Abstract

Objective

To investigate the prevalence and risk factors of functional decline during hospitalisation and its relationship with postdischarge outcomes in very old patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) hospitalisation.

Design

Prospective cohort study between 1 October 2014 and 31 March 2016.

Setting

A physician-initiated, multicentre study of consecutive patients admitted for ADHF in 19 hospitals throughout Japan.

Participants

Among 3555 patients hospitalised for ADHF (median age (IQR), 80 (71–86) years; 1572 (44%) women), functional decline during the index hospitalisation occurred in 528 patients (15%).

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome measure was a composite of all-cause death or heart failure (HF) hospitalisation after discharge. The secondary outcome measures were all-cause death, HF hospitalisation, and a composite of all-cause death or all-cause hospitalisation.

Results

The independent risk factors for functional decline included age ≥80 years (OR 2.71; 95% CI 2.09 to 3.51), female (OR 1.32; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.67), prior stroke (OR 1.67; 95% CI 1.28 to 2.19), dementia (OR 2.26; 95% CI 1.74 to 2.95), ambulatory before admission (OR 1.74; 95% CI 1.29 to 2.35), elevated body temperature (OR 1.91; 95% CI 1.31 to 2.79), New York Heart Association class III or IV on admission (OR 1.54; 95% CI 1.07 to 2.22), decreased albumin levels (OR 1.76; 95% CI 1.32 to 2.34), hyponatraemia (OR 1.49; 95% CI 1.10 to 2.03) and renal dysfunction (OR 1.55; 95% CI 1.22 to 1.98), after multivariable adjustment. The cumulative 1-year incidence of the primary outcome in the functional decline group was significantly higher than that in the no functional decline group (50% vs 31%, log-rank p<0.001). After adjusting for baseline characteristics, the higher risk of the functional decline group relative to the no functional decline group remained significant (adjusted HR 1.46; 95% CI 1.24 to 1.71; p<0.001).

Conclusions

Independent risk factors of functional decline in very old patients with ADHF were related to both frailty and severity of HF. Functional decline during ADHF hospitalisation was associated with unfavourable postdischarge outcomes.

Trial registration number

NCT02334891, UMIN000015238.

Keywords: heart failure, adult cardiology, cardiac epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first, large-scale, contemporary, multicentre, observational study reporting the prevalence of functional decline in very old patients hospitalised for acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF).

The data for this study were prospectively collected from consecutive patients who had hospital admission due to ADHF in the real-world clinical practice in Japan.

This study examines the risk factors of functional decline in very old patients hospitalised for ADHF and whether functional decline during the index hospitalisation was associated with worse postdischarge outcomes.

We did not collect data regarding on-site and outpatient rehabilitation and nutritional support.

Introduction

Functional decline in hospitalised patients is a complex and dynamic process.1–3 Functional decline during hospitalisation was reported to occur in approximately 30%–50% of patients hospitalised for acute medical illness.2 4 5 In the rapidly ageing societies, the number of very old patients hospitalised for acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is increasing, and ADHF has become the leading cause of hospitalisation due to acute medical illness. In older patients, functional decline associated with hospitalisation often leads to subsequent inability to live actively and independently.

However, there is a scarcity of data regarding the risk factors of functional decline in very old patients hospitalised for ADHF. Identifying high-risk patients for functional decline during hospitalisation would be useful for its prevention. Furthermore, no previous study has focused on subsequent clinical outcomes in patients with functional decline during hospitalisation. Therefore, we sought to clarify the risk factors for functional decline during hospitalisation in very old patients with ADHF and to compare the 1-year clinical outcomes between the two groups of patients with and without functional decline during hospitalisation for ADHF in a large Japanese observational database of hospitalised patients for ADHF in the real-world clinical practice.

Methods

Study design, setting and population

The Kyoto Congestive Heart Failure (KCHF) registry is a physician-initiated, prospective, observational, multicentre cohort study that enrolled consecutive patients who were hospitalised for ADHF for the first time between 1 October 2014 and 31 March 2016. These patients were admitted into 19 secondary and tertiary hospitals, including rural and urban as well as large and small institutions, throughout Japan. The study met the conditions of the Japanese ethical guidelines for epidemiological study and the US policy for protecting human research participants.6 7 This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guideline.

The details of the KCHF study design and patient enrolment are described elsewhere.8–11 Briefly, we enrolled all patients with ADHF, as defined by the modified Framingham criteria, who were admitted to the participating hospitals and patients who underwent heart failure-specific treatment involving intravenous drugs within 24 hours after hospital presentation. Patient records were anonymised before analysis. Data analysis was conducted from August 2018 to October 2018.

