Abstract

Introduction

Around 70% to 80% of the 19 million visually disabled children in the world are due to a preventable or curable disease, if detected early enough. Vision screening in childhood is an evidence-based and cost-effective way to detect visual disorders. However, current screening programmes face several limitations: training required to perform them efficiently, lack of accurate screening tools and poor collaboration from young children.

Some of these limitations can be overcome by new digital tools. Implementing a system based on artificial intelligence systems avoid the challenge of interpreting visual outcomes.

The objective of the TrackAI Project is to develop a system to identify children with visual disorders. The system will have two main components: a novel visual test implemented in a digital device, DIVE (Device for an Integral Visual Examination); and artificial intelligence algorithms that will run on a smartphone to analyse automatically the visual data gathered by DIVE.

Methods and analysis

This is a multicentre study, with at least five centres located in five geographically diverse study sites participating in the recruitment, covering Europe, USA and Asia.

The study will include children aged between 6 months and 14 years, both with normal or abnormal visual development.

The project will be divided in two consecutive phases: design and training of an artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm to identify visual problems, and system development and validation. The study protocol will consist of a comprehensive ophthalmological examination, performed by an experienced paediatric ophthalmologist, and an exam of the visual function using a DIVE.

For the first part of the study, diagnostic labels will be given to each DIVE exam to train the neural network. For the validation, diagnosis provided by ophthalmologists will be compared with AI system outcomes.

Ethics and dissemination

The study will be conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice. This protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragón, CEICA, on January 2019 (Code PI18/346).

Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and disseminated in scientific meetings.

Trial registration number

Keywords: vision screening, artificial intelligence, visual impairment, childhood

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a multicentre study, including five geographically diverse study sites.

The study aims to overcome the main limitations of the current vision screening tools in childhood.

The main strength is its potential to include a large sample of children with a wide range of features, not only in terms of visual disorders, but also social, ethnic and geographical characteristics.

The main limitation lies in the number of ophthalmologists running the clinical protocol, which will be faced a with very exhaustive training programme and will receive detailed documentation describing the protocol.

Introduction

Background

The WHO estimates 19 million children in the world with visual impairment. Reports of the global magnitude and causes of visual impairments confirm that 70% to 80% of all visual impairment are either preventable or curable, if detected in time.1–3

There is an important shortage of paediatric ophthalmologists in the world to provide timely diagnosis. As a result, most of these children will remain undiagnosed for years, leading to consequences on their vision, general development, educational opportunities, social life and prospects.4 However, it is especially critical in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), where blind children face higher risk of death during childhood (60% of the children becoming blind in LMIC are thought to die during the first 2 years).5

Childhood blindness is a priority of ‘Vision 2020 the Right to Sight’.6 Since the highest incidence of visual problems occurs during the first 5 years of life, early detection of any potential disorder causing abnormal visual development is a priority. All the tools currently available to assess visual function require active collaboration from the patients and/or an experienced examiner. Incorporating an accurate and easy-to-use tool to identify children with abnormal visual development, as young as 6 months of age, would become a major opportunity to prevent visual impairment in childhood.

The major causes of visual impairment in childhood differ from country to country. In low-income regions nutritional and infectious conditions are the main causes for blindness. In particular, vitamin A deficiency, corneal scarring related to measles or ophthalmia neonatorum are common in certain countries of Asia or sub-Saharan Africa. Retinopathy of prematurity is causing major visual impairment in middle-income countries. Nevertheless, the aetiologies of severe visual deficiencies in developed countries are mainly hereditary and perinatal factors.7

Uncorrected refractive errors are cause of less severe visual impairment, but it is currently affecting around 12.8 million children aged from 5 to 15 years in the world, with the highest prevalence reported in urban areas of China and Southeast Asia.8 Increasing rates of myopia has become a concerning public health problem in wide regions.9 Finally, amblyopia is the result of different conditions, such as strabismus, uncorrected refractive errors or vision deprivation, that cause visual impairment, but avoidable if treated in time. It is considered an alteration in the visual neural pathway in a child’s developing brain.10 Among children younger than 6 years, 1% to 4% present amblyopia or a condition which could lead to amblyopia if remains untreated.10 11 Therefore, screening for amblyopia is one of the most important goals in paediatric ophthalmology programmes.

