Abstract

Objective

To systematically review the literature exploring the impact of isolation on hospitalised patients who are infectious: psychological and non-psychological outcomes.

Design

Systematic review with meta-analysis.

Data sources

Embase, Medline and PsycINFO were searched from inception until December 2018. Reference lists and Google Scholar were also handsearched.

Results

Twenty-six papers published from database inception to December 2018 were reviewed. A wide range of psychological and non-psychological outcomes were reported. There was a marked trend for isolated patients to exhibit higher levels of depression, the pooled standardised mean difference being 1.28 (95% CI 0.47 to 2.09) and anxiety 1.45 (95% CI 0.56 to 2.34), although both had high levels of heterogeneity, and worse outcomes for a range of care-related factors but with significant variation.

Conclusion

The review indicates that isolation to contain the risk of infection has negative consequences for segregated patients. Although strength of the evidence is weak, comprising primarily single-centre convenience samples, consistency of the effects may strengthen this conclusion. More research needs to be undertaken to examine this relationship and develop and test interventions to reduce the negative effects of isolation.

Keywords: infection control, anxiety disorders, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review covers a wide variety of the literature from a range of different clinical areas.

Data collected and the methods of collecting data on the impact of isolation is varied across studies.

These data do not show if these effects are temporary, or in most cases if they are clinically significant.

Introduction

Isolation is an established part of any infection prevention programme. Its purpose is to prevent the transmission of antibiotic-resistant pathogens, those that are highly contagious or cause serious infection.1 The effectiveness of isolation has been questioned however2–5 and it can be challenging to undertake, especially if patients’ lack of understanding of the need for segregation, boredom or distress result in uncooperative behaviour.6 A recent survey exploring the care of patients isolated for infectious conditions suggests that in clinical practice the main issues are identifying which patients need to be isolated as quickly as possible and prioritising which patients should be segregated when isolation accommodation is in short supply. Infection preventionists were aware that isolation could have negative effects on patients, such as increased risk of anxiety, depression and falls, and felt that more should be done to prevent these risks.6

Although single rooms are assumed to reduce infection risk, the evidence of ability to contain spread is equivocal7 8 and a recent study conducted in an all-single-room hospital was unable to demonstrate lower infection rates than in hospitals where most care takes place in open wards.9 This study identified the advantages and disadvantages of a single-room accommodation, whereas isolating infectious patients is generally assumed to result in adverse outcomes.10

A systematic review, reported 8 years ago, indicated higher levels of anxiety, depression, perceptions of stigmatisation and a higher incidence of falls, medication errors and other incidents that detract from patient safety among the patients who were isolated compared with those who were not.11 This review reported studies undertaken before 2010 and included patients whose experiences are unlikely to be comparable: children and adults and those isolated to reduce their own risk of infection as well as infectious patients. The review was not reported according to standards currently expected for systematic reviews12 and presents a qualitative description of patient outcomes only. A more rigorously reported and up-to-date systematic review is indicated in view of increasing concern about satisfaction with healthcare and patient safety and increasing emphasis on infection prevention as part of the global strategy to reduce risks of antimicrobial resistance.13

We undertook a systematic review of the literature to establish the effects of infection related isolation on psychological and non-psychological care-related outcomes in adults. This review is therefore more focused than previously undertaken, which also included those in protective isolation, and contains a significant body of literature published since 2010.

Method

The eligibility criteria for inclusion was that studies should compare quantitative data on psychological or non-psychological outcomes in adult patients who are in infective isolation with those not isolated. Purely symptomatic/disease progression outcomes were not included, neither were those looking at patients isolated due to immunosuppression. Studies not containing comparative data between those isolated and not isolated were also excluded. Search terms were: Patient isolation; cross infection; contact isolation; respiratory, source or contact isolation; droplet, airborne or contact precautions; cubicle; methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA); patient safety or harm; depression; anxiety; adaptation; stress; patient satisfaction; quality of life. These were searched as free-text and index terms where these existed. The information sources used were Embase, Medline and PsycINFO, which were searched from inception to December 2018. The full Medline search is shown in online supplementary file 1. Reference lists and Google Scholar were also handsearched. The characteristics of included and excluded papers are shown in online supplementary file 2. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart is given in online supplementary file 3. No protocol was published in advance.

