Abstract

Accumulation of different protein–surfactant mixtures affords further knowledge about the structure–property interactions of biomacromolecules. They will help design suitable surfactants, which, in turn, can enhance the utilization of protein–surfactant complexes in biotechnologies, cosmetics, and food industry realms. Owing to their adaptable and remarkably notable properties, we are describing herein the interaction of Cm-E2O-Cm gemini surfactants (m = 12, 14, and 16) with α-CHT by employing various spectroscopic techniques including with molecular docking and density functional theory (DFT) method. Results have revealed complex formation, unfolding, and a static quenching mechanism in the interaction of gemini surfactants with α-CHT. The Stern–Volmer constant (KSV), quenching constant (kq), the number of binding sites (n), and binding constant (Kb) were interrogated by utilizing the fluorescence quenching method, UV–vis, synchronous, 3-D, and resonance Rayleigh scattering fluorescence studies. The data perceive the α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm complex formation along with conformational alterations induced in α-CHT. The contribution of aromatic residues to a nonpolar environment is illustrated by pyrene fluorescence. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and circular dichroism outcomes reveal conformational modifications in the secondary structure of α-CHT with the permutation of gemini surfactants. The computational calculations (molecular docking and DFT) further corroborate the complex formation between α-CHT and Cm-E2O-Cm gemini surfactants and the contribution of electrostatic/hydrophobic interaction forces therein.

1. Introduction

Much interest has been paid in the last few decades to the protein complexation with different small molecules that alter the structure and function of biological macromolecules.1−3 Such interactions can be utilized to develop synthetic chaperones for protein refolding and biomedicine as well as in a number of areas including analytical molecular biology, food, pharmacological, and cosmetic industries, drug delivery, design of nanocapsules, development of catalysts, etc.2−6 Furthermore, scientists are utilizing protein–surfactant complexes to design fluorescence sensors.7,8 In aqueous medium, ambiphilic molecules self-assemble into micelles or microstructures, which provide hydrophobic centers for encapsulating fluorophores noncovalently.9 Therefore, protein–surfactant interactions can stimulate modifications in the fluorescence emission properties of the encapsulated guest fluorophores. Hence, the mechanistic scenario of the interaction between proteins and surfactants is still viewed as a challenging and interactable study area. Consequently, this inspiration offers ample space for further exploration of these molecular interactions and to unveil the relationship between the concerned specific and nonspecific forces.

The serine proteinases are commonly distributed in nature, where they conduct a wide range of various utilities.10,11 Several proteinases emerge as realms in abundant multifunctional proteins, but others are independent small peptide chains. Bacterial serine proteinases share the α-chymotrypsin (α-CHT)-like bilobal β-barrel structure; however, owing to their shorter sequences and structural variances in surface loops, they are mostly distantly linked. The α-CHT belongs to the S1 family, which is one of the most prevalent serine protease families. It is an essential component of mammalian digestive systems, where it eventually breaks large protein molecules into smaller molecules that can be digested by suitable enzymes for further digestion by other proteolytic enzymes. The α-CHT preferably cleaves peptide bonds that involve the carboxyl groups of the aromatic amino acid residues, that is, tyrosine (Tyr), phenylalanine (Phe), and tryptophan (Trp). Scheme 1d demonstrates that the three-polypeptide chains (A, B, and C) of the α-CHT are joined by five inter- and intradisulfide bonds. The α-CHT consists of 245 amino acids and also contains a catalytic triad (His57, Asp102, and Ser195), which is part of the second domain and is a reactive group. The α-CHT also catalyzes the hydrolysis of amides and esters of aromatic amino acids, although much slower than peptide bonds. Also, the proteolytic enzyme α-CHT has a prospect to get utilized in biological and industrial areas.12

Scheme 1. Chemical Structures of Cationic Cm-E2O-Cm Gemini Surfactants (m = (a) 12, (b) 14, and (c) 16) and (d) Crystallographic Structure of α-Chymotrypsin.

