Abstract

Background

Amebiasis, which is caused by Entamoeba histolytica, is a re-emerging public health issue owing to sexually transmitted infection (STI) in Japan. However, epidemiological data are quite limited.

Methods

To reveal the relative prevalence of sexually transmitted E. histolytica infection to other STIs, we conducted a cross-sectional study at a voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) centre in Tokyo. Seroprevalence of E. histolytica was assessed according to positivity with an ELISA for E. histolytica-specific IgG in serum samples collected from anonymous VCT clients.

Results

Among 2083 samples, seropositive rate for E. histolytica was 2.64%, which was higher than that for HIV-1 (0.34%, p<0.001) and comparable to that for syphilis (rapid plasma reagin (RPR) 2.11%, p=0.31). Positivity for Chlamydia trachomatis in urine by transcription-mediated amplification (TMA) was 4.59%. Seropositivity for E. histolytica was high among RPR/Treponema pallidum hemagglutination (TPHA)-positive individuals and it was not different between clients with and without other STIs. Both seropositivity of E. histolytica and RPR were high among male clients. The seropositive rate for anti-E. histolytica antibody was positively correlated with age. TMA positivity for urine C. trachomatis was high among female clients and negatively correlated with age. Regression analysis identified that male sex, older age and TPHA-positive results are independent risk factors of E. histolytica seropositivity.

Conclusions

Seroprevalence of E. histolytica was 7.9 times higher than that of HIV-1 at a VCT centre in Tokyo, with a tendency to be higher among people at risk for syphilis infection. There is a need for education and specific interventions against this parasite, as a potentially re-emerging pathogen.

Keywords: parasitology, epidemiology, tropical medicine, diagnostic microbiology, public health, sexual medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to examine the seroprevalence of Entamoeba histolytica at a voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) centre in Tokyo, where active surveillance for E. histolytica infection is lacking, including among asymptomatically infected individuals.

This was a cross-sectional study of anonymous clients at a VCT centre. Thus, comparisons are possible of the seroprevalence of E. histolytica with other sexually transmitted infections.

We could not assess risk behaviour or sexual behaviour and cannot exclude the possibility of selection bias among VCT centre clients.

Introduction

Amebiasis is an enteric protozoa infection caused by Entamoeba histolytica. Up to 80% of E. histolytica infections are asymptomatic but persistent; the remainder result in the development of invasive diseases such as colitis and liver abscess.1 Asymptomatically infected individuals represent a risk to the community because they are a source of new infections. Transmission occurs via the oral–faecal route. It has long been believed that amebiasis is only endemic in developing countries where food and water are frequently contaminated with human faeces, or that it occurs among travellers to or immigrants from these countries.1 2 However, in the previous two decades, it has been reported that cases of amebiasis have been rapidly increasing and have become a re-emerging infectious disease not only in developed countries of East Asia but also in European developed countries.3–12 Human-to-human transmission occurs via direct sexual contact, such as oral–anal sexual contact and contact among men who have sex with men in these countries.13 14 Under such circumstances, it is essential to identify individuals who are asymptomatic but chronically infected with E. histolytica and who thus represent sources of new infection, for the epidemiologic control of sexually transmitted E. histolytica infection. However, little epidemiological data are currently available in Japan, other than that from National Epidemiological Surveillance of Infectious Diseases (NESID), which only reports clinically diagnosed ‘symptomatic’ cases. Moreover, it is critical to understand the epidemiology of sexually transmitted E. histolytica infection before the upcoming Tokyo Olympics in 2020, which could serve as a source of the rapid spread of such neglected communicable diseases.

The aim of this study was to investigate the seroprevalence of E. histolytica at a voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) centre in Tokyo, in comparison with the prevalence of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In addition, we discuss future strategies for the epidemiologic control of sexually transmitted E. histolytica infection.

