Abstract

Introduction

Early breast cancer detection and advancements in treatment options have resulted in an increase of breast cancer survivors. An increasing number of women are living with the long-term effects of breast cancer treatment, making the quality of survivorship an increasingly important goal. Breast cancer-related lymphoedema (BCRL) is one of the most underestimated complications of breast cancer treatment with a reported incidence of 20%. A microsurgical technique called lymphaticovenous anastomosis (LVA) might be a promising treatment modality for patients with BCRL. The main objective is to assess whether LVA is more effective than the current standard therapy (conservative treatment) in terms of improvement in quality of life and weather it is cost-effective.

Methods and analysis

A multicentre, randomised controlled trial, carried out in two academic and two community hospitals in the Netherlands. The study population includes 120 women over the age of 18 who have undergone treatment for breast cancer including axillary treatment (sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary lymph node dissection) and/or axillary radiotherapy, presenting with an early stage lymphoedema of the arm, viable lymphatic vessels and received at least 3 months conservative treatment. Sixty participants will undergo the LVA operation and the other sixty will continue their regular conservative treatment, both with a follow-up of 24 months. The primary outcome is the health-related quality of life. Secondary outcomes are societal costs, quality adjusted life years, cost-effectiveness ratio, discontinuation rate of conservative treatment and excess limb volume.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Maastricht University Medical Center (METC) on 19 December 2018 (NL67059.068.18). The results of this study will be disseminated in presentations at academic conferences, publications in peer-reviewed journals and other news media.

Trial registration number

NCT02790021; Pre-results.

Keywords: plastic & reconstructive surgery, breast surgery, plastic & reconstructive surgery

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This multicentre randomised controlled trial compares the lymphaticovenous anastomosis operation with conservative therapy (the standard care) in patients with breast cancer-related lymphoedema.

Effectiveness of lymphaticovenous anastomosis is examined in terms of patient-relevant, clinical and economic outcomes; health-related quality of life, excess limb volume, discontinuation rate of conservative treatment, societal costs and cost-effectiveness.

This study contains digital questionnaires and a patient diary with automatic warnings in case of blank answers to minimise missing data.

Blinding of patients or researcher is not possible in this study due to visible scars postoperatively.

Cost-effectiveness analysis may not be generalisable to other countries.

Introduction

An increasing number of women survive breast cancer due to advancements in treatment options. As a result, the number of women living with the long-term effects of breast cancer treatment grows, making the quality of survivorship more relevant. Between 8% and 56% of breast cancer survivors develop arm or shoulder problems such as restricted shoulder mobility, shoulder pain and lymphoedema,1–6 with one of the most underestimated and debilitating morbidities of them all being upper limb lymphoedema.

Up to 70% of the patients who develop breast cancer-related lymphoedema (BCRL) do so within the first 2 years post-treatment, however, cases have been described of women developing upper limb lymphoedema 20 years or later after initial treatment.7–13 In the Netherlands, between 7% and 30% of the 14 000 annual patients with invasive breast cancer will develop lymphoedema depending on certain treatment and patient related risk factors.14 15

The following risk factors are associated with the development (and severity) of BCRL: the extent of breast/axillary surgery, adjuvant radiation, (neo-)adjuvant chemotherapy, the number of positive nodes, treatment in dominant limb and obesity.5 16–20 Limb swelling may present with symptoms of heaviness, tightness, pain and loss of normal arm function and range of motion. The negative psychological effects brought on by the impairments of activities in daily life and reduced limb aesthetics constitute an additional burden and decrease in health-related quality of life (HRQoL).1 7 11 13 21 Moreover, infections of the skin are regularly seen in a severe stadium of lymphoedema, such as erysipelas or cellulitis.2 8 21

Conservative therapy

Complex decongestive therapy (CDT), currently accepted as the standard treatment for lymphoedema, is initially aimed at alleviating symptoms without curative intent which for most patients means lifelong treatment and a constant reminder of the breast cancer period. CDT includes general skin care, patient education, compression therapy with compression bandages and garment, manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) and exercise therapy.14 22 23 A systematic review concluded that compression garment in combination with manual lymph drainage induces a significant limb volume reduction of 17% to 60%.24 Another randomised controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated a 29% reduction in excess limb volume with combined conservative therapy.25 However, after reaching maximum limb volume reduction, compression garment are lifelong necessary for the patients to maintain the volume reduction obtained.

