Abstract

DNA extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections is often inadequate for sequencing, due to poor yield or degradation. We optimized the proteinase K digest by testing increased volume of enzyme and increased digest length from the manufacturer’s protocol using 54 biospecimens, performing the digest in centrifuge tubes. Doubling the quantity of proteinase K resulted in a median increase in yield of 96%. Applying the optimized proteinase K protocol to sections deparaffinized on microscope slides generated a further increase in yield of 41%, but only at >50,000 epithelial tumor cells/section. DNA yield now correlated with (χ2 = 0.84) and could be predicted from the epithelial tumor cell number. DNA integrity was assayed using end point multiplex PCR (amplicons of 100–400 bp visualized on a gel), quantitative PCR (qPCR; Illumina FFPE QC Assay), and nanoelectrophoresis (DNA Integrity Numbers [DINs]). Generally, increases in yield were accompanied by increases in integrity, but sometimes qPCR and DIN results were conflicting. Amplicons of 400 bp were almost universally obtained. The process of optimization enabled us to reduce the percentage of samples that failed published quality control thresholds for determining amenability to whole genome sequencing from 33% to 7%.

Keywords: DNA Integrity Number, genomic screen tape, Illumina FFPE QC Assay, quality control

Introduction

The development and application of DNA sequencing in research and clinical medicine has driven an increase in the number of tissue biospecimens upon which DNA extractions are performed. Given that routine clinical workflows deliver the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks that are a requisite for pathologists, it is commonplace to additionally use the same FFPE biospecimens for DNA sequencing. There have been several studies demonstrating that DNA extracted from FFPE biospecimens is inherently amenable to sequencing, with the resultant sequencing data being either equivalent to or inconsequentially different from those generated from “gold standard” frozen biospecimens.1–5

However, there remains a problem. Typically, a proportion of FFPE biospecimens in a given study (the magnitude of which depends on factors such as the sequencing platform adopted) yield insufficient DNA for sequencing or DNA that is too fragmented for library preparation. For example, in the pilot study for the 100,000 Genomes Project in the United Kingdom, 31% of the FFPE blocks were excluded for whole genome sequencing because the DNA they yielded was inadequate in quantity or too degraded.6

This problem can be tackled at the sequencing stage by using library preparation methods (e.g., the AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel from Illumina; San Diego, CA) and sequencers (e.g., the Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine from Thermo Fisher; Waltham, MA) that are more amenable to the relatively low quantities of fragmented DNA that typify FFPE biospecimens.7 In addition, laboratories performing DNA extractions can optimize their protocols to maximize (or at least improve) the quantity and quality of DNA they purify. If such protocol optimization was performed on a large enough scale, fewer patients would be refused personalized medicine or be subjected to additional invasive procedures to acquire additional tissue. Furthermore, a greater proportion of biobanked biospecimens would be deemed amenable to research. For prospective studies, a reduction in the demand to have a fresh frozen biospecimen for sequencing in addition to the FFPE biospecimen required for pathology would mean the logistical difficulties involved in the collection and storage of frozen biospecimens would be less onerous.

A prerequisite for a laboratory undertaking such an optimization process is an understanding of which steps in the DNA extraction process are critical in determining DNA yield and integrity. Ideally, they should also be steps that are relatively easy to optimize. After sections have been cut from the tissue block, the paraffin wax that encapsulates and infiltrates the tissue is removed. This deparaffinization step is usually followed by a proteinase K digest, in which potentially contaminating proteins, including any DNase that might be present, are eliminated. After the proteinase K digest, formaldehyde crosslinks can be reversed in a heating step, after which the DNA is purified, typically with a commercial kit that uses silica spin column or magnetic bead technology.

We present a study in which we first evaluate three different proteinase K digests in respect of DNA extracted from 54 clinical FFPE tissue blocks, after deparaffinization had been performed in centrifuge tubes. We then see whether the most effective proteinase K protocol can be further improved by switching the deparaffinization method to one performed on glass microscope slides.

Methods

Biospecimens

A total of 54 FFPE tumor biospecimens of standardized dimensions (5 mm3) were used for this study (17 breast, 5 kidney, 1 bladder, 1 prostate, 2 carcinosarcoma, 15 ovary, 3 uterus, 6 endometrium, 1 fallopian tube, 1 omentum, 1 colon, and 1 adenoid carcinoma). The tissues were collected during routine surgery at three London hospitals then fixed for the same period of time (24 hr) in 10% neutral buffered formalin. The fixed tissue was processed into FFPE blocks on a Tissue-Tek Vacuum Infiltration Processor 5 (Sakura Finetek; Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands) using a conventional protocol. The decision to maintain a standardized fixation time for all the biospecimens in the study meant that the cold ischemic times of the biospecimens varied. The tissue blocks had been stored in dark at room temperature, without humidity control, for 34 to 313 days (median, 133 days) before they were used for this project.

The biospecimens were issued by the Imperial College Healthcare Tissue Bank, which is approved by the National Research Ethics Service (UK) to release human material for research (12/WA/0196). Written informed consent had been obtained from each patient, and ethical approval for this study was granted by the Imperial College London National Health Service Trust Ethics Committee.

Experimental Design

The DNA extractions were performed in two parts. First, three different proteinase K digest protocols were evaluated to establish whether increasing the volume of proteinase K or increasing the length of proteinase K digest from that specified in the DNA extraction kit’s protocol would increase DNA yield. The three different proteinase K protocols were all performed after the tissue sections had been deparaffinized as per the extraction kit’s protocol (in centrifuge tubes using 1 ml deparaffinization reagents). Then, the proteinase K protocol that returned the highest DNA yield was applied to sections cut from the same FFPE tissue blocks, but which had been deparaffinized on glass microscope slides immersed in much higher volumes of deparaffinization reagents. DNA concentrations were then reassayed and DNA integrity analyses performed.

Tissue Sectioning and Cellularity Assessment

Each DNA extraction was performed using 10 sections of 4 µm, which were placed as scrolls in 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes (10 sections per tube) for the three proteinase K digest protocols or melted onto uncharged Surgipath microscope slides (Leica Biosystems; Milton Keynes, UK) at one section per slide for the fourth method. The sections were distributed such that each of the three tubes (i.e., proteinase K digestion protocols) had a similar representation of sections cut at different depths within the block. However, as the deparaffinization on slides was performed later, these sections were cut from deeper within the block. Although all sections used in the study contained the same volume of tissue (5 mm2 × 4 µm thick), a cellularity assessment was performed using an additional 4-µm section that was stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The stained slide was scanned using an AxioScan Z1 digital microscope (Carl Zeiss; Cambridge, UK) and the resultant digital image opened using GNU Image Manipulation Software (http://www.gimp.org). A grid of identical size was superimposed on each digital image (one image per tissue block, n=43) and the number of tumor epithelial cells was manually counted in ≥10 randomly selected grid squares per slide. The total number of tumor cells per section was estimated by multiplying the mean number of tumor cells per grid square by the number of grid squares that contained tissue, after a deduction had been made in respect of the non-cellular portion of any grid squares that only partially contained tissue.