Study justification

Systematic evaluation of visual function is critical to detect visual impairment, its causes and to plan therapeutic interventions. Screening programmes vary between countries, with low agreement in timing, target population or methods.12 There is solid evidence supporting visual screening between 3 to 5 years, but a lack of data from controlled studies under 3 years is pointed out.13 However, there is indirect evidence for preschool screening, as the better likelihood of improving visual acuity as the sooner amblyopia treatment starts.14

Vision screening in childhood is usually done in primary care settings, with different rates of coverage, lower than 50% among 3-year-old children and only 3% starting at age 6 months, even in developed countries.15 16 Children with abnormal findings in any screening programme should be referred for a complete eye examination, to confirm or rule out any visual disorder.

Current visual screening programmes face important limitations. As screening tools, clinical protocols should not be very time-consuming and must be, therefore, focussed on the most discriminative visual functions.17 That is why they are mostly limited to visual acuity tests, ocular alignment, stereoacuity and red reflex test. For children younger than 3 years, visual acuity assessment is usually replaced by the fixation and follow test.18 When screening protocols include further assessments, such as monocular autorefractors, less than 50% of the children younger than 3 years are testable with current screening tools.19 However, all these assessments require training and experience not only to properly perform them but also to interpret their outcomes. It gives rise to with higher false-positive and false-negative rates the lower the experience of the examiner. Such are the limitations of current visual screening tools that most paediatricians report being unsatisfied with them, mainly because of inadequate training to run them and the time required for the exam.16

Instrument-based techniques, such as autorefractors, had demonstrated utility in visual screening programmes, especially as an alternative to eye charts for very young children or children with developmental delays,17 but their utility is limited to refractive errors and do not seem to decrease the barriers perceived by the examiners.16

Study motivation

During the last years, our research group has worked in the development of a new medical device to provide an automated, fast and accurate exploration of the visual function even in non-collaborative patients. DIVE (Devices for an Integral Visual Examination, developed by DIVE Medical Startup) has been specially designed to explore vision in children, including infants from 6 months of age and children with developmental issues. DIVE explores several aspects of the visual function by presenting carefully designed stimuli on a high-resolution screen while collecting accurate gaze data from the patient using eye tracking technology. Although running the tests does not require any especial training or expertise, interpreting their outcomes may be challenging for non-experienced examiners. Besides, analysing gaze data requires parametrised algorithms and heuristics that complicate the task of generic gaze data processing for all ages and visual pathologies.

Artificial intelligence (AI) provides a valuable assistance for the interpretation of multiple biological outcomes. AI tools have shown to reach and even exceed performance of expert humans in certain clinical tasks, such as identifying retinal diseases or recommending referral.20 We expect AI to overcome most of the existing limitations of vision screening in childhood. It avoids the challenge of interpreting the outcomes, dealing with the wide range of clinical variability of visual disorders, differences in normal performance depending on the age and unstable collaboration from young children.

Finally, digital devices can contribute to improve children’s collaboration by providing a child-friendly tool. Using this new approach, visual function could be assessed in a quantitative and objective way, avoiding the lack of training personnel in certain areas, and improving quality of referrals.

Hypothesis

Children with visual disorders can be identified from children with a normally developed visual function using a trained neural network implemented in a DIVE.

Objectives

Primary objectives

To develop a system based on artificial intelligence algorithms to identify children with visual disorders, using a visual test implemented in a DIVE.

Secondary objectives

To describe visual development throughout childhood, from 6 months to 14 years of age.

To create normal reference databases for every age and visual test, assessing grating visual acuity, grating contrast sensitivity, colour perception and oculomotor control.

To identify different patterns of visual function related to the main causes of visual impairment in childhood in the world.

Methods

Study design

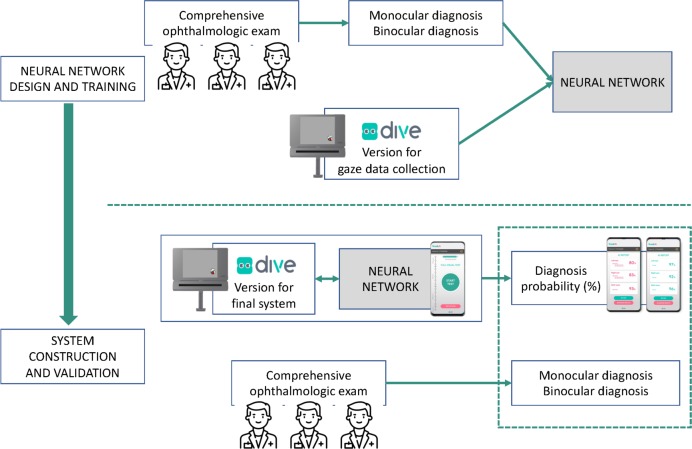

The study will consist of two consecutive phases, presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed artificial intelligence framework, representing consecutive neural network training and validation phases. DIVE, Device for an Integral Visual Examination.

