Abstract

Objectives

Physical activity is widely recommended in the treatment and management of cystic fibrosis (CF). Despite the numerous physical and psychological benefits, many young people with CF are not achieving the recommended levels of physical activity. The aim of this systematic review was to identify and synthesise available qualitative investigations exploring the motives for, barriers to and facilitators of physical activity among young people with CF.

Methods

The following six electronic databases were systematically searched: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), CINAH, EMBASE, MEDLINE, MEDLINE-in-process, PsycINFO up to August 2019. Keywords were used to identify qualitative research that explored engagement in physical activity among young people with CF. Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers, and potentially relevant articles were retrieved in full. Articles were eligible for inclusion if they employed any qualitative method and recruited participants under the age of 24 years with CF. Risk of bias of included studies was assessed via the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Results were synthesised using a thematic approach.

Results

Seven studies met our inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Overall, studies were of moderate to high quality. Thematic synthesis identified nine main themes that encompass motives for, barriers to and facilitators of physical activity among young people with CF. These were (1) Perceptions of physical activity. (2) Value attributed to physical activity. (3) Social influences. (4) Competing priorities. (5) Fluctuating health. (6) Normality. (7) Control beliefs. (8) Coping strategies. (9) Availability of facilities. Previous reviews have been unable to identify intervention characteristics that influence physical activity behaviour.

Conclusions

This review provides detailed information on the physical (biological—clinical), psychological, social and environmental influences on physical activity behaviour, thus providing numerous targets for future interventions. This in turn could facilitate promotion of physical activity among young people with CF.

Keywords: qualitative research, respiratory medicine (see thoracic medicine), sports medicine, cystic fibrosis, paediatric thoracic medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first synthesis of qualitative work that has explored barriers and facilitators to physical activity among young people with CF.

Risk of bias was assessed independently by two authors using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool for qualitative and observational studies.

We were only able to include studies that were published in full in English, therefore we may have missed potentially relevant data.

Three of the studies included in the review were authored by one research team; this may reflect a smaller distribution of participants, potentially reducing the transferability of findings.

Background

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a progressive, genetic condition affecting more than 10 400 people in the UK, and more than 70 000 worldwide.1 Mutations in the CF transmembrane affect the regulation of salt and water movement across cell membranes, resulting in abnormally thick mucus in the lungs and digestive system.1 This leads to bronchiectasis, inflammation, recurrent infections and eventually respiratory failure.1 There is no cure for CF, but advances in treatment mean that people with CF have a greater life expectancy than previous generations.2 However, treatment is demanding, comprising a complex regime of pharmacological treatments, physiotherapy and airway clearance, high calorie diets and physical activity.3

Physical activity, inclusive of sport, exercise and recreational activities, are widely recommended in the management of CF4 due to the beneficial impact on aerobic capacity and lung function,5 6 as well as improvements in cardiovascular endurance,7 muscular strength8 and mucus clearance.9 Physical activity also has a positive impact on health-related quality of life,6 fatigue10 and psychological well-being.11 The role of physical activity in the management of CF is viewed favourably by both healthcare professionals12 13 and people with CF.14 15 Despite this, like their healthy peers, many children with CF are failing to achieve the national recommended 60 min of daily moderate to vigorous activity,16 17 with levels reducing further throughout adolescence.18 This has implications for physical health,19 and a detrimental impact on psychological health,6 and reduces opportunities for social interaction.6

The impact of physical activity on the physical and psychological health of individuals with CF has been well established. However, in contrast to the literature regarding the benefits of physical activity, there is a paucity of literature regarding how best to support young people with CF to be more physically active. One quantitative review, of interventions for promoting physical activity among individuals with CF,20 found little evidence to support the effectiveness of any approach to promote physical activity. However, in order to successfully change behaviour, it is necessary to identify and target determinants of the behaviour in question.21 However, the quantitative review did not consider the modifiable determinants of physical activity and is therefore not able to explain what these approaches were targeting (ie, mechanisms of action) and why they may have failed to promote physical activity.

A large body of literature has explored determents, barriers and facilitators to physical activity among young people without chronic conditions.22 Individual-level (eg, enjoyment, motivation), interpersonal (social relationships) and environmental factors (eg, access to green space) have been highlighted as important determinants of physical activity.22–24 However, young people with CF have a unique set of circumstances, for example, fluctuating health, which is likely to influence participation in physical activity. It is therefore necessary to explore barriers and facilitators to physical activity among this population. There is widespread agreement among intervention developers that eliciting and addressing the needs and perspectives of the target audience is a critical part of intervention development.25 It is impossible for research teams to predict the needs and preferences of the target audience, and so it is crucial that we elicit the views of intervention recipients.26 This will facilitate the identification of potentially modifiable psychological, social, environmental and behavioural determinants of physical activity for young people with CF and will inform the selection of approaches to effectively support changes in physical activity for this population.27 As qualitative methods provide in-depth, rich and detailed information about a topic as experienced by target populations they are well placed to explore this topic. While research relating to motives, barriers and facilitators of physical activity among young people with CF has been conducted,28–30 as yet, no review has comprehensively and systematically synthesised this literature.

The socioecological model provides the overarching framework for this review.31 The model highlights the multiple layers of influence on the health of the population. The model recognises that, in addition to personal lifestyle, the physical and social environment, and wider socioeconomic conditions affect population health. As interventions may operate at any of these levels, the current work aims to explore the barriers and facilitators to physical activity that operate at these multiple levels. Using this model, we explore barriers and facilitators to physical activity among young people with CF.

Aims

This systematic review aimed to identify and synthesise the qualitative literature on the motives for, barriers to, and facilitators of physical activity among young people with CF. Specifically, we were interested in understanding: (1) What motivates young people with CF to be active. (2) What are the barriers to being physically active among young people with CF. (3) What facilitates physical active among young people with CF.

Methods

The review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses statement (online supplementary 1).32

bmjopen-2019-035261supp001.pdf (28.9KB, pdf)

Search strategy

The following six electronic databases were searched: ASSIA, CINAH, EMBASE, MEDLINE, MEDLINE-in-process, PsycINFO up to August 2019. Keyword search terms included: Cystic Fibrosis; Physical activity; Exercise; Sport; Recreation (see full search strategy in online supplementary 2). Search terms were adapted for each database. Reference lists of existing reviews were also searched. To identify any unpublished or ongoing work, key authors and experts in the field were contacted.

bmjopen-2019-035261supp002.pdf (32.2KB, pdf)

Study selection

All titles and abstracts of identified records were reviewed by the lead author. A second reviewer independently reviewed 10% of records. As there was 100% agreement between the two reviewers, it was decided that it was not necessary for all records to be reviewed by a second reviewer. Potentially relevant articles were retrieved in full and all (100%) were assessed independently by both reviewers against the inclusion criteria and quality assessment (as below).

