Abstract

Background

Oligohydramnios (reduced amniotic fluid) may be responsible for malpresentation problems, umbilical cord compression, concentration of meconium in the liquor, and difficult or failed external cephalic version. Simple maternal hydration has been suggested as a way of increasing amniotic fluid volume in order to reduce some of these problems.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the effects of maternal hydration on amniotic fluid volume and measures of pregnancy outcome.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (June 2009).

Selection criteria

Randomised trials comparing maternal hydration with no hydration in pregnant women with reduced or normal amniotic fluid volume.

Data collection and analysis

Eligibility and trial quality were assessed by both review authors.

Main results

Four studies of 122 women were included. The women were asked to drink two litres of water before having a repeat ultrasound examination. Maternal hydration in women with and without oligohydramnios was associated with an increase in amniotic volume (mean difference (MD) for women with oligohydramnios 2.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.43 to 2.60; and MD for women with normal amniotic fluid volume 4.50, 95% CI 2.92 to 6.08). Intravenous hypotonic hydration in women with oligohydramnios was associated with an increase in amniotic fluid volume (MD 1.35, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.10). Isotonic intravenous hydration had no measurable effect. No clinically important outcomes were assessed in any of the trials.

Authors' conclusions

Simple maternal hydration appears to increase amniotic fluid volume and may be beneficial in the management of oligohydramnios and prevention of oligohydramnios during labour or prior to external cephalic version. Controlled trials are needed to assess the clinical benefits and possible risks of maternal hydration for specific clinical purposes.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Pregnancy, Amniotic Fluid, Fluid Therapy, Oligohydramnios, Oligohydramnios/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Maternal hydration for increasing amniotic fluid volume in oligohydramnios and normal amniotic fluid volume

Pregnant women with too little fluid surrounding their babies can increase this by consuming liquid, although it is not known whether this improves outcomes.

Oligohydramnios is where there is too little fluid surrounding the baby in the womb (uterus). This may occur because the baby is not thriving properly. It may cause the baby to be unable to turn into the head down position for the birth, or compression of the baby's umbilical cord. The review of four trials (122 women) found that women who drank extra water (usually two litres over two hours) or had fluid dripped directly into their bloodstream (both forms of maternal hydration) increased the volume of the fluid surrounding the baby. However, it is not clear whether this is better for the baby or not. More research is needed.

Background

Oligohydramnios (reduced amount of fluid surrounding the baby) may be caused by problems such as placental insufficiency, fetal urinary tract anomalies and chronic amniotic fluid leakage. Irrespective of the cause, oligohydramnios may be responsible for problems such as malpresentation (particularly breech presentation), umbilical cord compression (Gabbe 1976), concentration of meconium in the liquor, difficult or failed external cephalic version (manipulating the baby from breech presentation to cephalic (head first) presentation) (Benifla 1995), difficult ultrasound visualisation, and if extreme and early in pregnancy, impaired fetal lung development (pulmonary hypoplasia). Pulmonary hypoplasia, if severe, is usually fatal. Umbilical cord compression during labour may lead to fetal heart rate decelerations and an increased chance of caesarean section, which is reduced by infusing additional fluid into the uterus through a catheter inserted through the cervix (amnioinfusion) (Hofmeyr 1998). Artificial augmentation of amniotic fluid volume by amnioinfusion in labour has been shown to be effective in a number of situations (Hofmeyr 1996a; Hofmeyr 1998; Hofmeyr 2002; Hofmeyr 1996b; Hofmeyr 2001d). Transabdominal amnioinfusion has been suggested during pregnancy to improve ultrasound visualisation in oligohydramnios, to correct extreme oligohydramnios to reduce the risk to fetal lung development, and to facilitate external cephalic version (Benifla 1995; Fisk 1991). Maternal hydration may theoretically increase amniotic fluid volume by causing fetal diuresis. An effective, non‐invasive method of increasing amniotic fluid volume may have several applications in obstetric practice. Most of these would relate to oligohydramnios, but increased volume in women with normal amniotic fluid might also be useful to facilitate external cephalic version.

