Abstract

Introduction

This protocol outlines the rationale, design and methods for the process and feasibility evaluations of the primary care management on knee pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis (PARTNER) study. PARTNER is a randomised controlled trial to evaluate a new model of service delivery (the PARTNER model) against ‘usual care’. PARTNER is designed to encourage greater uptake of key evidence-based non-surgical treatments for knee osteoarthritis (OA) in primary care. The intervention supports general practitioners (GPs) to gain an understanding of the best management options available through online professional development. Their patients receive telephone advice and support for OA management by a centralised, multidisciplinary ‘Care Support Team’. We will conduct concurrent process and feasibility evaluations to understand the implementation of this new complex health intervention, identify issues for consideration when interpreting the effectiveness outcomes and develop recommendations for future implementation, cost effectiveness and scalability.

Methods and analysis

The UK Medical Research Council Framework for undertaking a process evaluation of complex interventions and the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) frameworks inform the design of these evaluations. We use a mixed-methods approach including analysis of survey data, administrative records, consultation records and semistructured interviews with GPs and their enrolled patients. The analysis will examine fidelity and dose of the intervention, observations of trial setup and implementation and the quality of the care provided. We will also examine details of ‘usual care’. The semistructured interviews will be analysed using thematic and content analysis to draw out themes around implementation and acceptability of the model.

Ethics and dissemination

The primary and substudy protocols have been approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of The University of Sydney (2016/959 and 2019/503). Our findings will be disseminated to national and international partners and stakeholders, who will also assist with wider dissemination of our results across all levels of healthcare. Specific findings will be disseminated via peer-reviewed journals and conferences, and via training for healthcare professionals delivering OA management programmes. This evaluation is crucial to explaining the PARTNER study results, and will be used to determine the feasibility of rolling-out the intervention in an Australian healthcare context.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12617001595303; Pre-results.

Keywords: primary care, model of service delivery, process evaluation, clinical trial, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A comprehensive, preplanned, process and feasibility evaluation of a complex model of service delivery.

Mixed-methods approach, underpinned by theoretical frameworks for design and evaluation of complex health interventions and chronic disease management.

Codesigned by a broad range of stakeholders including general practitioners, people with osteoarthritis, physiotherapists, rheumatologists, industry groups and policy makers.

Outcomes from this study will directly contribute to the implementation priorities of the Australian ‘National Osteoarthritis Strategy’.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading cause of lower limb pain and disability, affecting more than 2 million Australians.1 Although there is no cure, there are effective non-surgical treatments for the long-term management of symptomatic OA.2 In particular, education and advice on OA, exercise and physical activity and weight management are the core interventions recommended by current clinical guidelines.3–5 These treatments are, however, often underutilised in primary care, and day-to-day management of Australians with knee OA is inconsistent with these recommendations.6 We designed the Effectiveness of a new model of primary care management on knee pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis (PARTNER) study, to address this issue.7 The aim of the PARTNER study is to test a new model of service delivery (the PARTNER model), designed to encourage greater uptake of these key non-surgical treatments in primary care pathways, in comparison to usual care.

