Abstract

Objectives

Nursing home (NH) residents experience a high burden of chronic disease. Chronic disease management (CDM) can be a challenge, as the context of care provision and the way care is provided impact care delivery. This scoping review aimed to identify types of chronic diseases studied in intervention studies in NHs, influential contextual factors addressed by interventions and future CDM research considerations.

Design

The scoping review followed guidelines by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien (2010). Six reviewers screened citations for inclusion. Data extraction was performed by one reviewer and verified by a second reviewer.

Data sources

We searched four databases: CINAHL, EMBASE, PubMed and Scopus, in March 2018.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if (1) aim of intervention was to improve CDM, (2) intervention incorporated the chronic care model (CCM), (3) included NH residents, (4) analysed the efficacy of the intervention and (5) sample included adults over age 65 years. Studies were limited to English or French language and to those published after 1996, when the CCM was first conceptualised.

Data extraction and synthesis

Extracted information included the type of chronic disease, the type and number of CCM model components used in the intervention, the method of delivery of the intervention, and outcomes.

Results

On completion of the review of 11 917 citations, 13 studies were included. Most interventions targeted residents living with dementia. There was significant heterogeneity noted among designs, outcomes, and type and complexity of intervention components. There was little evaluation of the sustainability of interventions, including feasibility.

Conclusions

Research was heavily focused on management of dementia. The most commonly included CCM components were multidisciplinary care, evidence-based care, coordinated care and clinical information systems. Future research should include subjective and objective outcomes, which are meaningful for NH residents, for common chronic diseases.

Keywords: chronic disease management, nursing home, scoping review, intervention studies

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A thorough search strategy was devised and conducted in four peer-reviewed databases (CINAHL, EMBASE, PubMed and Scopus).

Reviewers followed an independent, structured review protocol for determining eligibility, extracting results and reporting outcomes.

There is little evidence available to support the development of a comprehensive, chronic disease management care model for older adults requiring complex care, as seen in nursing homes.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic diseases are conditions lasting at least 1 year in duration and, when poorly managed, they can negatively impact the lives of older adults.1 The impact of chronic disease is staggering: 63%–67% of deaths in Canada and the USA are caused by cancer, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases and chronic respiratory diseases.2–4 Dementia, another chronic disease, has become very relevant in caring for ageing populations as it is often responsible for older adults moving to nursing homes (NH).5 NHs are especially impacted by chronic disease, as individuals often need care for several chronic diseases and symptoms, leading to complex care needs and clinical uncertainty and/or difficulty in addressing those needs.6–8

Chronic disease management (CDM) refers to the ongoing care and support provided to individuals living with a chronic disease. To improve care delivery generally, the context in which care is provided and the way care is provided need to be considered. Wagner and colleagues9–11 developed a model (ie, chronic care model ‘CCM’) of external factors to support high-quality CDM including multidisciplinary teams to provide patient care, inclusion of patient self-management techniques, provision of coordinated care, delivery system redesign (to promote improved access to resources), use of clinical information systems (to improve evaluation and communication) and using an evidence-based approach to provide care (see online supplementary appendix A).10 Consequently, studies evaluating interventions for CDM should account for contextual factors to maximise uptake in bedside applications.

bmjopen-2019-032316supp001.pdf (77.4KB, pdf)

A systematic review examining how CDM programme incorporated the CCM10 in interventions for patients in primary healthcare settings showed improved survival and disease control.11 Additionally, primary studies12–14 found that incorporating components of the CCM10 (ie, patient self-management and delivery system redesign) within their interventions improved outcomes for primary care clients living with chronic disease. It would be reasonable to assume that CDM interventions aimed at improving care for residents living in NHs would also be strengthened from incorporating components of the CCM.10

Given the rising demand for NH capacity and quality care delivery, we sought to identify (1) which chronic diseases have been the subject of intervention studies in NHs, (2) what CCM10 components are addressed in CDM interventions for NH residents and (3) what gaps may future research consider to improve CDM in NHs.