DNA Extraction and Quantification

For the first set of DNA extractions, the sections in centrifuge tubes were deparaffinized as per the DNA extraction kit’s instructions. The sections were vortexed in 1 ml Histoclear xylene substitute (National Diagnostics; Lichfield, UK) for 10 sec and then centrifuged for 2 min to pellet the tissue. The Histoclear was pipetted off and the vortex/centrifuge step repeated using 100% ethanol. The ethanol was pipetted off and the tube left for 10 min to allow any residual ethanol to evaporate. DNA was then extracted using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen; Hilden, Germany) manually as per the kit’s protocol, but with one tube per FFPE tissue block undergoing each of the following proteinase K digests:

Protocol 1: 20 µl proteinase K for 24 hr (manufacturer’s protocol);

Protocol 2: 20 µl proteinase K for 5 hr, topped up with a further 20 µl proteinase K and digested for a further 19 hr (24 hr total);

Protocol 3: 20 µl proteinase K for 72 hr.

In all instances, proteinase K supplied in the DNA extraction kit was used (20 mg/ml, 45 mAU/mg protein) and the digest performed on a heating block at 56C. The manufacturer’s protocol specifies a proteinase K volume of 20 µl and an incubation of “1 hr or until the sample has been completely lysed.” Our historical experience using this extraction kit is that an 18- to 24-hr digest is necessary for lysis to be visually complete in all 12 samples of a typical DNA extraction run. Therefore, protocol 1 represents that of the manufacturer.

DNA extractions were carried out manually in five batches per protocol, with each batch containing 11 samples plus an in-process control that consisted of sections cut from an FFPE cell pellet of the HUCC cholangiocarcinoma cell line, prepared as previously described.8 The optional RNase digest was included to prevent copurification of RNA.9 DNA was eluted in 50 µl of the Tris-EDTA buffer supplied in the kit (two elutions of 25 µl).

DNA concentrations were assayed by PicoGreen spectrofluorometry using the QuBit dsDNA broad range assay kit on a QuBit 2.0 spectrofluorometer (both from Life Technologies; Paisley, UK) and by OD260 nm spectrophotometry using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific; Perth, UK). DNA purities were assessed using OD 260/280 and 260/230.

For the comparison between deparaffinization methods, only protocol 2 (40 µl/24 hr) was used for the proteinase K digest because it had returned the highest yield in both quantification methods when deparaffinization had been performed in tubes. The slides containing the sections were placed in glass racks (20 slides/rack) and then immersed in sequential baths containing approximately 200 ml of Histoclear (twice for 10 min) and then ethanol (100%, 95%, then 70%) for 1 min each. After residual ethanol had evaporated from the slides, the tissue was scraped from the slides into 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes using a scalpel and a drop of nuclease-free HyClone molecular biology grade water (GE Healthcare; Little Chalfont, UK). All 10 sections from the same FFPE block were scraped into the same tube, and the scalpel blade was changed between each block’s slides. DNA was then extracted using the protocol previously used for the tubes, applying the protocol 2 (40 µl/24 hr) proteinase K digest. There were six rounds of extractions, each round consisting of seven (n=1) or nine (n=5) tissue blocks, plus the same in-process cell pellet control as used in the previous tube deparaffinization protocols.

DNA was quantified using the QuBit dsDNA broad range assay kit on the QuBit 2.0 spectrofluorometer as previously used in the tube deparaffinization extractions. To avoid batch effect bias with regard to the quantification, all DNA extracts were then quantified a second time in 96-well plates by Pico Green spectrofluorometry, using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA assay kit (Life Technologies) and a Synergy Mx spectrofluorometer (BioTek Instruments; Colmar, France).

DNA Integrity Assessment

DNA integrity was assessed using nanoelectrophoresis (DNA Integrity Numbers [DINs]), quantitative PCR (qPCR; Illumina FFPE QC Assay), and multiplex PCR (different amplicon lengths of the GAPDH gene). In addition, the percentage of the total DNA that was double stranded (dsDNA) was calculated for each sample using the spectrophotometry (total DNA) and spectrofluorometry (specific for dsDNA) concentrations using the following equation: % dsDNA = spectrofluorometry concentration/spectrophotometry concentration × 100.

DINs range from 1 (DNA completely degraded) to 10 (DNA completely intact) and were measured by running 1 µl of each sample on Genomic DNA ScreenTapes and reagents in a 4200 TapeStation (all Agilent Technologies; Diegem, Belgium) as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

The Illumina FFPE QC Assay (Illumina) is designed to determine a DNA sample’s amenability to sequencing by comparing its cycle threshold number (Cq) with that from a Reference DNA Template supplied in the kit to generate a ΔCq value (∆Cq = Sample Cq − Reference Template Cq). Lower ∆Cq values denote higher DNA integrity, and negative numbers occur when the DNA of the tested sample has greater integrity (and therefore a lower Cq) than that of the Reference Template. Each sample was assayed in triplicate, using 2 ng DNA (assessed using the Quant-iT dsDNA assay), 1 µl primers supplied in the assay, and 5 µl Platinum SYBR Green qPCR 2× SuperMix and 50 nM ROX (both from Invitrogen; Paisley, UK) in a final volume of 10 µl. Reactions were carried out in Fast 96-well plates in an ABI 7500 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems; Nieuwerkerk aan Den IJssel, Netherlands), with each plate containing the requisite positive and negative controls plus the Reference DNA. The raw data were analyzed using SDS software v. 1.4.2 (Applied Biosystems).

The multiplex PCR assay is an assay in which 100, 200, 300 and 400 bp amplicons of the GAPDH gene are simultaneously amplified by end point PCR and the extent of DNA fragmentation assessed by seeing how many of the amplicons can be visualized on a gel. The primers and cycling temperatures were those specified by van Beers et al.10 We modified the protocol in that 35 cycles of PCR were performed, with each reaction consisting of 100 ng DNA (assessed using spectrophotometry) and 20 pM each primer in a final volume of 20 µl, with 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, and 0.05 U/µl AmpliTaq Gold DNA Polymerase (Applied Biosystems). The reactions were carried out in 0.2 µl PCR tubes on a C1000 Thermal Cycler (BioRad; Schiltigheim, France) and the amplicons visualized by running the post-amplified product on a 1.5% agarose gel that was stained with GelRed (Biotium; Fremont, CA) and imaged using an ImageQuant (GE Healthcare; Paris, France). We performed the assay on all samples from which sufficient DNA was available (3 blocks in respect of all four protocols, 3 blocks in respect of three protocols, 10 blocks in respect of two protocols, and 15 blocks in respect of one protocol: a total of 54 reactions).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot software v. 12.5 (Systat Software; San Jose, CA). One-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare the three proteinase K digest protocols where sections were deparaffinized in tubes. When statistical significance was found, the Student–Newman–Keuls method was applied to identify which of the pairwise comparisons the statistical significance applied to. Paired t-tests were used to compare the results where deparaffinization on microscope slides was compared with tubes, but in which the 40 µl/24 hr proteinase K digest protocol was universally applied. In all instances, ranks were used when data were not normally distributed. Correlations were tested using Pearson’s product-moment or Spearman’s rank-order correlation depending on whether the data were normally distributed or not.

