Abstract

Study objectives:

While anxiety rates are alarmingly high in short sleeping insomniacs, the relationship between insomnia and anxiety symptoms has not been extensively studied, especially in comparison to the relationship between insomnia and depressive symptoms. Using residency training as a naturalistic stress exposure, we prospectively assessed the role of sleep disturbance and duration on anxiety-risk in response to stress.

Methods:

Web-based survey data from 1336 first-year training physicians (interns) prior to and then quarterly across medical internship. Using mixed effects modeling, we examined how pre-internship sleep disturbance and internship sleep duration predicted symptoms of anxiety, using an established tool for quantifying symptom severity in generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

Results:

Pre-internship poor sleepers are at more than twice the odds of having short sleep (≤6 h) during internship as good sleepers (OR = 2.38, 95% CI = 1.61, 3.57). Poor sleepers were also at twice the odds for screening positive for probable GAD diagnosis (OR = 2.08, 95% CI = 1.26, 3.45). Notably, sleep onset insomnia strongly predicted anxiety development under stress (OR = 3.55, 95% CI = 1.49, 8.45). During internship, short sleep associated with concurrent anxiety symptoms (b = −0.26, 95% CI = −0.38, −0.14) and predicted future anxiety symptoms even more strongly (b = −0.39, 95% CI = −0.76, −0.03).

Conclusions:

Poor sleepers, particularly those with sleep onset insomnia symptoms, are vulnerable to short sleep and GAD anxiety and worry during chronic stress.

Keywords: Insomnia, Anxiety, Worry, Stress, Residents, Physicians

1. Introduction

Clinical anxiety is the most highly prevalent form of mental illness in the US [1,2] with enormous personal and financial costs [3,4]. Identifying individuals at risk for developing anxiety disorders prior to disease onset could foster preventive or early interventions and reduce the public health burden. A burgeoning literature identifies problematic sleep as a common precursor to mental illness, particularly depression [5-9], and growing evidence suggests that concomitant short sleep may augment the pathogenicity of sleep disturbance during stress [10-13]. As much of the work on psychiatric illness in the context of poor sleep has centered on depression, anxiety is an often overlooked epidemic in insomnia [10,14,15]. Recent epidemiological data suggest that individuals with both short sleep and insomnia (which are distinct types of sleep disruption [10,11,16]) experience more anxiety symptoms than those with short sleep or insomnia alone [12,17].

GAD is a common and disabling form of clinical anxiety that affects 9.0% of US adults across the lifespan [18], and typically runs a chronic course with symptomatic ebbs and flows [19]. Its defining characteristic is persistent and excessive worry, which involves recurrent and intrusive thoughts about potential negative outcomes signaled by perceived threats [20,21]. Worrying and perseverating on stressors precludes adaptive emotion regulation, thereby giving rise to and prolonging negative and anxious affect states [22-24]. Although GAD patients are known to sleep poorly (sleep disturbance is one of its diagnostic criteria), whether poor sleep precedes anxiety development or is an expression or consequence of its presence is unknown.

Possibly linking sleep disturbance to GAD, cognitive arousal—dincluding worry and other forms—is a key component in current models of insomnia [14,25-29]. However, causality may run in both directions in creating a link between sleep disturbance and GAD. Individuals who struggle to initiate and maintain sleep may be especially vulnerable to worry and to GAD by extension, given that the inability to sleep creates a period of solitary and unstructured time in bed at night. Potentially compounding this anxiogenic cognitive environment, poor sleepers with short sleep duration (eg, ≤6 h/night [30]) exhibit poorer ability to regulate stress than those with normal sleep duration [10,31]. A substantial portion of cognitive arousal in poor sleepers occurs during the presleep period [25,32], thus poor sleepers presenting primarily with sleep onset insomnia symptoms may be especially prone to nocturnal pathological worry when stressed. Despite evidence suggesting that individuals with short and disturbed sleep are highly vulnerable to stress and to psychopathology, anxiety remains understudied as a consequence of sleep problems. No prospective research to-date has examined the independent and combined effects of sleep disturbance and short sleep on anxiety development during chronic stress.

Stress-diathesis research faces many logistical challenges including reliance on retrospective assessments and substantial variation in the type and intensity of stress between subjects. Medical internship is a rare situation where we can prospectively predict that a large cohort of individuals will experience dramatic increases in stress, thus offering a unique paradigm to study stress-related risk factors in mental illness. Indeed, medical internship year is a difficult transition marked by high stress [33,34], long workdays and burnout [35,36], and inadequate sleep [37-42]. Prior studies have shown these factors to create an environment fertile for developing psychiatric illness [13,43-47]. Significantly, nearly one-fifth of training physicians report significant sleep disturbance complaints in the months preceding intern year, and these disturbed sleepers are at more than twice the odds to develop depression during internship than good sleepers [39]. Further, medical interns report high rates of short sleep [38-40], which has been shown to increase depression-risk [13,40]. However, it is presently unclear whether both short and disturbed sleep confer stress-related vulnerabilities to other debilitating forms of psychopathology, like GAD.

The present study investigated whether sleep disturbance and short sleep predict GAD symptoms during stress. We collected sleep and anxiety data from training physicians across the US prior to and then quarterly across the intern year. Leveraging internship as a naturalistic stress exposure, we prospectively characterized changes in sleep and anxiety in response to stress. We hypothesized that sleep disturbance and short sleep (≤6 h/night) would predict higher anxiety under stress. As cognitive arousal among poor sleepers often dominates the presleep period, we also hypothesized that subjects reporting nocturnal symptoms of sleep onset insomnia would be particularly vulnerable to anxiety during stress.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The Intern Health Study is a multi-site prospective cohort study that assesses stress, mood, sleep, and work-related behaviors before and across the internship year. The study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board and all subjects provided informed consent. Trainees were recruited via email with 1342 interns (58% participation rate) in 10 specialties across 33 institutions agreeing to participate in the study. Of these subjects, 1336 reported anxiety symptoms (our primary outcome variable, measured quarterly) at least once prior to and during intern year (Pre-internship n = 1326; Q1 n = 996; Q2 n = 985; Q3 n = 934; Q4 n = 908).

2.2. Procedure

Data were collected using web-delivered surveys hosted by Qualtrics. Procedures have been outlined in detail elsewhere [43,48]. Briefly, participants were recruited after internship match and those enrolled were emailed web-based surveys on mood, health behaviors, stress, internship factors, and demographics at five time-points: 1–2 months prior to internship (pre-internship), then quarterly across intern year (at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months).

