the objectives were met (n = 4 questions, average 5.8/6.0, ±0.4), the training substantially increased their knowledge and interest in diabetes (5.7/6.0, ±0.5; 5.8/6.0, ±0.4, respectively), and that it was relevant to their job (5.5/6.0, ±1.2).

The Figure 1 illustrates pre- and posttest findings for the Diabetes Knowledge Test. The average score improved from pre- to posttest (15.8 ± 1.3; 21.8 ± 1.2, p < 0.001, respectively) and all CHWs increased their scores (range 4–8 points) from baseline to 6 months. The most commonly missed items on the pretest related to specific questions about diet, complications (i.e., symptoms of diabetic ketoacidosis), and disease management (i.e., mechanisms of insulin, importance of checking glucose when sick).

Fig. 1.

Community health worker baseline and 6-month Diabetes Knowledge Test outcomes (total possible n = 23). CHW, community health worker.

Descriptive data revealed that all (n = 6) CHWs preferred training and support by telemedicine in lieu of prior in-person sessions and liked meeting each week. All also agreed that training and support by telemedicine were beneficial in addressing pressing patient needs, rather than waiting until the next in-person visit with the study physician. Since all (n = 6) CHWs lived more than 20 min from the study site, they favored the convenience of meeting remotely. All (n = 6) would not have been able to attend a weekly meeting otherwise due to work (n = 4), school (n = 1), or family commitments (n = 1). When comparing telemedicine on a laptop, tablet, or smart phone, all devices were feasible. However, CHWs noted that laptops and tablets had larger viewing windows.

Discussion

This study evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of CHW training and support by using telemedicine (videoconferencing). Results revealed that this modality was both feasible and acceptable as measured by its usability (Telehealth Usability Questionnaire23), improvement of baseline to 6-month CHW knowledge of diabetes (Diabetes Knowledge Test24), training satisfaction (Texas Department of State Health Services survey16), and descriptive data. These findings are significant because obtaining a mechanism to provide ongoing, economical training and support is vital to overcome major barriers to quality CHW services, including knowledge, competency, structural, contextual, and attitudinal.8 The current investigation is consistent with a small body of literature demonstrating successful CHW training by utilizing telemedicine.14,17 It is the first study to report the use of telemedicine for ongoing CHW support.

Although telemedicine use for CHW training and support is in its infancy, it has been described in a number of investigations, including other health staff education or training and patient encounters.18–21 Telemedicine is particularly attractive in low-income settings and developing countries as it is not resource intensive or technically challenging.19,21 Since the telemedicine source (ZOOM)22 functioned at a low bandwidth, participants experienced minimal connection problems. Although bandwidth speeds are variable particularly in resource-poor countries,32 there have been multiple studies demonstrating successful telemedicine projects (i.e., videoconferencing) in developing countries.19,21,33,34 This ease of use is consistent with other studies that have utilized virtual training and support.18–21 Furthermore, although CHWs found that laptops and tablets had larger viewing windows than smart phones, they agreed that all were acceptable, which are important budget and flexibility (i.e., device availability) considerations.

Telemedicine's ease of use inherently provides a platform for more accessible and reliable training and support, resulting in the ability to overcome current CHW program barriers. To overcome knowledge and competency barriers, sustainable and standardized training is critical. Telemedicine's convenience and lack of logistical constraints to in-person meetings likely explain why the results of the Telehealth Usability Questionnaire overwhelmingly favored virtual training. The CHWs in the current study would not have been able to meet on a weekly basis without telemedicine. Although the current study occurred in an urban setting, Houston is the fourth largest city in the U.S. and total transportation times could exceed several hours pending traffic. Training requires the availability of both the trainee and trainer. Some CHW programs, particularly in low-income areas, may not have a local expert to train on a topic or skill, resulting in prolonged wait times or inadequate training. Telemedicine bridges these transportation and geographical barriers.

Telemedicine's reliability assists in overcoming the structural and contextual barriers. Inadequate support is a common pitfall in CHW programs and is critical for building high-quality programs.17 During PART ONE (support) of the weekly meetings, CHWs relayed patient questions or concerns that occurred during their weekly communication. Investigators did not observe CHWs “guessing” or giving wrong information to patients, an important safety piece. This discernment is likely attributed to ongoing, reliable training in addition to weekly support that included physician feedback on their patient reports. The significant increase from baseline to 6-month Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire supports this hypothesis.