Methods

Setting

Tokyo, the capital city of Japan, is located on the Pacific on the eastern coast of Honshu, the largest of the four main islands comprising Japan. According to the national surveillance system, the annual number of HIV tests performed and the incidence rates of HIV infection are higher in Tokyo than those of other prefectures.15 The Tokyo Metropolitan Minami Shinjuku Testing—Counselling Center is the largest HIV testing centre in Tokyo, and it is very close to a town in Shinjuku with a large population of men who have sex with men (MSM).16 Because there are more MSM who visit this centre to undergo testing for HIV and other STIs, the incidence rate of HIV infection at this centre is higher than that of other public health centres in Tokyo.17

Study population, samples and ethics issues

The design of this study was a cross-sectional study. The total 2083 serum samples used in this study were collected at the Tokyo Metropolitan Minami Shinjuku Testing—Counselling Center where more than 10 000 anonymous clients seek HIV-1 screening tests each year. Collected samples are transferred to the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Public Health for laboratory testing, then stored at 4°C. Fourth-generation HIV-1 screening is performed routinely throughout the year. However, in 2 months of the year (eg, June and December in the case of 2017), the Tokyo Metropolitan Government intensifies STI screening, and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and Treponema pallidum hemagglutination (TPHA) tests for syphilis screening are additionally performed for all clients. In addition, urinary sampling and transcription-mediated amplification (TMA) assay testing for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are performed for clients who are willing to undergo these tests. Therefore, we assessed the seroprevalence of anti-E. histolytica antibody using stored serum samples collected in June and December 2017 and compared this with the positivity for other STIs in this study. In this study, there was no selection bias or missing data.

All protocols for this study were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Laboratory testing

The presence of anti-E. histolytica antibody was detected using a commercially available ELISA kit (E. histolytica IgG-ELISA; GenWay Biotech, Inc). All procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, diluted serum samples (100× dilution in IgG sample diluent) as well as 5 control samples, consisting of 1 substrate blank, 1 negative control, 2 cut-off controls and 1 positive control, were applied to 96-well plates pre-treated with E. histolytica antigen and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. After washing the plates using washing solution, 100 µL of E. histolytica Protein A conjugate was added to all wells except the substrate blank and incubated for 30 min in the dark. After a second wash, 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine substrate solution was added to all wells. After a 15 min incubation, 100 µL of stop solution was applied to the plates, and absorbance of the specimen was then read at 450/620 nm using a spectrometer.

Statistical analysis

Of the total samples tested in each STI screening test, the proportion of seropositive blood and urine samples is presented with 95% CIs calculated using the Wilson-Brown method. The seroprevalence of E. histolytica was compared with that of other STIs using Fisher’s exact test. To determine the trend of seropositivity among age groups, we used the χ2 test for trend. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p value<0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software). Logistic regression analysis for identification of factors influencing E. histolytica seropositivity was performed using Stata (StataCorp LLC).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the design and conduct of this research.