Lymphaticovenous anastomosis

Connections can be made between the lymphatic and venous systems to divert static lymph fluid away from the obstruction site in a technique called lymphaticovenous anastomosis (LVA).26 Due to advancements, microvascular surgery is more developed, and anastomoses in vessels as small as 0.3 mm in diameter are made possible.

Several studies on lymphatic super microsurgery performing LVA are available.26–41 Most of the studies describe results on both upper and lower limb lymphoedema and not only secondary lymphoedema.27 34 Nevertheless, studies mention a volume or circumference decrease between 30% and 61%, and positive results on subjective complaints with low incidence or no complications.26–29 31 36–39 41 Furthermore, more than half of the patients eventually were able to discontinue compression garment after an LVA procedure.27 42

Many studies have been performed, mostly reporting on a small study population. Furthermore, the majority were retrospective, few were prospective, yet none of them were randomised. Another disadvantage is the heterogeneity of the patient population, assessment modalities and inconsistent reporting of outcomes and complications.27 30 34

The aim of this multicentre RCT is to examine HRQoL and (cost-)effectiveness of LVA compared to CDT in a large homogenous group of patients with BCRL.

Methods and analysis

Study design

The LYMPH trial is a multicentre, non-blinded, RCT and will be conducted in the Maastricht University Medical Center, Radboud University Medical Center, Zuyderland Medical Center and Canisius-Wilhelmina Hospital in the Netherlands.

Enrolment will take place at the outpatient clinics of the participating hospitals. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in box 1. A total of 120 women must be recruited after a period of 2 years. After inclusion and informed consent, participants will be randomly assigned to either the LVA or conservative (CDT) group with a 1:1 allocation as per a computer-generated randomisation schedule stratified by site using block randomisation. This computer-generated randomisation is done within the electronic Case Report Form in CASTOR EDC. Since only patients with early-stage lymphoedema are included and no large imbalances are expected, no stratification for other demographic data are applied.

Box 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Woman over 18 years old.

Breast cancer treatment with SLNB, ALND or axillary Rt.

Early stage lymphoedema of the arm (stage 1–2a on ISL classification).52

Viable lymphatic vessels as determined by ICG lymphography, stage ≤3.53

At least 3 months conservative therapy (standard of care).

Primary breast cancer.

Unilateral disease and treatment.

Informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

History of earlier lymph reconstruction efforts.

Recurrent breast cancer.

Distant breast cancer metastases.

Bilateral lymphoedema.

Primary congenital lymphoedema.

ALND; axillary lymph node dissection, ICG; indocyanine green, ISL; International Society of Lymphology, Rt; radiotherapy, SLNB; sentinel lymph node biopsy.

