Abstract

Objective

To explore student physician associates’ (PAs) experiences of clinical training to ascertain the process of their occupational identity formation.

Setting

The role of the PA is relatively new within the UK. There has been a rapid expansion in training places driven by National Health Service (NHS) workforce shortages, with the Department of Health recently announcing plans for the General Medical Council to statutorily regulate PAs. Given such recent changes and the relative newness of their role, PAs are currently establishing their occupational identity. Within adjacent fields, robust identity development improves well-being and career success. Thus, there are implications for recruitment, retention and workplace performance. This qualitative study analyses the views of student PAs to ascertain the process of PA occupational identity formation through the use of one-to-one semistructured interviews. A constructivist grounded theory approach to data analysis was taken. Research was informed by communities of practice and socialisation theory.

Participants

A theoretical sample of 19 PA students from two UK medical schools offering postgraduate PA studies courses.

Results

A conceptual model detailing student PA identity formation is proposed. Factors facilitating identity formation include clinical exposure and continuity. Barriers to identity formation include ignorance and negativity regarding the PA role. Difficulties navigating identity formation and lacking support resulted in identity dissonance.

Conclusions

Although similarities exist between PA and medical student identity formation, unique challenges exist for student PAs. These include navigating a new role and poor access to PA role models. Given this, PA students are turning to medicine for their identity. Educators must provide support for student PA identity development in line with this work’s recommendations. Such support is likely to improve the job satisfaction and retention of PAs within the UK NHS.

Keywords: health policy, organisation of health services, medical education & training, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first research article to offer an in-depth exploration of professional identity formation within UK physician associate (PA) students.

A qualitative, constructivist approach has generated detailed data that has allowed us to craft a conceptual model describing the key influencing factors on student PA identity formation.

The PA role is still being established in the UK—this context could limit the transferability of our findings but this work remains relevant as the role is establishes in other countries internationally and in acting as a benchmark for future UK student PA identity research.

The number of participants from each institution was not equal: n=14 from institution 1, n=5 from institution 2—given this, some student experiences may be institutionally specific and future work should focus on wider national and international recruitment of PA students to refine the conceptual model proposed by this work.

There is a predominance of female participants (M:F 5:14), which limit result transferability to male students, although this balance is representative of the female predominance within PA studies.

Introduction

The role and purpose of the physician associate

The role of the physician associate (PA), although well established in some countries (where it is referred to as ‘physician assistant’), is still in its infancy within the UK. The UK PA role was modelled on the physician assistant role that has been established for over 50 years within the USA.1 UK PAs are ‘new healthcare professional(s) who, while not doctor(s), work to the medical model, with the attitudes, skills and knowledge base to deliver… care and treatment within the general medical/general practice team under defined levels of supervision’.2 Supervision should be directly provided by a licensed physician.3 Working PAs support doctors in the diagnosis and management of patients through history taking, performing clinical examinations, formulating differential diagnoses, ordering and analysing test results, and developing and implementing management plans.3 Training as a PA is a graduate endeavour,4 with student PAs generally holding an undergraduate biomedical science degree. Student PAs are trained in a ‘medical model’, ‘focus(ing) principally on general adult medicine in hospital and general practice, rather than specialty care’.5 6 PA courses last a minimum of 3600 hours over 2 years, with hours being equally split between medical theory and clinical practice.3

The expansion of the UK PA workforce has been driven by an urgent need to address medical workforce shortages, particularly of doctors, within the National Health Service (NHS). The research arm of the NHS, the National Institute of Health Research has funded two seminal studies on the contribution of PAs in primary care7 and acute secondary care.8 The studies showed PAs were acceptable to patients and likely to be cost-effective in these settings,7 8 increasing the capacity and continuity of patient care.9 In 2016, there were 260 PAs and 550 PA students across England and Scotland6 with 1000 more PAs promised by the Secretary of State for Health within general practice by 2020/2021.10 Although PA training places are increasing, this recruitment target for general practice looks to be overly optimistic—in March 2019, there were 194 PAs working in general practice (167 full-time equivalent (FTE) PAs) and, although an additional 97 FTE PAs were employed between 2018 and 2019, this figure and pattern of growth will likely still fall short of governmental targets.11 Although PA training places are increasing, 72% of qualified PAs still work within secondary care.12

Despite such rapid expansion in deployment, PAs are struggling to establish their role as a core constituent of the multidisciplinary team. Within the UK, PAs are classed as a profession (although a new one), as there are no legal requirements as to the definition of a profession in the UK, and new healthcare professions establish themselves through practice. The UK legal system does, however, draw distinctions between unregulated and regulated professions, with regulated professions requiring individuals to register with a designated authority, so the individual can be evaluated as to whether they are competent and qualified enough to practice safely.13

PAs are not yet statutorily regulated within the UK, but this seems likely to change soon,14 with recent news breaking that the UK General Medical Council (GMC), the regulator of medical doctors, has been asked by the Department of Health to regulate PAs.15 Statutory regulation through the GMC would mean UK-based PAs could expand their occupational capabilities. Currently, PAs cannot obtain qualifications that would enable them to prescribe medication or ionising radiation, but statutory regulation is likely to pave the way to such rights.4

Even with possible regulatory changes, PAs and the systems in which they work, are still trying to establish PAs as core team members. This involves PAs navigating the development of their new profession’s occupational identity. Health Education England (HEE) has recognised this as a potentially difficult area to navigate and is currently working to ‘develop a career framework and professional identity’ for PAs.16

Further investigation regarding PA professional identity is crucial. Medical professional identity formation is described as ‘the foundational process one experiences during the transformation from lay person to physician’ and concerns education regarding the ‘core values’ healthcare professionals.17 A strong sense of identity enables healthcare professionals to ‘practice with confidence…convincing others of their practical abilities’.18 Indeed, acquiring a strong professional identity has even been found to protect against burnout19 and ultimately enhance career success.20

However, almost all data on how clinicians form their professional identity have been focused within the domain of medical undergraduate students.17 21–27 Traditionally, the field of medicine ‘has been referred to as the very embodiment of the concept of professional identity’28 with doctors ‘being treated as the archetypal healthcare profession.’29 Doctors as a universal standard for professional identity development within healthcare risks a ‘one size fits all’ model of identity development, particularly when you consider that PA students are different from undergraduate medical students in regard to their training and emerging role. Yet, while using doctor-based models risks harm in encouraging student PA identity development, there are no published papers to date examining professional identity formation within UK PA students. Even internationally, work investigating student PA identity is sparse. Early work from establishing the physician assistant role in the USA details the difficulties and conflict physician assistants sometimes faced in positioning themselves within the medical hierarchy, hinting that such positioning influences identity formation, with conflict acting as a negative influence.30 Despite this, to the authors’ best knowledge, detailed work is yet to be published studying identity formation within the development of the PA role on an international or national stage.

