Abstract

Introduction

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) and vaginal microbiota disruption during pregnancy are associated with increased risk of spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB), but clinical trials of BV treatment during pregnancy have shown little or no benefit. An alternative hypothesis is that vaginal bacteria present around conception may lead to SPTB by compromising the protective effects of cervical mucus, colonising the endometrial surface before fetal membrane development, and causing low-level inflammation in the decidua, placenta and fetal membranes. This protocol describes a prospective case-cohort study addressing this hypothesis.

Methods and analysis

HIV-seronegative Kenyan women with fertility intent are followed from preconception through pregnancy, delivery and early postpartum. Participants provide monthly vaginal specimens during the preconception period for vaginal microbiota assessment. Estimated date of delivery is determined by last menstrual period and first trimester obstetrical ultrasound. After delivery, a swab is collected from between the fetal membranes. Placenta and umbilical cord samples are collected for histopathology. Broad-range 16S rRNA gene PCR and deep sequencing of preconception vaginal specimens will assess species richness and diversity in women with SPTB versus term delivery. Concentrations of key bacterial species will be compared using quantitative PCR (qPCR). Taxon-directed qPCR will also be used to quantify bacteria from fetal membrane samples and evaluate the association between bacterial concentrations and histopathological evidence of inflammation in the fetal membranes, placenta and umbilical cord.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was approved by ethics committees at Kenyatta National Hospital and the University of Washington. Results will be disseminated to clinicians at study sites and partner institutions, presented at conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals. The findings of this study could shift the paradigm for thinking about the mechanisms linking vaginal microbiota and prematurity by focusing attention on the preconception vaginal microbiota as a mediator of SPTB.

Keywords: epidemiology, obstetrics, microbiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This prospective case-cohort study enrols Kenyan women with fertility intent, enabling follow-up and exposure measurement from preconception through pregnancy and the early postpartum period.

Monthly specimen collection during the preconception period allows for examination of the vaginal microbiota close to the time of conception.

Fetal membrane swabs and placental samples are collected at delivery, enabling assessment of the association between detection and concentrations of bacteria in the fetal membranes, inflammation and preterm birth.

A combination of broad-range 16S rRNA gene PCR with next-generation sequencing and quantitative PCR assays provide both the relative and absolute quantities of bacteria in vaginal secretions and in the fetal membranes.

Because this is an observational study, it cannot definitively establish a causal relationship between vaginal bacteria and preterm birth.

Introduction

Globally, approximately 10% of births are preterm (<37 weeks of gestation), but the prevalence can be as high as 18% in low-resource countries.1 Preterm birth and its sequelae are the leading causes of death among children under 5.2 The majority of preterm deliveries are spontaneous preterm births (SPTB).3 The cause of SPTB is often unknown, but up to 40% may be associated with intrauterine infections.3 4 Other risk factors include other infections (urinary tract, sexually transmitted and systemic), sociodemographic characteristics (age, race and education),3 extremes of body mass index,5 periodontal disease,6 interpregnancy interval <6 months, prior SPTB, stress, depression and smoking.3 Further elucidation of the causes may provide insight into novel approaches for reducing SPTB.

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a common vaginal condition characterised by a shift from an optimal Lactobacillus-predominant vaginal microbiota to one characterised by high concentrations of diverse anaerobic species.7 Numerous studies indicate that BV during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of SPTB.8 However, a meta-analysis of clinical trials concluded that while antibiotic treatment prior to 20 weeks gestation successfully treated BV, the risk of SPTB was not substantially reduced.9

Molecular microbiology has transformed the understanding of vaginal microbiota to a broader spectrum of phenotypes ranging from low-diversity Lactobacillus-dominated bacterial communities to a heterogeneous group of high-diversity BV-associated communities.10 11 Studies exploring the relationship between the vaginal microbiota and SPTB have yielded conflicting findings. Some found significant associations between increased species diversity and preterm birth,12–16 while others have not.17–19 In addition, some studies have found that women with a low relative abundance of Lactobacillus species and higher relative abundance of BV-related taxa may be at higher risk of preterm birth.16 19–22 Others found no association between vaginal bacterial community type and preterm birth.12 14 17 Detection and higher concentrations of specific vaginal bacteria have also been associated with preterm birth including Leptotrichia/Sneathia,16 23 BV-associated bacterium 1 (BVAB1),16 23 Megasphaera,23 Gardnerella vaginalis,24 25 Atopobium vaginae,24 TM7-H116 and some Prevotella species.16

A novel hypothesis to explain the lack of success of BV treatment during pregnancy on SPTB risk is that preconception vaginal microbiota may be a more important risk factor for SPTB than vaginal bacteria during pregnancy. Vaginal bacteria present around the time of conception could compromise the protective effects of cervical mucus,26 gaining access to the endometrium before embryo implantation, formation of the cervical mucus plug and development of the fetal membrane. These bacteria could colonise and cause chronic, low-level inflammation in the decidua, placenta, fetal membranes or amniotic cavity.27 28 In this scenario, antibiotic treatment during pregnancy may be too late to influence a woman’s risk of SPTB associated with intrauterine bacteria.

