Abstract

Objective

Using a summary measure of health inequalities, this study evaluated the distribution of adverse birth outcomes (ABO) and related maternal risk factors across area-level socioeconomic status (SES) gradients in urban and rural Alberta, Canada.

Design

Cross-sectional study using a validated perinatal clinical registry and an area-level SES.

Setting

The study was conducted in Alberta, Canada. Data about ABO and related maternal risk factors were obtained from the Alberta Perinatal Health Program between 2006 and 2012. An area-level SES index derived from census data (2006) was linked to the postal code at delivery.

Participants

Women (n=3 30 957) having singleton live births with gestational age ≥22 weeks.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

We estimated concentration indexes to assess inequalities across SES gradients in both rural and urban areas (CIdxR and CIdxU, respectively) for spontaneous preterm birth (PTB), small for gestational age (SGA), large for gestational age (LGA), gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, smoking and substance use during pregnancy and pre-pregnancy weight >91 kg.

Results

The highest health inequalities disfavouring low SES groups were identified for substance abuse and smoking in rural areas (CIdxR−0.38 and −0.23, respectively). Medium inequalities were identified for LGA (CIdxR−0.08), pre-pregnancy weight >91 kg (CIdxR−0.07), substance use (CIdxU−0.15), smoking (CIdxU−0.14), gestational diabetes (CIdxU−0.10) and SGA (CIdxU−0.07). Low inequalities were identified for PTB (CIdxR−0.05; CIdxU−0.05) and gestational diabetes (CIdxR−0.04). Inequalities disfavouring high SES groups were identified for gestational hypertension (CIdxR+0.04), SGA (CIdxR+0.03) and LGA (CIdxU+0.03).

Conclusions

ABO and related maternal risk factors were unequally distributed across the socioeconomic gradient in urban–rural settings, with the greatest concentrations in lower SES groups of rural areas. Future research is needed on underlying mechanisms driving SES gradients in perinatal health across the rural–urban spectrum.

Keywords: epidemiology, maternal medicine, public health, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This population-based study used a high-quality clinical perinatal registry to quantify health inequalities for adverse birth outcomes and related risk factors across socioeconomic groups in rural and urban Alberta (Canada), a province with universal and free access to medically necessary hospital and physician services for its inhabitants.

We used a well-known and robust method, the concentration index, to compare socioeconomic inequalities in perinatal health in urban and rural areas.

The area-level socioeconomic status (SES) index used for this study is based on the 2006 census data. Potential misclassification of the SES may occur as we are assuming no changes in area-level SES index between 2006 and 2012.

Substance abuse and smoking prevalence are expected to be underestimated since they are self-reported.

Introduction

Adverse birth outcomes such as preterm birth (PTB), small for gestational age (SGA) and large for gestational age (LGA) are major drivers of morbidity and mortality in neonates and infants and important contributors to long-term physical and psychological health.1–3 Many of the determinants of adverse birth outcomes start in pregnancy and even before conception. Maternal factors implicated with the occurrence of adverse outcomes at birth include pre-pregnancy overweight, maternal health problems during pregnancy (eg, gestational hypertension and diabetes) and certain behaviours such as smoking and substance use.1 4 All these perinatal exposures and outcomes constitute the ‘canary in the coal mine’ as fundamental early life indicators of the impact of social and structural determinants of health operating in a very sensitive period of human life.5 Health inequalities at birth would then represent a magnifying glass of preconception disadvantages, and a forecast for adult inequalities.6

Socioeconomic inequalities in health are quantitative differences in the occurrence of health outcomes across socioeconomic groups,7 and a topic of great interest in social epidemiology to better understand the structural causes of health and disease.8 9 Recent systematic reviews have examined the influences of socioeconomic characteristics on the risk of adverse birth outcomes, suggesting a strong link between area-level socioeconomic status (SES) gradients and a variety of adverse birth outcomes.10–13 Knowledge gaps remain to fully understand the interconnections between socioeconomic characteristics, area of residence and maternal and perinatal health. Exploring this association is particularly important as both urban and rural living have been also associated with adverse health outcomes.14 However, it is unknown whether health advantages and disadvantages of living in urban and rural areas are equally distributed in all socioeconomic groups or if gradients in health exist affecting the more disadvantaged groups. On the one hand, diverse theories about urban residence posit that cities create harmful environments for human health.15–17 Alternatively, rural areas encompassing vast extensions of land have been also associated with poor outcomes.18 Despite the growing interest in recent years about the role of spatial19 and socioeconomic-driven inequalities9 in the distribution of adverse birth outcomes and associated maternal factors, studies in this area have mainly evaluated urban populations. Few studies14 20 have examined the relationship between adverse birth outcomes and neighbourhood deprivation in rural versus urban communities, a relevant health policy issue in countries where the access to health services is universal. The study of socioeconomic health inequalities has been traditionally based on population-at-risk approaches, which have underpinned the socioeconomic gradient as a risk factor for poor health.21 22 The majority of these studies have used analytical approaches based on measures of association (ie, regression and Pearson coefficients), and measures of potential impact (ie, attributable proportions23) while other methods based on summary measures of health inequality have been seldom explored.23

Using the health concentration index approach, this study quantified health inequalities in the distribution of PTB, SGA, LGA and related known maternal factors (ie, pre-pregnancy weight >91 kg, gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, self-reported smoking and substance use during pregnancy) in urban and rural Alberta (Canada) across a socioeconomic gradient. Like all other Canadian provinces, Alberta has a universal, publicly funded healthcare system that guarantees Albertans receive free access to medically necessary hospital and physician services. The concentration index quantifies the magnitude of perinatal health inequalities across different populations while taking into account both the distribution of the study population across the different socioeconomic groups. We hypothesise that adverse birth outcomes in urban and rural areas are distributed differently and potentially related to socioeconomic gradients within the two areas of residence.