Results

Study population and seroprevalence of E. histolytica at a VCT centre in Tokyo

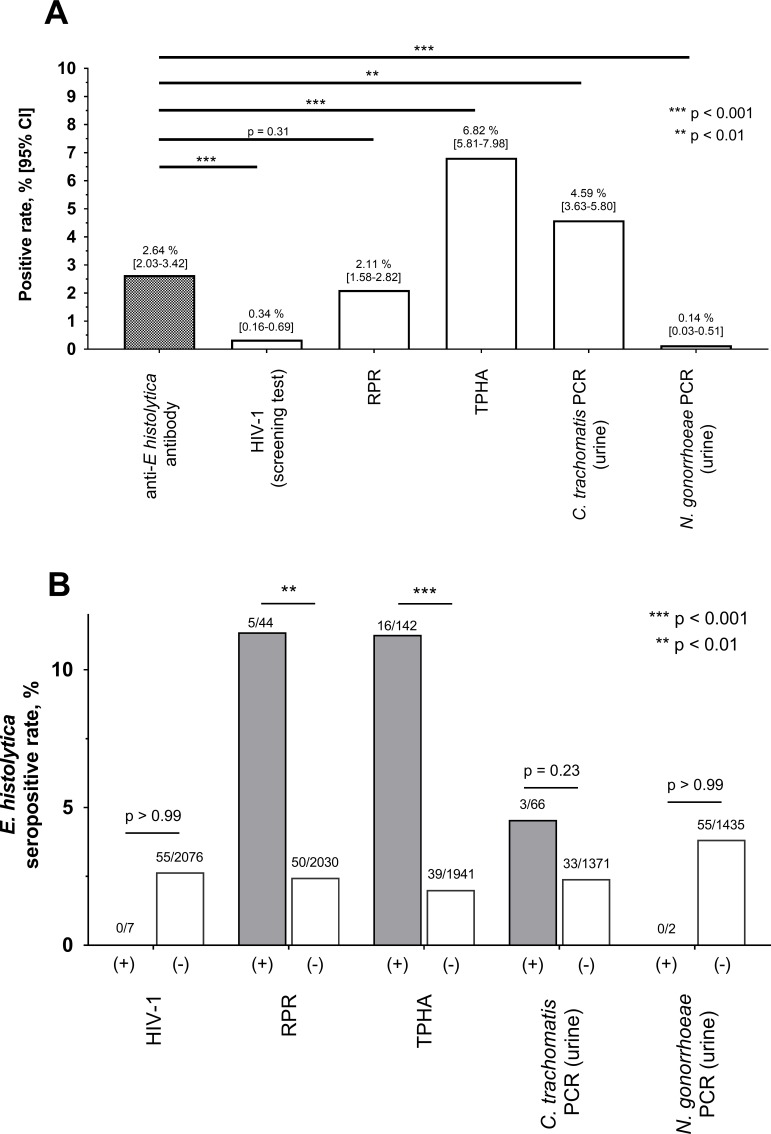

In total, 2083 samples were analysed. The average age of clients was 35.2 (95% CI: 34.8 to 35.7) years, and 70.8% (1474/2083) were men (figure 1). The overall seropositive rate for E. histolytica was 2.64%; this was significantly higher than that for HIV-1 (0.34%) and the comparable level as that for syphilis by RPR (2.11%) (figure 2A). The positive rate of urinary TMA for C. trachomatis (4.59%) was higher than that for E. histolytica; however, urinary TMA testing for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae was only carried out in 69.0% (1437/2083) of clients, that is, those who were willing to undergo TMA testing. These results suggest that E. histolytica is a more common STI than HIV-1 in Tokyo and is at a level comparable to that of syphilis infection. Interestingly, all individuals who were seropositive for E. histolytica were seronegative for HIV-1 (figure 2B). Furthermore, the seropositive rate for E. histolytica was significantly higher among people who were seropositive for syphilis infection (by both RPR and TPHA) than among those who were seronegative for syphilis; no significant differences in E. histolytica seropositivity were seen according to TMA positivity for C. trachomatis. These results indicate that E. histolytica infection is spreading among people at risk for syphilis infection.

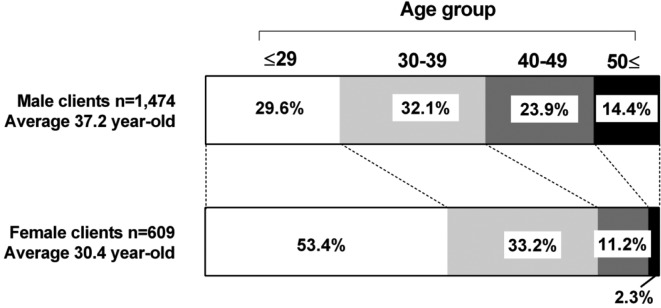

Figure 1.

Proportion of clients in each age group among men and women. The average age among female clients was significantly lower than that in male clients (p<0.001). The proportion of clients aged 29 years or less among female clients was 53.4%, whereas that in male clients was only 29.6%.

Figure 2.

