Abstract

Studies show that gut microbial dysbiosis induced by chronic opioid use is linked to central opioid tolerance. Here, we suggest that a persistent decrease in gastrointestinal motility by opioids is a primary cause of gut microbial dysbiosis and that improving gastrointestinal transit might be a strategy in preventing opioid analgesic tolerance.

Studies on microbiome–gut–brain interactions have increased considerably to the point that many aspects of mental health have been linked to the gut microbiome, including anxiety, mood, depression and pain1. The mechanisms by which these centrally mediated conditions are modulated by the gut bacteria are unclear. Here, we discuss new evidence that the effect of chronic morphine treatment on gut motility alters the gut microbiome resulting in disruption of epithelial barrier integrity, bacterial translocation and release of inflammatory substances that modulate the effect of opioids in the brain to induce antinociceptive tolerance. In the context of the current opioid crisis, elucidating the role of the gut microbiome on the pharmacological properties of opioids provides an opportunity to discover potential therapeutic targets to alleviate the burden on society imposed by these otherwise excellent pain relievers.

Opioids have been known for centuries as perhaps the most effective analgesics. Although opioids are excellent analgesics, their euphoric effects enhance the propensity to abuse resulting in addiction. The potential for abuse with these drugs has resulted in an opioid crisis in which >115 people per day die due to opioid overdose in the USA (see Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) WONDER).

Overdosing with opioids is predicated by the fact that differential levels of tolerance develop with chronic use. Tolerance is characterized by a shift in the dose–response relationship such that increased doses are needed to provide an equivalent response. For addicts, the increased doses needed to achieve the desired euphoric effects after tolerance to the euphoria has developed can induce respiratory depression to a level that can be lethal. Our current understanding, on the basis of clinical and animal studies, is that tolerance to the analgesic and euphoric effects develops at a faster rate than tolerance to opioid-induced respiratory depression.

Conversely, little or no tolerance develops to the constipating effects of opioids. These effects are mediated by μ-opioid receptors expressed on enteric neurons that reduce neuronal excitability upon activation resulting in slowing of gut motility. In an Internet-based survey of 322 patients with chronic pain from the USA and Europe receiving opioid therapy and laxatives, 81% of patients reported opioid-induced constipation (OIC)2. However, the clinical management of patients with OIC, particularly for long-term opioid users, is limited by evidence gaps of the effectiveness of current therapies and in our understanding of the mechanisms for the development of tolerance to opioids.

Slowing of gastrointestinal transit by opioids substantially alters the gut microbiome, as noted in patients with constipation-predominant IBS3. Studies have also documented compositional shifts in the gut microbiota in individuals and patients using opioids. In individuals addicted to heroin, one study reported marked increases in diversity in the gut microbiota composition compared with healthy controls4. In patients with cirrhosis treated with opioids, microbial dysbiosis due to chronic opioid use was independent of the liver disease and resulted in increased endotoxaemia and hospital re-admissions5. A cross-sectional study of African-American men with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) demonstrated a significant interaction of opioid use with changes in the gut microbiome, including enhanced levels of Bifidobacterium in patients with T2DM with a history of opioid use disorder6. The effects on the gut microbiome with opioid use are also associated with worsening of gastrointestinal disease. For example, studies from the TREAT registry, comprising >6,000 patients with Crohn’s disease, suggest that opioid use was associated with a 1.5-fold increased risk of mortality from colonic inflammation and a threefold risk of infection compared with patients not receiving opioid analgesics7.

Preclinical studies also correlate with these findings8; for example, microbial dysbiosis is observed in mice receiving chronic morphine treatment. The bacterial populations that are altered with chronic morphine treatment included increases in the abundance of Staphylococcus, Enterococcus and Proteobacteria, and decreases in the abundance of Bacteriodales, Clostridiales and Lactobacillales. Associated with the opioid-induced changes in the gut microbiome were a loss of epithelial integrity, bacterial translocation and increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β in the colonic tissues8. Interestingly, depletion of the gut bacteria in mice with antibiotics prevented the development of tolerance to chronic morphine treatment9, suggesting that the sequence of events resulting from changes in the microbiome to development of an inflammatory state might lead to tolerance to the antinociceptive effects of morphine.