Methods

This study is part of a broader environmental health research that explored associations between environmental and social factors with adverse birth outcomes.24

Study design and population

We conducted a cross-sectional population-based study using provincial health data from Alberta (Canada) for the period from 1 January 2006 to 31 December 2012. Alberta is a culturally diverse province located in Western Canada with a population of 4 067 175 inhabitants in 2016 with approximately 83% living in urban centres.25

The study population consisted of all women having singleton live births with gestational age ≥22 completed weeks during the study period. We used data from the Alberta Perinatal Health Program (APHP), which is a validated clinical perinatal registry that collects data directly from the provincial delivery record for all births occurring in a hospital or attended by a registered midwife at home in Alberta. Delivery characteristics and newborn health status recorded in the APHP include birth weight, gestational age at delivery in completed weeks, maternal postal code of residence at delivery, lifestyle behaviours before and during pregnancy, maternal health status, obstetric interventions and neonatal outcomes.

Adverse birth outcomes

PTB was defined as newborn with less than 37 completed weeks of gestational age. Newborns were identified as SGA (birth weight below the 10th percentile) and LGA (birth weight above the 90th percentile) according to Canadian sex-age specific, population-based standards.26

Maternal factors related with PTB, SGA and LGA

Information on the following maternal factors was extracted from the APHP: age at delivery, pre-pregnancy weight >91 kg, gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes (documented hyperglycaemia with diagnosis during current pregnancy only), self-reported smoking (anytime during pregnancy) and substance use during pregnancy (three drinks or more on any occasion during pregnancy or one or more alcohol drinks per day while pregnant, and/or drug dependency, inappropriate or excessive use of any substance).

Definitions of urban and rural maternal place of residence at delivery

We used the 2006 geographic standards provided by Statistics Canada to classify areas of residence (urban, rural) and georeferenced data for postal code locations.27 The six-character postal codes of the maternal place of residence at delivery were classified as rural or urban according to population concentration and density, based on the 2006 geographic framework. First, postal codes were assigned to their corresponding dissemination area (DA: a census geographic area larger than postal codes with a population of 400–700 persons according to the 2006 census geography definition).28 A vector overlay of postal code locations within the Statistics Canada DA boundary file was performed to capture postal codes not included in the 2006 geographic framework.29 The DA geolocation of postal codes was then used to classify maternal place of residence at delivery into urban or rural. A DA was considered urban if it had a minimum population concentration of 1000 persons and a population density of at least 400 persons per square kilometre based on the 2006 Census population count; otherwise, the DA was classified as rural.28

Socioeconomic status gradients

The 2006 SES index developed by Chan et al 30 was chosen to represent area-based socioeconomic gradients in the study population. This index is based on area-level information about education attainment, employment status, income, marital status, home ownership, transport mode and year of home construction, among other variables taken from the 2006 national census. In addition, the SES index incorporated a measure of Indigenous status or the human developmental index of the individuals’ country of origin as a proxy for ethnicity, which is a variable that has been linked to perinatal outcomes.11 31 The SES index was ranked in quintiles (Q1–Q5) at the DA level, where Q1 and Q5 correspond to the lowest and highest SES, respectively.

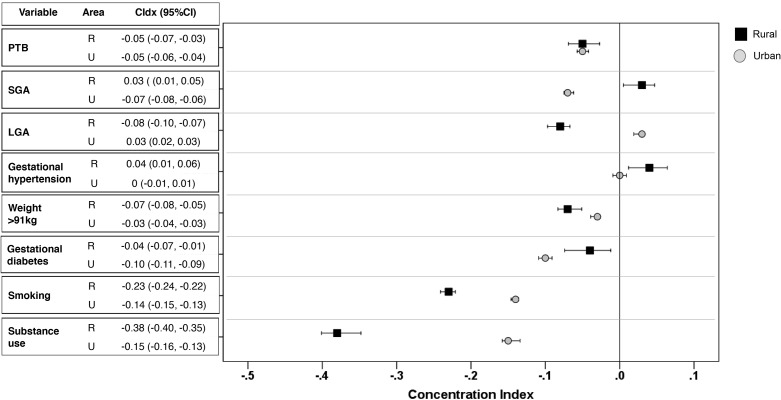

Statistical analyses

We calculated the period prevalence of PTB, SGA, LGA and related maternal factors in both urban and rural settings across SES quintiles. We calculated the absolute concentration index23 with 95% CI to measure inequalities in the period prevalence of adverse birth outcomes and related maternal factors by SES groups in both rural (CIdxR) and urban (CIdxU) settings. Briefly, the concentration index measures inequality in the distribution of a health variable (ie, adverse birth outcomes or related maternal factors) over the population grouped across the SES quintiles.23 32 Values of the concentration index range from −1 to +1 where the larger the absolute value of the concentration index, the higher the level of health inequalities.22 A value of zero indicates the absence of a socioeconomic gradient in the distribution of adverse birth outcomes and related factors in the study population. Positive values indicate a concentration of the health outcome among advantaged groups, while negative values indicate a concentration of the health outcome among the more disadvantaged ones.33 Degrees of inequalities were interpreted based on the absolute value of the concentration index as low (≤ |0.05|), medium (|0.06 to 0.19|) and high (≥ |0.20|).34

We used forest plots to display CIdxR and CIdxU values with 95% CI for both adverse birth outcomes and related maternal factors. If the estimate of the concentration index and its 95% CI cross zero (no inequality), all SES groups have the same distribution of the health outcome and no socioeconomic gradient exists. If concentration index and 95% CI values are to the left of the no inequality line, a socioeconomic gradient exists with lower SES groups having a higher concentration of the outcomes. If values are to the right of the no inequality line, the outcome is concentrated in higher SES groups. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata V.15.1 (StataCorp.).

