Abstract

Introduction

Mental health issues appear as a growing problem in modern societies and tend to be more frequent in big cities. Where increased evidence exists for positive links between nature and mental health, associations between urban environment characteristics and mental health are still not well understood. These associations are highly complex and require an interdisciplinary and integrated research approach to cover the broad range of mitigating factors. This article presents the study protocol of a project called Nature Impact on Mental Health Distribution that aims to generate a comprehensive understanding of associations between mental health and the urban residential environment.

Methods and analysis

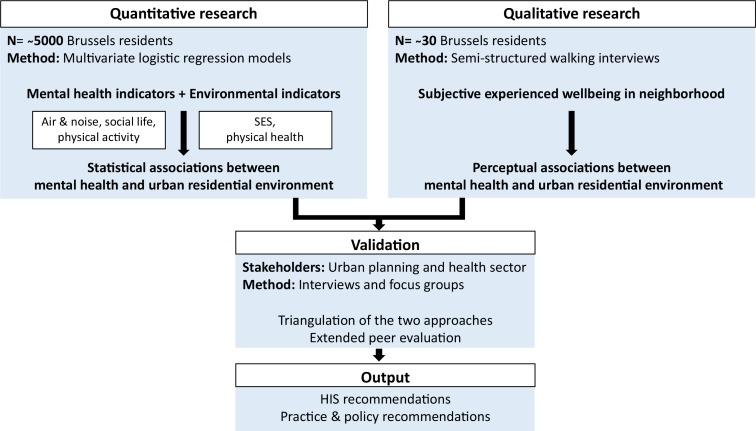

Following a mixed-method approach, this project combines quantitative and qualitative research. In the quantitative part, we analyse among the Brussels urban population associations between the urban residential environment and mental health, taking respondents’ socioeconomic status and physical health into account. Mental health is determined by the mental health indicators in the national Health Interview Survey (HIS). The urban residential environment is described by subjective indicators for the participant’s dwelling and neighbourhood present in the HIS and objective indicators for buildings, network infrastructure and green environment developed for the purpose of this project. We assess the mediating role of physical activity, social life, noise and air pollution. In the qualitative part, we conduct walking interviews with Brussels residents to record their subjective well-being in association with their neighbourhood. In the validation part, results from these two approaches are triangulated and evaluated through interviews and focus groups with stakeholders of healthcare and urban planning sectors.

Ethics and dissemination

The Privacy Commission of Belgium and ethical committee from University Hospital of Antwerp respectively approved quantitative database merging and qualitative interviewing. We will share project results with a wide audience including the scientific community, policy authorities and civil society through scientific and non-expert communication.

Keywords: urban environment, mental health, mixed method

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The Nature Impact on Mental Health Distribution (NAMED) project mixes quantitative and qualitative methods to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the association between urban residential environment and mental health.

The NAMED project investigates various components of mental health and of the urban residential environment using complementary indicators. However, only indicators describing the physical and not the social residential environment (such as neighbourhood cohesion, neighbourhood criminality) are considered.

The NAMED project combines subjective and objective environmental indicators. However, the cross-sectional study design does not allow ruling out reverse causation for associations found between the subjective environmental and mental health measures.

The NAMED project couples urban environment indicators and mental health indicators at individual level to capture the complexity of this relationship influenced by very local environmental factors and individual attributes. However, available data do not allow investigating other relevant environmental exposures than the one to the residential environment.

The NAMED project includes a validation phase in which key stakeholders and experts can evaluate the methodological approach of the project and direct recommendations relevant from a societal practice perspective.

Introduction

According to WHO, depression alone affects around 300 million people worldwide.1 In Belgium, the Health Interview Survey (HIS) underlined a deterioration of the psychoemotional health of the population: the proportion of respondents presenting psychological difficulties increased from 25% to 32% between 2008 and 2013. These included anxiety, depressive disorder or sleep disorders. Strikingly, these are more prevalent in the Brussels-Capital Region (BCR) (40%) than in the two other regions Wallonia (35%) and Flanders (29%).2

It is now well established that the nature, prevalence and age of onset of mental disorders vary according to demographic, socioeconomic and cultural factors.2–6 Several international studies analysed links between the urban environment and mental health from different research angles by looking at the urban social or physical environment.7 With respect to the urban social environment, concentrations of low socioeconomic status (SES), low social capital or social segregation have been studied as social risk factors for mental health in cities.7–9 Feelings of community attachment and social cohesion are shown to improve mental health, where neighbourhood disorder, such as crime and violence, is associated with poor mental health.9–15 In Belgium, the occurrence of psychosocial difficulties is generally higher in cities.2