Inclusion criteria

Types of studies to be included

Any study using qualitative methods to identify motivators, barriers or facilitators to physical activity among young people with CF was included. We did not limit the search by date or location, but inclusion was limited to studies written in English.

Participants/population

Our population of interest was children and young people with CF under the age of 24 years. Studies including adults were also eligible for inclusion if the majority of participants fell between the relevant age bracket.

Studies including participants with multiple conditions (eg, those studying people with chronic disease) were included as long as data provided by individuals with CF were clearly indicated.

Intervention/exposure

Any study describing motives for or barriers or facilitators to physical activity among young people with CF.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies that: (1) Did not include individuals with CF. (2) Promote physical activity or exercise without consideration of barriers or facilitators. (3) Are not reported in enough detail to identify barriers or facilitators to physical activity. (4) Do not primarily target young people (under the age of 24 years). (5) Are not published in English. (6) Do not use qualitative methods.

Primary outcome

Motives for physical activity participation among young people with CF.

Barriers to physical activity participation among young people with CF.

Facilitators of physical activity participation among young people with CF.

Data extraction

Data were extracted independently by the first and second author using a data extraction template developed for this purpose. Any disagreements were resolved via discussion.

Data were extracted on:

Author and year and location of publication

Study design

Sample size and characteristics

Data collection methods

Method of analysis

Barriers and facilitators identified or targeted

Overall conclusions

Risk of bias

Risk of bias was assessed independently by the first and second authors using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool for qualitative and observational studies.33 Κ statistics indicated excellent levels of agreement (>0.8). Any disagreements were resolved via discussion. The CASP is a 10-item checklist comprising questions relating to the research design, data collection and analysis, reflexivity, ethics, implications of the research. We adopted a 3-point rating system as used by a number of authors,34 35 in which a rating point from 1 to 3 is given to each article for each of the CASP’s questions. Studies receive a score of 1 for issues that are not mentioned or poorly justified; a score of 2 for little elaboration of an issue; and a score of 3 for issues that are well justified. This results in a quality score of between 8 and 24. Those scoring less than 15 were categorised as weak. Those scoring between 16 and 23 were considered moderate, and those scoring 24 points were considered strong. In this review, the CASP was used to describe the quality of the studies for contextual purposes. No exclusions were made on the basis of CASP Scores.

Strategy for data synthesis

Data from qualitative studies were synthesised using a thematic method36 in which common themes from each study are highlighted and discussed. First, the results and discussion sections of the manuscripts were read by two reviewers, and relevant data were extracted and entered into Nvivo for analysis. Thematic analysis followed three stages as recommended by Thomas and Harden.37 Focusing on authors’ interpretations of the data, the first stage involved the creation of initial codes to describe or summarise relevant text. In the second and third stages, codes were organised into descriptive themes, and finally into analytical themes (stage 3). We employed multiple measures to maximise trustworthiness within this study. This included clear exposure of methods of data collection and analysis, maintaining an audit trail of the analysis process, attention to negative cases, and engaging in multiple discussions with the research team to challenge themes as they develop.

Patient and public involvement

A patient and public involvement group was established to inform the development and direction of our research. The group met regularly (via Skype) and consisted of young people with CF, physiotherapists, technicians and paediatricians. In the first instance, the group were asked to suggest research topics and questions they would like to be answered. Later, the group met to support the development of the protocol. Finally, the group were very much involved in disseminating the results of the review though the development and production of short animations.

Results

Study selection

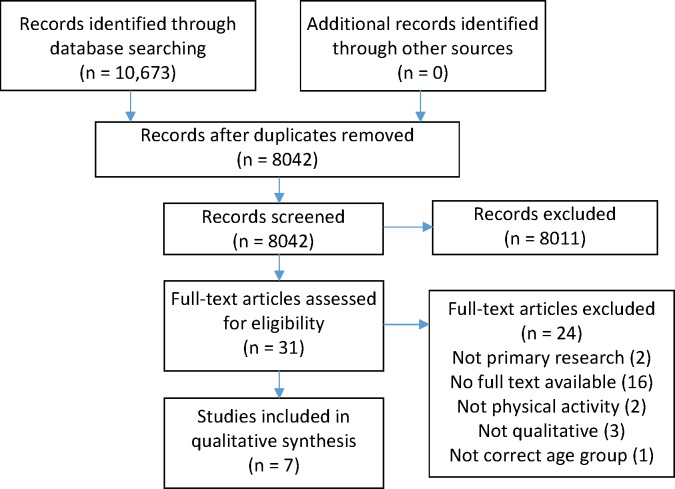

The search results (figure 1) identified 10 673 records, of which 2631 were duplicates. After application of the exclusion criteria, seven studies were included in the thematic analysis.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Overview of studies

The included studies were published between 2008 and 2018. One study was conducted in Australia,38 three in Canada,39–41 two in USA,42 43 and one in the UK.44 All studies reported the use of semistructured interviews. One study used a multifaceted approach to data collection; also using focus groups, mapping, photoelicitation and traffic light posters.38 One study reported the use of telephone interviews.43 Methods of analysis included interpretive phenomenology,38 44 thematic analysis,40 42 43 grounded theory41 and case study analysis.39 The rationale for the conduct of the work was to increase understanding of physical activity among children with CF,38 promote children’s participation in research38 and to inform the development of interventions to promote physical activity.40–43

Participants were between the ages of 4 years and 18 years; although only one study included participants that were under the age of 8 years.38 All had a confirmed diagnosis of CF, although two studies included participants with other chronic conditions; including coronary heart disease,40 asthma38 and type 1 diabetes.38 Three studies also included parents of young people with CF alongside the perspective of the young person with CF,38 40 42 and one study included the views of healthcare professionals.44 Three of the included studies were written by the same lead author.40 41 See table 1 for an overview of included studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Reference | Location | Participants | Data collection | Data analysis | Summary of findings |

| Fereday et al 38 | Australia | Twenty-five participants (aged 4–16 years). Fourteen had a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, six asthma and five cystic fibrosis. |