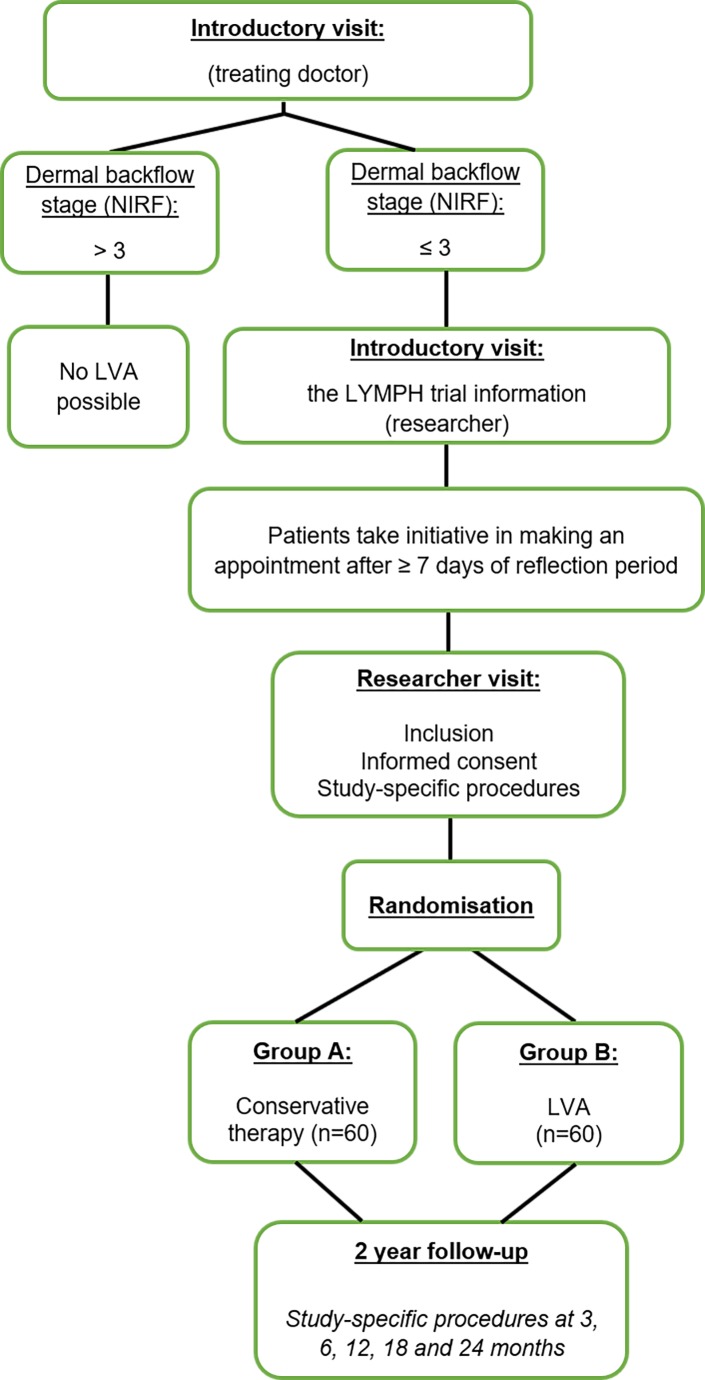

Blinding is not possible in this study, since the operation scars on the arm are easily detectable during the study measurements. However, HRQoL is the primary outcome which is examined by a digital standardised questionnaire. The patients only have access to the questionnaires and the researcher has no influence on this data. The start date of the study is November 2018, and the estimated completion date of the study is November 2022. An overview of the study design is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart: overview of the study design. LVA, lymphaticovenous anastomosis; NIRF, near-infrared fluorescence imaging.

Interventions to be measured

Group A: conservative therapy

The current standard treatment for BCRL is a combination of different methods of conservative therapy, also known as CDT.14 CDT incorporates two stages of treatment. The first treatment phase entails skincare, MLD, exercises aimed at improvement of mobility/range of motion in the shoulder, elbow or wrist joints, and compression therapy through bandaging. Most patients already underwent this phase short after the diagnosis of lymphoedema. CDT in the second treatment phase is aimed at maintenance of the achieved limb volume/circumference reduction through compression therapy with therapeutic elastic compression garment for the arm. Skincare, mobility exercises and MLD is continued in this phase if needed.14 24 Since CDT aim to alleviate symptoms without curative intent, this treatment is mostly lifelong needed. In this study, the patients are followed for 2 years during their regular conservative treatment.

Complex decongestive therapy

Patients allocated to group A will be referred to one of the following dedicated lymphoedema (physical/skin) therapy clinics, if not already treated by one, according to their place of residence for continuation of standard conservative therapy. Only standard conservative therapy, as they would have gotten if not participating in this study, will take place in these clinics, no study measurements.

All women in this study group will be treated according to a protocol which is already in use for patients not participating in this study, since it is considered as the best available standard care. To be able to compare the outcomes for the conservative therapy group, a standardised treatment protocol using the standard lymphatic drainage methods applied in the Netherlands and Germany (‘Verdonkmethod’ and ‘Asdonkmethod’, respectively), will be used in this study. See the online supplementary data for the CDT protocol. Ongoing conservative treatment and the frequency is controlled by the skin therapist. All information regarding conservative treatment is noted in the patient diary.

bmjopen-2019-035337supp001.pdf (3MB, pdf)

Group B: surgical treatment

Lymphaticovenous anastomosis

LVA is a relative minimally invasive registered procedure which can be performed under local anaesthesia. The patient lies comfortable on the operation table, and a limb table is used. The limb is then prepared for surgery.