Associations between the urban physical environment and mental health have been investigated in terms of urban design, noise pollution and air pollution.16–18 Regarding the urban design, evidence has increased on the positive impact of urban green and blue spaces on mental health.16 19 20 After controlling for confounding factors, significant associations were found between (1) depression, anxiety, visits to mental health specialists, and stress and access to green space (2) between depression and park size (3) between depression, anxiety, perceived risk for poor mental health and visits to mental health specialists and surrounding greenness and (4) between perceived mental health and perceived greenness.21–26 Besides the natural environment, several studies investigated associations between mental health and the built environment in terms of walkability, access to care and housing quality.23 27 28 For instance, increased walkability has been associated with a decreased incidence of depression and enhanced physical activity.23 27 Indoor and outdoor noise are found to be significantly associated with self-reported mental health problems or mental disorders.13 16 29 Also air pollution has been found to be associated with depressive symptoms. However, many studies did not take into account confounding factors.17 29

Although a broad range of research has found some trends in associations between mental health and urban environment, conclusions still tend to differ or to be contradictory across studies.12 20 29–31 This may be explained by different research limitations. First, most studies rely on a single indicator such as the ‘General Health Questionnaire 12’ (GHQ-12 items) to describe mental health or focus on a single aspect such as depression.7 9 14 20 29 32 33 This makes it difficult to grasp diverse degrees of severity and to compare across studies. Second, the strict use of subjective environmental measures in some studies make it difficult to conclude on whether participants with mental health issues are more likely to report negatively on their environment or that negative environmental aspects contribute to mental illnesses (reverse causation).10 12 14 15 Studies including objective environmental measures make often use of a limited set of indicators developed at census area unit level, which makes it difficult to compare results across different study contexts and reflect lived experiences of the residential urban environment.14 16 20 32 Exposures to surrounding green, air pollution and other factors of the urban environment are generally spatially correlated.34 However, most of the epidemiological studies assessing the relation between the urban environment and mental health have evaluated only one of these environmental exposures, ignoring the potential confounding or interaction effects between noise, air pollution and green space. Finally, a general restriction to quantitative methods limits the development of a comprehensive understanding of mechanisms underlying associations between the urban environment and mental health.12 15 20 Considering the increasing urbanisation worldwide, it becomes clear that further research on which characteristics of the urban environment may be beneficial or detrimental for mental health, on pathways involved, and on the impact of social, economic and cultural factors is needed.35 In addition, there is a growing need to evaluate the quality and relevance of research results for practice.

The Nature Impact on Mental Health Distribution (NAMED) is a Belgian 4-year project (2017–2021) that aims to further investigate the associations and underlying mechanisms between mental health and urban residential environment in the BCR. To overcome the weaknesses of conducting only quantitative research, where individual understanding of these associations is limited, or only qualitative research, where the results cannot be generalised, the project applies a mixed-method approach. In NAMED, the quantitative research relies on HIS data and analyses associations between the urban residential environment and mental health, taking SES and physical health into account. To do so, we adapt, develop and combine a broad set of both subjective and objective indicators to overcome the limitations of previous research. We assess the mediating role of physical activity, social life, noise and air pollution in associations with mental health and urban environment. The qualitative research involves interviews with Brussels dwellers with the goal to analyse how they perceive and experience the urban environment in relation to mental health. The combined approach allows a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms, including direct effects (stress buffer, recovery, etc), indirect effects (physical activity, social life, noise and air pollution) and impacts of individuals’ perceptions and experiences.

Eventually, in a validation stage, we discuss and evaluate together with experts and stakeholders the quantitative and qualitative results. The mixed-method approach presented in this paper is conducted by a multidisciplinary team, including epidemiologists, geographers, general practitioners, and environmental and social scientists. The integration of both research parts will result in a comprehensive understanding of urban determinants of mental health, from individual to community scales. Based on the research results, NAMED intends to draw practice and policy recommendations for urban planning and health management. NAMED will make suggestions for extension of the HIS (new approaches derived from the qualitative methods, new wordings or new questions relating to urban environment and mental health). Besides, the involvement of representatives of the urban planning sectors will guide a better integration of mental health issues in new health-promoting urban development projects. The following research questions are addressed:

Is there an association between the urban residential environment and mental health in the BCR using objective and subjective indicators? (Quantitative research part)

How do people living in the BCR perceive and experience their urban residential environment in association with their mental health? (Qualitative research part)

How can the project results contribute to practice and policy? (Validation part)