bmjopen-2019-030371supp001.pdf (80.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030371supp002.pdf (66.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030371supp003.pdf (74.3KB, pdf)

The studies were initially screened for relevance by one author (EP), with the final stage being undertaken by two (EP and DG). Data were extracted and checked by two authors (DG and EP); where there were disagreements data were rechecked for relevance and accuracy. Where available, raw data were extracted and entered into a spreadsheet, and depending on the nature of the data either the risk ratio (RR) (where numbers of patients were given) or standardised mean difference (where other statistics were given) calculated. The results were then presented as forest plots.

Due to the variety of different settings and methods, it was deemed that the methodological and clinical heterogeneity was too broad to pool results; apart from those related to anxiety and depression, for which results were pooled using the random-effects model. This model assumes that the observed effect from each study is estimating a related but different true effect, allowing for between-study variation to be calculated in the form of heterogeneity statistics. All calculations and plots were produced using the meta and metafor packages in R.14–16 Where raw data were not provided, and the summary results are given in the text but not the forest plots. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary file 4.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Results

A total of 3879 papers were retrieved from the three databases; of which, 38 were assessed for eligibility by reading the full text. Of these, 13 studies provided data suitable for the calculation of risk ratio (RR), 5 giving psychological outcomes17–21 and 12 non-psychological19 22–32; and 8 provided data for the calculation of standardised mean differences (SMD), 6 giving psychological outcomes21 30 33–36 and 2 non-psychological.29 37 Further six studies did not provide raw data but are included in the results; three each giving psychological outcomes38–40 and non-psychological outcomes.17 41 42 Meta-analyses were possible on two outcomes: anxiety and depression from eight studies by using standardised mean difference.19–21 30 33–36 Where only RR data were given20 21 conversion to standardised mean difference was undertaken using the Campbell Collaboration calculator (https://campbellcollaboration.org/research-resources/effect-size-calculator.html).43

Where it was not possible to pool outcome data because of methodological and clinical heterogeneity, the data from studies are shown as forest plots but without meta-analysis. The forest plots contain results from the studies where sufficient data were given to calculate either the RR or standardised mean difference. A number of studies provided data on those under contact precautions, but no comparative data and so were not included.44–47

Because of the large number of non-psychological outcomes for which RR could be calculated, it was decided that a change of 20% (ie, an RR of 0.8 or less, or 1.2 or more) would be clinically significant, regardless of the statistical significance. This was a pragmatic decision, and all results are shown in online supplementary file 4. The results are shown in figures 1–6. Online supplementary file 5 contains the results that did not meet our criteria for being clinically significant. Outcomes were classified into one of three categories: those to do with quality of care; satisfaction of care; and adverse events from which median values and interquartile ranges were calculated.

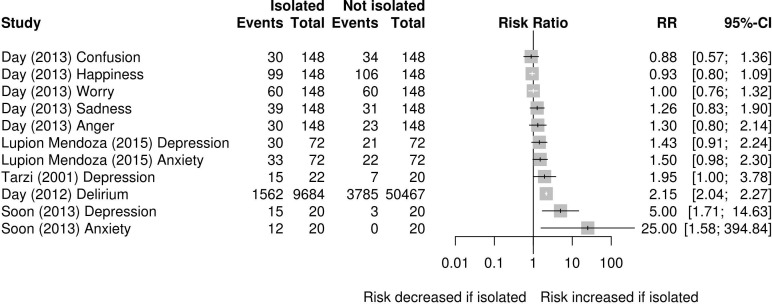

Figure 1.

Risk ratio (RR) of psychological events in those isolated versus not isolated.

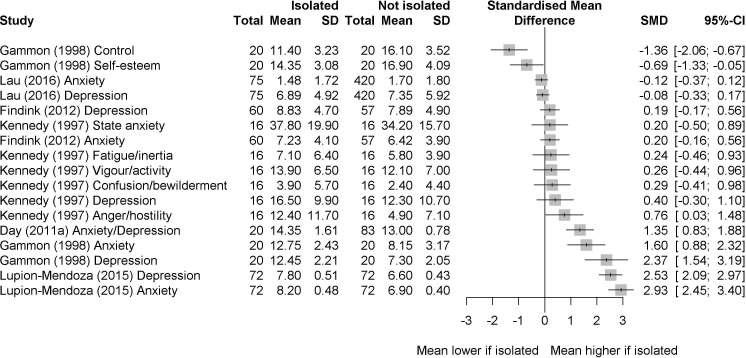

Figure 2.