These days, the gemini surfactants are drawing attention as next-generation surfactants. Having two polar headgroups covalently associated by a spacer group and two hydrophobic chains, the geminis have numerous characteristic aggregation properties better than the traditional single-chain surfactants, which involve deficient critical micelle concentration (CMC), considerable dependency on the spacer structure, unusual aggregate morphology, strong hydrophobic microdomains, etc.13 As regard to the interactions of cationic gemini surfactants with proteins, they also are more proficient with proteins, in contrast with traditional single-chain surfactants.14−17 Moreover, the consistently expanding ecological concerns of both consumers and legislation have impelled scientists’ interest in developing more eco-friendly surfactants. The majority of overall gemini surfactants have been reported to be toxic to marine life; therefore, their cytotoxicity is another crucial factor to be proposed. The surfactants have also been considered to persist in the soil after they are utilized and cause challenges due to their low rate of degradation, which, in turn, results in higher cleaning costs and other noteworthy expenditures.18−20

Because of all these necessities, our research team has synthesized a new series of ester-functionalized cationic gemini surfactants,21 assigned as Cm-E2O-Cm (where m = 12, 14, and 16 represent the number of carbon atoms in the hydrophobic chains of geminis and E2O is the betaine ester-type spacer). The designated geminis are novel because they satisfy most of the previously mentioned necessities in a molecule21,22 and have exceptionally excellent physicochemical characteristics, in contrast with the predominant gemini surfactants. Due to the presence of cleavable spacer in their effectively designed structure, the concerned surfactants provide a progressively broader scope for exposing their unpopulated projects in fields such as the environment, biochemistry, biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, etc. Therefore, unveiling and assessing the use of Cm-E2O-Cm geminis as prospective options to the conventional surfactants in various fields are of great concern.

To mitigate such concerns, surfactants that are readily cleavable suit the perfect option. Consequently, herein assigned surfactants could be an adequate alternative (in the future). Moreover, there is no report on the α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm interactions to date in the literature. Different biophysical methodologies, namely, fluorescence spectroscopy (intrinsic, extrinsic, three-dimensional, synchronous, and resonance Rayleigh scattering fluorescence), circular dichroism spectroscopy, UV–vis spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), molecular docking, and DFT, were utilized to explore the interactions between α-CHT and Cm-E2O-Cm gemini surfactants. This investigation will assist in scheming and accumulation of protein–surfactant complexes for their utilization in pharmaceutical and industrial areas. It will, moreover, address and enhance the impact of gemini structure on the reliability of proteins.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Identifications on the Conformational Changes of α-CHT

To determine the conformational alterations of α-CHT after dealing with geminis, we have used UV–vis absorption, synchronous fluorescence, FT-IR, three-dimensional fluorescence spectroscopy, circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, and resonance Rayleigh scattering (RRS) fluorescence to clarify the interaction between α-CHT and gemini surfactants.

2.1.1. UV–Vis Absorption Studies

UV–vis absorption analysis is a remarkably valuable spectroscopic technique to examine the structural change of a protein and to get confirmation about the formation of protein–ligand complexes. The aromatic residues of protein (Trp, Tyr, and Phe residues) provide absorption peaks in the UV range inferable from their phenyl rings. A change in their signal affected by the added concentration of ligands gives corroboration about the formation of a ground-state complex between the protein and the ligand.

Figure 1 demonstrates that the absorbance of the α-CHT is impaired with increase in concentration of the cationics. The spectral band from 260 to 300 nm shows the alteration in the microenvironment of the chromophore.23 These results lend support to the static quenching mechanism based on the alterations observed in the absorption of fluorophore because the complex formation can only perturb its absorption spectrum with the quencher in the ground state (static quenching) rather than in the excited state (dynamic quenching).24

Figure 1.

UV–vis absorption spectra of α-CHT in the presence of Cm-E2O-Cm (m = (a) 12, (b) 14, and (c) 16) gemini surfactants (pH 7.8) at 298 K.

2.1.2. Synchronous Fluorescence Studies

This method incorporates synchronized scanning of monochromators for excitation and emission while keeping up a constant wavelength interval between them. The spectra can provide relevant data about the molecular environment in proximity of the chromophore groups and have considerable advantages, for example, spectral interpretation, sensitivity, spectral bandwidth diminishing, and alleviation of various perturbing effects.25 When the Δλ value between emission and excitation wavelengths is stabilized at 20/60 nm, the synchronous fluorescence delivers the consonant data of Tyr and Trp residues, respectively.26,27 The maximum excitation wavelength of the residues is directly related to the polarity of the microenvironment; thus, the conformation of the protein can be evaluated from the alteration of the maximum excitation wavelength.