Methodology

Study area

The study area is the BCR. The BCR is one of the three administrative regions of Belgium (besides Wallonia and Flanders) and comprises 19 municipalities. The restriction to the BCR is motivated by the high prevalence of mental health problems, but also by the large representativeness and distribution of the HIS participants for 2008 and 2013. The large cities in Flanders and Wallonia have much less HIS-participants than the BCR. Since we include qualitative interviews, it is not realistic to propose an investigation in the large cities of every region in Belgium. The focus on the BCR was also motivated by the available geographic data. Very detailed spatial information has been collected, digitised and made available to the general public for the BCR, which is not the case for the other regions of Belgium, Flanders and Wallonia. The existence of a rich dataset, both in HIS participation and geographical detail, was a strong argument for choosing BCR as our study region. The BCR is 161.38 km² large and counts 1 198 726 inhabitants (1 January 2018) which means an average density of 7428 inhabitants/km².36 It can be considered a green urban region as 54% of its surface area is covered by vegetation (forest, public green spaces, urban trees, private gardens, etc).37 However, a clear contrast in vegetation cover exists between the centre and the outer parts of the Region. Besides difference in access to green, the neighbourhoods are highly diverse in population density, median income, household composition. BCR is characterised by a high cultural diversity (40% non-Belgian nationality) and a mixed use of language (most spoken: French, English and Flemish).36 38

Mixed-method approach

The NAMED project applies a mixed-method approach, combining quantitative and qualitative research structured into a convergent parallel design. This mixed-method approach is conducted by combining disciplines and requires a constant interaction between the different researchers in order to adapt their investigations to others’ findings. The main level of interaction between the quantitative and qualitative research part occurs at the results interpretation step, which allows to understand if qualitative findings converge or diverge from quantitative ones. Besides this data triangulation, the validation part also involves key stakeholders and experts to reflect throughout the project on scientific and practice relevance. The three research parts are explained in detail in following sections (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the working plan of NAMED with the main characteristics of each research part. HIS, Health Interview Survey; NAMED, Nature Impact on Mental Health Distribution; SES, socioeconomic status.

Mental health and the urban residential environment are approached in a complementary manner in both research parts. In the quantitative research part, mental health is determined by the mental health indicators for psychological distress, energy level, anxiety, depression, sleeping problems, suicidal ideation, addictive substance consumption present in the HIS. The urban residential environment is described by (1) self-reported assessment of participant’s dwelling (such as humidity) and neighbourhood (such as accumulation of rubbish) present in the HIS; (2) objective indicators for buildings, network infrastructure and green environment developed for the purpose of this project. In the qualitative research part, mental health is assessed using the subjective well-being of the participants in association with their urban residential environment. The urban residential environment is covered by the subjective description of characteristics and places in the neighbourhood that play an important role in the participant’s well-being.

The quantitative research part

The quantitative research part uses the data collected within the Belgian HIS in 2008 and 2013. It consists in (1) retrieving HIS respondents’ home address, (2) developing relevant indicators characterising each home address in terms of urban environment, air and noise pollution using geographical information systems (GIS) and (3) coupling these environmental indicators with HIS data. Based on this enriched database, this part investigates then the associations between mental health and urban environment in a cross-sectional way, taking into account socioeconomic and lifestyle factors.

Study population

The study population for the quantitative part includes the inhabitants of the BCR aged 15 and older who participated in the HIS in 2008 (n=2831) or in 2013 (n=2532). The HIS is a reoccurring national cross-sectional epidemiological survey carried out by the Belgian research institute for health (Sciensano) in partnership with the Belgian statistical office (Statbel). It has been organised every 5 years since 1997. For each survey, approximately 10 000 individuals are selected from the National Register based on a random sampling scheme stratified by region (including 3000 individuals from the BCR) and by province, ensuring representativity of the Belgian population. Any person officially residing in Belgium is likely to be selected.

Data collection and indicators selection

Mental health, socioeconomic, lifestyle and perceived environmental data

During each survey, detailed information is collected through face-to-face and self-administered questionnaires. The face-to-face questionnaire collects information on general health status, reduced mobility, use of healthcare services, SES, nutrition and perception on environmental characteristics, such as air pollution and noise disturbance. The self-administered questionnaire is used to collect data on mental health and on sensitive topics, such as alcohol and drug use. Both questionnaires include questions adapted from validated screening tools. A description of the questionnaires can be found online.39 Mental health, SES, lifestyle and perceived environmental data are retrieved from the Belgian HIS. The selection of relevant indicators for the NAMED project is based on a literature review, on the variables distribution and on a factor analysis of mixed data (FAMD) on all mental health variables. We selected all the mental health indicators available in the HIS database that were based on internationally validated scales. We only excluded the eating disorders since it is a very specific disorder for which we did not find anything in the literature review. The indicator on suicidal attempts in the past 12 months was also excluded given the too few cases reported. Thus, the mental health status of each HIS respondent is described by following indicators:

The prevalence of psychological distress across the population. This categorical indicator is based on the ‘GHQ-12’ for general well-being.

