Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the association of the discharge medicines review (DMR) community pharmacy service with hospital readmissions through linking National Health Service data sets.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

All hospitals and 703 community pharmacies across Wales.

Participants

Inpatients meeting the referral criteria for a community pharmacy DMR.

Interventions

Information related to the patient’s medication and hospital stay is provided to the community pharmacists on discharge from hospital, who undertake a two-part service involving medicines reconciliation and a medicine use review. To investigate the association of this DMR service with hospital readmission, a data linking process was undertaken across six national databases.

Primary outcome

Rate of hospital readmission within 90 days for patients with and without a DMR part 1 started.

Secondary outcome

Strength of association of age decile, sex, deprivation decile, diagnostic grouping and DMR type (started or not started) with reduction in readmission within 90 days.

Results

1923 patients were referred for a DMR over a 13-month period (February 2017–April 2018). Provision of DMR was found to be the most significant attributing factor to reducing likelihood of 90-day readmission using χ2 testing and classification methods. Cox regression survival analysis demonstrated that those receiving the intervention had a lower hospital readmission rate at 40 days (p<0.000, HR: 0.59739, CI 0.5043 to 0.7076).

Conclusions

DMR after a hospital discharge is associated with a reduction in risk of hospital readmission within 40 days. Linking data across disparate national data records is feasible but requires a complex processual architecture. There is a significant value for integrated informatics to improve continuity and coherency of care, and also to facilitate service optimisation, evaluation and evidenced-based practice.

Keywords: health informatics, information technology, health services administration & management, health policy, organisation of health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to explore patient data linkage to investigate the association of a postdischarge intervention in community pharmacy with hospital readmissions.

Pseudonymised data were made identifiable and linked across multiple national databases.

The data linkage failed to record patients’ access of any other healthcare services, such as the general practitioner, following discharge.

Even though this was a retrospective observational cohort study, we addressed potential for bias by confounder adjusted analysis.

No investigation was carried out in this study on the barriers and facilitators of activation of discharge medicines review part 1, via an implementation science lens.

Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that medicines-related errors and adverse events can occur at points of patients transitioning between healthcare settings.1–4 Internationally, numerous interventions have been designed and delivered to try and address this eventuality, with the aim to reduce medicines-related, preventable hospital readmissions. A recent systematic review has found that interventions involving a community pharmacist after hospital patients are discharged home, demonstrate capacity to identify and rectify medicine-related problems, which could have resulted in avoidable hospital admission.5 In June 2019, the National Health Service (NHS) in England committed to introduce a postdischarge medicines reconciliation service through community pharmacies by 2024.6

Currently in the UK there are three main transfer-of-care technologies or services, whereby community pharmacists contribute to the medicines reconciliation process posthospital discharge: (1) Refer-to-Pharmacy, an online platform adopted in East Lancashire that refers patients along with discharge information from hospital for postdischarge medicines support through the community pharmacy, as judged appropriate by the community pharmacist, for example, targeted medicine use reviews7 8; (2) PharmOutcomes, an online portal widely used in community pharmacies across England that allows hospitals to upload discharge information, which can then be transmitted and accessed by community pharmacists to provide postdischarge support services9 10; and (3) discharge medicines review (DMR) service, used across Wales, which integrates the referral of patient hospital discharge information to community pharmacies with a two-stage service including identifying discrepancies between the first prescription postdischarge and the discharge advice letter, followed up by a supportive medication review focused on adherence.11

A service evaluation in 2016 aimed to assess if a new transfer-of-care service implemented from hospitals in the North East of England that involved patients being referred to a nominated community pharmacy on discharge for follow-up care led to reduced hospital readmissions.9 Patient referrals in the hospital were generated using PharmOutcomes; hospital pharmacy staff were required to input patient data since there was no interconnectivity with the electronic NHS patient record at that time. Community pharmacy staff were then completing intervention and outcome data on the PharmOutcomes platform. The evaluation showed that this service was associated with significantly reduced patient readmissions to hospital in 30, 60 and 90 days and shorter length of hospital stay if they were readmitted.9 However, PharmOutcomes is not used nationally across England, and outcome data completed by community pharmacists were not networked back to the hospital where the referral was generated. Due to this disjointed information flow, retrieving data about subsequent hospital readmissions and length of hospital stays required access of another database with steps of deanonymisation and reanonymisation to match data in PharmOutcomes with data in the hospital admission records.