The Microbiota and Preterm Birth Study (MPTB) enrols HIV-negative Kenyan women trying to become pregnant into a prospective case-cohort study to address the following aims:

Compare the species diversity and richness of the vaginal microbiota sampled close to the time of conception in women with SPTB versus term delivery using broad-range 16S rRNA gene PCR and next-generation sequencing.

Compare the presence and concentrations of select bacterial genera/species (based on published data23 and results of Aim 1) using targeted quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays in vaginal specimens sampled close to the time of conception in women with SPTB versus term births.

Perform species-specific qPCR assays on samples collected from fetal membranes and histological examination of membranes and umbilical cord to determine if vaginal bacteria ascend to the upper genital tract and cause inflammation in the fetal membranes and umbilical cord.

Methods and analysis

Study design, setting and timeline

The MPTB Study is a prospective case-cohort study. Eligible women enrol prior to conception and are followed through preconception, pregnancy, delivery, and early postpartum. Participants will be selected into the case-cohort sample as detailed in the Statistical Analysis section. Study sites are located at Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) in Nairobi and at Ganjoni Health Center and Coast Provincial General Hospital (CPGH) in Mombasa.

Enrolment began in Nairobi in April 2017 and Mombasa in April 2018. Preconception enrolment of participants will continue through approximately June 2019 with the last study deliveries occurring in 2021, approximately 18 months after the last enrolment.

Eligibility criteria and recruitment

The target population is HIV-negative women who are currently planning to become pregnant. Additional eligibility criteria include being ≤45 years old, having a menstrual period in the prior 3 months or recently discontinued contraceptive methods that induce amenorrhoea (eg, implant, hormonal intrauterine device), willing to comply with study procedures, and able to provide informed consent. Minors aged 14–17 are eligible if emancipated under Kenyan law. Exclusion criteria include current pregnancy, continuing contraception other than condoms for HIV/sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention, having a depot medroxyprogesterone (DMPA) acetate injection in the last 3 months, history of cervical or uterine surgery (other than caesarean section), known autoimmune disease, antibiotic use in the prior 4 weeks, and history of infertility care-seeking. For women with known HIV-positive male partners, their partner must have an undetectable HIV viral load, or the participant must be taking pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Participants are recruited by study staff or referred by healthcare providers at sites providing reproductive or maternal health services. Women discontinuing contraception for the purpose of becoming pregnant are a key recruitment population.

Study visits and procedures

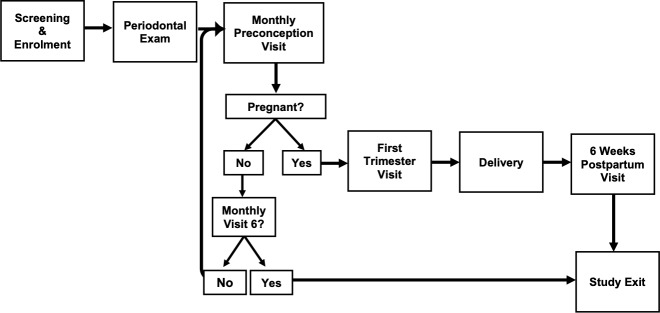

Study participation occurs in six phases including screening/enrolment, periodontal examination, preconception, pregnancy, delivery and postpartum (figure 1). Specimen collection, laboratory testing and other clinical procedures are summarised in table 1.

Figure 1.

Microbiota and Preterm Birth Study Phases—additional participant pathways: (1) Participants who discontinued DMPA injectable contraception within 6 months of study enrolment are eligible for 9 months of preconception follow-up. (2) Participants who miscarry are eligible to re-enter preconception follow-up for a second pregnancy attempt. DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone.

Table 1.

Specimen collection, laboratory testing and other procedures by study visit

| Procedure type | Screening | Enrolment | Periodontal examination | Preconception | 9–12 weeks gestation | Delivery* | Postpartum |

| Specimen collection | |||||||

| Urine pregnancy test | X | X | X | ||||

| Genital swabs | |||||||

| APTIMA swab | X | ||||||

| Push-off swabs† | X | X | X | ||||

| Cotton and Dacron swabs | X | X | X | ||||

| Sialidase test swab | X | X | |||||

| Fetal membrane swab | X | ||||||

| Placental punch | X | ||||||

| Fetal membrane roll | X | ||||||

| Umbilical cord | X | ||||||

| Laboratory testing | |||||||

| HIV rapid test | X | ||||||

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Trichomonas vaginalis | X | ||||||

| Cervical Gram stain | X | ||||||

| Vaginal pH | X | ||||||

| Vaginal wet mount | X | ||||||

| Vaginal Gram stain | X | X | X | ||||

| Lactobacillus culture‡ | X | X | X | ||||

| Sialidase test | X | X | |||||

| PSA test | X | X | X | ||||

| Participant Questionnaires | |||||||

| Eligibility screen | X | ||||||

| Demographics | X | ||||||

| Reproductive history | X | ||||||

| Medical history and current symptoms | X | X | X | ||||

| Sexual behaviour | X | X | X | ||||

| Substance use | X | X | X | ||||

| Dental health history | X | ||||||

| Neonatal heath | X | ||||||

| Obstetric ultrasound | X |

*Delivery follows standard obstetrical procedure and is not conducted by study staff.