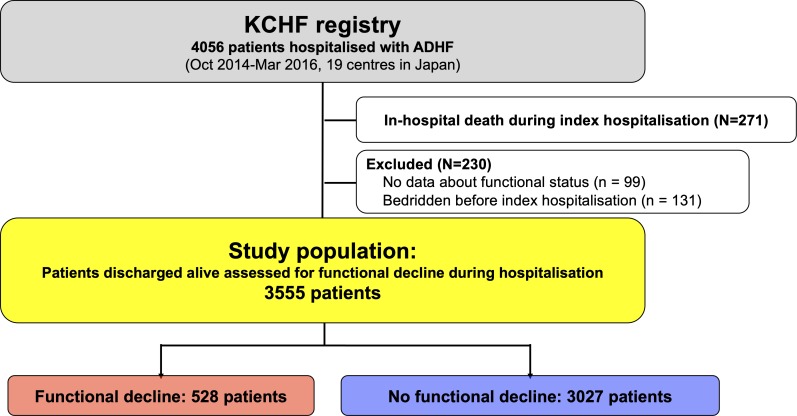

Among 4056 patients enrolled in the KCHF registry, 3785 patients were discharged alive after hospitalisation for ADHF. Clinical follow-up data were collected in October 2017. The attending physicians or research assistants at each participating hospital collected clinical events after the index hospitalisation from hospital charts or by contacting patients, their relatives or their referring physicians with consent. The present analysis had two objectives. First, we sought to clarify the risk factors for functional decline during hospitalisation of patients with ADHF. Second, we sought to compare the 1-year clinical outcomes between the two groups of patients with and without functional decline during the hospitalisation for ADHF. Among 4056 patients enrolled in the KCHF registry, the current study population consisted of 3555 patients who were discharged alive and were assessed for functional decline during hospitalisation, excluding 271 patients who died during the index hospitalisation, 99 patients whose functional status before admission and/or at discharge was not available, and 131 patients who were bedridden before index hospitalisation (figure 1). The long-term follow-up was censored at 1 year. The primary outcome measure in the current analysis was a composite of all-cause death or heart failure hospitalisation at 1 year. The secondary outcome measures were all-cause death, heart failure hospitalisation, and a composite of all-cause death or all-cause hospitalisation at 1 year.

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart. ADHF, acute decompensated heart failure; KCHF, Kyoto Congestive Heart Failure.

Definitions

Physical activity before admission and at discharge was classified by mobility status based on the definition of the Japanese long-term care insurance into ambulatory (including those patients using any aid such as stick), use of wheelchair outdoor only, use of wheelchair indoor and outdoor, and bedridden state.8 Functional decline was defined as the decline of at least one stage on physical activity at discharge compared with preadmission status. In-hospital worsening heart failure was defined as additional intravenous drug administration for heart failure, haemodialysis, or mechanical circulatory or respiratory support, occurring >24 hours after therapy initiation.12 In-hospital worsening renal function was defined as >0.3 mg/dL increase in serum creatinine levels during the index hospitalisation.13–15 Detailed definitions of baseline clinical characteristics including the signs and symptoms of heart failure have been described previously.9 Missing values are presented in online supplementary eTable 1.

bmjopen-2019-032674supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as numbers with percentages and compared using χ2 test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean with SD or median with 25th–75th percentiles, and compared using the Student’s t-test when normally distributed or Wilcoxon rank-sum test when not normally distributed.

We compared baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes based on the presence or absence of functional decline during the index hospitalisation. A multivariable logistic regression model was developed to identify clinical characteristics associated with an increased risk for functional decline. We used 24 clinically relevant factors listed in table 1 as potential independent risk factors in multivariable logistic regression models and estimated the OR and 95% CI. We used the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate the cumulative 1-year incidences of the outcome measures and assessed the differences with the log-rank test. We expressed the associations of the functional decline group with the no functional decline group for all outcome measures as HR with 95% CI by multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, incorporating 30 clinically relevant risk-adjusting variables indicated in table 1. We also conducted subgroup analyses stratified by age, sex, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), anaemia, albumin levels, body temperature and the symptomatic status at discharge (oedema and general malaise at discharge). In the multivariable analysis and subgroup analyses, continuous variables were dichotomised by clinically meaningful reference values or median values: age ≥80 years based on the median value, LVEF <40% based on the heart failure guideline of LVEF classification,16 body mass index ≤22 kg/m2, renal dysfunction (estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min/1.73 m2) based on chronic kidney disease grade, decreased albumin levels (serum albumin <3.0 g/dL), hyponatraemia (serum sodium <135 mEq/L), and elevated body temperature (body temperature ≥37.5°C) based on the cut-off value in metabolic syndrome.17

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Functional decline | No functional decline | P value | |

| n=528 | n=3027 | ||

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age, years | 85 (80–89) | 79 (70–85) | <0.001 |

| ≥80 years*† | 399 (76) | 1407 (46) | <0.001 |

| Women*† | 294 (56) | 1278 (42) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.0±4.0 | 23.1±4.5 | <0.001 |

| ≤22 kg/m2*† | 269 (55) | 1281 (44) | <0.001 |

| Medical history | |||

| Heart failure hospitalisation*† | 186 (36) | 1077 (36) | 0.92 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 220 (42) | 1263 (42) | 0.98 |

| Hypertension*† | 406 (77) | 2174 (72) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus*† | 187 (35) | 1145 (38) | 0.29 |