Standardised mean difference of psychological scores in those isolated versus those not isolated.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of the standardised mean difference of anxiety in those isolated versus those not isolated.

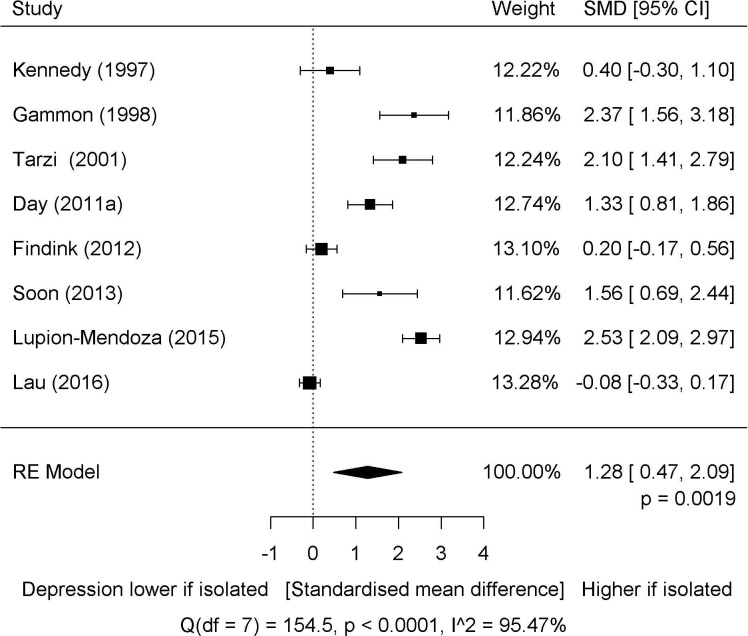

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of the standardised mean difference of depression in those isolated versus those not isolated.

Figure 5.

Risk ratio (RR) of non-psychological events in those isolated versus not isolated with an RR of ≤0.8 or ≥1.2. *Outcome was measured in rate per 100 admissions.

Figure 6.

Standardised mean difference of non-psychological scores in those isolated versus those not isolated FIM. FIM, functional independence measure.

bmjopen-2019-030371supp004.xls (61KB, xls)

bmjopen-2019-030371supp005.pdf (2.5MB, pdf)

The studies included were primarily single-centre and consisted of case–control, cross-sectional and cohort studies. The risk of bias was assessed by using the Newcastle-Ottowa scale, full details of each study and its risk of bias are in the online supplementary file 6.48 Overall, although these studies have limited generalisability, there did not appear to be significant cause for concern regarding bias within the limitations inherent in these study designs. Most studies used established or validated tools17–21 23–25 27 29 30 33–37 or clinical outcomes.22 26 28 31 32

bmjopen-2019-030371supp006.pdf (80.4KB, pdf)

The data from the comparative studies suggest that although in many cases infective isolation precautions make little difference to psychological outcomes, where it does make a difference this is primarily negative. There were significant declines in mean scores related to control and self-esteem, and in many studies increases in the mean scores for risk of anxiety and depression. However, these findings were not consistent, and some larger studies showed little or no difference between the groups for these outcomes. These are shown in figures 1 and 2, respectively.

For the eight studies reporting data on anxiety, the pooled SMD was 1.45 (95% CI 0.56 to 2.34); although within this there was significant heterogeneity (Q=168.11, df=7, p<0.0001; I2=95.84%). This was primarily caused by two studies30 34 that showed lower levels of anxiety than the remaining studies. For depression, the SMD was 1.28 (95% CI 0.47 to 2.09); again with significant heterogeneity (Q=154.5, df=7, p<0.0001; I2=95.47%), in this case the studies falling into two categories, those with lower30 34 35 and with higher depression scores among those isolated.19 20 33 36 The forest plots for these outcomes are shown in figures 3 and 4, respectively.