Objectives

To assess the effects of maternal hydration on amniotic fluid volume and fetal well being.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Clinical trials comparing the effect of maternal hydration, with a control group (no hydration); random allocation to treatment and control groups, with adequate allocation concealment; violations of allocated management and exclusions after allocation not sufficient to materially affect outcomes.

Types of participants

Pregnant women with oligohydramnios or normal amniotic fluid volume.

Types of interventions

Maternal hydration (oral or intravenous), compared with no hydration.

Types of outcome measures

Amniotic fluid volume increase, fetal parameters such as fetal heart rate decelerations, obstetric interventions, perinatal outcomes, maternal assessment of therapy (see table of comparisons).

Outcomes included if reasonable measures taken to minimise observer bias; missing data insufficient to materially influence conclusions; data available for analysis according to original allocation, irrespective of protocol violations; data available in a format suitable for analysis.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (June 2009).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeAppendix 1.

For this update, we used the following methods when assessing the trials identified by the updated search (Lorzadeh 2005; Malhotra 2002; Trivedi 2005; Yan‐Rosenberg 2007).

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We would resolve any disagreement through discussion or, if required, by consulting the relevant editor.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We would resolve discrepancies through discussion or, if required, by consulting the relevant editor. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). Any disagreement would be resolved by discussion or by involving the relevant editor.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

adequate (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

inadequate (any non random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. Studies were judged at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate, inadequate or unclear for participants;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for personnel;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for outcome assessors

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook. We assessed methods as:

adequate (< 10% loss);

inadequate:

unclear

(5) Selective reporting bias

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (where it was clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review had been reported);

inadequate (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes had been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear.

(6) Other sources of bias

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

yes;

no;

unclear.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2008). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. We would explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

Cluster‐randomised trials and crossover trials were considered unlikely to be relevant to this review

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, levels of attrition were noted. The impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect were explored by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (I² > 50%) we would explore it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspected reporting bias (see ‘Selective reporting bias’ above), we would attempt to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data. Where this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results would be explored by a sensitivity analysis.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). We used fixed‐effect inverse variance meta‐analysis for combining data where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. Where we suspected clinical or methodological heterogeneity between studies sufficient to suggest that treatment effects may differ between trials we would use random‐effects meta‐analysis.

If substantial heterogeneity was identified in a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis this would be noted and the analysis repeated using a random‐effects method.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not plan to carry out subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We would carry out sensitivity analysis to assess the effect of including trials with greater risk of bias, if there were sufficient trials.

Results

Description of studies

See table of Characteristics of included studies.

Four studies (122 women) met the pre‐stated criteria. In studies of women with oligohydramnios (Doi 1998; Kilpatrick 1991), women in the treatment group were asked to drink two litres of water over two hours one to four hours before repeat ultrasound examination the next day or they were given hypotonic saline solution (1/2 normal saline) at a rate of 1000 mL per hour over two hours in treatment group and 10 mL per hour in control group and amniotic fluid index was checked an hour later (Yan‐Rosenberg 2007). In the study of women with normal amniotic fluid (Kilpatrick 1993), the treatment group were asked to drink two litres of water while the control group were asked to drink 100 ml, and ultrasound examination was repeated four to six hours later.

Risk of bias in included studies

See table of Characteristics of included studies.

Women with oligohydramnios were allocated 'randomly' to treatment and control groups (Doi 1998; Kilpatrick 1991). For random allocation of women with normal amniotic fluid volumes (Kilpatrick 1993) opaque envelopes were used. The studies appeared to be methodologically sound.