As such, new, exploratory models for professional identity formation within student PAs warrant further investigation. The central research question of this work regards identifying the process of occupational identity formation within PA students, focusing on factors that they identify as facilitating or obstructing identity development. It is hoped research within this area will generate both recommendations for educators regarding supporting student PA identity development, and recommendations for HEE regarding developing a career framework and national identity template for PAs.

Materials and methods

Context

The context of this study was two postgraduate PA studies courses—one at the Hull York Medical School (HYMS) and one at the University of Sheffield. PA studies courses at both institutions are operated as part of the medical school, although remain distinct from the medical undergraduate degrees. For admission onto both courses, applicants must hold a degree in a life or health science (typically in a biomedical science) and preferably have some form of prior healthcare experience. Both institutions are based in medium-sized urban cities, but clinical placements include postings in more rural surrounding areas. HYMS holds training places for 30 student PAs each intake, with Sheffield holding 20 training places. At the time of this study (data were collected during 2018–2019), the course at HYMS was in its third year of operation, with Sheffield in its fourth year. Given this, both areas are relatively ‘PA naïve’, in that associated hospitals and general practice surgeries are only just beginning to employ PAs in practice.

Study design and conceptual framework

Working within a constructivist paradigm, we acknowledge that we, as researchers, play an active role in data analysis and theory generation. As such, it is important to detail our backgrounds to allow for interpretation of our study conclusions. All researchers are medical education researchers. One researcher is a professor of medical education (GMF) and three researchers are qualified clinicians (MELB, PAT and WL). One researcher is a clinical education tutor on the HYMS PA studies course (WL). Operating within a constructivist paradigm, we recognise that there is no one single reality or objective truth—instead, multiple realities exist that are created by individuals within social settings.31

This work undertook inductive qualitative study. The methodology selected for use was constructivist grounded theory.32 33 Background literature was read throughout this work to generate a conceptual framework in which generated categories were able to be situated. This conceptual framework is detailed below.

All researchers reflected on their own biases and preconceptions and engaged in a group discussion concerning reflexivity to consider their own perspectives in more detail. Within this discussion, WL’s involvement in the HYMS PA studies course was discussed. It was decided WL should not interview any student he had involvement in teaching, to maintain as a neutral interviewer–interviewee relationship as possible and that all transcripts should be independently dual coded.

Conceptual framework

Pre-existing professional identity theory should be cautiously applied to PA students, given no work regarding identity formation within PA students has been done. Although medical undergraduates operate within a largely similar environment to PA students, there are significant differences between medical students and PA students including differences in clinical experience, age, maturity and career choice. It remains unclear whether the bulk of pre-existing identity literature adequately reflects the development process and experience of student PAs. Difference also exists in that student PAs may enrol in their studies with an already well-developed previous clinical identity (eg, as a nurse or paramedic) due to entry requirements of the course often stipulating the need for clinical experience. Unlike medical students, student PAs may undergo a process of identity transformation that involves moving from one well established identity to another, as opposed to forming a professional identity on a largely blank professional canvas. Considering all this, previous literature was used as a broad theoretical underpinning to explore the concept of identity formation within student PAs more specifically. Identity literature regarding the transformation of professional identity from one profession to another was also sought.

Unfortunately, there is no consensus among educational researchers as to the most applicable theoretical approach to studying professional identity development.34 However, several theories are becoming more commonly used to detail the nuances of identity development.34 Lave and Wenger’s theory of communities of practice and Cruess et al’s process model of socialisation are drawn on by this work to act as sensitising concepts to data analysis.

Identity involves community membership—individuals define themselves through involvement in a ‘community of practice’.35 A community of practice is defined as ‘groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly’,36 with social interactions resulting in an individual moving from legitimate peripheral participation to full participation.37 Within a community of practice, individuals undergo a process known as socialisation, where students ‘learn to function within a… group by internalising its values and norms’.29 Navigating socialisation can be difficult but is necessary to acquire new professional ‘subidentities’, altering one’s perception of self and leading to successful function within a new occupational role.34 36 Regarding identity transformation from one occupation to another, work within other occupations has demonstrated that, in order to acquire a robust professional identity within a new career field, various previous identities require reconciliation and integration into one’s new identity.38 Such reconciliation occurs within communities of practice—as students move from novice to old-timer, their new ‘subidentities’ change their self-perception34 36 and, with this sometimes difficult change, comes re-evaluation of previously held identities.38

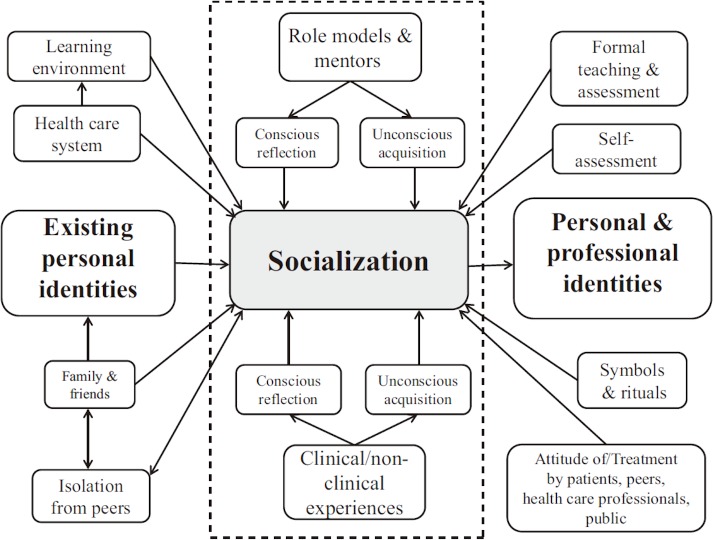

Within socialisation, many factors are at work that influence physician identity, for example, role modelling. Cruess et al offer a schematic representation of socialisation and it’s influencing factors in figure 1.29 These factors acted as sensitising concepts for our data analysis.