Studies not reporting the raw data showed that contact precautions were associated with depression OR 1.4 (95% CI 1.2 to 1.5) but not anxiety OR 0.8 (95% CI 0.7 to 1.1) in the non-ICU population.41 There was also an association with delirium OR 1.40 (95% CI 1.24 to 1.51); although this was primarily among those who were newly diagnosed as needing isolation OR 1.75 (95% CI 1.60 to 1.92, p<0.01) rather than those who had been under contact precautions for their entire stay OR 0.97 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.09, p=0.60).17 Another study showed no difference in the median values for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety or depression scores, or the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale scores.42

For non-psychological outcomes, using a difference in the risk of ±20% of an event as being a measure of clinical significance it appears there was a trend for less attention to be given to, and for more errors to occur in those who were isolated. However, again there was a wide variation between studies. Data on these outcomes are given in figures 5 and 6, and the non-clinically significant risks in the online supplementary file 5. For those outcomes associated with quality, the median RR (with positive outcomes reversed so a higher RR is associated with a worse outcome) was 0.94 (IQR 0.92–0.98), satisfaction 0.95 (IQR 0.89–1.01) and adverse events was 1.27 (0.91–2.5). The minimum and maximum RR for each category was 0.49 and 1.72; 0.3 and 8; and 0.3 and 18, respectively.

A study not giving raw data which looked at the rates of falls and pressure ulcers before and after a policy change that resulted in the discontinuation of contact precautions for patients with MRSA or vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) found that falls and pressure ulcers were more common among those with MRSA or VRE both before the change (when they were in isolation) and afterwards (when they were not). Before the change, the number of falls was 4.57 vs 2.04 per 1000 patient-days respectively (p<0.0001) and pressure ulcers 4.87 vs 1.22 per 1000 patient-days (p<0.0001). After the policy change, the same numbers were falls 4.82 vs 2.10 (p<0.0001) and pressure ulcers 4.17 vs 1.19 per 1000 patient-days (p<0.0001).39 Other studies found that staff spent less time with those on contact precautions: internal medicine interns spent less time with their isolated patients compared with non-isolated patients, the median times being 5.2 and 6.9 min, respectively (p<0.001)38; while the mean number of contacts per hour with healthcare workers was 2.1 compared with 4.2 in those not isolated (p=0.03), although the duration was longer at 4.5 min compared with 2.8 (p=0.6).40

Discussion

Current recommendations say that contact precautions should include a single room, with personal protective equipment consisting of a gown and gloves for all patient contacts or contacts with potentially contaminated environmental areas.1 This review has shown that there are a number of apparently negative aspects to contact precautions, in particular with regard to psychological effects and a reduction in the quality of some aspects of care. These data come from studies carried out in a variety of countries and different types of facilities; although there are few data from particularly vulnerable populations such as the elderly.

Although at times there are discussions as to the necessity of contact precautions for drug-resistant organisms, with some arguing that there is mixed evidence for or against their use49 another recent review has concluded that they are of great importance in the control of epidemic and endemic multidrug-resistant microorganisms.50 The ethics of using contact precautions and other forms of isolation rely on a positive assessment of the balance between the risks and benefits of this to the individual concerned and that of the broader population of patients and staff.51 However, even when this assessment is positive, it is important to ensure that any harm to the individual is minimised.

One way of balancing the various priorities is to use the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group (GRADE) Evidence to Decision Framework, which provides criteria for making recommendations at the individual, group and policy levels, and provides a number of highly patient focused criteria for doing this. In addition to the certainty of evidence and resource requirements, it also requires consideration of: the balance of desirable and undesirable effects; the impact on equity; and the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention.52 The last two of these might have very different outcomes when considered at the population and individual levels; and there is certainly evidence here that for the individual patient the balance of desirable and undesirable effects might be very different to that of the broader population.

