Abstract

Introduction

Management of inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) remains a clinical challenge. Currently, medical treatment involving pulmonary vasodilators (such as soluble guanylate-cyclase stimulators) is recommended, primarily for ameliorating symptoms. More recently, balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) has been developed as alternative treatment for inoperable CTEPH. This study aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of BPA and riociguat (a soluble guanylate-cyclase stimulator) as treatments for inoperable CTEPH.

Methods and analysis

This study is a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Subjects with inoperable CTEPH were randomised (1:1) into either a BPA or riociguat group, and observed for 12 months after initiation of treatment. The primary endpoint will be the change in mean pulmonary arterial pressure from baseline to 12 months after initiation of treatment. For primary analysis, we will estimate the least square means difference and 95% CI for the change of pulmonary arterial pressure between the groups at 12 months using the analysis of covariance adjusted for allocation factors.

Ethics and dissemination

This study and its protocols were approved by the institutional review board of Keio University School of Medicine and each participating institution. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Results will be disseminated at medical conferences and in journal publications.

Trial registration number

University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trial Registry (UMIN000019549); Pre-results.

Keywords: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, balloon pulmonary angioplasty, riociguat

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a randomised controlled trial comparing the efficacy and safety of balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) and riociguat in patients with inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

This study evaluates the efficacy and safety of BPA and riociguat over a relatively longer period (12 months).

This is the first study to compare health insurance resource costs between BPA and riociguat.

A limitation of this study is the open-label trial design.

Another limitation of this study is that a relatively small number of subjects were recruited.

Introduction

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is characterized by stenosis and/or occlusion of pulmonary arteries caused by organised thrombi.1 Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are critical, as the condition is associated with a high rate of mortality due to right-sided heart failure.2 Pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA) is an established curative treatment for operable CTEPH.3 4 According to the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology,5 European Society of Cardiology/European Respiratory Society (ESC/ERS)6 and Japanese Circulation Society/the Japanese Pulmonary Circulation and Pulmonary Hypertension Society (JCS/JPCPHS)7 guidelines, PEA is recommended for patients with operable CTEPH as the first-line therapy in the case of recommendation class I and level of evidence C.

In 2014, for the first time, a soluble guanylate-cyclase stimulator (riociguat, a pulmonary vasodilator) received approval for insurance reimbursement in the context of inoperable or persistent/recurrent CTEPH. This was based on the findings of a multicentre randomised clinical trial (CHEST-1)8 and its extension study (CHEST-2),9 which highlighted the efficacy of riociguat for patients with inoperable CTEPH. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) is a catheter-based treatment, which has also been reported to be effective for inoperable CTEPH.10–22 Riociguat and BPA are recommended for patients with inoperable CTEPH in the case of recommendation class I and level of evidence B, or recommendation class IIb and level of evidence C, respectively, in the 2015 ESC/ESR guidelines,6 and in the case of recommendation class I and level of evidence B, and recommendation class I and level of evidence C, respectively, in the 2017 JCS/JPCPHS guidelines.7 Although BPA is associated with the risk of complications such as procedure-related pulmonary artery injury, it can result in marked improvement of CTEPH. Riociguat is an effective pulmonary vasodilator and is associated with a low risk of serious adverse events. It has been reported that sequential treatment with riociguat and BPA results in significant improvements in terms of mean pulmonary arterial pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance among patients with inoperable CTEPH,23 no reports to date have directly compared the treatment outcomes of these two treatment methods. A randomised controlled trial comparing riociguat and BPA (the RACE study) is conducted in France,24 aligning with the start of this study.25 The aim of this study is to compare the efficacy and safety of riociguat and BPA for inoperable CTEPH over the course of 12 months. The results of this study may aid in optimising treatment selection and improving patient outcomes.