Seropositivity for Entamoeba histolytica and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in Tokyo. Serologic testing results (anti-E. histolytica antibody, HIV-1, RPR and TPHA) were obtained for 2083 clients of a voluntary counselling and testing centre in June and December 2017. Results of urinary TMA for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae were available for 1437 clients who agreed to testing. All statistics were calculated using Fisher’s exact test. (A) The seropositive rate for E. histolytica was compared with those of other STIs. (B) Comparison of seropositivity for E. histolytica, with and without other STIs. RPR, rapid plasma reagin; TPHA, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination; TMA, transcription-mediated amplification.

Differences in seropositivity by sex and age group

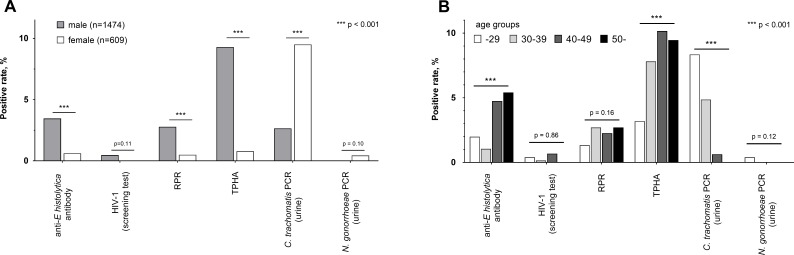

Next, we compared positivity for STIs between male and female clients. The seropositive rate for E. histolytica was significantly higher in male (3.46%) than in female (0.66%) clients, as seen for syphilis infection (RPR: 2.78% vs 0.49% and TPHA: 9.29% vs 0.82%) (figure 3A). The proportion of urinary TMA results positive for C. trachomatis was significantly higher in female (8.77%) than in male (2.65%) clients. However, it is difficult to simply compare the TMA positivity by sex because persistent, asymptomatic C. trachomatis infection of the urinary tract occurs more frequently in women.18–21 Moreover, the age of female clients was significantly lower than that of male clients, and the proportion of clients aged 29 years or less in women was 53.4%, whereas that in men was only 29.6% (figure 1). These results indicate that both male and female clients in this study are at risk for STIs; however, the predominant pathogens might differ between relatively older men (E. histolytica and Treponema pallidum) and relatively younger women (C. trachomatis).

Figure 3.

Positive rate of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) by sex and age group. (A) Positive rate of Entamoeba histolytica and other STIs were compared between male (n=1474) and female (n=609) clients using Fisher’s exact test. (B) Seropositive rates for E. histolytica and RPR, and TMA positivity for Chlamydia trachomatis were calculated for clients of different age groups (serum, urine samples): 29 years or younger (752, 503), 30–39 years (666, 453), 40–49 years (443, 315), and 50s or older (222, 167). Correlation between age and positivity was calculated using the χ2 test for trend. RPR, rapid plasma reagin test; TPHA, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination; TMA, transcription-mediated amplification.

To determine the trend of E. histolytica seropositivity by age, we compared seropositivity for E. histolytica in different age groups. Interestingly, the seropositive rates for anti-E. histolytica antibody and RPR was highest among clients aged 50 years or older (5.41% and 2.70%, respectively). Moreover, a positive correlation was observed between age and seropositivity for E. histolytica (figure 3B). Positive urinary TMA for C. trachomatis was highest among clients aged 29 years or younger (8.35%) and showed a negative correlation with age. These results are consistent with national surveillance data, in which diagnosed cases of Chlamydia infection have a peak in the 20s,22 whereas the median age of reported cases of amebiasis is relatively high (50 years in men and 40 years in women).5 20 Considering these findings, E. histolytica infection might be more prevalent among relatively older age groups (40 years or more), whereas Chlamydia infection is more prevalent in relatively younger populations.