†Storing for vaginal microbiota and vaginal inflammatory response testing.

‡Rogosa agar, followed by subculture for hydrogen peroxide production on tetramethylbenzidine agar containing horseradish peroxidase.

PSA, prostate specific antigen.

Screening and enrolment

Following written informed consent for screening, study staff perform urine pregnancy testing and rapid HIV testing according to Kenyan guidelines,29 and conduct an eligibility interview. Eligible women can enrol immediately on consent. If enrolment occurs at a later date, pregnancy testing is repeated to reconfirm eligibility.

Enrollees complete a structured face-to-face interview regarding demographics, sexual behaviour, substance use, depression symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire-9), and reproductive and medical history. A study clinician performs a physical examination and speculum-assisted pelvic examination. If a woman is menstruating, the examination is deferred to avoid sampling during this interval when the vaginal microbiota undergoes rapid changes.30 31 Two vaginal fluid specimens are collected by rolling push-off Dacron swabs (FitzCo) three rotations against the lateral vaginal wall; these are stored for vaginal microbiota and inflammatory response evaluation. Additional genital specimens are collected for STI diagnosis (Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Trichomonas vaginalis by nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT)), vaginal and cervical Gram stains, detection of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and elevated sialidase using a point-of-care diagnostic test for BV (Diagnosit BVBLUE, Gryphus Diagnostics). A vaginal specimen is inoculated onto Rogosa agar for detection of Lactobacillus. Syndromic management is provided as indicated for genital syndromes including vaginal discharge.32 Additional therapy is provided at the first preconception visit based on STI NAAT results.

After the examination, women receive counselling on healthy behaviours during preconception and pregnancy, including smoking cessation, refraining from vaginal washing and a healthy diet. Study clinicians discuss participants’ menstrual cycle and identify the probable fertile window using calendar-based methods. Ovulation is estimated to occur 14 days prior to the first day of the next predicted menses, with the most fertile days emphasised as the 5 days before and day of ovulation.33 All participants receive prenatal vitamins.

Periodontal examination

Periodontitis has been associated with SPTB6 so participants undergo a periodontal examination. Since pregnancy increases gingival inflammation,34 examinations occur within 4 weeks of enrolment. The oral examination includes assessment for periodontitis using periodontal pocket depth and clinical attachment measurements, and the Decay-Missing-Filled Index and Gingival Index assessments.35 Presence and severity of periodontitis are defined using the 2007 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/American Academy of Periodontology case definitions.36 Participants also complete a modified version of WHO’s oral health questionnaire.35

Monthly preconception visits

Participants return for study visits at 1-month intervals while trying to become pregnant. Retention staff call participants in advance of each appointment. A structured interview is conducted to update sexual behaviour and medical history. Women self-collect vaginal swabs for microbiota and inflammatory response analysis, vaginal Gram stain, PSA detection, Lactobacillus culture and sialidase detection. Participants with genital symptoms receive syndromic management.32

A urine pregnancy test is performed, and participants with a positive test are scheduled for a first trimester visit between 9 and 12 weeks of gestation. Most women who remain non-pregnant after 6 months exit the study; those who discontinued DMPA less than 6 months prior to enrolment are eligible for 9 months of preconception ‘trying time’ due to delayed return to fertility after DMPA discontinuation.37 38

First trimester visit (9–12 weeks of gestation)

At the first trimester visit, a structured interview is conducted to update information on sexual behaviour and medical history. Women self-collect vaginal swabs for microbiota and inflammatory response analysis, vaginal Gram stain, PSA detection and Lactobacillus culture. Women then undergo an obstetrical ultrasound to confirm gestational age. The ultrasound is conducted by sonographers at KNH in Nairobi and at a private radiology facility in Mombasa (training and quality control described in table 2). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’s 2014 guidelines are used to estimate gestational age if the ultrasound derived estimate differs from that calculated using the last menstrual period by >7 days before 16 weeks.39 If a later ultrasound is obtained, the sonographic dates are used if they differ from last menstrual period dates by >10 days between 16 and 22 weeks, >14 days between 22 and 28 weeks, and >21 days after 28 weeks.

Table 2.

Periodontal examination, first trimester obstetric ultrasound, and fetal membrane sample training and continuous quality control procedures

| Procedure | Initial training | Continuous quality control procedures |

| Periodontal examination |

|

|

| First trimester obstetric ultrasound |

|

|

| Fetal membrane sample |

|

|

CPGH, Coast Provincial General Hospital; KNH, Kenyatta National Hospital; MPTB, Microbiota and Preterm Birth Study; UoN, University of Nairobi, Nairobi.

Pregnant participants are referred to routine antenatal care (ANC) and enrolled into a short message service (SMS) programme to support retention (see the Retention during pregnancy section). Routinely collected antenatal data (eg, syphilis test results, blood pressure) are abstracted from participants’ ANC facility records and the Mother and Child Health Booklet provided to all pregnant Kenyan women.

If a participant suffers a miscarriage, management of the pregnancy loss is conducted by non-study clinicians according to standard of care. Women who miscarry at <20 weeks of gestation may remain in the study for six additional monthly preconception visits if they would like to try for another pregnancy.