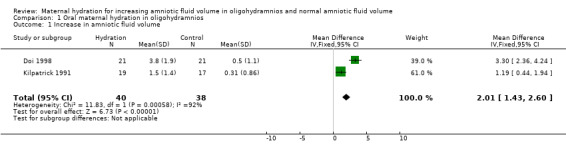

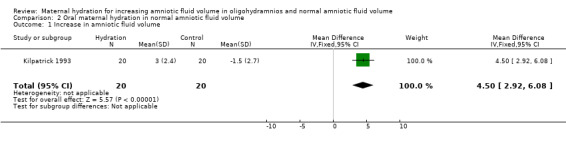

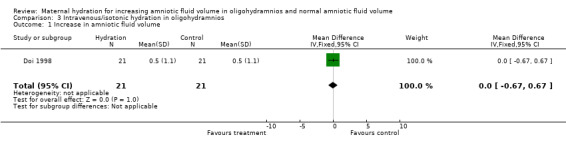

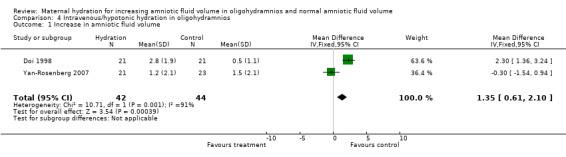

Effects of interventions

The amniotic fluid index was significantly increased in the treatment group compared with the control group in both the studies of women with oligohydramnios (two studies, 78 women; mean difference (MD) 2.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.43 to 2.60) (Doi 1998; Kilpatrick 1991) and normal amniotic fluid volume (one study, 40 women; MD 4.50, 95% CI 2.92 to 6.08) (Kilpatrick 1993). Doi 1998 compared intravenous isotonic and hypotonic fluid infusions as well as oral hydration. Hypotonic and isotonic infusions did not increase the amniotic fluid volume at a level similar to that of oral hydration (two trials, 86 women; MD 1.35, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.10). No adverse effects on the mother or infant have been reported in the four studies included in this review.

Discussion

In view of the many obstetric situations in which reduced amniotic fluid volume may pose problems, particularly for the fetus, the possibility of increasing amniotic fluid volume with a simple, inexpensive method such as maternal hydration may have useful clinical applications. However, clinical outcomes were not assessed in these trials. Drinking two litres of water in a relatively short period of time may be unpleasant and difficult for women too. None of the studies reported any maternal satisfaction information. Perhaps if the mother experiences difficulties hydration can be spread over a longer time.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

As the studies reviewed have not assessed clinically relevant outcomes or possible complications, there is no evidence to support the use of maternal hydration in routine practice, except in the framework of further clinical trials designed to address these issues.

Implications for research.

The studies reviewed have shown in principle that amniotic fluid volume may be increased by maternal hydration. Because maternal hydration is simple and inexpensive, trials to investigate its effectiveness in oligohydramnios in terms of clinically important outcomes such as fetal heart rate decelerations and in the case of extreme oligohydramnios, lung development, and assessing potential dangers such as electrolyte disturbance if used over an extended period, are worthwhile. The use of maternal hydration prior to external cephalic version at term also is worth investigating. In the light of the data reviewed here, the possible negative effect of starvation during labour on amniotic fluid level requires investigation (Hofmeyr 1999).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 January 2012 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1995 Review first published: Issue 1, 1995

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 October 2009 | New search has been performed | Search updated. Three trial reports added to Excluded studies (Lorzadeh 2005; Malhotra 2002; Trivedi 2005). One trial (Yan‐Rosenberg 2007) (two reports) added to Included studies in this updated review. |

| 18 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 27 January 2004 | New search has been performed | Search rerun but no new trials identified. |

| 1 September 2001 | New search has been performed | Repeat literature search revealed one trial of oral hydration for oligohydramnios (Deka 2001), which was excluded because it was not described as a randomised trial. |

Acknowledgements

None.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methods used to assess trials included in previous versions of this review

The following methods were used to assess Doi 1998; Kilpatrick 1991; Kilpatrick 1993.

Trials under consideration were evaluated for methodological quality and appropriateness for inclusion according to the prestated selection criteria, without consideration of their results. Individual outcome data were included in the analysis if they met the prestated criteria in Types of outcome measures. Included trial data were processed as described in Clarke 2001.

Data were extracted from the sources and entered onto the Review Manager (RevMan 2000) computer software, checked for accuracy, and analysed as above using the RevMan software. Continuous data were pooled using weighted mean differences and 95% confidence intervals.