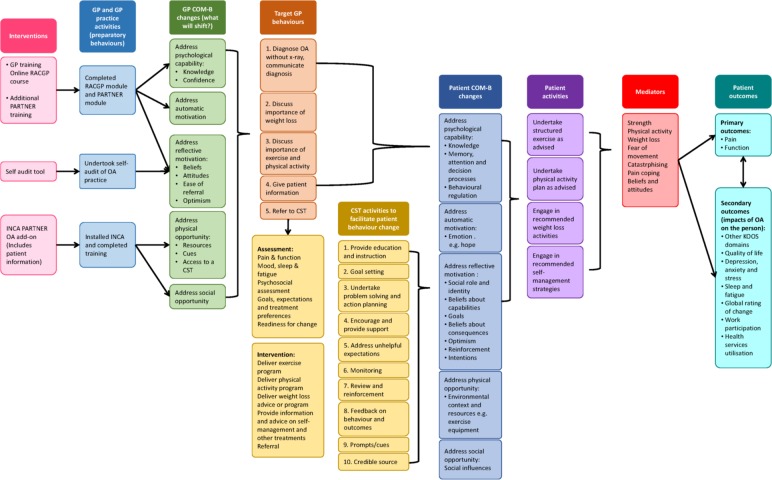

The PARTNER model is a complex health intervention (figure 1) employing multiple interacting components that target different organisational levels of healthcare delivery.8 The intervention will target both general practitioners (GPs) and their patients with OA. GPs will be provided with online professional development opportunities to gain an understanding of the effective conservative, non-surgical management options available for treatment of patients with OA and endorsed by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Their patients will receive tailored advice and support on issues related to the management of OA including physical activity and exercise, weight loss, pain management and other effective self-management behaviours. This support will be delivered remotely for 12 months by a centralised, multidisciplinary ‘Care Support Team’ (CST) of health professionals trained in best-practice management of OA and health behaviour change.

Figure 1.

The PARTNER logic model. Theoretical basis for the development of the PARTNER model of service delivery, and the mechanisms underpinning the process evaluation. COM-B, capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour; GP, general practitioner; INCA, integrated care management software (formally cdmNET); PARTNER, primary care management on knee pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis; RACGP, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners.

The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of this new model is being tested through a two-arm, cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT), and the process and feasibility evaluations described here will be conducted concurrently with the RCT. These evaluations will help us to understand the factors influencing the implementation of the intervention, identify issues for consideration when interpreting the effectiveness results and enable us to develop recommendations for future implementation of the new model into Australian general practice. This process evaluation and feasibility protocol has two aims, namely:

-

To explain the PARTNER study results in terms of fidelity and engagement with the intervention, and determine:

1.1. Whether the intervention and control arms were delivered as intended for both the GPs and patients enrolled in the study.

1.2. What ‘usual care’ entailed, including types and rate of uptake of other services recommended for the patient.

1.3. The types of issues typically identified or actioned during the consultations between the participants and the healthcare professionals in the study (ie, the GPs and CST), and determine the nature of the support and advice provided for each issue.

1.4. Participants’ (GPs and patients) and the CST personnel’s perspectives on how, why and for whom the intervention did or did not work.

1.5. Whether the primary and secondary outcome effects were due to the nature of the implementation, or to the intervention.9

-

To determine the feasibility and acceptability of having the model adopted broadly in an Australian healthcare context (if the study is found to be effective), specifically:

2.1. Are there potential barriers and enablers to rolling the model out in the Australian primary care setting that have not been identified previously? We will look at barriers and enablers at the patient level, professional, organisational and service level (meso) and health systems level (macro).10

2.2. Do people with OA, and GPs, value the intervention as it was delivered?

2.3. Are the results generalisable to other people with OA, healthcare service providers and to different Australian healthcare contexts (eg, public or private hospitals).

2.4. Is the intervention cost effective compared with usual care?

Methods and analysis

The PARTNER cluster RCT

The PARTNER study is an investigator-initiated pragmatic RCT. A detailed explanation of the background, theoretical development and protocol for the broader PARTNER study (2016/959) has been described previously,7 11 and the trial prospectively registered with the Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12617001595303). The process and feasibility evaluations will be reported in accordance with the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies, and the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines.12 13

