Abstract

Objectives

This investigation expected to validate the psychometric properties of the modified seven-item Kessler psychological distress scale (K7) for measuring psychological distress in healthy rural population of Bangladesh.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Narail district, Bangladesh.

Participants

A random sample of 300 adults of age 18–90 years were recruited. Face-to-face interviews were conducted between July and August 2018 using an Android phone installed with a mobile data collection application known as CommCare.

Outcome measure

Validation of the K7 was the major outcome. Sociodemographic factors were measured to assess for Differential Item Functioning to check if the tool functions equally in different factors. Rasch analysis was carried out for the validation of the K7 scale in the healthy rural population of Bangladesh. RUMM2030 was used for the analyses.

Results

Results showed good overall fit, as indicated by a non-significant item-trait interaction (χ2=44.54, df=28, p=0.0245) compared with a Bonferroni adjusted p value of 0.007. Both item fit (mean=0.30, SD 1.22) and person fit residuals (mean=–0.18, SD 0.85) showed perfect fit. Reliability was very good as indicated by a Person Separation Index=0.85 and Cronbach’s alpha=0.89. All individual items were ordered thresholds. The K7 scale showed adequate reliability, unidimensionality and was free from local dependency. The K7 scale also showed similar functioning for adults and older adults, males and females, no education and any level of education, and at least some financial instability versus no financial instability.

Conclusions

Validation of K7 scale confirmed that the tool is suitable for measuring psychological distress among the rural Bangladeshi population. Further research should validate the K7 scale in different rural settings in Bangladesh to determine a valid cut-off score for assessment of severity levels of psychological distress. The K7 scale should also be tested in other developing countries where sociodemographic characteristics are similar to those of Bangladesh.

Keywords: Kessler psychological distress scale, Rasch analysis, Validation, Rural Bangladesh

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides the first reliable data on the Kessler K7 scale from a general population of a typical rural district of Bangladesh.

This study used primary data on a K7 scale and application of the Rasch analysis technique was applied to validate the K7 scale instead of classical test theory.

The data were collected through face-to-face interviews to increase the accuracy of data.

The study provides a unique opportunity to assess psychological distress in a rural population of Bangladesh by using reasonably fewer items.

The potential drawback of this study is that it is based on a single-occasion collection of data from a rural district in Bangladesh which prevents test–retest evaluation or comparison of alternate versions of the same measures.

Background

Globally, one out of every four individuals is influenced by mental or psychological distress at some point in their lives.1 Almost 66% of individuals experiencing psychological distress fail to look for assistance because they were unaware of, or neglect, their disorder.2 Due to the rapid growth of mental disorders, there is a need to identify risk conditions quickly in a cost-effective manner.3 Early diagnosis of psychological distress has been seen as an essential measure to guarantee successful, focused, effective and targeted intervention for patients experiencing psychological distress.4 In recent years, researchers have primarily been interested in early diagnosis of psychological distress and used tools with a very limited number of items for measuring psychological distress among the general population.5 Therefore, the development and continued validation of the tools used for measuring psychological distress is critical, especially for early detection of psychological instability.

Typically, large epidemiological studies of mental health have used detailed and interviewer-administered diagnostic interviews; replicating this method is considered cost-effective for the general population.6 A variety of these diagnostic screening interviews are now accessible, and these include the Diagnostic Interview Schedule,7 Composite International Diagnostic Interview8 and the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview.9 Dimensional measures of non-specific psychological distress have come to take on new importance because it distinguishes people based on severity level rather than purely on diagnosis. Over the last three decades, large-scale epidemiological studies used screening measures to provide a quick measure of the prevalence of psychological distress.10–13 However, most of the tools have an extensive list of items which have been limited to the use of widely accepted tools aimed at the screening of psychological distress among the general population.

The Kessler 10-item scale (K10) is an exception. Developed by Professors Kessler and Mroczek in 1992, K10 was designed to be used in the United States National Health Interview Survey as a brief measure of non-explicit psychological distress along with the anxiety–depression spectrum.14 The K10 and the six-item scale K6 was developed concurrently with experimental instruments for assessing psychological distress in people with a variety of mental disorders.15 The six items for K6 is included in K10. The K10 and the K6 have been translated and validated in at least 14 countries worldwide.6 16–18 The K10 tool was initially developed to recognise the levels of non-specific psychological distress in the general population and was employed in many countries including Australia, Canada and the USA.15 19–21 The WHO’s World Mental Health Survey also used this tool.22 The tool has also identified a substantial association with severe mental illnesses.23 As such, clinicians recommend utilisation of the K10 and the K6 to screen for psychological distress.24 25 Although both scales have been validated with various populations and languages, research has indicated that the factor structures of the K10 and the K6 scales differ. For example, one study outlined discrepancies between the K6’s one-factor and two-factor structures16 while another study outlined discrepancies between the K10’s two-factor and four-factor structures.17 In addition, both the K10 and the K6 cross-cultural validity was not employed in any rural settings including the rural populations of Bangladesh. Such variations in factor structures suggest that further research is needed on the psychometric properties of the K10 and the K6 instruments.

Bangladesh is a densely populated country with a population of 167 million people; around 65% of them live in rural areas.26 27 Psychological distress has been found to be a significant public health concern especially in rural areas.28–31 The prevalence of mental disorders varies notably in rural areas, ranging from 6.5% to 31% of the total population, conceivably due to the utilisation of diverse conventions, different measuring tools and various meanings associated with mental disorders.32 Further, there has been no culturally sensitive tool available for rapid screening of psychological distress in Bangladesh. Recently, Uddin et al validated the K10 scale using the Rasch analysis technique in a rural area of Bangladesh and proposed a modified version of a seven-item K7 scale. The K7, which is a subset of the K10, proved to be robust containing a 4-point Likert-type scale instead of the 5-point scale of the original K10. The modified K7 version followed all assumptions of Rasch analysis and produced a unidimensional tool for measuring psychological distress.