Patient or public involvement

No patient involved.

Results

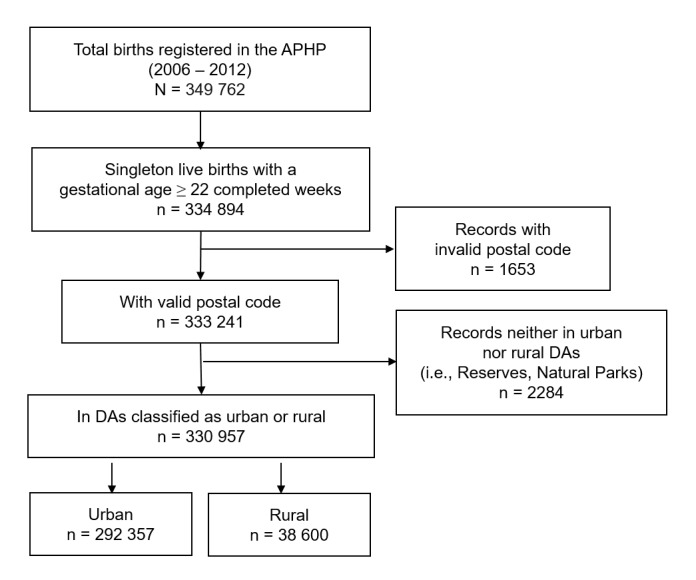

A total of 349 762 births occurred in Alberta between 2006 and 2012, of which 334 894 were singleton live births with gestational age ≥22 of completed weeks. A total of 330 957 deliveries were included in the analyses after geographic classification (figure 1), of which 292 357 were births from women living in urban settings, and 38 600 from those living in rural areas at time of delivery. Small numbers of missing values were present for maternal weight, gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes and smoking during pregnancy in the urban (0.81%; n=2667) and rural areas (1.3%; n=497). There were no missing values for PTB, SGA and LGA categories in both urban and rural areas.

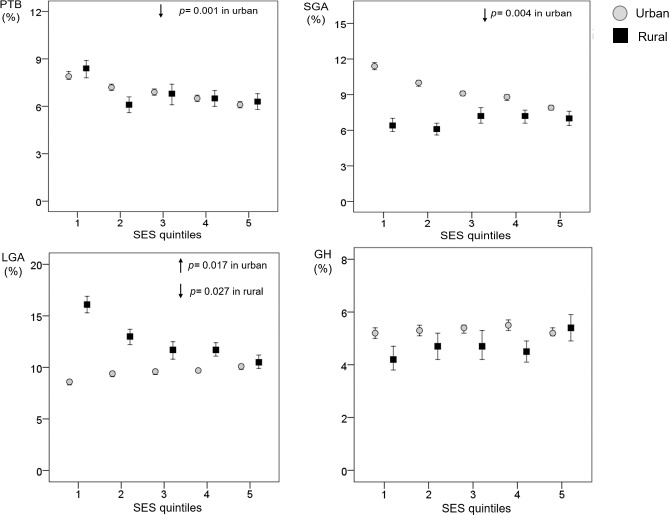

Figure 1.

Study population flow diagram.

Prevalence of adverse birth outcomes and related maternal factors in urban and rural settings

Table 1 and figures 2 and 3 show the prevalence of adverse birth outcomes and maternal factors by SES groups in rural and urban areas. The overall PTB prevalence was similar in both rural and urban settings (6.8%), with small differences across SES quintiles and reductions as the SES increased in urban areas. The prevalence of SGA was consistently higher in urban areas (9.2% (95% CI 9.1% to 9.3%) versus 6.8% (95% CI 6.5% to 7.0%)). Urban prevalence of SGA decreased with higher SES while rural SGA prevalence increased with higher SES. LGA prevalence was higher in rural areas (12.7% (95% CI 12.3% to 13.0%)) and decreased as the SES increased (Q1: 16.1% (95% CI 15.3% to 16.9%); Q5: 10.5% (95% CI 9.9% to 11.2%)). In urban settings, LGA prevalence increased from 8.6% (95% CI 8.3% to 8.8%) to 10.1% (95% CI 9.8% to 10.3%) across the SES gradient.

Table 1.

