Abstract

Objectives

Drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) is a growing concern in many low-income and middle-income countries. Facing rising numbers of DR-TB patients, South Africa (SA) introduced a decentralised model of care for DR-TB in 2011. We aimed to document the introduction and implementation of the new models of care for patients with DR-TB in four provinces (Northern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape and Gauteng) in 2015 using mixed methods, including interviews, register reviews and clinical audits. This paper reports on the qualitative component of the study.

Design

This is a qualitative interview study.

Setting

Data were collected in 22 decentralised DR-TB sites, primary healthcare facilities and district hospitals and one provincial central DR-TB hospital.

Participants

58 healthcare workers (HCWs), facility staff and provincial and district TB coordinators were included in qualitative interviews.

Results

HCWs felt that the introduction of DR-TB care in their facility came with little warning or engagement, creating fear and anxiety. They expressed a need for support from the district and province to guide them through the changes but this support was often lacking. In addition, many respondents expressed feeling isolated and not supported by other healthcare providers which they feel impacts on the quality of the care they provide.

Conclusion

Introduction of a new service such as DR-TB care can be difficult and does not always result in the intended outcomes. Improved engagement with front-line providers and addressing the fear and anxiety that may be raised by changes in daily practices should be addressed to ensure successful implementation and prevent negative consequences that can hamper quality of care for patients. Attention should be paid to how the decentralised DR-TB unit can be supported by district management and other healthcare providers.

Keywords: tuberculosis, public health, health services administration & management, change management, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides new information about front-line healthcare workers’ (HCWs) and facility staff experiences of the introduction and implementation of new models of care for drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) patients on a decentralised level in a high-burden country.

This study was conducted in nine districts in four provinces, ensuring an adequate range of experiences from providers between provinces, as well as between rural and urban areas.

This study provides insight into the perceptions and experiences of staff within different levels of care, as well as provincial and district management.

However, as this is a qualitative study results cannot be generalised beyond the specific facilities that participated in the study.

More research is needed to obtain a holistic picture of the effects of decentralising DR-TB on HCWs and patients.

Background

Decentralisation has been a key health sector reform in most low-income and middle-income countries in the past two decades.1 Decentralising responsibility for the management and provision of healthcare to local spheres of government aims to reduce inequalities, increase access and improve services.2

Tuberculosis (TB) still affects thousands of people around the world every day. Globally in 2017, an estimated 10 million people fell ill with TB while an estimated 1.3 million died from the disease.3 In South Africa (SA), TB remains the leading cause of death and drug resistance has increasingly become a major public health threat.4 Facing rising numbers of drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) patients and poor treatment outcomes, SA began to pilot decentralised and ambulatory models of care for DR-TB patients in 2008.5 The move to pilot decentralisation and deinstitutionalisation of DR-TB care in SA followed studies in Peru and Vietnam conducted in the 1990s that showed good results for ambulatory treatment among DR-TB patients.6 7 Subsequently, the results of pilot studies in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) and the Western Cape (WC) in SA showed that decentralised care was more effective than care in a central, specialised hospital and that home-based care further increased treatment success.8–11

Following these results and a recommendation by the WHO in 2011,12 the National Department of Health (NDOH) introduced a strategy for decentralisation and deinstitutionalisation of DR-TB treatment.5 The strategy proposed ambulatory treatment for DR-TB patients in good condition and reducing the length of hospitalisation for those who require admission (deinstitutionalisation), and transferring responsibility for the care and treatment of DR-TB patients from a provincial centralised level to lower (district and local) levels of the health system (decentralisation). Decentralised management of DR-TB patients was expected to accommodate patients by treating them closer to their homes, reduce transmission by shortening time to initiation, improve treatment adherence and improve cost-effectiveness by reducing lengthy hospital stays in specialised hospitals.5 The roll-out of the new models of care started in 2011, although with different degrees of speed and coverage in the different provinces. Nonetheless, by October 2015, there were 578 initiating decentralised units, covering all 52 districts in SA.13