The K7 scale provides additional benefits. One is related to brevity offering ease of administration, and the other is low cost to measure psychological distress through a shortened version of the K10 scale. Given the widespread use of the K10 and the K6 scales, including the translated Bengali versions of K10 scale,18 it is noteworthy that no empirical validation studies with Bengali-speaking populations have been reported in the literature review. The culturally validated instrument of the K7 scale can provide an increasingly productive resource for healthcare services and can be applied in other developing countries with similar sociodemographic characteristics. However, further validation of the K7 scale with its four-response categories is required to be used for rural populations of Bangladesh. Therefore, the current study aims to provide validation of the modified version of the K7 scale for potential application within healthy population settings in rural Bangladesh.

Materials and methods

Study population

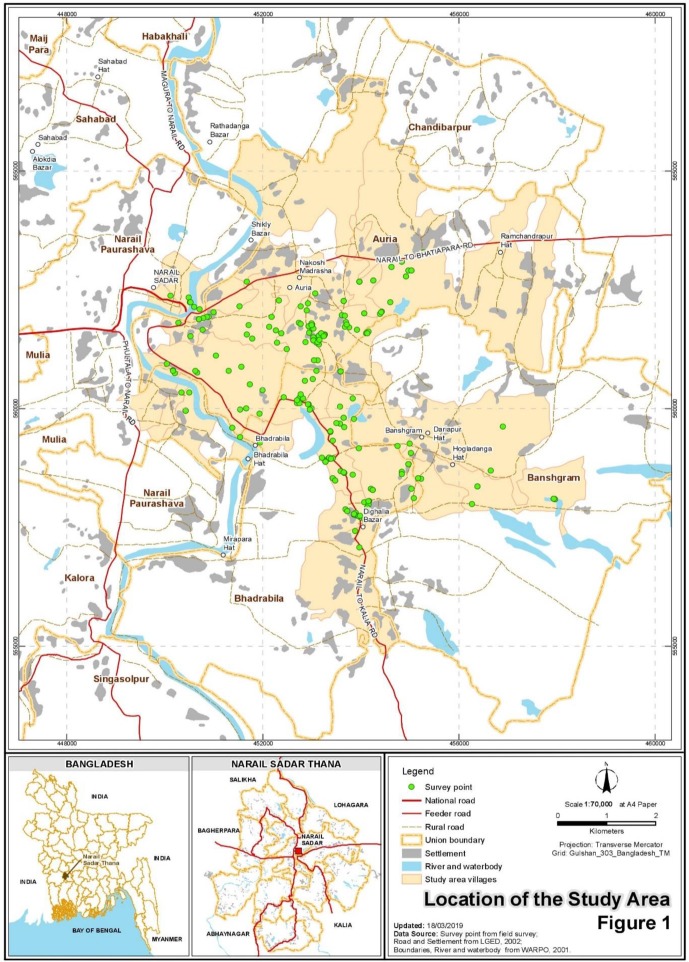

Bangladesh is a nation of 167 million individuals divided into 64 districts.26 The male:female ratio (48.9 to 51.1) was consistent in all over in Bangladesh.33 Around 72.9% of individuals attained primary education or above as opposed to 27.1% had no education of the national population.34 With respect to the availability of funds, the population having insufficient funds some or most of the time accounted for 23.2% in Bangladesh.35 Adult participants aged 18 to 90 years were selected from the Narail Upazilla, which is located around 200 km southwest of Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh. Interviews were conducted between July and August of 2018. The study area includes a specific geographical area and 300 survey points of data collection. Data were gathered from three unions (Auria, Banshgram and Bhardabila) of the region. This has been described in detail in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study location that includes a geographical area and data collection points.

Sample size and statistical power

A sample size of 300 adults of age 18–90 was used for this study. This sample size is appropriate for a Rasch examination since large samples can potentially result in type 1 error that falsely dismisses an item for not fitting the Rasch model.36 A sample size of 300 is viewed as sufficiently substantial to ensure 99% confidence that the item difficulty would be within ±½ logit of its stable value.37

Sampling frame

The cross-sectional study recruited a multistage cluster random sample of 320 participants from the rural district Narail of Bangladesh in the period of July–August 2018. Data were collected from three unions (the smallest rural administrative units) out of nine unions, excluding the four which were selected previously from the 13 unions of Narail Upazilla.38 The selected unions are Auria, Banshgram and Bhardabila. One village (the smallest territorial and social unit for administrative and representative purposes), from each of the chosen unions, was randomly selected at the second level. The selected villages were Baliadanga, Fulshor and Rogunathpur. Two paras (further divisions of the village) from each selected village were randomly chosen at the third level. In total, 40 adults (18–59 years old) and 40 older adults (60–90 years old) from each of the villages/wards were interviewed. Interviewers used a mobile data collection platform CommCare on their android phone to collect data from the respondents. To mitigate the effect of selection bias, 320 respondents were used with an equal proportion of adults and older adults, further partitioned into gender. This study excluded 20 participants randomly as 300 participants were deemed sufficient for the Rasch Measurement Theory.

Data collection using CommCare and its advantage over using a printed questionnaire

Mobile data collection is a method employed to collect qualitative and quantitative inputs via a mobile device (eg, mobile phone, tablet, etc). The introduction of mobile devices has mitigated streamlining and making them more economical and less time consuming.39 Other benefits include minimisation of human errors, speeding up reporting, increased flexibility in deploying programmatic changes and provision of accurate location information.40 With the correct implementation of the mobile data collection tool, these benefits can all be successfully implemented.41 CommCare is a customisable, mobile platform, which empowers non-developers to build mobile applications for data collection.42 CommCare allows mobile applications to run offline where gathered information can be transmitted to CommCareHQ as internet connectivity becomes accessible.43

The current study followed a strict protocol to ensure a smooth launch after the CommCare application was finalised by pre-testing before training began.44 The application was pilot tested with 30 people. The testing found some minor problems associated with respondents not understanding the application correctly. These concerns were addressed through an upgraded version of the application which was then distributed for final data collection.