Results

Comparison of QuBit and Quant-iT Pico Green Assays

The two Pico Green assays (dsDNA Broad Range assay performed in 0.5 ml tubes, quantified in the QuBit spectrofluorometer, and Quant-iT dsDNA assay kit performed in 96-well plates, quantified in the Synergy Mx spectrofluorometer) correlated almost perfectly (χ2 = 0.99, p<0.001). In all instances, when a DNA sample could not be quantified using one of the assays, it was also unquantifiable in the other assay. Although data analyses using either of the Pico Green data sets returned almost identical results, the statistical analyses in this study are performed using data from the Quant-iT dsDNA assay, because in this assay quantification was performed for all four groups together, thereby avoiding any bias due to batch effect.

DNA Yield and Different Proteinase K Protocols (Deparaffinization in Tubes)

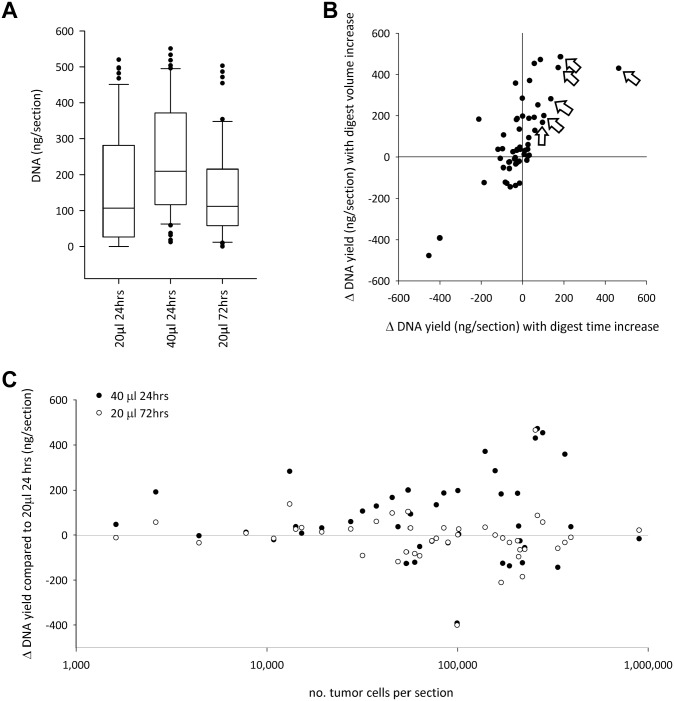

All 54 FFPE blocks returned quantifiable DNA when the 40 µl/24 hr proteinase K digest was performed. However, when the proteinase K volume was 20 µl, 12% of samples (n=6) failed to yield DNA in the 24-hr digest and 6% (n=3) in the 72-hr digest. With deparaffinization performed in tubes, the most effective of the three protocols in terms of DNA yield was the 40 µl/24 hr digest (median, 210 ng DNA/section). Halving the proteinase K quantity to 20 µl reduced median yield by an almost equivalent proportion: to 107 ng/section for the 24-hr digest and 112 ng/section for the 72-hr digest (Fig. 1A). The difference in yields in all pairwise comparisons was statistically significant (p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Influence of proteinase K digest on DNA yield. The boxes are the 25th to 75th percentiles, intersected by the median. The whiskers show the 10th and 90th percentiles, and each spot represents one remaining data point. (A) The 40 µl/24 hr digest returned the highest yield. The difference between the three protocols is statistically significant in all pairwise comparisons (p<0.05). (B) Changes in DNA yield, relative to the 20 µl/24 hr proteinase K protocol, generated by increasing the proteinase K digest volume to 40 µl compared with changes induced by increasing the digest length to 72 hr. Tissue blocks tended to have a shared degree of resilience to either change in protocol. Each data point is a tissue block. The white arrows identify the six blocks with the greatest increase in yield when the digest time was lengthened, as discussed in the text. (C) There was a moderate positive correlation between DNA yield and cellularity in the 20 µl/24 hr digest (see text), the magnitude of which increased in proportion to epithelial tumor cellularity when the volume of proteinase K was increased to 40 µl (black circles). However, the magnitude of the change in DNA yield was unrelated to cellularity when the digest length was increased to 72 hr (white circles). Black and white circles that are aligned vertically are the two digests from the same tissue block. Note the logarithmic scale in the x-axis.

For the cell pellet control, mean yields (nanograms/section) for the five extractions were 12.9 (20 µl/24 hr), 16.8 (40 µl/24 hr), and 11.8 (20 µl/72 hr). As with the samples, the higher yield in the 40 µl/24 hr digest compared with the other two protocols was statistically significant (p=0.01), but unlike what was seen in the samples, the difference between the 20 µl/24 hr protocol and the 20 µl/72 hr protocol was not statistically significant (p=0.47).

The slight median increase in yield when 20 µl proteinase K was used but the digest time was increased from 24 to 72 hr was in respect of the data set as a whole, not as a consequence of each biospecimen yielding slightly more DNA (Fig. 1B). Less than half (22 of the 54 blocks, 41%) actually returned an increase in yield when the digest time was increased (the data points on the right of the vertical zero axis in Fig. 1B). The increase in yield predominantly occurred in the blocks that were lowest yielding in the 24-hr digest: 84% of the blocks that were the lowest yielding quartile in the 24-hr digest returned an increase in yield when the digest time was increased. For example, the six blocks that showed the greatest increase in yield when the digest time was lengthened (identified by white arrows in Fig. 1B) had a mean DNA concentration of 22 (range, 0–70.5) ng/section in the 24-hr digest. (The mean of all 54 blocks was 167 ng/section for this digest.) For the aforementioned six blocks, increasing the digest length to 72 hr increased mean DNA yield from 22 to 216 ng/section.

The pattern seen when increasing the proteinase K digest time contrasts with that seen when increasing the proteinase K volume from 20 to 40 µl (digest time was retained at 24 hr). Now, 35 (65%) of the 54 blocks recorded an increase in yield. These included all of the blocks that were in the lowest yielding quartile of the 20-µl digest.

There were 21 blocks (39% of the total) where the block responded to the increase in both digest time and digest length from the 20 µl/24 hr digest with an increase in yield (the upper right quadrant in Fig. 1B). In these blocks, the magnitude of the increase was much greater with the volume increase compared with the time increase (an increase of 192 ng/section compared with 57 ng/section, p=0.009). There were 14 blocks (26% of the total) where yield increased when the digest volume was increased but yield decreased when the digest length was increased from the 20 µl/24 hr digest (data points in the upper left quadrant of Fig. 1B). However, there was only one block which responded in the opposite way (the data point in the lower right quadrant of Fig. 1B).

There was a tendency for each tissue block to have a particular resilience/vulnerability to changes in digest protocol. A tissue block that responded to the increase in proteinase K volume with a relatively large change in its yield would probably also respond to an increase in the digest length with a relatively large change in yield (although not necessarily in the same direction), and similarly, a block that showed relative resilience to the change in proteinase K volume in respect of its yield would be more likely to also show resilience to the change in digest length (Fig. 1B). There was a positive correlation (χ2 = 0.68) between the magnitude of the change in DNA yield generated by increasing the digest volume and increasing the digest length from the 20 µl/24 hr digest.