Before making the incision, a mix of bupivacaine (Marcaïne) and epinephrine (1:100 000) is injected at the site of incision to achieve local anaesthesia and optimal haemostasis.

The following steps of the operation are performed using a surgical microscope. Based on the ICG lymphography mapping, incisions of 1–2 cm are made at the predetermined sites. Lymphatic vessels are identified, and an anastomosis is performed with a similarly sized adjacent recipient vein in the subdermal plane. The anastomosis is usually performed in an end-to-end fashion in case both the lymphatic vessel and vein have approximately the same calibre (otherwise end-to-side). The end-to-end anastomosis is created with an 11–0 suture. The patency of the LVA is confirmed by direct visual examination under the microscope. On average, 1–4 anastomosis are performed in a lymphoedematous arm. The superficial wound is closed using 4–0 Ethilon covered by adhesive plasters and a bandage. The operation length is approximately 2–3 hours.29

Postoperative treatment

From 2 weeks after surgery, when the stitches are removed, patients will be treated with conservative therapy the same way and in the same frequency as preoperatively.43 The participants are treated by the same method as group A if needed, as described in phase 2 (maintenance phase) of the CDT protocol. After 3 months, the plastic surgeon will determine whether conservative therapy can be reduced or stopped, depending on the decrease of subjective complaints and swelling of the arm. The frequency of MLD will be controlled by the skin therapist and noted in the patient diary.

Follow-up moments for both groups will be at 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months. For group A, the follow-up starts from the day of the informed consent signing and for group B from the day of the surgery.

Sample size calculation

We made the following assumptions for the calculation of the sample size to show a statistically significant and clinically relevant difference in quality of life between treatment groups at 12 months’ follow-up as measured with the Lymphedema Functioning, Disability and Health (Lymph-ICF) questionnaire:

Comparing LVA to conservative treatment, the minimal difference in HRQoL that is considered as clinically relevant is 15 points (15% decrease on the 0 to 100 scale) on the Lymph-ICF questionnaire at 12 months’ follow-up.44

To be able to achieve a power of 80%, a total of 45 patients are needed per treatment group, when the SD is 25%, using an alpha of 0.05. If a drop-out rate (loss-to-follow-up and patients with missing data) of 25% is taken into account, a sample size of 60 patients per study group is required and a total of 120 patients will be randomised.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is HRQoL at 12 months’ follow-up. To assess the effectiveness of the treatment we will use the Dutch version of the Lymph-ICF questionnaire. This questionnaire assesses the impairments in function, activity limitations and participation restrictions of patients with upper limb lymphoedema. It is a validated, disease-specific questionnaire, consisting of 29 items (questions) across five domains. Each item is scored on a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) ranging from 0 to 100. The total score on the Lymph-ICF is equal to the sum of the item scores divided by the total number of answered items. A higher score on the Lymph-ICF indicates more impact on the functioning in the daily life related to upper limb lymphoedema.44

HRQoL will be measured at baseline and 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after informed consent (group A), or after surgery (group B).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes are the societal costs, QALYs, incremental cost-effectiveness, discontinuation of conservative treatment and excess limb volume. Assessment will be done at baseline and 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after informed consent (group A), or after surgery (group B).

Costs include healthcare-related costs, costs to patients and family, and costs due to lost productivity. Complete individual-level hospital resource use data (eg, surgical intervention, diagnostic procedures, hospital admissions, outpatient clinic visits) will be measured using medical records and provider information systems. Resource use outside the hospital (eg, lymphoedema therapy, general practitioner visits, out-of-pocket expenses such as for therapeutic elastic garment and over-the-counter drugs, travel costs and quantities of lost paid work) will be determined by means of prospective cost diaries as kept by participants. The cost dairy developed for this study is an adapted version of the iMTA Medical Cost Questionnaire (iMCQ) and iMTA Productivity Cost Questionnaire (iPCQ).45 The Dutch manual for costing research will be used to determine prices for each volume of resource use.46

The EQ-5D-5L is a generic HRQoL measure that can be used to calculate QALYs to be used in the economic evaluation.47 The EQ-5D is a questionnaire responsive to changes in health in breast cancer patients after conclusion of treatment.48

The EQ-5D-5L examines a patient’s HRQoL on the day of the interview. It consist of the EQ-5D-5L descriptive system and a Visual Analog Scale (EQ VAS). The descriptive system comprises five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension has five levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems. Responses to the five items result in a patient’s health state that can be transformed into an index score representing a HRQoL-weight, ranging between 0 (death) and 1 (perfect health).49 These index scores are combined with length of life to calculate the QALYs. The EQ VAS records the patient’s self-rated health with endpoints labelled ‘the best health you can imagine’ at the top and ‘the worst health you can imagine’ at the bottom.