Furthermore, to overcome attitudinal barriers, CHWs must have opportunities to provide feedback related to their work environment.18 Investigators found that the first 15 min of PART ONE (support) was particularly beneficial for CHWs to express their opinions. CHWs often raised concerns about the class, many times making pivotal changes for improved efficiency. Historically, CHW programs have faced high turnover rates.8,12,35 Prior investigations have revealed the importance of CHW opportunities to voice concerns related to workload, adequate supplies, organization of tasks, and respect.36 They have emphasized that CHWs should be involved in the decision-making processes and incorporated as part of the leadership team.25,36

Although the study is limited by size and in one locale, we attribute the application of these principles to the lack of attrition of CHWs. To increase generalizability, future research is warranted to expand the number of CHW participants. Research is also warranted in resource-poor countries, where low-literacy rates are often problematic, to ascertain and maintain CHW competencies and skills.

Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that telemedicine is a promising modality to provide CHW training and support. Telemedicine's logistical ease and low cost provide a platform for increased CHW training and support availability, thereby decreasing multiple program barriers, including knowledge, competency, structural, contextual, and attitudinal. Future investigations are needed to explore telemedicine for CHW training and support in rural settings and resource-poor countries and to expand to other chronic diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to San Jose Clinic (Houston, TX), which hosted the diabetes group classes. They also wish to thank the CHWs who participated in this study. Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases [Federal Award Identification No.-K23DK11034]. This investigation is part of an ongoing clinical trial NCT03394456, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03394456. Additional support is provided to Dr. Naik by the Houston VA Health Services Research and Development Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety (CIN 13-413) at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Jackson CS, Gracia JN. Addressing health and health-care disparities: The role of a diverse workforce and the social determinants of health. Public Health Rep 2014;129(suppl 2):57–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Furino A. Community Health Worker national workforce study. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professionals, 2007

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Addressing chronic disease through Community Health Workers: A policy and systems-level approach, 2nd ed. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC's Division of Diabetes Translation Community Health Workers/Promotores de Salud: Critical connections in communities. Atlanta: Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002.

- 5. Norris SL, Chowdhury FM, Van Le K, Horsley T, Brownstein JN, Zhang X, Jack L Jr, Satterfield DW. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of persons with diabetes. Diabet Med 2006;23:544–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL Jr, Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010–2025. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:503–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lehmann L, Sanders D. Community health workers: What do we know about them? The state of the evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using Community Health Workers. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 8. United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Factors impacting the effectiveness of Community Health Worker behavior change: A literature review. Washington, DC: USAID, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 9. USAID. Community and formal health system support for enhanced Community Health Worker performance. Washington, DC: USAID, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lopes SC, Cabral AJ, de Sousa B. Community Health Workers: To train or to restrain? A longitudinal survey to assess the impact of training Community Health Workers in the Bolama Region, Guinea-Bissau. Hum Resour Health 2014;12:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scott K, Beckman SW, Gross M, Parlyo G, Rao KD, Cometto G, Perry HB. What do we know about community-based health worker programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on Community Health Workers. Hum Resour Health 2018,16:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization (WHO) Global Health Workforce Alliance. Global experience of Community Health Workers for delivery of health related millennium development goals: A systematic review, country case studies, and recommendations for integration into national health systems. Geneva: WHO, 2010

- 13. Association of State and Territorial Health Offices. Community Health Workers training/certification standards current status. http://www.astho.org/Public-Policy/Public-Health-Law/Scope-of-Practice/CHW-Certification-Standards (Accessed 21November2018)

- 14. Colleran K, Harding E, Kipp BJ, Zurawski A, MacMillan B, Jelinkova L, Kalishman S, Dion D, Som D, Arora S. Building capacity to reduce disparities in diabetes: Training Community Health Workers using an integrated distance learning model. Diabetes Educ 2012;38:386–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Community Health Worker Training Center. Training Offered. Available at https://nchwtc.tamhsc.edu/training-offered (last accessed November21, 2018)