| Myocardial infarction*† | 112 (21) | 681 (23) | 0.51 |

| Stroke*† | 125 (24) | 432 (14) | <0.001 |

| Currently smoking*† | 28 (5.5) | 425 (14) | <0.001 |

| Malignancy | 97 (18) | 419 (14) | 0.006 |

| Chronic lung disease*† | 41 (7.8) | 247 (8.2) | 0.76 |

| Dementia*† | 175 (33) | 423 (14) | <0.001 |

| Social background on admission | |||

| Poor medical adherence | 100 (19) | 498 (16) | 0.16 |

| Living alone*† | 127 (24) | 652 (22) | 0.20 |

| Public assistance | 24 (4.6) | 186 (6.1) | 0.14 |

| Functional status before admission | |||

| Ambulatory*† | 420 (80) | 2529 (84) | 0.02 |

| Use of wheelchair (outdoor only) | 80 (15) | 192 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Use of wheelchair (outdoor and indoor) | 28 (5.3) | 306 (10) | <0.001 |

| Origin | |||

| Ischaemic | 134 (25) | 820 (27) | 0.41 |

| Acute coronary syndrome*† | 36 (6.8) | 166 (5.5) | 0.22 |

| Hypertensive | 131 (25) | 754 (25) | 0.96 |

| Valvular | 124 (23) | 565 (19) | <0.001 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 54 (10) | 492 (16) | <0.001 |

| Vital signs and symptoms on presentation | |||

| BP, mm Hg | |||

| Systolic BP | 144±32 | 149±35 | 0.003 |

| Systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg | 275 (53) | 1741 (58) | 0.03 |

| Systolic BP <90 mm Hg*† | 12 (2.3) | 76 (2.5) | 0.76 |

| Diastolic BP | 81±23 | 86±24 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 93±27 | 96±28 | 0.001 |

| <60 beats/min*† | 44 (8.5) | 195 (6.5) | 0.11 |

| Body temperature, °C | 36.6±0.7 | 36.5±0.6 | <0.001 |

| ≥37.5 °C*† | 58 (11) | 154 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| Rhythms on presentation | |||

| Sinus rhythm | 280 (53) | 1715 (57) | 0.12 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter*† | 198 (38) | 1085 (36) | 0.47 |

| NYHA class III or IV*† | 482 (92) | 2598 (73) | <0.001 |

| Tests on admission | |||

| LVEF | 48±16 | 46±16 | 0.02 |

| HFrEF (EF <40%)*† | 167 (32) | 1148 (38) | 0.006 |

| HFmrEF (EF 40%–49%) | 117 (22) | 566 (19) | 0.06 |

| HFpEF (EF ≥50%) | 242 (46) | 1305 (43) | 0.24 |

| Haemoglobin, g/L | 110±21 | 117±24 | <0.001 |

| Anaemia*†‡ | 401 (76) | 1946 (64) | <0.001 |

| BNP, pg/mL | 782 (448–1410) | 687 (375–1214) | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 10 795 (3450–18 000) | 5416 (2629–11 438) | 0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.2 (0.8–1.6) | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 0.21 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 38 (24–54) | 46 (30–62) | <0.001 |

| <30 mL/min/1.73 m2*† | 195 (37) | 747 (25) | <0.001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 28 (20–39) | 23 (17–33) | <0.001 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.3±0.5 | 3.5±0.5 | <0.001 |

| <3.0 g/dL*† | 112 (22) | 332 (11) | <0.001 |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 138±4.7 | 139±4.1 | <0.001 |

| <135 mEq/L*† | 83 (16) | 325 (11) | 0.001 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 4.3±0.8 | 4.2±0.6 | 0.03 |

| Clinical signs and symptoms at discharge | |||

| Oedema† | 89 (17) | 320 (11) | <0.001 |

| General malaise† | 152 (31) | 388 (14) | <0.001 |

| Medications at discharge | |||

| Number of drugs prescribed | 8 (6–11) | 9 (6–11) | 0.12 |

| Loop diuretics† | 428 (81) | 2472 (82) | 0.74 |

| ACEI or ARB† | 242 (46) | 1838 (61) | <0.001 |

| MRA† | 208 (39) | 1409 (47) | 0.002 |

| Beta blocker† | 287 (54) | 2101 (69) | <0.001 |

| Tolvaptan | 76 (14) | 299 (9.9) | 0.002 |

| Functional status at discharge | |||

| Ambulatory | 0 | 2682 (89) | <0.001 |

| Use of wheelchair (outdoor only) | 184 (35) | 160 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| Use of wheelchair (outdoor and indoor) | 261 (49) | 185 (6.1) | <0.0001 |

| Bedridden | 83 (16) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Living place after discharge | |||

| Home | 247 (47) | 2709 (90) | <0.001 |

| Hospital | 225 (43) | 180 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Institution for the aged | 50 (9.5) | 114 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Other | 4 (0.8) | 17 (0.6) | 0.59 |

Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD or median with (IQR). Categorical variables are presented as number (percentage).

*Risk-adjusting variables were selected for multivariable logistic regression models.

†Risk-adjusting variables were selected for multivariable Cox proportional hazard models.

‡Defined by the WHO criteria (haemoglobin <12 g/dL for women and <13 g/dL for men).

ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BNP, brain-type natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; EF, ejection fraction; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HFmrEF, heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT-proBNP, N-terminal-proBNP; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

We performed an additional analysis including data of those patients who died during the index hospitalisation and those who were bedridden before the index hospitalisation, and evaluated the factors associated with functional decline or in-hospital mortality by constructing the multivariable adjusted Cox models. All statistical analyses were conducted by a physician (HY) and a statistician (TM) using JMP V.13.0 or SAS V.9.4. Two-tailed p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics

Among 3555 study patients, physical activity before admission included ambulatory in 2949 patients (83%), use of wheelchair outdoor only in 272 patients (7.7%), and use of wheelchair outdoor and indoor in 334 patients (9.4%). At hospital discharge, functional decline was observed in 420 patients (14%) who were ambulatory before admission, in 80 patients (29%) who had used wheelchair outdoor only, and in 28 patients (8.4%) who had used wheelchair outdoor and indoor. Consequently, decline in functional status was observed in 528 patients (15%; functional decline group), while functional decline was not observed in 3027 patients (85%; no functional decline group) (online supplementary eFigure 1). Use of wheelchair outdoor only before admission was more prevalent in the functional decline group than in the no functional decline group; however, 80% of patients in the functional decline group were ambulatory before admission (table 1).

Regarding the baseline clinical characteristics, the patients in the functional decline group were older and had a higher prevalence of hypertension, prior stroke, renal dysfunction, dementia, malignancy, anaemia, decreased albumin levels and hyponatraemia (table 1). There were no significant differences in previous heart failure hospitalisation, atrial fibrillation or flutter, previous myocardial infarction, chronic lung disease, and living alone status as a social background between the two groups (table 1). The functional decline group was more likely to have a valvular aetiology, lower blood pressure, lower heart rate, higher levels of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal portion of proBNP, and a higher LVEF (table 1). The proportion of patients who achieved relief of signs and symptoms on admission after treatment in the emergency room was not significantly different between the two groups (14% vs 16%, p=0.25).

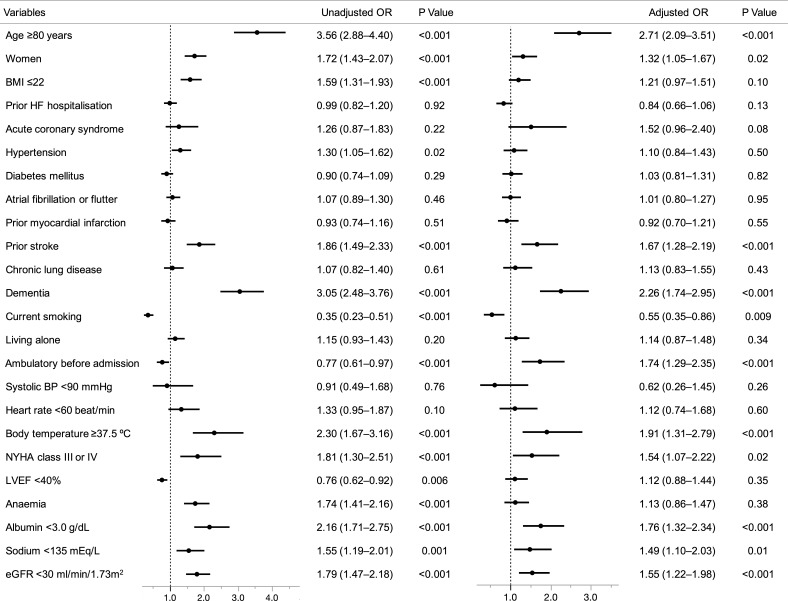

Risk factors for functional decline

Among the baseline characteristics and status on hospital presentation, the following independent risk factors for functional decline during hospitalisation were identified by the multivariable logistic regression analysis: age ≥80 years (OR 2.71; 95% CI 2.09 to 3.51), female (OR 1.32; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.67), prior stroke (OR 1.67; 95% CI 1.28 to 2.19), dementia (OR 2.26; 95% CI 1.74 to 2.95), ambulatory before admission (OR 1.74; 95% CI 1.29 to 2.35), elevated body temperature (OR 1.91; 95% CI 1.31 to 2.79), New York Heart Association class III or IV on admission (OR 1.54; 95% CI 1.07 to 2.22), decreased albumin levels (OR 1.76; 95% CI 1.32 to 2.34), hyponatraemia (OR 1.49; 95% CI 1.10 to 2.03) and renal dysfunction (OR 1.55; 95% CI 1.22 to 1.98) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinical factors associated with functional decline during hospitalisation in the univariate and multivariable logistic regression models. BP, blood pressure; BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

In-hospital adverse events and status at discharge

The median length of hospital stay was longer in the functional decline group than in the no functional decline group (21 days vs 15 days, p<0.001). Regarding in-hospital adverse events, the prevalence of worsening heart failure, worsening renal function and stroke was higher in the functional decline group than in the no functional decline group (table 2). The proportion of patients with symptoms such as oedema and general malaise at discharge was higher in the functional decline group than in the no functional decline group (table 1). Consequently, the proportion of patients in the functional decline group discharged to home was also lower (47% vs 90%, p<0.001). Regarding medical treatment at discharge, ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and beta blocker were less often prescribed in the functional decline group than in the no functional decline group (table 1).