Risk of seropositivity for E. histolytica

Finally, to identify the risk factors of seropositivity for E. histolytica, we compared positivity for STIs between clients who were positive and negative for E. histolytica (table 1). Although there were no statistical differences in the positive rates for HIV-1, C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae, the positive rates for any STIs were higher in clients who were positive for E. histolytica than in E. histolytica-negative clients (30.56% vs 10.49%, p=0.0001). Thus, we performed logistic regression analysis using data of client characteristics and the results of STI screening tests. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses revealed that male sex, a history of syphilis infection (by TPHA) and older age were independent risk factors of seropositivity for E. histolytica (table 2). In particular, age 40 years or older was a high-risk factor of seropositivity for E. histolytica (OR 3.31 in people aged less than 40 years, p value<0.001 by univariate analysis; data not shown). In addition, univariate analysis showed that positive RPR was a high-risk factor for E. histolytica seropositivity; however, this was diminished in multivariate analysis owing to the strong association with TPHA positivity. Univariate analysis using preliminary urinary TMA data of 1437 participants showed that positivity for C. trachomatis in the urine had no impact on E. histolytica seropositivity (table 2). We could not include HIV-1 serology and TMA positivity for N. gonorrhoeae in urine in the logistic regression analyses because no clients who were HIV-1 seropositive or positive for N. gonorrhoeae by TMA were also seropositive for E. histolytica.

Table 1.

Comparison of positive results for other STIs between Entamoeba histolytica seropositive and seronegative clients.

| E. histolytica seropositive | E. histolytica seronegative | P value | |

| Male, % (n) | 92.73% (51/55) | 70.17% (1423/2028) | 0.0001 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 41.6 (12.56) | 35.1 (10.4) | <0.0001 |

| Positive rate, % (n) | |||

| HIV-1 | 0% (0/55) | 0.35% (7/2028) | >0.999 |

| RPR | 9.09% (5/55) | 1.92% (39/2028) | 0.005 |

| TPHA | 29.09% (16/55) | 6.21% (126/2028) | <0.0001 |

| Urine Chlamydia trachomatis (TMA) | 8.33% (3/36) | 4.50% (63/1401) | 0.227 |

| Urine Neisseria gonorrhoeae (TMA) | 0% (0/36) | 0.14% (2/1401) | >0.999 |

| Any of the above STIs | 30.56% (11/36) | 10.49% (147/1401) | 0.0001 |

The positive rate of any of the other STIs was calculated only in clients whose blood and urine were tested.

RPR, rapid plasma reagin; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; TMA, transcription-mediated amplification; TPHA, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination.

Table 2.

Impact of individual characteristics of seropositivity for Entamoeba histolytica, Tokyo.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis* | |||

| OR (95% CI) |

P value | OR (95% CI) |

P value | |

| Sex (male) | 5.42 (1.95 to 15.06) |

<0.001 | 3.17 (1.10 to 9.07) |

0.032 |

| Older age (by 10-year age groups) |

1.66 (1.33 to 2.08) |

<0.001 | 1.49 (1.17 to 1.90) |

0.001 |

| HIV-1 positive | ND† | |||

| Syphilis infection | ||||

| RPR positive | 5.1 (1.93 to 13.49) |

0.006 | 1.26 (0.41 to 3.89) |

0.693 |

| TPHA positive | 6.19 (3.37 to 11.39) |

<0.001 | 4.30 (2.11 to 8.76) |

<0.001 |

| Urine Chlamydia trachomatis (TMA) positive‡ | 1.93 (0.58 to 6.47) |

0.326 | ||

| Urine Neisseria gonorrhoeae (TMA) positive‡ | ND† | |||

*Multivariate analysis for age and sex, plus factors with p<0.05 in univariate analysis.

†ORs could not be determined in logistic regression analysis because all clients who were HIV-1 positive and/or positive for gonorrhoea by TMA were E. histolytica seronegative.

‡Data of urinary TMA testing available only for 69.0% (1437 of 2083) of total clients.

RPR, rapid plasma reagin; TPHA, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination; TMA, transcription-mediated amplification; ND, not determined.