In the first one, we will design and train an AI neural network, including the following steps:

Design of the visual exam to run in DIVE in order to collect binocular and monocular gaze data from oculomotor control, visual acuity, contrast sensitivity and colour perception tests. This test is based on existing larger versions of visual tests already validated and normalised. Consecutive pilot studies will be carried out to confirm feasibility and validity of the final version of the visual test. This exam must provide all the required data in the shortest time possible. This visual exam will be implemented in DIVE to enable systematic gaze data collection and storage.

Collection of monocular and binocular gaze data using DIVE, labelled by an experienced paediatric ophthalmologist as Normal visual function or Abnormal visual function. Those data sets labelled as Abnormal visual function will be also classified as Significant refractive error, Media opacity, Retinal disorder, Optic nerve disorder, Cerebral visual impairment, Strabismus or Other pathologies. Patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria will be recruited from at least five different paediatric ophthalmology units, from different countries.

Design and development of the supervised neural network models. The neural network will take as an input the results obtained from the DIVE exam and the gaze data logs recorded while the patient was tested for oculomotor control, visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, colour perception and quality of the calibration of the eye tracking system. These data will be available from both monocular and binocular exams, and will be completed with age and gender. The output of the neural network will be the probability for the patient to have normal or abnormal monocular and binocular visual function, and any of the pathologies listed in the previous paragraph.

During development, the AI algorithm will be trained providing the input and including the output as labels. Several options will be evaluated for the design of the neural network to process the gaze data log files, including long short-term memory (LSTM) layers and a series of convolutional layers. The output values will be concatenated and fed into fully connected layers in order to produce the final result.

Training of the neural network models. Collected patient data will be used to train the neural network. Note that to generate the monocular diagnosis probabilities, each eye of the patient will be considered independently, thus roughly doubling the amount of training data.

First, the complete system to identify visual pathologies will be built. The system will be composed of a DIVE device and a Huawei P30 smartphone, which will communicate via Bluetooth. The doctor will use the smartphone to control gaze data collection, which will happen through the DIVE device, thus reducing the doctor’s interference in the visual exam. At the end of the exam, the collected data will run through the trained neural network to produce the probability for the patient to have normal or abnormal visual development, and the pathologies listed above.

Second, the diagnostic accuracy of the system will be compared with the diagnosis provided by paediatric ophthalmologists.

In the second phase, we will construct and validate the system, with the following steps:

First, the complete system to identify visual pathologies will be built. The system will be composed of a DIVE device and a Huawei P30 smartphone, which will communicate via Bluetooth. The doctor will use the smartphone to control gaze data collection, which will happen through the DIVE device, thus reducing the doctor’s interference in the visual exam. At the end of the exam, the collected data will run through the trained neural network to produce the probability for the patient to have normal or abnormal visual development, and the pathologies listed above.

Second, the diagnostic accuracy of the system will be compared with the diagnosis provided by paediatric ophthalmologists.

Study setting

This study will be coordinated by the Vision, Image and Neurodevelopment Research Group, from the Instituto de Investigacion Sanitaria de Aragon (IIS Aragon), in Zaragoza, Spain. The recruitment of participants will be conducted in at least five geographically diverse study sites, covering Europe, Asia and USA.

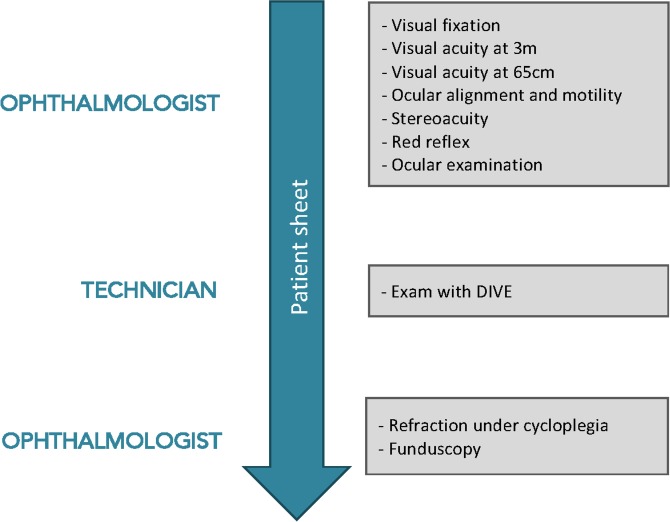

Study protocol

The study protocol will consist of the following steps, as presented in figure 2:

Figure 2.