Prevalence of ABO and maternal risk factors by socioeconomic quintiles in urban and rural Alberta (2006–2012)

| Maternal area of residence at delivery | Adverse birth outcomes | Maternal risk factors | |||||||

| PTB | SGA | LGA | Weight>91 kg | Gestational hypertension | Gestational diabetes | Smoking | Substance use | ||

| Urban | N | 19 924 | 26 893 | 27 874 | 25 987 | 15 452 | 15 147 | 44 004 | 8634 |

| Overall (% (95% CI)) | 6.8 (6.7 to 6.9) | 9.2 (9.1 to 9.3) | 9.5 (9.4 to 9.6) | 9.0 (8.9 to 9.1) | 5.3 (5.2 to 5.4) | 5.2 (5.1 to 5.3) | 15.2 (15.0 to 15.3) | 3.0 (2.9 to 3.0) | |

| Q1:lowest SES | 7.9 (7.7 to 8.2) | 11.4 (11.1 to 11.7) | 8.6 (8.3 to 8.8) | 9.0 (8.7 to 9.3) | 5.2 (5.0 to 5.4) | 7.2 (7.0 to 7.5) | 20.1 (19.8 to 20.5) | 4.3 (4.1 to 4.4) | |

| Q2 | 7.2 (7.0 to 7.4) | 10 (9.7 to 10.2) | 9.4 (9.1 to 9.6) | 9.9 (9.6 to 10.1) | 5.3 (5.1 to 5.5) | 5.8 (5.6 to 6.0) | 19.1 (18.8 to 19.5) | 3.5 (3.3 to 3.6) | |

| Q3 | 6.9 (6.7 to 7.1) | 9.1 (8.9 to 9.3) | 9.6 (9.3 to 9.8) | 9.5 (9.3 to 9.8) | 5.4 (5.2 to 5.5) | 4.9 (4.7 to 5.1) | 16.6 (16.3 to 16.9) | 3.2 (3.1 to 3.4) | |

| Q4 | 6.5 (6.3 to 6.7) | 8.8 (8.5 to 9.0) | 9.7 (9.5 to 9.9) | 8.8 (8.5 to 9.0) | 5.5 (5.3 to 5.7) | 5.0 (4.8 to 5.1) | 13.4 (13.1 to 13.7) | 2.5 (2.4 to 2.7) | |

| Q5:highest SES | 6.1 (5.9 to 6.3) | 7.9 (7.7 to 8.1) | 10.1 (9.8 to 10.3) | 8.1 (7.9 to 8.2) | 5.2 (5.1 to 5.4) | 4.1 (4.0 to 4.3) | 10.0 (9.8 to 10.2) | 2.0 (1.9 to 2.1) | |

| Rural | N | 2636 | 2616 | 4895 | 4248 | 1790 | 1360 | 9170 | 2112 |

| Overall (% (95% CI)) | 6.8 (6.6 to 7.1) | 6.8 (6.5 to 7.0) | 12.7 (12.3 to 13.0) | 11.2 (10.8 to 11.5) | 4.7 (4.5 to 4.9) | 3.6 (3.4 to 3.8) | 24.1 (23.6 to 24.5) | 5.5 (5.2 to 5.7) | |

| Q1:lowest SES | 8.4 (7.8 to 8.9) | 6.4 (5.9 to 7.0) | 16.1 (15.3 to 16.9) | 13.5 (12.8 to 14.2) | 4.2 (3.8 to 4.7) | 4.5 (4.1 to 5.0) | 45.7 (44.7 to 46.8) | 14.3 (13.6 to 15.0) | |

| Q2 | 6.1 (5.6 to 6.6) | 6.1 (5.6 to 6.6) | 13.0 (12.2 to 13.7) | 11.4 (10.6 to 12.1) | 4.7 (4.2 to 5.2) | 3.1 (2.7 to 3.5) | 19.1 (18.2. 19.9) | 2.9 (2.5 to 3.3) | |

| Q3 | 6.8 (6.1 to 7.4) | 7.2 (6.6 to 7.9) | 11.7 (10.8 to 12.5) | 10.7 (9.9 to 11.5) | 4.7 (4.2 to 5.3) | 3.2 (2.7 to 3.7) | 20.6 (19.6 to 21.7) | 3.8 (3.3 to 4.3) | |

| Q4 | 6.5 (6.0 to 7.0) | 7.2 (6.6 to 7.7) | 11.7 (11.1 to 12.4) | 10.6 (10.0 to 11.3) | 4.5 (4.1 to 4.9) | 3.3 (2.9 to 3.7) | 20.1 (19.2 to 20.9) | 3.2 (2.8 to 3.6) | |

| Q5:highest SES | 6.3 (5.8 to 6.8) | 7.0 (6.4 to 7.6) | 10.5 (9.9 to 11.2) | 9.4 (8.8 to 10.1) | 5.4 (4.9 to 5.9) | 3.5 (3.1 to 3.9) | 12.7 (12.0 to 13.4) | 2.2 (1.9 to 2.5) | |

ABO, adverse birth outcomes; LGA, large for gestational age; n, number of cases; PTB, preterm birth; Q, quintiles; SES, socioeconomic status; SGA, small for gestational age.

Figure 2.

Period prevalence (with 95% CI) of preterm birth (PTB), small for gestational age (SGA), large for gestational age (LGA) and gestational hypertension (GH) across socioeconomic status (SES) quintiles in urban and rural settings. Footnote: the linear gradient for the prevalence by health outcome across the SES quintiles was tested using regression analysis. The p value for the linear gradient was incorporated into the graph when it was statistically significant (p<0.05). Note that the y-axis scaling (%) differs among the different panels.

