Abstract

Introduction

Because of the lack of prehospital protocols to rule out a non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS), patients with chest pain are often transferred to the emergency department (ED) for thorough evaluation. However, in low-risk patients, an ACS is rarely found, resulting in unnecessary healthcare consumption. Using the HEART (History, ECG, Age, Risk factors and Troponin) score, low-risk patients are easily identified. When a point-of-care (POC) troponin measurement is included in the HEART score, an ACS can adequately be ruled out in low-risk patients in the prehospital setting. However, it remains unclear whether a prehospital rule-out strategy using the HEART score and a POC troponin measurement in patients with suspected NSTE-ACS is cost-effective.

Methods and analysis

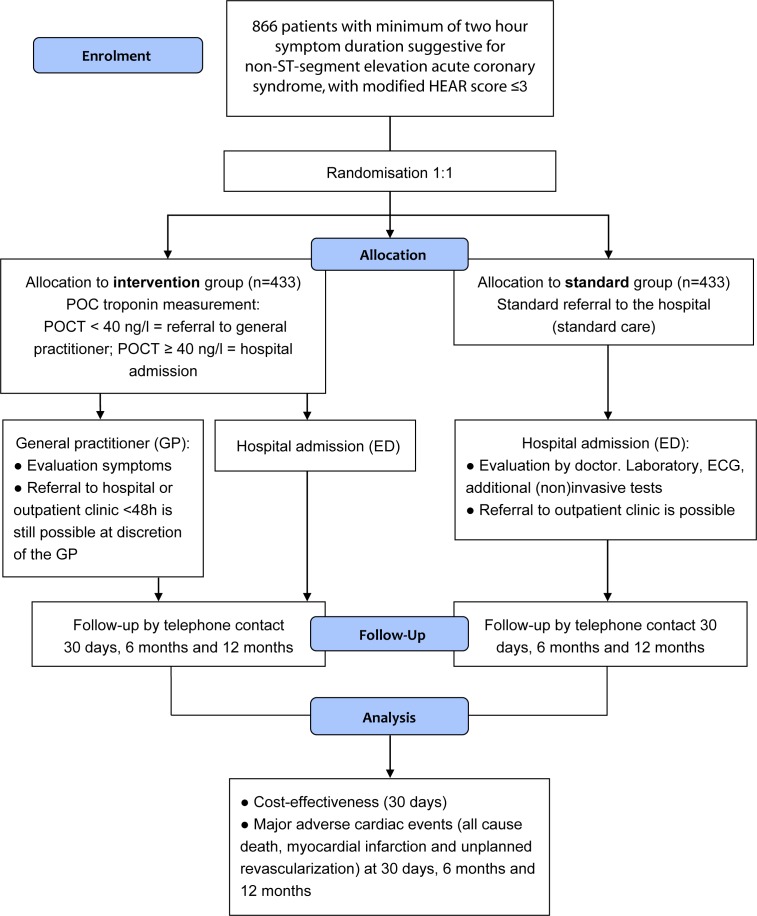

The ARTICA trial is a randomised trial in which the primary objective is to investigate the cost-effectiveness after 30 days of an early rule-out strategy for low-risk patients suspected of a NSTE-ACS, using a modified HEART score including a POC troponin T measurement. Patients are included by ambulance paramedics and 1:1 randomised for (1) presentation at the ED (control group) or (2) POC troponin T measurement (intervention group) and transfer of the care to the general practitioner in case of a low troponin T value. In total, 866 patients will be included. Follow-up will be performed after 30 days, 6 months and 12 months.

Ethics and dissemination

This trial has been accepted by the Medical Research Ethics Committee region Arnhem-Nijmegen. The results of this trial will be disseminated in one main paper and in additional papers with subgroup analyses.

Trial registration number

Netherlands Trial Register (NL7148).

Keywords: acute coronary syndrome, pre-hospital, ambulance, point-of-care troponin, modified HEART score, cost-effectiveness

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The ARTICA trial is the first randomised trial with a primary focus on cost-effectiveness of a prehospital rule-out strategy for low-risk patients suspected of an acute coronary syndrome.

When randomised for point-of-care troponin T measurement, the ambulance paramedics can rule out an acute coronary syndrome on the spot and therefore comfort the patient without having to transfer them to the emergency department.