Steps of the study clinical protocol. DIVE, Device for an Integral Visual Examination.

-

Comprehensive ophthalmological examination, performed by an experienced paediatric ophthalmologist, including:

Oculomotor control, including fixation, smooth pursuit and saccadic performance;

Monocular uncorrected visual acuity at 3 m, tailored to the child’s age and level of cooperation, using LEA grating test from 6 months to 2 years, LEA symbols chart from 2 to 4 years and Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) visual acuity chart over 5 years of age;

Monocular uncorrected visual acuity at 65 cm with a LEA symbols near vision card;

Ocular alignment, using Hirschberg test or cover test for children younger or older than 3 years respectively;

Ocular motility, including ductions and versions;

Stereopsis evaluation, with Titmus stereotest;

Red reflex test;

Ocular examination, by ocular inspection or slit lamp exam.

DIVE exam, which will be run by an optometrist.

Funduscopy, refraction under cycloplegia and best-corrected visual acuity.

Equipment

For this study, a DIVE will be used. It includes a 12-inch screen, corresponding to a visual angle of 22.11 degrees horizontally and 14.81 degrees vertically, assisted by eye tracking, with a maximum temporal resolution of 120 Hz. A child-friendly digital test has been specifically designed for TrackAI Project. It includes carefully designed and validated visual stimuli, to assess oculomotor control, visual acuity, contrast sensitivity and colour perception, both monocularly and binocularly.

DIVE exam will be performed in a quiet room under mesopic ambient illumination. Children will be positioned on a chair at approximately 65 cm from the screen and asked to fixate on the different stimuli on the screen, trying not to move their heads.

Before starting the exam, DIVE shows on the screen a drawing of the eyes of the patient as they are captured by the eye tracker, and two ovals that represent the ideal position and size the eyes should have on the screen and must be used as a guideline. To ensure the child is positioned at the optimal relative height and distance from the screen, the patient and the DIVE must be adjusted so that the drawing of the eyes matches the oval guidelines as close as possible both in position and size.

Children will have no head immobilisation and the same instructions will be given to all of the included participants by an animated picture of a child speaking in their native language. Children younger than 24 months will be positioned on a parent’s lap, and instructions will be given to them to keep their heads steady.

DIVE exam will be performed without any optical correction, due to the methodology and goals of the study. Children wearing glasses will be asked to remove them at least 30 min before running the test, to simulate a patient with no previous optical correction.

The calibration procedure of the eye tracker (ET) will always be performed prior to test. Each child will be asked to fixate on a picture of an animal with associated sound, appearing at nine different locations across the screen, one at a time. The calibration procedure will be repeated until a good calibration has been reached, based on manufacturer’s recommendations. Children unable to achieve an acceptable calibration after three attempts will proceed with the test, since this is mostly due to poor visual function.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Age between 6 months and 14 years.

Visual fixation stable enough to allow attentive fixation on the Lang cube.

Assessments performed for all the following visual outcomes (although in some cases information may not be obtained): oculomotor control, ocular examination, visual acuity, ocular motility, red reflex, refraction under cycloplegia and funduscopy.

Informed consent signed by parents or guardians of the child, and assent by children older than 12 years of age (included as online supplementary file 1).

bmjopen-2019-033139supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

Exclusion criteria

Previous ocular, muscular or orbital surgery.

Bad general health state, which does not allow an examination with DIVE.

Children previously treated with optical correction, minor topic treatments or any therapy for amblyopia, will not be excluded.

Variables

Demographic information:

date of birth

date of assessment

gender

gestational age at birth

birth weight

perinatal adverse events

medical diseases

treatments

ethnicity

eye colour

II. Ophthalmic history:

amblyopia

patching

current optical correction

others

III. Monocular visual assessment:

visual fixation: quality, location and duration

smooth pursuit

saccadic performance: saccadic reaction time and accuracy

visual acuity, assessed with different optotypes depending on the age

stereoacuity

ocular alignment and ocular motility

binocular red reflex

anterior segment exam

refraction under cycloplegia

ophthalmoscopy

IV. Gaze positions throughout all DIVE test.

Outcomes

Outcomes related to the AI algorithm during the validation phase were:

True positives (TP)

True negatives (TN)

False positives (FP)

False negatives (FN)

Sensitivity=TP/(TP +FN)

Specificity=TN/(TN +FP)

Accuracy=(TP+TN)/(TP+TN+FP+FN)

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC)

They will be measured after the finalisation of the clinical part with the final database.