Modified Kessler psychological distress scale (K7)

The K7 measures developed asked respondents to consider how regularly they encountered of depressive and anxiety symptoms in the preceding 4 weeks before screening. Respondents were asked to express how often the following seven symptoms occurred: they felt nervous; so nervous that nothing could calm them down; hopeless; restless or fidgety; so restless that they could not sit still; so depressed that nothing could cheer them up; everything was an effort.18 Items were rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale. The answer to each question was allocated to a value of 1, 2, 3 or 4: “none of the time”, “a little of the time”, “some or most of the time” or “all the time”, respectively.

Outcome measure

The K7 scale is the main outcome measure for assessing psychological distress using Rasch analysis. Demographic details were collected for age, gender and level of education and socioeconomic conditions.

Rasch model

The Rasch model was named after Danish mathematician Georg Rasch.45 The model shows what is required for reactions to items if estimation (at the measurement level) is to be accomplished most accurately. Two versions of the Rasch model are available: dichotomous45 and polytomous.46 In this case, the polytomous Rasch model was used. The Rasch model consists mainly of two forms, the rating scale model and the partial credit model, which can be used with polytomous results. The partial credit model is the norm under RUMM2030, which does not restrict threshold parameters and enables them to differ by item.47 The likelihood ratio check, which is available in the RUMM2030 program, tests unregulated parameterisation (partial credit model) towards reparameterisation. The non-statistical result shows that the definition of the rating scale is to be used, although statistically significant results indicate that the partial credit model should be used.48 An analysis was undertaken, and a significant finding was found which encourages the use of the partial credit model.

The Rasch analysis used in this investigation was conducted using the software package RUMM2030.49 The Rasch model makes a few hypotheses that should be assessed to guarantee an instrument has Rasch properties. The most ordinarily evaluated Rasch suspicions are (1) unidimensionality, (2) local independence and (3) invariability. Local independence means that the scores are related to each other only through the construct, whereas unidimensionality means that only one construct is being measured and the invariance criterion implies that generally an instrument should function in the same way for all individuals.50 51 As indicated by the Rasch demonstration, the overall fit of the model is defined by χ2 item–trait interaction statistics.52 With non-significance, a Bonferroni-corrected level of 0.007 (0.05/7 items) indicates adequate fit.53–56 Item–person interaction statistics are exhibited as z-statistics (mean=0 and SD 1) and show ideal fit. Individual item fit (IFR) measurements incorporate the residuals satisfactorily when inside the range ±2.5 and a non-significant χ2 value.57

A ‘threshold’ parameter is characterised by two response options where either response is equally likely. Disordered thresholds demonstrate that the respondents are not able to segregate between the response’s choices. Disordered thresholds result in item misfit and can be redressed by combining two neighbouring response options.58 Following the principal component analysis (PCA) of the residuals, the associations between items and the first PCA variables are used to describe two subsets of products. The independent t-test is then used to determine the difference between the two subsets. The individual estimates, with a non-significant result or the lower bound variance of the binomial distributions by 5%, indicate no evidence of multidimensionality.59 The person–item residuals correlation matrix can be used to determine whether there is any local dependency between the items, and correlations less than 0.3 are generally considered to be acceptable.48 Differential item functioning (DIF) investigates whether items operate a similar function across different groups. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) has been carried out for each item that compares scores across each group factor level (age, sorted as either adult (18 to 59 years) or older adult (60 to 85 years), sex (male or female), education (no education or at least primary) and socioeconomic conditions low (insufficient funds most/some of the time) and high (balance/sufficient funds all the time)) and across construct levels. DIF was found to be present if the ANOVA was significant with the Bonferroni correction (Bonferroni adjusted p value of 0.05/7=0.007).60 61 Rasch examination also gives a marker of reliability. In RUMM2030, this is given by the Person Separation Index (PSI). The PSI of the Rasch analysis consists of indices developed as an approximation of the proportion of the true or error-free variance. This applies throughout the distribution of person estimates relative to the sum of this variance and error variance in these estimates. With Rasch measurement, instead of reliability indices, the person separation index is used. However, the person separation index is analogous to Cronbach’s alpha (CA).62 A value near 1 shows high internal consistency and a value under 0.7 demonstrates low scale reliability.63

Patient and public involvement

Study participants were generally people without any disease. Public involvement for the research was obtained primarily informing the district commissioner, district police super, civil surgeon and various public representatives such as the Chairman of the union Parishad. A pilot survey was conducted and a focus group discussion involving the general public was arranged as the questionnaire was developed. To maintain an approximately equal number of male and female participants, one female was interviewed immediately after each male participant. Participants were not involved in the recruitment and conduct of the study. Results will be disseminated via community briefs and presented at national and international conferences. Patient consent form can be found in online supplementary materials.

Results

Table 1 describes the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants by gender (male vs female). The mean (SD, range) age of the participants was 52.0 years (15.6, 18–90). A considerably large proportion (45.0%) of the populations did not have any formal education, with only 1.3% attaining a bachelor’s degree or above. The socioeconomic condition for most respondents (about 41.3%) was occasional financial instability, 32.3% experienced a precarious financial situation, 25.3% experienced balance and 1.0% held sufficient funds most of the time.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristic of gender in Narail Upazila in Bangladesh

| Characteristic | Total (300) | Female (150) | Male (150) |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age (in years) | 52 (15.7) | 51.7 (15.5) | 52.8 (16.0) |

| Age in group | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Adult | 150 (50.0) | 75 (50.0) | 75 (50.0) |

| Elderly | 150 (50.0) | 75 (50.0) | 75 (50.0) |

| Level of education (no of years schooling) | |||

| No education | 135 (45.0) | 80 (53.3) | 55 (36.7) |

| Primary (1–5) | 80 (26.7) | 36 (24) | 44 (29.3) |

| Secondary (6–9) | 64 (21.3) | 31 (20.7) | 33 (22) |

| SSC or HSC pass (10–12) | 17 (5.7) | 3 (2.0) | 14 (9.3) |

| Degree or equivalent (13–16) | 4 (1.3) | 0 | 4 (2.7) |

| Socioeconomic condition | |||

| Insufficient funds most of the time | 97 (32.3) | 62 (41.3) | 35 (23.3) |

| Insufficient funds some of the time | 124 (41.3) | 50 (33.3) | 74 (49.3) |

| Balance | 76 (25.3) | 37 (24.7) | 39 (26) |

| Sufficient funds most of the time | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.3) |

HSC, Higher Secondary School Certificate; SSC, Secondary School Certificate.