The DMR service is a two-part, community pharmacist-led service introduced in Wales in 2011 to support patients with their transition from one care setting to another. The service has mainly been used for patients recently discharged from hospital and transitioning back into the home environment.11 The aim, as with the transfer-of-care service in the North East, is to reduce the risk of preventable medicines-related problems, improve adherence with newly prescribed medicines, and improve patient knowledge and use of medicines. This service is operationalised employing electronic platforms and developed interoperability to generate a referral from the hospital to a nominated community pharmacy. Part 1 of the service is a medicines reconciliation between the medications listed in the first prescription from the general practitioner (GP) after discharge and the discharge medication list, including rectifying any unintended discrepancies that have arisen. The rectification of these discrepancies may involve contact with the patient or carer, GP or the hospital to gather the most relevant information. Part 2 is a medicines use review that gives the pharmacist an opportunity to discuss any medicines-related issues with the patients, including adherence, dosing and side effects. Evaluation of the DMR service has shown positive outcomes, including the identification of 1.15–1.3 discrepancies per service completed and an average threefold return on financial investment.12 13 After the initial evaluation confirmed the benefits of the service,12 it was rolled out nationally, currently being available in 703 community pharmacies in Wales. The evaluations focused on cost benefit and identifying discrepancies in the medicines’ reconciliation process. However, to date, there has been no formal process of linking data from the DMR service to hospital data with a subsequent evaluation of the association of DMR with patient readmission to hospital.

Linking data sets from different divisions in the NHS has been reported to be limited, and it is widely acknowledged that NHS data are not used effectively to guide patient care.14 The aim of this study was to explore the use of national routine data linkage to investigate the association of DMR with patient hospital readmission.

Methods

Intervention description

The independent evaluation undertaken in 2014 provides a description of the DMR service in Wales12; however, it is briefly outlined here to provide a contextual background.

Pharmacists in a total of 703 out of 716 community pharmacies in Wales are currently completing DMRs with the support of Choose Pharmacy, a national web-based application that supports the delivery of NHS advanced and enhanced community pharmacy services. Accredited community pharmacies and community pharmacists can access via Choose Pharmacy an electronic discharge advice letter (eDAL) generated by the medicines transcribing and electronic discharge (MTeD) functionality in the National Welsh Clinical Portal, to support an electronic DMR. Patients are linked to the Welsh Demographic Service and matched to existing health records, enabling collection of demographic information such as gender and age. When an eDAL is generated, the patient’s nominated community pharmacy receives a notification via the Electronic NHS Alert Service that one of their patients has been discharged from hospital. In the event a patient has been discharged from a non-MTeD ward and has received a paper discharge advice letter, a physical copy needs to be taken to the pharmacy for DMR to be initiated. Choose Pharmacy is still used to record the DMR undertaken.

Patients are identified and recruited to the DMR service either by referral from a healthcare professional during their hospital stay or following their discharge by patients self-referring, by their nominated carer presenting in the pharmacy or by the pharmacist when necessary criteria are met.

Patients are eligible for the service when the following criteria are met:

The patient’s medicines have been changed during their hospital stay.

The patient is taking four or more medicines.

The patient’s medicine requires dispensing into a multicompartment compliance device.

The pharmacist has, in their professional opinion, reason to consider that the patient would benefit from the service.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome in this study was the rate of hospital readmission within 90 days for patients with and without a DMR part 1 started. The secondary outcome was the strength of association of age decile, sex, deprivation decile, diagnostic grouping and DMR type (started or not started) with rate of readmission within 90 days.

Routine data collection

Six data sources were used for this study, with data obtained via the NHS Wales Informatics Service (NWIS) for the period of February 2017–April 2018 (table 1).

Table 1.

Description of the type of data collected and stored in the national databases in Wales that were used in the data linkage in this study

| National data source in Wales | Overview |

| Choose Pharmacy | A national web-based application that supports the delivery of NHS advanced and enhanced community pharmacy services in Wales. Holds data for all services completed in the pharmacy in the form of clinical information and predefined answers, including data for all electronic DMRs that were completed using Choose Pharmacy. |

| Patient Episode Database for Wales | A system that records all episodes of inpatient and day case activity in NHS Wales hospitals, which include planned and emergency admissions, minor and major operations, and hospital stays for giving birth. |

| Admitted Patient Care Data Set | Captures data for all consultant-led admitted patient activity, regardless of the patient’s area of residence. NHS Digital provides data on Welsh resident or registered patients treated in English NHS organisations. Once admitted, a patient may have several episodes within a hospital stay. Only once an episode is complete or the hospital spell ends will it be captured in the Admitted Patient Care Data Set. |

| Office of National Statistics death notifications database | Annual data on deaths registered by age, sex and selected underlying cause of death. |

| Welsh Demographics Service | Provides the demographic characteristics of people registered with GP practices in Wales. The Welsh Demographics Service maintains a register of Welsh residents’ demographic details, including name, address, date of birth, general practice and NHS number. For any consultations completed via Choose Pharmacy, patients are linked to the Welsh Demographic Service and matched to existing health records, enabling collection of demographic information. |

| National Data Resource | A resource currently being developed to better enable NHS Wales to improve patient experience and service outcomes. The National Data Resource aims to deliver a more joined-up approach to health and care data, using common language and technical standards and providing improved analytics capability. |