Implementation of a new service or system in an organisation requires significant changes at different levels of the organisation. The management of this organisational change, however, can be a difficult process and in many cases does not work out as it was intended,14 affecting the end user of the system or in the case of healthcare services the patients. Studies in Nepal, Uganda and Swaziland have looked at healthcare workers’ (HCWs) experiences of community-based drug-sensitive TB (DS-TB) programmes and reported issues with communication between different levels of the TB programme and poor coordination with other services in a community-based TB programme, as well as understaffing, lack of capacity and insufficient knowledge.15 16

While DS-TB is fairly easy to treat and has high treatment success rates, DR-TB is much more difficult to treat, has high mortality rates and its treatment has severe side effects. As such, challenges with the introduction of DR-TB care at decentralised level, as well as the consequences for patient care might differ substantially to those from decentralisation of DS-TB. No studies thus far have reported on HCWs’ experiences of the introduction and implementation of DR-TB, a more difficult to treat and deadlier disease than DS-TB, at district and local facilities and how they perceive it to affect the quality of care for patients. In order to address this gap in the literature, we interviewed HCWs and facility management of decentralised DR-TB units and primary healthcare (PHC) centres in four provinces, as well as provincial and district TB coordinators about their experiences of the introduction and implementation of DR-TB care, following from deinstitutionalisation and decentralisation, in facilities at district level, as well as how they perceive issues with the implementation to affect the care provided to patients. Issues explored included support from provincial and district management structures and the programmes coordination and integration with general healthcare facilities and their staff.

Methods

Context

In 2017, an estimated 322 000 South Africans fell ill with TB of which close to 16 000 cases were confirmed to have DR-TB.3 While SA has made great strides to increase treatment success for DS-TB to 82%, treatment success for DR-TB remains low at 55% with an average death rate of 22% and loss to follow-up of 17%.3

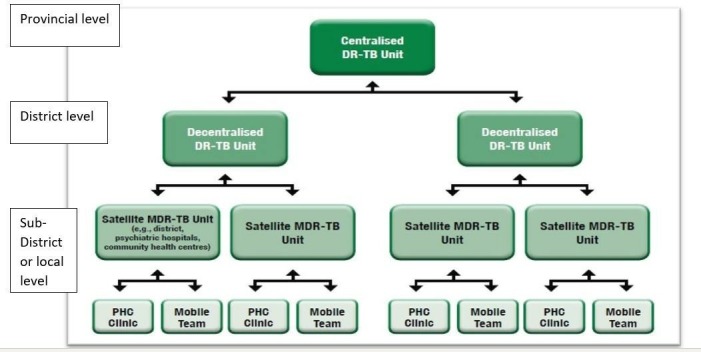

Under the decentralised model of care for DR-TB in SA, DR-TB units on district level are responsible for initiation and monitoring of treatment for DR-TB patients, while the provincial Centre of Excellence (centralised DR-TB unit) is responsible for initiation and monitoring of treatment for extensively DR-TB (XDR-TB) patients, paediatric patients and patients with complications (figure 1). The decentralisation of DR-TB services is paired with deinstitutionalisation whereby smear-negative patients in fair to good general condition no longer need to be hospitalised and can be started on ambulatory treatment. Following initiation at the decentralised unit, patients are referred to their nearest PHC facility) for daily observed treatment (DOT), daily injections, monitoring of side effects and adherence via monthly sputums and routine tests.5

Figure 1.

Units for the decentralised management of drug-resistant tuberculosis.5

While decentralised DR-TB units are mostly responsible for diagnosis and initiation on treatment, they often do not have the capacity or equipment to monitor side effects and drug resistance, perform radiography to diagnose TB or audiology to monitor hearing loss or provide transport, and therefore they need the support from PHC facilities, general district hospitals and other general healthcare services such as emergency medical services. In addition, DR-TB patients also often suffer from other conditions such as diabetes, HIV, cancer which cannot be treated at the DR-TB unit and need involvement from general healthcare services. PHC facilities and general hospitals are therefore expected to play a significant role in the decentralised model of DR-TB care.5

At the time of the interviews, implementation of the policy guidelines varied among provinces. In the WC, all PHC facilities offered treatment initiation, DOT and monitoring of treatment. In KZN, Eastern Cape and Gauteng, DR-TB patients were initiated at decentralised DR-TB units but then referred to PHC facilities for daily injections, DOT and monitoring of sputum. On a monthly or bimonthly basis, patients returned to the decentralised unit for review of their treatment based on the results of the monthly sputum monitoring at the PHC facility. The Northern Cape was providing DR-TB services mainly through an outreach model while preparing PHC facilities to start initiating patients.