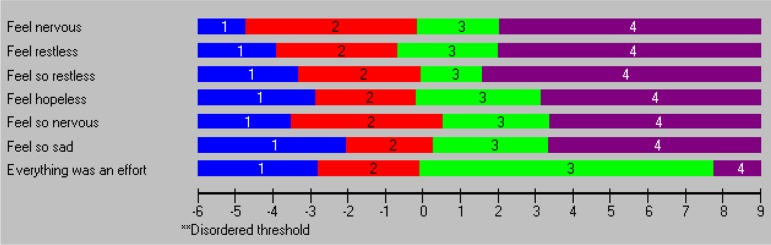

The validation of the K7 scale showed good overall fit to the Rasch model with the Bonferroni adjusted p value of 0.007 (χ2=44.54, df=28, p=0.0245). The item fit residual (IFR) (mean=0.30, SD 1.22) and the person fit residual (mean=−0.18, SD 0.85) were within the acceptable range (table 2). All seven items were found to have ordered thresholds (figure 2), suggesting the respondents have no difficulty differentiating between the response’s choices with the 4-point Likert-type scale used in the K7 scale.

Table 2.

Overall model fit statistics of the K7 scale

| Model fit statistics | Total sample n=300 |

| Overall model fit, χ2 value | 44.54 |

| Degree of freedom (df) | 28 |

| *P value | 0.0245 |

| Item fit residuals (mean (SD)) | 0.30 (1.22) |

| Person fit residuals (mean (SD)) | –0.18 (0.85) |

| Person Separation Index | 0.85 |

| Coefficient alpha | 0.89 |

| Unidimensionality test (% that goes beyond 95% CI) | 3.7% CI (1.2 to 6.1) |

*The p value 0.007 means significant at level 0.05 because the number of items is seven (0.05/7=0.007). Therefore, any p value greater than 0.007 would be considered non-significant.

Figure 2.

Threshold maps of the K7 scale.

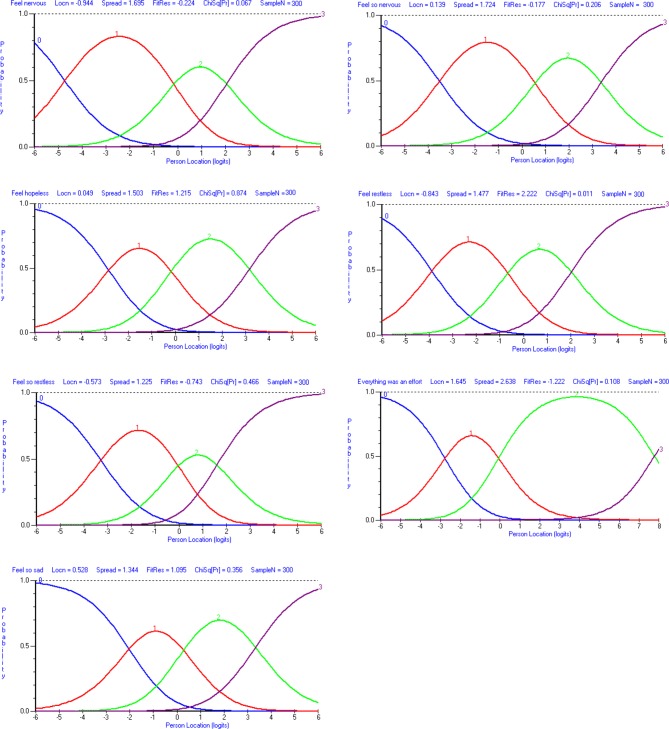

No misfit or overfit items were identified with significant χ2 probability values. There was neither high positive nor high negative residual values (±2.5) observed. All seven individuals’ item fit statistics showed a good fit with the Bonferroni-adjusted p value of 0.007 (table 3). The value of the PSI (0.85) for the original set of seven items with four response categories indicated that the scale worked well to separate persons. The value of Cronbach’s alpha (0.89) of the K7 scale demonstrates good internal consistency. A visual examination of the threshold map (figure 2) showed that the estimates of the thresholds defined the categories in all seven items that formed distinctive regions of the continuum. We also examined the category probability curve in which each response options systematically take turns, showing the highest probability of endorsement (figure 3).

Table 3.

Individuals’ item fit statistics of the K7 scale

| Individuals’ items fit statistics of K7 scale | |||||

| Items | Location | SE | Residual | χ2 | P value |

| Feel nervous | −0.944 | 0.124 | −0.224 | 8.78 | 0.067 |

| Feel so nervous | 0.139 | 0.123 | −0.177 | 5.91 | 0.206 |

| Feel hopeless | 0.049 | 0.112 | 1.215 | 1.23 | 0.874 |

| Feel restless or fidgety | −0.843 | 0.110 | 1.993 | 13.09 | 0.011 |

| Feel so restless | −0.573 | 0.110 | −0.743 | 3.58 | 0.466 |

| Everything was an effort | 1.645 | 0.115 | −1.222 | 7.58 | 0.108 |

| Feel so sad | 0.528 | 0.117 | 1.095 | 4.39 | 0.356 |

Figure 3.

Category probability curve of all the items of the K7 scale.