Table 2.

In-hospital management and outcome

| Functional decline | No functional decline | P value | |

| n=528 | n=3027 | ||

| In-hospital management | |||

| Management in the emergency room | |||

| Respiratory management | |||

| Oxygen inhalation | 295 (56) | 1382 (46) | <0.001 |

| NIPPV | 82 (16) | 423 (14) | 0.35 |

| Intubation | 11 (2.1) | 53 (1.8) | 0.60 |

| Intravenous drugs within 24 hours after hospital presentation | |||

| Inotropes | 101 (19) | 405 (13) | <0.001 |

| Furosemide | 446 (85) | 2536 (84) | 0.69 |

| In-hospital clinical outcomes | |||

| In-hospital adverse events | |||

| Stroke | 27 (5.1) | 26 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Worsening heart failure | 130 (25) | 490 (16) | <0.001 |

| Worsening renal function | 244 (47) | 992 (33) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital infection | 104 (20) | 258 (8.5) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay, days | 21 (14–37) | 15 (11–22) | <0.001 |

NIPPV, non-invasive intermittent positive pressure ventilation.

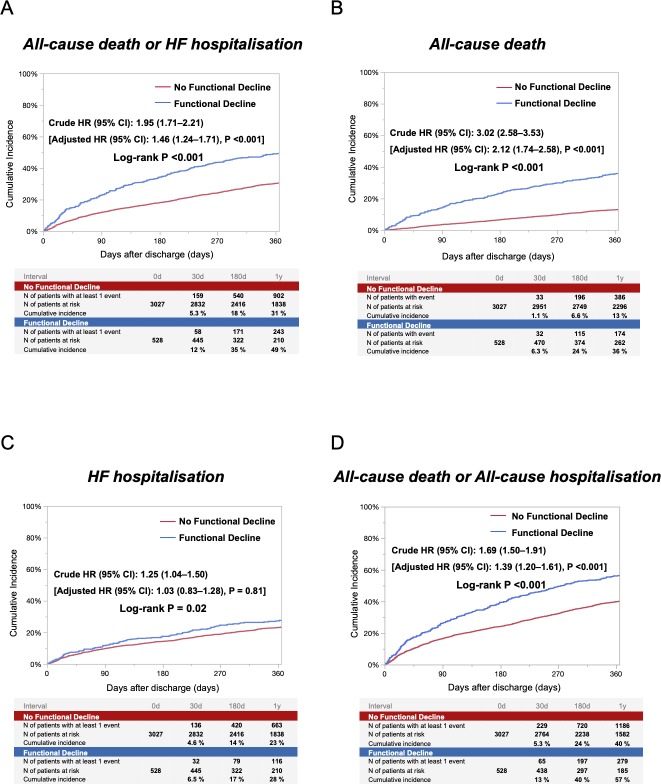

Long-term outcomes: functional decline versus no functional decline groups

The follow-up rate at 1 year was 96%. The cumulative 1-year incidence of the primary outcome measure (a composite of all-cause death or heart failure hospitalisation) in the functional decline group was significantly higher than that in the no functional decline group (49% vs 31%, log-rank p<0.001) (figure 3). After adjusting for baseline characteristics, the higher risk of the functional decline group relative to the no functional decline group remained significant (adjusted HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.24 to 1.71; p<0.001) (figure 3 and table 3). The cumulative 1-year incidence of all-cause death was also significantly higher in the functional decline group than in the no functional decline group. Even after adjusting for confounders, the excess mortality risk of the functional decline group relative to the no functional decline group remained significant (figure 3 and table 3). The cumulative 1-year incidence of heart failure hospitalisation was also significantly higher in the functional decline group than in the no functional decline group. However, the adjusted risk of the functional decline group relative to the no functional decline group for heart failure hospitalisation was no longer significant (figure 3 and table 3). The cumulative 1-year incidence of a composite of all-cause death or all-cause hospitalisation was significantly higher in the functional decline group than in the no functional decline group. After adjusting for confounders, the higher risk of the functional decline group relative to the no functional decline group remained significant (figure 3 and table 3). In the subgroup analyses, there were no interactions between those subgroup factors and the association of functional decline with the primary outcome measure (online supplementary eFigure 2).

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence for the primary outcome measure (A), all-cause death (B), HF hospitalisation (C), and a composite of all-cause death or all-cause hospitalisation (D), according to the presence or absence of functional decline. HF, heart failure.

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes in the entire cohort

| Outcomes | Functional decline | No functional decline | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) |

P value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

P value |

| Patients with event (n)/patients at risk (N) (cumulative 1-year incidence, %) | Patients with event (n)/patients at risk (N) (cumulative 1-year incidence, %)) | |||||

| All-cause death or HF hospitalisation | 243/528 (49) | 902/3027 (31) | 1.95 (1.71 to 2.21) | <0.001 | 1.46 (1.24 to 1.71) | <0.001 |

| All-cause death | 174/528 (36) | 386/3027 (13) | 3.02 (2.58 to 3.53) | <0.001 | 2.12 (1.74 to 2.58) | <0.001 |

| HF hospitalisation | 116/528 (28) | 663/3027 (23) | 1.25 (1.04 to 1.50) | 0.02 | 1.03 (0.83 to 1.28) | 0.81 |

| All-cause death or all-cause hospitalisation | 279/528 (57) | 1186/3027 (40) | 1.69 (1.50 to 1.91) | <0.001 | 1.39 (1.20 to 1.61) | <0.001 |

The number of patients with at least one event was counted through the 1-year follow-up period.