2.3. Measures

Age, gender, and medical specialty were collected prior to internship start, along with measures of anxiety, depression, and sleep. Symptoms of GAD were measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item [49] scale (GAD-7), a brief self-report measure of symptom severity in GAD (including worry, restlessness, and difficulty relaxing). Scores ≥10 were interpreted as screening positive for GAD. Validation research has shown this ≥10 cut-point to boast good sensitivity (89%) and specificity (82%) for detecting clinical GAD [49]. Symptoms of depression were measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [50], a 9-item self-report measure of depressive symptom severity. The PHQ-9 has 88% sensitivity and 93% specificity for detecting clinical depression, with scores ≥10 interpreted as screening positive for depression [50]. The GAD-7 and the PHQ-9 were repeated quarterly over the internship year.

The 19-item Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [51] (PSQI) was used prior to internship to assess sleep quality based on self-reported sleep duration, sleep onset latency, sleep efficiency, subjective sleep quality, and sleep interfering-behaviors. A global cutoff score of >5 yields good sensitivity (90%) and specificity (87%) in distinguishing good from poor sleepers. Higher scores on the PSQI indicate greater sleep disturbance. Estimated sleep latency was derived from PSQI item #2 (‘How long in minutes has it taken you to fall asleep each night?’), with latencies >30 m identified as problematic per established quantitative cutoffs [52]. Sleep onset insomnia was assessed with PSQI item #5a (‘During the past month, how often have you had trouble sleeping because you cannot get to sleep within 30 min’), with responses of ‘Three or more times a week’ indicating the presence of nocturnal sleep onset insomnia symptoms. Responses to PSQI item #4a (‘During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night?’) were used to estimate pre-internship sleep duration.

Sleep duration was also assessed quarterly during internship, along with the GAD-7 and PHQ-9, using the question: “On average, how many hours per day have you slept per night over the past week?” Individuals who reported sleeping a nightly average of ≤6 h were identified as short sleepers per empirically derived cutoffs for neurobehavioral dysfunction [53]. Weekly work hours were also estimated quarterly in response to the question: “On average, how many hours have you worked in the past week?”

2.4. Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS 24 and STATA SE 15.1, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. First, we compared non-anxious interns (those who never screened positive for anxiety) and anxious interns (screened positive at any time prior to or during internship) on demographics, internship factors, and mood and sleep parameters to examine differences in group characteristics. To test our specific hypotheses, linear mixed effects modeling with random intercepts was used to estimate internship anxiety symptoms (as a within-subjects factor) as predicted by pre-internship sleep disturbance (between-subjects factor) and internship sleep duration (within-subjects factor), while controlling for demographic and internship factors such as gender, internship work hours (within-subjects factor), internship depression symptoms (between-subjects factor), and time (as repeated measures during internship showed significant change over time). Mixed effects logistic regression was used when predicting anxiety status (negative vs positive screen) during intern year. Lastly, we used χ2 analyses and dummy coded logistic regression to compare odds for developing new onset anxiety among different sleep classifications based on pre-internship sleep disturbance, pre-internship sleep onset insomnia symptoms, and internship sleep duration.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and sample characteristics

Consistent with internship as a naturalistic stress exposure that increases stress-related anxiety symptoms, rates of positive GAD screens increased from 3.2% in the pre-internship period to 10.4–15.3% during intern year (see Table 1 for quarterly descriptives). Prior to testing hypotheses, we compared demographics and characteristics across two groups: interns who never screened positive for clinical anxiety prior to or during internship vs those who screened positive for clinical anxiety at any time prior to or during internship. Overall, anxious interns were at greater odds of being female and endorsed greater sleep disturbance, shorter sleep, greater sleep aid use, and more depression than non-anxious interns; see Table 1 for full results.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n = 1336).

| Non-anxious interns (n = 1089) | Anxious interns (n = 247) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M ± SD) | 27.49 y ± 2.82 | 27.73 y ± 2.81 | t = 1.20, p = 0.23 |

| Female (n, %) | 487/1078; 45.2% | 113/184; 61.4% | χ2 = 16.61***, RR = 1.36 |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 61.8% | 61.2% | ns |

| Black | 3.9% | 2.9% | ns |

| Asian | 21.8% | 24.5% | ns |

| Latino | 3.1% | 3.3% | n/a |

| Native American | 0.0% | 0.4% | n/a |

| Pacific Islander | 0.1% | 0.4% | ns |

| Multi-racial | 4.6% | 3.3% | ns |

| “Other” | 4.7% | 4.1% | ns |

| Specialty (%) | |||

| Internal Medicine | 35.9% | 32.4% | ns |

| Surgery | 11.8% | 11.3% | ns |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 4.0% | 5.7% | RR = 1.43, p < 0.05 |

| Pediatrics | 9.9% | 15.8% | ns |

| Psychiatry | 5.7% | 6.9% | ns |

| Emergency Medicine | 6.8% | 4.9% | ns |

| Medicine/Pediatrics | 2.2% | 2.0% | ns |

| Family Practice | 5.9% | 4.5% | ns |

| “Other” | 16.9% | 15.0% | ns |

| Transitional | 1.0% | 1.6% | n/a |

| Anxiety (M ± SD, prevalence) | |||

| Pre-internship | 1.62 ± 1.94 | 5.40 ± 4.50 | t = 19.06***, d = 1.09; 3.2% |

| 3 months | 2.72 ± 2.45 | 10.96 ± 4.02 | t = 33.65***, d = 2.48; 11.3% |

| 6 months | 2.66 ± 2.41 | 10.26 ± 4.85 | t = 28.83***, d = 1.98; 11.9% |

| 9 months | 2.72 ± 2.45 | 9.57 ± 5.31 | t = 23.71***, d = 1.66; 10.4% |

| 12 months | 3.49 ± 3.37 | 10.27 ± 4.99 | t = 19.66***, d = 1.59; 15.3% |

| Sleep | |||

| Pre-internship | |||

| Disturbance; % poor | 3.45 ± 2.40; 16.6% | 4.82 ± 3.16; 36.1% | t = 7.42***, d = 0.49, RR = 2.17 |