A combination of focus groups, interviews, drawing maps, taking photos, and traffic light posters | Interpretive phenomenological analysis | Children and young people described their active participation in a wide variety of physical activities including organised sports and play but made very little mention of any negative influence or impact due to their disease. Their parents' stories described the diligent background planning and management undertaken to enable their child to participate in a wide range of physical activities. |

| Happ et al 42 | USA | Eleven child-parent pairs. Five girls, six boys (aged 10–16 years). All had a diagnosis of CF. Six children were from the experimental group, and five from the attention-control group. Parent interview participants were nine mothers and four fathers, aged 29–51 years. All participants were Caucasian. |

Individual child and parent interviews, conducted at 2 months into the exercise programme and again at 6 months | Thematic analysis | Five major thematic categories describing child and parent perceptions and experience of the bicycle exercise programme were identified in the transcripts: (A) Motivators. (B) Barriers. (C) Effort/work. (D) Exercise routine. (E) Sustaining exercise. Research participation, parent-family participation, health benefits, and the child’s personality traits were primary motivators. Competing activities, priorities and responsibilities were the major barriers to implementing the exercise programme as prescribed. Motivation waned and the novelty wore off for several (approximately half) parent-child dyads, who planned to decrease or stop the exercise programme after the study ended. |

| Moola 39 | Canada | Two children. One male, one female. Participants were randomly selected from an ongoing trial. |

Semistructured interviews and field notes | Case study analysis | The findings beg researchers to consider: (A) How children with life-limiting diseases borrow multiple illness narrative types. (B) The role of development in influencing the kinds of stories that children can tell. (C) The impact of illness narratives on physical activity. By rendering the tales of two youths with CF in this study, we respond to Aurthur Frank’s call; taking a multiple narrative turn, we listen to stories of a different kind of suffering. |

| Moola 41 | Canada | Fourteen participants. Ten male, five female (aged 11–17 years). All had a diagnosis of CF. Although the majority of the sample was Caucasian, one participant self-identified as Black and the other as East Indian. |

Semistructured interviews | Grounded theory | The participants demonstrated positive or negative perceptions towards physical activity and different experiences—such as parental support and illness narratives—influenced youths’ perceptions. In addition, the participants experienced physical activity within the context of reduced time. Recommendations for developing physical activity interventions, including the particular need to ensure that such interventions are not perceived as wasteful of time, are provided. |

| Moola et al 40 | Canada | Twenty-nine parents who provided care to a child with CF or CHD between the ages of 10 years and 18 years, participated (16 parents from the CF clinic and 13 parents from the CHD centre). Parents were from a range of urban and rural locations across Ontario and Quebec and access to physical activity opportunities varied. |

Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis | Parents discussed the numerous benefits and barriers associated with physical activity for both child and self. Role modelling was a critical social process to overcoming barriers. Parents’ experiences were situated within the broader family context characterised by a prevailing sense of stress and complexity. |

| Shelley et al 44 2018 | UK | Nine participants, five female, four male (aged 8–16 years). All participants had a confirmed diagnosis of CF. | Semistructured interviews | Interpretive phenomenological analysis | Findings suggest that experiences of PA in children and young people with CF are largely comparable to their non-CF peers, with individuals engaging in a variety of activities. CF was not perceived as a barrier per se, although participants acknowledged that they could be limited by their symptoms. Maintenance of health emerged as a key facilitator. In some cases PA offered patients the opportunity to ‘normalise’ their condition. Participants reported enjoying wearing the monitoring devices and had good compliance. Wrist-worn devices and devices providing feedback were preferred. HCPs recognised the potential benefits of the devices in clinical practice. Recommendations based on these findings are that interventions to promote PA in children and young people with CF should be individualised and involve families to promote PA as part of an active lifestyle. Patients should receive support alongside the PA data obtained from monitoring devices. |

| Swisher 43 | USA | Ten participants (aged 13–17 years). All participants had a diagnosis of CF. | Semistructured telephone interviews | Verbatim and transcripts were coded using the line-by-line coding process, thus allowing the researcher to deconstruct the data into discrete pieces of information that could be compared and grouped into categories. In order for a code to be assigned to a response, the code had to be identified by both principal investigators and the graduate student. | All participants articulated understanding the importance of participating in physical activity for health benefits. Factors that served as facilitators to participation in physical activity included improving general or lung-specific health, as well as mental health. Barriers included general discomfort, increased lung symptoms and disinterest. |

CF, cystic fibrosis; CHD, Congenital heart disease; HCP, Health care professional; PA, Physical activity.

Risk of bias

An overview of the quality of the included studies is presented in table 2. All seven studies were considered to be of moderate quality.

Table 2.

Quality assessment

| Article | Clear aim | Appropriate methodology | Appropriate research design | Appropriate recruitment strategy | Data collection addressed the research issues | Adequate consideration of reflexivity | Ethical issues | Sufficient rigour of data analysis | Clear statements of findings | Valuable research | Total |

| Fereday et al 38 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 21 |

| Happ et al 42 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 21 |

| Moola 39 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 23 |

| Moola 41 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 22 |

| Moola et al 40 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 23 |

| Shelley et al 44 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 21 |

| Swisher43 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 22 |

Thematic synthesis

Thematic synthesis identified nine main themes that encompass motives for physical activity, barriers to and facilitators of physical activity at the level of the individual, the social environment, and the built and natural environment as outlined in the socioecological model. These main themes were: (1) Perceptions of physical activity. (2) Value for physical activity. (3) Social influences. (4) Competing priorities. (5) Fluctuating health. (6) Normality. (7) Control beliefs. (8) Coping strategies. (9) Availability of facilities. The data provided below are quotes from the participants who had taken part in the primary studies and were reported by the authors of the included studies to illustrate their findings.