HF, heart failure.

Additional analysis on the risk factors for functional decline or in-hospital mortality

The risk factors for functional decline or in-hospital mortality in a total of 4056 patients were similar to the risk factors for functional decline. LVEF <40% (OR 1.24; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.52; p=0.047) and acute coronary syndrome (OR 1.76; 95% CI 1.19 to 2.60; p=0.005) which were not included as risk factors for functional decline emerged as risk factors for functional decline or in-hospital mortality (online supplementary eTable 2). Meanwhile, among the risk factors for functional decline, being female (OR 1.13; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.38; p=0.22) was not included as a risk factor for functional decline or in-hospital mortality (figure 2 and online supplementary eTable 2).

Discussion

The main findings of the present study investigating the prevalence and risk factors of functional decline during hospitalisation and its relationship with postdischarge outcomes in patients with ADHF hospitalisation were as follows: (1) functional decline during ADHF hospitalisation occurred in 15% of patients, and 80% of those with functional decline were ambulatory before admission; (2) the independent baseline risk factors associated with functional decline included age ≥80 years, female, prior stroke, dementia, ambulatory before admission, elevated body temperature, New York Heart Association class III or IV on admission, decreased albumin levels, hyponatraemia and renal dysfunction; and (3) functional decline during the index hospitalisation was associated with higher long-term risk for a composite of all-cause death or heart failure hospitalisation.

This is the first, large-scale, contemporary, multicentre study reporting the prevalence of functional decline in patients hospitalised for ADHF. Of note, we identified the severity of symptoms or patient status specific for heart failure was associated with functional decline independent of well-known factors in acute medical illness.18–20 Functional decline is an inevitable consequence in aged people, but hospitalisation accelerates the decline.20–22 Functional declines have been found to be related not only to impairment of independence and quality of life (QOL), but also to increased health service use, higher risk for institutionalisation and higher risk for mortality.23–27 Indeed, in the present study, the proportion of patients discharged to home was lower in the functional decline group than in the no functional decline group, suggesting impaired QOL after discharge. Also, long-term mortality was worse in the functional decline group than in the no functional decline group. Therefore, it is important to recognise risk factors of functional decline. In previous studies of hospitalised patients with acute medical illness, the predictors of functional decline in hospitalised elderly patients were older age, admission diagnosis, lower functional status, impaired cognitive status, comorbidities and length of hospital stay.18–20 These findings were confirmed in the setting of ADHF in our present study. In addition, findings specific for ADHF such as the dyspnoea or hyponatraemia were associated with functional decline, which were also reported to be risk factors for in-hospital mortality in ADHF.28 The prevalence of oedema and general malaise at discharge was higher in the functional decline group. Early achievement of successful ADHF treatment might reduce the risk of functional decline, although the present observational study could not address the cause–effect relationship between the functional decline and the symptomatic status at discharge.

There might be several possible strategies to prevent functional decline during ADHF hospitalisation. The first is the early improvement of haemodynamic status to avoid worsening heart failure. The prevalence of worsening heart failure was higher in the functional decline group. As functional decline associated with hospitalisation begins within 48 hours of admission, early improvement of heart failure to reduce the incidence of hospitalisation-associated disability is one of the main goals of care.28 Second, it would be important to be adequately aware that providing aggressive interventions prevents functional decline in high-risk patients. We identified the risk factors among the baseline characteristics in patients with ADHF. In addition, the adverse events during hospitalisation may be tightly related to the functional decline. Stroke is one of the causes of functional decline and is observed in 5.1% of patients with functional decline. Third, seamless rehabilitation and comprehensive geriatric management through a multidisciplinary team approach might be a strategy for the prevention of functional decline.29–32 In addition, the subgroup analysis showed that there were no interactions between those subgroup factors and the association of functional decline with the primary outcome measure. Thus, prevention of functional decline would have an impact on improving outcomes in all patients with ADHF. One possible strategy could be immediate, tailored physical function rehabilitation during and after heart failure hospitalisation.33

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we adopted simple classification of functional status based on the definition of the Japanese long-term care insurance: ambulatory, use of wheelchair outdoor only, use of wheelchair indoor and outdoor, and bedridden state. The categorisation scheme is an easy-to-understand but coarse measure with very large gradations inherent in each single stage and therefore very likely substantially underestimated the prevalence of meaningful functional decline. Second, we did not collect data regarding on-site and outpatient rehabilitation and nutritional support. However, a team-based approach for patients with heart failure was adapted in all the participating centres in the present study. Third, we did not include the status at discharge or adverse in-hospital events in the analysis for the risk factor for functional decline, because the cause–effect relationship was not clear. Fourth, data on postdischarge medication and change of functional status after discharge from the index hospitalisation were not collected and not analysed in the analysis for the long-term outcomes. Fifth, as with any observational study, the possibility of selection bias and residual confounding cannot be excluded, although we adjusted for 29 variables as most conceivable confounders.