Briefly, the RCT is comparing the new PARTNER model of service delivery to usual care.7 We will recruit 44 general practices and 572 patients with knee OA in urban and regional practices in Victoria and New South Wales, Australia. The patients will be 45 years of age or older, and have had knee pain (≥4/10) for a minimum of 3 months. The model has interventions for both the person with OA, and their GP. The GP intervention will provide professional development and training opportunities on the most current conservative, non-surgical management options available for OA, as recommended by national and international clinical guidelines.3–5 This will include audit/feedback activities, online learning modules and the Integrated Care electronic desktop IT support tool (previously named cdmNET). All GPs in the study regardless of group allocation will be asked to provide an initial evidence-based consultation for their participating patients. If allocated to the intervention arm, patients will be referred to the PARTNER CST. The CST is a centralised, multidisciplinary team of health professionals trained in best-practice OA management, and with skills in health behaviour change. The CST will support patient participants to manage their knee OA for a period of 12 months. The CST will provide the patients with education, advice and ongoing support for behaviour change on the key OA treatments, including leg strengthening exercises, general physical activity, weight loss and appropriate use of pain medications as agreed with the patient. Patients with a body mass index ≥27 will have the option of completing the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation’s online ‘Total Wellbeing Diet’ (TWD) program.14 15 The TWD program is based on an evidence-based, structured, nutritionally balanced eating plan designed to be delivered as part of a balanced lifestyle programme.16 Patient participants may also be directed to one or more secondary interventions or additional healthcare services if they meet the referral criteria and/or have identified it as a personal priority. These treatment options may include online cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) programme for mood, pain coping and sleep or referrals to healthcare professionals (eg, physiotherapists or dieticians) for face-to-face sessions. The primary outcomes of the PARTNER study are change in self-reported pain and function at 12 months. We will also assess a range of secondary patient-level outcomes at 6 and 12 months, and including the cost-effectiveness of the model.7

Patient and public involvement

One of the strengths of this process and feasibility evaluation is that it has been incorporated into the overall study design from conception. Both the main protocol and this evaluation and feasibility subprotocol are underpinned by existing theoretical frameworks.17–21 It has built on considerable background work undertaken by our team, and with input from a broad range of stakeholders, GPs and consumers who participated in our five working groups: (1) scientific methods, (2) data, (3) GP model of service delivery, (4) consumer engagement and (5) policy and marketing. Each working group was chaired by an appropriate representative from either an industry partner, consumer group or other stakeholder organisation. This process and feasibility evaluation protocol has had further input from colleagues with expertise in implementing and assessing health interventions, and its content has evolved after findings from our pilot work. We send 6 monthly updates on the study’s progress to our stakeholders and participants via an online newsletter.

Theoretical frameworks for the process evaluation

Figure 1 outlines the PARTNER logic model, which summarises the key questions, target behaviours, interventions, mediators and outcomes for both GPs and patients recruited to the study. The development of the model used Wagner’s theoretical framework for the management of chronic disease,17 the Behaviour Change Wheel and the Theoretical Domains Framework18 to identify key intervention components and propose a causal pathway between the study intervention and the main outcomes.

Our methods for the process and feasibility evaluations are based on the recommendations from the UK Medical Research Council framework for undertaking a process evaluation of complex interventions.19 The RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance) framework has further guided the development of our evaluation questions.20 21 RE-AIM is recommended by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International for conducting implementation trials on OA.9 RE-AIM emphases the need to look into the proportion and representativeness of the participants’ involved in the trial, the impact of the intervention, the fidelity and dose of the implementation and identify issues impacting on long-term scaling of the model. It covers five domains, briefly:

Reach: did the intervention reach who we intended?

Effectiveness: was the intervention effective and cost-effective? (this question is primarily addressed by the RCT)7

Adoption: who do we need to target to develop institutional support for the intervention? Did the practices recruited to our study adopt the changes at an organisational level, how representative were these sites compared with other Australian settings and what needs to be undertaken to have it adopted more widely? Will actual change in the way OA is managed in primary care be achievable with our model, and how well do the end users (clinicians, patients and other service providers) accept the intervention and processes?9

Implementation: was the intervention delivered correctly and consistently (fidelity) as intended at the trial outset?

Maintenance: can the intervention be delivered sustainably in different healthcare contexts and more broadly?