Discussion

The most important finding of this study was that the seroprevalence of E. histolytica was significantly (7.9 times) higher than that of HIV-1 and it was comparable to that for syphilis (by RPR), indicating that E. histolytica is now a potential re-emerging pathogen in our country. Certainly, it is difficult to simply compare seropositivity among these three tests; the HIV-1 screening test continues to be positive for a person’s entire life, whereas positivity in RPR and anti-E. histolytica antibody tests indicate current or recent infection.21 22 However, these results strongly indicate that the endemicity of E. histolytica in Tokyo is higher than that of HIV-1 and close to the level of syphilis. In contrast to our seroprevalence data, the national surveillance data of Japan from NESID pragmatically show that the annual number of diagnosed cases of amebiasis (1151 in 2016) is not only much lower than that of syphilis (4575 cases), it is also lower than that of HIV-1 (1443 cases).22 23 Our results suggest that the endemicity of amebiasis in Japan is currently underestimated, thereby remaining a neglected disease in Japan despite frequently reported life-threatening cases of amebiasis.24–27 Interestingly, in this study, all individuals who were seropositive for E. histolytica were HIV-1 negative, whereas regression analysis identified that seropositivity for syphilis by TPHA was an independent risk factor of a positive result for anti-E. histolytica antibody. Previous reports have emphasised the high seroprevalence of E. histolytica 28 and increasing number of amebiasis cases29–31 among individuals with HIV-1 infection. Although the epidemiological trend of E. histolytica among HIV-1-positive individuals could not be assessed in this study owing to the small number of clients who were positive for HIV-1, it should be noted that sexually transmitted E. histolytica infection is currently spreading even among HIV-1-negative populations, as we indicated in our earlier hospital-based cross-sectional analysis.32 Currently, screening for E. histolytica is not routinely performed at VCT centres in Japan; however, public health interventions should be considered to control sexually transmitted E. histolytica infection.

The clinical significance of seropositivity for E. histolytica remains unclear and is beyond the scope of this paper. Serologic testing is a sensitive diagnostic method for symptomatic invasive amebiasis; however, positive results are also obtained for recent infections, up to the previous several years.25 However, we had reported earlier that 70.4% of E. histolytica-seropositive individuals did not have any amebiasis-related symptoms nor any history of treatment for amebiasis. Interestingly, 20% of such individuals in a Japanese HIV-1 cohort developed symptomatic invasive amebiasis within a 1-year follow-up period.28 In another cross-sectional analysis, we also reported that ulcerative lesions owing to E. histolytica in the large intestine are frequently identified (7/18, 38.9%) by colonoscopy among asymptomatic individuals who are E. histolytica seropositive, whereas these rarely (1/53, 1.9%) occur among E. histolytica-seronegative people.33 Serologic screening for E. histolytica at VCT centres, followed by diagnosis of subclinical E. histolytica infection by colonoscopy and treatment at a referral hospital, is one possible public health strategy against sexually transmitted E. histolytica infection. However, we must assess the utility of serologic testing for the screening of asymptomatic E. histolytica in well-designed prospective analyses in the future.

This study has some limitations that should be considered. First, this preliminary investigation was a cross-sectional study of anonymous clients at a VCT centre. We could not assess risk behaviours, including sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, sanitation and dietary habits, with respect to seropositivity for E. histolytica owing to a lack of detailed data on the characteristics of clients. Therefore, further intensive epidemiological studies are needed, to assist in developing future intervention approaches for this re-emerging infectious disease. In addition, the study periods were 2 months apart owing to the availability of data for not only HIV-1 but also other STIs (serum tests for syphilis and urine tests for chlamydia and gonorrhoea). We could not exclude the possibility of selection bias of clients, such as those who undergo repeat testing. Second, anti-E. histolytica antibody was screened using stored serum. Long periods of storage could lead to lower sensitivity of serologic tests, resulting in underestimation of the seroprevalence of E. histolytica. Third, we obtained a considerably lower seropositive rate for E. histolytica among female clients (0.66%, 4/609) than that among male clients (3.46%, 51/1474). This probably results from the fact that VCT centres may not be appropriate for identifying female populations at high risk for E. histolytica infection; our female clients were relatively younger and had lower seropositive rates in RPR and TPHA tests. More appropriate sampling locations should be identified such as STI clinics that are visited by female commercial sex workers.34

In conclusion, among clients of a VCT centre in Tokyo, seropositivity for E. histolytica was 7.9 times higher than that of HIV-1 and tended to be high among individuals at risk of syphilis infection. Active detection and treatment of asymptomatic cases of E. histolytica infection should be considered for the epidemiologic control of sexually transmitted E. histolytica infection in Japan.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Analisa Avila, ELS, of Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanzgroup.com/?utm_source=ack&utm_medium=journal) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

YY and MN contributed equally.