| Latency; % > 30 m | 16.03 m ± 12.05; 5.7% | 18.89 m ± 14.49; 12.2% | t = 3.19**, d = 0.21, RR = 2.14 |

| Sleep onset insomnia n,% | 48/1020, 4.5% | 30/243, 12.3% | χ2 = 21.81***, RR = 2.73 |

| Duration; % short (≤6 h) | 7.35 h ± 1.15; 20.4% | 7.16 h ± 1.28; 28.2% | t = −1.95*, d = 0.14, RR = 1.38 |

| Sleep aid use | 12.7% | 24.0% | χ2 = 19.91, p < 0.001 |

| Within-internship | |||

| Duration at 3 months, % short | 6.44 h ± 0.94; 47.1% | 6.21 h ± 0.97; 54.5% | t = −3.16**, d = 0.24, RR = 1.16 |

| Duration at 6 months, % short | 6.49 h ± 0.93; 47.1% | 6.35 h ± 1.09; 53.3% | t = 2.00*, d = 0.14, RR = 1.13 |

| Duration at 9 months, % short | 6.50 h ± 1.10; 47.1% | 6.39 h ± 1.10; 50.3% | t = −1.28, p = 0.20 |

| Duration at 12 months, % short | 6.50 h ± 0.92; 49.0% | 6.43 h ± 1.11; 53.5% | t = −0.84, p = 0.40 |

| Depression (M ± SD) | |||

| Pre-internship | 2.12 ± 2.48 | 4.63 ± 4.07 | t = 11.41***, d = 0.75 |

| 3 months | 4.47 ± 3.39 | 10.68 ± 4.98 | t = 18.98***, d = 1.46 |

| 6 months | 4.60 ± 3.55 | 10.51 ± 5.23 | t = 17.15***, d = 1.32 |

| 9 months | 4.69 ± 3.57 | 9.77 ± 5.37 | t = 13.82***, d = 1.11 |

| 12 months | 4.50 ± 3.80 | 9.92 ± 5.05 | t = 14.38***, d = 1.21 |

| Work hours (M ± SD) | |||

| 3 months | 65.52 h ± 16.86 | 71.45 h ± 12.94 | t = 4.13***, d = 0.39 |

| 6 months | 65.37 h ± 17.30 | 65.93 h ± 19.62 | t = 0.36, p = 0.72 |

| 9 months | 64.67 h ± 17.00 | 64.90 h ± 18.89 | t = 0.15, p = 0.88 |

| 12 months | 62.53 h ± 18.62 | 63.07 h ± 21.12 | t = 30, p = 0.76 |

Non-anxious interns never screened positive for anxiety before or during internship. Anxious interns screened positive for anxiety at any time prior to or during internship. Pre-internship sleep assessed by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Internship sleep and work hours were self-reported. Sleep onset insomnia indicated by endorsing ‘Cannot get to sleep within 30 min three or more times a week’ (PSQI item #5a, ‘Cannot get to sleep within 30 min’ on ≥3 days/week). Anxiety assessed by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale. Depression assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale. M = mean. SD = standard deviation. t = t-statistic. p = significance value. d = Cohen's d. χ2 = chi-square. RR = relative risk.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

ns = non-significant difference in column proportions.

n/a = insufficient observations in at least one cell to compare column proportions.

3.2. Sleep, stress, and anxiety

We first examined whether pre-internship sleep quality predicts duration of sleep obtained during internship. Logistic mixed modeling showed that pre-internship poor sleepers had more than twice the odds as good sleepers of developing short sleep (b= 0.87, z = −4.41, OR−1 2.38, 95% CI = 1.61–3.57), even while controlling for gender (p = 0.17), pre-internship anxiety status (p = 0.61), work hours (OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.08–1.10), and time (p = 0.61).

We next assessed whether pre-internship factors predict anxiety under internship stress using linear mixed modeling (see Table 2, Model 1). Sleep disturbance (b = 0.09, p = 0.04), female gender (b = 0.86, p < 0.001), and pre-internship anxiety (b = 0.47, p < 0.001) but not pre-internship depression (p = 0.09) predicted GAD-7 anxiety symptoms during internship.

Table 2.

Anxiety during internship as estimated by sleep disturbance.

| b (SE) | 95% CI | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Pre-internship factors predicting internship anxiety (obs = 3536) | ||||

| Pre-internship Predictors | ||||

| Age | 0.04 (0.04) | −0.03, 0.11 | 1.19 | 0.24 |

| Female gender | 0.86 (0.19) | 0.48, 1.23 | 4.47 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 0.47 (0.04) | 0.39, 0.55 | 11.56 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 0.07 (0.04) | −0.01, 0.16 | 1.67 | 0.09 |

| Sleep disturbance | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.00, 0.17 | 2.01 | 0.04 |

| Internship Predictors | ||||

| Time | 0.19 (0.05) | 0.10, 0.27 | 4.55 | <0.001 |

| Model 2: Pre-internship & internship factors predicting anxiety (obs = 3529) | ||||

| Pre-Internship Predictors | ||||

| Age | 0.02 (0.03) | −0.03, 0.07 | 0.73 | 0.47 |

| Female gender | 0.30 (0.13) | 0.04, 0.56 | 2.25 | 0.03 |

| Anxiety | 0.34 (0.03) | 0.29, 0.40 | 12.02 | <0.001 |

| Depression | −0.17 (0.03) | −0.23, −0.11 | −5.34 | <0.001 |

| Sleep disturbance | −0.02 (0.03) | −0.08, 0.04 | −0.76 | 0.45 |

| Internship Predictors | ||||

| Time | 0.24 (0.04) | 0.16, 0.31 | 5.98 | <0.001 |

| Sleep duration | −0.26 (0.06) | −0.38, −0.14 | −4.33 | <0.001 |

| Work hours | 0.02 (0.00) | 0.02, 0.03 | 7.62 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 0.66 (0.02) | 0.62, 0.70 | 32.50 | <0.001 |

| Model 3: Short and disturbed sleep predicting intern anxiety status (obs = 3529) | ||||