Data sources for the PARTNER study

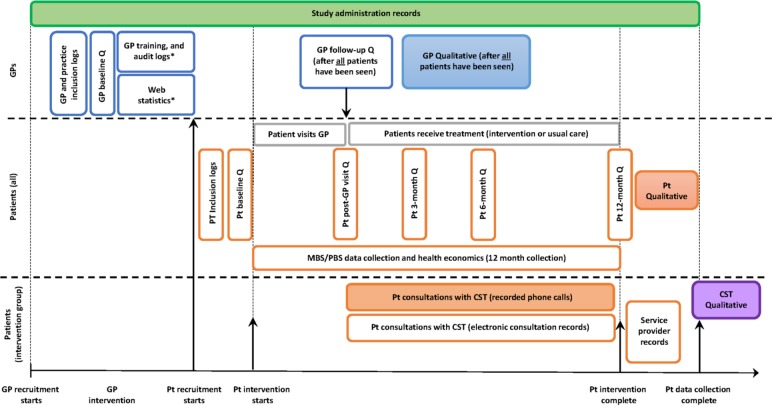

We will use a mixed-methods approach that uses both quantitative and qualitative methods to capture process data for analysis (table 1, figure 1), all of which involve informed consent and have been approved by an ethics committee. Detailed descriptions of the quantitative data collection instruments and analysis have been described previously in the main protocol,7 with details relevant to this protocol outlined below. The type and timing of data collected to address each aim of the process evaluation, including the details of the qualitative data collection are described in the following sections. Figure 2 illustrates the integration of the process and feasibility evaluations with the main RCT. Briefly, the data collection methods and time points relevant to these evaluations include:

Table 1.

Data collection methods used to address each aim and question of the process evaluation

| Aims | Data collection method | |||||

| i | ii | iii | iv | v | vi | |

| Aim 1: Explain the trial results in terms of fidelity and engagement: | ||||||

| 1.1 Were the intervention and control arms delivered as intended: | ||||||

| GPs | X | X | X | X | ||

| Patients | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| CST | X | X | ||||

| 1.2 What did ‘usual care’ entail? | ||||||

| GPs | X | X | ||||

| Patients | X | X | ||||

| 1.3 What types of issues were discussed or actioned during the interactions between the CST/GPs and the patients? | ||||||

| GPs | X | X | ||||

| CST | X | X | X | X | ||

| 1.4 Participants and healthcare professionals’ perspectives on how, why and for whom the interactions did or did not work? (semistructured qualitative interviews). | ||||||

| GPs | X | |||||

| CST | X | |||||

| Patients | X | |||||

| 1.5 Were the primary and secondary outcome effects due to the nature of the implementation or to the intervention? | ||||||

| GPs | X | X | ||||

| Patients | X | X | X | X | ||

| Aim 2: Feasibility and acceptability of scaling the intervention in Australia | ||||||

| 2.1 What are the possible barriers and enablers to rolling-out the model in Australian primary care? | ||||||

| GPs | X | X | ||||

| Patients | X | X | ||||

| 2.2 Do patients and GPs value the intervention as delivered? | X | |||||

| GPs | X | |||||

| Patients | X | |||||

| 2.3 Are the results generalisable to other patients with OA, healthcare service providers and across states? | ||||||

| X | X | |||||

| 2.4 Is the intervention cost-effective compared with usual care? | ||||||

| Patients | X | X | X | |||

i. Analysis of inclusion / exlusion criteria, screening logs and withdrawal logs.

ii. Analysis of the quantitative data collected in electonic surveys for both the GPs and patients with OA.

iii. Analysis of a sample of recorded telephone interactions between the CST responsible for providing the intervention and the patients with OA

iv. Audit of data collected over the trial (the electronic consultation notes) that captures the number, length and nature of the interactions between the CST and patients with OA.

v. Semi-structured interviews with patient participants and the GPs and CST involved in the study.

vi. Audit of training logs and other activity logs for GPs in the intervention group. This includes analysis of web usage statistics.

Figure 2.

Indicative timing of the data collection processes for GPs and patients. This schematic illustrates the integration of the process and feasibility evaluations with the main RCT. Open boxes are quantitative data collection, filled boxes are qualitative data (interviews or phone call recordings). The patient intervention is for 12 months. *Data are collected for GPs in the intervention group only. CST, Care Support Team; GPs, general practitioners; Pt, patients; Q, online survey questionnaires.

Study administration records: include participant tracking, screening, training, withdrawal and serious adverse event logs; and training logs for the GPs, CST and other trial staff. Data are collected for the duration of the trial.