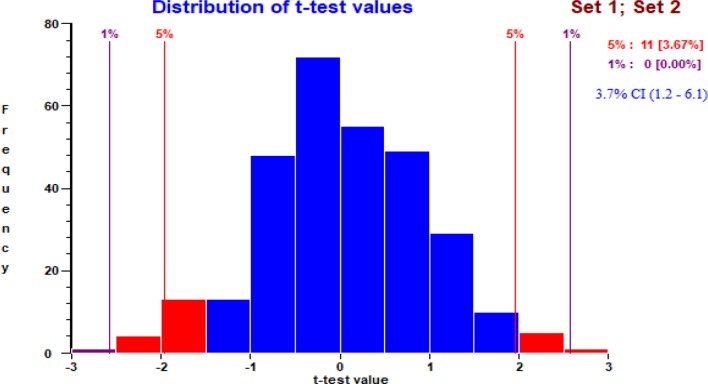

The K7 scale was assessed for DIF across gender (male/female), age (adults/older adults), education (no education/some education) and socioeconomic conditions (low/high) (table 4). No significant DIF was found for any of the items. The unidimensionality of the K7 scale was supported by independent t-tests comparing the person estimates with the PCA of the residuals; our findings indicated that only 3.7% (95% CI 1.2% to 6.1%) of cases showed statistically significant differences (table 2 and figure 4). There were no correlation coefficients above 0.30 on the person–item residual correlation matrix, indicating no local dependency of the items (online supplementary appendix 1).

Table 4.

DIF on age, gender, educational attainment and socioeconomic conditions on K7 scale

| Items | DIF on age | DIF on gender | ||||||

| MS | F | df | P value | MS | F | df | P value | |

| Feel nervous | 1.81 | 2.25 | 1 | 0.135 | 1.26 | 1.55 | 1 | 0.215 |

| Feel so nervous | 1.18 | 1.46 | 1 | 0.228 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 1 | 0.682 |

| Feel hopeless | 0.85 | 0.87 | 1 | 0.351 | 3.45 | 3.61 | 1 | 0.059 |

| Feel restless or fidgety | 0.81 | 0.80 | 1 | 0.373 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 1 | 0.339 |

| Feel so restless | 2.20 | 2.79 | 1 | 0.096 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 1 | 0.655 |

| Everything was an effort | 0.25 | 0.34 | 1 | 0.560 | 0.64 | 0.88 | 1 | 0.351 |

| Feel so sad | 0.77 | 0.79 | 1 | 0.374 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.800 |

| Items | DIF on educational attainment | DIF on socioeconomic conditions | ||||||

| MS | F | df | P value | MS | F | df | P value | |

| Feel nervous | 0.44 | 0.55 | 1 | 0.458 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.939 |

| Feel so nervous | 0.19 | 0.22 | 1 | 0.637 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 1 | 0.521 |

| Feel hopeless | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.897 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 1 | 0.351 |

| Feel restless or fidgety | 0.29 | 0.28 | 1 | 0.597 | 2.18 | 2.15 | 1 | 0.144 |

| Feel so restless | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.883 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 1 | 0.559 |

| Everything was an effort | 1.83 | 2.48 | 1 | 0.117 | 0.48 | 0.65 | 1 | 0.421 |

| Feel so sad | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.917 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.955 |

DIF, differential item functioning; MS, mean square.

Figure 4.

Dimensionality testing of the K7 scale.

bmjopen-2019-034523supp001.pdf (11.8KB, pdf)

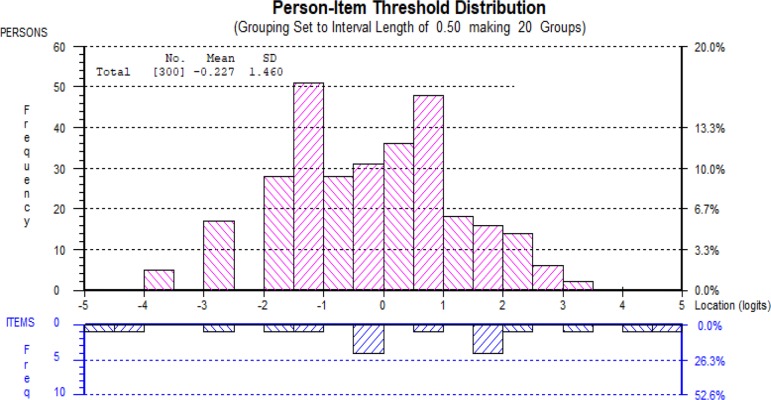

Figure 5 shows the person–item threshold distribution of the K7 scale. The person distribution is shown in the top half and the item thresholds in the bottom half. The average value of individual logit for the K7 scale was −0.227 showing well-targeted persons and items fit for the K7 scale. At the same time, a negative mean value for the K7 measure may suggest that the participant was located at a lower level (eg, psychological distress) than the average level of the scale. Overall, the K7 scale was not too difficult to endorse.

Figure 5.

Person item threshold distribution map of the K7 scale.

Discussion

The current study investigated the psychometric performance of the K7 in a sample of a healthy and rural Bangladeshi population. The inspiration behind the paper was to evaluate the appropriateness of the modified K7 scale (which was prior validated from the K10 scale) survey for measuring psychological distress in rural Bangladesh. This paper includes Rasch examination to investigate a few issues concerning the K7 scale. The article also incorporates the validity of the category scorings framework, the fit of individual items and an evaluation of the potential predisposition of age–sex distribution, education attainment and socioeconomic status.

The K10 scale has recently experienced a thorough psychometric examination in rural Bangladesh prompting the development of a K7 scale to measure psychological distress in rural Bangladesh.18 However, further K7 validation was required to confirm its use in rural settings. From the Rasch examination point of view, the underlying illustrative examination focused on the present rural samples of Bangladesh. The modified K7 scale with four response classifications showed no redundancy (little impact on the scale) and no misfit. Moreover, items were all order thresholds, while scale demonstrated no proof of multidimensionality.