| Pre-Internship Predictors | OR; 95% CI | |||

| Age | 0.01 (0.04) | – | 0.29 | 0.77 |

| Female gender | 0.72 (0.24) | 2.05; 1.30, 3.25 | 3.08 | <0.001 |

| Anxious vs non-anxious | 2.02 (0.58) | 7.55; 2.44, 23.36 | 3.51 | <0.001 |

| Depressed vs non-depressed | 1.41 (0.57) | 4.10; 1.34, 12.54 | 2.48 | 0.01 |

| Poor vs good sleep | 0.73 (0.26) | 2.08; 1.26, 3.45 | 2.85 | <0.01 |

| Internship Predictors | ||||

| Time | 0.19 (0.06) | 1.21; 1.07, 1.37 | 3.07 | <0.01 |

| Short sleep (≤6 h) | −0.84 (0.21) | 2.33*; 1.54, 3.57 | −3.99 | <0.001 |

| Work hours (>70 h) | 0.02 (0.04) | – | 0.61 | 0.55 |

| Depressed vs non-depressed | 0.30 (0.06) | 1.35; 1.21, 1.50 | 5.42 | <0.001 |

| Model 4: Internship sleep duration predicting future anxiety (obs =2281) | ||||

| Pre-Internship Predictors | ||||

| Age | 0.01 (0.02) | −0.05, 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.86 |

| Female gender | 0.19 (0.16) | −0.11, 0.50 | 1.24 | 0.22 |

| Anxiety | 0.80 (0.37) | 0.07, 1.53 | 2.16 | 0.03 |

| Depression | 0.55 (0.34) | −0.13, 1.23 | 1.58 | 0.11 |

| Sleep disturbance | 0.22 (0.17) | −0.11, 0.56 | 1.32 | 0.19 |

| Internship Predictors | ||||

| Time | 0.18 (0.09) | −0.00, 0.36 | 1.93 | 0.05 |

| Sleep duration, lagged | −0.39 (0.19) | −0.76, −0.03 | −2.12 | 0.03 |

| Work hours, lagged | 0.00 (0.06) | −0.11, 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.97 |

| Anxiety, lagged | 2.32 (0.21) | 1.92, 2.72 | 11.28 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 0.17 (0.03) | 0.10, 0.23 | 5.09 | <0.001 |

| Model 5: Anxiety symptoms predicting future sleep duration (obs = 2305) | ||||

| Pre-Internship Predictors | ||||

| Age | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02, 0.01 | −0.90 | 0.37 |

| Female gender | 0.07 (0.04) | −0.00, 0.15 | 1.89 | 0.06 |

| Anxiety | 0.00 (0.01) | −0.02, 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.96 |

| Depression | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.00, 0.04 | 2.32 | 0.02 |

| Sleep disturbance | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.03, −0.00 | −2.01 | 0.04 |

| Internship Predictors | ||||

| Time | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.05, 0.04 | −0.31 | 0.75 |

| Anxiety, lagged | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.02, 0.04 | 4.77 | <0.001 |

| Work hours, lagged | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.00, 0.00 | 1.10 | 0.27 |

| Sleep duration, lagged | 0.41 (0.02) | 0.35, 0.45 | 17.12 | <0.001 |

| Depression | −0.06 (0.01) | −0.07, −0.05 | −8.12 | <0.001 |

| Model 6: Insomnia and short sleep predicting intern anxiety status (obs 3553) | ||||

| Pre-Internship Predictors | OR; 95% CI | |||

| Age | 0.00 (0.04) | – | 0.10 | 0.92 |

| Female gender | 0.71 (0.23) | 2.03; 1.29, 3.20 | 3.04 | <0.01 |

| Anxious vs non-anxious | 2.20 (0.57) | 9.06; 2.94, 27.93 | 3.84 | <0.001 |

| Depressed vs non-depressed | 1.61 (0.56) | 5.02; 1.68, 15.15 | 2.87 | <0.01 |

| Sleep onset insomnia | 1.27 (0.44) | 3.55; 1.49, 8.45 | 2.86 | <0.01 |

| Short sleep (≤6 h) | −0.05 (0.28) | – | −0.16 | 0.88 |

| Internship Predictors | ||||

| Time | 0.19 (0.21) | 1.20; 1.07, 1.36 | 3.00 | <0.01 |

| Short sleep (≤6 h) | −0.92 (0.21) | 2.50*; 1.67, 3.70 | −4.38 | <0.001 |

| Work hours (>70 h) | 0.03 (0.04) | – | 0.64 | 0.52 |

| Depressed vs non-depressed | 0.29 (0.06) | 1.34; 1.20, 1.50 | 5.34 | <0.001 |

n = sample size. b = unstandardized regression coefficient. SE = standard error. CI = confidence interval. z = z-statistic. p = significance value. χ2 = chi-square. obs = number of observations in model. OR = Odds Ratio, not reported for parameters with p-values > 0.10.

= OR inversed to improve interpretability. Pre-Internship Predictors regard between-subjects effects, whereas Internship Predictors concern within-subjects effects. Anxiety measured by the Generalized Anxiety Disorders 7-item scale. Depression measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale. Pre-internship sleep latency and duration measured by items #2 and #4a of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), respectively. Sleep onset insomnia indicated by endorsing ‘Cannot get to sleep within 30 min three or more times a week’ (PSQI item #5a, ‘Cannot get to sleep within 30 min’ on ≥ 3 days/week). Time measured quarterly. Internship sleep duration and work hours were estimated by subjects.

We then identified within-internship factors predictive of internship anxiety (Table 2, Model 2). Linear mixed modeling showed that shorter sleep was linked to greater anxiety within the internship year (b = −0.26, p < 0.001). Importantly, the relationship between internship sleep duration and anxiety remained significant even after controlling for internship depression (b = 0.66, p < 0.001), work hours (b = 0.02, p < 0.001), and pre-internship factors. A parallel logistic mixed effects model with GAD status (negative vs positive screen) as the outcome showed that pre-internship poor sleepers were at two-fold greater odds for screening positive for GAD (OR = 2.08, p < 0.01; Table 2, Model 3) and that interns more than doubled their anxiety-risk when sleeping ≤ 6 h per night during internship (OR−1 = 2.33, p < 0.001).

After finding that short sleep duration and anxiety were associated during internship, we tested directionality by lagging within-internship predictors in our mixed effects models. We first found that shorter sleep during internship predicts greater anxiety three months later (b = −0.39, p = 0.03; Table 2, Model 4). Importantly, this relationship was not accounted for by lagged values for work hours (p = 0.97) or anxiety (b = 2.32, p < 0.001). In a follow-up model examining the opposite direction (Table 2, Model 5), we found that internship anxiety (b = 0.03, p < 0.001) predicted shorter sleep later during internship. Notably, the effect size of short sleep on future anxiety (b = 0.39) was considerably larger than the effect size of anxiety on future sleep (b = 0.03).

