Abstract

Introduction

People with depression often experience disabilities that limit their social and physical capacity, daily function, and quality of life. Depressive symptoms and their implications on daily activities are often measured retrospectively using subjective measurement tools. Recently, more objective and accurate electronic data collection methods have been used to describe the daily life of people with depressive disorders. The results, however, have not yet been systematically reviewed. We aim to provide a knowledge basis for the use of tracking technologies in examining life-space mobility among adults with depression and those with anxiety as a comorbidity.

Methods and analysis

A systematic review with a narrative approach for different types of study design will be conducted. The following databases will be used to gather data from 1994 to the present: MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, Embase, Cochrane Library, Scopus, Web of Science, Health Technology Assessment Database and IEEE Xplore. The study selection will follow the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols. Methodological appraisal of studies will be performed using the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool as well as the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool for randomised controlled trials. A narrative synthesis of all included studies will be conducted.

Ethics and dissemination

Because there will be no human involvement in the actual systematic review, no ethical approval will be required. The results will be disseminated in a peer-reviewed journal and in a conference presentation.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42019127102.

Keywords: life space, mobility, depression, anxiety, tracking

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this systematic review will be the first to combine knowledge about existing tracking technology used to explore life-space mobility among people with depression and/or anxiety disorder in real-time and in real-world urban settings.

Methods used in this review will be reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols.

This review protocol increases the transparency of the review process, improves the systematic approach, reduces bias and informs the reviewers of the planned steps, thereby reducing the possibility of data manipulation.

The results of the review provide evidence on the current technology used in tracking studies that may identify knowledge gaps and lead to ideas for future studies.

We anticipate that there may be a large variety of tracking technologies and it could be difficult to draw clear conclusions, and will thus challenge the implications of the results for clinical practice.

Introduction

Depression is ranked as the single largest contributor to global disability.1 It has been estimated that about 6% of the world’s population suffer from depression.2 In 2015, depression contributed 7.5% of all years lived with disability.1 It is also a major contributor to suicide deaths, accounting for anywhere from half to two-thirds of suicide cases, making it one of the top 20 leading causes of death.1 Depression is associated with high treatment costs and limits productivity in communities due to associated long-term outcomes such as hypertension, diabetes, emotional problems and high rates of disability, compared with other chronic diseases.1 3 4 In 2010, it was estimated that the economic burden of depression in the USA was US$210.5 billion.5

People with depression may experience various mental health effects, including persistently feeling low, loss of interest and enjoyment, anxiety as a comorbidity,6 and a range of emotional, cognitive, physical and behavioural symptoms.7 Different symptoms along with daily problems that a person experiences may increase their reluctance to engage in daily social activities and work.8 Among other problems, almost two-thirds of individuals with depressive disorder have clinical anxiety as a comorbidity.9 In the USA, the prevalence of anxiety in people with depression has been reported at 57.5%.10 It has also been found in a European cohort study that adults with depression and anxiety disorder had lower level of physical function compared with those without these conditions. In this study physical function referred to limitations in performing normal activities of daily living and mobility, such as performing personal hygiene activities, eating or preparing meals, and doing housework.8 In institutional settings, apathy and depressive symptoms have been found to have the greatest potential to limit life space among older people.11 Life space refers to the area where a person moves through in daily life, extending from within their home to a wider geographical area.12

The association between depressive symptoms and individual life space has been reported in previous studies.12 13 Life-space mobility is a measurement of the space through which a person moves over a specific period of time.12 It is a means to view an individual’s functioning and participation in real-world situations as it measures their ability to walk, use public transportation or drive a car.14 15 It is assumed that a larger life-space mobility provides more opportunities for an individual to engage with society,16 while a restricted life-space mobility may reflect limited access to societal amenities.17 18 Al Snih et al 13 showed that a high number of depressive symptoms is one of the contributing factors to and is significantly associated with a lower level of life-space mobility. Other studies have shown that a restricted life space may be related to negative health outcomes, such as disability and cognition.14 19–21 Boyle et al,22 in their prospective observational cohort study, further indicated that a restricted life space is associated with a higher risk of mortality, while Cacioppo23 further proposed that a larger life space may contribute to the effective functioning of physiological systems and therefore lead to better physical health outcomes. Self-reported measurements have often been used to assess life-space mobility, yet although they can be helpful they tend to overestimate true mobility and underestimate sedentary time.24 25 Therefore, more accurate and objective methods to determine human mobility are needed.26