Electronic survey data from patients and GP surveys. GPs complete surveys at baseline and after the study team has confirmed all their patients have attended their first GP consultation. Patients complete surveys at baseline, post GP visit, 3, 6 and 12 months.

Electronic consultation detailed records of each of the CSTs’ consultations with the intervention patients over the 12-month period.

Service provider records will be collected from external providers delivering the weight-loss intervention, and the online CBT programme offered to the intervention group (ie, painTrainer and ThisWayUp).

Recorded consultation phone calls between the patient and the CST: all patient consultations for the duration of the patient’s involvement with the CST will be audio-recorded. For the first 18 weeks patients will be contacted once a fortnight on average (nine calls), and then monthly for the next 6 months (six calls). The actual number and timing of these calls will be agreed between the patient and the CST.

Semistructured qualitative interviews: these will be undertaken with a selection of GPs, patients and the CST personnel. GP interviews will be undertaken after all their enrolled patients have had their initial GP visit. Patient interviews will be undertaken after they have completed their 12-month survey. The CST interviews will be undertaken after all patients have finished their last consultation.

Quantitative data analysis to address the aims of the process evaluation

We will use a wide selection of the quantitative data to explain the study’s effectiveness results in terms of fidelity and engagement with the intervention, particularly around the consistency of the study’s implementation as per the primary protocol (figure 1) and the trial procedures manuals (Aim 1.1). This will include the study administration records, the electronic survey data collected from both patients and GPs, the electronic consultation records from the CST and any changes required to the protocol over the duration of the study. For the GPs in the intervention group, we will also examine how many completed the required professional development training modules, the optional capacity building training modules and the number of intervention patients who were ultimately referred to the CST with OA (ie, if there were any patients who were not diagnosed with OA). We will further examine if patients have reported receiving information on, or discussed with their GP, any of the four key topics (OA education, physical activity, muscle strengthening and weight loss), and whether OA management plans were prepared for each patient. To determine what usual care entailed for our control cohort (Aim 1.2), we will analyse the electronic survey data from both the GPs and patients, including if there were any unanticipated treatments prescribed or activities undertaken that may need to be addressed in a future roll-out of the model.

For the CST, we will analyse the study records and survey data to determine the amount of time spent with each patient, and whether the key interventions or secondary interventions (mood, pain and sleep management) were discussed in the consultations. Electronic patient survey data, the CST electronic consultation records and a selection of the recorded patient consultations will be further examined to establish what issues or topics were typically discussed during the consultations (Aim 1.3), including any additional issues that may need to be incorporated into the intervention long-term (also see the Qualitative data collection methods section). We will examine the nature of the support and advice provided to patients by both the GPs and the CST, map the frequency and accuracy of each treatment component to the international care standards for OA (OA Quality Indicators)22 23 and identify any conflicting advice that may need to be addressed when designing future training or educational materials.

We will also use the quantitative datasets to determine the feasibility and acceptability of having the model adopted broadly in an Australian healthcare context. We will explore healthcare providers’ and patients’ experience of the intervention and its perceived impact (Aim 2.2 and 2.3) and examine any issues that arose during the trial that would affect broader implementation (Aim 2.1). We will undertake an audit of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the screening logs for general practices, GPs and patients to identify any reasons for not choosing to participate and for any loss to follow-up. These data will be compared with the general population to give an indication of the representativeness and generalisability of the results to other patients, healthcare service providers and other Australian states/territories. Collectively, these data will provide some insight into the generalisability of the efficacy results, and any amendments that may need to be incorporated into the current model. This information will also be used to determine the cost effectiveness of the PARTNER model compared with usual care.7