DMRs, discharge medicines reviews; GP, general practitioner; NHS, National Health Service.

Data linkage

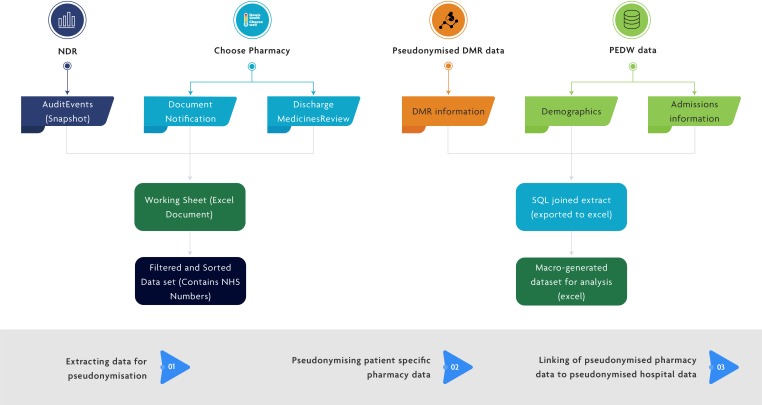

Hospital data were available for all patients who were referred for the service on hospital discharge, selected by clinical staff based on one or more of the DMR criteria. The data linkage process was completed in three steps and ensured that pseudonymised data from individuals could be linked together to provide a picture of the patient’s journey without patient identifiable information being shared (figure 1):

Figure 1.

Information flow diagram depicting the architecture required to link all required patient data to investigate hospital readmission outcome data for those offered a DMR service. DMR, discharge medicines review; NDR, National Data Resource; PEDW, Patient Episode Database for Wales; SQL, Structured Query Language.

Step 1: extracting data for pseudonymisation: records for pseudonymisation were identified when a patient was referred from a hospital to a community pharmacy for a DMR.

Step 2: pseudonymising patient-specific pharmacy data: the pseudonymisation process involved the encryption of the patient’s NHS number to create an anonymous linking field (ALF), which was assigned to each record.

Step 3: linking of pseudonymised pharmacy data to pseudonymised hospital data: the ALF was used to link these records to the pseudonymised identifiable patient records in hospitals, which have been assigned with the same ALF.

Information from these data sets was used to create a new data set for analysis, which included whether the pseudonymised patient had received the DMR service, admission information such as their age, deprivation quintile, diagnosis, length of stay before they were referred into the DMR service, and the same admission information for the first admission occurring after referral to the DMR service. The full process for the data linkage is shown in online supplementary table 1.

bmjopen-2019-033551supp001.pdf (114KB, pdf)

Ethical considerations

Data collection at the first instance was part of routine collection of information when the patient visits a healthcare setting. Patients provided informed consent when offered the DMR service as part of routine hospital and community pharmacy care. This consent covers the recording of data and any processing or preprocessing to a form (by NWIS), for the purpose of service activity, audit and evaluation, in an identifiable way. Records-based research was then completed that did not involve people directly.

The NWIS Head of Information Governance approved the methodology and helped set the criteria for processing the information to ensure patient privacy was maintained in all circumstances. The model of processing and data linkage was consistent with the NWIS trusted third-party responsibilities and is used in many circumstances to ensure confidentiality, integrity and availability of information, in line with guidance for use of secondary data and criteria set by the General Medical Council in relation to anonymisation and risk of de-identification.15 16

Data analysis

Secondary data analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel for descriptive statistics and Stata Special Edition 14.2 and R (using the partykit and survival libraries) for more complex statistical analyses. In order to ensure that there was sufficient time following referral to capture data about a patient being readmitted, all referrals after 31 December 2017 (which is 90 days prior to the last date in the data extract) were removed from the data set. The denominator for the calculations was all inpatients referred for a DMR, the intervention group was those who activated part 1 of the DMR, and the comparator was those referred for a DMR but who did not activate it.

Pearson’s χ2 test, using a significance level of 0.05, was applied to records of all patients offered a DMR who did not die within 90 days of their discharge, to assess whether the DMR changed the probability of readmission and evaluate how likely it is that any observed difference between the sets arose by chance. The χ2 test has a null hypothesis that there is no association between whether a patient had started a DMR (had completed at least part 1 of the service) and whether they were readmitted within 90 days. All patients who had died before 90 days after the notification had been sent were removed from this analysis, in line with literature,17 18 as these deaths could skew the results (eg, if a patient died within 90 days without readmission, they would be recorded as ‘no readmission within 90 days’, which would be an inappropriate classification).

A conditional inference tree (CTree) was produced to look at which patient traits had the strongest association with whether a patient was readmitted within 90 days. CTrees partition cohorts by selecting successive splits in variables with the strongest association to the outcome of interest, as measured by p values, and have previously been used in health service research.19 20 CTree is a non-parametric class of regression trees embedding tree-structured regression models into a well-defined theory of conditional inference procedures; it uses a statistical theory (selection by permutation-based significance tests) in order to select variables instead of selecting the variable that maximises an information measure (Gini coefficient or information gain) and thereby removes the potential bias in Classification and Regression Trees (CART) or similar decision trees.21 In this case, the CTree used gender, deprivation decile, age decile, diagnosis grouping (eg, respiratory, circulatory) and whether a DMR had been started to look at the relationship of these with readmission within 90 days. A significance level of 0.05 was used.

To better understand the probability of readmission over time, the Kaplan-Meier estimator was used to estimate the likelihood of readmission for a patient who had started a DMR versus a patient who had not been provided a DMR over specified time intervals. The inverse of the Kaplan-Meier curve was created to describe the likelihood of readmission, based on avoidance of readmission.

A Schoenfeld residual test for non-proportional hazards was used to test the proportional hazards assumption.22 To adjust for the findings of this test, we created a time stratified Cox regression survival analysis using age, sex, diagnosis, deprivation and DMR as variables. We used a step function (time-dependent coefficient) model, using a stratification time we chose based on a plot of the Aalen model.23 We have looked at the HR confidence intervals to combat the possible issues with type 1 error and to better estimate the association between DMR use and readmission.

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist for cohort studies was used to guide the reporting of this study and is shown in online supplementary table 2.

bmjopen-2019-033551supp002.pdf (81.1KB, pdf)

Patient involvement

Patients were not involved in the design or conduct of this study.

Results

A total of 1923 records were available within the specified time period (February 2017–April 2018), up to 90 days prior to the last date in the data extract available. There was a small number of cases where some data were not recorded in the system (36 patients with blank diagnosis, 1 with missing deprivation quintile). These have been removed for all analyses except for Kaplan-Meier.

Primary outcome

A total of 244 records referred to patients who died within 90 days of a notification being sent; 79 of these patients died prior to any readmission. In order to eliminate any skew caused by patients who were not readmitted but died, the 79 records were removed for all χ2 and conditional inference analyses. Therefore, a total of 1844 records were used, with 673 (36.5%) of those records referring to patients receiving the DMR service, representing the intervention cohort.

A statistically significant difference was identified at the 90-day readmission rate of those patients who had started a DMR and those who had not received a DMR (Pearson’s χ2=23.0829) (p<0.001). This implies there was an association between when a DMR had been started and readmission within 90 days, and based on the rates of readmission we conclude that readmission was less likely (table 2). The characteristics of the baseline population of the study (n=1923), split into groups in relation to whether they had received DMR part 1 service on discharge from hospital, are presented in online supplementary table 3.

Table 2.

Number of patients offered a DMR service who did not die (n=1844) and went on to receive the service, by whether there was a hospital readmission within 90 days of discharge

| Patient group | Readmission within 90 days n (%) |

No admission within 90 days n (%) |

Total n (%) |

| DMR started | 307 (31.4) | 366 (42.2) | 673 (36.5) |

| No DMR | 670 (68.6) | 501 (57.8) | 1171 (63.5) |

| Total | 977 | 867 | 1844 |

DMR, discharge medicines review.

bmjopen-2019-033551supp003.pdf (43.9KB, pdf)

The CTree used to identify the variable with the strongest association to readmission within 90 days used age decile, sex, deprivation decile, diagnostic grouping and DMR type (started or not started) as the possible criteria for classification. This identified that the variable with the strongest association was whether the patient had started a DMR or not (p<0.001) (online supplementary figure 1). Just over 40% of those who had started a DMR were readmitted within 90 days, compared with just under 60% of those who did not have a DMR. Among those who had started a DMR, the next statistically significant association was age (p~0.035). Those in the 20–29, 40–49, 50–59 and 60–69 age brackets had a readmission rate within 90 days of just over 30%, whereas other ages had a readmission rate within 90 days of around 50%. If a DMR had not been started, gender was the factor with the next strongest association with readmission within 90 days (p<0.001).

bmjopen-2019-033551supp004.pdf (102.4KB, pdf)

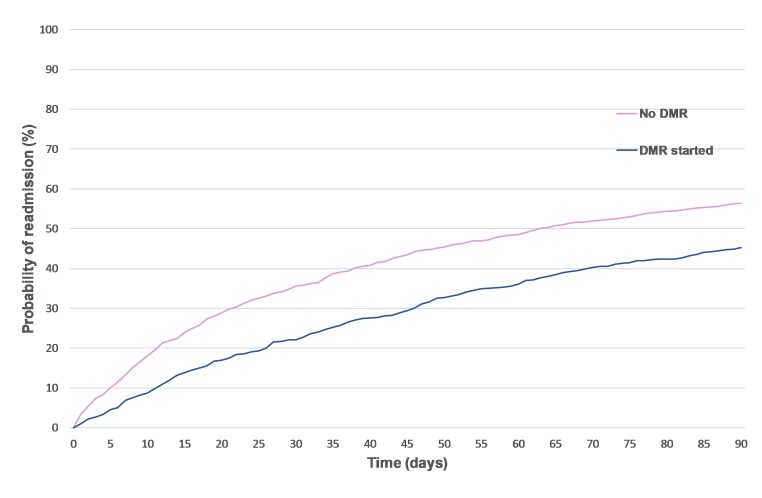

To further investigate this, the inverse of the Kaplan-Meier estimator was produced by completing survival analysis (with patients who died acting as censored data) and demonstrated that the patient group who had received a DMR had a lower hospital readmission rate at 30 (22% vs 36 %), 60 (36% vs 49%) and 90 (45% vs 56%) days postdischarge, as illustrated in the inverse of the Kaplan-Meier curve in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Survival analysis looking at the probability of readmission postdischarge for patients who had started a discharge medicines review (DMR) service compared with those who had not, over time.

To build on this survival analysis, a time stratified Cox survival analysis was used with a stratification of the DMR variable at 40 days, identified by plotting DMR using the Aalen model. The only variable triggering the significance tests when we ran the survival analysis was the stratified DMR variable from 0 to 40 days. This variable had an HR of 0.59739 with a CI underneath 1 (0.5043 to 0.7076). This suggests that readmission within 40 days is less likely when a DMR has been started. Online supplementary table 4 presents the full results on p values for each variable.

bmjopen-2019-033551supp005.pdf (62.9KB, pdf)

Secondary outcomes

The CTree suggested that sex may also be associated with reduction of readmission within 90 days for patients without a DMR. However, the results of the Cox survival analysis showed no significant associations other than with DMR, with HRs that do not show any consistent effect from any of the other variables (online supplementary table 5). This could indicate that further tests should be done to model processes for patients who have started a DMR and those with no DMR separately when more data are available in order to understand where this discrepancy comes from.

bmjopen-2019-033551supp006.pdf (60.6KB, pdf)

Discussion

This is the first published study, to our knowledge, using a range of national databases to link routine service activity and patient data from community pharmacy and hospital, at a national level, to investigate the association with hospital readmissions. The analysis of the linked data has facilitated three methods for checking whether the DMR intervention had an association with readmission. This process has demonstrated that those patients who had started a DMR were significantly less likely to be readmitted within 90 days than those who had no DMR provision. The DMR intervention was also found to be the factor most associated with reduced readmissions within 40 days when conducting multivariate survival analysis to better estimate the independent association between DMR and readmission.

Results from this study support published literature that community pharmacist postdischarge interventions have positive outcomes on patient care. In a recent systematic review looking at pharmacist-led medication reconciliation at patient discharge, only 30% of the studies described a patient discharge plan, and in only 14% of cases information of the patient’s medication was shared with community pharmacists.24 The DMR service provides a structured approach to information sharing, overcoming the major organisational-level and individual-level factors affecting the medication reconciliation process,25 and an opportunity for a face-to-face discussion and counselling with the patient to account for their changing needs postdischarge. Literature reports that patients’ information needs are individual, and even when counselled by hospital pharmacists only half of the patients could recall information related to medication changes.26 Unlike other systems in the UK, the DMR service is available nationally across Wales, and from April 2020 a new functionality will become available in the system, so that outcome data completed by community pharmacists will be available to view in the hospital where the referral was generated.

We have found that the DMR service has a more prominent association with patient readmission rates than reported in previous work. This contributes to the body of evidence around community pharmacy services or interventions that may reduce hospital readmissions, thereby supporting delivery of government initiatives to promote the Care Closer to Home agenda.27 The role of community pharmacists in seamless primary care services has been recognised in the Strategic Programme for Primary Care and with the Welsh Government having recently announced their support to community pharmacists and committed financially to a sustainable, appropriately trained workforce to deliver extended services.28–30

The primary outcome data align well with that previously published in the North East England transfer-of-care service,8 9 which also demonstrated a significant decrease in readmissions for patients receiving postdischarge community pharmacy care. Both studies share the limitation that the data linkage fails to record patients’ access of any other healthcare services, such as the GP, following discharge, which exists as a potential confounder to the results. This means that findings presented here, similar to those of Nazar et al,8 9 are that of correlation rather than a direct casual consequence.

Another recent study adopting consensus methodology aimed to identify appropriate referral criteria of inpatients to be offered this type of follow-up care. Age was not a factor rated most highly by expert panel members (ie, top 3); however, it was recognised as a potential parameter to consider.13 31 Our findings infer that patients aged 50–79 years fare best in terms of reduced hospital readmissions when offered the DMR service; however, the small numbers of patients across all age groupings limit the validity of this deduction. The debate around the targeting of these types of postdischarge services is therefore still warranted to understand which patients benefit most significantly towards optimising service efficiency and effectiveness.

The process of data linking depicted here illustrates the complexity in the information technology (IT) healthcare system, which poses challenges for health service providers, commissioners, evaluators and researchers. Work commissioned by the King’s Fund recently reported that the key contributing barriers to the provision of clinical services within community pharmacies in the UK are isolation from the central healthcare system and lack of digital interoperability.14 32 The Minister for Health and Social Services in Wales has set the plans to develop a National Data Resource (NDR) as part of a ‘Statement of Intent’ to better use health and care data in October 2017. It aims to deliver linked, longitudinal data for both direct patient care and healthcare analysis and research. NDR will drive forward the interoperability of health and care systems, ultimately delivering benefit across the healthcare economy to patients, clinicians, operational managers and policy makers.

Within England, there has been much attention in the past decade on shared electronic patient records, the Summary Care Record (SCR). This was introduced in 2009 as part of the National Programme for IT by the Department of Health to provide a mechanism to improve communication and connectedness between many healthcare sectors of the NHS. The sharing of such a record aims to facilitate safe, appropriate and tailored care provision for patients from wherever they may be accessing it.31 33 An independent evaluation in 2010 raised a number of concerns about complexity, technical challenges, workload and information governance. This has also been accompanied by slower than anticipated uptake and faced controversy, both in the public and professional arenas.32 34 Recently, announcements have been made that the SCR will be phased out by 2024 and will be replaced with local health and care records that will combine GP, hospitals, and other health and social care information.33 35 The data will be anonymised within the NHS and therefore facilitate evaluation and research. This proposal is a development towards improving evidence-based practice, which requires appropriate and supportive informatics infrastructure. Bakken36 contests that evidence to underpin clinical practice should be broadly conceptualised as a continuum of synthesised information, ranging from the ‘gold standard’ of randomised controlled trails, to aggregated data from individual practice of a clinician or experiences of individual patients. In establishing an integrated, longitudinal patient care record, evidence-based practice will be facilitated by the building of evidence from clinical practice and its outcomes.34 However, in the interim, SCR uptake and access have been patchy, with little published evidence of facilitating evaluation and research agendas to investigate health outcomes as a consequence of interventions.

This was a pragmatic observational cohort study, with enrolment into the DMR based on clinician judgement, and as such no power calculation could have been performed and there was a large potential for bias. However, we tried to estimate the effect size using HR in the survival analysis and we addressed this bias as far as possible with confounder adjusted analysis and by exploring the possibility of residual confounding.

Although we have tried to take into account some socioeconomic indicators (i.e. deprivation decile), we have not investigated whether those who have started a DMR are more health conscious than those who are not, so some of the effect seen here may be indicative of some patient activation or other related external factors, as yet unmeasured. Barriers to community pharmacists undertaking follow-up reviews postdischarge have recently been reported in the literature. Elson et al 37 explored patients’ knowledge of new medicines after discharge from hospital and identified that fewer than half of the patients who were allocated to receive a community pharmacy medicines review received one. Further work will involve exploring factors that support or inhibit activation of part 1 of the DMR via an implementation science lens.

Conclusion

Evidence supporting systems that identify and enact on unintended discrepancies after patient discharge from hospital is already widely available; this study demonstrates that the DMR service has a more prominent association with patient readmission rates than reported in previous work. This adds to the body of evidence that continuity of care on discharge and transfer of care should be prioritised as a global patient safety challenge, to achieve a 50% reduction in minimising medication safety issues, stated as a target in a recent WHO report on tackling medication-related harm.38

Despite the current challenging nature of linking NHS data collected across a range of organisations, it is possible to use linked data effectively to not only improve continuity and coherency of care, but also to facilitate service optimisation, evaluation and evidenced-based practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Haseeb Fazili of NHS Wales Informatics Service for his support in preparing figure 1.

Footnotes

Twitter: @efi_mantz, @NazarHamde, @AndrewEvansCPhO

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published. The affiliation for Dr Hamde Nazar has been updated.

Contributors: EM, AE, CW and KH conceptualised the study. EM designed and managed the study, and coordinated data collection and linkage. EM and HN were involved in the data interpretation, manuscript preparation and final submission. CP, JP and GJ completed the data analysis and linkage. HT provided guidance on ethical considerations around data linkage and supported data collection across the national databases. All authors were involved in reviewing versions of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The project was submitted to the Research and Development office of Velindre University NHS Trust as the legal entity responsible for the conduct of studies within NWIS, the organisation that holds all the data we required for this study. It was confirmed that an application to an NHS Research Ethics Committee was not required, and that the study should be conducted ensuring regulatory compliance in line with established NWIS policies and procedures. Throughout the study we liaised with the Head of Information Governance of NWIS to ensure this.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data can be shared upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Hesselink G, Schoonhoven L, Barach P, et al. Improving patient handovers from hospital to primary care: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:417–28. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-6-201209180-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Braund R, Coulter CV, Bodington AJ, et al. Drug related problems identified by community pharmacists on hospital discharge prescriptions in New Zealand. Int J Clin Pharm 2014;36:498–502. 10.1007/s11096-014-9935-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mansur N, Weiss A, Beloosesky Y. Relationship of in-hospital medication modifications of elderly patients to Postdischarge medications, adherence, and mortality. Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:783–9. 10.1345/aph.1L070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thompson-Moore N, Liebl MG. Health care system vulnerabilities: understanding the root causes of patient harm. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2012;69:431–6. 10.2146/ajhp110299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nazar H, Nazar Z, Portlock J, et al. A systematic review of the role of community pharmacies in improving the transition from secondary to primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015;80:936–48. 10.1111/bcp.12718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. NHS England and NHS Improvement A short summary of the community pharmacy contractual framework for 2019/20 to 2023/24: supporting delivery for the NHS long term plan. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/short-summary-community-pharmacy-contractual-framework.pdf

- 7. Gray AH. Refer‐to‐Pharmacy: benefits and early outcomes. Prescriber 2016;27:38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clark C. Transfer of care: how electronic referral systems can help to keep patients safe. Pharm J 2016;297:7891. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nazar H, Brice S, Akhter N, et al. New transfer of care initiative of electronic referral from hospital to community pharmacy in England: a formative service evaluation. BMJ open 2016;6:e012532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ramsbottom HF, Fitzpatrick R, Rutter P. Post discharge medicines use review service for older patients: recruitment issues in a feasibility study. Int J Clin Pharm 2016;38:208–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mantzourani E, Way CM, Hodson KL. Does an integrated information technology system provide support for community pharmacists undertaking discharge medicines reviews? an exploratory study. Integr Pharm Res Pract 2017;6:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hodson KL, Blenkinsopp A, Cohen D, et al. Evaluation of the discharge medicines review. independent report, 2014. Available: http://www.cpwales.org.uk/Contract-support-and-IT/Advanced-Services/Discharge-Medicines-Review-(DMR)/Evaluation-of-the-DMR-Service/Evaluation-of-the-DMR-service.aspx [Accessed 01 Jul 2019].

- 13. Hodson K. A four-year evaluation of the discharge medicines review service provision across all Wales. FIP Congress 2018.

- 14. The Health Foundation Data linkage: joining up the dots to improve patient care, 2018. Available: https://www.health.org.uk/newsletter-feature/data-linkage-joining-up-the-dots-to-improve-patient-care [Accessed 12 Dec 2019].

- 15. General Medical Council Using and disclosing patient information for secondary purposes, 2019. Available: https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/confidentiality/using-and-disclosing-patient-information-for-secondary-purposes [Accessed 7 Dec 2019].

- 16. Eynden Vden, Corti L, Woolard M, et al. Uk data Archive. managing and sharing research data, 2011. Available: https://ukdataservice.ac.uk/media/622417/managingsharing.pdf [Accessed 6 Dec 2019].

- 17. Clark TG, Bradburn MJ, Love SB, et al. Survival analysis Part I: basic concepts and first analyses. Br J Cancer 2003;89:232–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singh R, Mukhopadhyay K. Survival analysis in clinical trials: basics and must know areas. Perspect Clin Res 2011;2:145–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.pp.Hartney M, Liu Y, Velanovich V, et al. Bounceback branchpoints: using conditional inference trees to analyze readmissions. Surgery 2014;156:842–8. 10.1016/j.surg.2014.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sardá-Espinosa A, Subbiah S, Bartz-Beielsteinb T. Conditional inference trees for knowledge extraction from motor health condition data. Eng Appl Artif Intel 2017;62:26–37. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hothorn T, Hornik K, Zeileis A. Unbiased recursive partitioning: a conditional inference framework. J Comput Graph Stat 2006;15:651–74. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang Z, Reinikainen J, Adeleke KA, et al. Time-Varying covariates and coefficients in COX regression models. Ann Transl Med 2018;6:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rickert J. Survival analysis with R, 2017. Available: https://rviews.rstudio.com/2017/09/25/survival-analysis-with-r/ [Accessed 1 Dec 2019].

- 24. Fernandes BD, Almeida PHRF, Foppa AA, et al. Pharmacist-Led medication reconciliation at patient discharge: a scoping review. Res Social Adm Pharm. In Press 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.08.001. [Epub ahead of print: 01 Aug 2019]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kennelty KA, Chewning B, Wise M, et al. Barriers and facilitators of medication reconciliation processes for recently discharged patients from community pharmacists' perspectives. Res Social Adm Pharm 2015;11:517–30. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2014.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eibergen L, Janssen MJA, Blom L, et al. Informational needs and recall of in-hospital medication changes of recently discharged patients. Res Social Adm Pharm 2018;14:146–52. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. NHS The NHS long term plan, 2019. Available: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/nhs-long-term-plan-june-2019.pdf [Accessed 12 Dec 2019].

- 28. Strategic programme for primary care, 2018. Available: http://www.primarycareone.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/documents/1191/Strategic%20Programme%20for%20Primary%20Care.pdf [Accessed 25 Nov 2019].

- 29. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society Pharmacy: delivering a healthier Wales, 2019. Available: https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Policy/Pharmacy%20Vision%20English.pdf?ver=2019-05-21-152234-477 [Accessed 25 Nov 2019].

- 30. Gething V. Written statement: Welsh government support for community pharmacies, 2019. Available: https://gov.wales/written-statement-welsh-government-support-community-pharmacies [Accessed 12 Dec 2019].

- 31. Nazar H, Maniatopoulos G, Mantzourani E, et al. Consensus methodology to investigate appropriate referral criteria for inpatients to be offered a transfer of care service as they are discharged home. Integr Pharm Res Pract 2019;8:35–7. 10.2147/IPRP.S190008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Murray R. Community pharmacy clinical services review. London: NHS England, 2016: 16. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Greenhalgh T, Wood GW, Bratan T, et al. Patients’ attitudes to the summary care record and HealthSpace: qualitative study. BMJ 2008;336:1290–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Greenhalgh T, Stramer K, Bratan T, et al. Adoption and non-adoption of a shared electronic summary record in England: a mixed-method case study. BMJ 2010;340:c3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maguire D, Evans H, Honeyman M. Digital change in health and social care. King's Fund, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bakken S. An informatics infrastructure is essential for evidence-based practice. JAMIA 2001;8:199–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Elson R, Cook H, Blenkinsopp A. Patients' knowledge of new medicines after discharge from Hospital: what are the effects of hospital-based discharge counseling and community-based medicines use reviews (MURs)? Res Social Adm Pharm 2017;13:628–33. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sheikh A, Dhingra-Kumar N, Kelley E, et al. The third global patient safety challenge: tackling medication-related harm. Bull World Health Organ 2017;95:546 10.2471/BLT.17.198002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033551supp001.pdf (114KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033551supp002.pdf (81.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033551supp003.pdf (43.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033551supp004.pdf (102.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033551supp005.pdf (62.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033551supp006.pdf (60.6KB, pdf)