3.3. Sleep onset insomnia and short sleep duration: anxiety risk factors

Sleep onset insomnia is considered critical in linking sleep disturbance and anxiety during stress. To test anxiety-risk associated with sleep onset insomnia specifically, we ran a logistic mixed model estimating intern anxiety status as predicted by pre-internship sleep onset insomnia symptoms, while controlling for pre-internship short sleep, internship short sleep, and previously identified covariates (Table 2, Model 6). Training physicians with sleep onset insomnia prior to internship were at three-to-four-fold greater odds for screening positive for GAD than those with good sleep (OR = 3.55, 95% CI = 1.49, 8.45). Of note, short sleep during internship was also significant in the model (OR = 2.50, p < 0.001), whereas pre-internship short sleep was not (p = 0.88).

3.4. Rates of new onset anxiety: comparing sleep groups

Lastly, we evaluated rates of new onset anxiety during internship based on sleep classification. To examine new onset anxiety specifically, we included only subjects who did not meet the clinical cut-off for GAD prior to internship. Sleep disturbance and sleep onset insomnia were based on pre-internship PSQI, whereas short sleep classification here was based on average sleep duration reported during internship (minimum of two observations). Consistent with the mixed models, problematic sleepers with significant sleep disturbance, sleep onset insomnia symptoms, and short sleep duration were significantly more likely than good sleepers to newly reach clinical levels of anxiety symptom endorsement when under stress (see Table 3 for full results).

Table 3.

Rates of anxiety onset during internship based on sleep disturbance and duration.

| Anxiety rates | Model fit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never-anxious | Anxiety onset | Onset rates | ||

| Sleep disturbance | χ2 = 18.36, p < 0.001 | |||

| Good sleepers | 856 | 135 | 13.6% | |

| Poor sleepers | 170 | 57 | 25.1% | RR = 1.85 |

| Sleep duration | X2 = 7.16, p < 0.01 | |||

| Sufficient sleepers | 591 | 142 | 19.4% | |

| Short sleepers | 245 | 89 | 26.6% | RR = 1.37 |

| Sleep onset insomnia | X2 = 19.69, p < 0.001 | |||

| No insomnia | 1020 | 176 | 14.7% | |

| Insomniacs | 48 | 25 | 34.2% | RR = 2.33 |

| Sleep disturbance & short sleep | X2 = 24.82, p < 0.001 | |||

| Good and sufficient | 492 | 85 | 14.7% | |

| Good, but short | 191 | 46 | 19.4% | RR = – |

| Poor, but sufficient | 76 | 32 | 29.6% | RR = 2.01 |

| Poor and short sleep | 42 | 22 | 34.4% | RR = 2.34 |

| Sleep onset insomnia & short sleep | χ2 = 21.49, p < 0.001 | |||

| No insomnia, sufficient | 548 | 105 | 16.1% | |

| No insomnia, short | 221 | 58 | 20.8% | RR = – |

| Insomnia, sufficient | 20 | 12 | 37.5% | RR = 2.33 |

| Insomnia, short | 12 | 10 | 45.5% | RR = 2.83 |

Sample presented here only consists of subjects who screened negative for clinical anxiety prior to internship on the Generalized Anxiety Disorders 7-item scale. Never-anxious = never screened positive for anxiety during study. Anxiety onset = screened positive for anxiety at any time during internship. Sleep disturbance measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Good sleepers scored <5 on the PSQI, whereas Poor sleepers scored ≥5. Sleep duration was estimated by subjects during internship. Short sleepers reported an average sleep duration across intern year of ≤6 h/night with at least two observations, whereas Sufficient sleepers averaged >6 h/night with at least two observations. Sleep onset insomnia measured by PSQI item #5a ‘Cannot get to sleep within 30 min’ Subjects with insomnia reported inability to fall asleep within 30 m on ≥ 3 days/week for at least one month, whereas subjects with No insomnia did not. Onset rate = % of subjects in each sleep classification who screened positive for GAD at any time during internship. Model fit = χ2 analysis comparing sleep groups on anxiety rates. RR = relative risk, relative to the best sleepers in each sleep classification.

Because sleep disturbance/insomnia symptoms have synergistic effects with short sleep duration on morbidity, we also compared anxiety rates among good vs poor sleepers with and without short sleep (Table 3, Model: Sleep disturbance & short sleep). A dummy coded logistic regression model (good and sufficient sleepers as the reference group) showed that interns with poor quality but sufficient sleep (OR = 2.44, 95% CI = 1.52–3.91, p < 0.001) and interns with poor quality and short sleep (OR = 3.03, 95% CI = 1.72–5.33, p < 0.001) were at greater risk for anxiety than good sleepers with sufficient sleep. However, interns with good quality but short sleep were not at elevated anxiety-risk (OR = 1.39, 95% CI = 0.94–2.07, p = 0.10).

We repeated the above analysis to examine for synergistic effects between sleep onset insomnia symptoms and short sleep (Table 3 Model: Sleep onset insomnia & short sleep). Dummy coded logistic regression (subjects with sufficient sleep and no insomnia as reference group) showed that insomniacs with sufficient sleep (OR = 3.13, 95% CI = 1.49–6.60, p < 0.01) and insomniacs with short sleep (OR = 4.35, 95% CI = 1.83–10.33, p < 0.01) were both at elevated anxiety-risk.

4. Discussion

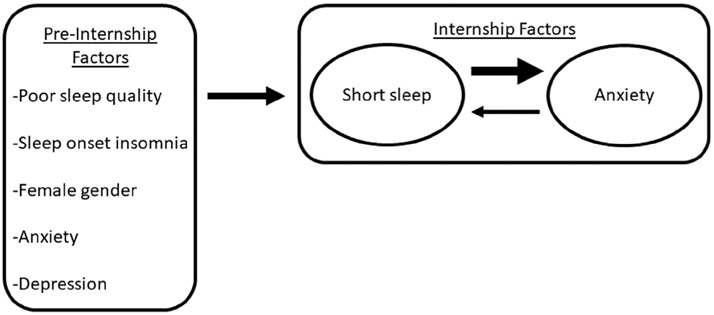

Leveraging medical internship as a natural stress exposure, this study examined whether sleep disturbance and short sleep predict symptoms of GAD during stress in 1336 training physicians. Physicians with significant sleep disturbance prior to internship were vulnerable to both short sleep and anxiety development during chronic stress exposure. Short sleep during internship further increased risk for anxiety. Difficulty falling asleep was the strongest predictor of stress-related vulnerability to anxiety, suggesting that individuals struggling to fall asleep may be especially vulnerable to worry in the context of stress. We found evidence for a bidirectional relationship between short sleep and GAD symptoms during internship (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Prospective associations among sleep problems, anxiety, and pre-internship factors.