Conclusions

The independent risk factors of functional decline in patients with ADHF were related to both frailty and severity of heart failure. Functional decline during ADHF hospitalisation was associated with unfavourable postdischarge outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the KCHF study investigators: Hidenori Yaku MD, Takao Kato MD, Neiko Ozasa MD, Erika Yamamoto MD, Yusuke Yoshikawa MD, Tetsuo Shioi MD, Koichiro Kuwahara MD, Takeshi Kimura MD, at Kyoto University Hospital, Kyoto, Japan; Moritake Iguchi MD, Yugo Yamashita MD, Masaharu Akao MD, at National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, Kyoto, Japan; Masashi Kato MD, Shinji Miki MD, at Mitsubishi Kyoto Hospital, Kyoto, Japan; Mamoru Takahashi MD, at Shimabara Hospital, Kyoto, Japan; Tsuneaki Kawashima MD, Takafumi Yagi MD, at Okamoto Memorial Hospital; Toshikazu Jinnai MD, Takashi Konishi MD, at Japanese Red Cross Otsu Hospital, Otsu, Japan; Yasutaka Inuzuka MD, Shigeru Ikeguchi MD, at Shiga General Hospital, Moriyama, Japan; Tomoyuki Ikeda MD, Yoshihiro Himura MD, at Hikone Municipal Hospital, Hikone, Japan; Kazuya Nagao MD, Tsukasa Inada MD, at Osaka Red Cross Hospital, Osaka, Japan; Kenichi Sasaki MD, Moriaki Inoko MD, at Kitano Hospital, Osaka, Japan; Takafumi Kawai MD, Tomoki Sasa MD, Mitsuo Matsuda MD, at Kishiwada City Hospital, Kishiwada, Japan; Akihiro Komasa MD, Katsuhisa Ishii MD, at Kansai Electric Power Hospital, Osaka, Japan; Yodo Tamaki MD, Yoshihisa Nakagawa MD, at Tenri Hospital, Tenri, Japan; Ryoji Taniguchi MD, Yukihito Sato MD, Yoshiki Takatsu MD, at Hyogo Prefectural Amagasaki General Medical Center, Amagasaki, Japan; Takeshi Kitai MD, Ryousuke Murai MD, Yutaka Furukawa MD, at Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital, Kobe, Japan; Mitsunori Kawato MD, at Kobe City Nishi-Kobe Medical Center, Kobe, Japan; Yasuyo Motohashi MD, Kanae Su MD, Mamoru Toyofuku MD, Takashi Tamura MD, at Japanese Red Cross Wakayama Medical Center, Wakayama, Japan; Reiko Hozo MD, Ryusuke Nishikawa MD, Hiroki Sakamoto MD, at Shizuoka General Hospital, Shizuoka, Japan; Yuichi Kawase MD, Keiichiro Iwasaki MD, Kazushige Kadota MD, at Kurashiki Central Hospital, Kurashiki, Japan; and Takashi Morinaga MD, Yohei Kobayashi MD, Kenji Ando MD, at Kokura Memorial Hospital, Kokura, Japan.

Footnotes

Contributors: HY and TKa had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: HY, TKa, TM, YT, NO, EY, TKit, MK, TKim. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: HY, TKa, TM, YI, YT, YY, TI, YF, KK. Drafting of the manuscript: HY, TKa, TKim. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: HY, TKa, TM, YI, YT, EY, YY, TKit, KK, TKim. Statistical analysis: HY, TKa, TM. Administrative, technical or material support: TKa, YS, TKim. Supervision: YI, NO, TKi, YF, YN, YS, KK, TKim.

Funding: This study is supported by a grant from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (18059186) to TKa, KK and NO.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine (approval number: E2311), Shiga General Hospital (approval number: 20141120-01), Tenri Hospital (approval number: 640), Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital (approval number: 14094), Hyogo Prefectural Amagasaki General Medical Center (approval number: Rinri 26-32), National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center (approval number: 14-080), Mitsubishi Kyoto Hospital (approved 11/12/2014), Okamoto Memorial Hospital (approval number: 201503), Japanese Red Cross Otsu Hospital (approval number: 318), Hikone Municipal Hospital (approval number: 26-17), Japanese Red Cross Osaka Hospital (approval number: 392), Shimabara Hospital (approval number: E2311), Kishiwada City Hospital (approval number: 12), Kansai Electric Power Hospital (approval number: 26-59), Shizuoka General Hospital (approval number: Rin14-11-47), Kurashiki Central Hospital (approval number: 1719), Kokura Memorial Hospital (approval number: 14111202), Kitano Hospital (approval number: P14-11-012), and Japanese Red Cross Wakayama Medical Center (approval number: 328). A waiver of written informed consent from each patient was granted by the institutional review boards of Kyoto University and each participating centre.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. No additional data available.