However, within the broad population of infected or potentially infected patients, some groups might have different needs. For example a study of people isolated for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) found that while access to telephones reduced anxiety and anger; access to email, text and internet increased these.53 This was not an area investigated in any depth in these studies. Another area where information may be lacking is that of age, as older people in particular might feel sadness and loneliness more; and gender, as qualitative data suggest that women in isolation were more concerned about precautions and transmission while men were more resigned, rational and tended to cope better.54

In some countries, such as the USA, single rooms have become the standard for new hospitals and so one might expect fewer adverse effects if everyone is in a single room, this being the norm. However, it may be that a single room is necessary but not sufficient for these findings, and that it is the combination of a single room with an infection that leads to these results. Certainly it is far from clear that the long list of advantages claimed for single rooms which include reduced stress, the ability to deliver better care, and a lower probability of dietary or medication errors apply to this group of patients.55

Caring for patients in single rooms does have many challenges, but there is evidence that these can be mitigated in a general population9; however, the expanding literature on how this can be done in a general population does not necessarily apply here due to the necessity of isolation procedures which are, by design, ‘a barrier’. Therefore, patients’ needs for greater social interaction will need a solution quite different from that which might be used for a different patient population, and the benefit of choice about this which single rooms offer does not apply here.56

Although this review has quantified the extent of the problem, we have not been able to find solutions in the literature. Care might be improved through increased staff attention with more resources being allocated to these patients, although the extra cost of contact precautions is already considerable, one estimate being that it was an extra US$158.90 (95% CI US$124.90 to US$192.80) per patient day.57 Alternatively new ways of working might be developed, perhaps using technology to mitigate some of these problems. Technology might be particularly useful in reducing adverse events such as medication or clinical errors; although increasing satisfaction and some areas of quality are more likely to be achieved by increasing the availability of staff and other people. The extent to which scarce resources are allocated to this may be driven in part by the longevity of any negative effects; which current literature is not really able to clarify. To understand this, longituduinal studies are needed.

Study strengths and limitations

This review suggests that infectious isolation has a number of negative effects on patients. Because this evidence is comprised of cohort and case–control studies, a claim for a causal relationship cannot be made on this evidence, although the strong and consistent effects across the studies may increase the confidence in this relationship. There are some qualitative data, although more in-depth mixed-methods data where those reporting negative effects are questioned about them would strengthen the evidence on this. In some cases, large effect sizes were accompanied by very wide CIs, suggesting that studies were underpowered, thus studies with larger sample sizes would be useful. It would also be useful if there were more consistent methods of examining and reporting these data, particularly outside of the realms of depression and anxiety where the variety of methods makes analysis of the body of evidence difficult. We were also unable to assess whether these effects varied according to reason for isolation; or to understand if they are likely to be long-term or simply temporary phenomena.

Although these data suggest that there is a problem, there is a clear gap both in what we know about improving the experience of isolation and what can be done in practical terms to make it more tolerable for patients and their families. In particular older people who may be most vulnerable to these negative effects were under-represented in these studies; and this group is likely to represent an increasingly large proportion of those isolated.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: EP, DG and JC conceived the review, EP conducted the search, EP and DG examined the studies and extracted data, EP undertook the quantitative analysis, EP, DG and JC wrote the discussion.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention Transmission-Based precautions | basics | infection control | CDC, 2007. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/transmission-based-precautions.html [Accessed 9 Feb 2019].