The results of this study will provide important insights in the effects of ruling out an acute coronary syndrome without transfer to the hospital.

In order to minimise the chance of miscalculation of the HEART (History, ECG, Age, Risk factors and Troponin) score, the ambulance paramedics have to register every component of the HEART score digitally before inclusion in the trial.

The point-of-care troponin T measurement used in this trial is less sensitive than the high-sensitive troponin T measurements in the hospital laboratory, but when combined with the other components of the HEART score, the sensitivity of this modified HEART score is still high.

Introduction

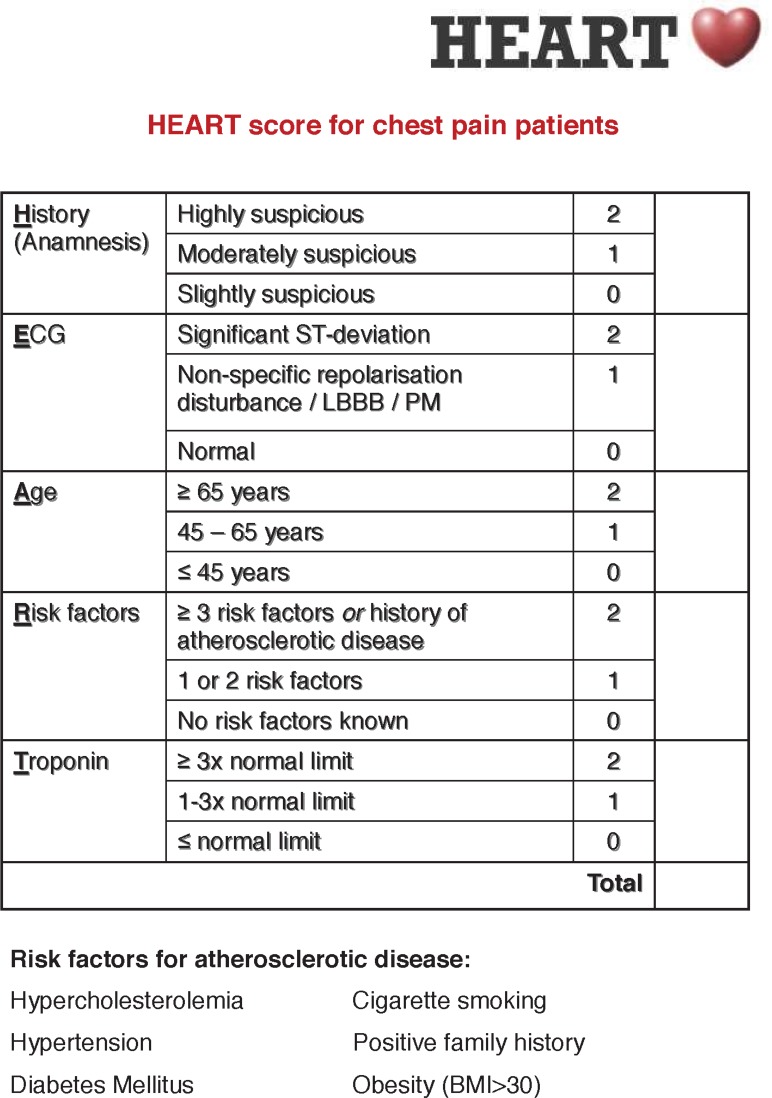

Acute chest pain poses a daily challenge for general practitioners and ambulance paramedics. Since ischaemic heart disease is the single most common cause of death worldwide, early risk stratification is crucial.1 The diagnostic foundation when an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is suspected, is a combination of a 12-lead ECG, clinical evaluation and cardiac troponin measurements.2 In patients presenting with an acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), the diagnosis is relatively straightforward after obtaining an ECG. However, in more than one-third of patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS), the ECG is normal.2 Hence, the vast majority of patients with suspected ACS is in need of further evaluation and transferred to the emergency department (ED). Chest pain is therefore one of the most chief complaints in the ED, accounting for up to over 10% of all ED visits.3–5 The number of patients visiting the ED is increasing and ED overcrowding is a global public health phenomenon, which is associated with worse patient outcomes.5–7 In addition to the increasing number of patients, healthcare costs and health expenditure per capita are also increasing, leading to a growing demand for efficiency.8 9 Only 10%–20% of the patients with chest pain have an ACS and in patients at low risk for ACS, a NSTE-ACS is rarely found.10–12 Still, these ED visits often include echocardiography, additional non-invasive ischaemia detection and prolonged in-hospital stay.10 13–15 These empirical strategies are costly, while low-risk patients are not likely to benefit from additional testing.10 15 16 A simple tool for risk stratification of patients with chest pain is the HEART (History, ECG, Age, Risk factors, Troponin) score (figure 1), which is widely validated for use in the ED.17 18 In the HEART score, patients can be given 0 to 10 points and patients with 0 to 3 points are at low risk for having an ACS. A recent meta-analysis showed that one-third of the patients presenting with chest pain have a HEART score of 0 to 3, with a risk of 1.9% of developing short-term (30 days to 6 weeks) major adverse cardiac events (MACEs).19 The risk of MACE is even lower, 0.8%, when a modified low-risk HEART score is used, in which patients with a HEART score of 0 to 3 are only classified as low-risk patients if the troponin value is below the 99th percentile.19 Implementation of the HEART Pathway, a protocol in which early discharge from the ED without