Retention during pregnancy

To improve retention, participants are offered enrolment into an adaptation of a two-way SMS programme that was initially designed to support HIV-positive Kenyan women during pregnancy and postpartum.40 Messages are sent at 16, 20 and 24 weeks gestation, biweekly beginning at 28 weeks, and weekly from 38 weeks through 6 weeks postpartum. In addition, study nurses call participants weekly starting at week 35 to confirm pregnancy status and planned delivery location. Participants are instructed to call at the onset of labour so study staff can coordinate collection of delivery samples for deliveries at KNH or CPGH, and to assist with identification of the delivery date for births occurring elsewhere.

Delivery procedures

Deliveries follow standard obstetrical procedures and are not conducted by study staff. Swabs from between the fetal membranes and placental samples are collected for births occurring at KNH and CPGH by trained labour and delivery nurses (training and quality control described in table 2). On vaginal or caesarean delivery of the placenta, it is placed in a sterile container. Samples are collected as soon as feasible and within 2 hours of delivery. Using sterile technique, a pair of nurses collects samples from between the amnion and chorion.41 A sterile push-off swab (FitzCo) is collected from between the membranes, placed in a cryovial and temporarily stored in a −4°C (Nairobi) or −20°C (Mombasa) freezer. The placenta is placed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. Laboratory staff transport the fetal membrane swab to a −80°C freezer in study laboratories at KNH and CPGH within one working day. Laboratory staff also collect placental samples for histopathology. These include a 4 cm fetal membrane roll from the ruptured edge of the membranes to the edge of the placental disc, a 1 cm section of umbilical cord starting 3 cm from the placental disk, and a 1 cm block of placenta with overlying membranes adjacent to the site of cord insertion. All pathological specimens are stored in 10% neutral-buffered formalin.

Study staff abstract data from delivery records, including type of delivery (ie, vaginal or caesarean; laboured or did not labour; spontaneous or induced labour), complications, live birth or stillbirth, and birth weight.

Postpartum visit

At the 6-week postpartum visit, clinicians abstract any ANC and delivery details not previously captured from the participant’s delivery discharge report and Mother and Child Health Booklet. Participants complete an interview about the infant’s heath and immunisation status.

Incentives

Participants receive KSH300 (about US$3.00) at each study visit. This amount is consistent with other studies in Kenya and is provided to cover transportation costs. Women who become pregnant receive a free obstetrical ultrasound. An incentive of KSH1000 is provided for deliveries at KNH or CPGH.

Laboratory methods

Microscopy, Lactobacillus culture, STI testing and detection of sialidase and PSA in vaginal fluids

Vaginal Gram stained slides are evaluated for BV using the criteria developed by Nugent and Hiller.42 Saline and potassium hydroxide wet mounts are examined for the presence of motile trichomonads, clue cells, yeast and sperm. Endocervical Gram stained slides are scanned at low power, and polymorphonuclear leucocytes in three nonadjacent oil immersion fields are counted and averaged to evaluate cervical inflammation. Clinicians inoculate vaginal specimens directly on Rogosa agar for detection of cultivable Lactobacillus and store the plate in a candle jar until transportation to the laboratory within 4 hours.43 Hydrogen peroxide production is evaluated by subculture of Lactobacillus isolates on tetramethylbenzidine agar containing horseradish peroxidase.44 A vaginal specimen is tested for N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis and T. vaginalis by NAAT (Aptima Combo-2 CT/NG Detection System, Aptima Trichomonas vaginalis assay; Hologic). One vaginal swab is used for detection of sialidase using a commercially available BV diagnostic test (Diagnosit BVBLUE; Gryphus Diagnostics). Testing for PSA in vaginal samples is performed with a commercially available assay (ABAcard, Abacus Diagnostics), which can detect semen for 24–48 hours after condomless sex.45

Molecular methods for identification of bacteria in vaginal and fetal membrane samples

Stored vaginal and fetal membrane swabs for bacterial PCR will be transported on dry ice to the Fredricks Laboratory at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, USA. Qiagen QIAamp BiOstic Bacteremia DNA Isolation Kits (Qiagen, Germantown, Maryland, USA) will be used to extract DNA from vaginal swabs. This protocol uses bead beating and chaotropic lysis to break apart bacterial cells and recover DNA that is free of PCR inhibitors. Swabs that have not contacted a human surface will be processed in parallel to serve as sham DNA extraction (negative) controls. Extracted DNA will be subjected to broad-range 16S rRNA gene PCR using primers that anneal with highly conserved regions of the small subunit rRNA gene, amplifying a 470 base pair segment that contains a highly variable sequence useful for species identification. Bar coded primers will be used to multiplex samples.46 Libraries of 16S rRNA gene amplicons will be mixed for sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform using 300 bp paired-end reads. The assembled reads will be binned into individual study samples using the nucleic acid bar codes. Approximately 10 000–30 000 sequence reads will be generated per sample, providing robust detection of minority species. Raw sequence reads will be demultiplexed using Illumina’s on-board bcl2fastq conversion software V.1.8.4 with zero mismatches in either forward or reverse indices. The DADA2 software package will be used to quality control, filter, pair and cluster the amplicon sequence reads.47 Sequence variants will be assigned taxonomy using the phylogenetic placement tool pplacer48 and a custom vaginal reference set.11 Sham extraction controls will also be processed in parallel to exclude bacterial contamination of reagents. Bacterium-specific qPCR assays will also be performed. This study focuses on species hypothesised to be associated with increased risk of SPTB, such as BVAB1, Megasphaera, and Sneathia. The final set of species/genera tested will be fine-tuned following analysis of the deep sequencing data from Aim 1, selecting additional bacteria based on a comparison of the relative abundance of individual taxa in women with and without SPTB. A standard exogenous jellyfish qPCR amplification control will be used to assess for PCR inhibitors.49 A broad-range bacterial 16S rRNA gene qPCR assay will be used to measure total bacterial load in each sample.