Influence of Cellularity on DNA Yield in Different Proteinase K Digests

There was a moderate positive correlation between DNA yield and the number of epithelial tumor cells per section, with a slightly higher correlation found in the 40 µl/24 hr digest (χ2 = 0.57, p<0.001) compared with the two digests using 20 µl proteinase K (χ2 = 0.43, p=0.004 for the 24-hr digest and χ2 = 0.42, p=0.005 for the 72-hr digest). When the length of the digest was increased from 24 to 72 hr (retaining the proteinase K volume at 20 µl), the magnitude of the change in DNA yield was completely unrelated to the cellularity of the sample (Fig. 1C). In contrast, when the volume of proteinase K was increased from 20 to 40 µl (retaining the 24-hr digest length), the largest increases in DNA yield were in the most cellular samples (also Fig. 1C). Therefore, for samples >10,000 epithelial cells/section, increasing proteinase K volume was a much more effective protocol change to improve DNA yield than increasing the digest length.

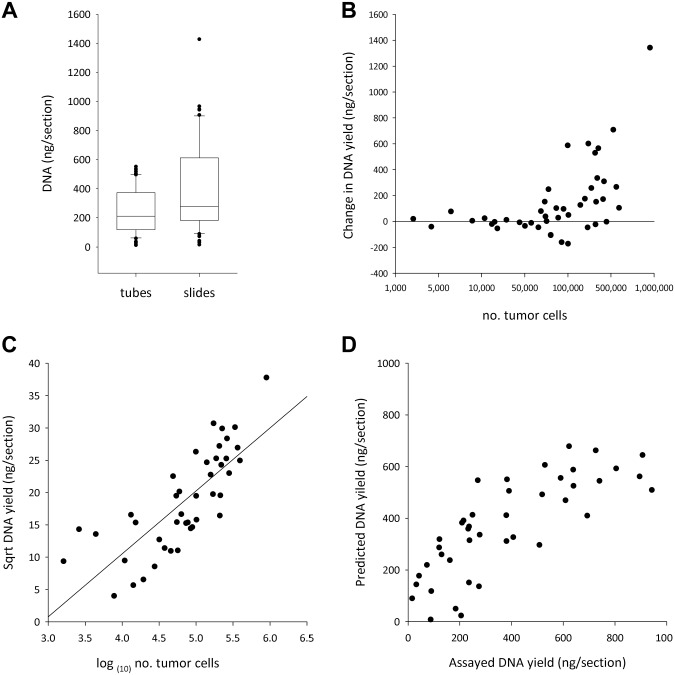

Influence of Deparaffinization Method on DNA Yield

It was clear that the most effective protocol in terms of maximizing DNA yield was the 40 µl/24 hr proteinase K digest. When this was applied to sections deparaffinized on glass microscope slides, a further improvement in median DNA yield was seen, from the previously described 210 ng/section to 297 ng/section with deparaffinization in tubes (p<0.001) (Fig. 2A). The magnitude of the increase in DNA yield depended on the number of tumor epithelial cells per section: at <50,000 epithelial tumor cells/section, there was no difference in yield (mean yields were 156 ng/section for tubes and 154 ng/section for slides [n=14, p=0.90]), but at >50,000 epithelial tumor cells/section, the magnitude of the increase in yield obtained by switching to slide deparaffinization progressively increased with increasing cellularity (Fig. 2B). We previously saw that when deparaffinization was performed in tubes, increasing the proteinase K volume from 20 to 40 µl enabled progressively more DNA to be extracted from more cellular sections; now we find this pattern being amplified further with deparaffinization on slides.

Figure 2.

Effect of changing the deparaffinization protocol on DNA yield. (A) Changing the deparaffinization protocol from tubes to slides generated an increase in DNA yield (p<0.001). The parameters of the box plot are as in Fig. 1A. (B) The magnitude of the increase in DNA yield gained when switching to slide deparaffinization was dependent on the cellularity of the sample, but only at >50,000 epithelial tumor cells per section. Note the logarithmic scale in the x-axis. (C) When deparaffinization was performed on slides, DNA yield correlated to the number of tumor cells using the equation √DNA yield (ng DNA/section) = −28.45 + (9.742 × log(10) no. of tumor cells). The linear regression line is shown. (D) Comparison of the DNA yield predicted using the epithelial tumor cell count and the yield assayed by Pico Green spectrofluorometry.

With slide deparaffinization, the positive correlation between the number of epithelial tumor cells and DNA yield was also higher (χ2 was 0.57 for scrolls but 0.84 for slides, p<0.001). Performing square root transformation normalized the DNA yield data, and linear regression returned the following equation: √DNA yield (ng DNA/section) = −28.45 + (9.742 × log(10) no. of tumor cells) (R2= 0.60, p<0.001) (Fig. 2C). Using this equation, it was possible to predict the DNA yield per section from the number of epithelial tumor cells per section with a moderate degree of accuracy (Fig. 2D).

DNA Purity and % dsDNA

All four protocols returned pure DNA, with median 260:230 of 2.01 to 2.32 and median 260:280 of 1.84 to 1.89. The 40 µl/24 hr digest had the highest median % dsDNA at 51.9% (deparaffinization in tubes) and 52.3% (deparaffinization on slides). The 20 µl/24 hr digest had median 36.8% dsDNA and the 20 µl/72 hr digest had median 44.0% dsDNA. However, the differences were not statistically significant.

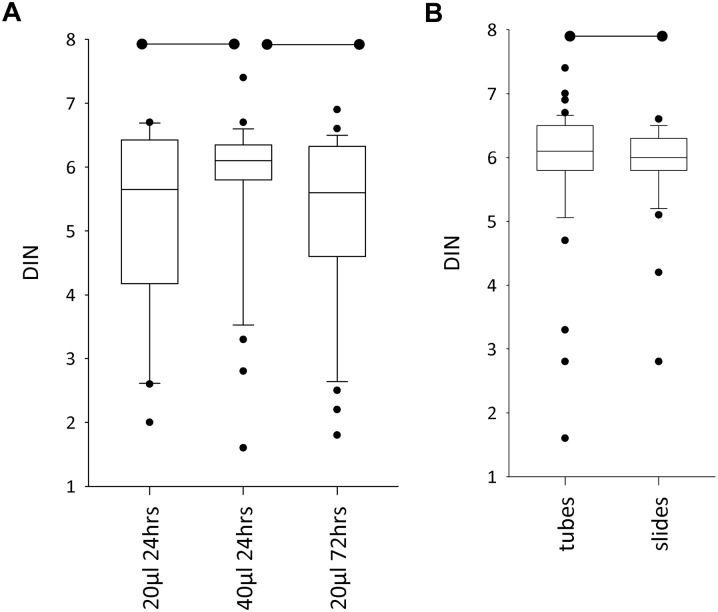

DNA Integrity With DIN

In the comparison of three proteinase K digests (deparaffinization carried out in tubes), DINs were successfully generated in all three digest protocols for 30 of the FFPE blocks, so these data were used for comparative analyses. There were no differences in the numbers of samples that failed to generate DINs across the three digests. Median DINs were highest in the 40 µl/24 hr digest: 6.1 compared with 5.7 (20 µl/24 hr) and 5.6 (20 µl/72 hr). The 40 µl/24 hr digest also had a notably higher 25th percentile (5.8) compared with the two digests using 20 µl proteinase K (4.2 and 4.6) (Fig. 3A). The higher DINs in the 40 µl/24 hr digest were statistically significant compared with the two 20 µl digests (p<0.05), but the difference between the two 20 µl digests was not statistically significant (p≥0.51).