further testing is recommended in low-risk patients, resulted in significant cost savings without any MACE in the discharged patients.16 20 The HEART score has proven to have a high degree of reproducibility and an excellent interoperator agreement in both nurses and doctors.21 The FAMOUS triage study group has demonstrated that HEART score assessment by ambulance paramedics is feasible and safe.22 Moreover, ambulance paramedics can adequately assess a complete HEART score, using a point-of-care (POC) troponin T measurement.23 Thus, prehospital triage of patients suspected of a NSTE-ACS is possible. The cost-effectiveness of this prehospital strategy has not been investigated yet. Therefore, it remains unclear whether identification of low-risk patients presenting with chest pain in the pre-hospital setting and accordingly not transferring them to the ED will lead to a reduction in healthcare costs. The aim of the ARTICA trial is to assess the cost-effectiveness of rule-out of a NSTE-ACS in low-risk patients in the prehospital setting.

Figure 1.

Original HEART score, with permission of the authors. BMI, body mass index; LBBB, left bundle branch block; PM, pacemaker.

Methods and analysis

Objectives

The primary objective of the ARTICA trial is to investigate the cost-effectiveness, assessed by healthcare costs after 30 days, of a prehospital rule-out strategy for low-risk patients suspected of a NSTE-ACS, using a modified HEART score and a POC troponin T measurement, compared with standard transfer to the ED. The secondary objective is to determine safety of this prehospital rule-out strategy, defined as the incidence of MACE.

Design and population

The ARTICA trial is a randomised, investigator-initiated, multicentre study. Patients with possible ACS are screened for eligibility by trained ambulance paramedics (figure 2). The patients are screened using the Castor Electronic Data Capture (Castor EDC) platform in which the ambulance paramedics register every aspect of the HEAR score (the HEART score without the Troponin component) and the inclusion and exclusion criteria in order to check for eligibility. The paramedics are able to send the ECG to a cardiologist digitally in case of doubt. After being informed by the ambulance professional and having provided written consent, the patients will be subjected to a digital 1:1 randomisation in Castor EDC. The standard care arm will be transferred to the ED for further evaluation, as is current practice in The Netherlands. The intervention arm will undergo a POC troponin T measurement. If the POC troponin T is negative (<40 ng/L), the care for the patient will be transferred to the general practitioner. The general practitioner will further evaluate the symptoms with focus on other non-cardiac causes of the chest pain. If the POC troponin T is elevated (≥40 ng/L), the patient will be transferred to the ED, even if the total HEART score is less than or equal to 3. In order to ensure the safety of this trial, a Data Safety and Monitoring Board has been assigned. Furthermore, the study will be independently monitored by the Radboudumc technology centre for clinical studies according to Good Clinical Practice.

Figure 2.