Recruitment and sampling

We conducted a cross-sectional exploratory qualitative study in the Eastern Cape, KZN, Northern Cape and Gauteng. The provinces as well as facilities in each province were purposively selected with the national DR-TB director and provincial TB coordinators as they represented the variety of different models of care being implemented across the country. Each province adapted implementation according to their own needs, capacities and resources, resulting in different models and varying levels of progress with implementation. Ten decentralised units, 1 central specialised unit and 12 primary healthcare facilities were selected for data collection in these four provinces. The provincial or district TB coordinator introduced the researchers to the facility manager for the first interview, after which purposive sampling was used to recruit HCWs, based on their designation (doctors and nurses) and placement (TB focal point). The final selection of HCWs was made on the day by the researchers LV and VM in discussion with the facility manager or head nurse and depending on the availability of healthcare workers. We recognise that this process may have influenced the results. Interviews were conducted until data saturation was reached with a total of 43 HCWs, 9 operational managers, 6 provincial and district coordinators, 5 administrative staff and 2 social workers.

Data collection

Qualitative data were collected from November 2015 until April 2017 using semi-structured interview guides that were developed for each type of staff category (nurse, doctor, operational manager, provincial/district coordinator) with questions related to their knowledge and training, tasks, challenges, support and resources. Questions were open-ended and the interviewer led the interview as little as possible to make participants feel more comfortable in sharing their personal perceptions and experiences.

All interviews took place in the participants’ place of work during work hours. The rooms where interviews took place were all private and sound proofed, and respondents seemed free to express themselves. Date and time were arranged prior to the interview to accommodate the participants’ work schedule and cause as little disturbance to the patient flow and facility staff as possible. Most interviews were recorded and transcribed. Some participants however did not feel comfortable being recorded. During these interviews, notes were taken. Data were constantly reviewed by LV, VM and ML and emerging themes related to the original research question as well as new areas were taken into consideration for further interviews. Transcripts and notes were deidentified and stored on secured servers at the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC).

Validation of data was ensured by triangulation by means of a ‘thick’ description of the context, focused observation of daily practice and attendance of patient review meetings as well as staff meetings.

Researcher characteristics and reflexivity

Interviews were conducted by two researchers, LV and VM, with a master qualification in the field of social or health sciences and training in qualitative research in public health. Both researchers had no prior relationship with the selected facilities or their staff. As both researchers were introduced to the facilities by a provincial or district coordinator, they were aware of the possibility that they might be perceived as ‘sent by head office to check on facilities’. In addition, LV was aware that being white and foreign, despite long residence in SA, might be received with feelings of suspicion or resentment linked to SA’s history of apartheid and colonialisation. Both researchers ensured that enough time was spent explaining the study as well as answering any questions regarding the study or the researchers’ background to create transparency and reduce anxiety. While all but one participant were either black African or Coloured, no major differences were perceived in the type of responses in interviews conducted by LV, a white foreign female English-speaking researcher, or VM, a black South African female Xhosa-speaking researcher. From the interviews it became clear that participants felt free to express also negative views of the process, and no power differentials were evident.

Data analysis

Transcripts and notes were coded manually and analysed using thematic content analysis by LV.17 Transcripts were read and re-read to allow for familiarisation and to start the process of open coding. Coding was performed inductively, without following predetermined codes. Codes were grouped into clusters around similar and inter-related ideas from which several themes emerged. Preliminary analysis was performed by LV and reviewed by ML, SA and WZ-M, following which the analysis was revised.