Data and analyses

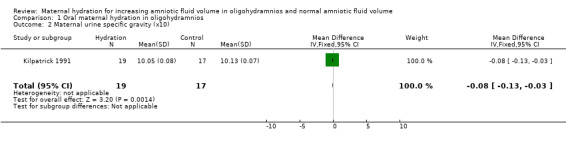

Comparison 1. Oral maternal hydration in oligohydramnios.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Increase in amniotic fluid volume | 2 | 78 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.01 [1.43, 2.60] |

| 2 Maternal urine specific gravity (x10) | 1 | 36 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.13, ‐0.03] |

| 3 Fetal heart rate decelerations | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Maternal electrolyte disturbance | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Enrolment‐delivery interval | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Assisted vaginal delivery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Caesarean section | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 5‐minute Apgar score < 7 | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Umbilical artery pH < 7.2 | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Neonatal encephalopathy | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Serious neonatal morbidity or death | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12 Mother not satisfied | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral maternal hydration in oligohydramnios, Outcome 1 Increase in amniotic fluid volume.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral maternal hydration in oligohydramnios, Outcome 2 Maternal urine specific gravity (x10).

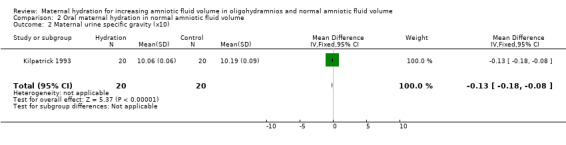

Comparison 2. Oral maternal hydration in normal amniotic fluid volume.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Increase in amniotic fluid volume | 1 | 40 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.5 [2.92, 6.08] |

| 2 Maternal urine specific gravity (x10) | 1 | 40 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.13 [‐0.18, ‐0.08] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oral maternal hydration in normal amniotic fluid volume, Outcome 1 Increase in amniotic fluid volume.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oral maternal hydration in normal amniotic fluid volume, Outcome 2 Maternal urine specific gravity (x10).

Comparison 3. Intravenous/isotonic hydration in oligohydramnios.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Increase in amniotic fluid volume | 1 | 42 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.67, 0.67] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Intravenous/isotonic hydration in oligohydramnios, Outcome 1 Increase in amniotic fluid volume.

Comparison 4. Intravenous/hypotonic hydration in oligohydramnios.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Increase in amniotic fluid volume | 2 | 86 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.61, 2.10] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Intravenous/hypotonic hydration in oligohydramnios, Outcome 1 Increase in amniotic fluid volume.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Doi 1998.

| Methods | Randomised, sealed envelopes used for allocation. Numbering or sequential opening are not mentioned. Outcome assessments were blinded. | |

| Participants | 84 women with low amniotic fluid index and gestational age more than 35 weeks. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: intravenous infusion of 2 litres of Ringer lactate over 2 hours (isotonic). Group 2: intravenous infusion of 2 litres of diluted Ringer lactate over 2 hours (hypotonic). Group 3: oral intake of 2 litres of water over 2 hours. Group 4: control group. | |

| Outcomes | Change in amniotic fluid index, blood chemistry. | |

| Notes | Power calculation reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

Kilpatrick 1991.

| Methods | Randomised by card selection. | |

| Participants | Women with oligohydramnios (amniotic fluid index 2.1‐6 cm); no indication for delivery; membranes intact; biophysical profile at least 8/10 or contraction stress test negative (women with amniotic fluid index 5.0 cm or less). | |

| Interventions | Women asked to drink 2 litres of water 2‐4 hours before repeat ultrasound examination on the same or the next day (n = 20), compared with controls, who were asked to drink their normal amount of fluid, and in the last 10 women an extra 100 ml (n = 20). | |

| Outcomes | Change in amniotic fluid index; maternal urine specific gravity. | |

| Notes | Observer blinded to group allocation. 1 woman in the hydration group excluded because of indomethacin therapy; 2 in the control group excluded because of drinking at least 2 litres of water, and one because of receiving an intravenous infusion. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Inadequate. |

Kilpatrick 1993.

| Methods | Allocation using opaque envelopes which were randomly mixed, then numbered consecutively. | |

| Participants | Women with normal amniotic fluid volume; no known pregnancy complications; > 28 weeks' gestation; singleton pregnancy; no ruptured membranes. | |

| Interventions | Women asked to drink 2 litres of water over 2 hours and re‐examined 2‐5 hours later (n = 20), compared with control group asked to drink 100 ml water (n = 20). | |

| Outcomes | Increase in amniotic fluid volume; maternal urine specific gravity. | |

| Notes | Observer blinded to group allocation. There appeared to be no losses to follow up. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