- 2. Barlow GD, Knight J, McKay I, et al. An audit of the use of side- and isolation room facilities in a UK teaching hospital. J Hosp Infect 2006;62:110–2. 10.1016/j.jhin.2005.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fusco FM, Puro V, Baka A, et al. Isolation rooms for highly infectious diseases: an inventory of capabilities in European countries. J Hosp Infect 2009;73:15–23. 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Damji S, Barlow GD, Patterson L, et al. An audit of the use of isolation facilities in a UK National health service trust. J Hosp Infect 2005;60:213–7. 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wigglesworth N, Wilcox MH. Prospective evaluation of hospital isolation room capacity. J Hosp Infect 2006;63:156–61. 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gould DJ, Drey NS, Chudleigh J, et al. Isolating infectious patients: organizational, clinical, and ethical issues. Am J Infect Control 2018;46:e65–9. 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dettenkofer M, Wenzler S, Amthor S, et al. Does disinfection of environmental surfaces influence nosocomial infection rates? A systematic review. Am J Infect Control 2004;32:84–9. 10.1016/j.ajic.2003.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zingg W, Holmes A, Dettenkofer M, et al. Hospital organisation, management, and structure for prevention of health-care-associated infection: a systematic review and expert consensus. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15:212–24. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70854-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simon M, Maben J, Murrells T, et al. Is single room Hospital accommodation associated with differences in healthcare-associated infection, falls, pressure ulcers or medication errors? a natural experiment with non-equivalent controls. J Health Serv Res Policy 2016;21:147–55. 10.1177/1355819615625700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barratt RL, Shaban R, Moyle W. Patient experience of source isolation: lessons for clinical practice. Contemp Nurse 2011;39:180–93. 10.5172/conu.2011.180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abad C, Fearday A, Safdar N. Adverse effects of isolation in hospitalised patients: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect 2010;76:97–102. 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2015. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/193736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria, 2018. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schwarzer G. Meta: an R package for meta-analysis. R News 2007;7:40–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Viechtbauer W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J Stat Softw 2010;36 10.18637/jss.v036.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Day HR, Perencevich EN, Harris AD, et al. Association between contact precautions and delirium at a tertiary care center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012;33:34–9. 10.1086/663340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Day HR, Perencevich EN, Harris AD, et al. Depression, anxiety, and moods of hospitalized patients under contact precautions. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013;34:251–8. 10.1086/669526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lupión-Mendoza C, Antúnez-Domínguez MJ, González-Fernández C, et al. Effects of isolation on patients and staff. Am J Infect Control 2015;43:397–9. 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Soon MML, Madigan E, Jones KR, et al. An exploration of the psychologic impact of contact isolation on patients in Singapore. Am J Infect Control 2013;41:e111–3. 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tarzi S, Kennedy P, Stone S, et al. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: psychological impact of hospitalization and isolation in an older adult population. J Hosp Infect 2001;49:250–4. 10.1053/jhin.2001.1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tran K, Bell C, Stall N, et al. The effect of hospital isolation precautions on patient outcomes and cost of care: a multi-site, retrospective, propensity score-matched cohort study. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:262–8. 10.1007/s11606-016-3862-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guilley-Lerondeau B, Bourigault C, Guille des Buttes A-C, et al. Adverse effects of isolation: a prospective matched cohort study including 90 direct interviews of hospitalized patients in a French university hospital. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2017;36:75–80. 10.1007/s10096-016-2772-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mehrotra P, Croft L, Day HR, et al. Effects of contact precautions on patient perception of care and satisfaction: a prospective cohort study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013;34:1087–93. 10.1086/673143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Livorsi DJ, Kundu MG, Batteiger B, et al. Effect of contact precautions for MRSA on patient satisfaction scores. J Hosp Infect 2015;90:263–6. 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Evans HL, Shaffer MM, Hughes MG, et al. Contact isolation in surgical patients: a barrier to care? Surgery 2003;134:180–8. 10.1067/msy.2003.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Croft LD, Liquori M, Ladd J, et al. The effect of contact precautions on frequency of hospital adverse events. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015;36:1268–74. 10.1017/ice.2015.192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Saint S, Higgins LA, Nallamothu BK, et al. Do physicians examine patients in contact isolation less frequently? a brief report. Am J Infect Control 2003;31:354–6. 10.1016/S0196-6553(02)48250-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Masse V, Valiquette L, Boukhoudmi S, et al. Impact of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus contact isolation units on medical care. PLoS One 2013;8:e57057 10.1371/journal.pone.0057057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lau D, Majumdar SR, McAlister FA. Patient isolation precautions and 30-day risk of readmission or death after hospital discharge: a prospective cohort study. Int J Infect Dis 2016;43:74–6. 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Spence MR, McQuaid M. The interrelationship of isolation precautions and adverse events in an acute care facility. Am J Infect Control 2011;39:154–5. 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.04.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stelfox HT. Safety of patients isolated for infection control. JAMA 2003;290:1899 10.1001/jama.290.14.1899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gammon J. Analysis of the stressful effects of hospitalisation and source isolation on coping and psychological constructs. Int J Nurs Pract 1998;4:84–96. 10.1046/j.1440-172X.1998.00084.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Findik UY, Ozbaş A, Cavdar I, et al. Effects of the contact isolation application on anxiety and depression levels of the patients. Int J Nurs Pract 2012;18:340–6. 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2012.02049.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kennedy P, Hamilton LR. Psychological impact of the management of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1997;35:617–9. 10.1038/sj.sc.3100469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Day HR, Morgan DJ, Himelhoch S, et al. Association between depression and contact precautions in veterans at hospital admission. Am J Infect Control 2011;39:163–5. 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Colorado B, Del Toro D, Tarima S. Impact of contact isolation on FIM score change, FIM efficiency score, and length of stay in patients in acute inpatient rehabilitation facility. PM&R 2014;6:988–91. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dashiell-Earp CN, Bell DS, Ang AO, et al. Do physicians spend less time with patients in contact isolation?: a time-motion study of internal medicine interns. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:814–5. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gandra S, Barysauskas CM, Mack DA, et al. Impact of contact precautions on falls, pressure ulcers and transmission of MRSA and VRE in hospitalized patients. J Hosp Infect 2014;88:170–6. 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kirkland KB, Weinstein JM. Adverse effects of contact isolation. Lancet 1999;354:1177–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04196-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Day HR, Perencevich EN, Harris AD, et al. Do contact precautions cause depression? A two-year study at a tertiary care medical centre. J Hosp Infect 2011;79:103–7. 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wassenberg MWM, Severs D, Bonten MJM. Psychological impact of short-term isolation measures in hospitalised patients. J Hosp Infect 2010;75:124–7. 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis effect size calculator, 2019. Available: https://campbellcollaboration.org/research-resources/effect-size-calculator.html [Accessed 14 Aug 2019].