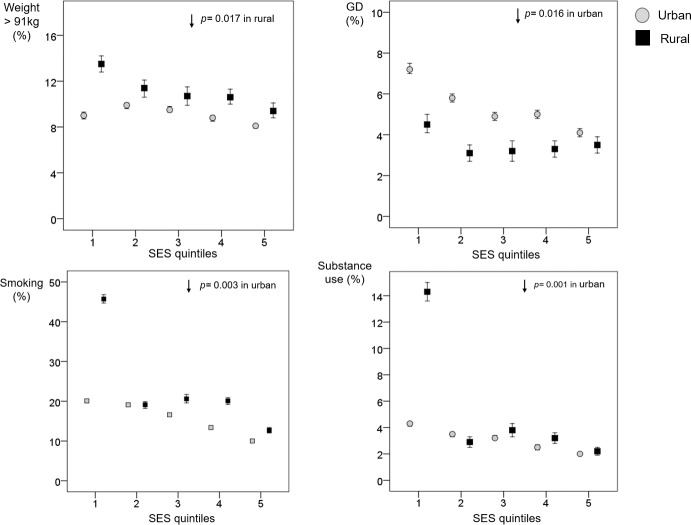

Figure 3.

Period prevalence (with 95% CI) of pre-pregnancy weight >91 kg (Weight > 91 kg), gestational diabetes (GD), smoking and substance use during pregnancy across socioeconomic status (SES) quintiles in urban and rural settings. Footnote: the linear gradient for the prevalence by health outcome across the SES quintiles was tested using regression analysis. The p value for the linear gradient was incorporated into the graph when it was statistically significant (p<0.05). Note that the y-axis scaling (%) differs among the different panels.

Gestational hypertension was more prevalent in urban (5.3% (95% CI 5.2% to 5.4%)) versus rural settings (4.7% (95% CI 4.5% to 4.9%)) with similar distributions across the SES groups in both urban and rural areas of residence. The proportion of women with pre-pregnancy weight >91 kg was higher in rural (11.2% (95% CI 10.8% to 11.5%)) versus urban areas (9.0% (95% CI 8.9% to 9.1%)) and both settings had a clear gradient across the SES groups with highest values in the most deprived group. The prevalence of gestational diabetes was higher in urban (5.2% (95% CI 5.1% to 5.3%)) than in rural settings (3.6% (95% CI 3.4% to 3.8%)), with larger differences between the lowest and highest SES groups (Q1 : 7.2% (95% CI 5.1% to 5.3%); Q5: 4.1% (95% CI 4.0% to 4.3%)). In rural settings, gestational diabetes prevalence was particularly high in the most disadvantaged group compared with the other SES groups.

Smoking during pregnancy was higher in rural (24.1% (95% CI 23.6% to 24.5%)) versus urban (15.2% (95% CI 15.0% to 15.3%)) areas, particularly in the most deprived rural SES group (Q1: 45.7% (95% CI 44.7% to 46.8%)). For both urban and rural areas, there was a SES gradient in the prevalence of smoking in pregnancy with lower SES groups having the higher burden of disease. Substance use during pregnancy was more prevalent in rural areas (5.5% (95% CI 5.2% to 5.7%)) and showed slight variations in the distribution across SES groups. Urban prevalence of substance use during pregnancy (3.0% (95% CI 2.9% to 3.0%)) showed a gradient across SES groups, with decreasing numbers as SES increased.

Concentration indices by SES groups in urban and rural settings

Figure 4 shows rural (CIdxR) and urban (CIdxU) concentration indexes for adverse birth outcomes and related maternal factors. The majority of adverse birth outcomes and related maternal factors were unequally distributed, and concentrated in the lower SES groups except for SGA (which was concentrated in higher SES groups of rural areas; CIdxR 0.03 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.05)), LGA (concentrated in urban higher SES groups; CIdxU 0.03 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.03)) and gestational hypertension (concentrated in higher SES groups of rural areas; CIdxR 0.04 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.06)). There were no inequalities in the distribution of gestational hypertension by SES groups in urban areas. The highest degrees of health inequalities across SES groups were found for substance abuse and smoking in rural areas (CIdxR |0.38| and |0.23|, respectively). Medium inequalities across SES groups were identified for LGA and pre-pregnancy weight >91 kg in rural areas (CIdxR |0.08| and |0.07|, respectively) and for substance use (CIdxU |0.15|), smoking (CIdxU |0.14|), gestational diabetes (CIdxU |0.10|) and SGA (CIdxU |0.07|) in urban settings. A low degree of inequalities was identified in the distribution of PTB (CIdxR and CIdxU 0.05|), SGA (CIdxR |0.03|), gestational hypertension (CIdxR |0.04|) and gestational diabetes (CIdxR |0.04|) across SES in rural settings. LGA (CIdxU |0.03|), gestational hypertension (CIdxU |0.01|) and pre-pregnancy weight >91 kg (CIdxU |0.03|) also had a low degree of inequalities across SES groups in urban settings.

Figure 4.

Concentration index (CIdx) of adverse birth outcomes and related maternal factors among urban and rural populations in Alberta (2006–2012). Weight > 91 kg pertains to pre-pregnancy weight > 91 kg. Horizontal lines indicate 95% CI around the concentration index (CIdx). Degrees of inequalities were interpreted based on the absolute value of the concentration index as low (≤ |0.05|), medium (|0.06 to 0.19|) and high (≥ |0.20|).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional population-based study, we used concentration indexes to examine SES gradients for adverse birth outcomes and related maternal behavioural factors in urban and rural areas of Alberta. The results revealed that adverse birth outcomes and related maternal factors are unequally distributed across the socioeconomic gradient in the urban–rural divide, with the majority of them concentrating in lower SES groups. Specifically, the concentration indexes of PTB and related maternal factors (pre-pregnancy weight >91 kg, gestational diabetes, smoking and substance abuse) demonstrated the existence of a gradient of perinatal inequalities in both urban and rural areas that affected the lowest SES groups. The largest socioeconomic gradient was observed for smoking and substance use during pregnancy as lower SES groups from rural areas were affected the most.