The respondents’ energy level. This indicator is based on the ‘Vitality scale (VT-4 items) for positive mental health’ from the Short-Form Health Survey 36. This index contains four items measuring the respondents’ vital energy level and is used to assess the positive dimension of mental health. This score is recommended by the European project on developing common instruments for health surveys.

The prevalence of anxiety disorders, the prevalence of depressive disorders and the prevalence of sleeping disorders. These dichotomised indicators are based on the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) subscales (42 items) for depression, anxiety and sleeping problems.

The subjective health, the reported depression in the past 12 months and the reported suicidal ideation in the past 12 months based on isolated variables.

Indicators on risky behaviours are also considered through variables related to addictive substances consumption (‘Problematic alcohol consumption’ and ‘Lifetime prevalence of cannabis use’).

Based on the results of the FAMD, all the indicators were kept in order to cover both positive and negative dimensions of mental health and diverse degrees of severity. The use of these standardised variables facilitates comparisons across studies.

To describe respondents’ SES, eight indicators are selected: age, gender, country of birth, household composition, highest educational level within the household, professional activity, employment status and reported household income. From the lifestyle data, indicators are further selected to describe physical health, social life and physical activity. Regarding respondents’ physical health, three indicators are identified: body mass index, reported problems in mobility and presence of one or more long-standing illnesses, chronic conditions or handicaps. SES and physical health are included as confounders. The indicators ‘appreciation of social life’ and ‘level of health enhancing physical activity’ are included as potential mediators.

Respondents’ perception of environmental problems at their residence is approached through 18 indicators in three different domains.

Nuisance in the neighbourhood is described by: traffic volume; traffic speed; accumulation of rubbish; vandalism; graffiti or deliberate damage of property and lack of access to parks or other green or recreational public places.

Nuisance at home is characterised by: air pollution; bad smell from industry; bad smell from others sources (sewer, waste, etc); vibrations from road, metro, tram, train or air traffic; noise from road, train, tram, metro, air traffic, factories and neighbours.

Problems linked to the dwelling are approached by: unable to keep the home warm enough in the winter; problem of humidity or mould in the dwelling; smoke inside the dwelling every day or almost every day; and overcrowded household.

These indicators potentially contain information on environmental degradations not captured by GIS data and provide a good opportunity to assess the level of environmental stress felt by the respondents.

Indicators of urban environment

The urban environment indicators include buildings, network infrastructure and green environment. The building structure is described in terms of two-dimensional footprint, spatial organisation, height. The network infrastructure is described by the street network supporting daily mobility. And the green environment is described in terms of urban trees, open green public spaces, and private gardens.

We make use of two datasets available for the BCR: an open database, called UrbIS (CIRB-CIBG 2016) providing a set of cartographic data specific to the region and Brussels-Environment (the local environment and energy administration) providing vegetation data.37 40 The vegetation data were computed by Van de Voorde et al 37 with high-resolution remote sensing data using a normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) threshold value of 0.275.37

We process these data using GIS to develop indicators describing the residential environment of each HIS respondent. We provide indicators at three different scales to represent the individual's experience at home, on the street, or in the neighbourhood:

At the scale of the building of the respondent: view of green and garden coverage.

At the scale of the street in which the respondent lives: canyon effect (height/width ratio); street corridor effect; linear density of urban trees; and visible street vegetation coverage.

At the scale of the neighbourhood of the respondent (1000 m): typology of urban fabric and green coverage.

As specified above, a typology of 12 urban fabrics (combination of 21 indicators of urban environment) has been created to highlight the urban environment as perceived by pedestrians freely moving on the street network.41 This typology and other indicators enable us to approach the concept of walkability by taking into account the presence of sidewalks, urban street trees, design of the street (canyon and street corridor effect), visible street vegetation coverage.42

Air quality data

Data on HIS respondents’ exposure to air pollution are obtained from the national monitoring system supervised by the Belgian Interregional Environment Agency. Regional background levels of particular manner (PM) PM10, PM2.5, black carbon (BC), ozone (O3) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) exposure (μg/m3) are determined for each HIS respondent based on their home address. A land use regression model is used for background concentrations taking into account land cover data obtained from satellite images (Coordination of Information on the Environment (CORINE) Land Cover data set) and daily pollution data from fixed monitoring stations. Then, this model is superimposed with a dispersion model to account for point and line sources (industrial smokestacks, road traffic). This results in daily exposure values with a high spatial and temporal resolution.43–45 Saenen et al 45 demonstrated the accuracy of the model to estimate a person’s real exposure by showing that modelled PM2.5 and BC at the residence correlates with internal exposure to BC particles measured in urine.45 Using the daily estimates, we calculate annual averages of PM10, PM2.5, BC, O3 and NO2 exposure levels (μg/m³) at HIS respondents’ home address as indicators for air quality.

Noise data

Noise information is derived from the European noise database, a system supervised by the European Commission (directive 2002/49/EC, 2002). It aims at identifying and mapping noise from road, rail and air traffic and allows an assessment of population exposure across Europe according to standardised procedures, including harmonised noise indicators: day–evening–night noise level (Lden) and night noise level (Lnight). The Lden indicator is an average sound pressure level over all days (12 hours), evenings (4 hours) and nights (8 hours) in a year. Lnight is the A-weighted long-term average sound level determined over all the night periods (8 hours) of a year. As associations between mental health and noise pollution are expected to occur as a result of long-term exposure, it is generally accepted that the most relevant parts of the whole day or night, which especially account for the time when a person is at home, are correctly attributed when using average indicators like Lden or Lnight.46 Since 2002, measures are done for urban areas counting more than 200 000 inhabitants, every 5 years, at the most exposed façades of buildings. We will combine noise maps available for the years 2006 and 2011 with the geographical coordinates of the participants’ residence to estimate Lden and Lnight noise values in 5 dB(A) intervals. Since the evolution in noise pollution between 2006 and 2011 was very weak, we can assume that average noise levels in 2008 and 2013 will not differentiate significantly on a 2-year difference from the collected noise data.47

Data analysis

In a first step, we take full advantage of the HIS dataset itself by investigating the associations between indicators describing the respondents’ mental health and indicators describing the respondents’ perceived environment through bivariate analyses. Additionally, we describe the distribution of SES across environmental indicators in order to assess potential ‘environmental inequalities’. These descriptive analyses permit to identify potential vulnerable groups (likely and among others: socially deprived, isolated persons, teenagers) that should receive a greater attention. This first step results in crude distribution patterns to be further investigated with more complex statistical techniques.

In a second step, we merge the database on environmental indicators previously described with individual data of HIS respondents. Linkage is done at the individual level and implies to temporarily geolocate the home address of all respondents (‘x,y’ coordinates) at the time they participated in the survey. The relations between all the environmental variables are assessed through a principal component analysis. Based on the merged dataset and mental health indicators as previously described, we analyse relationships between mental health and urban environment characteristics using multivariate logistic regression models. In order to take into account the complex relationships between all the environmental variables, single exposure and multi exposure models are performed. Models will be fitted with increasing adjustments for covariates: respondents’ SES, physical health and lifestyle factors. We use structural equation modelling which provides a flexible framework to assess the potential mediating role of physical activity, social life, and noise and air pollution in the associations between mental health and urban environment.48 We check results for robustness with sensitivity analyses by, for example, including only participants living at the same address for more than 1 year, and using the environmental factors as continuous and categorical variables in the analysis.

In a third step, we look at the interrelations between the perceived and the objective exposure (lack of access to parks, air and noise pollution) using general linear models and classification and regression trees. This allows to assess the share of subjectivity in respondents’ answers.

Data protection

All institutions handling data ensure their protection against leak, theft, misuse or degradation. In addition to current protection measures already implemented to protect HIS data, we consider and discuss additional controls such as specific encryption and special back up with the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) team and data safety advisor.

The qualitative research part

We apply a qualitative descriptive approach and undertake research within a relativist ontology and subjectivist epistemology. This approach holds the view that reality is subjective and stresses the active role and contribution the researcher plays in the research process. The use of a qualitative description approach is most appropriate for this study as we seek to discover and understand a phenomenon, time and resources are limited, and this study is part of a mixed-method project.49 In this project, walking semistructured interviews are employed as data collection method. This method allows to better understand and perceive respondents’ daily interactions in local contexts.50

Study population

To capture a diversity of inhabitants in the BCR, we aim for a maximum variation sample size in the recruitment of the participants. To do so, we apply a purposeful sampling frame where we aim to reach a diverse sample by selecting diverse study areas, local organisations and participants. Five study areas representing a diversity in urban fabric, population density, access to green and median income are defined. In each area, we contact a diversity of local organisations involved in either environmental, sociocultural or health-related activities. In each organisation, the project is communicated to the inhabitants through an oral introduction, posters and folders. This recruitment strategy intends to reach a varied sample in terms of age, gender, education level, employment status and cultural background. Only participants skilled in Dutch, French or English and a minimum age of 18 years can participate. Based on sample size recommendations to reach theoretical saturation when using a semistructured interview approach, the sample size is estimated to consist of 30 participants.51 Regarding the complexity of the project theme and the aimed heterogeneity of respondents, this sample size seems appropriate because of the exploratory nature of this research and the focus on identifying underlying ideas about the topic.

Data collection

We invite the participants for semistructured interviews, which consist in an open discussion following a guide of topics to be explored.52 Topics tackled within the NAMED project include: residential street; neighbourhood places, characteristics and changes; reasons to walk in neighbourhood; future vision on neighbourhood. All topics are questioned in relation to participant’s well-being. This list serves the interviewer to keep the flow of the conversation and to remind the participant of the interview purpose. However, the participants are stimulated to lead the conversation as much as possible to minimise steering by the interviewer. These discussions take the form of a walking interview. This approach, also called go-along or walk-along interview, provides detailed insights into the meanings and practices people associate with their living environment.53 Furthermore, it helps to reduce steering the conversation by the interviewer and the typical power dynamics that exist between the interviewer and interviewee.54 At the beginning of the interview the participants are asked to guide the walk along a route in the neighbourhood that allows to discover the places and characteristics that play an important role in their well-being. The interviews are audio recorded and Global Positioning System (GPS) tracked (with consent). The interviews are estimated to take maximally 2 hours, including an introduction, the walk and a discussion.

Data analysis

We apply a thematic analysis on transcripts of the audio-recorded interviews, involving a three-stage coding process: descriptive coding, interpretative coding and finally coming to overarching themes and their relationships.55 56 We check the themes appearing in interviews from the same area and across different areas for similarities and differences in the perception and experiences of the urban residential environment in relation to subjective well-being.

Data protection

We pseudonymise the transcripts so the identity of the interviewed participants is not disclosed during the presentation of the research results.

The validation part

Data triangulation

Data triangulation is defined as ‘a process of validating research conclusions by examining a relationship from different methodological angles’.57 Quantitative results are triangulated with qualitative ones to get a better understanding of the associations between the urban residential environment and mental health. The qualitative results can support a better understanding of mechanisms that underlie associations identified in the quantitative part. If both results provide at some points mutual confirmation, we can consider the results more valid.57 In the case that results diverge from each other, new research questions and hypotheses can emerge.

Extended peer evaluation

Throughout the project, we consult key stakeholders from local, regional, and national health and environment authorities as well as institutions and experts from the international research community.58 This allows to evaluate the quality of the project and to produce outcomes relevant not only from a scientific perspective but also from a societal practice perspective. We consult these actors through individual interviews and focus groups. Involvement of experts and stakeholders through participatory processes is a well-established practice for environmental management and policy making.59–62 Modern views on governance underline that managing the living environment is no longer exclusively seen as the sole responsibility of governmental institutions.60 It is perceived more as an interplay of different societal actors, including governmental institutions, local communities, and professional and stakeholder groups.63 When conducting and assessing research findings in the perspective of urban planning, health management and policy recommendations, the involvement of a diversity of actors seems vital in order to have an encompassing and well-informed view.

dissemination

The team will present and discuss research results in the form of maps, explanatory models, and storytelling and share them with a wide audience including the scientific community, policy authorities and the civil society through international peer-reviewed publications, scientific conferences and non-expert communication. We will also make specific efforts to translate and communicate research results to the general public through media, non-profit organisations and specific events (including media, non-profit organisations and specific events). The NAMED website (https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/projects/named/) provides an overview of the project, progress, actualities and publications.

Patient and public statement

For the qualitative part, local organisations and experts are involved to reflect on the interview design. The local organisations support participants recruitment by promoting the project to their members or visitors. The interviews involve a diverse sample of inhabitants of the BCR.

For the validation part, stakeholders and experts are invited for focus groups to discuss research results. Their inputs will support final reporting of the project results and implications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to all members of the follow up committee who provide relevant input throughout the project. We acknowledge the full HIS team of Sciensano and the Belgian statistical office, Statbel, for their technical support during the process of database merging and linking.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception of the mixed-method study protocol. LL, ML, RR, HB and HK are responsible for the development and implementation of the qualitative research part and evaluation part in consultation with IP, ST, MG, NS, EDC, IT and TN. IP, ST, MG, NS, EDC, IT and TN are responsible for the development and implementation of the quantitative research part in consultation with LL, RR, HB and HK. AG and AVN are no longer active on the project but contributed greatly to the study design and gave their reflections on the manuscript. LL provided a first draft and adapted the manuscript to the comments from all other authors and reviewers. IP and ST were responsible for the adjustments to the quantitative research part in the manuscript. LL and ST proofread the manuscript and made final adjustments. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office (BELSPO), grant number BR/175/A3/NAMED.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Approval for the data merging in the quantitative research part has been given by the Privacy Commission of Belgium (19/01/2018, reference number 02/2018). The walking interviews with Brussels residents in the qualitative research part has been approved by the ethical committee from the University Hospital of Antwerp (Alternative Ethical Review board of the University of Antwerp) (26/11/2018, reference number 18/44/503).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization [Internet] Mental disorders, 2018. Available: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders [Accessed 18 Noc 2019].

- 2. Drieskens S, Charafeddine R, Demarest S, et al. HISIA: Belgian Health Interview Survey - Interactive Analysis. Brussels: Sciensano; https://hisia.wiv-isp.be/ (cited 2019 Nov 18). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States and sociodemographic characteristics: the epidemiologic catchment area study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993;88:35–47. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03411.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European study of the epidemiology of mental disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004;109:21–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Merikangas KR, He J-P, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49:980–9. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bijl RV, Ravelli A, van Zessen G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorder in the general population: results of the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (nemesis). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998;33:587–95. 10.1007/s001270050098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gruebner O, Rapp MA, Adli M, et al. Cities and mental health. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2017;114:121–7. 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Desjarlais R, Eisenberg L, Good B, et al. World mental health: problems and priorities in low-income countries. USA: Oxford University Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Paczkowski MM, Galea S. Sociodemographic characteristics of the neighborhood and depressive symptoms. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2010;23:337–41. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833ad70b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dalgard OS, Tambs K. Urban environment and mental health. A longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry 1997;171:530–6. 10.1192/bjp.171.6.530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chu A, Thorne A, Guite H. The impact on mental well‐being of the urban and physical environment: an assessment of the evidence. J Public Ment Health 2004;3:17–32. 10.1108/17465729200400010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clark C, Myron R, Stansfeld S, et al. A systematic review of the evidence on the effect of the built and physical environment on mental health. J Public Ment Health 2007;6:14–27. 10.1108/17465729200700011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guite HF, Clark C, Ackrill G. The impact of the physical and urban environment on mental well-being. Public Health 2006;120:1117–26. 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mair C, Diez Roux AV, Galea S. Are neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidence. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:940–6. 10.1136/jech.2007.066605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Toma A, Hamer M, Shankar A. Associations between neighborhood perceptions and mental well-being among older adults. Health Place 2015;34:46–53. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ma J, Li C, Kwan M-P, et al. A multilevel analysis of perceived noise pollution, geographic contexts and mental health in Beijing. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1479 10.3390/ijerph15071479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buoli M, Grassi S, Caldiroli A, et al. Is there a link between air pollution and mental disorders? Environ Int 2018;118:154–68. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.05.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCay L, Bremer I, Endale T, et al. Urban design and mental health In: Mental health and illness in the City, 2017: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lorenc T, Clayton S, Neary D, et al. Crime, fear of crime, environment, and mental health and wellbeing: mapping review of theories and causal pathways. Health Place 2012;18:757–65. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gascon M, Triguero-Mas M, Martínez D, et al. Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:4354–79. 10.3390/ijerph120404354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sugiyama T, Leslie E, Giles-Corti B, et al. Associations of neighbourhood greenness with physical and mental health: do walking, social coherence and local social interaction explain the relationships? J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:e9 10.1136/jech.2007.064287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stigsdotter UK, Ekholm O, Schipperijn J, et al. Health promoting outdoor environments--associations between green space, and health, health-related quality of life and stress based on a Danish national representative survey. Scand J Public Health 2010;38:411–7. 10.1177/1403494810367468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nutsford D, Pearson AL, Kingham S. An ecological study investigating the association between access to urban green space and mental health. Public Health 2013;127:1005–11. 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beyer KMM, Kaltenbach A, Szabo A, et al. Exposure to neighborhood green space and mental health: evidence from the survey of the health of Wisconsin. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:3453–72. 10.3390/ijerph110303453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cox DTC, Shanahan DF, Hudson HL, et al. Doses of neighborhood nature: the benefits for mental health of living with nature. Bioscience 2017;117:147–55. 10.1093/biosci/biw173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. South EC, Hohl BC, Kondo MC, et al. Effect of greening vacant land on mental health of community-dwelling adults: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e180298 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cohen-Cline H, Turkheimer E, Duncan GE. Access to green space, physical activity and mental health: a twin study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:523–9. 10.1136/jech-2014-204667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Evans GW. The built environment and mental health. J Urban Health 2003;80:536–55. 10.1093/jurban/jtg063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rautio N, Filatova S, Lehtiniemi H, et al. Living environment and its relationship to depressive mood: a systematic review. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2018;64:92–103. 10.1177/0020764017744582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moore THM, Kesten JM, López-López JA, et al. The effects of changes to the built environment on the mental health and well-being of adults: systematic review. Health Place 2018;53:237–57. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Benita F, Bansal G, Tunçer B. Public spaces and happiness: evidence from a large-scale field experiment. Health Place 2019;56:9–18. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Melis G, Gelormino E, Marra G, et al. The effects of the urban built environment on mental health: a cohort study in a large northern Italian City. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:14898–915. 10.3390/ijerph121114898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gong Y, Palmer S, Gallacher J, et al. A systematic review of the relationship between objective measurements of the urban environment and psychological distress. Environ Int 2016;96:48–57. 10.1016/j.envint.2016.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Markevych I, Schoierer J, Hartig T, et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ Res 2017;158:301–17. 10.1016/j.envres.2017.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hartig T, Mitchell R, de Vries S, et al. Nature and health. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:207–28. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Statbel, the Belgian statistical office statbel.fgov.be, 2018. Available: statbel.fgov.be/en [Accessed cited 2019 Nov 18].

- 37. Van de Voorde T, Canters F, Chan JC. Mapping update and analysis of the evolution of non-built (green) spaces in the Brussels capital region. final report (report no: ActuaEvol/09). Brussels: Cartography and GIS Research Group, Department of Geography, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hermia JP, Sierens A. Belges et étrangers en Région bruxelloise, de la naissance aujourd’hui. Brussels: IBSA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sciensano Questionnaires, 2019. Available: https://his.wiv-isp.be/SitePages/Questionnaires.aspx [Accessed 18 Nov 2019].

- 40. CIRB-CIBG UrbIS data, 2019. Available: https://cirb.brussels/fr/nos-solutions/urbis-solutions/urbis-data [Accessed 6 May 2019].

- 41. Araldi A, Fusco G. From the street to the metropolitan region: pedestrian perspective in urban fabric analysis. Environ Plan B Urban Anal City Sci 2019;46:1243–63. 10.1177/2399808319832612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Maghelal PK, Capp CJ. Walkability: a review of existing pedestrian indices. URISA J 2011;23. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Janssen S, Dumont G, Fierens F, et al. Spatial interpolation of air pollution measurements using CORINE land cover data. Atmos Environ 2008;42:4884–903. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.02.043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lefebvre W, Degrawe B, Beckx C, et al. Presentation and evaluation of an integrated model chain to respond to traffic- and health-related policy questions. Environ Model Softw 2013;40:160–70. 10.1016/j.envsoft.2012.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Saenen ND, Bové H, Steuwe C, et al. Children's urinary environmental carbon load. A novel marker reflecting residential ambient air pollution exposure? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196:873–81. 10.1164/rccm.201704-0797OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. World Health Organization Environmental noise guidelines for the European region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Styns Evaluatie van de gezondheids- en economische gevolgen van het globale verkeersgeluid in het Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest. BIM, collectie factsheets, thema geluid. Brussels: Leefmilieu Brussel, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gunzler D, Chen T, Wu P, et al. Introduction to mediation analysis with structural equation modeling. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 2013;25:390–4. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2013.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bradshaw C, Atkinson S, Doody O. Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Glob Qual Nurs Res 2017;4:233339361774228 10.1177/2333393617742282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kusenbach M. Street phenomenology: the go-along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnography 2003;4:455–85. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Morse JM. Determining sample size. Qual Health Res 2000;10:3–5. 10.1177/104973200129118183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. London: Sage, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 53. O'Brien L, Morris J, Stewart A. Engaging with peri-urban woodlands in England: the contribution to people's health and well-being and implications for future management. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:6171–92. 10.3390/ijerph110606171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Carpiano RM. Come take a walk with me: the "go-along" interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being. Health Place 2009;15:263–72. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Maguire M, Delahunt B. Doing a thematic analysis: a practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. AISHE J 2017;9. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Molina-Azorin JF, Bergh DD, Corley KG, et al. Mixed methods in the organizational sciences: taking stock and moving forward. Organ Res Methods 2017;20:179–92. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Keune H, Koppen G, Morrens B, et al. Extended peer evaluation of an analytical Deliberative decision support procedure in environmental health practice. Eur. j. risk regul. 2014;5:25–35. 10.1017/S1867299X00002920 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Renn O. Participatory processes for designing environmental policies. Land use policy 2006;23:34–43. 10.1016/j.landusepol.2004.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jordan A. The governance of sustainable development: taking stock and looking forwards. Environ Plann C Gov Policy 2008;26:17–33. 10.1068/cav6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Reed MS. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: a literature review. Biol Conserv 2008;141:2417–31. 10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Brown G, de Bie K, Weber D. Identifying public land stakeholder perspectives for implementing place-based land management. Landsc Urban Plan 2015;139:1–15. 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hooghe L, Marks G. Unraveling the central state, but how? types of multi-level governance. Am Polit Sci Rev 2003;97:233–43. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.