Presented at: Preliminary results from this study were presented at American Society for Microbiology Microbe 2018, convened 7–11 June 2018, in Atlanta, GA, USA.

Contributors: Conception or design on the work: YY, HG, YK, SO, MN, KY, TS, KS, KW. Data collection: MN, KY, TS, KS. Data analysis and interpretation: YY, MN, KY, TS, KS, KW. Drafting the article: YY, MN, KW. Critical revision of the article: YY, KW. Final approval of the version to be published: YY, HG, YK, SO, MN, KY, TS, KS, KW.

Funding: This work was supported by the Emerging/Re-emerging Infectious Diseases Project of Japan from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development under Grant Number 18fk0108046, and a grant from the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (29-2013).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the ethics committee of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM-2302) and Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Public Health (29-875).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository. Data are available upon reasonable request. Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi: doi:10.5061/dryad.kd51c5b2h.

References

- 1. Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, et al. Amebiasis. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1565–73. 10.1056/NEJMra022710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stanley SL. Amoebiasis. Lancet 2003;361:1025–34. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12830-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hung C-C, Chang S-Y, Ji D-D. Entamoeba histolytica infection in men who have sex with men. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:729–36. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70147-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu H, Wu P-Y, Li S-Y, et al. Maximising the potential of voluntary counselling and testing for HIV: sexually transmitted infections and HIV epidemiology in a population testing for HIV and its implications for practice. Sex Transm Infect 2012;88:612–6. 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ishikane M, Arima Y, Kanayama A, et al. Epidemiology of domestically acquired amebiasis in Japan, 2000-2013. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016;94:1008–14. 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Park WB, Choe PG, Jo JH, et al. Amebic liver abscess in HIV-infected patients, Republic of Korea. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13:516–7. 10.3201/eid1303.060894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stark D, van Hal SJ, Matthews G, et al. Invasive amebiasis in men who have sex with men, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14:1141–3. 10.3201/eid1407.080017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oh MD, Lee K, Kim E, et al. Amoebic liver abscess in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 2000;14:1872–3. 10.1097/00002030-200008180-00033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spinzi G, Pugliese D, Filippi E. An unexpected cause of chronic diarrhea. Gastroenterology 2016;150:e5–6. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Escolà-Vergé L, Arando M, Vall M, et al. Outbreak of intestinal amoebiasis among men who have sex with men, Barcelona (Spain), October 2016 and January 2017. Euro Surveill. 2017;22. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.30.30581. [Epub ahead of print: 27 Jul 2017]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roure S, Valerio L, Soldevila L, et al. Approach to amoebic colitis: epidemiological, clinical and diagnostic considerations in a non-endemic context (Barcelona, 2007-2017). PLoS One 2019;14:e0212791 10.1371/journal.pone.0212791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Timsit BL, Deroux A, Lugosi M, et al. [Amoebosis: May sexual transmission be an underestimated way of contamination?]. Rev Med Interne 2018;39:586–8. 10.1016/j.revmed.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hung C-C, Wu P-Y, Chang S-Y, et al. Amebiasis among persons who sought voluntary counseling and testing for human immunodeficiency virus infection: a case-control study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011;84:65–9. 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lo Y-C, Ji D-D, Hung C-C. Prevalent and incident HIV diagnoses among Entamoeba histolytica-infected adult males: a changing epidemiology associated with sexual transmission--Taiwan, 2006-2013. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014;8:e3222 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ministry of health labor and welfare. Tokyo: AIDS surveillance Committee, 2017. Available: http://api-net.jfap.or.jp/status/2017/17nenpo/17nenpo_menu.html