Methods and analysis

Study design and setting

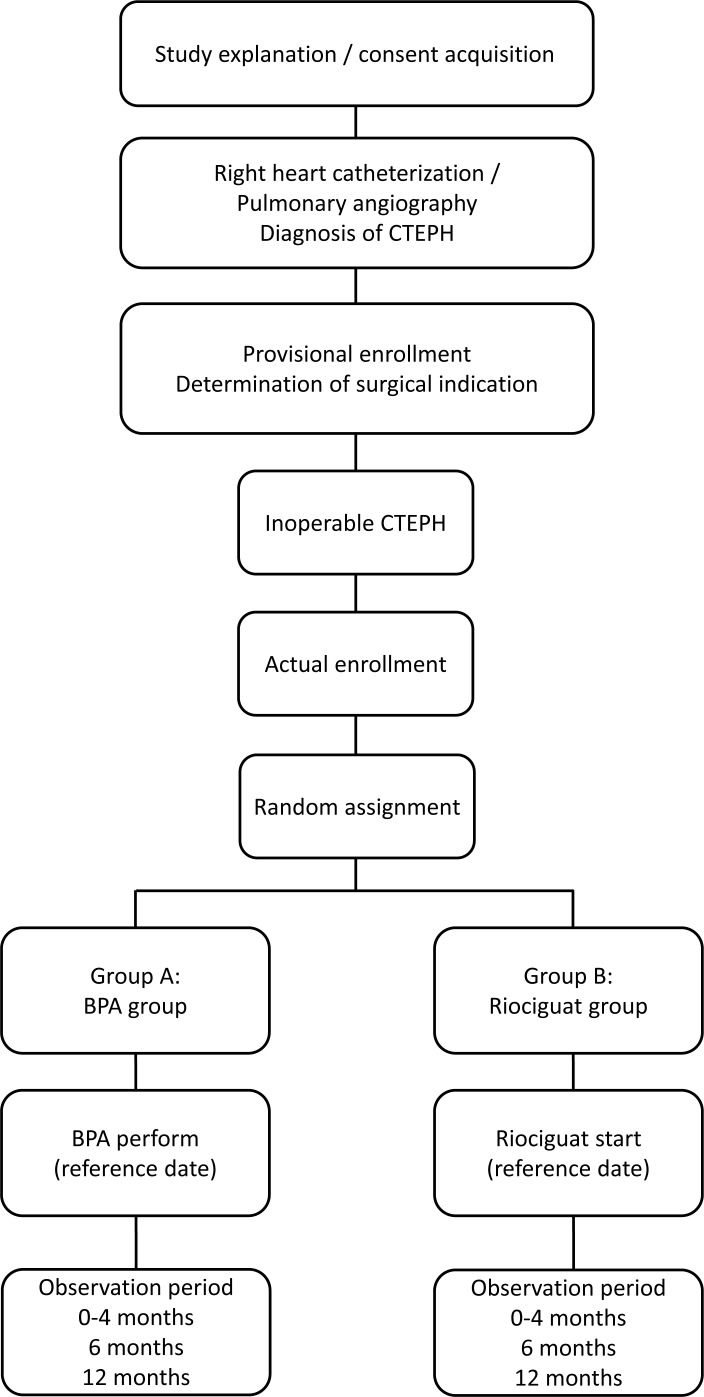

This multicentre randomised controlled trial based on BPA for CTEPH (MR BPA) study recruited subjects from 15 January 2016 to 31 October 2019. This study is a multicentre, prospective, randomised controlled trial. As shown in figure 1, subjects willing to consider enrollment were consented prior to invasive evaluation. Subjects underwent right-heart catheterization and pulmonary angiography for definitive diagnosis of CTEPH by the standard practice in Japan. The identified CTEPH patients were provisionally enrolled in this study. An independent experienced PEA surgeon determined if subjects were eligible for PEA. If the subjects were deemed technically operable, they were excluded from this study. Those who were judged to have inoperable CTEPH were assigned into either a BPA or riociguat group via an online assignment system, and will be observed for 12 months. In the BPA group, the severity of pulmonary hypertension and morphology of the pulmonary lesion were evaluated by preoperative right-heart catheterization and pulmonary angiography. Then, BPA will be conducted depending on the lesion type. If lesions of pulmonary artery are not suitable for BPA, the procedure will not be performed even if the patient is assigned to the BPA group. However, at least among the collaborative institutions included in this study, PEA-inoperable patients are very rarely considered unsuitable for BPA, because these institutes are expert BPA centres in Japan. In general, BPA will be completed within 4 months of the first BPA procedure. In the riociguat group, 1.0 mg riociguat will be administered three times per day. When systolic blood pressure is 95 mm Hg or higher, the dose will be increased by 0.5 mg every 2 weeks up to a maximum dosage of 2.5 mg three times per day. Dosage adjustment will be completed within 4 months of the first administration of riociguat, and administration will be continued for a total of 12 months. Observations will be made at the time of screening; at baseline and at 0–4, 6 and 12 months after initial treatment. Table 1 shows the schedule of assessments performed at each visit for each treatment group, including mandatory and optional assessments.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study recruitment and randomisation. After obtaining consent and diagnosis of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is confirmed, subjects will be randomised into either the balloon pulmonary angioplasty or riociguat group, to receive treatment for 12 months. Observations will be recorded at the time of screening; at baseline and at 0–4, 6 and 12 months after the initiation of treatment. BPA, balloon pulmonary angioplasty; CTEPH, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

Table 1.

Schedule of assessments for enrolled subjects