Methods

The authors opted to conduct a scoping review to address the study’s objectives. A scoping review aims to map the existing literature in a field of interest in terms of the volume, nature and characteristics of the primary research.15 It is particularly useful for our topic as applications of the CCM10 in CDM interventions in NHs have not yet been extensively reviewed.16 17 This scoping review is presented using a standardised framework used by Tricco and colleagues18 and Daudt and colleagues.19 This scoping review was performed in accordance with Arksey and O’Malley’s15 six-pronged framework and Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien’s20 additional suggestions for reviewing literature. The six-pronged framework15 recommends that the following six steps be taken: identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data, and collating, summarising and reporting results. Additional suggestions11 build on this framework by clarifying each step and providing recommendations to enhance each step.

To be eligible for inclusion in the scoping review, studies were (1) required to evaluate an intervention to improve the management of a chronic disease. In keeping with standard nomenclature, chronic disease was broadly defined as a pathological process of at least 1 year in duration (eg, heart disease and stroke, cancer, diabetes, osteoporosis).1 Additionally, included studies were (2) required to incorporate at least one component of the CCM10 within the intervention. Studies were not required to directly reference the CCM10; when reviewers performed the full-text review, they examined the description of the intervention to determine if it met this requirement indirectly (ie, included a contextual factor described by the CCM)10 or directly (ie, cited the CCM10 within the description of the intervention). The remaining eligibility criteria were as follows: (3) the study aim was specific to residents living in NHs, (4) the analysis included the efficacy of the intervention and (5) the sample included adults over age 65. Studies were limited to English or French language and to those published after 1996, when CCM10 models were first conceptualised.9

A search strategy was devised by combining keywords that described the population, setting, intervention and outcomes of interest in consultation with a librarian, and the strategy was refined based on keywords used in relevant literature (see online supplementary appendix B). Once agreed on by authors, the literature search was conducted in four databases: CINAHL, EMBASE, PubMed and Scopus, in March 2018. Results were catalogued in Mendeley, a reference managing system (version 1.17.13). Duplicates were removed and remaining results were screened for eligibility based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Six authors (grouped in pairs) independently screened an assigned list of titles and abstracts simultaneously between April and July 2018. The same pair of authors then performed full-text reviews of their selected manuscripts between July and August 2018. In cases of uncertainty (titles and abstracts, as well as full manuscripts), a review by all authors occurred until a group consensus was reached. Authors then extracted data (study foci, sample, study design, intervention, outcomes, findings) using a standardised form based on Cochrane’s Systematic Review for Interventions Guidebook.21 Additionally, the type of CCM10 component included in the intervention (eg, multidiscliplinary care, evidence-based care, etc) and the type of activities as part of the intervention (eg, case management, provider education, etc) were recorded (table 1). A second reviewer then verified data extraction. Descriptive statistics were computed using SAS V.9.4 and a thematic analysis22 of outcomes was performed.

Table 1.

Strategies for optimising chronic disease management in nursing homes

| Summary of methods | Count (%) |

| Chronic disease studied | |

| Dementia | 9 (75.0%) |

| Diabetes | 2 (16.7%) |

| Congestive heart failure | 1 (8.3%) |

| Study duration | |

| 2–3 months | 3 (25%) |

| 4–6 months | 3 (25%) |

| >6 months | 1 (8.3%) |

| Not stated | 5 (41.7%) |

| Sample characteristics | |

| Sample age (mean, years) | |

| <80 | 0 |

| 80–85 | 4 |

| >85 | 4 |

| Not stated | 4 |

| Sample size | |

| >100 | 6 |

| 100–200 | 3 |

| >300 | 3 |

| CCM10 components | |

| Multidisciplinary care | 11 |

| Evidence-based care | 10 |

| Coordinated care | 9 |

| Clinical information systems | 8 |

| Delivery system redesign | 2 |

| Patient self-management | 1 |

| Intervention delivery methods | |

| Case management | 5 |

| Provider education | 4 |

| Nursing assessments | 3 |

| Chart review | 2 |

| Consultation | 2 |

| Diagnosis verification | 1 |

| Patient education | 1 |

| Psychotherapy | 1 |

| Recreational activities | 1 |

| Specialised care team | 1 |

| Vaccines | 1 |

| Study design | |

| Randomised controlled trial | 4 (33.3%) |

| Cohort study | 2 (16.7%) |

| Step wedge trial | 2 (16.7%) |

| Cross-sectional survey | 1 (8.3%) |

| Crossover trial with repeated measures | 1 (8.3%) |

| Pilot case study | 1 (8.3%) |

| Repeated measures | 1 (8.3%) |

CCM, chronic care model.