Figure 2 demonstrates the influence of the gemini surfactants, particularly on Tyr and Trp, on the α-CHT synchronous fluorescence spectroscopy. Comparing Figure 2a–c with Figure 2d–f, the Trp residue has the stronger fluorescence quenching than Tyr residue, implying that the aforementioned residue has a significant influence to the quenching of the α-CHT intrinsic fluorescence.28 We could also ruminate that gemini surfactants are bonded closer to Trp residues than to Tyr residues. This anomaly confirms that, during the interaction with Cm-E2O-Cm gemini surfactants, the conformation of the α-CHT has changed. The outcomes are compatible with the assertion provided by the absorption spectra.

Figure 2.

Synchronous fluorescence spectra of α-CHT (2 μM) with different concentrations of Cm-E2O-Cm (m = 12, 14, and 16) at (a–c) Δλ = 20 nm for Tyr and (d–f) Δλ = 60 nm for Trp at 298 K (pH 7.8).

2.1.3. Extrinsic Fluorescence Analysis

Pyrene is a fascinating hydrophobic molecule for examining the microenvironmental variations around the fluorophores.29 We see that the micropolarity profiles delineate the dependency of the F1/F3 value on the concentration of the Cm-E2O-Cm in the nobleness of the α-CHT (as shown in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Variation of micropolarity around pyrene as a function of Cm-E2O-Cm (m = (a) 12, (b) 14, and (c) 16) gemini surfactants at 298 K (pH 7.8).

These profiles have a comparable character for all the three systems. The F1/F3 ratio for pure water is around 1.8,30 but in this case, the ratio of α-CHT is found to be 1.76 in the absence of Cm-E2O-Cm. These results demonstrate that pyrene is localized into the hydrophobic domains of α-CHT. The first increment of gemini surfactant concentration into the α-CHT solution produces considerable alterations in the micropolarity indexes of all α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm systems. This diminishing in micropolarity ratio (F1/F3) values is brought about by the extended hydrophobic condition around the pyrene (probe) bestowed by the raised surfactant concentration. This behavior has seen up to a specific segment of the concentration of the gemini surfactant. At higher concentrations of geminis, the micropolarity of α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm systems remains unaltered, as depicted by constant F1/F3 values. This region of constancy demonstrates that molecules of the probe (pyrene) are wholly trapped inside the different micellar aggregate assemblies. From the thorough exploration of F1/F3 values, it is observed that these values emulate the pattern C16-E2O-C16 > C14-E2O-C14 > C12-E2O-C12 at the higher concentration of Cm-E2O-Cm. These outcomes reveal to have the most grounded impact on the pyrene-sensitive microenvironment compared to other lower homologues resulting from the prominent character of hydrophobic interaction forces elaborated in the concerned molecular interactions.

2.1.4. FT-IR Measurements

The FT-IR spectroscopic consequences have further revealed the complex formation between the α-CHT and gemini surfactants. FT-IR spectroscopy gives knowledge about alterations in conformation of proteins. The FT-IR spectrum of a protein indicates numerous bands for amide groups, which describe various vibrations of the peptide moiety. Among all amide modes of the peptide bonds, amide I is irrefutably the most generally utilized mode. The peaks for amide I and II take place in the 1600–1700 cm–1 region (mainly C=O stretch) and 1500–1600 cm–1 region (C–N stretch coupled with N–H bending mode) independently.

The amide I band is highly sensitive than the amide II band to the alteration in the secondary conformation of the macromolecules.31,32 The FT-IR spectra are demonstrated in Figure 4 of free α-CHT and α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm complexes. The peak correlating to the amide I band has been ascertained to illustrate a shift from 1634 to 1638 cm–1 for free α-CHT to α-CHT-bound Cm-E2O-Cm gemini surfactants. It suggests that geminis interact with the C=O and C=N groups in the α-CHT polypeptides, contributing to the rearrangement in the carbonyl H-bonding network of the polypeptide.33,34 The dramatic reduction in the intensity of amide I band and changes in peak positions in the presence of gemini surfactants reveal that the difference in the secondary structure of the α-CHT is due to α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm complex formation.