- 16. Texas Department of State Health Services. Community Health Workers: Promotor (a) or Community Health Worker training and certification program. Available at https://dshs.texas.gov/mch/chw/Community-Health-Workers_Program.aspx (last accessed November21, 2018)

- 17. Bouchonville MF, Hager BW, Kirk JB, Qualis CR, Arora S. Endo ECHO improves primary care provider and Community Health Worker self-efficacy in complex diabetes management in medically underserved communities. Endocr Pract 2018;24:40–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sood S, Mbarika V, Jugoo S, Dookhy R, Doarn CR, Prakash N, Merrell RC. What is telemedicine? A collection of 104 peer-reviewed perspectives and theoretical underpinnings. Telemed J E Health 2007;13:573–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schuttner L, Sindano N, Theis M, Zue C, Joseph J, Chilengi R, Chi BH, Stringer JS, Chintu N. A mobile phone-based, Community Health Worker program for referral, follow-up, and service outreach in Rural Zambia: Outcomes and overview. Telemed J E Health 2014;20:721–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scott JD, Unruh KT, Catlin MC, Merrill JO, Tauben DJ, Rosenblatt R, Buchwald D, Doorenbos A, Towle C, Ramers CB, Spacha DH. Project ECHO: A model complex, chronic care in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. J Telemed Telecare 2011;18:481–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lopez MS, Baker ES, Milbourne AM, et al. Project ECHO: A telementoring program for cervical cancer prevention and treatment in low-resource settings. J Glob Oncol 2017;3:658–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. ZOOM. Available at https://www.zoom.us (last accessed November21, 2018)

- 23. Parmanto B, Lewis AN Jr, Graham KM, et al. Development of the Telehealth Usability Questionnaire (TUQ). Int J Telerehabil 2016;8:3–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fitzgerald JT, Funnell MM, Anderson RM, et al. Validation of the revised brief diabetes knowledge test (DKT2). Diabetes Educ 2016; 42:178–187. (last accessed November21, 2018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vaughan EM, Johnston CA, Moreno JP, et al. Integrating CHWs as part of the team leading diabetes group visits: A randomized controlled feasibility study. Diabetes Educ 2017;43:589–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: The what, why and how. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McGuire BE, Morrison TG, Hermanns N, et al. Short-form measures of diabetes-related emotional distress: The Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale (PAID)-5 and PAID-1. Diabetologia 2010;53:66–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Curtale F, Siwakoti B, Lagrosa C, et al. Improving skills and utilization of community health volunteers in Nepal. Soc Sci Med 1995;40:1117–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lorig K, Holman H, Sobel D, et al. Living a healthy life with chronic conditions, 4th ed. Boulder: Bull Publishing Company, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cheng JJ, Arenhold F, Braakhuis AJ. Determining the efficacy of the chronic disease self-management programme and readability of ‘living a healthy life with chronic conditions’ in a New Zealand setting. Intern Med J 2016;46:1284–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hess GE, Davis WK. The Validation of a Diabetes Patient Knowledge Test. Diabetes Care 1983;6:591–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Combi C, Pozzani G, Pozzi G. Telemedicine for developing countries. Appl Clin Inform 2016;7:1025–1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Latifi R, Gunn JK, Bakiu E, et al. Access to specialized care through telemedicine in limited-resource country: Initial 1,065 teleconsultations in Albania. Telemed J E Health 2016;22:1024–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rey-Moreno C, Reigadas JS, Villalba EE, et al. A systematic review of telemedicine projects in Colombia. J Telemed Telecare 2010;16:114–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Khan SH, Chowdhury AM, Karim F, et al. Training and retaining Shasthyo Shebika: Reasons for turnover of Community Health Workers in Bangladesh. Health Care Superv 1998;17:37–47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jaskiewicz W, Tulenko K. Increasing Community Health Worker productivity and effectiveness: A review of the influence of the work environment. Hum Res Health 2012;10:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. United States Department of Agriculture. Choose My Plate. Available at https://www.choosemyplate.gov (last accessed November21, 2018)

- 38. United States Census Bureau. Community Facts. Available at https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml (last accessed November21, 2018)