bmjopen-2019-032316supp002.pdf (90.8KB, pdf)

Results

Study selection

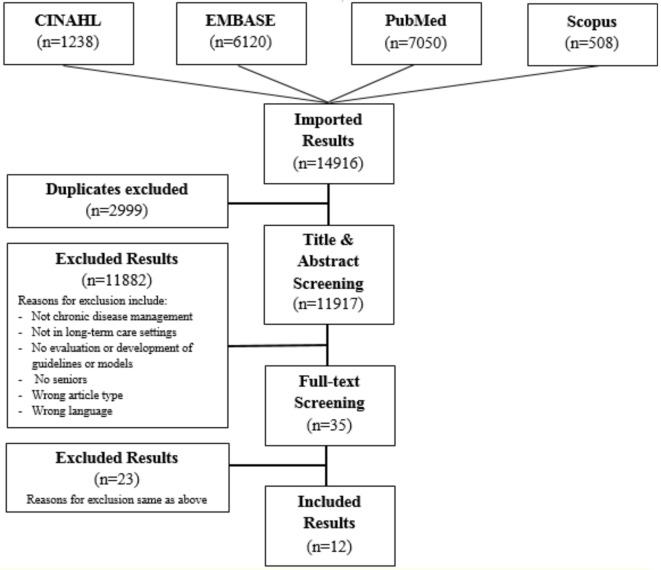

The search generated 14 916 results. On removal of duplicates, 11 917 articles remained. The majority of these (10,517) were excluded during title and abstract screening because they did not include a component of the CCM.10 Of the 38 studies that underwent full-text review, 26 were excluded because they did not meet eligibility criteria. Screening procedures are listed in figure 1. Finally, since the study was conducted in March 2018, one additional study was suggested by a journal editor during the review of the manuscript. The authors reviewed the study and subsequently included it, thus leading to a total of 13 included studies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search.

A total of 13 studies were included (table 2).23–35 These 13 studies were published between 2002 and 2016 (six studies within the last decade). Studies were conducted in the USA (6),23–28 Australia (2),29 30 Canada (2)31 32 and the Netherlands (3).33–35

Table 2.

Study characteristics

| Study characteristics (n=12) | Count (%) |

| Year of publication | |

| 2002–2005 | 5 (41.7%) |

| 2006–2010 | 2 (16.7%) |

| 2010–2015 | 5 (41.7%) |

| Location | |

| USA | 6 (50%) |

| Canada | 2 (16.7%) |

| Australia | 2 (16.7%) |

| The Netherlands | 2 (16.7%) |

Study designs and interventions

Studies’ methodologies varied across chronic diseases, study design and duration, sample selection, number and type of CCM10 components used in the intervention(s), and intervention activities (table 1). The majority of studies (76.9%) focused on management of dementia.23 24 26 27 29–31 33–35 Two studies25 32 focused on managing diabetes mellitus and one study28 evaluated the management of heart failure. The average age of included samples was between 80 and 90 years. Sample size varied from 3 to 659 participants. In total, 12 studies (92.3%) implemented and evaluated multidisciplinary care, guided by a quality assurance framework, to manage care for NH residents living with dementia.23–31 33–35 Interventions were often complex: an average of 3.2+1.2 CDM components were used per study. Other commonly used CDM components were evidence-based care (11 studies),23 25 27–35 coordinated care (nine studies)23 25–27 29–31 33 34 and clinical information studies (eight studies).23 25 27 28 31–34 Intervention delivery methods included case management (five studies),25 28 29 32 35 provider education (six studies),25 27 28 31 33 35 nursing assessments (four studies),25 27 28 35 chart review (seven studies),25 28 29 31 32 34 35 consultation (three studies)29 30 35 and psychotherapy (two studies).29 35 Unique strategies included, recreational activities,26 specialised care teams,25 vaccines,28 diagnosis verification28 and patient education.28 Study designs included randomised controlled trials (RCTs; three studies),24 27 29 cohort studies (two studies),28 31 step wedge trials (two studies)30 34 and others (six studies).22 24 25 31 32 34 Studies ranged from 2 months to 20 months.

Study metrics

Several metrics were employed by studies targeting dementia management. Behaviours were the most commonly assessed outcome (n=5), followed by agitation and depression (n=4), and psychosis or neuropsychiatric symptoms (n=4). Behaviours were assessed using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory,29 33 35 the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory,24 26 30 33–35 the Behavioural Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale,29 the Nursing Home Behaviour Problems Scale31 and a modified form of the Behaviour Assessment Graphical System.30 Other outcomes studied included positive and negative affect using the Philadelphia Geriatric Centre Affect Rating Scale,26 passivity using the Passivity in Dementia Scale,26 mood with the Dementia Mood Picture Task,26 discomfort with the Discomfort-Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type,27 pain using the Faces Legs Activity Cry Consolability Behavioural Scale,26 functional status using the Multi-Dimensional Assessment Instrument23 and quality of life with the EuroQol5D.33 Three studies individually assessed one of the following medications: antidepressants,29 psychoactives,34 antipsychotics31 and affective assessments,26 using visual analogue scales.27 Studies also assessed resident engagement23 26 and staff acceptability outcomes.30 One study26 assessed time on task and engagement (ie, resident engagement outcomes) using judge-rated videotapes. One study assessed a therapist’s rating of progress, nurses’ ratings of interventions’ acceptability through an interview, and nurses’ rating of change in target behaviours’ frequency and severity30 (ie, perceived treatment efficacy outcomes) using a goal attainment scaling approach and four-point scale, respectively. One study31 assessed staff stress-related symptoms, job experience and job satisfaction using the General Health Questionnaire, Questionnaire about Experience and Assessment of Work, and Maastricht Job Satisfaction Scale for Healthcare respectively.

Metrics that were used for management of diabetes mellitus included incidence of hyperglycaemia/hypoglycaemia through chart reviews,25 use of pharmacotherapy (eg, metformin, sulfonylureas and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors),25 preventive screenings for kidney disease25 and number of completed assessment sheets.32

Metrics that were used for management of heart failure included use of pharmacotherapy (ACE inhibitors),28 using a chart review or electronic pharmacy records review, and collecting clinical information (eg, standardised nursing assessments,28 physical assessments28 and electrocardiograms.28

Study efficacy

Of the 13 studies included, only seven studies showed at least one significant outcome change (table 3). Among studies that evaluated interventions for residents with dementia, Chapman and colleagues24 looked at the effectiveness of advanced illness care teams for NH residents with advanced dementia. They reported a significant decrease in the treatment group’s physically non-aggressive behaviours (F=4.22, p<0.05) but no change in their pain or depression scores. Similarly, Opie and colleagues30 introduced individually tailored psychosocial, nursing and medical interventions to NH residents and found significant reductions in residents’ restlessness (p<0.05), verbal disruptions (p<0.005) and inappropriate behaviours (p<0.05) after the intervention. Zwijsen and colleagues34 noted that odds of being prescribed psychoactive drugs were significantly lower after the introduction of a care programme including a multidisciplinary assessment and management of challenging behaviours (p<0.05). Brodaty and colleagues29 conducted an RCT with the intervention consisting of psychogeriatric case management. Overall, this intervention had a significant improvement on depression (F=32.7, df=1,61, p<0.001) and psychosis (F=10.7, df=1,45, p<0.01). Carpenter and colleagues23 noted a decrease in depression scores after their Restore, Empower and Mobilise psychotherapy intervention. Kovach and colleagues27 noted significant decreases in discomfort among residents with dementia (p<0.001) but no effect on behavioural symptoms. Kolanowski and colleagues26 noted a significant difference in positive affect (p<0.001) for residents receiving a combination of activities (artistic activities matched to style of interest) as compared with those receiving regular artistic activities. Van de Ven and colleagues33 found that their intervention had no effect on agitation scores but reported more neuropsychiatric symptoms were reported in the intervention group than in groups who received usual care (p=0.02). Vida and colleagues’31 work on discontinuation or dose reduction for antipsychotics found 21.7% discontinuations, 15.2% reductions and 15.2% unsuccessful discontinuations or dose reductions. Pieper and colleagues35 found significant improvements in the rates of agitation and depression of residents with advanced dementia following a multidisciplinary training programme.

Table 3.

Evaluation of outcomes

| Chronic disease | Outcomes | Number of studies demonstrating efficacy |

| Dementia | Agitation | 4 |

| Resident engagement | 3 | |

| Depression | 1 | |

| Discontinued antipsychotics | 1 | |

| Functional status | 1 | |

| Pain/discomfort | 1 | |

| Time on task | 1 | |

| Affect | 1 | |

| Nursing assessments | 1 | |

| Quality of life | 0 | |

| Neuropsychiatric symptoms | 0 | |

| Diabetes | Insulin dose | 1 |

| Physician assessments | 1 | |

| Preventative screening | 1 | |

| Hypoglycaemia | 0 | |

| Pharmacotherapy | 0 | |

| Congestive heart failure | Availability of echocardiogram | 1 |

| Pharmacotherapy | 1 | |

| Nursing assessments | 1 | |

| Immunisation rates | 1 | |

| Education | 1 |

Day and colleagues25 assessed an intervention for managing diabetes mellitus and noted a decrease in the use of sliding scale insulin orders (p=0.004) and a significant decrease in hypoglycaemia incidence (p=0.018). Williams and Curtis32 found that assessment sheets were completed for 57% of residents with diabetes mellitus. Lastly, Martinen and Freundl28 found that measuring the effect of a heart failure management intervention on staff outcomes found increased (100%) nursing assessments (weighing resident with heart failures) and resident education, and 50% improved, appropriate use of ACE-inhibitors.

Studies are fully described in online supplementary appendix C.

bmjopen-2019-032316supp003.pdf (239.1KB, pdf)

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to identify which chronic diseases have been the subject of intervention studies in NHs, what contextual factors are accounted for in interventions for CDM in the NH setting and what gaps exist in the study of CDM in NHs. The review identified 13 studies which developed and tested CDM interventions using a component of the CCM10 in NH settings; which may suggest that the importance of incorporating the CCM10 in CDM in NHs is undervalued. Additionally, as the CCM10 is a general model which is not specific to NHs, there may be additional contextual factors which are important for care delivery which were not addressed in the included studies of this review. A lack of robust intervention research in the CDM field is, unfortunately, not uncommon. Reviews36 37 examining feasibility and acceptability of CDM interventions in primary care identified persistent concerns with studies’ methodological rigour and ongoing sustainability. Among the included studies, the majority were published in the last 10 years within the USA. Research was heavily focused on management of dementia and the most commonly included CCM10 components were multidisciplinary care, evidence-based care, coordinated care and clinical information systems. Studies generally used case management, provider education, and nursing assessments within their interventions. A significant change in outcomes was only observed in approximately half of the studies, which is a testament to the challenge in CDM in NHs.

Interestingly, there appeared to be no studies identified using the CCM10 for managing other common chronic diseases in NHs such as cancer or chronic respiratory disease (eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)). One possible reason for this could be that most of the current NH research focuses on quality of life and the person’s lived experiences and, traditionally, the management of these diseases tends to be medically focused. To this point, there appears to be a gap in research on how CDM informed by the CCM10 may become more meaningful to older adults approaching the end of their lives by evaluating both improvements in physical functionality and quality of life outcomes. Likewise, we found in our review that for traditionally medically managed chronic diseases, such as heart failure and diabetes mellitus, outcomes tended to exclude patient perceptions and experiences (such as quality of life, perceived burden of polypharmacy or additional assessments). Including both objective and subjective outcomes which are important to residents in NHs may be a more reasonable approach.

Generally, study interventions were complex and included multidisciplinary care teams or an evidence-based approach. These results were gratifying in that multidisciplinary care teams are important to appropriately care for NH populations with multiple comorbidities and that evidence-based guidelines were used to inform care planning. Some of these guidelines for specific diseases have started to address the NH population (eg, 2018 Hypertension Canada Guidelines for Adults and Children, 2017 Comprehensive Update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Heart Failure)14 38 in terms of treatment targets, community resources and self-management support. However, it should be noted that only one study included a patient self-management component.28 Furthermore, interventions were generally not patient driven. One possible explanation for this could be related to the fact that most studies were targeting residents with late-stage dementia, limiting the resident’s ability to self-manage. However, it would be interesting to explore if disease management strategies could be co-led by residents and families. This would certainly be in line with a person-centred approach and may be more impactful on residents’ quality of life.

Additionally, only one33 of the identified studies lasted more than 1 year. None of the studies reported information on costs, availability of staff or other issues related to sustainability, all important components for a future CDM model designed for NH. Furthermore, although many of the metrics collected were evidence based, there was little comment as to integrating these assessments into everyday practice, further questioning the sustainability of some of these interventions. Overall, the quality of the studies is limited.

Some limitations of this review need to be stated. First, it is important to note that no cross-reference citations took place and that no additional references were reviewed due to time constraints. As well, a limitation of this study is that we used Wagner’s CCM model to select as well as analyse the studies. This might have potentially limited our interpretations of the study. A systematic review could further explore the quality of these studies.

Conclusion and implications

This review identified 13 interventions studies which used a component of the CCM10 to improve CDM for residents living in NHs. Research was heavily focused on management of dementia. The most commonly included CCM10 components were multidisciplinary care, evidence-based care, coordinated care and clinical information systems. Studies generally used case management, provider education and nursing assessments within their interventions. A significant change in outcomes was only observed in approximately half of the studies, which is a testament to the challenge in CDM in NHs. Future research may address understudied, common chronic diseases (such as COPD and cancer), include both subjective and objective outcomes which are meaningful to older adults approaching the end of their lives, and incorporate interventions which empower residents in NHs to maximise control over the management of their own health as much as possible.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Study concept and design: VB, GH and APC. Acquisition of data: MD, LEC, KJ, LST, MH, VB and GH. Analysis and interpretation of data: VB, GH, APC, LEC, MD, LST, MH and KJ. Drafting of the manuscript: VB and LEC. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: VB, GH, APC, LEC, LST, MH and KJ.

Funding: This work was supported by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care’s 2017-2020 Health System Research Fund (HSRF; Grant #255). VB receives salary support from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Industrial Council of Canada (NSERC) through the Industrial Research Chair for Colleges Program, supported by Schlegel Villages and the Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging. GH receives salary support from the University of Waterloo and Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging. APC receives salary support from McMaster University and the Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) About chronic diseases [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm [Accessed 2 Dec 2019].

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO) Health statistics and information systems: projections of mortality and causes of death, 2015 and 2030 [Internet]. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization. Available: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/projections2015_2030/en/ [Accessed 26 Feb 2019].

- 3. Vinton DT, Capp R, Rooks SP, et al. Frequent users of US emergency departments: characteristics and opportunities for intervention. Emerg Med J 2014;31:526–32. 10.1136/emermed-2013-202407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lehnert T, Heider D, Leicht H, et al. Review: health care utilization and costs of elderly persons with multiple chronic conditions. Med Care Res Rev 2011;68:387–420. 10.1177/1077558711399580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Canadian Institute for Health Information Dementia in long-term care, 2019. Available: https://www.cihi.ca/en/dementia-in-canada/dementia-across-the-health-system/dementia-in-long-term-care#top [Accessed 30 Sep 2019].

- 6. Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2269–76. 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clarke JL, Bourn S, Skoufalos A, et al. An innovative approach to health care delivery for patients with chronic conditions. Popul Health Manag 2017;20:23–30. 10.1089/pop.2016.0076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO) Rehabilitation, complex and long-term care. Available: https://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/vision-docs/RNAO-Vision-Rehab-Complex-and-Long-Term-Care.pdf [Accessed 26 Feb 2019].

- 9. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q 1996;74:511–44. 10.2307/3350391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wagner EH, Davis C, Schaefer J, et al. A survey of leading chronic disease management programs: are they consistent with the literature? Manag Care Q 1999;7:56–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scott IA. Chronic disease management: a primer for physicians. Intern Med J 2008;38:427–37. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01524.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zwar N, Harris M, Griffiths R, et al. A systematic review of chronic disease management. Available: http://files.aphcri.anu.edu.au/research/final_25_zwar_pdf_85791.pdf [Accessed 26 Feb 2019].

- 13. Baptista DR, Wiens A, Pontarolo R, et al. The chronic care model for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2016;8:1–7. 10.1186/s13098-015-0119-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ezekowitz JA, O’Meara E, McDonald MA, et al. Comprehensive update of the Canadian cardiovascular society guidelines for the management of heart failure. Can J Cardiol 2017;2017:1342–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, et al. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Syn Meth 2014;5:371–85. 10.1002/jrsm.1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reynolds R, Dennis S, Hasan I, et al. A systematic review of chronic disease management interventions in primary care. BMC Fam Pract 2018;19:1–13. 10.1186/s12875-017-0692-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:1–10. 10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:1–9. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci 2010;5:1–9. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cochrane Qualitative & Implementation Methods Group. [Internet]. Available: http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance [Accessed Oct 2019].

- 22. Boyatzis R. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc, 1998: 1–200. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carpenter B, Ruckdeschel K, Ruckdeschel H, et al. R-E-M psychotherapy: a manualized approach for long-term care residents with depression and dementia. Clin Gerontol 2002;25:25–49. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chapman DG, Toseland RW. Effectiveness of advanced illness care teams for nursing home residents with dementia. Soc Work 2007;52:321–9. 10.1093/sw/52.4.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Day C, Kimble S, Cheng A. Improving outcomes through a coordinated diabetes disease management model. Ann Longterm Care 2014;22:38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kolanowski AM, Litaker M, Buettner L. Efficacy of theory-based activities for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Nurs Res 2005;54:219–28. 10.1097/00006199-200507000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kovach CR, Logan BR, Noonan PE, et al. Effects of the serial trial intervention on discomfort and behavior of nursing home residents with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2006;21:147–55. 10.1177/1533317506288949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martinen M, Freundl M. Managing congestive heart failure in long-term care: development of an interdisciplinary protocol. J Gerontol Nurs 2004;30:5–9. 10.3928/0098-9134-20041201-05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brodaty H, Draper BM, Millar J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of different models of care for nursing home residents with dementia complicated by depression or psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:63–72. 10.4088/JCP.v64n0113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Opie J, Doyle C, O'Connor DW. Challenging behaviours in nursing home residents with dementia: a randomized controlled trial of multidisciplinary interventions. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;17:6–13. 10.1002/gps.493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vida S, Monette J, Wilchesky M, et al. A long-term care center interdisciplinary education program for antipsychotic use in dementia: program update five years later. Int Psychogeriatr 2012;24:599–605. 10.1017/S1041610211002225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Williams E, Curtis A. Implementation of a diabetes management flow sheet in a long-term care setting. Can J Diabetes 2015;39:273–7. 10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van de Ven G, Draskovic I, Adang EMM, et al. Effects of dementia-care mapping on residents and staff of care homes: a pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 2013;8:1–7. 10.1371/journal.pone.0067325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zwijsen SA, Smalbrugge M, Eefsting JA, et al. Coming to grips with challenging behavior: a cluster randomized controlled trial on the effects of a multidisciplinary care program for challenging behavior in dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:531.e1–531.e10. 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pieper MJC, Francke AL, van der Steen JT, et al. Effects of a stepwise multidisciplinary intervention for challenging behavior in advanced dementia: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:261–9. 10.1111/jgs.13868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stephen C, McInnes S, Halcomb E. The feasibility and acceptability of nurse-led chronic disease management interventions in primary care: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs 2018;74:279–88. 10.1111/jan.13450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yeoh EK, Wong MCS, Wong ELY, et al. Benefits and limitations of implementing chronic care model (Ccm) in primary care programs: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol 2018;258:279–88. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.11.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nerenberg KA, Zarnke KB, Leung AA, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2018 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults and children. Can J Cardiol 2018;34:506–25. 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-032316supp001.pdf (77.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-032316supp002.pdf (90.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-032316supp003.pdf (239.1KB, pdf)