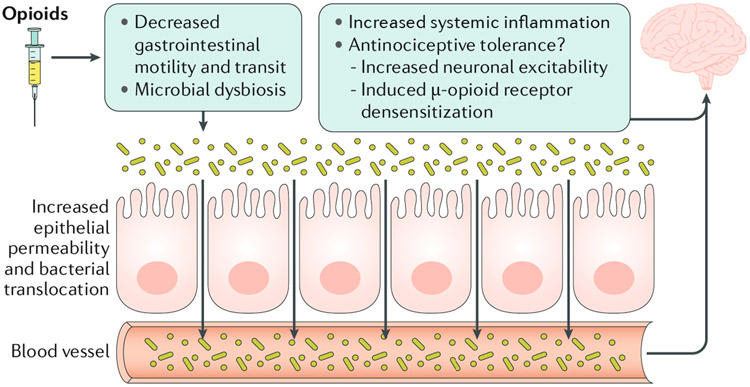

The mechanism or mechanisms for how the inflammatory response originating in the gut results in antinociceptive tolerance to chronic morphine use remain unclear, but suggest an important link between the gut and central effects of opioids. Studies have suggested that opioid activation of non-neuronal cells including microglia and astrocytes results in a pro-inflammatory environment that can promote tolerance, thereby mitigating opioid efficacy, probably due to enhanced excitability of neurons by inflammatory mediators10. Systemic inflammatory factors originating in the gut might result in central effects through a compromised blood-brain barrier caused by chronic opioid use10. Colonic supernatants from chronic-morphine-treated mice were found to desensitize μ-opioid receptors in the dorsal root ganglia neurons, suggesting that factors released from the colonic wall following chronic morphine treatment affect μ-opioid receptor desensitization9. We therefore posit that the decrease in gut motility with chronic opioid use might be a primary effect for the development of long-term analgesic tolerance via changes in the gut microbiome (FIG. 1).

Fig. 1 ∣. Antinociceptive tolerance to opioids through changes in the gut microbiota.

Chronic opioid treatment reduces gastrointestinal transit via effects on μ-opioid receptors, resulting in an altered microbiome. Changes in the microbiome disrupt epithelial permeability enabling bacterial translocation and systemic inflammation that could enhance the development of antinociceptive tolerance. Inflammatory mediators might potentially translocate through a ‘leaky’ blood–brain barrier, and either increase neuronal excitability to mitigate opioid effects or directly induce μ-opioid receptor desensitization resulting in tolerance.

Thus, enhancing gastrointestinal transit could be a strategy to prevent the induction of chronic opioid tolerance. In this context, treatment with short-chain fatty acids (acetate, propionate and butyrate) might be of potential benefit. It is well-documented that butyrate not only maintains gut epithelial integrity but also enhances colonic motility either directly via activation of GPR43 on intestinal smooth muscle or indirectly through activation of enteric reflex pathways. Levels of butyrate are reduced by the peripheral μ-opioid receptor agonist and anti-diarrhoeal agent loperamide as a result of a decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria3. Oral treatment with butyrate was also found to prevent morphine antinociceptive tolerance in mice treated with chronic morphine (H.I.A., unpublished data). A potential approach to prevent induction of morphine tolerance might, therefore, involve treatment with butyrate in conjunction with opioid treatment.

The mechanisms for the development of opioid tolerance are complex and vary between different tissues. In the current opioid crisis, the need for alternative therapies has become more important. The mechanisms of desensitization of the μ-opioid receptor by chronic morphine use have been studied for many years and involves multiple signalling pathways. However, the mechanism for the development of long-term tolerance is unclear but might involve changes in the gut microbiome initiated by slowing of the gut transit by opioids. A focus on the pathophysiology of the gut by opioids therefore merits further consideration.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DA036975.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

RELATED LINKS

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) WONDER: http://wonder.cdc.gov

References

- 1.Scriven M et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders: influence of gut microbe to brain signalling. Diseases 6, 78 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell TJ et al. The prevalence, severity, and impact of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: results of a US and European Patient Survey (PROBE 1). Pain Med. 10, 35–42 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Touw K et al. Mutual reinforcement of pathophysiological host-microbe interactions in intestinal stasis models. Physiol. Rep 5, e13182 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu Y et al. Bacterial diversity of intestinal microbiota in patients with substance use disorders revealed by 16S rRNA gene deep sequencing. Sci. Rep 7, 3628 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acharya C et al. Chronic opioid use is associated with altered gut microbiota and predicts readmissions in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther 45, 319–331 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barengolts E et al. Gut microbiota varies by opioid use, circulating leptin and oxytocin in African American men with diabetes and high burden of chronic disease. PLOS ONE 13, e0194171 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtenstein GR et al. Serious infection and mortality in patients with Crohn’s disease: more than 5 years of follow-up in the TREAT registry. Am. J. Gastroenterol 107, 1409–1422 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akbarali HI & Dewey WL The gut-brain interaction in opioid tolerance. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 37, 126–130 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mischel RA, Dewey WL & Akbarali HI Tolerance to morphine-induced inhibition of TTX-R sodium channels in dorsal root ganglia neurons is modulated by gut-derived mediators. iScience 2, 193–209 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutchinson MR et al. Exploring the neuroimmunopharmacology of opioids: an integrative review of mechanisms of central immune signaling and their implications for opioid analgesia. Pharmacol. Rev 63, 772–810 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]