The pathways for the associations among area-level deprivation, maternal health, and adverse birth outcomes are complex and likely multifactorial. We found that area-level deprivation and geographic area of residence differentially associate with fetal growth and duration of gestation. One potential explanation for these results is that women residing in rural areas are more vulnerable to neighbourhood deprivation.35 For example, there is evidence that pregnant women in the younger groups living in rural areas have the highest odds for adverse pregnancy outcomes compared with their counterparts living in urban settings.36 In addition, lower SES, more unhealthy maternal behaviours and more limited access to healthcare resources and adequate prenatal care have been described among rural residents compared with those in urban areas.18 37–39 The existence of synergistic deleterious influences of area-level determinants and individual factors may account for these differences. Other potential explanations may be linked to low health literacy in rural populations about the effects of lifestyle behaviours in childbearing age and the impact on birth outcomes, and shortages in resources to stay better informed than women living in more urbanised areas.40 Systemic and structural influences such as food security, health services access may also account for the socioeconomic gradient in the urban–rural divide. Finally, the ‘healthy migration’ effect41 can contribute to our study results. It is possible that healthy women living in rural and remote areas are most likely to migrate to more urbanised areas, leaving behind their counterparts at a higher risk of experiencing adverse birth outcomes.

To our knowledge, few studies have evaluated SES gradients in adverse birth outcomes and related maternal factors in Canada. One study42 evaluated socioeconomic inequality in health across the provinces in Canada over time (1998–2011) suggesting that those inequalities have widened over time, especially among women. However, in that study Alberta was merged with Saskatchewan and Manitoba to form the Prairies. A few studies have evaluated the influence of area-level SES on adverse birth outcomes in rural and urban areas using other epidemiological approaches and yielding conflicting results.35 43

Strengths and limitations of this study

We used a well-known and robust method, the concentration index, to compare socioeconomic inequalities in perinatal health in urban and rural areas.22 32 33 Compared with other approaches to the study of health inequalities, the concentration index has some advantages. For example, results are not biased by the sample size of the SES strata in the study population. The graphical display of the concentration index allows a visual representation of the dominance relationships in the distribution of the outcomes across SES strata and between urban and rural groups.

Our study had some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. This study described the prevalence of maternal factors related to adverse birth outcomes in Alberta for a singleton birth cohort; thus, generalisation of the analysis of concentration indexes to other places or populations is limited. There are other limitations in this study inherent to the cross-sectional nature of the study and the lack of detailed clinical information available in the APHP regarding maternal factors. For example, the variable pre-pregnancy maternal weight >91 kg was used as a proxy for overweight/obesity since information on the exact weight and height is not available in the APHP to calculate body mass index. Another limitation of the study is the reliance on self-reporting of smoking and substance use during pregnancy. Self-reporting is a common problem in population studies44 as these factors may introduce non-differential bias in the evaluation of the exposures.

Another potential limitation in the study is that the SES measure incorporates area-level census information about income in the calculation. In rural areas, where farming and informal economic sectors are highly prevalent, income may not be precisely estimated and this may introduce some misclassification of the SES in the calculations. Despite this, area-level SES indicators have been used in health research as a good proxy for individual-level measures,45 46 and our analyses were disaggregated by SES quantiles in urban and rural areas separately. This approach allowed the identification of subgroups where special attention is needed in both urban and rural areas. Area-level measures of SES gradients are important to describe inequalities in health outcomes across populations.47 48 There is evidence that these aggregate measures are good proxies for individual deprivation, have similar performance than individual-level SES measures and represent a low risk of ecological bias.49 Furthermore, we did not use area-level data to impute individual values in the study cohort but rather used individual maternal postal codes to assign cohort members to a dissemination area that shared particular features from a census perspective. Since both the exposure (maternal postal code) and outcome were measured at the individual level, the risk of ecologic fallacy is likely low.47

We used area-level data from the 2006 Canadian census for the calculation of the SES index. The method assumed no changes in area-level deprivation between 2006 and 2012 and therefore, potential misclassification of the SES may occur. Other studies using area-level deprivation measures have attempted to quantify changes in SES categories over time and have assumed that SES remains relatively stable over time,30 46 and that census-based measures of deprivation can be used in larger comparative studies across decades without loss of continuity over time.50 51

There is concern that area-based SES indexes are likely sensitive to urban−rural differences and that variables that capture deprivation and SES in cities may not perform well in rural areas. Despite these conceptual constraints, there is evidence from other studies showing that available deprivation indexes can be used legitimately in both settings, supporting the hypothesis that the underlying relationship between area-level SES and health gradients is the same in rural and urban areas.35 52 53

Future perspectives

Studies about socioeconomic gradients in health provide a way to identify gaps that characterise the health (or ill health) of socioeconomic groups,7 helping health authorities to evaluate the performance of healthcare systems, policies and interventions.54 Our evaluation of inequalities in perinatal health and influential factors across urban and rural areas has important implications. First, improving accessibility and adequate and high-quality prenatal care, especially for the lower SES groups, may reduce socioeconomic-related inequalities in maternal and perinatal health in both rural and urban areas. Particularly, the most disadvantaged groups are concentrated in rural areas in terms of their perinatal outcomes. Interventions targeting these rural populations in terms of increasing perinatal health and income can be a cost-effective tool to tackle these health inequalities.