Figure 3.

Effect of different Proteinase K digest protocols and deparaffinization methods on DNA Integrity Number (DIN). (A) When deparaffinization was performed in tubes, the 40 µl/24 hr proteinase K digest had the highest median DIN and a considerably higher 25th percentile DIN than either of the digests using 20 µl proteinase K. When 20 µl proteinase K was used, extending the digest time from 24 to 72 hr had no statistically significant effect. (B) Median DINs and the 75th percentile were both slightly higher when sections were deparaffinized in tubes compared with on microscope slides. Although the difference was statistically significant, it was very small in magnitude. The parameters of the box plot are as in Fig. 1A, and the horizontal lines with start and end dots denote the groups that are statistically significantly different from each other (p<0.05).

For the comparison between deparaffinization in tubes and on slides (in which all samples had the same 40 µl/24 hr proteinase K digest), there were 43 tissue blocks which successfully generated DINs in both protocols. Median DINs in this data set were 6.1 for tube deparaffinization and 6.0 for slide deparaffinization (p=0.02). Provided a DIN was returned, there were no differences in DIN between the more/less cellular tissue blocks, although the extractions that failed to return a DIN did so because of their low yield, and these tended to be from FFPE blocks of low cellularity.

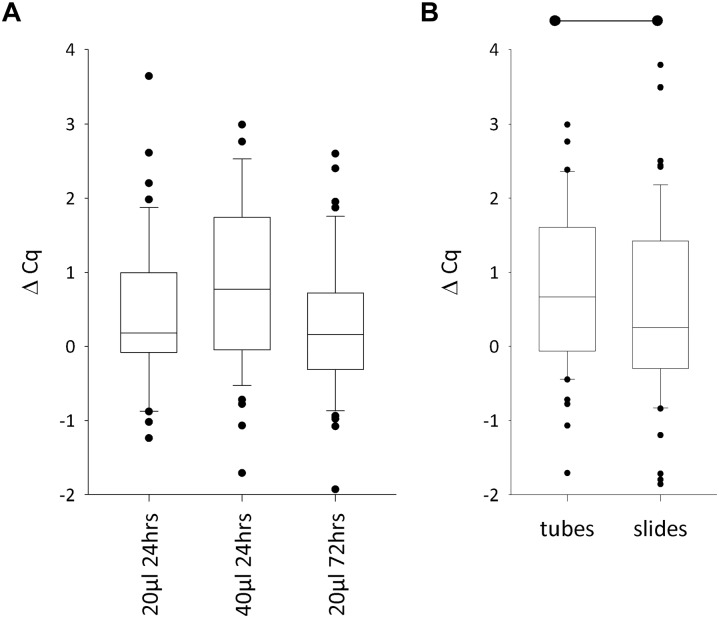

DNA Integrity With Illumina FFPE QC Assay

The Illumina FFPE QC assay was applied to all the samples that returned quantifiable DNA, and a ∆Cq was obtained successfully in every sample assayed. When deparaffinization had been performed in tubes, unlike with DIN, the difference in ∆Cq values was not statistically significant in any pairwise comparison (p=0.13) (Fig. 4A). In terms of the percentage of DNA extractions that had a ∆Cq <2.0 (i.e., those defined by Serizawa et al. as being more amenable to whole genome sequencing), when deparaffinization was performed in tubes, 18% of the 40 µl/24 hr digest, 7% of the 20 µl/24 hr digest, and 4% of the 20 µl/72 hr digest fell above the specified threshold and therefore failed the applied acceptance critera.11 Although these failure rates indicate that the 40 µl/24 hr digest was the poorest performer, it should be noted that only in the 40 µl/24 hr digest was DNA extracted from all the FFPE blocks and a ∆Cq obtained from all the samples. If extractions that failed to yield DNA are taken into account as assay failures, then the failure rate is 18% for both the 40 µl/24 hr and 20 µl/24 hr digests and 10% for the 20 µl/72 hr digest.

Figure 4.

Effect of different proteinase K digest protocols and deparaffinization methods on DNA integrity assayed using the Illumina FFPE QC Assay. (A) The differences between the three proteinase K protocols were not statistically significant. (B) When the 40 µl/24 hr proteinase K digest was performed, switching to deparaffinization on slides lowered the ∆Cq values. Lower ∆Cq values denote improved DNA integrity. The parameters of the box plot are as in Fig. 1A, and the horizontal lines with start and end dots denote the groups that are statistically significantly different from each other (p=0.01).

Switching from tube deparaffinization to slide deparaffinization generated a statistically significant reduction in ∆Cq (equating to an improvement in DNA integrity), from median ∆Cq = 0.67 for tubes to 0.26 for slides (n=54, p=0.01) (Fig. 4B). In addition, the percentage of blocks failing to meet the threshold reduced from 17% to 9%. There were a total of 18 patients whose FFPE blocks failed the assay in at least one of the four protocols; 15 of these failed only in respect of one protocol and 1 failed in two protocols, 1 failed in three protocols, and 1 failed in all four protocols.

When deparaffinization was performed on slides (but not in any of the tube-deparaffinized protocols), there was a moderate positive correlation between tumor epithelial cell number and ∆Cq (χ2 = 0.42, p=0.006). The mean ∆Cq in the most cellular 20% of blocks was higher than in the least cellular 20% of tissue blocks (mean ∆Cq = 1.36 and −0.21, respectively; p<0.001). There was also a moderate positive correlation in the slide-deparaffinized samples between ∆Cq and % dsDNA (χ2 = 0.43, p=0.001). Therefore, in the slide-deparaffinized sections, the more cellular samples had higher (i.e., poorer) ∆Cq values as well as higher % dsDNA values. For the entire data set (n=207), the positive correlation between % dsDNA and ∆Cq remained, but it was weak (χ2 = 0.20, p=0.004).

Given that both DIN and Illumina FFPE QC assay quantify DNA integrity, but with higher values denoting higher integrity in DIN and vice versa for the Illumina assay, a negative correlation between them would be logical. However, no such correlation was found between ∆Cq and DIN in any of the four protocols (χ2 varied between 0.0 and 0.22, p>0.16) or in the combined data set (χ2 = 0.09, p=0.24). Therefore, there was no consensus between the two assays as to which samples were high or low in integrity.

DNA Integrity With Multiplex PCR

The multiplex PCR assay amplifies 100, 200, 300, and 400 bp of the GAPDH gene and assesses the results using an agarose gel. For tube-deparaffinized extractions, the assay was performed on DNA extracted from 17 FFPE blocks for the 40 µl/24 hr digest, 13 blocks for the 20 µl/24 hr digest, and 12 blocks for the 20 µl/72 hr digest. In addition, 12 blocks where the 40 µl/24 hr digest was performed after deparaffinization on slides were tested.

All four amplicons were obtained from all the extractions, with the exception of those from one FFPE block, in which all four protocols were applied to the assay. This block only generated the 100- and 200-bp amplicons, but did so in all four extractions. Given that this fragmented DNA (<300 bp in length) was present in the extractions from all three proteinase K digests, it relates to the quality of the FFPE biospecimen, not the proteinase K digest protocol or deparaffinization method. This biospecimen was the only one in which the DNA failed the Illumina FFPE QC assay in all four extraction protocols (mean ∆Cq = 2.76); it also returned poorer than average DIN (mean = 3.2 for the four protocols).