| Observation items | Screening | Baseline | Observation period | ||

| ~0 month | 0 month | 0–4 months | 6 months+1 month | 12 months+2 months | |

| Subjects’ attributes | 〇 | 〇 | — | — | — |

| 6 min walk distance | — | 〇 | — | 〇 | 〇 |

| Borg dyspnea index | — | 〇 | — | 〇 | 〇 |

| WHO functional class | — | 〇 | — | 〇 | 〇 |

| Right-heart catheterization | 〇 | — | — | 〇 | 〇 |

| Pulmonary angiography | 〇 | — | — | — | — |

| Pulmonary function | — | 〇 | — | 〇 | 〇 |

| Blood gas test* | 〇 | — | 〇 | 〇 | |

| Vital signs* | 〇 | — | 〇 | 〇 | |

| Echocardiography (cardiac ultrasound) | — | 〇 | — | 〇 | 〇 |

| Chest X-ray | 〇 | 〇† | 〇 | 〇 | |

| Chest CT scan | 〇 | — | 〇† | 〇 | 〇 |

| Oxygen therapy usage status | — | 〇 | — | 〇 | 〇 |

| Adverse event onset‡ | — | — | ← 〇 → | ||

| Clinical worsening and time to clinical worsening‡ | — | — | ← 〇 → | ||

| Quality-of-life parameters (EQ5D) | — | 〇 | — | 〇 | 〇 |

| Health insurance | — | — | ← 〇 → | ||

| BPA status§ | — | — | 〇 | ― | ― |

| Medication adherence¶ | — | — | ← 〇 → | ||

*Recommended during right-heart catheterization.

†Required if BPA is performed.

‡Onset of adverse events and indices related to clinical worsening will be observed as necessary throughout the clinical study period.

§Observational items for the BPA group.

¶Observational items for the riociguat group.

BPA, balloon pulmonary angioplasty.

Sample size calculation

Previously, BPA has been shown to result in reduced mean pulmonary arterial pressure from 45.4±9.6 to 24.0±6.4 mm Hg (mean±SD) within 24 months,11 while riociguat has been reported to decrease pulmonary arterial pressure by 4±7 mm Hg.9 Based on these studies, it was assumed that the change in mean pulmonary arterial pressure from the start of treatment to 12 months after treatment would be −15 mm Hg for the BPA group and −4 mm Hg for the riociguat group, with SD of 14 and 10, respectively. The minimum sample size required to achieve a significance of 0.05 from a two-sided test with a statistical power of 90% was determined to be 27 subjects for both groups, a total of 54 subjects. We estimated the dropout rate to be 10%; thus, the planned enrollment was set at 60 subjects, with 30 in each group.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria: (a) Diagnosis with CTEPH with a WHO functional class II or III based on the diagnostic criteria of the 2012 Japanese Circulation Society guidelines,24 (b) age ≥ 20 or <80 years, (c) mean pulmonary arterial pressure of ≥25 to <60 mm Hg and pulmonary artery wedge pressure of ≤15 mm Hg, (d) administration of appropriate anticoagulant therapy for at least 3 months prior to study enrollment (in the case of warfarin, the prothrombin time–international normalised ratio should be 1.5–3.0) and (e) provision of written informed consent to participate after full explanation of this study.