Conclusion

In summary, using a concentration index approach, we identified SES-related inequalities in the distribution of adverse birth outcomes and related maternal factors, with a major impact in rural areas. Future research is needed on the underlying mechanisms driving the observed different patterns of socioeconomic inequalities in health distribution across the rural–urban spectrum.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @MariaBOspina, @aosornio

Contributors: MO participated in investigation, conceptualisation/design, methodology, drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. ARO-V participated in funding acquisition, resources, conceptualisation/design, supervision, critically review/edit the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. CCN participated in conceptualisation/design, methodology, geographic analysis and approved the final version of the manuscript. SC participated in conceptualisation/design, resources (health data provider), critically review/edit the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. MK participated in funding acquisition, conceptualisation/design, supervision, critically review/edit the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. KA participated in funding acquisition, conceptualisation/design, supervision, critically review/edit the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. JS-L participated in funding acquisition, conceptualisation/design, database management, statistical analysis, critically review/edit the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC): a CIHR/NSERC Collaborative Health Research Programme (FRN: 127789); CONACyT Mexico; and the Emerging Research Team Grant, University of Alberta. Data provider: Alberta Perinatal Health Programme. This study is part of the Data Mining and Neonatal Outcomes project (DoMINO-project: Team members in: https://sites.google.com/a/ualberta.ca/domino/home/team-members). MO is funded by the generous supporters of the Lois Hole Hospital for Women through the Women and Children’s Health Research Institute.

Disclaimer: The study sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; and in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study received ethics approval from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The custodian of the data is the provincial program called Alberta Perinatal Health Program. After they review our research protocol, we obtained anonymised data exclusively for this work without authorisation to share them or to do secondary analysis. Births and maternal data are available upon formal request to the Alberta Perinatal Health Program. The data related to the SES index are available from Policy Wise (http://www.policywise.com).

References

- 1. Beck S, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: a systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:31–8. 10.2471/BLT.08.062554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Black RE. Global prevalence of small for gestational age births. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser 2015;81:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim SY, Sharma AJ, Sappenfield W, et al. Association of maternal body mass index, excessive weight gain, and gestational diabetes mellitus with Large-for-Gestational-Age births. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:737–44. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, et al. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health 2013;10:S2 10.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. social determinants of health discussion paper 2 (Policy and Practice). Geneva: WHO, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, et al. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:61–73. 10.1056/NEJMra0708473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keyes KM, Galea S. Population health science. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8. McCartney G, Collins C, Mackenzie M. What (or who) causes health inequalities: theories, evidence and implications? Health Policy 2013;113:221–7. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marmot M, Bell R. Social inequalities in health: a proper concern of epidemiology. Ann Epidemiol 2016;26:238–40. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Metcalfe A, Lail P, Ghali WA, et al. The association between neighbourhoods and adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of multi-level studies. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2011;25:236–45. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01192.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Amjad S, MacDonald I, Chambers T, et al. Social determinants of health and adverse maternal and birth outcomes in adolescent pregnancies: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2019;33:88–99. 10.1111/ppe.12529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blumenshine P, Egerter S, Barclay CJ, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:263 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim D, Saada A. The social determinants of infant mortality and birth outcomes in Western developed nations: a cross-country systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10:2296–335. 10.3390/ijerph10062296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kent ST, McClure LA, Zaitchik BF, et al. Area-level risk factors for adverse birth outcomes: trends in urban and rural settings. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:129 10.1186/1471-2393-13-129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Freudenberg N, Galea S, Vlahov D. Beyond urban penalty and urban sprawl: back to living conditions as the focus of urban health. J Community Health 2005;30:1–11. 10.1007/s10900-004-6091-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vlahov D, Freudenberg N, Proietti F, et al. Urban as a determinant of health. J Urban Health 2007;84:16–26. 10.1007/s11524-007-9169-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vlahov D, Galea S, Gibble E, et al. Perspectives on urban conditions and population health. Cad Saúde Pública 2005;21:949–57. 10.1590/S0102-311X2005000300031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luo Z-C, Wilkins R. Degree of rural isolation and birth outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2008;22:341–9. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00938.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abdel-Latif ME, et al. Does rural or urban residence make a difference to neonatal outcome in premature birth? A regional study in Australia. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2006;91:F256 10.1136/adc.2005.090670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lisonkova S, Sheps SB, Janssen PA, et al. Birth outcomes among older mothers in rural versus urban areas: a Residence-Based approach. J Rural Health 2011;27:211–9. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health 2008;98:216–21. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Costa-Font J, Hernández-Quevedo C. Measuring inequalities in health: what do we know? what do we need to know? Health Policy 2012;106:195–206. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wagstaff A, Paci P, van Doorslaer E. On the measurement of inequalities in health. Soc Sci Med 1991;33:545–57. 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90212-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Serrano-Lomelin J, Nielsen CC, Jabbar MSM, et al. Interdisciplinary-driven hypotheses on spatial associations of mixtures of industrial air pollutants with adverse birth outcomes. Environ Int 2019;131:104972 10.1016/j.envint.2019.104972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Statistics Canada Census profile, 2016 census, 2017. Available: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E [Accessed 23 Nov 2017].