Influence of Other Preanalytical Variables on DNA Yield and Integrity

There was no evidence that biospecimens of a particular tissue type or collection site responded in a different way to any of the changes in protocol, in respect of either DNA yield or integrity. There was no correlation between storage time and DNA yield or storage time and DNA integrity in any of the extraction protocols.

Discussion

Our study found that the proteinase K digest protocol is a critical factor in DNA extraction. When deparaffinization is performed in tubes, the 40 µl/24 hr protocol (more precisely, performing the first part of the digest using 20 µl, then adding an additional 20 µl of proteinase K 5 hr into the digestion) was unequivocally best in respect of returning the highest DNA yield. It is less obvious whether the increase in yield is accompanied by an increase in integrity, because although DINs were highest in the 40 µl/24 hr digest, DNA from the 20µl/72 hr digest returned better results in the Illumina FFPE QC Assay (a lower ∆Cq).

Given that the purity of DNA in all digests was equally high, we do not think that PCR-inhibiting contaminants eluted with the DNA into the elution buffer are a factor. It is possible that the additional heat applied (at 56C) in the longer digest reverses more of the formaldehyde adducts that compromise PCR efficiency. It is also possible that the larger DNA molecules recovered from the 40 µl/24 hr digest (and which increase DIN) are actually a myriad of small fragments that are crosslinked with each other to form a conglomerate, but in which each DNA strand is less amenable to PCR.

Alternatively, there might be more template in the 20 µl/72 hr qPCR reactions. Although each reaction in the Illumina FFPE QC Assay is normalized in respect of starting quantity, this normalization is performed using Pico Green quantification (i.e., dsDNA only). Given that the 20 µl/72 hr digest had lower % dsDNA values than the 40 µl/24 hr digest (albeit falling short of statistical significance), the DNA in the longer digest tended to be enriched in unquantified single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). If some ssDNA was amplifiable in qPCR, the result would be a lowering of the ∆Ct, giving the false impression of DNA of higher integrity.

We are therefore unable to state with confidence which proteinase K protocol offered the highest DNA integrity. DNA from the 40 µl/24 hr digest was highest in terms of yield, DIN, and % dsDNA (but not statistically significantly so in the latter). All of the digests were equally good in the multiplex PCR assay, and the 20 µl/72 hr digest was best in terms of ∆Cq (but not statistically significantly so). However, the magnitude of the increase in yield gained by selecting the 40 µl/24 hr digest is much larger than the magnitude of the differences between the integrity assays, and therefore selecting the 40 µl/24 hr digest will maximize a user’s chance of having sufficient DNA to perform downstream analyses.

Switching from deparaffinization in tubes to deparaffinization on slides (but keeping the 40 µl/24 hr proteinase K digest) generated a further increase in yield, an improved (i.e., lower) ∆Cq, but it also negatively impacted (i.e., lowered) DIN. The % dsDNA values were very similar indeed for each deparaffinization method, so an enrichment of ssDNA cannot explain the lower ∆Cq in the slide-deparaffinized samples compared with the tube-deparaffinized samples. We think the most likely explanation is that while the additional DNA purified with slide deparaffinization is very slightly smaller in size (the difference was only 0.1 DIN units), it is more functionally amenable to PCR.

We think this improved functionality to PCR is most likely a consequence of the greater volume of deparaffinization reagents used in slide deparaffinization compared with tube deparaffinization (200 ml per rack of slides rather than 1 ml per tube). It is also possible that the sequential rinses in ethanol of decreasing percentage (100%, 95%, then 70%) followed by the drop of water that was added to the slide after deparaffinization (to aid the scraping of the tissue into the tube) rehydrated the tissue after ethanol wash, making the tissue more amenable to proteinase K digestion. These factors might also have enhanced the lysability of tissue deparaffinized on slides compared with that deparaffinized in tubes, where only 100% ethanol was used and no water was added (as per the kit manufacturer’s protocol).

Many of the steps involved in extracting DNA from FFPE tissue biospecimens are known to be influential in determining the yield and integrity of the DNA ultimately purified (e.g., the deparaffinization method, the proteinase K digest protocol, the DNA purification technology [precipitation, magnetic beads, or silica columns], the choice of extraction kit within the selected technology, the DNA elution volume (higher elution volumes return greater yields of more diluted DNA), and whether the process is automated or performed manually).12 In addition, factors relating to the biospecimen itself (e.g., ischemic time, fixation time, tissue processing protocol, and archival time) add another layer of complexity and can also be influential.13–16

Consequently, a laboratory’s DNA extraction protocol will not be maximally effective for all biospecimens, given their inherent diversity, and users must accept a compromise protocol that returns DNA that exceeds realistic, minimum quality control (QC) thresholds in respect of yield and integrity in the highest percentage of samples. The QC thresholds applied must depend on the downstream technology, noting that within one technology type there will likely be multiple platforms, some of which are more amenable to the inherent variability in quality that characterizes DNA extracted from FFPE tissue.

It is logical for users to assume that the manufacturer of the DNA extraction kit will have optimized their protocol, particularly where a commonly used kit from a manufacturer well known to invest significantly in research and development is chosen, and even more so when all reagents (including the proteinase K) is supplied from the same manufacturer, possibly even in the extraction kit. However, as we demonstrate here, individual labs can potentially gain significant improvements in yield and integrity by optimizing the proteinase K digest and deparaffinization steps, using the manufacturer’s recommendation as a starting point.

We used Qiagen’s QIAamp FFPE Tissue kit, where the manufacturer’s deparaffinization protocol was to use centrifuge tubes, their proteinase K volume to be set to 20 µl, and then perform the digest until the sample was completely lysed (i.e., the 20 µl/24 hr digest in our study). If we take the data that we obtained using this proteinase K protocol, in conjunction with tube deparaffinization, and then apply the QC acceptance threshold used for FFPE tissue in the pilot study for the 100,000 Genomes Project (400 ng DNA extracted with a ∆Cq less than 2.5 in the Illumina FFPE QC kit), we find that 33% of our extractions fail QC.6 (This is a very similar failure rate to the 31% reported for FFPE biospecimens in the aforementioned study.) Optimizing the proteinase K digest in respect of our biospecimens, our starting quantity (10 sections of 4 µm) and deparaffinization solution (Histoclear xylene substitute) enabled us to reduce the QC failure rate to 15% when tube deparaffinization was retained and then to 7% when slide deparaffinization was used.

Although performing slide deparaffinization is more laborious than tube deparaffinization in some respects (it is necessary to prepare the slides and then scrape the deparaffinized sections from the slides into tubes for the downstream proteinase K digest), it is less laborious in others: It is much faster to lift a rack of slides from a bath of one deparaffinization reagent and place it in a bath of another than it is to place tubes in a centrifuge, perform the centrifugation, unload the centrifuge, open each tube, pipette off the deparaffinization reagent, pipette in the next reagent, close the tubes, and then reload the centrifuge. Avoiding pipetting also means that there is no risk, when slide deparaffinization is used, that tissue (which is often difficult to see) will be aspirated into the pipette along with the reagent and thus lost to extraction.