Yan‐Rosenberg 2007.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled. | |

| Participants | Women with singleton pregnancy between 37 and 42 weeks of gestation with AFI < 6 with no maternal and no fetal complications. | |

| Interventions | Treatment group ‐ women received IV infusion of 1/2 NS at 1L/h for 2 hours. Control group ‐ received IV infusion of 1/2 NS at 10 mL/h. |

|

| Outcomes | AFI was re‐assessed by a sonographer at 1 hour after the infusion was stopped. | |

| Notes | Power calculation done. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computerised programme used. |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Sealed cards used. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | All the infusion bags were covered by the nurse with paper bags, insuring that both the patient and the examiner were blinded to the randomisation results. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Data were complete. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All data were reported. |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

AFI: amniotic fluid index IV: intravenous

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Chelmow 1996 | Excluded because data not available in a format suitable for meta‐analysis. 13 non‐labouring women at 24‐37 weeks' gestation with documented ruptured membranes were 'randomised' to an intravenous fluid bolus with 1 litre of normal saline administered over 30 minutes (n = 6) versus no hydration (n = 7). All women had baseline AFI measured. The same blinded examiner repeated the examination 90 minutes later. The groups were similar in age, gravidity, parity, time since rupture, gestational age, and baseline AFI. In the hydration group, the AFI increased 5.1 cm (95% CI 2.9 to 7.3) after the fluid bolus. In the no‐hydration group, the change was 0.6 cm (95% CI, 1.1 to 2.2). The difference in the change in AFI between groups was 4.5 cm (95% CI, 1.3 to 7.7) (P = .008). |

| Deka 2001 | Excluded because allocation does not appear to have been randomised. 25 women with oligohydramnios (AFI < 8 cm) received oral hydration with 2 l water over 1 hour, and 25 women with oligohydramnios were taken as controls. AFI after hydration increased from a mean value of 6.99, SD 1.62 cm, to 10.48, SD 4.96cm (P < 0.001). In the control group there was a non‐significant decrease by 0.42, SD 0.71 cm. |

| Kerr 1996 | Published only as an abstract. Data are not presented in a suitable form for analysis. 50 patients with normal AFI undergoing antenatal testing were randomised to a hydration (oral water 1l /1 hour) or control (150 ml water). |

| Lorzadeh 2005 | Published only as an abstract. It is unclear whether the study was randomised. |

| Malhotra 2002 | It is unclear of the study was randomised. |

| Trivedi 2005 | Published only abstract. Randomisation not mentioned. |

AFI: amniotic fluid index CI: confidence interval SD: standard deviation

Differences between protocol and review

The original protocol has been updated with current methodology as described above.

Contributions of authors

GJ Hofmeyr prepared the original version, and is responsible for maintaining the review. AM Gülmezoglu quality‐checked and revised the review, and N Novikova prepared the first version of the current update.

Sources of support

Internal sources

University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa.

The Harold Katz Fund, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa.

HRP‐UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/WORLD BANK Special Programme in Human Reproduction, Geneva, Switzerland.

External sources

South African Medical Research Council, South Africa.

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Doi 1998 {published data only}

- Doi S, Osada H, Itoh K, Ikeda K, Sekiya S, Takehisa T. Effect of maternal hydration on oligohydramnios: a comparison of three volume expansion methods [abstract]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1998;178(1 Pt 2):S156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi S, Osada H, Seki K, Sekiya S. Effect of maternal hydration on oligohydramnios: a comparison of three volume expansion methods. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1998;92:525‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kilpatrick 1991 {published data only}

- Kilpatrick SJ, Safford K, Pomeroy T, Hoedt L, Scheerer L, Laros RK. Maternal hydration affects amniotic fluid index (AFI). American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1991;164:361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick SJ, Safford KL, Pomeroy T, Hoedt L, Scheerer L, Laros RK. Maternal hydration increases amniotic fluid index. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1991;78:1098‐102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kilpatrick 1993 {published data only}

- Kilpatrick SJ, Safford SJ. Maternal hydration increases amniotic fluid index in women with normal amniotic fluid. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1993;81:49‐52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yan‐Rosenberg 2007 {published data only}