Participant timeline

All the participants will be enrolled from March 2019 to December 2019.

Sample size

For the training of the AI system, a minimum of 2000 patients will be recruited. We expect at least 40% of them to have normal visual development and at least 5% to be in each classification group with abnormal visual development. Since eyes will be used independently for the monocular examination, at least 4000 records will be available for training that part of the system. However, sample size will be adjusted along the recruitment, based on the classification performance of the model. Estimating sample size required to train a deep learning model is considered an impossible task, since it depends on many different aspects, which are unavailable at the beginning of the recruitment, such as the statistical features of the data.

For the validation phase, we will include a minimum of 200 patients from different age groups, with both normal visual development and a variety of visual pathologies.

Data collection

Participants will be recruited in at least five different hospitals. All the information from every patient will be collected in a database allocated in the DIVE devices.

Each participant will be given a code, which will be the only link between demographic information, visual assessment and visual examination with DIVE. Anonymised data sets of visual outcomes and demographic information, labelled by the ophthalmologists, will be automatically uploaded to a non-publically available repository in Google Cloud Storage, through which the Coordinating Unit will have instant access to the data.

All the information gathered will be treated according to the current regulations of personal data protection. All the parents or guardians from the patients will sign a written informed consent, and everyone in charge of handling the data will sign an non-disclosure agreement (NDA).

Data monitoring

Before collected data is used to train the neural network, it will go through a thorough auditing stage. This data auditing stage is designed to guarantee that the protocol is being followed consistently and that all collected data is free of errors. It consists of an automatic analysis performed with custom Python code, manual revision of automatically detected potential issues in collected data and manual random revision of patient data from every recruitment centre.

During this stage, will also compute statistics on the collected data to have real-time information on the number of recruited patients, predominant age groups, detected visual pathologies and quality of the collected data. This information is used to guide the recruitment process in order to obtain a balanced and varied data set.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in any part of the design of the study.

Statistical analysis

Study success will be predefined based on sensitivity, specificity and AUC outcomes of the AI system during the validation phase. Sensitivity ranges from 0.6 to 0.9 in most of the vision screening programmes aiming to detect amblyopia risk factors, using a combination of clinical tests (ie, visual acuity, stereoacuity and ocular alignment), with specificity ranging from 0.86 to 0.94.21 However, most of the studies have been performed on children aged at least 3 years. Screening programmes based on digital devices, such as autorefractometers, have shown slightly lower accuracy, with sensitivity of 0.88 and specificity of 0.58 for children aged 3 to 5 years, and 0.80 and 0.41, respectively, for children younger than 3 years.19

The hypotheses of interest will be:

H0: p<p0 and HA: p≥p0, where p is the sensitivity or specificity of the AI system. For children older than 3 years, p0 will be set at 0.90 for sensitivity and 0.70 for specificity, and for children younger than 3 years, p0 will be 0.85 and 0.50, respectively.

One-sided testing will be used, with a 2.5% Type I error.

Values of AUC will be used to assess the overall diagnostic accuracy of the AI algorithm. Outcomes, ranging from 0 to 1, will be interpreted using well-established decision thresholds: An AUC lower or equal to 0.5 suggests no discrimination, 0.5 to 0.7 is considered low discrimination, 0.7 to 0.8 acceptable, 0.8 to 0.9 excellent and more than 0.9 is considered outstanding.22

Secondary objectives will be analysed by descriptive outcomes (ie, mean, SD, 95% CIs and z-scores) and normal distribution plots. Continuous variables will be compared using Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for non-normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk’s test, p<0.05), and categorical variables by means of Pearson’s or Fisher’s exact tests. Multivariate analysis will be done using linear or logistic regression models.

Ethics and dissemination

The study will be conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice. All the study has been designed following the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki from 1964, reviewed by the WHO later in 2000 and the Spanish Data Protection Act (Organic Law 3/2018).

Patient data will be anonymised, that is, personal information from patients will not be included in the data set.

Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and disseminated at international scientific meetings.