Qualitative data collection

In addition to the quantitative datasets, we will collect and analyse qualitative data that will address many of the process and feasibility aims of this study (see table 1). First, we will analyse a sample of the telephone interactions that have been recorded between the patients in the intervention group and the CST. After the final patient is recruited, we will purposively select 20 patients to conduct a detailed analysis of their telephone consultations. We aim to ensure maximum heterogeneity of sampling, based on clinical and demographic characteristics, and gain the perspectives of patients and GPs in both urban and regional/rural general practices and smaller versus larger practices. To capture the change in the perspectives over the 12 months, three phone calls will be analysed per person, covering the initial consultation—one randomly selected call from the first 18 weeks of the intervention (intensive phase), and one randomly selected call from the last 6 months of the CST intervention (maintenance phase). The phone recordings will be transcribed and analysed using predesigned checklists. The first checklist will be used to determine how much time is spent on the key priority topics and the targeted secondary interventions (mood, pain coping and sleep; figure 1). A tally will be made of the different types of issues discussed during the calls and the type of information given (Aim 1.1, 1.3, 1.5). We will also assess if the components of care delivered by the CST are accompanied by the appropriate behaviour change methods to support self-management as per the PARTNER protocol. We will use a checklist based on the methodology developed by our partner ‘HealthChange Australia’ to train the CST in behaviour change techniques to examine the fidelity of the delivery of the behaviour change component of the intervention. This analysis will be undertaken by a member of the study team involved with the intervention, and an independent person not involved with running the trial. Data will be compiled and compared, and if required adjudicated by a third party.

Second, we will undertake semistructured qualitative interviews with a selection of patients, GPs and the CST. These results will also address a range of the aims of these process and feasibility evaluations (table 1), and a primary focus on contextual factors affecting delivery and implementation, and thus those that influence rolling-out and long-term sustainability of the PARTNER model (Aims 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3). The interviews will be conducted over the telephone or face-to-face, by dedicated researcher/s not involved with delivering the RCT and with experience in qualitative data collection. Our multidisciplinary research team will develop the semistructured interviews to explore issues around patients’, GPs’ and CST personnel’s perspectives on how, why and for whom the interventions did or did not work, positive and negative (unintentional) outcomes, possible barriers and facilitators to rolling-out the intervention, including any adoption considerations at the setting or organisational (meso) level, if the new model of care is valued by the users, and if they found any aspects burdensome (ie, the number of appointments for patients or the amount of training for GPs).

Similar to the selection of recorded CST phone consultations, we will use purposive sampling to gain perspectives from patients and GPs from different regional and practice-related contexts. This will include around 30 patients (15 control and 15 intervention) and 14 GPs (7 from each group), or until redundancy is observed. We will also interview all willing members of the CST. Patients will be different from those used in the examination of the telephone consultations with the CST and will have finished their involvement with the trial. The interviews will be conducted one-to-one and will take approximately 1 hour each. Participants will be consented by the interviewer over the phone. The interviews will follow an interview guide which outlines the broad discussion topics. The draft interview schedule will be tested with patients and healthcare professional volunteers prior to use.

Qualitative data analysis plan

The semistructured interview data and content data will be thematically analysed and interpreted. Interviews will be audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts will be coded and analysed thematically, using methods of constant comparison derived from grounded theory.24 Contextual information derived from other process data will be used to triangulate the identified themes. The logic model (figure 1) and process evaluation framework (table 1) will aid the analysis by triangulating the quantitative data with the relevant qualitative data under each subheading. Qualitative data analysis software ‘NVivo’ (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) will be used. Identified themes will be explored, looking for shared or disparate views among the patients, GPs and CST about their experiences of participation, implementation and operationalisation of the study at their practice (if relevant). The collection and analysis of the qualitative data will be conducted iteratively so that themes identified in early interviews can be explored in more depth later.19

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol outlines the rationale, design and methods for process and feasibility evaluations of the PARTNER study, a RCT designed to test the new PARTNER model of service delivery. This evaluation of a complex intervention is crucial to explaining the PARTNER study results, and to determine the feasibility of scaling the intervention in an Australian healthcare context. The data and results will be used to identify and address issues in the intervention and improve the delivery of the model long-term, with a focus on effectiveness, quality and safety and scalability.

Outcomes from this study, regardless of the effectiveness of the RCT, will directly contribute to the implementation priorities of the Australian ‘National Osteoarthritis Strategy’,25 the aligned jurisdictional Models of Care in Western Australia,26 New South Wales27 and Victoria,28 and other associated national strategies.4 29 The National OA strategy has multi-partisan support from peak and professional bodies, governments, private health insurers and consumers to improve access to evidence-based, non-surgical OA interventions that deliver high-value care to all Australians with OA. It specifically calls for the prioritisation of testing and implementation of new models of service delivery to support referral to allied health and community-based services, assist primary care practitioners to deliver essential lifestyle-based interventions and ultimately reduce the over-reliance on medications and joint replacement surgery. Our findings will be disseminated to all partners and stakeholders involved with both the study’s initial design, and those with an interest in its long-term implementation. The National OA Strategy Leadership Group and Implementation Advisory Committee will help drive dissemination of our results across all levels of healthcare to address the local, meso and macro needs identified. At an international level our results will contribute to the work of the Osteoarthritis Research Society International’s ‘Joint Effort Initiative’ who are currently developing broadscale guidelines and recommendations to assist with the global implementation of OA management programs.30 Specific research findings will be disseminated via peer-reviewed journals and conferences, and we anticipate delivering training workshops for interested healthcare professionals.

In conclusion, this paper reports the design of the mixed-methods process and feasibility evaluations for the PARTNER study. The results will help us gain a better understanding of the implementation of the intervention and identify issues for consideration when interpreting its effectiveness. However, these evaluations will also allow us to identify any broader issues or considerations that will need to be addressed for a wider roll-out of this new model of service delivery in Australian primary care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

DJH is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowship (APP1079777). RSH is supported by a NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (#1154217). MP has been supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship. KLB is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Principal Research Fellowship. We wish to acknowledge the contribution of all our stakeholders, working groups, partner organisations and their representatives in the design of the PARTNER model and this study, in particular Ms Franca Marine and Ms Ainslie Cahill, Arthritis Australia

—educational materials and advice. Ms Jeanette Gale and Ms Caroline Bills, HealthChange Australia—training for the CST and provision of manuals. Professor Michael Georgeff and Dr Marienne Hibbert, Precedence Health Care—INCA software and training. Dr Kevin Cheng, Ms Rebecca Bell and Ms Sonia Dixon, Medibank Private. Ms Natalie Dubrowin, Bupa Australia. The PARTNER CST: Hayley Morey, Joanne Bolton, Kim Allison, Kelly Woosnam, Jane Evans, Liz Dixon, Chris Yeomans and Heidi Williams. The PARTNER Study Team: Karen Schuck, Charlotte Marshall, Stephanie Hawkins, Michelle King, Rebecca Doyle, Janet Cook, Carin Pratt, Iqbal Hasan and Anna Wood.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ProfDavidHunter

Contributors: KLB, RSH and DJH conceived the initial project and procured the project funding, and DJH is leading the trial. KLB, RSH, DJH and TE developed the primary study protocol, and JLB led the further development of the process evaluation and feasibility protocol. AMB, SJB, SDF, JK, MP, DJS, and NAZ assisted with both protocol designs. JLB wrote the first and final draft of this manuscript. All authors participated in the trial design, provided feedback on drafts and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by a 3 year NHMRC partnership grant (APP1115720) of the Australian Government. The NHMRC has had no role in the design or other components of the study except for funding. The study is cofunded by our Private Health Insurer partner organisations; Medibank Better Health Foundation and Bupa Australia who declare an interest in the outcome. We are receiving further in-kind support, resources and services from Arthritis Australia, Medibank Private, Good2Give, Monash University, Precedence Health Care and HealthChange Australia. The NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence for Translational Research in Musculoskeletal Pain (APP1079078) have provided additional funding and in-kind support for components of the study outside the scope of the NHMRC grant.