Figure 1.

Cruess et al’s diagrammatic representation of factors impacting on a medical student’s process of socialisation in identity formation.

This theoretical framework, detailing how identity is socially situated in its formation and drawing on communities of practice and socialisation theory has been used to act as a sensitising concept for data analysis and interpretation throughout this work.

Data collection

Theoretical sampling was used, aiming to recruit PA students who had clinical placement experience. Given this, all PA students within year 1 or 2 of study at HYMS and year 2 of study at Sheffield were invited to interview through the use of email, posters and word of mouth. Participation was voluntary, and consenting students contacted the research team by email to organise an appropriate interview time.

Two authors (MELB and WL) conducted semistructured interviews, both face-to-face and at a distance via telephone call, Skype or FaceTime. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Demographic information from the participants of this work concerning gender, age, race, ethnicity and sexual orientation were collected—recent work has demonstrated that models of professional identity formation often do not pay heed to participants’ sociocultural data, generating uncertainty as to whether much work into identity formation is applicable to those who do not identify as heterosexual white males.39

Data analysis

Semistructured interviews were conducted in line with an iterative approach, with initial question stems (see online supplementary table 1) evolving as data collection and analysis occurred concurrently. All members of the research team engaged in discussion throughout the research process to determine when both theoretical sufficiency, the point at which no new thematic categories were required to manage new collected data,40 and ‘information power’41 42 had been reached. These discussions concluded that all interviews represented an adequate sample size that both answered the research questions of this study and allowed for transferability of the results to other contexts.

bmjopen-2019-033450supp001.pdf (33.9KB, pdf)

Grounded theory coding in iterative cycles with constant comparison was conducted by all members of the research team, ensuring each transcript was coded by at least two researchers to deepen analysis. Open, focused and theoretical coding were conducted, with memo writing used throughout. All members of the research team engaged in a discussion concerning content groupings following open coding to ensure internal validity. Final coding was used to generate a conceptual model encapsulating student PA occupational identity formation.

Study results were shared with all core PA tutors within HYMS (five tutors) for feedback, as a way of triangulating collected data. No feedback was provided that changed the data analysis.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient involvement, as it does not directly involve patients as research subjects. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Results

A total of 19 PA students completed our study, 14 from the HYMS and 5 from the University of Sheffield. Demographic information can be viewed in table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographic information

| Gender | Age | Sexual orientation | Ethnicity | Prior healthcare occupational experience? |

| M:F 5:14 | Range: 22–32 Mean age 25 |

Heterosexual or straight: 18 Gay: 1 |

White British:14 Black British: 1 Black African: 1 Mixed ethnicity: 3 |

Y:N 9:8 Most common job role: healthcare assistant |

Themes

Preliminary analysis identified 98 descriptive open codes from interview transcripts. These codes were organised into 3 major themes, 6 subthemes and the initial descriptive codes collapsed into 31 open codes. These are detailed in table 2.

Table 2.

Major themes, subthemes and open codes

| Major themes: | Recognition | Formation | Dissonance |

| Subtheme 1: | Awareness of the PA role | Helpful in forming identity | Identity crises |

| Open codes: | Role ignorance | Peer support | Emotional situations |

| Documentary delays | PA faculty | Failing | |

| Proving utility to gain trust | Clinical exposure | Workload | |

| Open minded staff | Responsibility/autonomy | Comparison with medics | |

| Incorrect introductions | Continuity | Work environment | |

| Treated as medical students | Resilience | ||

| Making a difference | |||

| Subtheme 2: | Resistance to the PA role | Role modelling | PAs on the political agenda |

| Open codes: | Negative staff perceptions | Being an ambassador | Competition from medics |

| Distress at role aversion | Distant role models | Place for role | |

| Negativity affects learning | Doctors as role models | A path to medicine | |

| Lack of role models | Governmental support |

PA, physician associate.

Global theme 1: recognition

Awareness of the PA role

Recognition of the PA role was identified as an important element of all student PA participants’ professional identities. Recognition involved others being aware of the existence and nature of the PA role, yet this was often found to be lacking.

A lot of people have never heard of us…some people don't have a clue what we're able to do. Participant 2

I'm yet to come across anyone that actually knows what a PA is so far… Participant 5

In many cases, this resulted in incorrect introductions where PA students would be introduced as an alternative role by staff.

I've definitely had experiences where it's like, ‘oh we'll just call you a medical student’ or ‘we'll just call you a trainee doctor’ rather than actually going through what I am. Participant 1

I've been called medical student, doctor, physician's assistant, nurse… Participant 11

Students found such incorrect introductions disconcerting and often found the onus on them to explain the role.

I kind of feel a little bit like a conman…I feel a bit like I'm deceiving people and being a bit of a fraud in that sense. Participant 1

Sometimes I will try and help them understand… Participant 3

In the face of poor awareness of the PA role, students valued working with both staff with prior exposure to PAs and those with open minds. When such positivity was lacking, students felt pressure to prove their utility to clinical teams to gain trust.

I was working with an F1 who trained down in Kent and she's had previous exposure to PAs, and she was really positive and really selling the role basically to all the people on the ward. Participant 13

I always feel like I have to sort of give something back to get sort of learning out of it. Participant 12

Resistance to the PA role

PA students perceived overwhelmingly negative attitudes towards their role.

I have noticed there's been times where someone's assumed I'm a medical student or a junior doctor and have been really friendly and helpful and then it's almost as if they find out what a physician associate is and it switches and they don't really want to talk to me again after that. Participant 2

…they're like 'oh if you're not a medical student it's fine, like, we don't need you'. Participant 1

Negativity often took the form of pressure on students from doctors to consider medicine as a career instead of becoming a PA.

…surely the reason you've been chosen as a supervisor is because you're meant to be like promoting the role, but he wasn't at all. He was trying to encourage myself and my partner at that time, who later left, to apply to do medicine…that was quite off-putting, because I was thinking 'oh, what if I didn't choose the right role'… Participant 16

Students found negativity difficult to challenge, distressing and commented on the negative impact it had on their learning.