It was stated earlier that the scale would be one-dimensional, an important assumption for the implementation of Item Response Theory (IRT) used to develop K10.15 There is a difference in outcomes for different populations with respect to the dimensional structure of the instrument. In some research, K10 and K6 were proposed as unidimensional scales.15 25 However, other research proposed multidimensional of K10 and K6 scale.16 17 In line of the previous study reported K10 and K6 as unidimensional scales, the findings of the current study further confirm the K7 as a unidimensional scale as it was earlier proposed by Uddin et al.18

Several previous studies conducted around the world did not use Rasch analysis to validate the K10 or K6.14 24 64–69 A comparison of this study with previous studies is limited using PSI. However, Uddin et al 18 used Rasch analysis and developed the K7 scale that would be suitable for rural Bangladesh. The current study recognised that the K7 scale CA was marginally below from the previous estimates of CA, and the PSI was marginally superior to the previous estimates of PSI.18 Moreover, reliability (CA) was high in the current study and consistent with previous research.15 66 70 71 Therefore, the current study results suggest that the translated items measure the same overall construct of psychological distress in rural Bangladesh.

There has been controversy over the DIF associated with gender in psychological distress assessment.72–74 The predominant mental health problems are widely accepted as being associated with the level of education, specifically, as it decreases psychological distress increases.73 75–77 The K7 scale demonstrated no DIF on sex and education level, which supports previous research findings from Australia,73 Japan78 and Bangladesh.18 An investigation led by Kessler et al recorded a conventional arrangement of disparity in the association among age.79 However, different investigations exhibited a stable non-linear connection between age and psychological distress in a few cross-sectional epidemiological studies.79–82 A negative relationship between socioeconomic position and psychological distress has been established in the literature,83 with low socioeconomic status associated with a higher level of psychological distress.84 Although there may still be an association between age/socioeconomic status with psychological distress, the lack of DIF simply means that items function the same way with regards to their psychometric properties, irrespective of age and socioeconomic status group.

To our knowledge, this was the first psychometric assessment on the K7 scale to measure psychological distress in rural Bangladesh. Use of the Rasch estimation demonstrated in this study has strengthened the viability of the K7 scale for measuring psychological distress in rural Bangladesh. The scale demonstrates ordered thresholds with no proof of DIF. Moreover, the scale showed high PSI (0.85) and CA (0.89), which also showed the power of the test for fit. This study provides significant evidence that a complete score of psychological distress can be measured and accelerates the finding of a legitimate cut-off score for rural people in Bangladesh. Building up a cut-off score can help with evaluating the severity levels of psychological distress.

The Rasch examination contributes valuable information on dimensions of psychological distress among the general rural population of Bangladesh. The study was based on a data set with a wide age distribution, where data were collected directly through face-to-face interviews. Interviewers used a mobile data collection platform CommCare to collect data from the respondents to minimising human error and speeding up reporting.44 Further, the K7 scale applied by this method may work as a productive screener for psychological distress across various service settings, including primary and integrated care facilities. This can caution clinicians to patients who may benefit from a psychological distress assessment. The K7 scale can be made openly accessible in any healthcare setting as well as on the web. Given its portability and straightforwardness in both web and paper formats, the K7 scale could be made accessible individuals searching for a self-administered assessment measure.

The primary limitation of this study is that it depends on single-occasion data from people in a rural region of Bangladesh, though we have attempted to validate the K7 scale in the rural area of Narail. The investigation would be improved if a national delegate sample were available. The concern with fit statistics associated with the Rasch analysis is that the greater the sample size, the higher the likelihood of finding the probability of detecting deviations from the Rasch model.85 86 Nevertheless, there are no clear guidelines for sample size when implementing the Rasch Measurement Theory.87 Thus, we used the sample size of 300, which is more favoured.85 Replication studies with large populated samples of Bengali speakers may improve generalisation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study recommended the utilisation of the K7 scale in rural Bangladesh. The research gleaned from this study suggests that a seven-item scale taken from the K10, with four response categories, would offer a robust psychometric scale. The K7 scale satisfies all the assumptions of the Rasch model. Examination of the K7 scale affirmed that the tool could also be used as a standard measure of psychological distress. It could therefore provide a screening instrument for evaluating psychological distress among the rural Bangladeshi population. Further, the tool can be applied in other developing nations experiencing similar sociodemographic attributes. In addition, the tool can be connected within service settings to provide a national dimension using telemedicine, where mental health conditions cannot be analysed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We especially recognise the commitment of Md Mofijul Islam, Serajul Islam and Arzan Hosen for their diligent work in door-to-door data collection. We additionally recognise Dr Mostofa Sarwar for assisting us with building the mobile data collection platform using CommCare for data collection. Finally, we would like to offer our thanks to the investigation members for their wilful interest.

Footnotes

Contributors: MNU and FMAI jointly structured the examination. MNU analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. FMAI supervised and reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript, and read and endorsed its final version.

Funding: The author (MNU) used his own ‘HRD Student Fund’ from the Swinburne University of $A600 for data collection for this research project.

Disclaimer: The funder had no role in the investigation and its planning, information accumulation or examination, interpretation of data or writing of the manuscript.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map in this article does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The ethics committee of the Swinburne University of Technology Human Ethics Committee (SHR Project 2015/065 extended endorsement got in July 2018) has granted ethics approvals.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The datasets used and/or analysed for the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