- 44. Chittick P, Koppisetty S, Lombardo L, et al. Assessing patient and caregiver understanding of and satisfaction with the use of contact isolation. Am J Infect Control 2016;44:657–60. 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Davies H, Rees J. Psychological effects of isolation nursing (1): mood disturbance. Nurs Stand 2000;14:35–8. 10.7748/ns2000.03.14.28.35.c2799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rees J, Davies HR, Birchall C, et al. Psychological effects of source isolation nursing (2): patient satisfaction. Nurs Stand 2000;14:32–6. 10.7748/ns2000.04.14.29.32.c2805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wilkins EG, Ellis ME, Dunbar EM, et al. Does isolation of patients with infections induce mental illness? J Infect 1988;17:43–7. 10.1016/S0163-4453(88)92308-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses, 2019. Available: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp [Accessed 14 Aug 2019].

- 49. Cohen CC, Cohen B, Shang J. Effectiveness of contact precautions against multidrug-resistant organism transmission in acute care: a systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Infect 2015;90:275–84. 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Landelle C, Pagani L, Harbarth S. Is patient isolation the single most important measure to prevent the spread of multidrug-resistant pathogens? Virulence 2013;4:163–71. 10.4161/viru.22641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Santos RP, Mayo TW, Siegel JD. Healthcare epidemiology: active surveillance cultures and contact precautions for control of multidrug-resistant organisms: ethical considerations. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:110–6. 10.1086/588789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, et al. Grade evidence to decision (ETD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: clinical practice guidelines. BMJ;2016:i2089 10.1136/bmj.i2089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jeong H, Yim HW, Song Y-J, et al. Mental health status of people isolated due to middle East respiratory syndrome. Epidemiol Health 2016;38:e2016048 10.4178/epih.e2016048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Madsen AF. Experience of source isolation during hospitalization – a qualitative study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2015;4 10.1186/2047-2994-4-S1-P95 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rechel B. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies : Investing in hospitals of the future. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Persson E, Anderberg P, Ekwall AK, Kristensson Ekwall A. A room of one's own--Being cared for in a hospital with a single-bed room design. Scand J Caring Sci 2015;29:340–6. 10.1111/scs.12168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Roth JA, Hornung-Winter C, Radicke I, et al. Direct costs of a contact isolation day: a prospective cost analysis at a Swiss university hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2018;39:101–3. 10.1017/ice.2017.258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030371supp001.pdf (80.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030371supp002.pdf (66.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030371supp003.pdf (74.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030371supp004.xls (61KB, xls)

bmjopen-2019-030371supp005.pdf (2.5MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030371supp006.pdf (80.4KB, pdf)