Discontinuation of conservative treatment will be assessed with a patient diary to record the frequency of treatments received (ie, skin therapy visits, number of compression garment, etc).

Lastly, bilateral limb volume measurements will be done using VECTRA 3D imaging and the water displacement method. The excess limb volume is measured as the difference in volume between the affected and unaffected limb which is reported as a percentage of the volume of the unaffected limb. A relative volume reduction (relative to the unaffected arm) as well as an absolute volume reduction (volume reduction of the affected arm at next measurement) will be calculated. The calculated volume will be corrected for the body mass index and for volume differences between the dominant and non-dominant arm.

Besides using the water displacement method, volume measurement will also be done by arm circumference measurement using tape. Both arms will be measured during every visit at the level of the olecranon, 5 and 10 cm proximally, 5 and 10 cm distally, at the level of the wrist, and the dorsum of the hand.

In the outpatient clinic, a fluorescent marker, called indocyanine green (ICG) is injected intracutaneously into the second and fourth finger webspaces of the lymphoedematous limb and a so-called ICG lymphography is performed in search for viable lymphatic vessels. This is a technique using near-infrared fluorescence imaging (NIRF). After 0.05 mL of ICG (5 mg/mL) is injected per webspace, a near-infrared camera is used to visualise the lymphatic vessels. Proximal to the injection sites fluorescent stains are identified. When using the images as a guide, the lymphatic pathways and the sites for incisions for lymphaticovenous anastomoses are marked with a pen and a colour picture is taken. These colour pictures are used to identify the location when LVA will be performed. NIRF will be done at introduction visit and after 12 and 24 months.

Data analysis

For the HRQoL a paired Student’s t-test will be used to evaluate the changes in quality of life scores and in limb volume measurements between preinclusion and the different postinclusion periods of time within individuals from the same study group. For each of the follow-up moments (3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months) the change in quality of life from baseline will be compared between groups using the two sample unpaired t-test, to evaluate short-term and long-term treatment effects. If baseline imbalance is present, assessed qualitatively, adjusted differences per follow-up moment will be computed using linear regression. In addition to statistical testing per follow-up measurement, a linear mixed-effects model will be used to test for an overall difference between the two groups. To account for clustering of measurements at the patient-level, a model with a random intercept and random slope will be used.

Economic evaluation

An economic evaluation will be performed alongside the clinical trial to determine the cost-effectiveness of LVA compared to CDT. The design of the economic evaluation follows the principles of a cost–utility analysis and adheres to the Dutch guideline for economic evaluations in healthcare and the Dutch manual for costing research.50 51 Outcome measures for the economic evaluation will be costs, HRQoL and QALYs. The trial-based evaluation adopts a societal perspective and has a time horizon of 2 years.

An incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), that is, cost per QALY gained, will be calculated by dividing the difference in costs between the two treatments with the difference in QALYs. Bootstrapping techniques will be used to summarise the uncertainty in estimates of incremental costs, effects and the ICER. In addition, cost-effectiveness acceptability curves will show the probability that LVA is cost-effective compared to conservative treatment, given the observed data, for a range of maximum monetary values that a decision-maker might be willing to pay for a QALY gained.

The impact of uncertainty surrounding deterministic parameters (eg, prices) on the ICER will be explored using one-way sensitivity analyses. Results, presented in a tornado diagram, can help determine which parameters are key drivers of the cost-effectiveness results. Pre-determined subgroup analyses will address possible variation between patients (heterogeneity).

Missing values will be imputed using mean substitution or multiple imputation, as appropriate.