…I wanted to be professional on placement and continue my learning, so I generally didn't say anything back… Participant 14

I remember in first year myself and some of the other students were told by a consultant, basically not to give up your day job because the physician associate role's never going to go anywhere…that was like quite upsetting to hear that. Participant 2

… it does shut you down and you don't want to be open and learn what you can learn… Participant 7

Despite the prevalence of perceived negative attitudes towards student PAs, there has been a recent improvement in attitudes students perceive from others, secondary to role familiarity. Yet students often drive this attitude change through consistent effort, as opposed to institutions leading the way.

I think it's kind of changed a bit from the beginning of the course to the end…they got a bit used to who we are. Participant 11

I just felt like I had to make a good impression everywhere I went because there were other people that were going to follow after me and making that good impression would mean the next lot would have it easier. Participant 7

Global theme 2: formation

Helpful in forming identity

Students identified several influences as being helpful in the formation of their professional identity. Clinical exposure, in particular ‘deep end’ service learning and students witnessing their interventions making a difference accelerates identity formation.

…placement is the place where I feel like, there are instances where I go 'yeah, yeah I'm a PA'. Participant 16

Certain people will throw you in at the deep end and that was the case on X care at X hospital, the consultant was very much using us as extra staff but it worked really well…you had to quickly learn…you were very much part of a team and I could see how the PA role fit in. Participant 19

…when you actually do something that makes a change to a patient and you can see that change that's when you actually feel like, 'OK I'm the real deal now'. Participant 11

Students felt more like PAs when they were given some degree of responsibility or autonomy, preferring such independence to be within a supported environment.

I was having the responsibility of seeing my own patients …and, it made me think, I'm going to be doing this soon in real life and I'm sort of ready to move onto that step now. Participant 14

I think having that independence is definitely good while we're still learning. The pressure isn't on you. Participant 10

Students often identified their elective placements as instrumental in shaping them as PAs. Continuity was identified as a key reason for this effect, assisting in overcoming role ignorance.

…during my elective again, I think that was just the biggest because it was five weeks in just one area…I was pretty much working at that point and I was just kind of obviously running it past people, and I was seeing patients on my own and stuff like that. I think that's when I thought, this is kind of me doing the job. I've never had that before. Participant 4

People got a bit more used to us and they started to realize what we could do. Participant 11

Resilience was identified by many students as a key part of their professional identity, often borne of necessity due to workplace negativity.

I think my professional identity would have to be quite resilient because of everyone's perception of the role. Participant 14

Role modelling

Role modelling was identified as an important factor in shaping student PA professional identity, but there were difficulties with this, given the relative scarcity of working PAs. Students found it difficult to access role models and lamented the fact they had not had the chance to interact with a qualified PA, expressing preference for role models to be PAs themselves, as opposed to doctors.

…it would be nice to see a physician associate and what they can do. Participant 3

…it was a bit scary not having someone to be like 'well how did you handle this'. Participant 10

One way some students attempted to circumvent a lack of role models was through accessing distant PA role models, often done via social media.

…you can just use Twitter or something like that to find them. Participant 2

Given such deficiency, students felt pressure to become ambassadors for the PA role. Some found this exciting, but others felt the responsibility weighed heavily on them.

…it sort of rang in our heads that we were pioneers, that we had to be out there, no one knew about us. It was our job to make them accept us in a certain way. So I felt like a pioneer and definitely enjoyed it. Participant 7

I still feel like I'm being watched. Participant 16

In the face of this deficiency, some students gravitated towards using doctors as role models, and had begun to identify more with the medical profession than with PAs.

…we can view doctors as role models. Participant 8

I plan on going to med school, yeah… what PAs do is similar to foundation doctors but then like the progression is not there…. as I’ve gone on and seen doctors working and, um, seen that responsibility and autonomy, it’s something I want too. Participant 18

Global theme 3: dissonance

Identity crises

Students universally believed they had experienced an ‘identity crisis’ at some point during training. The triggers of these crises took many forms such as failure, the burden of course workload and students expressing doubts following comparison with medics.

I ended up failing that OSCE … that made me question you know, am I actually good at this, am I competent to do this. Participant 5

… you sometimes feel like you're held to the same standard as a medical student, if not more, in terms of workload and then someone can just undermine you on the spot and be like 'you're not a medical student, you can't be my chaperone'. Participant 1

…when you compare the two professions then you think, like one seems to have a much easier time of it… being a doctor is a really respected profession, you say you're a doctor and people don't argue but you say you’re a physician associate and they're like 'ok, what's that then?', they don't necessarily take what you have to say seriously. Participant 15

Students expressed identity difficulties early in their training, often within the first year.

I think in first year; everything was a bit overwhelming… I was second guessing or doubting myself. So that was my problem at first, I had so much doubt in everything I was doing… having sleepless nights whether I’ve actually done the right thing… signing up. Participant 9

Several students dealt with such crises in a way (eg, through peer or family support) that negated any harmful effects, but, concerningly, over half of the participants displayed signs of identity dissonance, where assuming the PA role was often likened to wearing a mask. Students portrayed these feelings as sustained and unresolved—resolution of identity difficulty was not described by any participants displaying signs of identity dissonance.

…it’s kind of like having a mask on. Participant 6

…sometimes I feel like I have to put a good face on it all when I’m out on the wards, like… almost like I have to step into that PA role, it’s not natural… when I put the lanyard and badge and stuff on it’s like putting on a mask. Participant 8

PAs on the political agenda

Students voiced concern regarding a lack of progress at a governmental level, with such uncertainty identified as negatively impacting on identity.

I think one of the things that's quite demoralising is the whole thing about regulation and how slow it's been taking. Sometimes you kind of question, 'God, have I made the right decision?'. Participant 3

I just don't know what's going to happen in five years’ time. There is no like model for the next five years…no one knows where we'll be working. Participant 1

Some students felt so frustrated by this lacking progress that their professional identity already showed signs of transformation into the professional identity of a medical student, which is perceived as more accessible and progressive than that of a PA’s.

I think if an opportunity came up, maybe, not necessarily now but in a couple of years and they were like, you can do some sort of conversion course to do medicine, I probably would take it…I just do feel like we can't really progress as much as they marketed it because we can't prescribe and we're not regulated yet. Participant 11

I feel like we have so many obstacles in the way, whereas if you were to read medicine they wouldn't be there Participant 17

Others had very clearly already undergone such an identity transformation and admitted to using the PA course as a path to medicine. One student even referenced medicine as an ‘upgrade’ to PA studies.