Exclusion criteria: (a) History of BPA, (b) PEA within 6 months prior to study enrollment, (c) use of unapproved pharmaceutical products, (d) use of a pulmonary vasodilator within 4 weeks prior to right-heart catheterization, (e) co-existing aetiology of pulmonary hypertension, (f) pregnancy or breastfeeding, (g) contraindicated for riociguat, (h) life expectancy of less than 2 years and (i) deemed to be unsuitable for participation by the investigators.

Recruitment and consent

The informed consent document was presented to potentially eligible subjects to provide a comprehensive explanation of this study. Written consent was then obtained.

As a general rule, subjects willing to consider enrollment were consented prior to right-heart catheterization and pulmonary angiography for definitive diagnosis of CTEPH by the standard practice in Japan. However, to reduce the burden on the subjects, suitable patients that had undergone comprehensive evaluation, including right-heart catheterization and pulmonary angiography, within 3 months prior to the consenting could also be enrolled to this study. This was explained to subjects by investigators at the time of obtaining consent.

Once consent was obtained, an independent experienced PEA surgeon who is not involved in this study determined operability (whether subjects were eligible for PEA) based on imaging data according to the Guidelines for Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension (2012 revised version).26

Random allocation

Random assignment were performed centrally with stratification by mean pulmonary arterial pressure (<40 and ≥40 mm Hg), and research institutions (Keio University, Okayama Medical Center, Kyusyu University and Kobe University) by biased-coin minimisation.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint will be the change in mean pulmonary arterial pressure between baseline and 12 months. Secondary endpoints will include several clinical and quality-of-life parameters (as detailed in table 2).

Table 2.

Secondary endpoints that will be measured and/or compared at baseline and at 12 months after initiation of treatment

| Endpoint | |

| Change in 6 min walk distance | |

| Change in Borg dyspnea index | |

| Change in haemodynamic variables | Including pulmonary vascular resistance, mean right arterial pressure, cardiac output, etc. |

| Change in WHO functional class | |

| Change in plasma brain natriuretic peptide levels | |

| Change in SaO2 and PaO2 | |

| Change in usage volume of oxygen therapy | Including commencing oxygen therapy due to exacerbation of primary disease or dosage change. |

| Change in pulmonary function | |

| Change in echocardiography parameter | |

| Frequency and severity of pulmonary artery injury | Assessed by chest X-ray and chest CT scan. |

| Frequency of adverse events | Bloody sputum/hemoptysis/pulmonary haemorrhage (vascular perforation, vascular dissection, vascular rupture, etc), pneumothorax, hypotension, pulmonary congestion/pulmonary oedema, late-onset lung disturbance, heart failure, pneumonia, headache, dizziness, peripheral oedema, nausea/vomiting, retching, diarrhoea, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory inflammation, respiratory distress, coughing and fainting. |

| Clinical worsening during the observation period and time to clinical worsening | All-cause mortality, heart/lung transplant, salvage PEA due to worsening of primary disease, new or repeated implementation of BPA due to the worsening of a primary disease, hospitalisation, new initiation of pulmonary vasodilators, worsening of 30% or greater from baseline in the 6 min walk distance and persistent worsening in the WHO functional class from baseline due to the worsening of a primary disease. |

| Change in quality-of-life parameters (EQ5D) | |

| Health insurance resource costs |

BPA, balloon pulmonary angioplasty; PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen; PEA, pulmonary endarterectomy; SaO2, saturation of arterial blood.

Data collection

An electronic, clinical-test data collection system—electric data capture (EDC) system—is used for data collection. In cases when the system is unavailable, a case report form—a specialised data collection form—is used, and the data were later entered into the EDC. The investigators who enter information into the EDC system are responsible for ensuring accuracy and completeness of information. The information of the health insurance resource costs are collected from diagnosis procedure combination/pre-diem payment system.