Understanding of the association between objective behavioural features, for example, physical activity, biometrics, physical state and social behaviour, and depressive mood symptoms has provided new opportunities for using mobile applications and wearable devices to monitor depression and other affective disorders.27 It has been proposed that technological devices can easily and objectively provide a way to monitor the activity of people with these illnesses and could serve as a digital marker of mood symptoms.28 29 We found two reviews that assessed individual mobility using technological devices in patients with mental disorders. Burton et al 30, in their systematic review, investigated the associations between objectively measured physical activity and depression using digital actigraphy in patients with depression where digital actigraphy is an objective measurement of activity using body-worn accelerometers.31 The authors identified 19 eligible papers (16 studies), including 412 patients where actigraphy was used to measure activity levels and sleep. Based on the case–control studies, it was found that patients with depression engage in less daytime activity, while the longitudinal studies showed a moderate increase in daytime activity and a reduction in night-time activity over the course of drug and conventional treatment. The researchers concluded that actigraphy is a potentially valuable source of additional data on patients with depression, although there should be more clear guidelines on the use of actigraphy in studies of patients with depression. Another systematic review, by Rohani et al, provides an overview of the correlations between objective behavioural features and depressive mood symptoms using mobile and wearable devices.27 In their review, they found 85 unique objective behavioural features covering 17 various sensor data inputs, which were divided into seven categories in studies. They found several features that had statistically significant and consistent correlation directionality with mood assessment, such as the amount of homestay, sleep duration and vigorous activity. On the other hand, other features showed discrepancies in directionality across the studies, such as time spent between locations. Like Burton et al, Rohani et al 27 30 concluded that, due to statistically significant correlations between objective behavioural features collected via mobile and wearable devices and depressive mood symptoms, continuous and everyday monitoring of behavioural aspects in affective disorders could be a promising supplementary objective measure to estimate depressive mood symptoms.

However, there remains a lack of knowledge on how mobility patterns and habits of people with depression during the course of their illness can be measured using different technological devices in order to gain more understanding of these people’s daily life. Rohani et al 27 suggested that a standardised data collection method for physical activity and mobility features is needed, since as found in their review there were limitations associated with different technologies used to measure mobility data. Therefore, there is a need for wider knowledge on how different technological devices can be used to collect data and how they can be used as digital markers of life-space mobility in real-life community settings.30 This would result in better opportunities to tailor treatment plans according to individuals’ daily functioning and habits. Such knowledge can also provide ideas on the future development needs of technological devices. However, to do this, we first need more knowledge on the tracking methods available and how these methods are used on a daily basis, keeping in mind their possible benefits and concerns.

Aim and research questions

The overall aim of this systematic review is to describe the tracking technologies used in understanding life-space mobility among adults with depression. The review questions are as follows: (1) What types of technology have been used in tracking life-space mobility among people with depression? (2) How has the technology been used in tracking life-space mobility among people with depression? (3) What are the outcome measurements used in tracking life-space mobility among people with depression?

This systematic review protocol is designed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P).32 This guideline is useful because it focuses on ways in which authors can ensure transparent and complete reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses and facilitate the development and reporting of systematic review protocols.33 The protocol has been registered with PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews).

Methods and analysis

Design

A systematic review with narrative synthesis will be used to search, appraise and synthesise empirical evidence. This approach is useful for our purpose because narrative synthesis focuses on a wide range of questions, not only those relating to the effectiveness of a particular intervention.34

Eligibility criteria

The PICO (patient, intervention, comparison, outcome) approach was used to specify eligibility of studies.35

Population

Articles should include adult participants of both genders and who have depressive symptoms or are diagnosed with depression. Depression is identified by signs and symptoms, either self-reported or identified using specific assessment instruments such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Diagnosis should be verified using specific diagnostic criteria (eg, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, International Classification of Diseases). Articles involving a person with anxiety as a comorbidity will also be included since there is a high prevalence of anxiety as a comorbidity in depression.10 We will exclude articles where subjects are diagnosed with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, learning disabilities or other serious cognitive disorders. Articles involving only children or adolescents will also be excluded.