I'm going to go into medical school after this degree…I do enjoy being a PA…but I do want to be able to upgrade… as a doctor you get a chance to progress more. Participant 6

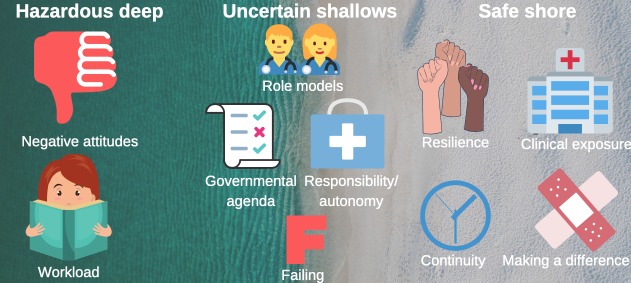

The findings of this work have been used to produce a conceptual model (figure 2) offering initial insight into student PA professional identity formation.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model detailing the facilitating factors and barriers to student PA identity formation. There are three sections to this conceptual model. The ‘safe shore’ is solid ground on which student PAs can easily find their footing and represents the factors which assist student identity formation. The ‘hazardous deep’ can easily drown a student, and represents barriers to student identity formation that can overwhelm a training PA. The ‘uncertain shallows’ is a hinterland between the safety of the shore and the dangers of the deep and represents factors that, depending on context and agency, can either help or harm student PA occupational identity formation. PA, physician associate.

Discussion

Key messages and suggested actions for educators and policy-makers

Message 1: role recognition is key to community of practice participation and subsequent identity formation

Students acknowledge recognition of their role as a student PA as important in the formation of their professional identities, yet this was lacking. As evident within this work’s theoretical framework, inclusion and active work within a community of practice is essential for robust identity formation.35–37 Takahashi and Bertino take this further and highlight the importance of role recognition within a community of practice, stressing that those with strong professional identities hold a ‘well-defined status’.40 It is clear student PAs struggle acquiring such a status, with supervisors often mislabelling their role and introducing student PAs to patients as ‘medical students’. Failure to acquire a well-defined role or status within community of practice theory results in individuals remaining on the periphery of their community, unable to gain mastery of their profession as their role remains unclear.34 36 41As long as PAs remain peripheral to the medical community of practice due to lack of role definition, they will struggle to acquire strong professional identities or gain true mastery of their profession. Within wider occupational literature this proves damaging, with confusion over role definition leading to worsening morale and self-esteem within employees.42

Educational institutions must strive to better integrate student PAs into medical communities of practice by educating both supervisors of students and the rest of the multidisciplinary team as to the student’s current and future role, competencies and learning outcomes. A brief introduction detailing these elements to a ward or general practice’s multidisciplinary team, delivered at handover or a practice meeting by a student’s clinical supervisor, could go a long way to educating clinical staff regarding the PA role. Written information for staff would also prove a useful reference—informational posters or pamphlets in staff areas would provide easily accessible information regarding the PA role.

Nationally, a more vigorous and targeted educational campaign by HEE or the NHS is also necessary to improve staff awareness of all roles of the multidisciplinary team. This campaign could take many forms—one approach could be the development of a national e-learning package regarding the PA role and dissemination of this as required learning to all healthcare professionals.

Message 2: negativity persists and damages student identity formation

There is some evidence PAs encounter mostly positive attitudes while at work. In 2012, a survey of UK doctors who worked with PAs found that only 3.3% believed having a PA on their team did not work.43 However, this survey was conducted with doctors working directly with PAs on a regular basis and so must be interpreted within this context, understanding that exposure and awareness could impact perceptions. As PAs are still a relative minority within the workplace nationally, demonstrating largely positive attitudes through such work is likely not truly representative of wider occupational attitudes towards PAs.

Overall, there is a greater volume of evidence suggesting PAs encounter negative attitudes in the workplace.44 45 In this context, negative attitudes are defined as the perception of another’s viewpoint from hostile comments or actions made within the workplace.44 Before the introduction of PAs in the UK, the most recently established role was that of the advanced nurse practitioner (ANP). Work assessing barriers to PA introduction found ANPs were concerned PAs would encounter stereotyped and prejudiced views, as they had when they were forging their role with staff not used to working with ANPs.46 This work is supported by Drennan et al who uncovered largely negative opinions concerning the PAs from both senior and junior doctors and nurses with a variety of exposure to working PAs, ranging from no to regular contact.44 Such hostility is likely a form of professional protectionism towards a ‘new and potentially competing occupational group’.46 However, Drennan et al’s work must be interpreted cautiously—it is not clear within their work which participant quotes come from those with exposure to the role and which do not and, as such, the nature of these negative attitudes is difficult to discern. Despite this, our work adds contemporary weight to the claim negative attitudes regarding PAs exist within the workplace from a variety of healthcare professionals, although negativity from senior medical staff was most frequently described. Students most frequently portray such attitudes as coming from those with little to no previous experience of working directly with PAs. A novel finding of this work is how damaging such negativity is to student PA professional identity formation, promoting identity dissonance.

Educational, medical and national institutions must adopt a firm stance regarding negativity towards the PA role and openly confront role negativity. This would send a clear message to students and working PAs regarding the value of their role and the support available to them. Ideally, this should be explicitly confronted within the first few weeks of the PA course, and certainly before clinical exposure. Advice should be offered regarding responding to negativity in the moment, signposting to appropriate student support and increasing awareness of any institutional complaint procedures.

Message 3: responsibility and clinical continuity facilitate identity formation

Much work has been done within medical undergraduate students investigating factors that encourage robust professional identity formation. Factors often cited as helpful include: the availability of mentors and role models26 27; clinical experiences and formal teaching and assessment.47 The present study echoes these findings. Further to this, student PAs identified responsibility and autonomy as pivotal in crossing the threshold into becoming a PA.