Ethics and dissemination

Data monitoring

Data will be handled confidentially. Source data will be stored by the investigator in a locked place. Data of all measurements during follow-up moments, (serious) adverse events (AEs) and digital questionnaires including patient cost diary are stored immediately in the online database of CASTOR EDC. The investigator and project leader only have access to this database with an account with password. Identifying data will be stored in coded form; the key to the form is known only to the supervisor, the investigator, the Dutch Health Care Inspectorate, the study monitors and the members of the review committee.

Harms

AEs are defined as any undesirable experience occurring to a subject during the study, whether or not considered related to the trial procedure. AEs related to the LVA operation or conservative therapy that have a possible impact on the lymphoedema and reported spontaneously by the subject or observed by the investigator or his staff will be recorded directly in CASTOR EDC.

The research team will report the serious AEs (SAEs) through the web portal ToetsingOnline to the accredited METC that approved the protocol, within 7 days of first knowledge for SAEs that result in death or are life threatening followed by a period of maximum of 8 days to complete the initial preliminary report. All other SAEs will be reported within a period of maximum 15 days after the research team has first knowledge of the SAEs.

Auditing

Monitoring of the conduct of the study will be done by the Clinical Trial Center Maastricht on a frequent basis following their protocol as is requested by the Board.

Protocol amendments

Any modifications to the protocol which may impact the study will be notified to the METC that gave a favourable opinion prior to implementation.

Patient and public involvement

The Dutch Network for Lymphedema and Lipedema, and the Patient Advocacy Group, a joint initiative from the Breast Cancer Research Group of the Dutch breast cancer association, were consulted. They provided feedback from the patients’ perspective on our research protocol, patient participation and implementation plan, feasibility, patient information sheet, outcome parameters and the burden for the patients.

Ethical considerations

This study will be conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, recently changed in Fortaleza (2013) and in accordance with the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO).

Dissemination

The results of this study will be disseminated in presentations at academic conferences, publications in peer-reviewed journals and other news media. Data will be kept confidential and will not be shared with the public. Requests for data sharing for appropriate research purposes will be considered on an individual basis after trial completion and after publication of primary manuscripts.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JB, AAPdG, EH, DU, RvdH and SSQ conceived the study and initiated the study design. MK provided statistical and cost-effectiveness expertise. JW, XK, HT, DU, RvdH and SSQ completed the study design and protocol. All authors contributed to refinement of the study protocol and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by ZonMw, grant number 80-85200-98-91044 and Academic Hospital of Maastricht (azM).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Maastricht University Medical Center on 19 December 2018 (NL67059.068.18).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Vignes S, Fau-Prudhomot P, Simon L, et al. . Impact of breast cancer-related lymphedema on working women. Support Care Cancer 2020;28:79–85. 10.1007/s00520-019-04804-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fu MR. Breast cancer-related lymphedema: symptoms, diagnosis, risk reduction, and management. World J Clin Oncol 2014;5:241–7. 10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahmed RL, Schmitz KH, Prizment AE, et al. . Risk factors for lymphedema in breast cancer survivors, the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;130:981–91. 10.1007/s10549-011-1667-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nesvold I-L, Fosså SD, Holm I, et al. . Arm/shoulder problems in breast cancer survivors are associated with reduced health and poorer physical quality of life. Acta Oncol 2010;49:347–53. 10.3109/02841860903302905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ahmed RL, Prizment A, Lazovich D, et al. . Lymphedema and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: the Iowa women's health study. JCO 2008;26:5689–96. 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Engel J, Kerr J, Schlesinger-Raab A, et al. . Axilla surgery severely affects quality of life: results of a 5-year prospective study in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2003;79:47–57. 10.1023/A:1023330206021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chachaj A, Małyszczak K, Pyszel K, et al. . Physical and psychological impairments of women with upper limb lymphedema following breast cancer treatment. Psychooncology 2010;19:299–305. 10.1002/pon.1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DiSipio T, Rye S, Newman B, et al. . Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:500–15. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70076-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dominick SA, Natarajan L, Pierce JP, et al. . The psychosocial impact of lymphedema-related distress among breast cancer survivors in the WHEL study. Psychooncology 2014;23:1049–56. 10.1002/pon.3510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fu MR, Ridner SH, Hu SH, et al. . Psychosocial impact of lymphedema: a systematic review of literature from 2004 to 2011. Psychooncology 2013;22:1466–84. 10.1002/pon.3201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oliveri JM, Day JM, Alfano CM, et al. . Arm/hand swelling and perceived functioning among breast cancer survivors 12 years post-diagnosis: CALGB 79804. J Cancer Surviv 2008;2:233–42. 10.1007/s11764-008-0065-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Petrek JA, Senie RT, Peters M, et al. . Lymphedema in a cohort of breast carcinoma survivors 20 years after diagnosis. Cancer 2001;92:1368–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Voogd AC, Ververs JMMA, Vingerhoets AJJM, et al. . Lymphoedema and reduced shoulder function as indicators of quality of life after axillary lymph node dissection for invasive breast cancer. Br J Surg 2003;90:76–81. 10.1002/bjs.4010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Venereologie NvvDe Richtlijn lymfoedeem. Multidisciplinaire evidence-based richtlijn, 2014. Available: www.lymfoedeem.nl