Perceptions of physical activity

Within the seven papers, positive and negative perceptions of physical activity were considered to be influential in engagement with physical activity.39 42–44 Positive perceptions included enjoyment, mastery and autonomy, and appeared to be highly influenced by previous experiences of physical activity, the health of the individual and the social environment in which physical activity was performed. A sense of ‘fun’ and ‘enjoyment’ appeared to be important for sustained physical activity;41 43 as evidenced by one participant in the study by Swisher et al who states; “I want to exercise because I like doing the activities… they are fun… I feel good after” (p110). Likewise, perceptions of ‘energy’ versus ‘work’ were influential; with individuals who report feeling ‘energetic’ and ‘empowered’ after activity more likely to report continued physical activity.43

Participants who had positive perceptions of physical activity also often reported mastery experiences; mentioning the building of a sense of competence and achievement.41 One participant in the study by Moola et al 41 describes how her preferred activity (dance) ‘is really exciting. There is a lot of anticipation leading up to it. I like working hard to achieve things’ (P52). In contrast, negative perceptions of physical activity appeared to decrease motivation for physical activity. Unpleasant sensations such as discomfort, muscle soreness, fatigue, joint pain and breathlessness,42 44 and a lack of enjoyment or boredom43 were reported. As an example, one participant in the study by Shelley et al 44 dislikes the way exercise ‘gives you the pains the next day. Like you’re dragging your legs up the stairs the next day’ (P340). Feelings of self-consciousness resulted in young people feeling exposed and vulnerable,39 despondent,40 and anxious to avoid physical activity.40 Negative perceptions of physical activity appeared to be exacerbated by CF and symptoms of CF (eg, tiredness, breathlessness);41 44 as highlighted by a quote from a participant in the study by Moola et al:41 “I know enough times from being sick and trying to run on the treadmill… so then I say, ‘if I am going to be tired, then why do it?’” (P54).

Value attributed to physical activity

Included studies presented individuals as placing high value or low value on physical activity. Physical activity was considered to be important for improving general health for both young people with CF42 43 and their families.40 It was also viewed as critical for the management of CF; both in terms of preventing or delaying deterioration and in managing symptoms.40 42–44 As an example, one participant in Swisher’s43 study described how physical activity ‘helps my lungs and stuff…It helps me breathe better…it keeps me active so I could always run around’ (P110). However, this only appeared to be the case for those who enjoyed physical activity; and found they felt better after activity. For those who did not enjoy PA, the unpleasantness associated with physical activity appeared to outweigh any positive associations.

The role of physical activity in psychological health was not mentioned as frequently as its contribution to physical health; only being noted as important in one study.43 Despite being aware of the benefits of physical activity, some young people with CF placed no value on physical activity—particularly if it was perceived to be unpleasant.41 Indeed, health improvement and CF management were not sufficiently motivational for those who were not active; with one participant in the study by Moola et al 41 acknowledging that: ‘(physical activity) should be higher on the priority list…. But because I know that it is hard, I do not want to make myself work hard’ (P54).

Social influences

All studies included in the review highlighted the role of the parents/care providers in influencing physical activity behaviour. Parents were described as knowledgeable about the role played by physical activity in the health of their child,38 41 and appeared to play a key role in acting as strong physical activity role models.40–42 This included providing children with the skills they need to be active,42 providing tangible support,38 44 planning, structuring activities and overcoming barriers,38 41 42 providing opportunities for physical activity, and providing encouragement and motivation.41 42 44 For example, one parent in Fereday’s study38 describing a willingness to drive her daughter to a dance class (an hour round trip) five nights a week because ‘we are relieved she loves dancing so much because it is something she can do all year round, it's indoors, dry and warm’ (P6).

Parental support could be detrimental to physical activity behaviour if parents were sedentary40–42 or overbearing.44 This is demonstrated by a quote from a participant in Shelley’s study44 in which the participant states “I did a mile on the treadmill the other day, and Dad was like, ‘No, you’re going to do another one… (I feel like) I’m going to slap him. Push him off his bike. You do another mile’” (P340). Parents themselves were aware of the impact of their physical activity on their child’s physical activity behaviour; although often struggled to motivate themselves and their child to be active, with one parent participant in Happ’s study42 reporting that ‘It is hard for me to make him exercise just because I don’t, I guess’ (P309).

The role of social comparison was strongly noted by three of the seven studies.40 43 44 Interestingly, social comparison could be motivational; with young people reporting increased efforts to ensure that they were able to ‘keep up’ with their peers.44 For example, one participant in Shelley’s study44 describes how ‘When I can do what my mates are doing I just feel better, because I know that it doesn’t show that it’s affecting me, and I can keep up with my mates and just do all the exercise’ (P340). In contrast, not being able to keep up with peers40 and/or needing to take regular breaks40 could lead to embarrassment,43 anger and frustration;44 making adolescents ‘stand out’—something they appear motivated to avoid.43 This was exacerbated by negative comments or treatment by others, including teachers and coaches.38 40 Indeed, one participant in Moola’s study41 describes feeling that CF precludes him from sport:

I feel small, I feel skinny. I do not feel like I fit in with other kids… and they think that I am bad and that I have some disease … they talk rudely about me to themselves … if it (sports programme) is for kids that are not sick—there is no point in going. It is all healthy kids, and they are active, and it is a place for them (P55).

Four of the seven studies reported a beneficial effect of positive friendship groups on physical activity behaviour,38 40 41 44; either through providing support,38 39 or making activity more enjoyable.41 44 One study reported how participation in physical activity could even extend the young persons’ social group,38 with participants describing how they had made friends through various activities. Shelley et al 44 present a quote from a young person with CF who uses humour when her CF prevents her from being as active as her friends:

Like one of us wins a race or wins a game or something, I can go, ‘Oh yes, well, I’ve got CF’, and then it’s like pulling a CF card…I just find it funny, because they’re like, ‘aaaaaah! She’s done it again’…we have a laugh about it… (P370).

Competing priorities

Of the seven included studies, a lack of time for physical activity due to competing priorities was mentioned in three.40–42 Busy schedules were reported as a barrier, particularly when taking into account an already burdensome treatment regime.42 Participants in the study by Moola et al 41 described how physiotherapy ‘robbed them of time’ that would otherwise have been used for physical activity; ‘I know that I need to do physical activity, but it is just sometimes hard when things interfere, like medicine or Positive Expiratory Pressure (PEP)’ (P556).

For others, limited time prohibited physical activity because they would rather spend the time doing something meaningful and enjoyable for them (such as seeing friends).41 As a lack of time due to treatment, one study described how participants alluded to a lack of time in a symbolic sense.41 Within this study, participants presented concerns that ‘time was running out’ due to a shortened life span. This increased the pressure to achieve significant milestones (eg, attaining a career, getting married, etc) within a shortened life span.41

Fluctuating health

Ill-health could prevent physical activity either through illness exacerbations or exacerbations of symptoms.38 39 41 43 44 Indeed, serious or disruptive events such as hospitalisation and infections could deter even the most motivated of people38 39 with a participant in the study by Moola et al 41 describing how draining physical activity can be when sick: ‘when I am really sick, I even find brushing my teeth difficult’ (P54).