References

- 1. Manton KG. A longitudinal study of functional change and mortality in the United States. J Gerontol 1988;43:S153–61. 10.1093/geronj/43.5.S153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boyd CM, Ricks M, Fried LP, et al. Functional decline and recovery of activities of daily living in hospitalized, disabled older women: the women's health and aging study I. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1757–66. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02455.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guralnik JM, Alecxih L. Medical and long-term care costs when older persons become more dependent intentional weight loss and 13-year diabetes incidence in overweight adults. Am J Public Health 2002;92:1244–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, et al. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA 2004;292:2115–24. 10.1001/jama.292.17.2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sager MA, Franke T, Inouye SK, et al. Functional outcomes of acute medical illness and hospitalization in older persons. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:645–52. 10.1001/archinte.1996.00440060067008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ethical guidelines for epidemiologic research Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Ministry of Health L and W. Japan’s, 2002. Available: http://www.lifescience.mext.go.jp/files/pdf/n796_01.pdf

- 7. 45 Code of Federal Regulations 46.116(d), 2009. Available: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html#46.116

- 8. Yamamoto E, Kato T, Ozasa N, et al. Kyoto congestive heart failure (KCHF) study: rationale and design. ESC Heart Fail 2017;4:216–23. 10.1002/ehf2.12138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yaku H, Ozasa N, Morimoto T, et al. Demographics, Management, and In-Hospital Outcome of Hospitalized Acute Heart Failure Syndrome Patients in Contemporary Real Clinical Practice in Japan - Observations From the Prospective, Multicenter Kyoto Congestive Heart Failure (KCHF) Registry. Circ J 2018;82:2811–9. 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yaku H, Kato T, Morimoto T, et al. Association of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist use with all-cause mortality and hospital readmission in older adults with acute decompensated heart failure. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e195892–14. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Su K, Kato T, Toyofuku M, et al. Association of previous hospitalization for heart failure with increased mortality in patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure. Circ Rep 2019;1:517–24. 10.1253/circrep.CR-19-0054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Butler J, Gheorghiade M, Kelkar A, et al. In-Hospital worsening heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2015;17:1104–13. 10.1002/ejhf.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Filippatos G, Farmakis D, Parissis J. Renal dysfunction and heart failure: things are seldom what they seem. Eur Heart J 2014;35:416–8. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vardeny O, Wu DH, Desai A, et al. Influence of baseline and worsening renal function on efficacy of spironolactone in patients with severe heart failure: insights from RALES (randomized Aldactone evaluation study). J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:2082–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clark H, Krum H, Hopper I. Worsening renal function during renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor initiation and long-term outcomes in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:41–8. 10.1002/ejhf.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016;37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oda E, Oohara K, Abe A, et al. The optimal cut-off point of C-reactive protein as an optional component of metabolic syndrome in Japan. Circ J 2006;70:384–8. 10.1253/circj.70.384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stuck AE, Walthert JM, Nikolaus T, et al. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med 1999;48:445–69. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00370-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McCusker J, Kakuma R, Abrahamowicz M. Predictors of functional decline in hospitalized elderly patients: a systematic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57:M569–77. 10.1093/gerona/57.9.M569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:451–8. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Baker DI, et al. The hospital elder life program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Hospital elder life program. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:1697–706. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03885.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-Term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1306–16. 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hirvensalo M, Rantanen T, Heikkinen E. Mobility difficulties and physical activity as predictors of mortality and loss of independence in the community-living older population. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:493–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04994.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Greiner PA, Snowdon DA, Schmitt FA. The loss of independence in activities of daily living: the role of low normal cognitive function in elderly nuns. Am J Public Health 1996;86:62–6. 10.2105/AJPH.86.1.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ganguli M, Seaberg E, Belle S, et al. Cognitive impairment and the use of health services in an elderly rural population: the movies project. Monongahela Valley independent elders survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993;41:1065–70. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06453.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barberger-Gateau P, Fabrigoule C. Disability and cognitive impairment in the elderly. Disabil Rehabil 1997;19:175–93. 10.3109/09638289709166525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Black SA, Rush RD. Cognitive and functional decline in adults aged 75 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1978–86. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50609.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hirsch CH, Sommers L, Olsen A, et al. The natural history of functional morbidity in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990;38:1296–303. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03451.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O'Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, et al. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;301:1439–50. 10.1001/jama.2009.454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baztán JJ, Suárez-García FM, López-Arrieta J, et al. Effectiveness of acute geriatric units on functional decline, living at home, and case fatality among older patients admitted to hospital for acute medical disorders: meta-analysis. BMJ 2009;338:b50–6. 10.1136/bmj.b50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fox MT, Persaud M, Maimets I, et al. Effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care using acute care for elders components: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:2237–45. 10.1111/jgs.12028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bachmann S, Finger C, Huss A, et al. Inpatient rehabilitation specifically designed for geriatric patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2010;340:c1718 10.1136/bmj.c1718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reeves GR, Whellan DJ, Duncan P, et al. Rehabilitation therapy in older acute heart failure patients (REHAB-HF) trial: design and rationale. Am Heart J 2017;185:130–9. 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-032674supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)