- 15. KNL Richtlijn Mammacarcinoom; 2012.

- 16. Ashikaga T, Krag DN, Land SR, et al. . Morbidity results from the NSABP B-32 trial comparing sentinel lymph node dissection versus axillary dissection. J Surg Oncol 2010;102:111–8. 10.1002/jso.21535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coriddi M, Khansa I, Stephens J, et al. . Analysis of factors contributing to severity of breast Cancer–Related lymphedema. Ann Plast Surg 2015;74:22–5. 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31828d7285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Monleon S, Murta-Nascimento C, Bascuas I, et al. . Lymphedema predictor factors after breast cancer surgery: a survival analysis. Lymphat Res Biol 2015;13:268–74. 10.1089/lrb.2013.0042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tsai RJ, Dennis LK, Lynch CF, et al. . The risk of developing arm lymphedema among breast cancer survivors: a meta-analysis of treatment factors. Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:1959–72. 10.1245/s10434-009-0452-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnson AR, Kimball S, Epstein S, et al. . Lymphedema incidence after axillary lymph node dissection: quantifying the impact of radiation and the lymphatic microsurgical preventive healing approach. Ann Plast Surg 2019;82:S234–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grada AA, Phillips TJ. Lymphedema: pathophysiology and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;77:1009–20. 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Uzkeser H, Karatay S, Erdemci B, et al. . Efficacy of manual lymphatic drainage and intermittent pneumatic compression pump use in the treatment of lymphedema after mastectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer 2015;22:300–7. 10.1007/s12282-013-0481-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vignes S, Porcher R, Arrault M, et al. . Long-Term management of breast cancer-related lymphedema after intensive decongestive physiotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007;101:285–90. 10.1007/s10549-006-9297-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McNeely ML, Peddle CJ, Yurick JL, et al. . Conservative and dietary interventions for cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer 2011;117:1136–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dayes IS, Whelan TJ, Julian JA, et al. . Randomized trial of decongestive lymphatic therapy for the treatment of lymphedema in women with breast cancer. JCO 2013;31:3758–63. 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.7192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koshima I, Inagawa K, Urushibara K, et al. . Supermicrosurgical Lymphaticovenular anastomosis for the treatment of lymphedema in the upper extremities. J Reconstr Microsurg 2000;16:437–42. 10.1055/s-2006-947150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Basta MN, Gao LL, Wu LC. Operative treatment of peripheral lymphedema: a systematic meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of lymphovenous microsurgery and tissue transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;133:905–13. 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chang DW. Lymphaticovenular bypass for lymphedema management in breast cancer patients: a prospective study. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;126:752–8. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181e5f6a9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang DW, Suami H, Skoracki R. A prospective analysis of 100 consecutive lymphovenous bypass cases for treatment of extremity lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;132:1305–14. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a4d626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Damstra RJ, Voesten HGJ, van Schelven WD, et al. . Lymphatic venous anastomosis (LVA) for treatment of secondary arm lymphedema. A prospective study of 11 LVA procedures in 10 patients with breast cancer related lymphedema and a critical review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;113:199–206. 10.1007/s10549-008-9932-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Furukawa H, Osawa M, Saito A, et al. . Microsurgical lymphaticovenous implantation targeting dermal lymphatic backflow using indocyanine green fluorescence lymphography in the treatment of postmastectomy lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127:1804–11. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31820cf2e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mihara M, Hara H, Hayashi Y, et al. . Upper-Limb lymphedema treated aesthetically with lymphaticovenous anastomosis using indocyanine green lymphography and noncontact vein visualization. J Reconstr Microsurg 2012;28:327–32. 