- 1. World Health Organization The World Health Report: 2001. Mental health: new understanding, new hope. 2001 Geneva: WHO, 2001: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Svenaeus F. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 17 5th edition Medicine Health Care and Philosophy, 2014: 241–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fard K, Hudgens RW, Welner A. Undiagnosed psychiatric illness in adolescents. A prospective study and seven-year follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978;35:279–82. 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770270029002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Costello EJ. Early detection and prevention of mental health problems: developmental epidemiology and systems of support. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2016;45:710–7. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1236728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sunderland M, Mahoney A, Andrews G. Investigating the factor structure of the Kessler psychological distress scale in community and clinical samples of the Australian population. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2012;34:253–9. 10.1007/s10862-012-9276-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ, et al. . Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2011;20:62 10.1002/mpr.333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, et al. . National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38:381–9. 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, et al. . The composite international diagnostic interview. An epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988;45:1069–77. 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. . The Mini-International neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59 Suppl 20:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beck AT, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961;4:561–5. 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parkitny L, McAuley J. The depression anxiety stress scale (DASS). J Physiother 2010;56:204 10.1016/S1836-9553(10)70030-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Islam FMA. Psychological distress and its association with socio-demographic factors in a rural district in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0212765 10.1371/journal.pone.0212765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. . Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:184–9. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kessler RC, ANDREWS G, COLPE LJ, et al. . Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 2002;32:959–76. 10.1017/S0033291702006074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bessaha ML. Factor structure of the Kessler psychological distress scale (K6) among emerging adults. Res Soc Work Pract 2017;27:616–24. 10.1177/1049731515594425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brooks RT, Beard J, Steel Z. Factor structure and interpretation of the K10. Psychol Assess 2006;18:62–70. 10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Uddin MN, Islam FMA, Al Mahmud A. Psychometric evaluation of an interview-administered version of the Kessler 10-item questionnaire (K10) for measuring psychological distress in rural Bangladesh. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022967–11. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andrews G, Peters L. The psychometric properties of the composite international diagnostic interview. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998;33:80–8. 10.1007/s001270050026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kessler R, Mroczek D. Final versions of our non-specific psychological distress scale. Memo dated March 1994;10:1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Slade T, Johnston A, Oakley Browne MA, et al. . 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: methods and key findings. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2009;43:594–605. 10.1080/00048670902970882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004;13:93–121. 10.1002/mpr.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10). Aust N Z J Public Health 2001;25:494–7. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Furukawa TA, KESSLER RC, SLADE T, et al. . The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian national survey of mental health and well-being. Psychol Med 2003;33:357–62. 10.1017/S0033291702006700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kessler RC, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2010;19:4–22. 10.1002/mpr.310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bank W. Bangladesh current population, 2016. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=BD [Accessed 16 Aug 2017].

- 27. World Bank World Development Indicators 2016 (English). World Development Indicators. 2016 Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Monawar Hosain GM, Chatterjee N, Ara N, et al. . Prevalence, pattern and determinants of mental disorders in rural Bangladesh. Public Health 2007;121:18–24. 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Islam MM, Ali M, Ferroni P, et al. . Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in an urban community in Bangladesh. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:353–7. 10.1016/S0163-8343(03)00067-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. . Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the world health surveys. Lancet 2007;370:851–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Uddin MN, Bhar S, Islam FMA. An assessment of awareness of mental health conditions and its association with socio-demographic characteristics: a cross-sectional study in a rural district in Bangladesh. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:562 10.1186/s12913-019-4385-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hossain MD, Ahmed HU, Chowdhury WA, et al. . Mental disorders in Bangladesh: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:1–8. 10.1186/s12888-014-0216-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Statistics, B.B.o Population & Housing Census 2011 (Zila Series & Community Series). Available: http://203.112.218.65:8008/WebTestApplication/userfiles/Image/PopCen2011/C_Narail.pdf [Accessed 1 Feb 2017].

- 34. Central Intelligence Agency Adult literacy rate in Bangladesh, 2015. Available: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/bg.html [Accessed 2 Jun 2017].

- 35. Ministry of Finance, T.P.R.o.B Socio-Economic indicators of Bangladesh, 2017. Available: https://mof.portal.gov.bd/site/page/28ba57f5-59ff-4426-970a-bf014242179e/Bangladesh-Economic-Review [Accessed 8 Jun 2017].

- 36. Smith AB, Rush R, Fallowfield LJ, et al. . Rasch fit statistics and sample size considerations for polytomous data. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:1–11. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Linacre JM. Sample size and item calibration stability, 7, p. 328, 1994. Available: www.rasch.org/rmt/rmt74m.htm [Accessed 24 Jan 2018].

- 38. Uddin MN, Bhar S, Al Mahmud A, et al. . Psychological distress and quality of life: rationale and protocol of a prospective cohort study in a rural district in Bangladesh. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016745–10. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lindhiem O, Bennett CB, Rosen D, et al. . Mobile technology boosts the effectiveness of psychotherapy and behavioral interventions: a meta-analysis. Behav Modif 2015;39:785–804. 10.1177/0145445515595198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goodspeed R, Yan X, Hardy J, et al. . Comparing the data quality of global positioning system devices and mobile phones for assessing relationships between place, mobility, and health: field study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2018;6:e168 10.2196/mhealth.9771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Deussom RH, Mitchell M, Ruben JD. Using Mobile Technology to Address the ‘Three Delays' to Reduce Maternal Mortality in Zanzibar, in E-Health and Telemedicine: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications. IGI Global, 2016: 1140–54. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Svoronos T, et al. CommCare: automated quality improvement to strengthen community-based health. Weston: D-Tree International, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bogan M. Improving standards of care with mobile applications in Tanzania. in W3C Workshop on the Role of Mobile Technologies in Fostering Social and Economic Development in Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44. DIMAGI CommCare, 2018. Available: https://www.dimagi.com/commcare/ [Accessed 25 May 2018].