- Yan‐Rosenberg L, Burt B, Bombard AT, Callado‐Khoury F, Sharett L, Julliard K, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing the effect of maternal intravenous hydration and placebo on the amniotic fluid index in oligohydramnios. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 2007;20(10):715‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan‐Rosenberg, Burt S, Collado‐Khoury, Sharet L, Bombard A, Weiner Z. Effect of maternal hydration on the AFI in women with oligohydramnios [abstract]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2005;193(6 Suppl):S101. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Chelmow 1996 {published data only}

- Chelmow D, Baker ER, Jones L. Maternal intravenous hydration and amniotic fluid index in patients with preterm ruptured membranes. Journal of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation 1996;3:127‐30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deka 2001 {published data only}

- Deka D, Malhotra B. Role of maternal oral hydration in increasing amniotic fluid volume in pregnant women with oligohydramnios. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2001;73:155‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kerr 1996 {published data only}

- Kerr J, Borgida AF, Hardardottir H, Calhoun S, Galetta J, Egan JFX. Maternal hydration and its effect on the amniotic fluid index [abstract]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1996;174(1 Pt 2):416. [Google Scholar]

Lorzadeh 2005 {published data only}

- Lorzadeh N, Najafi S, Parsa M, Kasemirad C. Effect of maternal hydration on amniotic fluid index. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2005;26(4):370. [Google Scholar]

Malhotra 2002 {published data only}

- Malhotra B, Deka D. Maternal oral hydration with hypotonic solution (water) increases amniotic fluid volume in pregnancy. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India 2002;52(1):49‐51. [Google Scholar]

Trivedi 2005 {published data only}

- Trivedi KK, Trivedi KK. Liquid endosperm of coconut consumed orally increases amniotic fluid in oligohydramnios. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2005;105(4 Suppl):35S. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Benifla 1995

- Benifla JL, Goffinet F, Bascou V, Darai E, Proust A, Madelenat P. Transabdominal amnio‐infusion facilitates external version manouver after initial failure (translation). Journal de Gynecologie, Obstetrique et Biologie de la Reproduction (Paris) 1995;24:319‐22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clarke 2001

- Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.1 [updated December 2000]. In: The Cochrane Library [database on CDROM]. The Cochrane Collaboration. Oxford: Update Software; 2000, issue 4.

Fisk 1991

- Fisk NM, Ronderos‐Dumit D, Soliani A, Nicolini U, Vaughan J, Rodeck CH. Diagnostic and therapeutic transabdominal amnioinfusion in oligohydramnios. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1991;78(2):270‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gabbe 1976

- Gabbe SG, Ettinger BB, Freeman RK, Martin CB. Umbilical cord compression associated with amniotomy: laboratory observations. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1976;126:353‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2008

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1 [updated September 2008]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hofmeyr 1996a

- Hofmeyr GJ, Gulmezoglu AM, Nikodem VC, Jager M. Amnioinfusion. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 1996;64:159‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hofmeyr 1996b

- Hofmeyr GJ. Prophylactic versus therapeutic amnioinfusion for oligohydramnios in labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1996, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000176] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hofmeyr 1998

- Hofmeyr GJ. Amnioinfusion for potential or suspected umbilical cord compression in labour.. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1998, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000013] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hofmeyr 1999

- Hofmeyr GJ, Scott F, Schalkwyk C, Nikodem VC. Hydration during labour‐‐a recipe. South African Medical Journal 1999;89:102‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hofmeyr 2001d

- Hofmeyr GJ. Amnioinfusion for preterm rupture of membranes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1998, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000942] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hofmeyr 2002

- Hofmeyr GJ. Amnioinfusion for meconium‐stained liquor in labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000014] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2000 [Computer program]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 4.1 for Windows. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

RevMan 2008 [Computer program]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.0. Copenhagen, The Nordic Cochrane Centre: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

References to other published versions of this review

Hofmery 2002

- Hofmeyr GJ, Gülmezoglu AM. Maternal hydration for increasing amniotic fluid volume in oligohydramnios and normal amniotic fluid volume. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000134] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]