ARTICA trial flow chart. ED, emergency department; GP, general practitioner; HEAR score, History, ECG, Age, Risk factors score; POC, point of care; POCT, point-of-care troponin.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients are eligible if they are 18 years or older, are suspected of a NSTE-ACS, have a symptom duration of at least 2 hours and have a modified HEAR score of ≤3. Patients are not eligible if they are suspected of another diagnosis requiring evaluation at the ED or if they are unable to be fully informed about the trial, for example, in case of a language barrier or cognitive impairment (table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|

|

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula; NSTE-ACS, non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

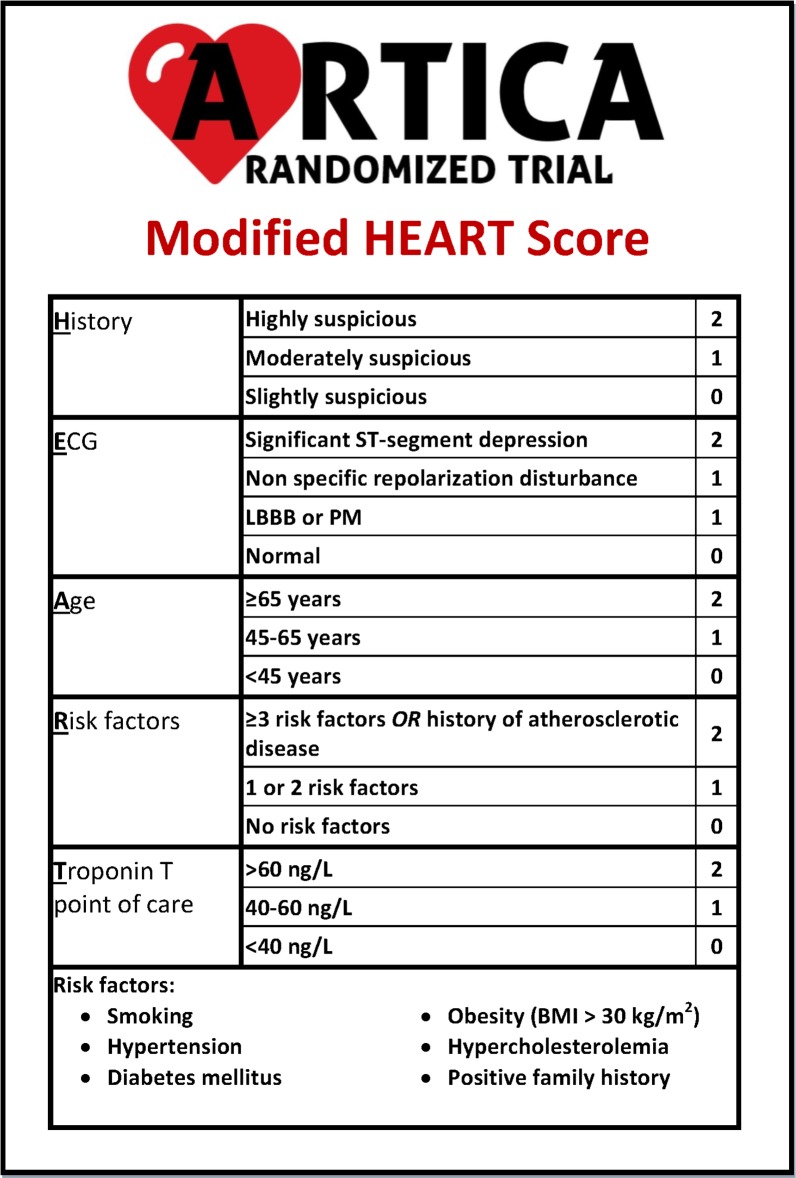

Modified HEART score

In the ARTICA trial, a modified HEART score is used. This modification is based on the inclusion of a POC troponin T measurement. Furthermore, when patients are screened for eligibility, only the H, E, A and R components of the HEART score are evaluated. The HEAR score is turned into a HEART score either by POC troponin T measurement in the ambulance or by high-sensitive troponin T measurement in the ED as part of standard care (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Modified HEART score in the ARTICA trial. BMI, body mass index; LBBB, left bundle branch block; PM, pacemaker.

POC troponin T

For the POC troponin T measurement, the Roche cobas h232 is used. The detection limit is 40–2000 ng/L. According to Roche, the measurement should be performed in a temperature of 18°C–32°C and a relative humidity of 10%–80%.24 Blood is obtained in a heparinised tube by venipuncture or venous line. Using a Roche Cardiac pipette, 150 µL of blood is applied to the POC troponin T testing strip, after inserting the testing strip in the cobas h232 POC system. After <15 min, the results are available.

Follow-up

Follow-up will be performed by phone after 30 days, 6 months and 12 months. All potential events, including hospital admissions, will be verified by review of medical record. Since the primary aim in this study is to assess the cost-effectiveness of the prehospital rule-out strategy, all healthcare resources used by the patients will be collected in both arms.

Patient involvement

During the development of the study protocol, a participant of ‘Harteraad’, a patient advisory council for patients with cardiovascular disease, was involved. This patient representative is also involved during the duration of the trial and will be consulted in case of unpredicted adverse events.

Study endpoints and cost-effectiveness analysis

The primary outcome is healthcare costs at 30 days. This economic evaluation investigates the cost-effectiveness of full implementation of a prehospital rule-out strategy compared with the standard transfer to the hospital to rule out ACS. This will be done from a societal perspective. The empirical cost-effectiveness analysis timeframe will adhere to the follow-up scheme of the secondary endpoint, being 30 days, 6 months and 12 months. Cost and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) will be measured on a per-patient basis over the relevant time path in which the (most important) differences between both arms manifest themselves. The design of the economic evaluation follows the principles of a cost-utility analysis and adheres to the most recent Dutch guidelines for performing economic evaluations in healthcare.25 For reporting, the CHEERS checklist will be used where relevant.26 Cost-effectiveness will be expressed in terms of costs per QALY gained. Quality of the health status of the patients is measured with a validated health-related quality of life (HRQoL) instrument, the EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D-5L). This HRQoL instrument will be completed by the patients and is available in a validated Dutch translation.27 The EQ-5D is a generic HRQoL instrument comprising five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. To assess productivity losses associated with chest pain, the Institute for Medical Technology Assessment Productivity Cost Questionnaire will be used.28 Uncertainty will be dealt with by one-way sensitivity analysis (deterministic) and by parametric statistics ultimately presenting cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. To ensure the quality of the economic evaluations, the Radboudumc Technology Centre Health Economics will be involved. Secondary endpoints will determine the safety of the early rule-out strategy at 30 days, 6 months and 12 months, by determining the incidence of MACE. MACE is defined as ACS, unplanned revascularisation and all-cause death. Subgroup analyses will be performed according to gender, assessment of the HEART score by paramedics or cardiologists, diabetic status and female-specific risk factors.

Sample size calculation

The cost of hospital treatment is determined by the Dutch Diagnose Behandel Combinatie (DBC) hospital reimbursement system and the DBC information system, similar to the international diagnosis related group system.29 When discharged from the ED after a negative evaluation for ACS, 50% will undergo further outpatient evaluation. This percentage and the percentages of further diagnostic testing (echocardiography and treadmill: 30%, non-invasive ischaemia detection: 10%, coronary angiography: 5%) are all based on the 2017 DBC administration in the Radboudumc. In the prehospital rule-out group, cost prices for diagnostics by the cardiologist (eg, non-invasive ischaemia detection and coronary angiography) are included, even when the probability of undergoing these tests is low. Based on the aforementioned percentages, the cost difference between both groups is estimated to be €507. For the primary outcome we assume a small effect size (0.2) and equal SD in both arms of the trial. Group sample sizes of 392 and 392 achieve 80% power to detect the difference of €507 between both groups with a significance level (alpha) of 0,05 using a two-sided two-sample t-test. To compensate for any loss of follow-up, the sample size is enlarged by 10% to a total of 866 patients. The estimated inclusion rate will be one patient per day.

Discussion

The majority of patients suspected of a NSTE-ACS is currently presented at EDs to rule out an ACS. EDs are increasingly overcrowded and ambulance services are confronted with more patient transfers. However, in low-risk patients, an ACS is rarely found.12

Cost-effectiveness

Healthcare costs are increasing because of multiple factors, such as increases in healthcare service price and intensity, population growth and ageing.8 Low-risk patients suspected of a NSTE-ACS often require an overnight stay in the hospital to undergo additional stress testing and imaging, but are not likely to benefit from additional testing.10 Even in prehospital-adjudicated low-risk patients, acute healthcare utilisation and costs are high, with limited added value.15 In the year 2018 in the Netherlands, over one-fourth of the patients who were evaluated for chest pain and eventually discharged with benign non-cardiac chest pain were admitted to the hospital for at least 1 day. The average price for these admissions was €1.355 in 2018 and is €1.410 in 2019, while it was €1.220 in 2012.30 The price for visiting the general practitioner (GP) for 5–20 min is €9.97 during working hours and €117.50 after working hours. However, it remains unclear how often the GPs will order additional tests or refer the patients to the ED or outpatient clinic, after a NSTE-ACS has been ruled out in the ambulance. Furthermore, the healthcare resource consumption in these patients represents the degree of reassurance in patients and in healthcare professionals (eg, the general practitioner).

Prehospital HEART score

Recent studies have shown the safety of identifying low-risk chest pain patients in a prehospital environment.22 23 The FAMOUS triage study group has demonstrated that identifying low-risk chest pain patients by ambulance staff using a modified HEART score is feasible and safe when using a high-sensitive troponin T measurement in the hospital laboratory.22 They have also shown that using a POC troponin T measurement to turn the HEAR score into the HEART score in the prehospital setting has important additional predictive value.31 Furthermore, they have shown that in patients suspected of NSTE-ACS, HEART score assessment using a POC troponin T measurement by ambulance paramedics is accurate in identifying low-risk patients.23

POC troponin T

The POC troponin T measured with the Roche cobas h232 yields very good analytical concordance with high sensitive troponin T.32 This POC test can be used as a bedside test with a fast turn-around time (<15 min) and was also used by the FAMOUS triage study group. The POC troponin T test has already shown to have a high predictive value for mortality in high-risk patients.33

General practitioner

In the Netherlands, the GP is a gatekeeper to hospital and specialist care. GPs offer out-of-hour services by GP co-operatives across the whole country.34 Therefore, implementation of a rule-out strategy for NSTE-ACS in the ambulance is possible, without leaving the patients to fend for themselves when they are not transferred to the ED.

Conclusion

The ARTICA trial is the first randomised trial on cost-effectiveness of an early rule-out strategy for low-risk patients suspected of an ACS, using a POC troponin measurement outside the hospital setting. The results of this study are expected to have a major impact on the healthcare organisation of patients with chest pain.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CC conceived the idea. GWAA, CC, RJvG, EC, RRJvK, PD and NvR designed the study methodology. EA designed the economical and statistical analyses. GWAA and CC drafted the manuscript. RJvG, EC, RRJvK, PD, PMvG, EA, PG, MR, OO, MERG and NvR provided critical revisions and substantial intellectual input. GWAA takes full responsibility for the data acquisition. All authors agreed with the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study is supported by ZonMw, grant number 852001942.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Medical Research Ethics Committe region Arnhem-Nijmegen. File number: 2018-4676.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Ibánez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Rev Esp Cardiol 2017;70:1082 10.1016/j.rec.2017.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet J-P, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Rev Esp Cardiol 2015;68:1125 10.1016/j.rec.2015.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mockel M, Searle J, Muller R, et al. Chief complaints in medical emergencies: do they relate to underlying disease and outcome? The Charité emergency medicine study (CHARITEM). Eur J Emerg Med 2013;20:103–8. 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328351e609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Langlo NMF, Orvik AB, Dale J, et al. The acute sick and injured patients: an overview of the emergency department patient population at a Norwegian university hospital emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med 2014;21:175–80. 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3283629c18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J, et al. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2006 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report 2008:1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sun BC, Hsia RY, Weiss RE, et al. Effect of emergency department crowding on outcomes of admitted patients. Ann Emerg Med 2013;61:605–11. e606 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rasouli HR, Esfahani AA, Nobakht M, et al. Outcomes of crowding in emergency departments; a systematic review. Arch Acad Emerg Med 2019;7:e52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dieleman JL, Squires E, Bui AL, et al. Factors associated with increases in US health care spending, 1996–2013. JAMA 2017;318:1668 10.1001/jama.2017.15927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. OECD Health at a Glance 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mahler SA, Hiestand BC, Goff DC, et al. Can the heart score safely reduce stress testing and cardiac imaging in patients at low risk for major adverse cardiac events? Crit Pathw Cardiol 2011;10:128–33. 10.1097/HPC.0b013e3182315a85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poldervaart JM, Reitsma JB, Backus BE, et al. Effect of using the heart score in patients with chest pain in the emergency department: a stepped-wedge, cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:689–97. 10.7326/M16-1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nasrallah N, Steiner H, Hasin Y. The challenge of chest pain in the emergency room: now and the future. Eur Heart J 2011;32:656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Allen BR, Simpson GG, Zeinali I, et al. Incorporation of the heart score into a low-risk chest pain pathway to safely decrease admissions. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2018;17:184–90. 10.1097/HPC.0000000000000155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Six AJ, Backus BE, Kingma A, et al. Consumption of diagnostic procedures and other cardiology care in chest pain patients after presentation at the emergency department. Neth Heart J 2012;20:499–504. 10.1007/s12471-012-0322-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Dongen DN, Ottervanger JP, Tolsma R, et al. In-hospital healthcare utilization, outcomes, and costs in pre-hospital-adjudicated low-risk chest-pain patients. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2019;17:875–82. 10.1007/s40258-019-00502-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riley RF, Miller CD, Russell GB, et al. Cost analysis of the history, ECG, age, risk factors, and initial troponin (HEART) pathway randomized control trial. Am J Emerg Med 2017;35:77–81. 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Six AJ, Backus BE, Kelder JC. Chest pain in the emergency room: value of the heart score. Neth Heart J 2008;16:191–6. 10.1007/BF03086144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Van Den Berg P, Body R. The HEART score for early rule out of acute coronary syndromes in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2018;7:111–9. 10.1177/2048872617710788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laureano-Phillips J, Robinson RD, Aryal S, et al. HEART score risk stratification of low-risk chest pain patients in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med 2019;74:187–203. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mahler SA, Riley RF, Hiestand BC, et al. The HEART pathway randomized trial: identifying emergency department patients with acute chest pain for early discharge. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2015;8:195–203. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Niven WGP, Wilson D, Goodacre S, et al. Do all HEART scores beat the same: evaluating the interoperator reliability of the heart score. Emerg Med J 2018;35:732–8. 10.1136/emermed-2018-207540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ishak M, Ali D, Fokkert MJ, et al. Fast assessment and management of chest pain patients without ST-elevation in the pre-hospital gateway (FamouS Triage): ruling out a myocardial infarction at home with the modified HEART score. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2018;7:102–10. 10.1177/2048872616687116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Dongen DN, Tolsma RT, Fokkert MJ, et al. Pre-hospital risk assessment in suspected non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: a prospective observational study. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2018:2048872618813846 10.1177/2048872618813846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Diagnostics R Roche cardiac POC troponin T method sheet, 2019. Available: http://diagnostics.roche.com

- 25. Institute NHC Guideline for economic evaluations in healthcare, 2016. Available: https://english.zorginstituutnederland.nl/publications/reports/2016/06/16/guideline-for-economic-evaluations-in-healthcare

- 26. Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. Value Health 2013;16:e1–5. 10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. M Versteegh M, M Vermeulen K, M A A Evers S, et al. Dutch tariff for the five-level version of EQ-5D. Value Health 2016;19:343–52. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bouwmans C, Krol M, Severens H, et al. The iMTA productivity cost questionnaire: a standardized instrument for measuring and valuing health-related productivity losses. Value Health 2015;18:753–8. 10.1016/j.jval.2015.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schreyögg J, Stargardt T, Tiemann O, et al. Methods to determine reimbursement rates for diagnosis related groups (DRG): a comparison of nine European countries. Health Care Manag Sci 2006;9:215–23. 10.1007/s10729-006-9040-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dutch Healthcare Authority Open data DBC information system (DIS). Available: http://www.opendisdata.nl

- 31. van Dongen DN, Fokkert MJ, Tolsma RT, et al. Value of prehospital troponin assessment in suspected non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2018;122:1610–6. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.07.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jungbauer C, Hupf J, Giannitsis E, et al. Analytical and clinical validation of a point-of-care cardiac troponin T test with an improved detection limit. Clin Lab 2017;63:633–45. 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2016.160814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rasmussen MB, Stengaard C, Sørensen JT, et al. Predictive value of routine point-of-care cardiac troponin T measurement for prehospital diagnosis and risk-stratification in patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2019;8:299–308. 10.1177/2048872617745893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Faber MJ, Burgers JS, Westert GP. A sustainable primary care system: lessons from the Netherlands. J Ambul Care Manage 2012;35:174–81. 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31823e83a4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.