- 26. Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, et al. A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics 2001;108:e35 10.1542/peds.108.2.e35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Statistics Canada Geo suite, 2006. Available: https://geosuite.statcan.gc.ca/geosuite/en/index [Accessed 02 Feb 2017].

- 28. Statistics Canada 2006 census dictionary, 2006. Available: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/ref/dict/index-eng.cfm [Accessed 06 May 2017].

- 29. Statistics Canada Census-Boundary files: reference guide, 2007. Available: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/geo/ref/2006/92-160-072305/92-160-0723052006003-eng.htm [Accessed 06/05, 2017].

- 30. Chan E, Serrano J, Chen L, et al. Development of a Canadian socioeconomic status index for the study of health outcomes related to environmental pollution. BMC Public Health 2015;15:714 10.1186/s12889-015-1992-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Borrell LN, Rodriguez-Alvarez E, Savitz DA, et al. Parental race/ethnicity and adverse birth outcomes in New York City: 2000–2010. Am J Public Health 2016;106:1491–7. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Regidor E. Measures of health inequalities: Part 2. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:900–3. 10.1136/jech.2004.023036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Erreygers G, Van Ourti T. Measuring socioeconomic inequality in health, health care and health financing by means of rank-dependent indices: a recipe for good practice. J Health Econ 2011;30:685–94. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Neudorf C, Fuller D, Cushon J, et al. An analytic approach for describing and prioritizing health inequalities at the local level in Canada: a descriptive study. CMAJ Open 2015;3:E366–72. 10.9778/cmajo.20150049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bertin M, Viel J-F, Monfort C, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes in urban and rural contexts: a French mother-child cohort. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2015;29:426–35. 10.1111/ppe.12208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Amjad S, Chandra S, Osornio-Vargas A, et al. Maternal area of residence, socioeconomic status, and risk of adverse maternal and birth outcomes in adolescent mothers. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2019;41:1752–9. 10.1016/j.jogc.2019.02.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lisonkova S, Haslam MD, Dahlgren L, et al. Maternal morbidity and perinatal outcomes among women in rural versus urban areas. Can Med Assoc J 2016;188:E456–65. 10.1503/cmaj.151382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grzybowski S, Stoll K, Kornelsen J. Distance matters: a population based study examining access to maternity services for rural women. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:147 10.1186/1472-6963-11-147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Combier E, Charreire H, Le Vaillant M, et al. Perinatal health inequalities and accessibility of maternity services in a rural French region: closing maternity units in Burgundy. Health Place 2013;24:225–33. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mantwill S, Monestel-Umaña S, Schulz PJ. The relationship between health literacy and health disparities: a systematic review. PLoS One 2015;10:e0145455 10.1371/journal.pone.0145455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lu Y, Qin L. Healthy migrant and salmon bias hypotheses: a study of health and internal migration in China. Soc Sci Med 2014;102:41–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hajizadeh M, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Socioeconomic gradient in health in Canada: is the gap widening or narrowing? Health Policy 2016;120:1040–50. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Reading R, Raybould S, Jarvis S. Deprivation, low birth weight, and children's height: a comparison between rural and urban areas. BMJ 1993;307:1458–62. 10.1136/bmj.307.6917.1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gorber SC, Schofield-Hurwitz S, Hardt J, et al. The accuracy of self-reported smoking: a systematic review of the relationship between self-reported and cotinine-assessed smoking status. Nicotine Tobacco Res 2009;11:12–24. 10.1093/ntr/ntn010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Galobardes B, Lynch J, Smith GD. Measuring socioeconomic position in health research. Br Med Bull 2007;81-82:21–37. 10.1093/bmb/ldm001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fuller D, Neudorf J, Lockhart S, et al. Individual- and area-level socioeconomic inequalities in diabetes mellitus in Saskatchewan between 2007 and 2012: a cross-sectional analysis. CMAJ Open 2019;7:E33–9. 10.9778/cmajo.20180042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Subramanian SV, Chen JT, Rehkopf DH, et al. Comparing Individual- and area-based socioeconomic measures for the surveillance of health disparities: a multilevel analysis of Massachusetts births, 1989–1991. Am J Epidemiol 2006;164:823–34. 10.1093/aje/kwj313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Choosing area based socioeconomic measures to monitor social inequalities in low birth weight and childhood lead poisoning: the public health disparities Geocoding project (US). J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:186–99. 10.1136/jech.57.3.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bryere J, Pornet C, Copin N, et al. Assessment of the ecological bias of seven aggregate social deprivation indices. BMC Public Health 2017;17:86 10.1186/s12889-016-4007-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Allik M, Brown D, Dundas R, et al. Developing a new small-area measure of deprivation using 2001 and 2011 census data from Scotland. Health Place 2016;39:122–30. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Marí-Dell'Olmo M, Gotsens M, Palència L, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in cause-specific mortality in 15 European cities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:432–41. 10.1136/jech-2014-204312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pampalon R, Hamel D, Gamache P. Health inequalities in urban and rural Canada: comparing inequalities in survival according to an individual and area-based deprivation index. Health Place 2010;16:416–20. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bertin M, Chevrier C, Pelé F, et al. Can a deprivation index be used legitimately over both urban and rural areas? Int J Health Geogr 2014;13:22 10.1186/1476-072X-13-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yaya S, Uthman OA, Ekholuenetale M, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in the risk factors of noncommunicable diseases among women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan Africa: a multi-country analysis of survey data. Front Public Health 2018;6:307 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.