Rates of positive GAD screens were consistently elevated among resident physicians with problematic sleep. Importantly, 45.5% of those who endorsed symptoms of sleep onset insomnia (sleep latency > 30 on ≥3 nights/week for at least one month) and habitual short sleep (≤6 h/night) screened positive for GAD during internship. These rates were nearly three times as high as individuals without either insomnia or short sleep (16.1%). These rates of clinical level GAD symptom endorsement are drastically higher than 12-month GAD prevalence rates of 3.1% in US adults [2], which highlights the magnitude of general risk for development of significant GAD symptoms during the chronic stress of medical internship and the markedly increased vulnerability for problematic sleepers.

These findings add support for sleep disturbance as a potential diathesis for GAD—a disorder flush with unmoored worries about perceived future threats and stressors—during chronic stress. Nocturnal wakefulness provides a breeding ground for worrisome thoughts, and nocturnal cognitive arousal is well-documented in disturbed sleep and insomnia [26,27,29,54-57]. Indeed, poor sleepers are more likely to engage in presleep negative repetitive thinking and to do so for longer durations than good sleepers [55]. Stress exposure may amplify this tendency for nocturnal cognitive arousal among those struggling to sleep by providing fodder for worry. Moreover, the inability to fall asleep can itself trigger negative schema (eg, helplessness) that provide additional content for presleep cognitive arousal [58]. Building on findings that sleep onset difficulties are often prodromal and presage more severe and debilitating forms of insomnia [59,60] and are linked to cognitive arousal and worry [61-63], our work adds further evidence implicating prolonged sleep latency as a key factor in stress vulnerability. By comparison, good sleepers may be resilient in the face of stress, as falling and staying asleep at night may serve as an adaptive reprieve from worrisome thoughts that dominate during the day.

Our results also lend support to the growing recognition that various dimensions of sleep-wake function independently and aggregately impact health [16]. A burgeoning literature highlights the synergistically detrimental effects of sleep disturbance (reduced efficiency) and objectively measured short sleep (reduced duration) on psychiatric illness and other morbidities [10,11,64-68]. In a recent epidemiological cross-sectional analysis on insomnia and short sleep, we found that insomniacs with short sleep endorse higher rates of anxiety than those with insomnia or short sleep alone [12]. Our data here expand on these findings by prospectively demonstrating that short sleep during stress may augment the influences of pre-existing sleep disturbance and insomnia on GAD symptom development in the context of stress. Consistent with our findings, others have shown that insomniacs who also had short sleep duration demonstrate greater encephalographic cortical activity during sleep than insomniacs with normal sleep duration [69]. This may reflect heightened vulnerability to stress-activated cognitive arousal intruding on and further disrupting efforts to sleep. The causal sequence here remains uncertain. Poor sleep may set the stage for symptom development in the context of stress, which then further undermines sleep. It may also reflect an underlying GAD-related vulnerability, with sleep onset insomnia as a predictive marker, and short sleep in the context of stress as a subsequent development that then fosters full expression of the disorder. It is necessary to emphasize here that objectively measured short sleep (via polysomnography or wearable technology) is ultimately critical for determining risk of adverse outcomes associated with sleep disturbance and insomnia. Future research is needed to replicate findings of the current study with objective sleep duration data to better understand the long-term consequences of insomnia symptoms and short sleep on prospective anxiety-risk.

Our data support the idea that sleep onset insomnia may be a marker of vulnerability, since it predicted later anxiety symptoms. Although our data indicate a bidirectional relationship between sleep duration and anxiety during chronic stress (which is consistent with prior research [70]), short sleep had a substantially larger impact on future anxiety, than vice versa. Notably, this finding has been demonstrated in an independent cohort in the Intern Health Study utilizing objective sleep data and daily mobile health monitoring [42]. Further work is needed to more precisely dissect the causal pathways here and to determine their relevance to GAD as a clinical disorder.

4.1. Limitations

Given that the sample consisted of training physicians, its demographics do not represent the broader US adult population. However, other literature on sleep disturbance, short sleep, and psychiatric illness in non-physician populations [10,11,71] suggests that our findings are not unique to this specialized sample, with the exception of prevalence rates which are elevated among interns. The GAD-7 has excellent diagnostic utility [49], but clinical interviews are necessary for accurate diagnosis of DSM-defined disorders. Similarly, collecting subjective ratings is an important aspect of sleep measurement, but optimal assessment would also include objective indicators (ie, polysomnography, actigraphy). Further, sleep disorders were not evaluated in this study, and sleep disturbance and sleep aid use were not assessed during internship. Rather, only sleep duration itself was measuring during internship. As such, the potential contributing effects of sleep disorders, such as insomnia and shift work disorder, and internship-related sleep disturbances on anxiety were not examined. Along these lines, shift work is common to medical internship. Our prior work has shown that shift work related shifts in sleep lead to shortened objective sleep and worsened mood [42], but the effects of shift work were not accounted for in the present study.

Short sleep during internship likely represents a combination of endogenously and exogenously reduced sleep duration. Although internship work schedules likely truncated sleep opportunity in the present study, stress exposure itself also disrupts and even shortens sleep, particularly among those with sensitive sleep systems [72-74]. This phenomenon may have driven the effect we observed wherein poor sleepers (with presumably less robust sleep systems, hence the poor sleep) were twice as likely to have short sleep during high stress than good sleepers. While we cannot disentangle the effects of work-related sleep deprivation vs stress-related short sleep on anxiety here, plenty of evidence shows that both endogenous and exogenous short sleep enhances negative emotionality [10] and may thus augment the pathogenicity of sleep disturbance (even if specific underlying mechanisms differ, which is likely the case). Even so, future prospective investigations on stress and sleep would benefit from differentiation between the effects of endogenous vs exogenous short sleep on the risk relationship between sleep disturbance and morbidity.