Symptoms, such as breathlessness, fatigue and coughing exacerbated the perceived unpleasantness associated with physical activity, leading to avoidance of activity whenever possible.40 43 44 In contrast, relative ‘wellness’ appeared to inspire some to be more active,39 with one participant from the study by Shelley et al 44 describing that he is active because: “I am generally quite well, I can do it… I tend to have quite a high lung function, and I don’t really get ill a lot…” (P340). Depression, although not a strong theme, was an issue raised in two studies39 41 as potentially having a detrimental impact on physical activity. In particular, Moola and Faulkner39 present a quote from a participant describing how her decline in activity signifies a decline in her health:

I also know that I am not going to live as long as everybody else so that is hard. I feel like it is out of my control, I feel helpless, how I used to be able to do it (physical activity), and now I can’t. It is kind of depressing. It makes me think that it is a progressive disease, and it make me think that it is getting worse … it makes me worried (P55).

Normality

The concept of normality was highlighted in three of the seven studies.40 41 44 Normality appeared to be both a motive for physical activity,39 as well as a barrier to physical activity.39 40 For some, physical activity was used to provide an opportunity for the young people to feel normal. It provided a window within which they considered themselves to be ‘just like everyone else’.44 Physical activity appeared to minimise differences between themselves and those without CF. For example, Shelley et al 44 present a quote from one participant who states: “It’s like you’re just doing it because you can, and you want to. You kind of feel the same as everyone else for an hour and a half” (P6).

Interestingly, while some were of the opinion that physical activity was something that everyone, with or without chronic conditions, should be doing to improve their health,44 others felt that having CF meant that they had to take part in physical activity while their friends (without CF) did not.39 Participants who felt they were in some way not normal were also more likely to report feeling self-conscious.39 40 Indeed, physical activity appeared to accentuate the extent to which some young people felt thin, or body conscious, or ‘not good at sport’ compared with their peers.39 40 One parent participant in the study by Moola et al 40 describes how her son: “wonders if he is different… He avoids team sports where you need a big size… but he does care” (P606).

Control beliefs

Individual differences in perceptions relating their ability to control or manage their condition appeared to influence participants’ use of active or passive coping strategies. While CF is a chronic condition that cannot be cured, individuals varied in the extent to which they viewed CF as something that could be controlled and managed. Those who adopted a fatalistic approach, that is, were of the opinion that there was nothing that they could do to cure CF, were less motivated to adopt positive self-care behaviours such as physical activity.39 41 For example, one participant in the study by Moola and Faulkner39 describes how her inability to cure her CF makes her unwilling to adopt certain self-care behaviours:

“If there was something that would get rid of CF, I would do it all the time (laughing)! It is not like that…. It’s like ‘I have to do this for the rest of my life? Screw it! Who cares! I am not going to do it anymore” (P36).

In contrast, a second group of participants was of the opinion that they were in control of their CF, and reported that having CF did not need to stop them or prevent them from doing anything,38 41 44 provided they put their minds to it. In particular, one participant in Shelley’s study44 states that: “I know just because I’ve got CF doesn’t mean I can’t do it” (P340).

Coping strategies

Strategies for overcoming barriers to physical activity included both functional and dysfunctional coping strategies. Studies discussed how participants had integrated strategies for dealing with symptoms, such as slowing down or resting when necessary.38 To deal with structural barriers, people with CF38 40 and their parents38 had a variety of strategies, often involving elaborate planning.38 For those who were self-conscious of symptoms reported tactics such as avoiding physical activity in public places.40 One participant in the study by Fereday et al 38 describes a strategy of reducing the intensity of the activity or resting whenever necessary: “He coped and he kept wanting to play but he really needed a break. After resting a couple of minutes he is as good as gold” (P8).

Others had strategies for dealing with difficult emotions,40 such as fear and anxiety.41 In particular, Moola et al 41 present a quote from a participant describing how positive self-talk prevents them from giving up: “When it is talked about it is a different issue… I tell myself ‘that’s not true. You can do it – it is going to be harder, but you can still do it’” (P32).

However, for some, avoidance of physical activity was the preferred method of coping with any embarrassment.40 Indeed, one participant in the study by Moola and Faulkner40 describes how the embarrassment prevents her from taking part in certain activities: “You can see my ribs and I do not want to wear a two piece bathing suit or go swimming” (P605).

Facilities and opportunities

Finally, availability of facilities was considered to have an impact on physical activity behaviour.42 44 Good access to local community facilities (eg, swimming pools, sports centres) and private clubs was reported to increase physical activity among young people with CF.44 Having the opportunity to walk to school was also considered to promote autonomy for physical activity.44 In contrast, lack of access to ‘different’ facilities, or opportunities to try new and exciting activities were mentioned as barriers to physical activity.44 The emphasis here appeared to be not on the availability per se, but on the availability of facilities that were not considered to be boring; for example, one participant in the study by Shelley et al 44 described a limited range of facilities for different sports: “A few more different clubs that do different sports that are around, because there isn’t many” (P340). However, facilities and opportunities for physical activity appeared to be influenced by seasonal variation; with more young people reportedly being more active in the summer months.42

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to examine and synthesise the qualitative literature on the barriers of and facilitators to physical activity among young people with CF. In contrast to previous reviews, the current review used systematic methods to identify and retrieve all relevant research. In accordance with the socioecological model, our analysis highlights multiple and interacting influences on physical activity behaviour at the level of the individual, and the social and physical environment in which physical activity occurs. The value and importance placed on physical activity by the young people, as well as well as perceptions of normality, control and coping strategies used by young people all appeared to be influenced by the social and physical environment in which they lived and performed the activity.

As well as barriers and facilitators to physical activity that are specific to young people with chronic conditions, we also identified barriers and facilitators that are often cited in the literature in relation to young people without chronic conditions. In accordance with previous research23 24 highly valuing and/or enjoying physical activity, and having an active family or social group were identified as having a key role in facilitating physical activity. Likewise, a low value for physical activity, lack of enjoyment of physical activity, and sedentary or overbearing families have all been shown to negatively influence participation in physical activity. However, within this review, we were also able to identify key barriers and facilitators that are specific to young people with CF. Having relatively stable health—or the perception that CF does not need to prevent physical activity, and using physical activity as a vehicle to normality, appeared to facilitate engagement with physical activity. In contrast, fluctuating health status increased the potential for negative perceptions of physical activity and low perception of control over CF, and use of passive coping strategies appeared to hinder engagement in physical activity. While the presence of competing priorities is not limited to those with CF, this theme appeared to be particularly significant for this population, largely due to a very time-consuming treatment regime combined with time pressures faced by those with a reduced life expectancy. Systematic reviews have shown that beliefs relating to the extent to which conditions (and associated symptoms) can be cured or controlled, influence behaviour among multiple populations,45 including individuals with CF.46 47 The current review provides evidence to show that such beliefs are also influential in physical activity CF behaviour. CF cannot be cured, and this at times led to reports of despondency and feelings of hopelessness. In these circumstances, engagement in physical activity was viewed as ‘pointless’ given that it could not cure the condition. Beliefs relating to the controllability of symptoms during physical activity could also lead to avoidance of physical activity. In contrast, individuals who felt in control of their CF and able to prevent or manage their symptoms—even during activity—were more likely to have reported developing strategies to enable them to be active. These findings indicate that identifying and modifying beliefs about the controllability of CF may facilitate attempts to promote physical activity.

The concept of ‘normality’ is often used to explain the extent to which people adapt to or accept life with a chronic condition.48–50 The term is most frequently used to describe the process of adjustment following a diagnosis of a chronic condition (eg, cancer),48 and numerous typologies of normality have been proposed.51 52 For example, individuals may develop a ‘normality’ in which the condition is integrated and accepted.51 At the other end of the spectrum, individuals accept a disrupted normality in which maintaining a normal life is rejected due to the overwhelming disruptions caused by the condition. Situated between these extremes is a group of individuals who strive to present a ‘normal life’ despite the severity of symptoms or disruption.49 While this literature is usually referring to individuals with a biographical disruption,51 the concept of normality still appears to be relevant to individuals with CF. The seven studies included in this review provide examples of individuals for whom normality includes their CF. Such individuals were able to partake in physical activity through adaptations when necessary (eg, resting or slowing the pace of the activity). There were also examples of individuals who, in an attempt to appear normal, would avoid activity due to its potential to accentuate differences between the young person with CF and their peers. However, within the current review there was a group of individuals who used physical activity as a way of enabling normality, engaging in physical activity because it made them feel normal. While this review has highlighted the influence of perceptions of normality in physical activity behaviour, further exploration of this concept in relation to individuals with CF is clearly needed.

A key barrier to physical activity identified though this review was that of competing priorities. Young people with CF described reduced time for enjoyable activities as a result of a demanding treatment regime. This combined with an increased sense of urgency for spending time with friends and family and achieving key milestones as a result of a reduced life expectancy resulted in less enjoyable pursuits (such as physical activity) being overlooked. Promotion of physical activity as an enjoyable and social pastime could reduce the tension associated with these competing demands.

Perceiving physical activity as fun, enjoyable and enhancing autonomy appeared to be more important for long-term engagement in physical activity than the associated health benefits. This is consistent with the self-determination theory53 which suggests that motivation for a particular activity can be either intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation describes engagement in activities for the pleasure or satisfaction it provides. Extrinsic motivation, in contrast, describes motivation for activities for an external outcome, for example, avoiding ill-health, or pressure from healthcare professionals. While intrinsic motivation is the most autonomous form of motivation, extrinsic motivation may be more or less autonomous. Motivation that is not autonomous is less likely to be sustained over time.54 Self-determination theory has informed the development of a multitude of successful interventions aiming to promote physical activity among a wide range of populations55–57 and the current research highlights that use of this theory in informing interventions to support physical activity among individuals with CF may also be beneficial.

In accordance with the socioecological model, the roles of the social and physical environments were identified as key influencers in the physical activity of young people. The role of the family in influencing perceptions of physical activity and physical activity behaviour among young people is widely accepted.58 Studies included in the present review provide additional support for the role of the family in acting as role models and providing tangible and emotional support to promote and maintain physical activity. However, in order to support young people to be active, families must have the necessary knowledge regarding the importance of physical activity, in addition to knowing how to support young people to be active. They must also have the physical and psychological capacity to be able to support young people to be active, and this could be a challenge when taking into consideration the stress and emotional consequences of having a young child with a chronic condition. Indeed, some parents reported using physical activity to manage their own stress and anxiety. This strongly supports a strategy that involving families in attempts to promote physical activity among young people with CF is critical.

Environmental factors, including access to social facilities and safe spaces have been identified as key influencers in physical activity behaviour.24 Congruent with previous research, the current review identified a lack of facilities as a key barrier to physical activity. However, active travel, particularly when young people were able to do this independently, was identified as a facilitator to physical activity.22 A focus on facilitating and supporting active travel may be beneficial.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this work is that it brings together the qualitative literature that has provided an in-depth account of the barriers and facilitators to physical activity among young people with CF. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-synthesis to do so for this population. Through synthesising this work, we have presented barriers and facilitators to physical activity among a wider sample of young people with CF than could be obtained through individual qualitative studies alone, and with greater depth than can be obtained through quantitative studies.

It must be noted that the perspective brought to the analysis is psychological. Interpretation of the data in relation to the Self-determination Theory may have been influenced by prior exposure to these theories. We acknowledge that consideration of other theories may have resulted in the data being organised and presented differently. However, every effort was made to ensure that all themes were clearly representative of the data as presented in the original studies.

Sixteen potentially relevant studies were only reported in abstract format. Although we contacted authors to request full unpublished reports where available, none had plans to develop manuscripts of their work in time for the work to be included in this review. While the included studies were of moderate to high quality, reflexivity was often poorly described. Future studies should provide greater detail about the relationship between the researcher and the research process. As three of the studies included in the review were authored by one research team, this may reflect a smaller distribution of participants, potentially reducing the transferability of findings.

We acknowledge that barriers and facilitators to physical activity are likely to be influenced by demographic factors (age, gender, location) and current levels of physical activity. The primary research included in the current review did not attempt to explore variations between these populations, therefore we were limited in our ability to explore these issues in the current analysis. For example, only one study required participants to monitor or report their physical activity levels, and this study did not link activity levels to the quotes provided.

Implications for research and practice

This review provides further support for the idea that individuals with CF are likely to engage with activities that are fun and enjoyable rather than focusing exclusively on the health benefits of physical activity. In order to promote long-term, sustainable engagement with physical activity, healthcare professionals should encourage and support young people to identify activities that they find enjoyable, rather than focusing exclusively on the health benefits associated with physical activity. Involving families in the process could also be beneficial, as families are able to provide tangible and emotional support, as well as dealing with organisational demands. However, this review also identified a range of psychosocial issues, such as stress and poor coping skills, that may hinder physical activity among young people and their families. Engagement in physical activity is likely to increase if healthcare professionals can facilitate a supportive environment in which physical activity can occur. This could necessitate dealing with psychological issues (eg, stress or coping skills) before attempting to promote physical activity.

The number of potentially relevant articles identified through our search strategy implies that promotion of physical activity is an important topic and is of interest to clinical care teams. We had to reject 16 potentially relevant documents as they were only available in abstract form. Developing methods for sharing or disseminating theses data would be beneficial as it would ensure that researchers do not duplicate work that has already been completed and would also allow completed work to be included in systematic reviews or syntheses so that they may be used to inform clinical practice.

Conclusions

In summary, this is the first synthesis of qualitative work that has explored barriers and facilitators to physical activity among young people with CF. Previous reviews have been unable to identify intervention characteristics that influence physical activity behaviour. It is therefore unclear how best to support physical activity among this population. This review provides detailed information on the physical, psychological and social influences of physical activity behaviour, thus providing numerous targets for future interventions. Identifying and targeting issues at any of these levels could facilitate promotion of physical activity among this population. Our key recommendation would be that healthcare professionals work with their patients to identify barriers and facilitators to physical activity that are specific to each individual. We suggest that the findings from this review may provide a framework that healthcare practitioners may use to structure discussions relating to physical activity, and could potentially highlight some barriers (or facilitators) that may not previously have been considered.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted on behalf of Youth Activity Unlimited, A Strategic Research Centre of the UK Cystic Fibrosis Trust. Members of Youth Activity Unlimited are: Professor Craig Williams (PI), Dr Alan Barker, Dr Sarah Denford; Professor Eleanor Main, Dr Sarah Rand, Ms Helen Douglas (University College London, UK); Dr Mandy Byron (Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, UK); Professor Anne Holland, Dr Narelle Cox, Dr Paul O’Halloran (La Trobe University, Australia); Dr Kelly Mackintosh, Dr Melita McNarry, Ms Mayara Silviera (Swansea University, UK); Dr Jane Schneiderman, Dr Greg Wells, Ms Jessica Caterini (Hospital for Sick Children, Canada).

Footnotes

Contributors: This study was designed by SD with considerable input from SvB, CAW and PO. Studies were identified by SD with inputs from colleagues with expertise in systematic reviewing. Data were extracted and analysed by SD and SvB with inputs from PO and CAW. The manuscript was prepared by SD with considerable input from SvB, CAW and PO. All authors approved the final manuscript prior to publication.

Funding: This work was supported by the Cystic Fibrosis Trust Strategic Research Centre: grant number 008 and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Circle of Care Award. The funders had no involvement in the research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation About cystic fibrosis, 2017. Available: https://www.cff.org/What-is-CF/About-Cystic-Fibrosis/

- 2. The Cystic Fibrosis Trust UK cystic fibrosis registry 2016 annual data report. London: The Cystic Fibrosis Trust, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. The Cystic Fibrosis Trust Cystic Fibrosis Insight Survey - Report on the 2017 and 2018 surveys. London: The Cystic Fibrosis Trust, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4. The Cystic Fibrosis Trust Standards of care and good clinical practice for the physiotherapy management of cystic fibrosis. 3rd Edn edition London: The Cystic Fibrosis Trust, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pianosi P, Leblanc J, Almudevar A. Peak oxygen uptake and mortality in children with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2005;60:50–4. 10.1136/thx.2003.008102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Radtke T, Nevitt SJ, Hebestreit H, et al. . Physical exercise training for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;11:CD002768 10.1002/14651858.CD002768.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gulmans VA, de Meer K, Brackel HJ, et al. . Outpatient exercise training in children with cystic fibrosis: physiological effects, perceived competence, and acceptability. Pediatr Pulmonol 1999;28:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Orenstein DM, Hovell MF, Mulvihill M, et al. . Strength vs aerobic training in children with cystic fibrosis: a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2004;126:1204–14. 10.1378/chest.126.4.1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barak A, Wexler ID, Efrati O, et al. . Trampoline use as physiotherapy for cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr Pulmonol 2005;39:70–3. 10.1002/ppul.20133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Orava C, Fitzgerald J, Figliomeni S, et al. . Relationship between physical activity and fatigue in adults with cystic fibrosis. Physiother Can 2018;70:42–8. 10.3138/ptc.2016-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Backström-Eriksson L, Bergsten-Brucefors A, Hjelte L, et al. . Associations between genetics, medical status, physical exercise and psychological well-being in adults with cystic fibrosis. BMJ Open Respir Res 2016;3:e000141 10.1136/bmjresp-2016-000141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Denford S, Mackintosh KA, McNarry MA, et al. . Promotion of physical activity for adolescents with cystic fibrosis: a qualitative study of UK multi disciplinary cystic fibrosis teams. Physiotherapy 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2019.01.012. [Epub ahead of print: 26 Jan 2019]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stevens D, Oades PJ, Armstrong N, et al. . A survey of exercise testing and training in UK cystic fibrosis clinics. J Cyst Fibros 2010;9:302–6. 10.1016/j.jcf.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rowbotham NJ, Smith S, McPhee M, et al. . EPS1.9 question CF: a James Lind alliance priority setting partnership in cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2017;16:S38 10.1016/S1569-1993(17)30282-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rowbotham NJ, Smith S, Leighton PA, et al. . The top 10 research priorities in cystic fibrosis developed by a partnership between people with CF and healthcare providers. Thorax 2018;73:388–90. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nixon PA, Orenstein DM, Kelsey SF. Habitual physical activity in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001;33:30–5. 10.1097/00005768-200101000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, et al. . Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1077–86. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Selvadurai HC, Blimkie CJ, Cooper PJ, et al. . Gender differences in habitual activity in children with cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child 2004;89:928–33. 10.1136/adc.2003.034249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nixon PA, Orenstein DM, Kelsey SF, et al. . The prognostic value of exercise testing in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1785–8. 10.1056/NEJM199212173272504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cox NS, Alison JA, Holland AE. Interventions to promote physical activity in people with cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Respir Rev 2014;15:237–9. 10.1016/j.prrv.2014.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Craig P, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: reflections on the 2008 MRC guidance. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:585–7. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Condello G, Puggina A, Aleksovska K, et al. . Behavioral determinants of physical activity across the life course: a "DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity" (DEDIPAC) umbrella systematic literature review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017;14:58 10.1186/s12966-017-0510-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Allender S, Cowburn G, Foster C. Understanding participation in sport and physical activity among children and adults: a review of qualitative studies. Health Educ Res 2006;21:826–35. 10.1093/her/cyl063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martins J, Marques A, Sarmento H, et al. . Adolescents' perspectives on the barriers and facilitators of physical activity: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Health Educ Res 2015;30:742–55. 10.1093/her/cyv042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. . Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yardley L, Morrison L, Bradbury K, et al. . The person-based approach to intervention development: application to digital health-related behavior change interventions. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e30 10.2196/jmir.4055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, et al. . From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol 2008;57:660–80. 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prasad SA, Cerny FJ. Factors that influence adherence to exercise and their effectiveness: application to cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2002;34:66–72. 10.1002/ppul.10126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moran F, Bradley J. Incorporating exercise into the routine care of individuals with cystic fibrosis: is the time right? Expert Rev Respir Med 2010;4:139–42. 10.1586/ers.10.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rand S, Prasad SA. Exercise as part of a cystic fibrosis therapeutic routine. Expert Rev Respir Med 2012;6:341–52. 10.1586/ers.12.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sallis J, Owen N. Ecological models of health behavior : Glanz K, Rimer B, Viswanath K, Theory, research and practice. 64 5th ed. CA, USA: Joissey-Bass, 2015: 43–725. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Critical appraisal skills programme: making sense of evidence, 1993. Available: https://casp-uk.net/

- 34. Moolchaem P, Liamputtong P, O’Halloran P, et al. . The lived experiences of transgender persons: a Meta-Synthesis. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv 2015;27:143–71. 10.1080/10538720.2015.1021983 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Duggleby W, Holtslander L, Kylma J, et al. . Metasynthesis of the hope experience of family caregivers of persons with chronic illness. Qual Health Res 2010;20:148–58. 10.1177/1049732309358329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:1 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fereday J, MacDougall C, Spizzo M, et al. . "There's nothing I can't do--I just put my mind to anything and I can do it": a qualitative analysis of how children with chronic disease and their parents account for and manage physical activity. BMC Pediatr 2009;9:1 10.1186/1471-2431-9-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moola FJ, Faulkner GEJ. 'A tale of two cases:' the health, illness, and physical activity stories of two children living with cystic fibrosis. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2014;19:24–42. 10.1177/1359104512465740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moola FJ, Faulkner GEJ, Kirsh JA, et al. . Developing physical activity interventions for youth with cystic fibrosis and congenital heart disease: learning from their parents. Psychol Sport Exerc 2011;12:599–608. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moola FJ, Faulkner GEJ, Schneiderman JE. "No time to play": perceptions toward physical activity in youth with cystic fibrosis. Adapt Phys Activ Q 2012;29:44–62. 10.1123/apaq.29.1.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Happ MB, Hoffman LA, Higgins LW, et al. . Parent and child perceptions of a self-regulated, home-based exercise program for children with cystic fibrosis. Nurs Res 2013;62:305–14. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182a03503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Swisher AK, Erickson M. Perceptions of physical activity in a group of adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J 2008;19:107–14. 10.1097/01823246-200819040-00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shelley J, Fairclough SJ, Knowles ZR, et al. . A formative study exploring perceptions of physical activity and physical activity monitoring among children and young people with cystic fibrosis and health care professionals. BMC Pediatr 2018;18:335 10.1186/s12887-018-1301-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hagger MS, Orbell S. A meta-analytic review of the Common-Sense model of illness representations. Psychol Health 2003;18:141–84. 10.1080/088704403100081321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sylvain C, Lamothe L, Berthiaume Y, et al. . How patients' representations of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes inform their health behaviours. Psychol Health 2016;31:1129–44. 10.1080/08870446.2016.1183008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bucks RS, Hawkins K, Skinner TC, et al. . Adherence to treatment in adolescents with cystic fibrosis: the role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. J Pediatr Psychol 2009;34:893–902. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bury M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol Health Illn 1982;4:167–82. 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Knafl KA, Deatrick JA. How families manage chronic conditions: an analysis of the concept of normalization. Res Nurs Health 1986;9:215–22. 10.1002/nur.4770090306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Taylor RM, Gibson F, Franck LS. The experience of living with a chronic illness during adolescence: a critical review of the literature. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:3083–91. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02629.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sanderson T, Calnan M, Morris M, et al. . Shifting normalities: interactions of changing conceptions of a normal life and the normalisation of symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis. Sociol Health Illn 2011;33:618–33. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01305.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Frank A. The wounded story Teller: body, illness and ethics. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. perspectives in social psychology. New York: Plenum, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory: a macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne 2008;49:182–5. 10.1037/a0012801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Russell KL, Bray SR. Promoting self-determined motivation for exercise in cardiac rehabilitation: the role of autonomy support. Rehabil Psychol 2010;55:74–80. 10.1037/a0018416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Silva MN, Vieira PN, Coutinho SR, et al. . Using self-determination theory to promote physical activity and weight control: a randomized controlled trial in women. J Behav Med 2010;33:110–22. 10.1007/s10865-009-9239-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sweet SN, Fortier MS, Strachan SM, et al. . Testing a longitudinal integrated self-efficacy and Self-Determination theory model for physical activity post-cardiac rehabilitation. Health Psychol Res 2014;2:1008 10.4081/hpr.2014.1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Brown HE, Atkin AJ, Panter J, et al. . Family-Based interventions to increase physical activity in children: a systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obes Rev 2016;17:345–60. 10.1111/obr.12362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-035261supp001.pdf (28.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035261supp002.pdf (32.2KB, pdf)