Data management and monitoring

Data collection and management are carried out by third-party entities to avoid bias. The data management is performed by Soiken Inc. Data Management Group (the Data Centre). The Data Centre prepared a ‘Procedure Manual for Data Management’. The Data Centre’s approval is required prior to sending any data related to the subjects in an electronic format. If data are transmitted over an unsecured electronic network, the data must be encoded at the source. Linkable anonymisation by central registration number is used to identify the subjects. The investigators are responsible for appropriate storage of the correspondence table prepared by them to identify the subjects, in accordance with the procedures at the particular research institution. This correspondence table must be retained for 5 years after completion of this study. Appropriate measures, such as encoding or deletion, are taken to ensure that the subjects cannot be identified in any display or public disclosure of information related to this study, in accordance with applicable laws and regulations.

The Data Centre monitors this study to manage and ensure quality. The monitoring manager monitors the subjects in accordance with the manual on monitoring procedure. For data quality management, the principal investigator and Central Committee confirms the progress of this study as necessary through the Data Centre to ensure conformance with the protocol and the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects (22 December 2014; Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology/Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) and the Clinical Trials Act (14 April 2017; Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology/Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare).

Adverse events

The occurrence of any untoward medical events, including complications or the worsening of pre-existing underlying diseases, is defined as adverse events. Worsening of efficacy evaluation indices is defined as adverse events. Any concomitant symptoms or clinically significant abnormal fluctuations in test results are investigated to determine whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship with BPA or riociguat, and findings will be documented in the EDC system. Adverse events are followed up until normalisation or recovery to a level not considered to be an adverse event, or, in the case of an irreversible adverse event (cerebral infarction, myocardial infarction, etc), until symptoms stabilise.

Statistical analysis

Primary and secondary efficacy endpoints will be analysed using the full study population, which will include all patients who were randomised into one of the intervention groups. However, patients who withdraw their consent, patients with severe protocol violation, such as registration without consenting, or registration out of the enrollment period, or patients without any data related to the primary endpoint after the randomisation were excluded from the full study population. The safety analysis will be conducted in the safety analysis population, which will include all patients who were randomised into one of the intervention groups and either received at least one dose of riociguat or attended at least one BPA procedure (regardless of whether BPA was carried out or not).

Baseline variables are presented as frequencies and proportions for categorical data, and means and SD for the continuous data. Patient characteristics will be compared using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical endpoints, and the Student’s t-test for continuous variables.

For primary analysis, the least square means difference and 95% CI for change of pulmonary arterial pressure between groups at 12 months will be estimated using analysis of covariance adjusted for allocation factors. Secondary analysis will be performed in the same manner as primary analysis. Adverse events will be evaluated during the safety analysis. The frequencies of adverse events will be compared using Fisher’s exact test. All comparisons are planned, and all p values will be two sided. We consider p values of <0.05 to be statistically significant. All statistical analysis will be performed using SAS software V.9.4 (SAS Institute). Statistical analysis plan will be developed by the principal investigator and biostatistician before completion of patient recruitment and data fixation.

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor public are involved in this study, including the planning, execution, analysis and evaluation.

Discussion

Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment for CTEPH in Western countries5 6 and Japan7 26 recommend riociguat and BPA for patients with inoperable CTEPH. However, there are no reports directly comparing treatment outcomes of these two approaches. The primary endpoint of this study will be the change in mean pulmonary arterial pressure from baseline to 12 months, as this is an important prognostic factor of CTEPH. Other outcomes often used in studies on CTEPH, such as the 6 min walk distance and pulmonary vascular resistance, are secondary endpoints in this study. Sequential treatment with riociguat and BPA for patients with inoperable CTEPH has been shown to significantly improve mean pulmonary arterial pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance, highlighting the benefits of BPA.23 A randomised controlled trial directly comparing riociguat and BPA is conducted in France24; this study was, therefore, planned to compare the efficacy and safety of riociguat and BPA for treatment of inoperable CTEPH. This study and the RACE study both began in January 2016.25 Results from randomised trials such as these will be critical for optimising treatment selection and improving outcomes of inoperable CTEPH.

In this study, BPA treatment will be completed in 4 months, which is equivalent as real-world conditions in Japan. This study will also evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of riociguat and BPA by continuing evaluations for 12 months after initiation of treatment. A recent systematic review has shown that treatment outcomes of BPA are better in Japan than in Western countries.4 27 This study is conducted in expert CTEPH centres in Japan, and will, therefore, compare the treatment efficacy and safety of riociguat and the highest quality BPA in Japan. In addition, the operability of PEA was determined by an independent experienced PEA surgeon who belongs to independent institute and is the most experienced PEA surgeon in Japan, having performed 49 PEAs in the last 3 years (320 PEAs in total). This avoided recruitment bias and guarantee reliability in this study. Furthermore, this study will compare the costs to health insurance resources and patient-reported quality-of-life parameters for each therapy. These factors may contribute to optimising treatment strategies or amending treatment guidelines for inoperable CTEPH. While these are the strengths of this study, there are several limitations, which should be acknowledged. One limitation is that this is an open-label trial. Because there is no distinct criterion for BPA in each lesion, operators are aware of the mean pulmonary arterial pressure (the primary endpoint in this study), and they might be incentivised to continue BPA. Thus, bias for the BPA operators cannot be completely avoided. However, since this study will compare medical and surgical treatment, it is difficult to use a placebo or mask patients and/or physicians. Another limitation is that a relatively small number of patients will be enrolled (30 subjects per group, a total of 60 subjects).

Ethics and dissemination

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after full explanation of this study. The results of this study will be disseminated at medical conferences and in journal publications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Bayer Yakuhin Ltd.

Footnotes

TK and HM contributed equally.

Contributors: TK and HM contributed to the conception and design of the study, drafted the protocol and supervised the revision. MK, KA, SK, YS and TS provided intellectual input to improve the study design and revise the protocol. KF contributed to and supervised the conception and design of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was financially supported by Bayer Yakuhin Ltd. Bayer Yakuhin Ltd. is not involved in this study, including the planning, execution, data management, statistical analysis, evaluation or write-up.