Histopathological examination of fetal membranes, placenta, and umbilical cord samples

H&E staining of fetal membrane rolls, placental samples, and umbilical cord sections will be graded according to published guidelines by an experienced pathologist (KM).50 Acute and subacute inflammatory lesions will be graded and staged for both maternal and fetal components. Chronic inflammatory lesions will be characterised including any observation of chronic deciduitis or the presence of decidual plasma cells.

Statistical analysis

Sample size estimate and case-cohort population generating

Aim 2 requires the largest sample size and was used to guide sample size estimation for this case cohort study.51 The prospective case-cohort analysis set will include three women who delivered at term for each one with SPTB. Assuming three primary species/genera of interest, Simes’ methodology was used to fix a type-1 error rate adjusted for three tests.52 A sample of 80 SPTB and 240 term births has >80% power to detect a statistically significant ≥2.8 fold difference in the odds of detecting a preconception vaginal bacterial species/genus in women with SPTB versus term delivery, assuming >10% prevalence of the organism at preconception visits for term deliveries.

To accrue 80 SPTB cases including women with spontaneous preterm labour or preterm premature rupture of membranes, a cohort of approximately 1100 women will be enrolled. Once 80 SPTB cases occur, the sample for the case-cohort will be defined. First, cases of spontaneous abortion (<20 weeks gestation) and preterm births without spontaneous labour or preterm premature rupture of membranes will be excluded. Next, a random sample of the remaining pregnancies will be selected such that when added to the remaining SPTB cases, the case-cohort sample will have a term birth to SPTB ratio of 3:1. A sampling fraction f, with f solved using the formula: nf + (1 f)*80=320, where n is the total number of women (cases and non-cases) with delivery data, will be used to select the random sample. Lastly, all of the remaining SPTB cases will be added to the random sample, creating the full case-cohort sample.

Statistical analysis plan

The goal of aim 1 is to characterise and compare preconception vaginal species diversity and richness between women with SPTB vs term birth. All women with SPTB and a random sample of the same number of women with term birth from the case-cohort sample will be included. To describe the overall frequency and relative abundance of species, cumulative rank abundance plots will be generated for each group.53 We will compare the cumulative distribution of preconception vaginal bacterial taxa between women with SPTB versus term birth using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Rarefaction curves will be used to evaluate species richness (number of taxa at a 97% sequence similarity cut-off defining an operational taxonomic unit) in women with SPTB vs term birth. Finally, we will assess species diversity (Shannon Diversity Index54) and species richness (Chao1 richness estimator55) by comparing the mean values between women with SPTB versus term birth. We will perform logistic regression with SPTB status as the outcome and species rank abundance percentage for each species. We will first determine the score statistics (SPTB status as the outcome) for each variable, then rank the variables from largest to smallest score statistic. Next, we will perform the logistic modelling on each of these in rank order of score statistic until reaching a p value of 0.2 in univariate logistic regressions. These data will be examined to refine targets for the primary hypothesis test in aim 2.

For aim 2, based on the literature and informed by aim 1 results, bacterial species/genera will be selected for evaluation using qPCR assays, comparing their presence and concentrations in vaginal specimens sampled before conception. These analyses will use data from the full case-cohort sample and will be weighted to account for the sampling scheme. For each bacterial taxon, we will perform unadjusted logistic regression to examine the association between the presence of that taxon and the risk of SPTB. Multivariable logistic regression analysis will be used to determine the independent contributions of bacterial species to the risk of SPTB. Species associated with SPTB in univariate analyses (p<0.10) will be included in the multivariable model after addressing collinearity. A manual forward stepwise model building approach will be used to address confounding. Potential confounding factors are listed in table 3. For the three species selected for the primary hypothesis test, p<0.033 will be considered statistically significant, using the Simes’ correction for multiple comparisons. Other bacterial taxa may be evaluated as exploratory analyses. Additional exploratory analyses will be performed to investigate the relationship between preconception quantities of specific bacteria and risk of SPTB.

Table 3.

Potential key covariates in analysis of the association between preconception vaginal microbiota and spontaneous preterm birth

| Variable | Timing | Method |

| Demographics | ||

| Maternal age | Baseline | FTFI |

| Educational level | Baseline | FTFI |

| Socioeconomic status | Baseline | FTFI |

| Obstetrical history (eg, no of pregnancies, time since last pregnancy, prior preterm birth) | Baseline | FTFI |

| Prior contraceptive history | Baseline | FTFI |

| Current pregnancy | ||

| Maternal haemoglobin level, blood pressure | Throughout pregnancy | ANC records |

| Fetal health (eg, Apgar scores, spontaneous breathing, birth weight, gender) | Delivery | Delivery records, FTFI or phone interview |

| Maternal infection | Throughout pregnancy | ANC and delivery records, FTFI or phone interview |

| Maternal pregnancy complications | Throughout pregnancy | ANC and delivery records, FTFI or phone interview |

| General health status | ||

| Body mass index | Baseline | Measure weight and height |

| Smoking | Baseline and follow-up | FTFI |

| Alcohol use | Baseline and follow-up | Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) |

| Depressive symptoms | Baseline | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) |

| Periodontitis | Within 4 weeks of baseline | Oral examination |

| Genital tract infection/STI | Baseline | Detection of gonorrhoea, chlamydia and Trichomonas vaginalis by NAAT (Hologic). Wet prep, vaginal and cervical Gram stain. |

| Lactobacilli | Baseline and follow-up | Culture on Rogosa and TMB agar |

| Unprotected sex | Baseline and follow-up | FTFI |

| PSA | Baseline and follow-up | ABACard PSA detection (Abacus Diagnostics) |

| Intravaginal practices | Baseline and follow-up | FTFI |

ANC, antenatal clinic; FTFI, face-to-face interview; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; PSA, prostate specific antigen; STI, sexually transmitted infections; TMB, tetramethylbenzidine.

Aim 3 explores the association between bacteria detected in vaginal preconception samples and fetal membrane samples to further support the role of ascending vaginal bacteria in SPTB. This analysis will also evaluate the association between bacteria identified in the fetal membranes and histological evidence of deciduitis, chorioamnionitis and funisitis. The analysis will use data from women in the case-cohort sample with delivery samples. The exposures are preconception detection of each of the three vaginal species tested for the primary hypothesis in aim 2. Outcomes include detection of the same bacterial species in fetal membranes, deciduitis, chorioamnionitis and funisitis. ORs will be estimated for each exposure using unadjusted logistic regression models, and multivariable logistic regression analyses will be used to adjust for potential confounding factors (table 3).

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public were involved in the design of this research. Healthcare providers providing reproductive/maternal health services and study participants can refer potentially eligible women to the study.

Ethics and dissemination

There are inherent risks to women and fetuses during pregnancy and delivery, but participation in this observational study does not increase these risks. Study participation risks include discomfort associated with the fingerstick for HIV testing, sensitive questions about sexual behaviour, and the pelvic examination; stress associated with HIV or STI diagnosis; and breach of confidentiality. To minimise these risks, experienced Kenyan research staff fluent in both English and Kiswahili conduct a robust consent process. At screening, the screening procedures are explained and written informed consent is obtained with forms available in English and Kiswahili. Eligible women who opt to participate in the study undergo a separate consenting process for study enrolment, including verbal explanation of the procedures and written informed consent. Participants are counselled on potential risks and are informed that they can withdraw from the study at any time. The risk of breach of confidentiality is minimised by following Good Clinical Practice procedures for data security. Signed consents are secured in locked cabinets in a restricted area. Study identification numbers are assigned to deidentify hard copies of the case report forms, which are locked in a restricted area. Data are entered into a password-protected database using encrypted computers. Results will be disseminated to clinicians at study sites and partner institutions, presented at conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Discussion

Most cases of SPTB occur without a known cause.3 BV during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of SPTB, but clinical trials of BV treatment in pregnancy have shown minimal or no reduction in SPTB.9 The MPTB Study addresses the hypothesis that the vaginal microbiota detected during the preconception period may be linked to SPTB. The findings could shift the paradigm for thinking about the mechanisms linking vaginal microbiota and preterm birth, and could be used to guide the development and evaluation of interventions aimed at lowering the risk of SPTB by identifying and eradicating high-risk vaginal bacteria prior to conception.56–58

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the clinic, laboratory and administrative study staff in Nairobi, Mombasa and Seattle for their dedication and teamwork. We are also grateful to Kenyatta National Hospital, Coast Provincial General Hospital and the Mombasa County Department of Health for supporting this research and providing clinical and laboratory space. We thank the study participants whose commitment has made the ongoing implementation of this protocol possible. Development and implementation of the ultrasound quality assurance measures has been generously and skillfully supported by Dr. Robert Nathan (University of Washington) and Dr. Christine Mamai (Kenyatta National Hospital). Lastly, the authors thank Dr. Anne Pulei, Dr. Lydia Okutoyi, Raheli Mukhwana and Grace Wang’ombe (Kenyatta National Hospital), Charity Muthoni and Josephine Mwangi (Coast Provincial General Hospital), and the labor and delivery nurses at KNH and CPGH for their contributions to the successful training, oversight and implementation of delivery sample collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: RSM is the principal investigator. RSM and DNF generated the idea for this study and supervised study protocol development and implementation. GJ-S contributed to essential elements of the protocol related to recruitment and retention of pregnant and postpartum women in Kenya. JK and WJ served as site principal investigators, overseeing study staff and implementation at Kenyatta National Hospital and Ganjoni Health Center. EML, SL, EF, KM, AK and HA participated in designing the study, protocol, data collection tools and staff training. BAR, RSM, DNF and SS developed the statistical analysis plan for the study. DNF, SS and KM oversaw laboratory methods. EML coordinates the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (NICHD R01 HD087346-RSM). RSM received additional support for mentoring (NICHD K24 HD88229). EML was supported by a pre-doctoral fellowship (NIAID T32 AI07140-Lukehart). Data collection and management are made possible using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Washington’s Institute of Translational Health Science supported by grants from NCATS/NIH (UL1 TR002319, KL2 TR002317, and TL1 TR002318).

Competing interests: RSM has received honoraria for consulting from Lupin Pharmaceuticals and receives research funding, paid to the University of Washington, from Hologic Corporation.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Kenyatta National Hospital Ethics and Research Committee #P70/10/2016; University of Washington IRB #STUDY00001472.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Beck S, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. . The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: a systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:31–8. 10.2471/BLT.08.062554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. . Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the sustainable development goals. Lancet 2016;388:3027–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31593-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, et al. . Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008;371:75–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Johnson DC. Maternal infection and adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes. Clin Perinatol 2005;32:523–59. 10.1016/j.clp.2005.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hendler I, Goldenberg RL, Mercer BM, et al. . The preterm prediction study: association between maternal body mass index and spontaneous and indicated preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:882–6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daalderop LA, Wieland BV, Tomsin K, et al. . Periodontal disease and pregnancy outcomes: overview of systematic reviews. JDR Clinical & Translational Research 2018;3:10–27. 10.1177/2380084417731097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hillier S, Marrazzo J, Holmes KK, et al. . Bacterial vaginosis : Holmes KK, Sparling P, Stamm W, et al., Sexually transmitted infections. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Companies, 2007: 737–68. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leitich H, Kiss H. Asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis and intermediate flora as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2007;21:375–90. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brocklehurst P, Gordon A, Heatley E, et al. . Antibiotics for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:CD000262 10.1002/14651858.CD000262.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, et al. . Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108:4680–7. 10.1073/pnas.1002611107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Srinivasan S, Hoffman NG, Morgan MT, et al. . Bacterial communities in women with bacterial vaginosis: high resolution phylogenetic analyses reveal relationships of microbiota to clinical criteria. PLoS One 2012;7:e37818 10.1371/journal.pone.0037818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hyman RW, Fukushima M, Jiang H, et al. . Diversity of the vaginal microbiome correlates with preterm birth. Reprod Sci 2014;21:32–40. 10.1177/1933719113488838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stout MJ, Zhou Y, Wylie KM, et al. . Early pregnancy vaginal microbiome trends and preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:356.e1–356.e18. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Freitas AC, Bocking A, Hill JE, et al. . Increased richness and diversity of the vaginal microbiota and spontaneous preterm birth. Microbiome 2018;6:117 10.1186/s40168-018-0502-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brown RG, Al-Memar M, Marchesi JR, et al. . Establishment of vaginal microbiota composition in early pregnancy and its association with subsequent preterm prelabor rupture of the fetal membranes. Transl Res 2019;207:30–43. 10.1016/j.trsl.2018.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fettweis JM, Serrano MG, Brooks JP, et al. . The vaginal microbiome and preterm birth. Nat Med 2019;25:1012–21. 10.1038/s41591-019-0450-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Romero R, Hassan SS, Gajer P, et al. . The vaginal microbiota of pregnant women who subsequently have spontaneous preterm labor and delivery and those with a normal delivery at term. Microbiome 2014;2:18 10.1186/2049-2618-2-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nelson DB, Shin H, Wu J, et al. . The gestational vaginal microbiome and spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous African American women. Am J Perinatol 2016;33:887–93. 10.1055/s-0036-1581057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Elovitz MA, Gajer P, Riis V, et al. . Cervicovaginal microbiota and local immune response modulate the risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. Nat Commun 2019;10:1305 10.1038/s41467-019-09285-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. DiGiulio DB, Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, et al. . Temporal and spatial variation of the human microbiota during pregnancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:11060–5. 10.1073/pnas.1502875112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Callahan BJ, DiGiulio DB, Goltsman DSA, et al. . Replication and refinement of a vaginal microbial signature of preterm birth in two racially distinct cohorts of US women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:9966–71. 10.1073/pnas.1705899114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stafford GP, Parker JL, Amabebe E, et al. . Spontaneous preterm birth is associated with differential expression of vaginal metabolites by lactobacilli-dominated microflora. Front Physiol 2017;8:615 10.3389/fphys.2017.00615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nelson DB, Hanlon A, Nachamkin I, et al. . Early pregnancy changes in bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria and preterm delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2014;28:88–96. 10.1111/ppe.12106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Menard JP, Mazouni C, Salem-Cherif I, et al. . High vaginal concentrations of Atopobium vaginae and Gardnerella vaginalis in women undergoing preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:134–40. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c391d7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nelson DB, Hanlon A, Hassan S, et al. . Preterm labor and bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria among urban women. J Perinat Med 2009;37:130–4. 10.1515/JPM.2009.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rahkonen L, Rutanen E-M, Unkila-Kallio L, et al. . Factors affecting matrix metalloproteinase-8 levels in the vaginal and cervical fluids in the first and second trimester of pregnancy. Hum Reprod 2009;24:2693–702. 10.1093/humrep/dep284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Andrade Ramos B, Kanninen TT, Sisti G, et al. . Microorganisms in the female genital tract during pregnancy: tolerance versus pathogenesis. Am J Reprod Immunol 2015;73:383–9. 10.1111/aji.12326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prince AL, Antony KM, Chu DM, et al. . The microbiome, parturition, and timing of birth: more questions than answers. J Reprod Immunol 2014;104-105:12–19. 10.1016/j.jri.2014.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National AIDS & STD Control Programme Guidelines on use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV in Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gajer P, Brotman RM, Bai G, et al. . Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:132ra52 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Srinivasan S, Liu C, Mitchell CM, et al. . Temporal variability of human vaginal bacteria and relationship with bacterial vaginosis. PLoS One 2010;5:e10197 10.1371/journal.pone.0010197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. National AIDS & STI Control Programme of Kenya Kenya national guidelines for prevention, management and. Nairobi, Kenya: Control of Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lynch CD, Jackson LW, Buck Louis GM. Estimation of the day-specific probabilities of conception: current state of the knowledge and the relevance for epidemiological research. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2006;20:3–12. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00765.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Laine MA. Effect of pregnancy on periodontal and dental health. Acta Odontol Scand 2002;60:257–64. 10.1080/00016350260248210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Health Organization Oral health surveys - basic methods. 5th edn Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol 2007;78:1387–99. 10.1902/jop.2007.060264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pardthaisong T, Gray R, Mcdaniel E. Return of fertility after discontinuation of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and intra-uterine devices in northern Thailand. Lancet 1980;315:509–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(80)92765-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schwallie PC, Assenzo JR. The effect of depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate on pituitary and ovarian function, and the return of fertility following its discontinuation: a review. Contraception 1974;10:181–202. 10.1016/0010-7824(74)90073-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists Committee opinion no 611: method for estimating due date. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:863–6. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000454932.15177.be [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Odeny TA, Newman M, Bukusi EA, et al. . Developing content for a mHealth intervention to promote postpartum retention in prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programs and early infant diagnosis of HIV: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2014;9:e106383 10.1371/journal.pone.0106383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lannon SMR, Adams Waldorf KM, Fiedler T, et al. . Parallel detection of Lactobacillus and bacterial vaginosis-associated bacterial DNA in the chorioamnion and vagina of pregnant women at term. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2019;32:2702–10. 10.1080/14767058.2018.1446208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol 1991;29:297–301. 10.1128/JCM.29.2.297-301.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Martin HL, Richardson BA, Nyange PM, et al. . Vaginal lactobacilli, microbial flora, and risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexually transmitted disease acquisition. J Infect Dis 1999;180:1863–8. 10.1086/315127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Eschenbach DA, Davick PR, Williams BL, et al. . Prevalence of hydrogen peroxide-producing Lactobacillus species in normal women and women with bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol 1989;27:251–6. 10.1128/JCM.27.2.251-256.1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hobbs MM, Steiner MJ, Rich KD, et al. . Good performance of rapid prostate-specific antigen test for detection of semen exposure in women: implications for qualitative research. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:501–6. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a2b4bf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Golob JL, Pergam SA, Srinivasan S, et al. . Stool microbiota at neutrophil recovery is predictive for severe acute graft vs host disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:1984–91. 10.1093/cid/cix699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, et al. . DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods 2016;13:581–3. 10.1038/nmeth.3869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Matsen FA, Kodner RB, Armbrust EV. pplacer: linear time maximum-likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic placement of sequences onto a fixed reference tree. BMC Bioinformatics 2010;11:538 10.1186/1471-2105-11-538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Khot PD, Ko DL, Hackman RC, et al. . Development and optimization of quantitative PCR for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis with bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. BMC Infect Dis 2008;8:73 10.1186/1471-2334-8-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kraus F, Redline R, Gersell D, et al. . Atlas of nontumor pathology - placental pathology. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kim MY, Xue X, Du Y. Approaches for calculating power for case-cohort studies. Biometrics 2006;62:929–33. 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2006.00639_1.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Simes RJ. An improved Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika 1986;73:751–4. 10.1093/biomet/73.3.751 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hughes JB, Hellmann JJ, Ricketts TH, et al. . Counting the Uncountable: statistical approaches to estimating microbial diversity. Appl Environ Microbiol 2001;67:4399–406. 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4399-4406.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Krebs C. Ecological methodology. New York: Harper Collins, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chao A. Non-Parametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scand J Stat 1984;11:265–70. [Google Scholar]

- 56. McClelland RS, Balkus JE, Lee J, et al. . Randomized trial of periodic presumptive treatment with high-dose intravaginal metronidazole and miconazole to prevent vaginal infections in HIV-negative women. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:1875–82. 10.1093/infdis/jiu818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. McClelland RS, Richardson BA, Hassan WM, et al. . Improvement of vaginal health for Kenyan women at risk for acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: results of a randomized trial. J Infect Dis 2008;197:1361–8. 10.1086/587490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. . Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:1283–9. 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wanyonyi SZ, Napolitano R, Ohuma EO, et al. . Image-scoring system for crown-rump length measurement. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014;44:649–54. 10.1002/uog.13376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.