10.1055/s-0032-1311691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nagase T, Gonda K, Inoue K, et al. . Treatment of lymphedema with lymphaticovenular anastomoses. Int J Clin Oncol 2005;10:304–10. 10.1007/s10147-005-0518-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Penha TR, Ijsbrandy C, Hendrix NA, et al. . Microsurgical techniques for the treatment of breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review. J Reconstr Microsurg 2013;29:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Torrisi JS, Joseph WJ, Ghanta S, et al. . Lymphaticovenous bypass decreases pathologic skin changes in upper extremity breast cancer-related lymphedema. Lymphat Res Biol 2015;13:46–53. 10.1089/lrb.2014.0022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yamamoto Y, Horiuchi K, Sasaki S, et al. . Follow-Up study of upper limb lymphedema patients treated by microsurgical lymphaticovenous implantation (MLVI) combined with compression therapy. Microsurgery 2003;23:21–6. 10.1002/micr.10080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cornelissen AJM, Beugels J, Ewalds L, et al. . Effect of Lymphaticovenous anastomosis in breast cancer-related lymphedema: a review of the literature. Lymphat Res Biol 2018;16:426–34. 10.1089/lrb.2017.0067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Winters H, Tielemans HJP, Verhulst AC, et al. . The long-term patency of Lymphaticovenular anastomosis in breast Cancer–Related lymphedema. Ann Plast Surg 2019;82:196–200. 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Salgarello M, Mangialardi M, Pino V, et al. . A prospective evaluation of health-related quality of life following Lymphaticovenular anastomosis for upper and lower extremities lymphedema. J Reconstr Microsurg 2018;34:701–7. 10.1055/s-0038-1642623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Giacalone G, Yamamoto T. Supermicrosurgical lymphaticovenous anastomosis for a patient with breast lymphedema secondary to breast cancer treatment. Microsurgery 2017;37:680–3. 10.1002/micr.30139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cornelissen AJM, Kool M, Lopez Penha TR, et al. . Lymphatico-venous anastomosis as treatment for breast cancer-related lymphedema: a prospective study on quality of life. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;163:281–6. 10.1007/s10549-017-4180-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Winters H, Tielemans HJP, Hameeteman M, et al. . The efficacy of lymphaticovenular anastomosis in breast cancer-related lymphedema. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;165:321–7. 10.1007/s10549-017-4335-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Masia J, Pons G, Nardulli M. Combined surgical treatment in breast cancer-related lymphedema. J Reconstr Microsurg 2016;32:016–27. 10.1055/s-0035-1544182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Devoogdt N, Van Kampen M, Geraerts I, et al. . Lymphoedema functioning, disability and health questionnaire (Lymph-ICF): reliability and validity. Phys Ther 2011;91:944–57. 10.2522/ptj.20100087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bouwmans Cea Handleiding iMTA medical cost questionnaire (iMCQ) 2013.

- 46. Lopez Penha TR, van Roozendaal LM, Smidt ML, et al. . The changing role of axillary treatment in breast cancer: who will remain at risk for developing arm morbidity in the future? The Breast 2015;24:543–7. 10.1016/j.breast.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. . Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kimman ML, Dirksen CD, Lambin P, et al. . Responsiveness of the EQ-5D in breast cancer patients in their first year after treatment. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:11 10.1186/1477-7525-7-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. M Versteegh M, M Vermeulen K, M A A Evers S, et al. . Dutch tariff for the five-level version of EQ-5D. Value Health 2016;19:343–52. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zorginstituut Kostenhandleiding: Methodologie van kostenonderzoek en referentieprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg; 2015.

- 51. Zorginstituut Richtlijn voor Het uitvoeren van economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg; 2015.

- 52. Executive C, Executive Committee . The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema: 2016 consensus document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology 2016;49:170–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Narushima M, Yamamoto T, Ogata F, et al. . Indocyanine green lymphography findings in limb lymphedema. J Reconstr Microsurg 2016;32:72–9. 10.1055/s-0035-1564608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-035337supp001.pdf (3MB, pdf)