We are aware of one previous study that compared deparaffinization in tubes with that on slides, using 16 FFPE dental follicle biospecimens.17 The authors (Senguven et al.) deparaffinized one section of 10 µm per method and found, as we did, that slide-deparaffinized sections had higher yields of dsDNA (assayed by Pico Green spectrofluorometry). However, they also report that slide-deparaffinized sections had lower concentrations of total nucleic acid (assayed by OD260 nm spectrophotometry) than tube-deparaffinized sections. We found the opposite result: Spectrophotometry concentrations were higher in slide-deparaffinized sections. Senguven et al. do not say that an RNase digest was included in their DNA extraction protocol, so the enriched “total nucleic acid” they report in tube-deparaffinized extractions could be RNA, which is known to coelute with DNA in the absence of an RNase digest and will absorb light at OD260 nm.9

We are aware of two previous publications that compare changes to the proteinase K protocol. In one, the authors found that DNA yields increased when the proteinase K digest time was increased from 3 hr to overnight in the majority of the eight kits they tested (demonstrating the general applicability of choosing the proteinase K protocol as a subject for optimization).18 Notably, the QIAamp kit that we used was one of the exceptions where no difference in yield was found. Our extension times were longer however (from 24 to 72 hr), which might explain the difference in our results.

In the second study, proteinase K digests of overnight and 72 hr were compared for sections deparaffinized in tubes and on slides, with the authors finding improved yields for both deparaffinization methods when the digest length was increased.17 We found that increasing the digest time was beneficial in terms of improving yield, so we concur with the previous studies, but we found that increasing the volume of proteinase K from 20 to 40 μl was a much more effective method of increasing yields.

The improvement in yield gained by increasing proteinase K volume was magnified in more cellular samples (>10,000 epithelial tumor cells/section). Given that all the samples in the same digest protocol had the same quantity of proteinase K, the enzyme-to-cell ratio would have been lower in more cellular samples. So, it is not surprising that improving that ratio by adding additional proteinase K generated improvements in yield. A further increase in yield was then gained when the deparaffinization was switched from tubes to slides, but only when the sections contained >50,000 epithelial tumor cells per section. Therefore, for sections containing ≤50,000 cells, switching the deparaffinization method made no difference to yield. This finding demonstrates that, in our experimental conditions, the deparaffinization method influences the proteinase K digestion, but only in more cellular samples.

The reason why only the epithelial tumor cells were counted was because this information was required for downstream sequencing (the purity of DNA with regard to the mutations of interest), and as such, these data were incidental to this study. We would also have purified DNA from uncounted stromal cells, but these would have contributed less to the overall yield because the stromal content was much lower. We found a very strong correlation between epithelial tumor cell count and DNA yield (χ2 = 0.84), and the R2 value in the linear regression equation could be interpreted to mean that tumor epithelial cellularity accounts for 60% of the DNA yield, but only when the protocol had been optimized. It is logical that both the correlation coefficient and the R2 value would be even higher if total cellularity was taken into account.

Given that all the blocks were of the same dimensions and we found a large variation in yield between the blocks, DNA yield cannot be predicted from tissue area alone; even when the protocol is fully optimized, cellularity must be used. The ability to predict DNA yield from cellularity can be useful in determining how many sections to use for an extraction, or how many extractions need to be performed, when a minimum yield threshold is required. However, our data show that such predictions can only be performed when the protocol has been fully optimized. Correlating DNA yield with cell count might therefore be a useful way of measuring how efficient a DNA extraction protocol is, with a lack of correlation suggesting an inefficient protocol. However, it is important to remember that we normalized fixation time in all of our samples, and we cannot be confident that predictions of yield based on cellularity will be accurate for tissue blocks in a routine clinical workflow, where the fixation times are inconsistent.

It is also important to make the point that it cannot be assumed that other laboratories will see an improvement of the same magnitude that we have done by increasing the volume of proteinase K and switching to slide deparaffinization. If fewer sections per extraction were used, there would be less paraffin to solubilize, and consequently tube deparaffinization might be equally effective. Alternatively, tube deparaffinization might become more efficient if the volume of deparaffinization reagents was increased in the tubes. If the gain in yield we found was (partially) a consequence of the tissue rehydration only applied to the slide-deparaffinized sections, a yield improvement in tube deparaffinization might also be achieved by adding a rehydration step in the tube deparaffinization protocol. Thus, we are advocating the principle that protocols should be optimized and suggesting the targets for that optimization; the precise protocol we describe here will not be optimal in all instances.

Integrity is critical in determining the usability of DNA. We used the Illumina FFPE QC Assay (qPCR), multiplex PCR, and DINs (i.e., nanoelectrophoresis) to assay DNA integrity. There was no correlation between the ∆Cq returned in the Illumina assay and DIN, which is a finding we reported in a previous study.19 Consequently, there is no consensus between the two DNA integrity assays as to which of the DNA extracts were of high (or low) integrity.

There was, however, a correlation between % dsDNA and ∆Cq, which was weak but statistically significant. The correlation was positive, so samples with higher % dsDNA also had higher ∆Cq (meaning lower integrity). The explanation for this counterintuitive result might lie in the quantification method for the Illumina assay. All samples in the assay are normalized in respect of their starting quantity using Pico Green spectrofluorometry (and therefore dsDNA only), so extractions with lower % dsDNA values will have a greater quantity of total DNA at the start of the qPCR reaction (the enriched and unquantified ssDNA). If some of those ssDNA was amplifiable in the PCR reaction, then it will lower the Cq, and therefore the ∆Cq, reducing the assay’s accuracy.

Unlike RNA integrity numbers in RNA extracted from FFPE tissue, DINs typically fall in the mid-range of the 1 to 10 scale, so DIN appears to be a suitable method for determining DNA integrity in FFPE tissues. However, it is possible that the extent of DNA integrity as determined by nanoelectrophoresis does not correspond with functionality in PCR. For example, the three DNA extractions that generated 100 and 200 bp but not 300 and 400 bp amplicons in multiplex PCR (so functional DNA was <300 bp in length) had DIN electropherograms that peaked in terms of DNA quantity at 2980, 584, and 2463 bp, and the extraction that could only generate a 100-bp amplicon had maximum quantity of DNA at 478 bp according to the DIN electropherogram.

Some projects maximize DNA yield and integrity by using fresh frozen tissue, which yields larger quantities of DNA that is less degraded than that obtained from FFPE biospecimens. However, in the clinical setting, FFPE tissue biospecimens, not frozen tissue specimens, are required, and consequently, the routine infrastructure that exists is geared specifically for FFPE biospecimens. Collecting, freezing, and then storing an additional biospecimen are logistically complicated and expensive, and sometimes impossible, as even when an efficient infrastructure is in place to do so, often there is insufficient material to provide a second biospecimen. It is noteworthy that in the pilot study for the 100,000 Genomes Project, where both frozen and FFPE biospecimens were collected for whole genome sequencing, 31% of the FFPE biospecimens failed QC on account of insufficient DNA yield and/or integrity, but 48% of patients had to be excluded because a frozen biospecimen could not be collected.6 We therefore argue that it makes sense to use FFPE rather than frozen biospecimens, but improve DNA yield and integrity by optimizing the extraction protocol as we have done here and then selecting downstream analytical platforms that are more amenable to FFPE tissue.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 2019-00183R1_Production_Supplemental_Table_1_online_supp for Effect of Different Proteinase K Digest Protocols and Deparaffinization Methods on Yield and Integrity of DNA Extracted From Formalin-fixed, Paraffin-embedded Tissue by Zoe Frazer, Changyoung Yoo, Manveer Sroya, Camille Bellora, Brian L. DeWitt, Ignacio Sanchez, Geraldine A. Thomas and William Mathieson in Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: ZF performed most of the lab work, but MS, IS, BLDW, and CB contributed. CY performed the cell counting. GAT conceived and planned the study. WM assisted in the planning of the study, performed the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded using generic internal funds of Imperial College London Tissue Bank and the Integrated Biobank of Luxembourg.