Discussion

Vision screening in childhood is a cost-effective way to detect visual disorders and has been recommended for children of all ages by most Paediatric Ophthalmology scientific institutions.17 However, examiners in charge of it face important barriers, including limited training to perform it efficiently, lack of accurate screening tools and poor collaboration from children younger than 3 years.16

With this project, we aim to develop an easy-to-use system to perform a fast vision screening in children from 6 months of age. The system will include artificial intelligence algorithms to overcome the difficulties of interpreting the outcomes of a comprehensive visual assessment.

The main strength of this study lies in the large sample of children involved and its potential to include a heterogeneous sample of participants, in terms of age, ethnicity, cultural background and geographical location. It will ensure the external validity of the trained neural networks in any different setting. The main limitation is related to the number of ophthalmologists recruiting children and running the clinical protocol. In order to avoid this source of bias, the Coordinating Unit will provide all the researchers with very exhaustive training programme and documentation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: VP and MO were involved in the conception and design of the study, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. The clinical protocol was designed by EP, TP, OC, IG, JP, MR and MC. MO, BM, DG, AF, IA, AA and XP designed the DIVE protocol and monitoring system. All the authors contributed to further drafts, reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This work is funded by Huawei Technologies Company. Instituto de Investigacion Sanitaria (IIS) Aragón.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragón (CEICA) on January 2019 (Code PI18/346).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:614–8. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bourne RRA, Flaxman SR, Braithwaite T, et al. Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e888–97. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30293-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bourne RRA, Stevens GA, White RA, et al. Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis. The Lancet Global Health 2013;1:e339–49. 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70113-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dale N, Salt A. Early support developmental Journal for children with visual impairment: the case for a new developmental framework for early intervention. Child Care Health Dev 2007;33:684–90. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00798.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization Blindness and deafness Unit & International Agency for the prevention of blindness. Preventing blindness in children: report of WHO/IAPB scientific meeting. Hyderabad, India. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6. VISION The Right to Sight - IAPB, 2020. Available: https://www.iapb.org/vision-2020/ [Accessed 14 Mar 2019].

- 7. Gilbert C, Foster A. Childhood blindness in the context of vision 2020-the right to sight. Bull World Health Organ 2001;79:227–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Resnikoff S, et al. Global magnitude of visual impairment caused by uncorrected refractive errors in 2004. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:63–70. 10.2471/BLT.07.041210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen M, Wu A, Zhang L, et al. The increasing prevalence of myopia and high myopia among high school students in Fenghua City, eastern China: a 15-year population-based survey. BMC Ophthalmol 2018;18 10.1186/s12886-018-0829-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Doshi NR, Rodriguez MLF. Amblyopia 2007. [PubMed]

- 11. McKean-Cowdin R, Cotter SA, Tarczy-Hornoch K, et al. Prevalence of amblyopia or strabismus in Asian and non-Hispanic white preschool children: multi-ethnic pediatric eye disease study. Ophthalmology 2013;120:2117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Honavar SG. Pediatric eye screening - Why, when, and how. Indian J Ophthalmol 2018;66:889 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1030_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Vision screening in children aged 6 months to 5 years. JAMA 2017;318:836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holmes JM, et al. The amblyopia treatment study visual acuity testing protocol. Arch Ophthal 2001;119:1345–53. 10.1001/archopht.119.9.1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marsh-Tootle WL, Funkhouser E, Frazier MG, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and environment: what primary care providers say about pre-school vision screening. Optom Vis Sci 2010;87:104–11. 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181cc8d7c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. L. Couser N, Q. Esmail F, K. Hutchinson A, et al. Vision Screening in the Pediatrician’s Office. Open J Ophthalmol 2012;02:9–13. 10.4236/ojoph.2012.22003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wallace DK, Morse CL, Melia M, et al. Pediatric eye evaluations preferred practice Pattern®: I. vision screening in the primary care and community setting; II. comprehensive ophthalmic examination. Ophthalmology 2018;125:P184–227. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Wallace IF, et al. Vision screening in children ages 6 months to 5 years. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) 2017. [PubMed]

- 19. Kemper AR, Keating LM, Jackson JL, et al. Comparison of monocular Autorefraction to comprehensive eye examinations in preschool-aged and younger children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:435 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Fauw J, Ledsam JR, Romera-Paredes B, et al. Clinically applicable deep learning for diagnosis and referral in retinal disease. Nat Med 2018;24:1342–50. 10.1038/s41591-018-0107-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Wallace IF. Vision screening in children ages 6 months to 5 years. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mandrekar JN. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1315–6. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ec173d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033139supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)