Intervention

All articles that study any type of tracking device will be included. Tracking technology can include mobile or wireless health devices, which are portable internal and wearable sensors used to monitor health.36 Other devices can include accelerometers, gyroscopes, vector magnetometers, goniometers, piezoelectric, textile pressure sensors, electromyography, tilt/bend sensors and the global positioning system, which are able to measure the type, quantity and quality of daily activity, movement and balance.36 Articles on the methods used to track people’s movement or activity without the use of technology, such as written diaries or questionnaires, will not be included.

Outcomes

The main outcome of the study will be the type of tracking device used. The secondary outcomes are how the technology has been used and the outcome measurements used in tracking life-space mobility among people with depression.

Study design

Articles using any type of research design will be included as long as the study includes any type of tracking device.

Other

Articles will be limited to peer-reviewed, published full-text articles. There will be no restriction with regard to language. Theoretical papers, statistical reviews, books or book chapters, letters, dissertations, editorials, and study protocols will be excluded.

Data sources

A comprehensive literature search with no specific year limits will be conducted. The following electronic databases will be searched: MEDLINE (via EBSCOhost), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Complete, PsycINFO, Embase, Cochrane Library (academic database for medicine and health science and nursing), Scopus, Web of Science (academic database across all scientific and technical disciplines, ranging from medicine and social sciences to arts and humanities),37 Health Technology Assessment Database (database for health technology) and IEEE Xplore (academic database for technology and engineering). These databases will be used as these allow wide literature search in various disciplines that are related to our review topic. The reference lists of the selected papers will also be screened for additional studies.

Search strategy

The search strategy will be elaborated on and implemented prior to the study selection. We will use the PRISMA-P checklist for guidance.32 First, controlled vocabulary thesaurus (such as medical subject heading terms, CINAHL headings, PsycINFO thesaurus) and their keywords will be verified in each database. The search terms will be combined using the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR”. Second, the following string of search terms will be used to ensure a broad coverage of published studies: (“depression” OR “affective disorder*” OR “anxiety” OR “anxiety disorder*” OR “mental health” OR “mood disorder*” OR “unipolar” OR “mental disorder*“) AND (“tracking” OR “tracking device*” OR “tracking technology*” OR “wearable device*” OR “wearable sensor*” OR “wearable technology*” OR “technology*“) AND (“mobility” OR “life space”). Advice on using keywords to search for studies will be sought from a faculty librarian. An example of a database and the search terms used is presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Example of database and search terms used

| Database | Search terms | References, n |

| Scopus | ((ALL (tracking) OR ALL (“tracking device*”) OR ALL (“tracking technology*”) OR ALL (“wearable device*”) OR ALL (“wearable sensor*”) OR ALL (“wearable technology*”) OR ALL (“technology*”))) AND ((ALL (mobility) OR ALL (“life-space”))) AND ((ALL (depression) OR ALL (“affective disorder*”) OR ALL (anxiety) OR ALL (“anxiety disorder*”) OR ALL (“mental health”) OR ALL (“mood disorder*”) OR ALL (unipolar) OR ALL (“mental disorder*”))) |

Analysis

Data management

EndNote will be used to efficiently manage the retrieved records, and will be helpful in documenting the process, streamlining document management, and providing reference lists from reports and journal papers. EndNote will also be used to manage duplicate papers and ensure these papers are not treated as separate studies.38

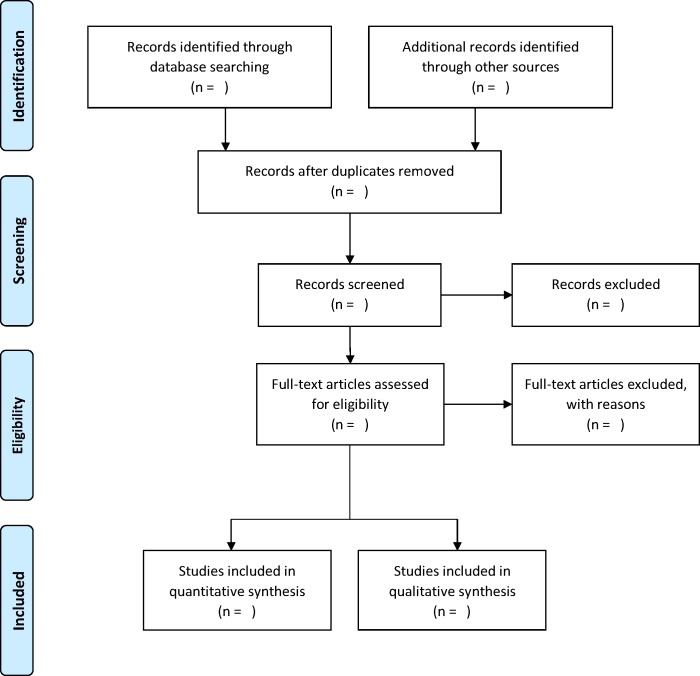

Selection process

The study selection process consists of four steps (figure 1).29 First, titles and abstracts will be independently assessed by two authors (MHC, MV) according to the inclusion criteria. Second, the abstract of the papers will be screened for relevance and eligibility, again by the same two authors (MHC, MV). Third, the full texts of the selected articles will be screened by two authors (MHC, MV) according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In case of any discrepancy on decisions made by the two authors, the paper will be discussed with another author (SFL). Papers that do not meet the inclusion criteria will be rejected, and the reason for exclusion (ie, irrelevance or failure to meet the inclusion criteria) will be recorded to increase transparency in the selection process. Fourth, the full texts of the studies that meet the inclusion criteria will be obtained for further detailed assessment. The reference lists of the selected papers will also be screened and checked for additional papers that meet the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram outlining the review process. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols.

Data collection process

To answer the review questions, specific tables will be created to collect data from selected papers. Data will be extracted by one author (MHC) and will be reviewed for completeness and accuracy by another author (MV).

Data items

Characteristics of the studies and the population

To describe the characteristics of each study, the following data will be collected: name(s) of the author(s), year of publication, country where the study was conducted, purpose of the study, setting, type of study, study design and population/sample size (response rate).

Intervention

Details of the tracking technology used will be extracted: tracking technology used, characteristics of the tracking technology, administrator, length of tracking period and possible challenges in using the tracking technology.

Outcomes

The following data related to participants’ daily activity and community participation will be collected: specific outcomes, instruments used to measure the outcomes, the number of items and scoring for the instruments (total scale/subscales), and validity and reliability. Further, the following data will be extracted to describe participants’ daily activity and community participation patterns based on the outcome measures used: number of activities per day, time of day, type of activity, destination of the activity and duration of the activity.

Data extraction

To describe the characteristics of the included studies and to answer each review question, data from the selected papers will be extracted by one author (MHC) and inputted into predesigned tables; the process will be validated by MV.

Data synthesis

Initial descriptive synthesis will be conducted by tabulating details on study type, interventions, number of participants and an overview of participant characteristics, to form a clear descriptive summary of the included studies.38 The descriptive process will be conducted explicitly and rigorously, and decisions on how to group and tabulate data will be made based on the protocol and review questions.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Appraisal of risk or methodological quality of the primary studies is an important step in a systematic review as it helps decide whether the results of the study are reliable. During the review process, studies will be deemed to have risk of bias if they fail to make objective decision on study design and on the level of quality required.39

The quality of each study will be appraised using the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool (CCAT).

CCAT was designed based on a review of 44 critical appraisal tools across all research designs.40 The tool consists of eight categories (preliminaries, introduction, design, sampling, data collection, ethical matters, results and discussion) divided into 22 items, which are further divided into 98 item descriptors.40 The combination of categories, items and item descriptors allows for a wide range of qualitative and quantitative health research to be appraised using one tool.40–42 The scoring of the tool provides a combination of subjective and objective assessments. Each category is scored from 0 (the lowest score) to 5 (the highest score). The total score given to a paper is expressed in percentage, dividing the total by 40.

The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials will also be used to assess the quality of randomised trial articles included in the review.43 Each area to be assessed will be rated as ‘low risk’, ‘high risk’ or ‘unclear risk’ of bias. The overall quality of an article using a randomised controlled trial design will be rated as ‘good’, ‘fair’ or ‘poor’.

Patient and public involvement

Patients will not be directly involved in the design of this study. As this is a protocol for a systematic review and no participant recruitment will take place, their involvement in the recruitment as well as dissemination of findings to participants will not be applicable.

Amendments

Any amendments to this protocol will be documented.

Ethics and dissemination

Because there will be no data collection involving human subjects in the actual systematic review, no ethical approval will be required. The results will be disseminated in a peer-reviewed journal and in a conference presentation.

Planned start and end date

The review is planned to start on 1 December 2019 and end on 30 November 2020.

Discussion

The proposed review has a number of strengths. First, this systematic review protocol increases the transparency of the review process, improves the systematic approach, reduces bias and opens the planned steps to reviewers, thereby reducing the possibility of data manipulation. Second, this review will provide evidence on the use of tracking technologies to study the life-space mobility of adults with depression and/or anxiety disorder, which may provide new opportunities for further studies. Third, this review will be the first to combine knowledge on existing tracking technology as a tool used to explore the life-space mobility of people with depression in real-time and real-world urban settings. However, we anticipate that there is a large variety of tracking technologies and it could be difficult to draw clear conclusions, and will thus challenge the implications of the results for clinical practice.

In conclusion, this systematic review will provide the best example of the use of tracking technologies in studying the life-space mobility of adults with depression and/or anxiety disorder. The results of the review will inform and guide future studies on describing the life-space mobility of people with depression in real-time and in real-world urban settings in Hong Kong. Further, the results will provide insights into rehabilitation services and policies tailored to individuals’ concerns and needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers of the manuscript for their constructive feedback, and the faculty librarian of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University for the literature search.

Footnotes

Contributors: MV initiated and designed the review. The manuscript protocol was drafted by MHC and reviewed by MV and SFL. The search strategy was developed by all the authors and will be performed by MHC and MV, who will also independently screen potential articles, extract data from the included studies, assess the risk of bias and complete the data synthesis. SFL will arbitrate in cases of disagreement and ensure the absence of errors. All authors approved the publication of the protocol.

Funding: The review is supported by the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Funding has been granted by the University of Turku, Finland (project number: 26003424).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Organization WH Depression and other common mental disorders global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health 2013;34:119–38. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. . The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA 1989;262:914–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, et al. . Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:11–19. 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950130011002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greenberg PE, Fournier A-A, Sisitsky T, et al. . The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:155–62. 10.4088/JCP.14m09298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization Depression and other common mental disorders global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Collaborating Centre For Mental Health The treatment and management of depression in adults (updated edition). London: The British Psychological Society, The Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stegenga BT, Nazareth I, Torres-González F, et al. . Depression, anxiety and physical function: exploring the strength of causality. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:e25 10.1136/jech.2010.128371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. The Lancet 2018;392:2299–312. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31948-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, Wang PS. Prevalence, comorbidity, and service utilization for mood disorders in the United States at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2007;3:137–58. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jansen C-P, Diegelmann M, Schnabel E-L, et al. . Life-space and movement behavior in nursing home residents: results of a new sensor-based assessment and associated factors. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:36 10.1186/s12877-017-0430-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peel C, Sawyer Baker P, Roth DL, et al. . Assessing mobility in older adults: the UAB study of aging Life-Space assessment. Phys Ther 2005;85:1008–19. 10.1093/ptj/85.10.1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Al Snih S, Peek KM, Sawyer P, et al. . Life-space mobility in Mexican Americans aged 75 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:532–7. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03822.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baker PS, Bodner EV, Allman RM. Measuring life-space mobility in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1610–4. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stalvey BT, Owsley C, Sloane ME, et al. . The life space questionnaire: a measure of the extent of mobility of older adults. J Appl Gerontol 1999;18:460–78. 10.1177/073346489901800404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kono A, Kai I, Sakato C, et al. . Frequency of going outdoors: a predictor of functional and psychosocial change among ambulatory frail elders living at home. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004;59:M275–80. 10.1093/gerona/59.3.M275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brown CJ, Roth DL, Allman RM, et al. . Trajectories of life-Space mobility after hospitalization. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:372–8. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-6-200903170-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosso AL, Taylor JA, Tabb LP, et al. . Mobility, disability, and social engagement in older adults. J Aging Health 2013;25:617–37. 10.1177/0898264313482489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murata C, Kondo T, Tamakoshi K, et al. . Factors associated with life space among community-living rural elders in Japan. Public Health Nurs 2006;23:324–31. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00568.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, et al. . Correlates of life space in a volunteer cohort of older adults. Exp Aging Res 2007;33:77–93. 10.1080/03610730601006420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Allman RM, Sawyer P, Roseman JM. The UAB study of aging: background and insights into life-space mobility among older Americans in rural and urban settings. Aging health 2006;2:417–29. 10.2217/1745509X.2.3.417 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, et al. . Association between life space and risk of mortality in advanced age. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1925–30. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03058.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cacioppo JT. Social neuroscience: autonomic, neuroendocrine, and immune responses to stress. Psychophysiology 1994;31:113–28. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb01032.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chinapaw MJM, Slootmaker SM, Schuit AJ, et al. . Reliability and validity of the activity questionnaire for adults and adolescents (AQuAA). BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:58 10.1186/1471-2288-9-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tudor-Locke CE, Myers AM, Myers E. Challenges and opportunities for measuring physical activity in sedentary adults. Sports Med 2001;31:91–100. 10.2165/00007256-200131020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Madan A, Moturu ST, Lazer D. Social sensing: obesity, unhealthy eating and exercise in face-to-face networks. Proceedings of Wireless Health, 2010:104–10. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rohani DA, Faurholt-Jepsen M, Kessing LV, et al. . Correlations between objective behavioral features collected from mobile and wearable devices and depressive mood symptoms in patients with affective disorders: systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e165 10.2196/mhealth.9691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mohr DC, Zhang M, Schueller SM. Personal sensing: understanding mental health using ubiquitous sensors and machine learning. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2017;13:23–47. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-044949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Afsaneh D, Jun Ki M, Jason W. Detection of behavior change in people with depression, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burton C, McKinstry B, Szentagotai Tătar A, et al. . Activity monitoring in patients with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2013;145:21–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matthews CE, Hagströmer M, Pober DM, et al. . Best practices for using physical activity monitors in population-based research. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:S68–76. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182399e5b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods programme, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eriksen MB, Frandsen TF. The impact of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: a systematic review. Jmla 2018;106:420–31. 10.5195/JMLA.2018.345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dobkin BH, Dorsch A. The promise of mHealth: daily activity monitoring and outcome assessments by wearable sensors. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2011;25:788–98. 10.1177/1545968311425908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Elsevier Scopus 2018. Available: https://www.elsevier.com/solutions/scopus [Accessed 10 Jan 2019].

- 38. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare. York, UK: York Publishing Services Ltd, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Seehra J, Pandis N, Koletsi D, et al. . Use of quality assessment tools in systematic reviews was varied and inconsistent. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;69:179–84. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Crowe M, Sheppard L. A review of critical appraisal tools show they lack rigor: Alternative tool structure is proposed. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:79–89. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Crowe M, Sheppard L. A general critical appraisal tool: an evaluation of construct validity. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:1505–16. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Crowe M, Sheppard L, Campbell A. Reliability analysis for a proposed critical appraisal tool demonstrated value for diverse research designs. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:375–83. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. . The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.