- 16. Ministry of health labor and welfare. Tokyo: AIDS surveillance Committee, 2017. Available: http://api-net.jfap.or.jp/status/2017/17nenpo/kensa.pdf

- 17. Ministry of health labor and welfare. Tokyo: AIDS surveillance Committee, 2017. Available: http://api-net.jfap.or.jp/status/2017/17nenpo/hyo_09_02.pdf [Accessed 27 Aug 2018].

- 18. Morré SA, van den Brule AJC, Rozendaal L, et al. The natural course of asymptomatic Chlamydia trachomatis infections: 45% clearance and no development of clinical PID after one-year follow-up. Int J STD AIDS 2002;13 Suppl 2:12–18. 10.1258/095646202762226092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wiesenfeld HC. Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis Infections in Women. N Engl J Med 2017;376:765–73. 10.1056/NEJMcp1412935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cecil JA, Howell MR, Tawes JJ, et al. Features of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in male Army recruits. J Infect Dis 2001;184:1216–9. 10.1086/323662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Detels R, Green AM, Klausner JD, et al. The incidence and correlates of symptomatic and asymptomatic Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections in selected populations in five countries. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38:1–9. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318206c288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ministry of Health Law Annual reported cases of sexually transmitted infections in Japan [in Japanese], 2005. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/2005/04/tp0411-1.html [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Institute of Infectious Diseases Infectious Agents Surveillance Report. Annual reported cases of Category V Infectious Diseases in Japan [in Japanese]. Available: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/2005/04/tp0411-1.html [Accessed Sep 2018].

- 24. Goto M, Mizushima Y, Matsuoka T. Fulminant amoebic enteritis that developed in the perinatal period. BMJ Case Rep 2015;361. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-207909. [Epub ahead of print: 25 Jun 2015]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ito D, Hata S, Seiichiro S, et al. Amebiasis presenting as acute appendicitis: report of a case and review of Japanese literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014;5:1054–7. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.10.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kobayashi T, Watanabe K, Yano H, et al. Underestimated amoebic appendicitis among HIV-1-infected individuals in Japan. J Clin Microbiol 2017;55:313–20. 10.1128/JCM.01757-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yamada H, Matsuda K, Akahane T, et al. A case of fulminant amebic colitis with multiple large intestinal perforations. Int Surg 2010;95:356–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Watanabe K, Aoki T, Nagata N, et al. Clinical significance of high anti-entamoeba histolytica antibody titer in asymptomatic HIV-1-infected individuals. J Infect Dis 2014;209:1801–7. 10.1093/infdis/jit815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoshikura H. A strong correlation between the annual incidence of amebiasis and homosexual human immunodeficiency virus type infection in men. Jpn J Infect Dis 2016;69:266–9. 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2015.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ohnishi K, Kato Y, Imamura A, et al. Present characteristics of symptomatic Entamoeba histolytica infection in the big cities of Japan. Epidemiol Infect 2004;132:57–60. 10.1017/S0950268803001389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Watanabe K, Gatanaga H, Escueta-de Cadiz A, et al. Amebiasis in HIV-1-infected Japanese men: clinical features and response to therapy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011;5:e1318 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yanagawa Y, Nagata N, Watanabe K, et al. Increases in Entamoeba histolytica Antibody–Positive rates in human immunodeficiency Virus–Infected and noninfected patients in Japan: a 10-year hospital-based study of 3,514 patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016;95:604–9. 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Watanabe K, Nagata N, Sekine K, et al. Asymptomatic intestinal amebiasis in Japanese HIV-1-infected individuals. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014;91:816–20. 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Suzuki J, Kobayashi S, Iku I, et al. Seroprevalence of Entamoeba histolytica infection in female outpatients at a sexually transmitted disease sentinel clinic in Tokyo, Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis 2008;61:175–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.