4.2. Conclusion and recommendations

Prolonged stress appears to amplify vulnerability to anxiety and worry in those with short and disturbed sleep. First-year residents are especially vulnerable to anxiety due to compromised sleep during training; sleep is particularly poor among those consistently working extended shifts, rotating shifts, and on-call nights [41,42]. Interventions targeting sleep onset insomnia and short sleep may improve resilience to anxiety during stress. Early identification of individuals with disrupted or short sleep may provide opportunity to prevent anxiety. Personalized interventions focusing on improving sleep, especially its initiation, may improve resilience to anxiety, particularly among those who are prone to worry. Internet-based delivery of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (iCBTI) [75-78] may be a cost-effective and easily accessible intervention option to potentially reduce risk for clinical anxiety and escalating sleep disruption; and early evidence supports iCBTI for treating anxiety [78] and depressive symptoms [79,80]. Even so, internship work schedules will likely present challenges for CBTI. Those with a complex clinical presentations or comorbid psychiatric illness may be likely best served to consult their primary health provider or a specialist in sleep or mental health services for early and personally tailored intervention.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH101459, PI: Sen). Dr. Kalmbach's effort was supported in part by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (T32HL110952).

Abbreviations list

- CI

confidence interval

- DSM

diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

- GAD

generalized anxiety disorder

- GAD-7

generalized anxiety disorder, 7-item scale

- iCBTI

internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia

- OR

odds ratio

- PHQ-9

patient health questionnaire, 9-item scale

- PSQI

Pittsburgh sleep quality index

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

Dr. Kalmbach has received research support from Merck & Co.

Conflict of interest

The ICMJE Uniform Disclosure Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest associated with this article can be viewed by clicking on the following link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2018.12.001.

References

- [1].Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatr 2005;62(6):593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatr 2005;62(6):617–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hoffman DL, Dukes EM, Wittchen HU. Human and economic burden of generalized anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety 2008;25(1):72–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wittchen HU. Generalized anxiety disorder: prevalence, burden, and cost to society. Depress Anxiety 2002;16(4):162–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord 2011;135(1):10–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Riemann D, Voderholzer U. Primary insomnia: a risk factor to develop depression? J Affect Disord 2003;76(1):255–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Taylor DJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH. Insomnia as a health risk factor. Behav Sleep Med 2003;1(4):227–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Taylor DJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia, depression, and anxiety. Sleep New York Westchester 2005;28(11):1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kalmbach DA, Pillai V, Chen P, et al. Shift work disorder, depression, and anxiety in the transition to rotating shifts: the role of sleep reactivity. Sleep Med 2015;16(12):1532–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Liao D, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration: the most biologically severe phenotype of the disorder. Sleep Med Rev 2013;17(4):241–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fernandez-Mendoza J, Shea S, Vgontzas AN, et al. Insomnia and incident depression: role of objective sleep duration and natural history. J Sleep Res 2015;24(4):390–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kalmbach DA, Pillai V, Arnedt JT, et al. DSM-5 insomnia and short sleep: comorbidity landscape and racial disparities. Sleep 2016;39(12):2101–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kalmbach DA, Arnedt JT, Song PX, et al. Sleep disturbance and short sleep as risk factors for depression and perceived medical errors in first-year residents. Sleep 2017;40(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Harvey AG. Unwanted intrusive thoughts in insomnia. 2005.