Within medicine, a student also sensing their responsibility and continuity of clinical exposure are both key to students identifying as belonging to a particular community.48 This resonates with our findings. Continuity of clinical environment may be difficult to obtain, given student PAs require generalist training within a relatively short time frame. Solutions to this problem are not likely to be easy or without cost but could greatly impact on student learning and identity formation. It is important to note that there is a move within some institutions to place students at one trust, where possible, for the duration of their training to facilitate continuity (this was not the case at the institutions studied in this research). This may be one way of offering more continuity of clinical experience and fostering identity development. Addressing continuity is key as continuity of placement facilitates staff trust in students and increases the likelihood of staff providing students with a greater degree of responsibility.

Message 4: PA role models are lacking, causing student PAs to model themselves on medical doctors

Role modelling was mentioned frequently within interviews with student PAs. Although the bulk of previous literature portrays role modelling as a factor helpful in professional identity formation,28 29 35 student PAs were not as convinced. Students acknowledged the lack of PA role models and commented this deficiency made acquiring a professional identity more difficult. Furthermore, the purely physician role models currently available to student PAs have caused some student PAs to begin to think, act and feel like a doctor, not a PA. This may explain why so many students in our work were considering training as a doctor after their PA course ended.

Institutions must actively recruit working PAs to teach on their PA studies courses, even if said working PAs are perceived as still being relatively junior. In time, as the quantity of working PAs increases, PA studies courses should be mostly led and taught by PAs. Alternatively, bringing working PAs to institutions for regular question and answer/information sessions or utilising social media to signpost and encourage online access of PA role models may prove helpful. Publication of national accreditation standards for PA studies courses, stipulating the need for adequate PA role model exposure could also help. Such accreditation standards have yet to be formally published, but could provide clear guidance to institutions on best utilising PA role models.

Within the US, debate exists as to whether to integrate physician assistant studies courses into medical school curricula. Overwhelmingly, PA programmes remain separate entities, with only two programmes (Boston University and Iowa University) achieving majority integration.49 50 Although the impact of medical school integration on student PA professional identity development has not been studied within this work, it could be argued demonstrating that student PAs relying on doctors as role models can alter the identity they form, makes a case for maintaining the separation of medical and PA programmes. Yet, such an assumption would be flawed, failing to pay heed to the significant body of literature regarding the benefits of interprofessional education. Indeed, interprofessional education can strengthen student identity formation—witnessing, and even performing, the role of an adjacent health professional has been found to reinforce student knowledge of and comfort within their own role.51–53 Student PAs within this work rarely saw any other working PAs. In the context of appropriate exposure to PA role models, alongside physician role models, cautious and careful integration could be of benefit to student PA identity formation.

Message 5: identity dissonance is prevalent and exacerbated by career uncertainty

Despite emerging awareness of factors influencing professional identity development, university students often struggle to develop robust professional identities, suffering emotional distress at the hands of a concept known as negative ‘identity dissonance’.54 When personal and professional identities fail to integrate as conflict exists between the two, students feel as though they are ‘losing themselves’, often leading to questioning regarding a student’s ‘values, ambitions, abilities and… self worth’.24 55

Within medical students, identity dissonance leads to higher rates of drop out and reduced career success.24 Student PAs display signs of such dissonance—all participants admitted to experiencing an ‘identity crisis’, often at an early stage of their training. Students manifest identity dissonance by distancing themselves from the PA role to maintain their sense of self, referring to the role as a ‘mask’, or by failing to acquire a professional identity as a PA, instead being content to be mislabelled as a medical student. Referencing PA identity as a ’mask’ could also be a way of students expressing feelings of ‘imposter syndrome’. Within ‘imposter syndrome’, individuals feel unworthy of the praise they receive ‘because they do not believe they have earned such recognition… causing… anxiety and stress’.56

It is possible, however, the difficulties student PAs describe in regard to their ‘identity crises’ are part of normal student identity development and not more sustained identity dissonance. Wenger describes how the process of ‘identity reconciliation’, where individuals make sense of their multiple subidentities and work to integrate these.35 41 57 Identity reconciliation can be difficult, particularly when entering a new community of practice,35 as the student PAs within this work recently had. However, some accounts given by students throughout this work seem to go beyond anticipated initial stress when faced with developing a new identity—a large proportion of relatively senior students interviewed still demonstrated identity difficulties, all students identified with the term ‘crisis’ to describe their identity struggles and many students admitted to struggling with a assimilating PA professional identity without any real resolution to these issues. It is likely a combination of identity reconciliation and identity dissonance are evident within our results—initial unsuccessful identity reconciliation can lead to identity dissonance and we believe this is evident here—over half of the participants admitting to struggling did not demonstrate successful reconciliation. As such, and alongside the time scale and severity of identity struggles within our work, we conclude identity dissonance to be present within our study participants.

This study is the first documented evidence of identity dissonance within PA students. Furthermore, a novel finding of this work is the damaging effect identity dissonance has on student learning—the ‘mask’ of imposter syndrome is a barrier to full student engagement and immersion within situated learning environments.

Identity dissonance and imposter syndrome are worsened by the career and political uncertainty surrounding the PA role. Mentioned frequently were concerns over the lack of standardised professional regulation, and the negative impact this had on student identity. Christmas postulates professional regulation offers a sense of identity through alignment with a wider community of professionals.58 Statutory regulation is on the horizon and this will likely positively influence PA occupational identity. Still, educational institutions would do well to honestly address student concern and fears regarding career progression and development. Nationally, clarity regarding PA career paths and progression is desperately needed from HEE to improve PA career satisfaction and future role retention.

Limitations

It is important to consider the limitations of this work. Context must be carefully considered throughout—the two institutions studied operate using different curricula and provide varying degrees of clinical exposure. Given that clinical experience within a community of practice is considered key to medical identity formation,29 this variable exposure is likely to have had an effect on students that we are unable to fully dissect without further study.

Another contextual limitation concerns the localities studied. At the time of this study, HYMS was in its third year of operating a PA studies course, with Sheffield in its fourth year. Given this novelty, the amount of PA graduates practising within the study region is likely to be limited, meaning this study’s results must be interpreted within the context of a PA-naïve area. It could prove difficult to fully extrapolate these findings to an area in which PA practice is more well established, and further work should focus on student PA identity formation within a wider variety of national and international localities. Despite this, this work still holds relevance, both for many areas within the UK, and internationally, particularly in areas still establishing the PA role. We do feel our findings and practice recommendations are also transferable in a broader sense and could apply to any new establishing role, particularly within healthcare.