Competing interests: SK received honoraria for scientific lectures from Bayer Yakuhin Ltd. KF received scholarship grants from Bayer Yakuhin Ltd. and MSD K.K.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study and its protocols were first approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution: Keio University School of Medicine an Ethical Committee, Ethics Committee of Okayama Medical Center, Clinical trial ethical review committee of Kyusyu University Graduated School of Medicine and Medical Ethical committee of Kobe University Graduated School of Medicine, according to the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects issued by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan. Because of the dispense of the Clinical Trials Act in April 2017, this study and its protocols were again inspected and approved by the Certified Review Board of Keio, which had obtained certification from the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan. This study is conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects issued by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan, the Clinical Trials Act and other current legal regulations in Japan.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Memon HA, Lin CH, Guha A. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: pearls and pitfalls of diagnosis. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J 2016;12:199–204. 10.14797/mdcj-12-4-199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nishimura R, Tanabe N, Sugiura T, et al. . Improved survival in medically treated chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circ J 2013;77:2110–7. 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Madani MM. Surgical treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J 2016;12:213–8. 10.14797/mdcj-12-4-213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim NH, Delcroix M, Jais X, et al. . Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2019;53:1801915 10.1183/13993003.01915-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et al. . ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: a report of the American College of cardiology Foundation Task force on expert consensus documents and the American heart association: developed in collaboration with the American College of chest physicians, American thoracic Society, Inc., and the pulmonary hypertension association. Circulation 2009;119:2250–94. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery J-L, et al. . 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the joint Task force for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension of the European Society of cardiology (ESC) and the European respiratory Society (ERS): endorsed by: association for European paediatric and congenital cardiology (AEPC), International Society for heart and lung transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 2016;37:67–119. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fukuda K, Date H, Doi S, et al. . Guidelines for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension (JCS 2017/JPCPHS 2017). Circ J 2019;83:842–945. 10.1253/circj.CJ-66-0158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ghofrani H-A, D'Armini AM, Grimminger F, et al. . Riociguat for the treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med 2013;369:319–29. 10.1056/NEJMoa1209657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simonneau G, D'Armini AM, Ghofrani H-A, et al. . Riociguat for the treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a long-term extension study (CHEST-2). Eur Respir J 2015;45:1293–302. 10.1183/09031936.00087114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kataoka M, Inami T, Hayashida K, et al. . Percutaneous transluminal pulmonary angioplasty for the treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5:756–62. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.971390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mizoguchi H, Ogawa A, Munemasa M, et al. . Refined balloon pulmonary angioplasty for inoperable patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5:748–55. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.971077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Andreassen AK, Ragnarsson A, Gude E, et al. . Balloon pulmonary angioplasty in patients with inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Heart 2013;99:1415–20. 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fukui S, Ogo T, Morita Y, et al. . Right ventricular reverse remodelling after balloon pulmonary angioplasty. Eur Respir J 2014;43:1394–402. 10.1183/09031936.00012914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taniguchi Y, Miyagawa K, Nakayama K, et al. . Balloon pulmonary angioplasty: an additional treatment option to improve the prognosis of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. EuroIntervention 2014;10:518–25. 10.4244/EIJV10I4A89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tsugu T, Murata M, Kawakami T, et al. . Significance of echocardiographic assessment for right ventricular function after balloon pulmonary angioplasty in patients with chronic thromboembolic induced pulmonary hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2015;115:256–61. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dimopoulos K, Kempny A, Alonso-Gonzalez R, et al. . Percutaneous transluminal pulmonary angioplasty for the treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: challenges and future directions. Int J Cardiol 2015;187:401–3. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ogawa A, Satoh T, Fukuda T, et al. . Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: results of a multicenter registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017;10:e004029 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kimura M, Kohno T, Kawakami T, et al. . Midterm effect of balloon pulmonary angioplasty on hemodynamics and subclinical myocardial damage in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2017;33:463–70. 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aoki T, Sugimura K, Tatebe S, et al. . Comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of balloon pulmonary angioplasty for inoperable chronic thrombo-embolic pulmonary hypertension: long-term effects and procedure-related complications. Eur Heart J 2017;38:3152–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Olsson KM, Wiedenroth CB, Kamp J-C, et al. . Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for inoperable patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: the initial German experience. Eur Respir J 2017;49:1602409 10.1183/13993003.02409-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kawakami T, Ogawa A, Miyaji K, et al. . Novel angiographic classification of each vascular lesion in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension based on selective angiogram and results of balloon pulmonary angioplasty. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2016;9:e003318 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ogo T, Fukuda T, Tsuji A, et al. . Efficacy and safety of balloon pulmonary angioplasty for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension guided by cone-beam computed tomography and electrocardiogram-gated area detector computed tomography. Eur J Radiol 2017;89:270–6. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wiedenroth CB, Ghofrani HA, Adameit MSD, et al. . Sequential treatment with riociguat and balloon pulmonary angioplasty for patients with inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ 2018;8:2045894018783996 10.1177/2045894018783996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Riociguat versus balloon pulmonary Angioplasty in non-operable Chronic thromboEmbolic pulmonary hypertension (RACE) Clinicaltrials.Gov identifier NCT02634203. Available: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02634203 [Accessed 21 May 2019].

- 25. Multicenter Randomized controlled trial based on Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (MR BPA study) UMIN-CTR ID: UMIN000019549. Available: https://upload.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000022608 [Accessed 21 May 2019].

- 26. Nakanishi N, Ando M, Ueda H, et al. . Guidelines for treatment of pulmonary hypertension (JCS2012), 2012. Available: http://www.j-circ.or.jp/guideline/pdf/JCS2012_nakanishi_h.pdf [Accessed 5 Sep 2018].

- 27. Tanabe N, Kawakami T, Satoh T, et al. . Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a systematic review. Respir Investig 2018;56:332–41. 10.1016/j.resinv.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.