Competing interests: DJH provides consulting advice to Pfizer, Lilly, Merck Serono and TLC bio. SJB is an employee of Medibank.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The primary study protocol (2016/959), this substudy protocol (2019/503), study documents and all subsequent amendments have been approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of the University of Sydney. The study underwent peer-review from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) before receiving funding, and the protocol was prospectively registered with the Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12617001595303).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Hunter DJ, Schofield D, Callander E. The individual and socioeconomic impact of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014;10:437–41. 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meneses SRF, Goode AP, Nelson AE, et al. Clinical algorithms to aid osteoarthritis guideline dissemination. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016;24:1487–99. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Osteoarthritis: care and management in adults. London: NICE, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners Guideline for the management of knee and hip osteoarthritis. 2nd edn East Melbourne: RACGP, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5. McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:363–88. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Runciman WB, Hunt TD, Hannaford NA, et al. CareTrack: assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia. Med J Aust 2012;197:100–5. 10.5694/mja12.10510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hunter DJ, Hinman RS, Bowden JL, et al. Effectiveness of a new model of primary care management on knee pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis: protocol for the partner study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018;19:132 10.1186/s12891-018-2048-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Allen KD, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Foster NE, et al. OARSI Clinical Trials Recommendations: Design and conduct of implementation trials of interventions for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015;23:826–38. 10.1016/j.joca.2015.02.772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blyth FM, Briggs AM, Schneider CH, et al. The global burden of musculoskeletal Pain—Where to from here? Am J Public Health 2019;109:35–40. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Egerton T, Nelligan R, Setchell J, et al. General practitioners’ perspectives on a proposed new model of service delivery for primary care management of knee osteoarthritis: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2017;18:85 10.1186/s12875-017-0656-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. Standards for reporting implementation studies (STARI): explanation and elaboration document. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013318 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int Journal Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Noakes M, Clifton PM. The CSIRO total wellbeing diet. Australia: Penguin Books, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Noakes M, Keogh JB, Foster PR, et al. Effect of an energy-restricted, high-protein, low-fat diet relative to a conventional high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet on weight loss, body composition, nutritional status, and markers of cardiovascular health in obese women. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:1298–306. 10.1093/ajcn/81.6.1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wyld B, Harrison A, Noakes M. The CSIRO total wellbeing diet book 1: sociodemographic differences and impact on weight loss and well-being in Australia. Public Health Nutr 2010;13:2105–10. 10.1017/S136898001000073X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wagner EH, Bennett SM, Austin BT, et al. Finding common ground: patient-centeredness and evidence-based chronic illness care. J Altern Complement Med 2005;11:S7–15. 10.1089/acm.2005.11.s-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The Behaviour Change Wheel (Behavior Change Wheel) - a guide to designing interventions. 2nd edn London: Silverback Publishing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gaglio B, Phillips SM, Heurtin-Roberts S, et al. How pragmatic is it? lessons learned using Precis and RE-AIM for determining pragmatic characteristics of research. Implementation Sci 2014;9:96 10.1186/s13012-014-0096-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1322–7. 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blackburn S, Higginbottom A, Taylor R, et al. Patient-Reported quality indicators for osteoarthritis: a patient and public generated self-report measure for primary care. Res Involv Engagem 2016;2:5 10.1186/s40900-016-0019-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Edwards JJ, Jordan KP, Peat G, et al. Quality of care for OA: the effect of a point-of-care consultation recording template. Rheumatology 2015;54:844–53. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data. 5th edn London, UK: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Osteoarthritis Strategy Project Group National osteoarthritis strategy. Institute of Bone and Joint Research, University of Sydney, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Department of Health (Western Australia) Service model for community-based musculoskeletal health in Western Australia. Perth: Health Strategy and Networks, Department of Health, Western Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27. NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation Osteoarthritis chronic care program model of care: ACI, NSW government, 2018. Available: https://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/resources/musculoskeletal/osteoarthritis_chronic_care_program/osteoarthritis-chronic-care-program [Accessed 4 Oct 2018].

- 28. Victorian Musculoskeletal Clinical Leadership Group Victorian model of care for osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Melbourne: MOVE muscle, bone & joint health, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arthritis Australia Time to move: osteoarthritis. Sydney: Arthritis Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eyles JP, Hunter DJ, Bennell KL, et al. Priorities for the effective implementation of osteoarthritis management programs: an OARSI international consensus exercise. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019;27:1270–9. 10.1016/j.joca.2019.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.