The final considered limitation of this work concerns the demographics of the student population studied. There is a higher proportion of female participants which could act as a confounding factor—some of our findings could be borne of gender, not role, bias. Despite this, the gender balance of this work is representative of the female predominance present within PA studies,59 creating transferable results. It would be almost impossible and, indeed, fairly artificial to dissect out gender and role bias within this context. Instead, an intersectional approach is more appropriate, considering the possibility of gender bias acting alongside the profession bias this work has demonstrated.

Directions for future research

Novel findings warranting further research from this work include: the function of role modelling within PA students; identity dissonance within student PAs including investigation of the relationship between identity reconciliation and identity dissonance; and the finding that many PA students identify more with doctors, giving rise to a desire to subsequently train as a physician. As the number of PAs in the UK NHS grows, there will be further opportunities to evaluate the influence of training and workplace experiences on occupational identity, and how these impact job satisfaction, recruitment and retention. Ongoing evaluation of PA experiences regarding their identity development will add further depth to the conceptual model presented by this work and ensure support for PA identity development tackles current issues and enhances supportive factors.

Conclusions

This is the first in-depth qualitative study to focus on UK student PA professional identity formation. While the perception of PAs within the workplace is improving, secondary to role familiarity, students continue to experience negativity directed at their position as training PAs, proving harmful to identity formation. Student PAs identified several factors as instrumental in acquiring a strong professional identity, including clinical exposure including adequate continuity. Despite this, a lack of focus on PA identity formation has allowed harmful influences to propagate without intervention, such as ignorance and negativity from staff regarding the role. Early intervention is key—most students suffer ‘identity crises’ early within training that can progress to identity dissonance if no support is offered. Educators must act to continue to support the ‘safe shore’ identity facilitators and intervene in the ways detailed above to make the ‘uncertain shallows’ and ‘hazardous deep’ of identity formation safer for student PAs to navigate.

PAs are a key component of HEEs plans for the UK health workforce strategy. However, unless this emerging professional group form a healthy and coherent identity, long-term, recruitment, retention and workplace effectiveness are likely to suffer. This could damage the potential of PAs to substantially contribute to ameliorating the effects of acute medical staff shortages in many specialties and geographical areas served by the UK NHS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank James Grey for his assistance with recruitment and Angelique Dueñas for her thoughtful comments on the draft of this work.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Megan_EL_Brown, @gabs_finn

Contributors: MELB conceived the original research idea, guided by GMF and WL in a supervisory capacity. GMF and WL contributed knowledge of qualitative study design and gave guidance on the execution of the study’s methodology. MELB and WL conducted all data collection. All authors (MELB, WL, PAT and GMF) were involved in data analysis and interpretation. All authors were involved in the drafting and the critical revision of the entire paper, approving the final manuscript for publication, and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Institutional ethical approval was obtained from the Hull York Medical School prior to commencement of this research. Institutional ethical approval was granted prior to data collection.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available. Ethics approval was not obtained to make data sharing possible outside of the listed research team.

References

- 1. NHS England General practice: case studies. The physician associate will see you now- new role to assist patients in primary care [Internet], 2019. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/gp/case-studies/the-physician-associate-will-see-you-now-new-role-to-assist-patients-in-primary-care/ [Accessed 19 Jul 2019].

- 2. Faculty of Physician Associates quality health care across the NHS [Internet]. Fparcp.co.uk, 2019. Available: http://www.fparcp.co.uk/about-fpa/Who-are-physician-associates [Accessed 22 Feb 2019].

- 3. NHS Health Education England. Health Careers. Explore roles: Physician associate [Internet], 2019. Available: https://www.healthcareers.nhs.uk/explore-roles/medical-associate-professions/roles-medical-associate-professions/physician-associate [Accessed 19 Jul 2019].

- 4. Ross N, Parle J, Begg P, et al. . The case for the physician assistant. Clin Med 2012;12:200–6. 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-3-200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. British Medical Association Education, training and workforce: Physician associates in the UK [Internet], 2019. Available: https://www.bma.org.uk/collective-voice/policy-and-research/education-training-and-workforce/physician-associates-in-the-uk [Accessed 19 Jul 2019].

- 6. Department of Health The government response to the house of commons health select Committee report on primary care (fourth report of session 2015-16. London: Department of Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Drennan VM, Halter M, Joly L, et al. . Physician associates and GPs in primary care: a comparison. Br J Gen Pract 2015;65:e344–50. 10.3399/bjgp15X684877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drennan VM, Halter M, Wheeler C, et al. . What is the contribution of physician associates in hospital care in England? a mixed methods, multiple case study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e027012 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Halter M, Wheeler C, Pelone F, et al. . Contribution of physician assistants/associates to secondary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019573 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. NHS England General Practice Forward View [Internet]. England.nhs.uk., 2019. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/gpfv/ [Accessed 22 Feb 2019].

- 11. NHS Digital General Practice Workforce, General Practice Workforce Final 31 March 2019, experimental statistics [Internet]. Available: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/general-and-personal-medical-services/final-31-march-2019-experimental-statistics [Accessed 18 Sept 2019].

- 12. Ritsema TS. Faculty of physician associates census results. [Internet], 2018. Available: http://www.fparcp.co.uk/about-fpa/fpa-census [Accessed 18 Sep 2019].

- 13. Centre for professional qualifications Professions : Regulated Professions [Internet], 2019. Available: https://www.naric.org.uk/cpq/professions/regulated%20professions/default.aspx [Accessed 19 Jul 2019].

- 14. Department of Health and Social Care, The regulation of medical associate professionals in the UK: consultation response. London: Department of Health and Social Care, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Royal College of Physicians Faculty of Physician Associates. General Medical Council announced as regulator for physician associates, [Internet], 2019. Available: https://www.fparcp.co.uk/news/general-medical-council-announced-as-regulator-for-physician-associates [Accessed 19 Jul 2019].