Contributor Information

Zoe Frazer, Department of Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College London, London, UK.

Changyoung Yoo, Department of Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College London, London, UK; Department of Pathology, The Catholic University of Korea, St. Vincent’s Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

Manveer Sroya, Department of Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College London, London, UK.

Camille Bellora, Integrated Biobank of Luxembourg, Dudelange, Luxembourg.

Brian L. DeWitt, Integrated Biobank of Luxembourg, Dudelange, Luxembourg

Ignacio Sanchez, Integrated Biobank of Luxembourg, Dudelange, Luxembourg.

Geraldine A. Thomas, Department of Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College London, London, UK

William Mathieson, Integrated Biobank of Luxembourg, Dudelange, Luxembourg.

Literature Cited

- 1. Astolfi A, Urbini M, Indio V, Nannini M, Genovese CG, Santini D, Saponara M, Mandrioli A, Ercolani G, Brandi G, Biasco G, Pantaleo MA. Whole exome sequencing (WES) on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). BMC Genomics. 2015;16:892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bonfiglio S, Vanni I, Rossella V, Truini A, Lazarevic D, Dal Bello MG, Alama A, Mora M, Rijavec E, Genova C, Cittaro D, Grossi F, Coco S. Performance comparison of two commercial human whole-exome capture systems on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded lung adenocarcinoma samples. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bonnet E, Moutet ML, Baulard C, Bacq-Daian D, Sandron F, Mesrob L, Fin B, Delepine M, Palomares MA, Jubin C, Blanche H, Meyer V, Boland A, Olaso R, Deleuze JF. Performance comparison of three DNA extraction kits on human whole-exome data from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded normal and tumor samples. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0195471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hedegaard J, Thorsen K, Lund MK, Hein AK, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Vang S, Nordentoft I, Birkenkamp-Demtroder K, Kruhoffer M, Hager H, Knudsen B, Andersen CL, Sorensen KD, Pedersen JS, Orntoft TF, Dyrskjot L. Next-generation sequencing of RNA and DNA isolated from paired fresh-frozen and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples of human cancer and normal tissue. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e98187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oh E, Choi YL, Kwon MJ, Kim RN, Kim YJ, Song JY, Jung KS, Shin YK. Comparison of accuracy of whole-exome sequencing with formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded and fresh frozen tissue samples. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0144162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Robbe P, Popitsch N, Knight SJL, Antoniou P, Becq J, He M, Kanapin A, Samsonova A, Vavoulis DV, Ross MT, Kingsbury Z, Cabes M, Ramos SDC, Page S, Dreau H, Ridout K, Jones LJ, Tuff-Lacey A, Henderson S, Mason J, Buffa FM, Verrill C, Maldonado-Perez D, Roxanis I, Collantes E, Browning L, Dhar S, Damato S, Davies S, Caulfield M, Bentley DR, Taylor JC, Turnbull C, Schuh A. Clinical whole-genome sequencing from routine formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens: pilot study for the 100,000 Genomes Project. Genet Med. 2018;20:1196–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hampel KJ, de Abreu FB, Sidiropoulos N, Peterson JD, Tsongalis GJ. Variant call concordance between two laboratory-developed, solid tumor targeted genomic profiling assays using distinct workflows and sequencing instruments. Exp Mol Pathol. 2017;102(2):215–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mathieson W, Marcon N, Antunes L, Ashford DA, Betsou F, Frasquilho SG, Kofanova OA, McKay SC, Pericleous S, Smith C, Unger KM, Zeller C, Thomas GA. A critical evaluation of the PAXgene tissue fixation system: morphology, immunohistochemistry, molecular biology, and proteomics. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;146(1):25–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sanchez I, Remm M, Frasquilho S, Betsou F, Mathieson W. How severely is DNA quantification hampered by RNA co-extraction? Biopreserv Biobank. 2015;13(5):320–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Beers EH, Joosse SA, Ligtenberg MJ, Fles R, Hogervorst FBL, Verhoef S, Nederlof PM. A multiplex PCR predictor for aCGH success of FFPE samples. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(2):333–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Serizawa M, Yokota T, Hosokawa A, Kusafuka K, Sugiyama T, Tsubosa Y, Yasui H, Nakajima T, Koh Y. The efficacy of uracil DNA glycosylase pretreatment in amplicon-based massively parallel sequencing with DNA extracted from archived formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded esophageal cancer tissues. Cancer Genet. 2015;208(9):415–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mathieson W, Thomas CA. Using FFPE tissue in genomic analyses: advantages, disadvantages and the role of biospecimen science. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2019;7:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spencer DH, Sehn JK, Abel HJ, Watson MA, Pfeifer JD, Duncavage EJ. Comparison of clinical targeted next-generation sequence data from formalin-fixed and fresh-frozen tissue specimens. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15(5):623–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nagahashi M, Shimada Y, Ichikawa H, Nakagawa S, Sato N, Kaneko K, Homma K, Kawasaki T, Kodama K, Lyle S, Takabe K, Wakai T. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sample conditions for deep next generation sequencing. J Surg Res. 2017;220:125–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schweiger MR, Kerick M, Timmermann B, Albrecht MW, Borodina T, Parkhomchuk D, Zatloukal K, Lehrach H. Genome-wide massively parallel sequencing of formaldehyde fixed-paraffin embedded (FFPE) tumor tissues for copy-number- and mutation-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(5):e5548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Greer CE, Wheeler CM, Manos MM. Sample preparation and PCR amplification from paraffin-embedded tissues. PCR Methods Appl. 1994;3(6):S113–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Senguven B, Baris E, Oygur T, Berktas M. Comparison of methods for the extraction of DNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded archival tissues. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11(5):494–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Janecka A, Adamczyk A, Gasinska A. Comparison of eight commercially available kits for DNA extraction from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Anal Biochem. 2015;476:8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mathieson W, Guljar N, Sanchez I, Sroya M, Thomas GA. Extracting DNA from FFPE tissue biospecimens using user-friendly automated technology: is there an impact on yield or quality? [published online ahead of print May 3, 2018]. Biopreserv Biobank. doi: 10.1089/bio.2018.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, 2019-00183R1_Production_Supplemental_Table_1_online_supp for Effect of Different Proteinase K Digest Protocols and Deparaffinization Methods on Yield and Integrity of DNA Extracted From Formalin-fixed, Paraffin-embedded Tissue by Zoe Frazer, Changyoung Yoo, Manveer Sroya, Camille Bellora, Brian L. DeWitt, Ignacio Sanchez, Geraldine A. Thomas and William Mathieson in Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry