Abstract

Introduction

One potential stressor that can affect preimplantation and postimplantation embryonic growth after in vitro fertilisation (IVF) is the pH of the human embryo culture medium, but no evidence exists to indicate which pH level is optimal for IVF. Based on anecdotal evidence or mouse models, culture media manufacturers recommend a pH range of 7.2 to 7.4, and IVF laboratories routinely use a pH range of 7.25 to 7.3. Given the lack of randomised trials evaluating the effect of pH on live birth rate after IVF, this trial examines the effect of three different pH levels on the live birth rate.

Methods and analysis

This multicentre randomised trial will involve centres specialised in IVF in Egypt. Eligible couples for intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) will be randomised for embryo culture at pH 7.2, 7.3 or 7.4. The study is designed to detect 10 percentage points difference in live birth rate between the best and worst performing media with 93% power at a 1% significance level. The primary outcome is the rate of live birth (delivery of one or more viable infants beyond the 20th week of gestation) after ICSI. Secondary clinical outcomes include biochemical pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, ongoing pregnancy, miscarriage, preterm births, birth weight, stillbirth, congenital malformation and cumulative live birth (within 1 year from randomisation). Embryo development outcomes include fertilisation, blastocyst formation and quality, and embryo cryopreservation and utilisation.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Boards of the participating centres. Eligible women will sign a written informed consent before enrolment. This study has an independent data monitoring and safety committee comprised international experts in trial design and in vitro culture. No plan exists to disseminate results to participants or health communities, except for the independent monitoring and safety committee of the trial.

Trial registration number

Keywords: embryo culture, pH level, culture media, blastocyst formation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study is a randomised controlled trial, which reduces the possibility of bias.

The study has an independent data monitoring committee with full access to the data.

Limitations of this study include the inclusion of only intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles because ICSI is the preferred method of insemination in the participating centres and that the calculation of blastocyst formation rate is based on an assumption for cleavage-stage transfer cycles.

The embryologists will be aware of the pH level as the study is being conducted.

Background

Assisted reproductive techniques result in a cumulative live birth rate of around 65% within six cycles of in vitro fertilisation (IVF),1 which is relatively suboptimal. In addition, IVF has been associated with adverse perinatal outcomes, such as preterm birth and low birth weight babies compared with the in vivo conception.2 These adverse consequences can be due to a range of factors including patient demographics, ovarian stimulation and the culture system. In relation to embryo culture conditions, over 200 variables have been identified as having effects on cycle outcome.3 One element that may influence embryo development in vitro is the culture medium pH, which thus far has been determined by manufacturers of culture media without recourse to a well-powered randomised clinical trial.4 pH levels are potential stressors that vary between media brands and from batch-to-batch depending on the levels of bicarbonate in the culture media and of CO2 in incubators.5 Hence, pH levels can vary between incubators within a laboratory. Recommendations for the frequency of pH measurement for embryo culture vary from daily to monthly.4

The intracellular pH (pHi) of oocytes and embryos is modulated by the extracellular pH (pHe),6 which is affected by the culture conditions, including the concentrations of bicarbonate, protein and amino acids in culture media, and of the CO2 in incubators.7 The mechanism of pHi in oocytes and embryos is complex, regulating enzymatic activity, cell division and differentiation, protein synthesis, metabolism, mitochondrial function, cytoskeletal regulation, and microtubule dynamics.7 8 Drifts in pHe translate into changes in pHi, which can adversely affect cell function if compensatory mechanisms fail to restore pHi to a safe level.8 These compensatory mechanisms include an active exchange among Na+, HCO3 –/Cl– and Na+/H+ to maintain pHi between 7 and 7.3.5 8 Oocytes that have been denuded of their surrounding corona and cumulus cells prior to insemination via ICSI, as well as vitrified-warmed embryos, lack robust compensatory mechanisms for maintenance of pHi; therefore, drastic differences between pHe and pHi in these cases can disrupt embryo development.9–11

That being said, the optimal pH level to support human embryo development in vitro is still undefined.4 9 12–15 Current recommendations are based on results derived using mouse models and/or literature from culture medium manufacturers. Theoretically, a wide range of pHe levels (7.0–7.5) could support human embryo development in vitro, but a narrower range of pHe levels (7.2–7.4) is used in clinical practice. This is because a more acidic pHe (≤7) can adversely affect the oocyte spindle, delaying or even blocking embryo development in vitro.4 Alkaline levels of pHe (≥7.5) can similarly harm oocytes and embryos.4 Although these reports of the effects of extreme pHe levels rely on animal models, underpowered studies or anecdotal beliefs, we have decided to limit our investigation to the range of pHe used in clinical practice (7.2–7.4) as the safer alternative. Despite the routine use of pHe 7.2–7.4 in clinical practice, there is no clear evidence as to whether there is a level within this range that could better support human embryo development to result in a live birth. The aim of this multicentre, randomised, clinical trial is to identify whether pHe 7.2, 7.3 or 7.4 results in an improved live birth rate after ICSI in order to investigate the potential for optimisation.

Methods and design

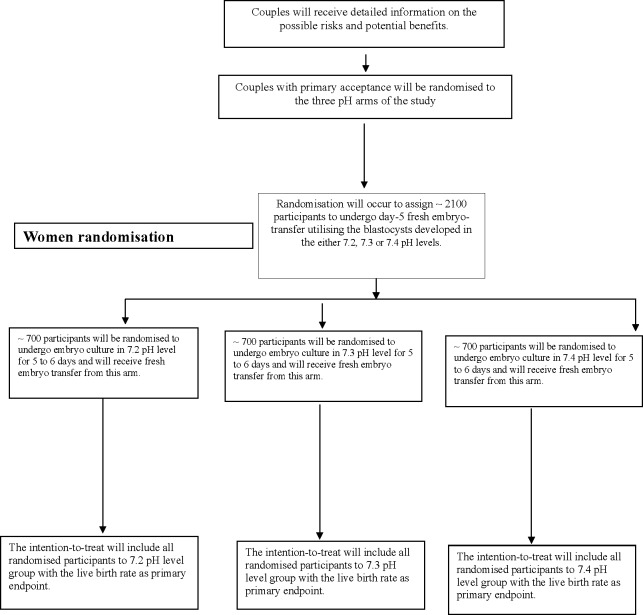

This is a protocol of a multicentre, randomised, triple-arm, triple-blind clinical trial (NCT02896777, registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov) that will compare the effect of three pH levels for human embryo culture in vitro on live birth after ICSI (figure 1). In this partially blind design, the clinicians, participants and outcome assessor will be unaware of the study arms, but the embryologists will be aware. This multicentre trial will involve private IVF facilities in Egypt (Ibnsina IVF Centre, Egyptian IVF-ET centre, Banon IVF Centre, Qena IVF Centre and Amshaj IVF Centre) which will all have the study protocol prior to enrolment of participants. If other IVF facilities join this trial before recruitment, this will be reported in the study.

Figure 1.

Trial plan for enrolment. pH trial plan for enrolment and outcomes – 7.2, 7.3 and 7.4 pH levels.

Intervention

In each arm of the trial, which will only include intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles, oocytes and embryos will undergo continuous culture from day 0 through day 5 or 6 without medium renewal. The oocytes and resulting embryos after ICSI will be cultured in either pHe 7.2±0.02 (‘Arm I’), pHe 7.3±0.02 (‘Arm II’) or pHe 7.4±0.02 (‘Arm III’).

Patient and public involvement

Patients have not been directly involved in the design, planning and conception of this trial.

Randomisation and masking

Using an online tool, participants will be randomised to the experimental arms with a 1:1:1 allocation ratio. The allocation sequence of participants will be generated using a permuted block randomisation of 3, 6 and 9 block sizes with unique identifiers in random order, stratified by trial site. Randomisation of participants and storage of the results in sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes will be performed by a secretary with no involvement in patient care, and the sealed envelopes will be provided to trial sites before enrolment of the first participant. Eligible participants will be allocated to the relevant arms on the day of maturation trigger and the allocation result will be communicated to the laboratory team. Participants, clinicians and outcome assessors for the clinical outcomes will be unaware of the allocation, whereas embryologists who will assess embryo development will be aware of the allocation.

Participants

The inclusion criteria include:

Women age of ≥18 to≤40.

Body mass index of ≤31.

Anticipated normal responder (≥5 antral follicle count or ≥5.4 pmol/L Anti-mullerian hormone (AMH)).

Women with ≥1 year of primary or secondary infertility.

Fresh ejaculated sperm of any count provided that there is ≥1% normal forms with any motile fraction.

Women undergoing their first ICSI cycle or their second ICSI cycle after a previously successful treatment.

Women with >7 mm endometrial thickness at the day of maturation trigger.

Women with no detected uterine abnormality on transvaginal ultrasound (eg, submucosal myomas, polyps or septa).

Women will be excluded if they have

Unilateral oophorectomy.

Abnormal karyotyping for them or their male partners.

History of repeated abortions or implantation failure;

Uncontrolled diabetes;

Liver or renal disease.

History of severe ovarian hyperstimulation.

History of malignancy or borderline pathology.

Endometriosis.

Plan for PGD-A.

Severe male factor includes surgical sperm retrieval or cryopreserved sperm.

PCOS, women with a history of severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), and cycles with agonist trigger or any patient with a plan for a ‘freeze-all’.

Stimulation protocol, oocyte retrieval and luteal phase support

Women will undergo controlled ovarian stimulation with agonist mid-luteal pituitary down-regulation (Decapeptyl 0.1 mg, Ferring, Switzerland) or antagonist (Cetrotide 0.25 mg, Merck Serono) protocols. Agonists will start on day 19–21 of the preceding cycle and will continue through the day of maturation trigger. In the antagonist protocol, women will start the antagonist on stimulation day 6 of the treatment cycle. Women will begin follicular stimulating hormone (rFSH; Gonal-F, Merck Serono) and human menopausal gonadotropin (HMG; Menogon, Ferring) at 150–300 IU with a 2:1 ratio from cycle day 2 through maturation, with dosage adjustment according to ovarian response. When three or more follicles measure ≥18 mm mean diameter on ultrasound, women will be given a 10 000 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) trigger shot (Choriomon, IBSA) for oocyte maturation. Oocyte retrieval will be performed 37 hours after the hCG trigger under transvaginal sonographic guidance. Follicular aspirates will be handled in HEPES-buffered medium (global HEPES, LifeGlobal, Canada) at 37°C using tube warmers. Luteal phase support will be achieved with intramuscular progesterone (100 mg/mL (Prontogest, IBSA)) once daily or vaginal pessaries (400 mg prontogest) twice daily, starting on day 1 after retrieval (‘day 1’) to 12 weeks of gestation, if a pregnancy is established.

Sperm preparation, oocyte denudation and ICSI

Semen samples will be processed using density gradient centrifugation16 (Puresperm, Nidacon, Sweden). The pellet will undergo once washing and incubation at room temperature in HEPES buffered medium (AllGrade Wash, LifeGlobal). Denudation of oocytes will occur immediately after collection in 40 IU hyaluronidase (LifeGlobal, Canada) diluted in Global HEPES using a 170 μm stripper (Cook, US). Metaphase II (MII) oocytes will undergo ICSI in Global HEPES medium under an inverted microscope as previously described.17

Incubator management and pH adjustment

We will use only humidified benchtop incubators for this study, involving Labo C-Top (Labotect, Germany), Minc-1000 (Cook, US), and AD-3100 (Astec, Japan). Each centre will use only one brand to account for incubators as a variable. It is possible that dry incubators such as ESCO (Esco Micro Pte. Ltd, Singapore) are used in some centres, but we note that our analysis will account for differences between centres by adjusting for trial sites. Incubators will undergo stringent control of temperature (36.9°C±0.1°C) by daily validation using certified thermometers. Incubator CO2 and O2 levels will be measured daily using a certified gas analyser to ensure that O2 measures 5%, and CO2 concentration is at the prespecified level to achieve the required pH. Well-trained persons across the sites will verify all measurements (temperature, CO2, O2 and pH levels). Incubators will be sterilised by 6% H2O2 every 4 weeks, along with the installation of a new set of inline filters (Green, Lifeglobal, CooperSurgical).18

A minimum of three incubators of a single brand within each facility is obligatory to represent the three pH arms: 7.2±0.02 pH level (incubator A), 7.3±0.02 pH level (incubator B) and 7.4±0.02 level (incubator C). The three incubators will undergo strict adjustments to maintain the required pH using a handheld blood gas analyser (Epoc Reader and Host; BGEM card US). Constant pH levels will be ensured by a two times per week measurement of pH using the blood gas analyser along with daily measurement of CO2 levels of incubators. Measurement of pH will occur following overnight incubation of 1 mL culture media in a central well dish covered with 0.4 mL oil. Before the opening of incubators, the handheld blood gas analyser (Epoc Reader and Host; BGEM card US) will be prepared for pH measurement as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, after switching on the device, the temperature will be set at 37 °C, sample type set as arterial and automatic calibration will be initiated. When the device is ready, 0.5 mL calibrated culture media will be aspirated using a 1 mL syringe attached to a wide calibre needle. The first droplet will be discarded and the remainder of the sample injected into the device, for the assessment of pH and partial pressures of CO2 and O2. In each laboratory, the partial pressures of CO2 and O2 will be compared with those on the incubator display. The pH levels will be measured with every new batch of culture media. Measurements of pH and CO2 across centres will be performed using the same brand of equipment with periodic calibration. To account for errors in measurement, one well-trained staff member will be assigned to measure the pH and double-check the CO2 level across trial sites.

Culture protocol and embryo scoring

Each culture dish (micro-droplet, Vitrolife) will hold 12×20 µL droplets of Global Total culture medium (Lifeglobal, CooperSurgical, USA) overlaid with 5 mL oil (NidOil, Nidacon). If there is a decision to change culture media at any time during the study, this will be performed at the same time across study sites. Dishes will be incubated overnight in the relevant incubator adjusted to the proper pH as per randomisation. After ICSI, the injected oocytes will undergo washing in culture medium followed by incubation from day 0 through day 5 or 6 in the relevant pH arm, except for a small portion of embryos transferred on day 3. The inseminated oocytes will undergo culture in groups of 3 each from days 0 to 5 or 6, with the removal of the unfertilised, abnormally fertilised or degenerated oocytes at fertilisation check. Two embryologists will perform the fertilisation check and embryo grading on days 1, 2, 3 and 5 of culture as per the Istanbul Consensus.19 All laboratories will vitrify embryos no earlier than day 5. Embryos will be suitable for transfer or vitrification on day 5 provided they are graded 3 1 1 as per the Istanbul Consensus.19 Images of embryos utilised for transfer or cryopreservation will be recorded in the patient file. All the images from all centres will undergo blind grading by two independent, experienced embryologists.

Embryo transfer

One to two embryos will be transferred per cycle. Women with a reduced uterine cavity or previous preterm birth will receive only one embryo. Trial sites will transfer blastocysts on day 5 except for one participating site that will transfer embryos on day 3. This issue will be accounted for by adjusting the analysis by the trial site. Embryos will be transferred under sonographic guidance using the Sydney IVF Transfer Set (Cook, US) as per the standard transfer protocol in each site. Any remaining utilisable embryos will be vitrified for transfer in subsequent cycles as we plan to monitor the cumulative live birth rate from fresh and vitrified-warmed transfers within 1 year from randomisation. Women will test the level of serum hCG for biochemical pregnancy 14 days after oocyte retrieval and will confirm clinical pregnancy at ≥week 7 of gestation by detection of intrauterine sacs with a heartbeat on the ultrasound.

Outcome measures

Each outcome will be calculated including all randomised participants in the arms to which they were allocated, with the exception of implantation rate, which will be interpreted cautiously due to concerns over its validity as a measure of treatment effect, and perinatal outcomes, which by definition are only available in the subset of participants achieving live birth. This study will adopt the definitions of outcomes included in a forthcoming core outcome set for infertility trials20 where appropriate. This outcome set was developed by means of an international consensus process involving clinicians, clinical scientists, patients and researchers.

Primary outcome

Live birth (delivery of one or more viable infants beyond the 20th week of gestation).

Secondary outcomes

All secondary outcomes will be cautiously reported as statistical significance has limited meaning in the context of a plurality of tests.

Biochemical pregnancy (positive βhCG ≥10 IU/L at 14 days after egg retrieval).

Clinical pregnancy (registered sacs with a heartbeat on ultrasound >7th week of gestation).

Ongoing pregnancy (continued viable pregnancy >20th week of gestation).

Miscarriage (loss of a clinical pregnancy ≤20th week of gestation).

Term live birth (ie, delivery of one or more viable infants ≥37 weeks of gestation).

Preterm birth (delivery of one or more viable infants <37th week of gestation).

Very preterm birth (delivery of one or more viable infants <32nd week of gestation).

Low birth weight babies (babies weighing <2500 g within 24 hours of delivery)

Congenital malformation (delivery of congenitally malformed babies).

Stillbirth (delivery of nonviable babies >20 weeks of gestation).

Cumulative live birth (registered viable neonates after one fresh plus one vitrified-warmed embryo transfer within 1 year of randomisation).

Fertilisation (presence of two pronuclei 17±1 hours after ICSI).

Embryo cleavage (cleaved embryos per fertilised oocyte).

Top-quality embryos on day 3 (7–8 cells with appropriate sizes blastomeres and <10% fragmentation by volume).

Blastocyst formation on day 5 or 6 (formed blastocysts per fertilised oocyte).

Top-quality blastocyst on day 5 (rounded and dense inner cell mass with many trophectodermal cells creating a connected zone and a blastocoel >100% by volume; ≥3 1 1 grade per fertilised oocyte).

Cryopreservation (cryopreserved embryos per fertilised oocyte).

Live birth implantation rate (live birth per embryo transferred).

Utilised embryos (number of cryopreserved plus transferred embryos per fertilised oocyte).

Top-quality utilised embryos (number of high-quality embryos transferred plus blastocyst cryopreserved of 3 1 1 grade per fertilised oocyte).

Statistical analysis

Sample size estimation

This is a three-arm study looking at pH over a range of 7.2–7.4. The hypothesis to be tested is that adjusting the pH value to the edges of this range might result in improvements to the live birth rate, although we remain in equipoise as to whether higher or lower values will be optimal. On the basis of internal data, live birth rates in the region of 25%–35% are typical, and our goal is to investigate whether this is associated with varying pH levels.

The study has been powered for a global test of the effect of pH, calculated using plausible birth rates in the three groups of 25%, 30% and 35%. A total of 646 participants per arm yield 98% power in this scenario, using a 5% significance level. This test makes no assumption about the ordering of the live birth rates in relation to the ordering of the pH values. The high-power level has been adopted to allow for some leeway in relation to the minimum effect size. For illustration, if the birth rates were slightly less distinct, with 26%, 30%, 33% (a spread of just seven percentage points) this sample size yields 85% power against a 5% significance level, and 65% at a 1% significance level. We have also been conservative in our inflation of numbers for dropout. We have allowed for 5% loss to follow-up, inflating our group size to 680. In reality, we will conduct the analysis on an intention to treat basis, including all randomised women. Women who do not complete treatment (eg, they do not undergo embryo transfer) will be counted as not having live birth, and so do not represent a reduction in sample size. The only exceptions to this will be participants who withdraw consent for their data to be used in the study. Our inflation for loss to follow-up reflects this possibility. We also note that adjustment for site and age in the analysis will increase power further.

Analytical methods

The study will be conducted according to the intention-to-treat approach, where each participant randomised will be included in the analysis, regardless of protocol deviation. The primary analysis of live birth will be conducted using logistic regression, with live birth events regressed on pH groups, adjusted for study site and participant age, which will be standardised before being entered as a covariate. pH will be entered as a categorical covariate, allowing a likelihood ratio test of the association between pH and live birth rate across the three groups to be performed. Secondary supportive analyses will be conducted to try to characterise the nature of any association. This will include a test of a linear trend in live birth rates across pH groups, which would imply an optimal pH level for the lowest or highest value, as well as pairwise comparisons between each group (again, these analyses will be adjusted for site and age). The pairwise comparisons will focus on size and precision of the ORs. Although it would be desirable to power the study for all pairwise comparisons as the primary outcome, this yields impracticable sample sizes (>4000 participants) against realistic effects. The study has therefore been designed to represent the most informative test of the hypothesis that pH level affects live birth, which is practicable.

For secondary outcomes, binary variables will be analysed in an analogous manner to the primary analysis. Count variables will be analysed using Poisson regression, with zero-inflated models wherever the outcome is structurally undefined for some participants. Again, these will be adjusted for site and age. In the analysis of the number of usable embryos, implanted embryos arising from day 3 transfer will be included as formed and good quality blastocysts, whereas those that do not implant in this portion will be considered blocked on day 3. Utilisable embryos will be calculated as the total number of transferred embryos and formed blastocysts. A 1% significance level will be used. Due to the short treatment duration, it is anticipated that loss to follow-up will be minimal (it is unusual for patients not to return to the clinic to have their embryos transferred, eg). However, if any loss does occur, these participants will be analysed as having a negative status for the primary outcome, unless consent to use data is withdrawn. The follow-up period is identified as 1 year from randomisation of the last participant provided that all pregnant women have given birth.

Ethics and dissemination

The Ethics Review Board of the Upper Egypt IVF Network relating to the participating sites approved this trial (Approval No. 009/2016). An independent safety and monitoring committee formed of five experts in reproductive endocrinology, reproductive biology, embryo culture, biostatistics and trial methodology will oversee the conduct of the trial. All participants will receive independent counselling from research instructors who are not involved in patient care or laboratory work. Participants who agree to participate will sign a written informed consent before enrolment. This study will be conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.21 The trial reporting will be according to the CONSORT statement.22 No plan exists to amend this protocol and any amendments will require the approval of the safety committee, and will undergo detailed reporting on the trial registry and in the final manuscript.

Discussion

Given the lack of evidence for a superior pH level for human embryo culture and whether the pH level could make a difference in live birth after IVF, a trial is warranted. This trial is expected to fill the gap in this area as at present embryologists must rely on the recommendations of culture media manufacturers rather than on a robust evidence base. This trial is powered to a high level (>90%, with a 1% significance level) against clinically important differences to minimise the risk for uninformative results. In the case of cleavage-stage transfer, the calculation of formed blastocysts will be based on the assumption that implanted embryos represent formed blastocysts, whereas any transferred embryos that fail to implant will be counted as blocked at the cleavage stage. Although this definition will be subject to some error, we believe it is a reasonable way to assess blastocyst formation without excluding a portion of the data. This point will be further discussed when this trial is reported. A large number of secondary outcomes will be measured and reported. This is partially driven by adherence to a recently developed core outcome set for infertility trials,20 as well as by the inclusion of some embryological variables that might shed light on the mechanism of any effects of pH levels. As is usual in clinical trials, type 1 error is controlled by the fact that the study inference will be based on the primary outcome variable, live birth. Accordingly, we will interpret the results of secondary endpoints cautiously in the final report as these endpoints are not subject to type 1 error control.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @jd_wilko

Contributors: MF: creator of the concept and design of the study and is the principal investigator of the study. MF: also a supervisor for the conduct of the study across the sites and will ensure that data is periodically sent for storage in an independent database. JW: statistician of the study who revised the study design and calculated the sample size and power of the study and he will be responsible for the data analysis and data transfer to the independent safety and monitoring committee. ME: primary investigator at Banon IVF Centre and a subinvestigator at Ibnsina Centre, participated in revising the trial protocol and will participate in trial reporting thereafter. RM: primary investigator at the Egyptian IVF-ET Centre, and revised the trial protocol and provided advice during the protocol design. AM: andrologist of the study who will ensure all male partners meet the inclusion criteria, and revised the protocol and provided comments. AF: primary investigator at Banon IVF Centre and participated revising the protocol and provided comments. MAR: participated in the trial design and is a primary investigator at Amshaj IVF Centre. HA: primary investigator at Ibnsina IVF Centre and participated in the trial design. All authors provided comments and agreed on the study design and protocol, and will participate in reporting this trial hereafter.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Smith ADAC, Tilling K, Nelson SM, et al. . Live-Birth rate associated with repeat in vitro fertilization treatment cycles. JAMA 2015;314:2654–62. 10.1001/jama.2015.17296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berntsen S, Söderström-Anttila V, Wennerholm U-B, et al. . The health of children conceived by ART: 'the chicken or the egg?'. Hum Reprod Update 2019;25:137–58. 10.1093/humupd/dmz001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pool TB, Schoolfield J, Han D. Human embryo culture media comparisons. Methods Mol Biol 2012;912:367–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Swain JE. Is there an optimal pH for culture media used in clinical IVF? Hum Reprod Update 2012;18:333–9. 10.1093/humupd/dmr053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tarahomi M, de Melker AA, van Wely M, et al. . pH stability of human preimplantation embryo culture media: effects of culture and batches. Reprod Biomed Online 2018;37:409–14. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shalgi R, Kraicer PF, Soferman N. Gases and electrolytes of human follicular fluid. Reproduction 1972;28:335–40. 10.1530/jrf.0.0280335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Phillips KP, et al. Intracellular pH regulation in human preimplantation embryos. Hum Reprod 2000;15:896–904. 10.1093/humrep/15.4.896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. FitzHarris G, Siyanov V, Baltz JM. Granulosa cells regulate oocyte intracellular pH against acidosis in preantral follicles by multiple mechanisms. Development 2007;134:4283–95. 10.1242/dev.005272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dale B, Menezo Y, Cohen J, et al. . Intracellular pH regulation in the human oocyte. Human Reproduction 1998;13:964–70. 10.1093/humrep/13.4.964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lane M, Baltz JM, Bavister BD. Na+/H+Antiporter activity in hamster embryos is activated during fertilization. Dev Biol 1999;208:244–52. 10.1006/dbio.1999.9198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Swain JE, Pool TB. New pH-buffering system for media utilized during gamete and embryo manipulations for assisted reproduction. Reprod Biomed Online 2009;18:799–810. 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60029-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hentemann M, Mousavi K, Bertheussen K. Differential pH in embryo culture. Fertil Steril 2011;95:1291–4. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carney EW, Bavister BD. Regulation of hamster embryo development in vitro by carbon Dioxide1. Biol Reprod 1987;36:1155–63. 10.1095/biolreprod36.5.1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Edwards LJ, Williams DA, Gardner DK. Intracellular pH of the mouse preimplantation embryo: amino acids act as buffers of intracellular pH. Human Reproduction 1998;13:3441–8. 10.1093/humrep/13.12.3441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Edwards LJ, Williams DA, Gardner DK. Intracellular pH of the preimplantation mouse embryo: effects of extracellular pH and weak acids. Mol Reprod Dev 1998;50:434–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization Who laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Palermo G, et al. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte. The Lancet 1992;340:17–18. 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92425-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mortimer D, Cohen J, Mortimer ST, et al. . Cairo consensus on the IVF laboratory environment and air quality: report of an expert meeting. Reprod Biomed Online 2018;36:658–74. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Medicine ASIR, Embryology ESIG Istanbul consensus workshop on embryo assessment: proceedings of an expert meeting. Reprod Biomed Online 2011;22:632–46. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duffy JMN, Bhattacharya S, Curtis C, et al. . A protocol developing, disseminating and implementing a core outcome set for infertility. Hum Reprod Open 2018;2018:hoy007 10.1093/hropen/hoy007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Williams J. The Declaration of Helsinki and public health. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:650–1. 10.2471/BLT.08.050955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. . Consort 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c332 10.1136/bmj.c332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.