- [15].Fernandez-Mendoza J, Calhoun SL, Bixler EO, et al. Sleep misperception and chronic insomnia in the general population: the role of objective sleep duration and psychological profiles. Psychosom Med 2011;73(1):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Buysse DJ. Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep 2014;37(1): 9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Staner L Sleep and anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2003;5(3):249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Meth Psychiatr Res 2012;21(3):169–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yonkers KA, Bruce SE, Dyck IR, et al. Chronicity, relapse, and illnessdcourse of panic disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder: findings in men and women from 8 years of follow-up. Depress Anxiety 2003;17(3):173–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].McEvoy PM, Watson H, Watkins ER, et al. The relationship between worry, rumination, and comorbidity: evidence for repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic construct. J Affect Disord 2013;151(1):313–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Borkovec T, Inz J. The nature of worry in generalized anxiety disorder: a predominance of thought activity. Behav Res Ther 1990;28(2):153–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dickson KS, Ciesla JA, Reilly LC. Rumination, worry, cognitive avoidance, and behavioral avoidance: examination of temporal effects. Behav Ther 2012;43(3):629–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Brosschot JF, Gerin W, Thayer JF. The perseverative cognition hypothesis: a review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. J Psychosom Res 2006;60(2):113–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Watkins ER. Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychol Bull 2008;134(2):163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pillai V, Drake C. Sleep and repetitive thought: the role of rumination and worry in sleep disturbance In: Sleep and affect: assessment, theory, & clinical implications. London: Elsevier; 2014. p. 201–26. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Harvey AG. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther 2002;40(8):869–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Riemann D, Spiegelhalder K, Feige B, et al. The hyperarousal model of insomnia: a review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Med Rev 2010;14(1):19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Palagini L, Moretto U, Dell'Osso L, et al. Sleep-related cognitive processes, arousal, and emotion dysregulation in insomnia disorder: the role of insomnia-specific rumination. Sleep Med 2017;30:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Espie CA, Broomfield NM, MacMahon KM, et al. The attention-intention-effort pathway in the development of psychophysiologic insomnia: a theoretical review. Sleep Med Rev 2006;10(4):215–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Van Dongen H, Maislin G, Mullington JM, et al. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep 2003;26(2):117–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN, Calhoun SL, et al. Insomnia symptoms, objective sleep duration and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in children. Eur J Clin Investig 2014;44(5):493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Harvey AG. Trouble in bed: the role of pre-sleep worry and intrusions in the maintenance of insomnia. J Cognit Psychother 2002;16(2):161–77. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Collier VU, McCue JD, Markus A, et al. Stress in medical residency: status quo after a decade of reform? Ann Intern Med 2002;136(5):384–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Butterfield PS. The stress of residency: a review of the literature. Arch Intern Med 1988;148(6):1428–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pereira-Lima K, Loureiro S. Burnout, anxiety, depression, and social skills in medical residents. Psychol Health Med 2015;20(3):353–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Thomas NK. Resident burnout. JAMA 2004;292(23):2880–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sen S, Kranzler HR, Didwania AK, et al. Effects of the 2011 duty hour reforms on interns and their patients: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(8):657–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Arora VM, Georgitis E, Woodruff JN, et al. Improving sleep hygiene of medical interns: can the sleep, alertness, and fatigue education in residency program help? Arch Intern Med 2007;167(16):1738–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kalmbach DA, Arnedt JT, Song PX, et al. Sleep disturbance and short sleep as risk factors for depression and perceived medical errors in first-year residents. Sleep 2018;40(3):zsw073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Friedman RC, Kornfeld D, Bigger T. Psychological problems associated with sleep deprivation in interns. Acad Med 1973;48(5):436–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Basner M, Dinges DF, Shea JA, et al. Sleep and alertness in medical interns and residents: an observational study on the role of extended shifts. Sleep 2017;40(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kalmbach DA, Fang Y, Arnedt JT, et al. Effects of sleep, physical activity, and shift work on daily mood: a prospective mobile monitoring study of medical interns. J Gen Intern Med 2018:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sen S, Kranzler HR, Krystal JH, et al. A prospective cohort study investigating factors associated with depression during medical internship. Arch Gen Psychiatr 2010;67(6):557–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fiedorowicz JG, Ellingrod VL, Kaplan MJ, et al. The development of depressive symptoms during medical internship stress predicts worsening vascular function. J Psychosom Res 2015;79(3):243–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2008;336(7642):488–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Goebert D, Thompson D, Takeshita J, et al. Depressive symptoms in medical students and residents: a multischool study. Acad Med 2009;84(2):236–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Shanafelt T, Habermann T. Medical residents' emotional well-being. JAMA 2002;288(15):1846–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Guille C, Zhao Z, Krystal J, et al. Web-based cognitive behavioral therapy intervention for the prevention of suicidal ideation in medical interns: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72(12):1192–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The phq-9. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(9): 606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Buysse DJ, Reynolds III CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatr Res 1989;28(2):193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lichstein K, Durrence H, Taylor D, et al. Quantitative criteria for insomnia. Behav Res Ther 2003;41(4):427–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Van Dongen HP, Maislin G, Mullington JM, et al. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep 2003;26(2):117–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Lichstein KL, Rosenthal TL. Insomniacs' perceptions of cognitive versus somatic determinants of sleep disturbance. J Abnorm Psychol 1980;89(1):105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Harvey AG. Pre-sleep cognitive activity: a comparison of sleep-onset insomniacs and good sleepers. Br J Clin Psychol 2000;39(3):275–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Riemann D, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, et al. REM sleep instability-a new pathway for insomnia? Pharmacopsychiatry 2012;45(5):167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Alfano CA, Pina AA, Zerr AA, et al. Pre-sleep arousal and sleep problems of anxiety-disordered youth. Child Psychiatr Hum Dev 2010;41(2):156–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Pigeon W, Perlis M. Insomnia and depression: birds of a feather. Int J Sleep Disord 2007;1(3):82–91. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Pillai V, Roth T, Drake C. The nature of stable insomnia phenotypes. Sleep 2014;39(1):127–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Singareddy R, Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J, et al. Risk factors for incident chronic insomnia: a general population prospective study. Sleep Med 2012;13(4):346–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Guastella AJ, Moulds ML. The impact of rumination on sleep quality following a stressful life event. Pers Indiv Differ 2007;42(6):1151–62. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Pillai V, Steenburg LA, Ciesla JA, et al. A seven day actigraphy-based study of rumination and sleep disturbance among young adults with depressive symptoms. J Psychosom Res 2014;77(1):70–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zoccola PM, Dickerson SS, Lam S. Rumination predicts longer sleep onset latency after an acute psychosocial stressor. Psychosom Med 2009;71(7): 771–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Tsuno N, Besset A, Ritchie K. Sleep and depression. J Clin Psychiatr 2005;66(10):1254–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Dahl RE. The consequences of insufficient sleep for adolescents. Phi Delta Kappan 1999;80(5):354–9. [Google Scholar]

- [66].Kaneita Y, Ohida T, Uchiyama M, et al. The relationship between depression and sleep disturbances: a Japanese nationwide general population survey. J Clin Psychiatr 2006;67(2) :196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Kalmbach DA, Arnedt JT, Swanson LM, et al. Reciprocal dynamics between self-rated sleep and symptoms of depression and anxiety in young adult women: a 14-day diary study. Sleep Med 2017;33:6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Krueger PM, Friedman EM. Sleep duration in the United States: a cross-sectional population-based study. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169(9):1052–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Fernandez-Mendoza J, Li Y, Vgontzas A, et al. Insomnia is associated with cortical hyperarousal as early as adolescence. Sleep 2016;39(5):1029–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep 2013;36(7): 1059–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Kalmbach DA, Pillai V, Arnedt JT, et al. DSM-5 insomnia and short sleep: comorbidity landscape and racial disparities. Sleep 2016;39(12):2101–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Situational insomnia: consistency, predictors, and outcomes. Sleep 2003;26(8):1029–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Drake C, Richardson G, Roehrs T, et al. Vulnerability to stress-related sleep disturbance and hyperarousal. Sleep 2004;27(2):285–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Drake CL, Jefferson C, Roehrs T, et al. Stress-related sleep disturbance and polysomnographic response to caffeine. Sleep Med 2006;7(7):567–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Luik AI, Kyle SD, Espie CA. Digital cognitive behavioral therapy (dCBT) for insomnia: a state-of-the-science review. Curr Sleep Med Rep 2017:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Drake CL. The promise of digital CBT-I. Sleep 2015;39(1):13–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Espie CA, Hames P, McKinstry B. Use of the internet and mobile media for delivery of cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy. Sleep Med Clin 2013;8(3): 407–19. [Google Scholar]

- [78].Pillai V, Anderson JR, Cheng P, et al. The anxiolytic effects of cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia: preliminary results from a web-delivered protocol. J Sleep Med Disord 2015;2(2):a–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Christensen H, Batterham PJ, Gosling JA, et al. Effectiveness of an online insomnia program (SHUTi) for prevention of depressive episodes (the Good-Night Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3(4): 333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Cheng P, Luik AI, Fellman-Couture C, et al. Efficacy of digital CBT for insomnia to reduce depression across demographic groups: a randomized trial. Psychol Med 2018:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]