Patient and public involvement

The national DR-TB coordinator as well as provincial TB coordinators were involved in the selection of the DR-TB facilities for the study. Patients and the general public were however not involved in the design or planning of the study.

Ethical considerations

All participants were given informed consent forms which were read together with the participant and explained in detail before forms were signed. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study, procedures involved, risks and benefits of the study and their rights as participants. The right to decline participation was emphasised, as well as an assurance given that the decision not to participate would not affect their work or relationship with superiors, colleagues and patients. Participants were given an assurance of confidentiality and strict protection of collected data.

Results

Between November 2015 and April 2017, 67 interviews were conducted with 43 HCWs, 5 administrative staff, 2 social workers, 9 operational managers and 6 provincial/district TB coordinators at 10 decentralised units, 1 central specialised unit and 12 primary healthcare facilities in four provinces in SA: Eastern Cape, KZN, Gauteng and Northern Cape. For the purpose of this article and its focus on experiences of HCWs and facility management of the introduction and implementation of DR-TB care in their facility, we excluded the interviews with administrative staff and social workers as these had a different focus. We included interviews with TB coordinators to allow for their response to the stated challenges. Two nurses were interviewed twice because of the depth and richness of their knowledge of the local context. We therefore had a total of 60 interviews in the analysis (table 1).

Table 1.

Details of interviews

| Nurse | Doctor | Facility manager/ CEO | Provincial/district TB coordinator | Total participants | Total interviews | |

| Eastern Cape | 10 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 17 | 17 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 7 |

| Gauteng | 13 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 19 | 20 |

| Northern Cape | 11 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 15 |

| Total | 36 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 58 |

Several themes emerged from the interviews related to operational challenges, introduction of DR-TB care, leadership, training, human resources, infection control and infrastructure, and finances and resources. For this manuscript, however, we focused on those related to the introduction of DR-TB care in the facility and support during the implementation, as these came up strongly in the data, and raised several implications for effective patient care.

Three main themes related to the introduction and implementation of DR-TB care in the facility emerged from the analysis:

Introduction of DR-TB care in the facility: ‘They just dropped it on us.’

Support from district and province: ‘We never hear from them.’

Inadequate coordination and integration between the DR-TB programme and other healthcare services: ‘Once we refer them back, we lose control of them.’

Introduction of DR-TB care in the facility ‘They just dropped it on us’

HCWs in all four study provinces remarked that the introduction of DR-TB care in their facility came with little warning or engagement from district or provincial levels. In most facilities, treatment and care for DR-TB patients was simply added to the workload of the TB (and/or HIV) room.

They told us like a week or towards the end of September that we will be starting in October, it was hectic. They called our acting CEO, they called her over the phone to tell her that we need to (start initiating DR-TB patients). (Nurse, decentralised unit)

Many HCWs felt that these decisions were taken over their heads, even though it affected their daily work and their own personal health, creating anxiety and tension among HCWs. Especially HCWs at PHC facilities were agitated about the manner in which decisions were made. While most HCWs at decentralised DR-TB units mentioned some previous experience with DR-TB patients, the majority of HCWs at primary healthcare level did not have this experience and expressed concern with the sudden addition of DR-TB patients to their daily routine.

As one HCW remarked:

They just dropped it on us, without no explanation, the one moment I had nothing the next moment I have eight patients. (Nurse, PHC)

TB coordinators explained that NIMDR (nurse initiation of DR-TB) training had been organised by the NDOH, as well as a readiness assessment of facilities earmarked for the initiation of DR-TB, although with the necessary complications:

The readiness assessment was actual done after some of the decentralisation processes were started, which I think it should have been the first thing before any implementation was done. (TB coordinator)

The district was trained by National. The only problem is that when training is done only a certain number of staff can attend which is then limiting. Like maybe they will say 1 candidate per facility. They started by training the managers and HAST coordinators, then nurses and doctors. (TB coordinator)

Support from district and province: ‘We never hear from them’

At a district level, the implementation of decentralisation is the responsibility of the district TB coordinator. He/she is responsible for informing, training and supporting the decentralised DR-TB units and PHC facilities that are providing DR-TB care. HCWs in the TB room particularly felt that they needed the support from the TB coordinator to guide them through the changes, to monitor that they are doing it right and to assist them with logistical and patient-related challenges. Most HCWs and facility managers, however, mentioned a lack of support from the district.

It was forced upon us. We’re afraid of initiating DR (-TB treatment) because of the side-effects. How to manage all this? We had a quick training but nobody walks you through it on the job. Then something goes wrong and people litigate against the department and the nurse is held responsible. (Nurse, PHC)

The challenges that we have with the district coordinator … She does not come to visit us. She doesn’t come to support us. She doesn’t at all. So now we end up not knowing whether we are right or we are wrong. (Nurse, decentralised unit)

While participants commended the provincial department of health for supporting the facilities with equipment such as the Kudu Wave (portable audiometer) and laptops, and providing training for DR-TB, continuous support and presence from the province also seemed to be lacking.

Provincial people come down here with a book and write down challenges but we never hear from them again. (Nurse, decentralised unit)

The lack of district support, however, seemed to be related to issues of capacity and time. In one district the post for TB coordinator could not be filled due to a moratorium on appointments.

I can’t say there’s any support from the district. There’s no TB coordinator in the district. They had one but the post is open again. You can’t expect the district manager to visit all the institutions. They were supposed to make sure that they fill the post for TB. (CEO, decentralised unit)

In two other districts, coordinators confirmed that they struggle to support the DR-TB facilities because of their workload.

It’s not only TB that I am looking at, I’m also looking at HIV, and HIV there’s a lot of changes and things that’s going on in HIV, new research is coming in, new developments is coming in, these developments need to be implemented so I think these are taking more of the time from the TB. (TB coordinator)

Inadequate coordination and integration between the DR-TB programme and general healthcare services: ‘Once we refer them back, we lose control of them’

Following initiation at the decentralised unit, patients are referred to their nearest primary healthcare facility (PHC) for DOT and treatment monitored by taking monthly sputum samples from patients. HCWs at most decentralised units experienced problems with down-referral to the surrounding PHC facilities, saying that monitoring of sputum seldom happens.

Basic things need to be available. The absence of the monthly sputums is a huge challenge. … So sometimes you sit in OPD having to review a patient with a gap of two three months of no sputum. … At the end of it all you are not doing justice to the patient because you are making decisions without the correct information. (Doctor, decentralised unit)

In addition, HCWs at decentralised units complained of the refusal of PHC facilities to stabilise DR-TB patients before transferring them to the decentralised DR-TB unit.

Patients are being referred here that are critically ill and not stabilized before transferring at the referring clinic. (Nurse, decentralised unit)

They are rushing; won’t see the renal problem, they won’t see jaundice in that patient, they won’t see hypertension and diabetes in that patient, they won’t see cancer, they won’t see anything—the lump that needs to be scanned or whatever. They would send—quickly rush that patient to us, to get rid of it. (CEO, decentralised unit)

HCWs at PHC facilities and at decentralised DR-TB units, however, painted a picture of little support and too much work for nurses in PHC facilities.

There’s too much for the clinic sisters to do. They are making it practical for themselves to make it work. The sister is doing TB, child immunization, PMTCT, ARV. There’s way too much for those sisters to cope at the clinic. How can this be resolved? More personnel. (Doctor, decentralised unit)

Difficulties with cooperation and coordination were not limited to PHC facilities. HCWs at decentralised DR-TB units spoke of serious difficulties with hospitals and other healthcare services when requesting services that they could not provide themselves but were essential to the well-being of the patient such as radiology, audiology and transport.

You can make appointments make appointments and make appointments, but transport won’t pitch because ambulance people are refusing to transport DR patients. Even with their masks on … (Nurse, PHC)

We send people to Hospital X for X-rays because we don’t have a radiographer. But the radiographers there don’t want to touch the patient because they are afraid of DR-TB. (CEO, decentralised unit)

Patients being injected with kanamycin as part of their treatment regimen need to undergo a hearing test on a monthly basis to monitor any hearing loss due to the ototoxic effect of kanamycin. Several HCWs at decentralised units, however, reported challenges accessing audiology services, resulting in patients suffering hearing loss.

It’s a problem because there is no baseline and patients tend to report at a much advanced state. … By the time they come back for the review they are completely deaf or are at a stage where it’s so advanced that it’s irreversible. (Doctor, decentralised unit)

In the experience of staff at the decentralised units, many of these difficulties arise from fear and stigma of DR-TB with service providers who have not received training for TB.

These doctors are scared of TB patients and refer them quickly. It’s a problem with staff on that side. It’s stigma of DR and TB. They dump the patient here after hours when doctors and staff are off. (Nurse, decentralised unit)

The call for more training and education is supported by several TB coordinators.

The attitude towards TB doesn’t help. If a patient is admitted in casualty at the general hospital for a broken femur. But when he is a DR patient, they will leave everything and refer the patient immediately to the TB hospital. A lot of education needs to happen. (TB coordinator)

More training is needed for everyone for example, clinics, allied worker, staff in the hospital. There’s still a lot of stigma on TB among hospital staff which makes it difficult. (TB coordinator)

One district coordinator, however, attributed the lack of support from other parts of the healthcare system to a lack of integration between district health services (DHS) and disease-specific programmes such as DR-TB.

District managers are accountable to the office of district health services (DHS), not to the programmes. We need to force that relationship so that programmes come together with DHS. (TB coordinator)

Discussion

We reported experiences from HCWs, facility management and provincial and district TB coordinators of the introduction and implementation of DR-TB care at decentralised facilities. We focused on experiences related to introduction of DR-TB care in facilities, support and coordination and integration, as these were the strongest themes in the data.

A fundamental but often overlooked difficulty in ‘change management’ is the ‘human factor’, managing the impact that change has on employees.18 Implementation often fails because it is conceptualised as a simple set of operational steps that need to be taken and does not take into account the effect that change will have on employees or the way employees attempt to cope with these changes.18 Fear of the unknown and uncertainty can become sources of resistance. People need predictability which has to do with their basic need for security.19 Many HCWs and facility managers in our study, however, felt that decisions were taken over their head even though it affected their daily work and their own personal health. Especially among HCWs in primary healthcare facilities that did not have previous experience or training in treatment of DR-TB, the introduction of DR-TB services at the facility created anxiety and tension which can result in resistance against or adaptation of the new service which in turn can lead to substandard quality of care. Several studies in SA have shown that when HCWs are not engaged with the development and implementation of a new policy, resistance can grow and affect the quality of the services they offer.1 20 21 For example, the lack of consultation with nurses whose daily practices were to be affected significantly when free healthcare was introduced resulted in nurses rationing services as a coping mechanism.21

The need for intense and prolonged engagement with those who will be providing the new service is even more essential when the new policy concerns a value laden or stigmatised condition, as for example found with the implementation of a new policy to increase access to safe abortions where HCWs outright refused to offer the service.1 Similarly, in our study, the introduction of care for DR-TB, an infectious and deadly disease that is difficult to treat, raised anxiety on both a personal level, that is the fear of infection, and on a professional level, that is the frustration of an increased workload. Front-line providers need to be a part of the process and they need to be heard, since people are more likely to accept the forthcoming change if they know what to expect.22 More engagement and addressing the fear that is evoked not only by the disease but also by the sudden change in daily practice is therefore critical to ensure successful implementation of the new policy and prevent unintended negative consequences that can hamper quality of care for patients.

In addition, HCWs in our study also experienced isolation and a lack of support from other healthcare providers. The decentralisation of DR-TB has established a vertical programme with targeted delivery, and its own coordination, financing, information mechanisms and lines of accountability. This vertical programme however has to function in an already established general DHS which is not accountable to the DR-TB programme. As a result, as shown in our study, HCWs in the DR-TB programme found themselves in a position where they depended on the other healthcare services to provide effective care to their patients but in many cases they were at the mercy of these services and their willingness to assist. Several studies have reported on similar problems with referrals between different facilities during centralised DR-TB care, resulting in a lack of continuity of care, and negative consequences for patients.23–25 While decentralisation inherently requires strong coordination and effective referral between facilities to ensure continuum of care, our study shows that many of these problems with referral continued and might have worsened post-decentralisation.

While much has been said and done about the integration of the HIV programme with the TB programme,26 27 and within the DHS,28 29 far less attention has been given to the integration of the DR-TB programme within the DHS. Insufficient integration of DR-TB services into existing TB, PHC and other general healthcare services and the resulting experiences of isolation and a lack of support from these services have been previously shown to affect treatment outcomes.30 More research is needed to assess coordination and integration of DR-TB care, its effect on patient care and mechanisms to improve it.

Like all qualitative studies, these results cannot be generalised beyond the specific facilities that participated in the study though theoretical transferability to similar contexts and issues is possible. Our study mainly focused on decentralised DR-TB units and less on PHC and other general healthcare facilities. As a consequence, our results show the point of view of HCWs in decentralised units and to a minimal degree have incorporated experiences from other healthcare facilities. In no way, however, does this study intend to cast blame on PHC and general healthcare facilities but recommends more research to obtain a holistic picture of the effects of decentralising DR-TB. In addition, we recognise that the sampling process, that is the selection of provinces and facilities in agreement with national and provincial TB coordinators, may have influenced the results.

Conclusion

Front-line HCWs are key in the implementation of a new policy such as the decentralisation and deinstitutionalisation of DR-TB in SA. While this new model of care affects their daily work and personal health, HCWs in our study reported a lack of engagement when DR-TB was introduced in the facility, and feelings of isolation and a lack of support from the district and provincial health system as well as general healthcare services such as audiology, radiology and patient transport on which they rely.

Improved engagement with and support for front-line providers, and addressing the fear that is evoked not only by the disease but also by the sudden change in daily practice, are critical to ensure successful implementation of the new model of care and prevent unintended negative consequences that can hamper quality of care for patients. In addition, improved coordination and integration of the DR-TB programme into the district health system can increase the levels of support needed by HCWs in the care of DR-TB patients and thereby improve the quality of care in a decentralised model of care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Vuyelwa Mehlomakulu for her contribution in conducting some of the interviews for the study.

Footnotes

Twitter: @wzembe

Contributors: ML conceptualised and was the principal investigator on the study 'Monitoring the roll-out of new models of care for MDR-TB patients in South Africa' which provided the data for this manuscript. LV and Ms Vuyelwa Mehlomakulu conducted interviews and collected data for aforementioned study. LV analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. WZ-M and SA, together with ML, reviewed and edited the manuscript multiple times and provided guidance to LV.

Funding: The work was funded by the Medical Research Council of South Africa, the National Research Foundation and a United Way Worldwide grant made possible by the Lilly Foundation on behalf of the Lilly MDR-TB Partnership. The funders had no role in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. All researchers were independent of funders and sponsors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the South African Medical Research Council (EC023-8-2015).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available. No data are available.

Author note: The terms coloured and black African were apartheid classifications of people in South Africa and continue to be used in South Africa as official and acceptable terms as they frame the historical and lived experience of South Africans.

References

- 1. McIntyre D, Klugman B. The human face of decentralisation and integration of health services: experience from South Africa. Reprod Health Matters 2003;11:108–19. 10.1016/S0968-8080(03)02166-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McCoy D. Restructuring health services of South Africa: the District Health System : Khosa MM, Infrastructure mandates for change 1994-1999. Pretoria: HSRC, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Global tuberculosis report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Statistics South Africa Mortality and causes of death in South Africa, 2016: findings from death notification. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5. South African Department of Health Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis: a policy framework on decentralised and deinstitutionalised managment for South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ward HA, Marciniuk DD, Hoeppner VH, et al. Treatment outcome of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among Vietnamese immigrants. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2005;9:164–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mitnick C, Bayona J, Palacios E, et al. Community-based therapy for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Lima, Peru. N Engl J Med 2003;348:119–28. 10.1056/NEJMoa022928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brust JCM, Shah NS, Scott M, et al. Integrated, home-based treatment for MDR-TB and HIV in rural South Africa: an alternate model of care. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2012;16:998–1004. 10.5588/ijtld.11.0713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Loveday M, Wallengren K, Voce A, et al. Comparing early treatment outcomes of MDR-TB in decentralised and centralised settings in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2012;16:209–15. 10.5588/ijtld.11.0401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cox H, Hughes J, Daniels J, et al. Community-based treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis in Khayelitsha, South Africa. int j tuberc lung dis 2014;18:441–8. 10.5588/ijtld.13.0742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heller T, Lessells RJ, Wallrauch CG, et al. Community-based treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2010;14:420–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Falzon D, Jaramillo E, Schünemann HJ, et al. WHO guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis: 2011 update. Eur Respir J 2011;38:516–28. 10.1183/09031936.00073611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. NDOH/WHO Towards universal health coverage: report of the evaluation of South Africa drug resistant TB programme and its implementation of the policy framework on decentralised and Deinstitutionalised management of multidrug resistant TB. Pretoria, South Africa: NDOH, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kotter JP. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail Harvard Business Review; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nansera D, Bajunirwe F, Kabakyenga J, et al. Opportunities and barriers for implementation of integrated TB and HIV care in lower level health units: experiences from a rural Western Ugandan district. Afr Health Sci 2010;10:312–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Escott S, Walley J. Listening to those on the frontline: lessons for community-based tuberculosis programmes from a qualitative study in Swaziland. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:1701–10. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 2004;24:105–12. 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Van Tonder CL. Organisational change—theory and practice. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik Uitgewers, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev 1943;50:370–96. 10.1037/h0054346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scott V, Mathews V, Gilson L. Constraints to implementing an equity-promoting staff allocation policy: understanding mid-level managers' and nurses' perspectives affecting implementation in South Africa. Health Policy Plan 2012;27:138–46. 10.1093/heapol/czr020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walker L, Gilson L. 'We are bitter but we are satisfied': nurses as street-level bureaucrats in South Africa. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1251–61. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gotsill G, Meryl N. From resistance to acceptance: how to implement change management Training and development; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Edginton ME, Wong ML, Phofa R, et al. Tuberculosis at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital: numbers of patients diagnosed and outcomes of referrals to district clinics. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2005;9:398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dudley L, Mukinda F, Dyers R, et al. Mind the gap! risk factors for poor continuity of care of TB patients discharged from a hospital in the Western Cape, South Africa. PLoS One 2018;13:e0190258 10.1371/journal.pone.0190258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loveday M, Thomson L, Chopra M, et al. A health systems assessment of the KwaZulu-Natal tuberculosis programme in the context of increasing drug resistance. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008;12:1042–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coker R, Balen J, Mounier-Jack S, et al. A conceptual and analytical approach to comparative analysis of country case studies: HIV and TB control programmes and health systems integration. Health Policy Plan 2010;25 Suppl 1:i21–31. 10.1093/heapol/czq054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Loveday M, Zweigenthal V. TB and HIV integration: obstacles and possible solutions to implementation in South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2011;16:431–8. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02721.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kawonga M, Fonn S, Blaauw D. Administrative integration of vertical HIV monitoring and evaluation into health systems: a case study from South Africa. Glob Health Action 2013;6:19252 10.3402/gha.v6i0.19252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shigayeva A, Atun R, McKee M, et al. Health systems, communicable diseases and integration. Health Policy Plan 2010;25 Suppl 1:i4–20. 10.1093/heapol/czq060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Loveday M, Padayatchi N, Wallengren K, et al. Association between health systems performance and treatment outcomes in patients co-infected with MDR-TB and HIV in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: implications for TB programmes. PLoS One 2014;9:e94016 10.1371/journal.pone.0094016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.