- 45. Rasch G. An item analysis which takes individual differences into account. Br J Math Stat Psychol 1966;19:49–57. 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1966.tb00354.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Andrich D. A rating formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika 1978;43:561–73. 10.1007/BF02293814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Andrich D, Sheridan B, Luo G. Rasch models for measurement: RUMM2030. Perth, Western Australia: RUMM Laboratory Pty Ltd, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pallant JF, Tennant A. An introduction to the Rasch measurement model: an example using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). British Journal of Clinical Psychology 2007;46:1–18. 10.1348/014466506X96931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. RUMM2030 RUMM2030 for analysing assessment and attitude questionnaire data, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tennant A, Conaghan PG. The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology: what is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a Rasch paper? 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gerbing DW, Anderson JC. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research 1988;25:186–92. 10.1177/002224378802500207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Engelhard G. Rasch models for measurement—Andrich D. Applied Psychological Measurement 1988;12:435–6. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Leon AC. Multiplicity-adjusted sample size requirements: a strategy to maintain statistical power with Bonferroni adjustments. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:1511–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bland JM, Altman DG. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ 1995;310:170 10.1136/bmj.310.6973.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kowalski A, Enck P. Statistical methods: multiple significance tests and the Bonferroni procedure. Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie 2010;60:286–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pomeroy IM, Tennant A, Young CA. Rasch analysis of the WHOQOL-BREF in post polio syndrome. J Rehabil Med 2013;45:873–80. 10.2340/16501977-1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bond TG, Fox CM. Applying the Rasch model: fundamental measurement in the human sciences. 2nd ed Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2007: 340. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Linacre JM. Optimizing rating scale category effectiveness. J Appl Meas 2002;3:85–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brentani E, Golia S. Unidimensionality in the Rasch model: how to detect and interpret. Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends 2007;67:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tennant A, Pallant JF. DIF matters: a practical approach to test if differential item functioning makes a difference. Rasch Measurement Transactions 2007;24:1082–4. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Smith RM. Fit analysis in latent trait measurement models. J Appl Meas 2000;1:199–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Andrich D, et al. RUMM: a Windows-based item analysis program employing Rasch unidimensional measurement models. Perth, Australia: Murdoch University, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Romanoski J, Douglas G, scores T. Test scores, measurement, and the use of analysis of variance: an historical overview. J Appl Meas 2002;3:232–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Anderson TM, Sunderland M, Andrews G, et al. . The 10-Item Kessler psychological distress scale (K10) as a screening instrument in older individuals. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2013;21:596–606. 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Oakley Browne MA, Wells JE, Scott KM, et al. . The Kessler psychological distress scale in Te Rau Hinengaro: the New Zealand mental health survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010;44:314–22. 10.3109/00048670903279820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fassaert T, De Wit MAS, Tuinebreijer WC, et al. . Psychometric properties of an interviewer-administered version of the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10) among Dutch, Moroccan and Turkish respondents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2009;18:159–68. 10.1002/mpr.288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Nguyen L, et al. Psychological distress measured using the Kessler scale (K6) predicts long-term postoperative pain after wrist surgery. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia-Journal Canadien D Anesthesie 2012;59:1150–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mitchell CM, Beals J. The utility of the Kessler screening scale for psychological distress (K6) in two American Indian communities. Psychol Assess 2011;23:752–61. 10.1037/a0023288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, et al. . The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2008;17:152–8. 10.1002/mpr.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Easton SD, Safadi NS, Wang Y, et al. . The Kessler psychological distress scale: translation and validation of an Arabic version. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15 10.1186/s12955-017-0783-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bu X-qing, You L-ming, Li Y, et al. . Psychometric properties of the Kessler 10 scale in Chinese parents of children with cancer. Cancer Nurs 2017;40:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Eaton NR, Keyes KM, Krueger RF, et al. . An invariant dimensional liability model of gender differences in mental disorder prevalence: evidence from a national sample. J Abnorm Psychol 2012;121:282–8. 10.1037/a0024780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Baillie AJ. Predictive gender and education bias in Kessler's psychological distress scale (K10). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2005;40:743–8. 10.1007/s00127-005-0935-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Plaisier I, de Bruijn JGM, Smit JH, et al. . Work and family roles and the association with depressive and anxiety disorders: differences between men and women. J Affect Disord 2008;105:63–72. 10.1016/j.jad.2007.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Miech R, Power C, Eaton WW. Disparities in psychological distress across education and sex: a longitudinal analysis of their persistence within a cohort over 19 years. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:289–95. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Andrews G, Henderson S, Hall W. Prevalence, comorbidity, disability and service utilisation. Overview of the Australian National Mental Health Survey. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:145–53. 10.1192/bjp.178.2.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Pratt LA, Dey AN, Cohen AJ. Characteristics of adults with serious psychological distress as measured by the K6 scale, United States, 2001–04. United States 2007:2001–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Fushimi M, Saito S, Shimizu T, et al. . Prevalence of psychological distress, as measured by the Kessler 6 (K6), and related factors in Japanese employees. Community Ment Health J 2012;48:328–35. 10.1007/s10597-011-9416-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kessler RC, Foster C, Webster PS, et al. . The relationship between age and depressive symptoms in two national surveys. Psychol Aging 1992;7:119–26. 10.1037/0882-7974.7.1.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Newmann JP. Aging and depression. Psychol Aging 1989;4:150–65. 10.1037/0882-7974.4.2.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Roberts RE. Reliability of the CES-D scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Res 1980;2:125–34. 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Uddin MN, Islam FMA. Psychometric evaluation of an interview-administered version of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire for use in a cross-sectional study of a rural district in Bangladesh: an application of Rasch analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:216 10.1186/s12913-019-4026-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kessler RC. A disaggregation of the relationship between socioeconomic status and psychological distress. Am Sociol Rev 1982;47:752–64. 10.2307/2095211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kosidou K, Dalman C, Lundberg M, et al. . Socioeconomic status and risk of psychological distress and depression in the Stockholm public health cohort: a population-based study. J Affect Disord 2011;134:160–7. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Smith AB, Rush R, Fallowfield LJ, et al. . Rasch fit statistics and sample size considerations for polytomous data. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:33 10.1186/1471-2288-8-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Andrich D. Understanding the response structure and process in the polytomous Rasch model. Handbook of Polytomous Item Response Theory Models 2010:123–52. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Andrich D, Marais I. A course in Rasch measurement theory: measuring in the educational, social and health sciences. Springer, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-034523supp001.pdf (11.8KB, pdf)