- 16. Health Education England Annual report and accounts 2017/18. London: Health Education England, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holden M, Buck E, Clark M, et al. . Professional identity formation in medical education: the convergence of multiple domains. HEC Forum 2012;24:245–55. 10.1007/s10730-012-9197-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Freedman D, Stoddard Holmes M. The teacher's body. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sabancıogullari S, Dogan S. Effects of the professional identity development programme on the professional identity, job satisfaction and burnout levels of nurses: a pilot study. Int J Nurs Pract 2015;21:847–57. 10.1111/ijn.12330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hall DT, Zhu G, Yan A. Career creativity as protean identity transformation : Peiperl M, Arthur M, Anand N, Career creativity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002: 159–79. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hafferty FW, Cruess RL, Cruess SR, et al. . Professionalism and the socialization of medical students. teaching medical professionalism. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2009: 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Monrouxe LV. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Med Educ 2010;44:40–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03440.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weaver R, Peters K, Koch J, et al. . ‘Part of the team’: professional identity and social exclusivity in medical students. Med Educ 2011;45:1220–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Joseph K, Bader K, Wilson S, et al. . Unmasking identity dissonance: exploring medical students’ professional identity formation through mask making. Perspect Med Educ 2017;6:99–107. 10.1007/s40037-017-0339-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boudreau JD, Macdonald ME, Steinert Y. Affirming professional identities through an apprenticeship: insights from a four-year longitudinal case study. Acad Med 2014;89:1038–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. de Lasson L, Just E, Stegeager N, et al. . Professional identity formation in the transition from medical school to working life: a qualitative study of group-coaching courses for junior doctors. BMC Med Educ 2016;16:165 10.1186/s12909-016-0684-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dornan T, Pearson E, Carson P, et al. . Emotions and identity in the figured world of becoming a doctor. Med Educ 2015;49:174–85. 10.1111/medu.12587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sundberg K, Josephson A, Reeves S, et al. . May I see your ID, please? an explorative study of the professional identity of undergraduate medical education leaders. BMC Med Educ 2017;17 10.1186/s12909-017-0860-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, et al. . A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med 2015;90:718–25. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schneller ES. The Physician’s Assistant: Innovation in the Medical Division of Labor. Lexington Books, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maxwell J. Chapter 3: Conceptual Framework: What do you think is going on? : publications S, Qualitative research design: an interactive approach. applied social research methods series. 2nd edn Thousand Oaks, CA, 2005: 33–64. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded theory. London: Sage Publications, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morse J. Situating grounded theory within qualitative inquiry : Schreiber R, Stern P, Using grounded theory in nursing. New York: Springer Publishing Company, 2001: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Trede F, Macklin R, Bridges D. Professional identity development: a review of the higher education literature. Stud High Educ 2012;37:365–84. 10.1080/03075079.2010.521237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge Univeristy Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lave J. Situating learning in communities of practice : Resnick L, Levine J, Teasley S, Perspectives on socially shared cognition. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1991: 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med 1994;69:861–71. 10.1097/00001888-199411000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Williams J. Constructing a new professional identity: career change into teaching. Teach Teach Educ 2010;26:639–47. 10.1016/j.tate.2009.09.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Volpe RL, Hopkins M, Haidet P, et al. . Is research on professional identity formation biased? early insights from a scoping review and metasynthesis. Med Educ 2019;53:119–32. 10.1111/medu.13781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Takahashi K, Bertino E. Identity management. Boston, Mass: Artech House, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wenger E. Communities of practice. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bulei I, Dinu G. From identity to professional identity- a multidisciplinary approach. Proceedings of the 7th international management conference: new management for the new economy; 2013; Romania. International management conference website: International management conference, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Williams LE, Ritsema TS. Satisfaction of doctors with the role of physician associates. Clin Med 2014;14:113–6. 10.7861/clinmedicine.14-2-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Drennan VM, Gabe J, Halter M, et al. . Physician associates in primary health care in England: a challenge to professional boundaries? Soc Sci Med 2017;181:9–16. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McCartney M. Margaret McCartney: Are physician associates just "doctors on the cheap"? BMJ 2017;359:j5022 10.1136/bmj.j5022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jackson B, Marshall M, Schofield S. Barriers and facilitators to integration of physician associates into the general practice workforce: a grounded theory approach. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e785–91. 10.3399/bjgp17X693113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gill D. Becoming Doctors: The Formation of Professional Identity in Newly Qualified Doctors [PhD]. University of London, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Turner TH, Collinson SR, Fry HS. Doctor in the house: the medical student as academic, attendant and apprentice? Med Teach 2001;23:514–6. 10.1080/01421590126489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Densen P. Challenges and opportunities facing medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 2011;122:48–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Boston University Physician Assistant Program—MS. [Internet], 2019. Available: https://www.bu.edu/academics/gms/programs/physician-assistant/ [Accessed 8 Nov 2019].

- 51. Jakobsen F, Hansen TB, Eika B. “Knowing more about the other professions clarified my own profession”. J Interprof Care 2011;25:441–6. 10.3109/13561820.2011.595849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Adams K, Hean S, Sturgis P, et al. . Investigating the factors influencing professional identity of first-year health and social care students. Learning in Health and Social Care 2006;5:55–68. 10.1111/j.1473-6861.2006.00119.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hood K, Cant R, Leech M, et al. . Trying on the professional self: nursing students' perceptions of learning about roles, identity and teamwork in an interprofessional clinical placement. Appl Nurs Res 2014;27:109–14. 10.1016/j.apnr.2013.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Costello CY. Changing clothes: gender inequality and professional socialization. NWSA J 2004;16:138–55. 10.2979/NWS.2004.16.2.138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Costello CY. Professional identity crisis: race, class, gender and success at professional schools. Nashville TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2005: 1–264. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Parkman A. The imposter phenomenon in higher education: incidence and impact. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice 2016;16:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wenger E. Conceptual tools for CoPs as social learning systems: boundaries, identity, trajectories and participation. in: social learning systems and communities of practice. London: Springer, 2010: 125–43. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Christmas S, Cribb A. How does professional regulation affect the identity of health and care professionals: exploring the views of professionals, professionals standards authority, 2017. Available: https://www.professionalstandards.org.uk/docs/default-source/publications/research-paper/professional-identity-and-the-role-of-the-regulator-overview.pdf?sfvrsn=dc8c7220_4 [Accessed 22 Feb 2019].

- 59. Smith DT, Jacobson CK. Racial and gender disparities in the physician assistant profession. Health Serv Res 2016;51:892–909. 10.1111/1475-6773.12358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033450supp001.pdf (33.9KB, pdf)