Figure 4.

FT-IR spectra of α-CHT (2 μM) in the absence and presence of 0.0867 mM Cm-E2O-Cm (m = 12, 14, and 16) gemini surfactants at 298 K (pH 7.8).

2.1.5. Three-Dimensional (3-D) Fluorescence Spectroscopy

In recent decades, the application of the three-dimensional fluorescence method has become prevalent so that the contour map in the three-dimensional spectrum affords much more scientific and systematic relevant data concerning the conformational and structural modifications of proteins.35 The conformational and microenvironmental alterations of the α-CHT have been evaluated in the absence and presence of the cationic geminis by attributing their spectral characteristics. Figure 5a–d illustrates the three-dimensional emission spectra and the equivalent contour maps (providing a bird’s eye view of the fluorescence spectra) of α-CHT in the absence and presence of the concerned surfactants.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional (3-D) fluorescence spectra of (a) α-CHT (2 μM) in the absence and presence of 2.459 μM Cm-E2O-Cm (m = (b) 12, (c) 14, and (d) 16) gemini surfactants and (e) bar diagram at 298 K (pH 7.8).

Among the four peaks, peak 1 relates to the first-order Rayleigh scattering, and peak 4 associates to the second-order Rayleigh scattering.36 Peak 2 (λex = 280 nm, λem = 340 nm) indicates the spectral behavior of Trp and Tyr, predominantly attributed to π–π* transitions of aromatic residues in the α-CHT, whereas peak 3 (λex = 225 nm, λem = 340 nm) depicts the spectral properties of a polypeptide backbone structure C=O (owing to n−π* transitions). Changes in peaks 2 and 3 demonstrate protein conformational alterations in the presence of a ligand. Figure 5 and Table 1 demonstrate that the fluorescence intensities of peaks 2 and 3 of the 3-D spectra of α-CHT get altered with the addition of gemini surfactants; this ascertains the conformational alterations in the polypeptide backbone and microenvironment also around the Tyr and Trp residues due to the binding of surfactants to α-CHT.37

Table 1. Three-Dimensional Intrinsic Fluorescence Data for 2 μM α-CHT in the Absence and Presence of 2.459 μM Cm-E2O-Cm at 298 K (pH 7.8).

| system | peak 2 (ex/em) (nm/nm) | peak 2 intensity | peak 3 (ex/em) (nm/nm) | peak 3 intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-CHT | 225/340 | 221 | 280/340 | 380 |

| α-CHT + C12-E2O-C12 | 225/341 | 213 | 280/341 | 241 |

| α-CHT + C14-E2O-C14 | 225/342 | 201 | 280/342 | 359 |

| α-CHT + C16-E2O-C16 | 225/343 | 191 | 280/343 | 350 |

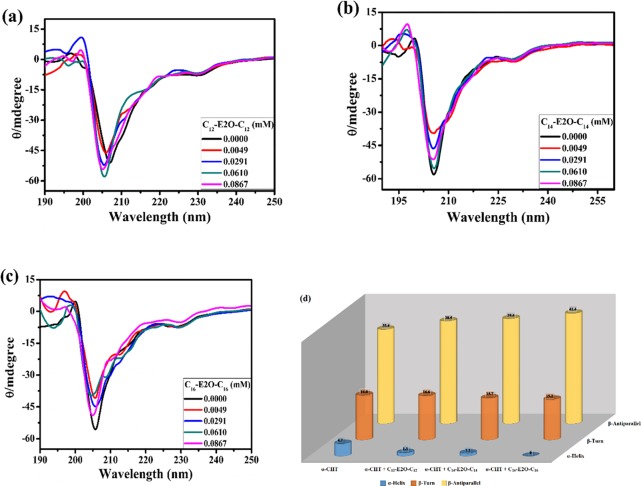

2.1.6. CD Spectral Studies

CD spectroscopy is among the utmost frequently employed methods for identifying the secondary conformation variations of proteins when combining with ligands, allowing the visualization of conformational changes in the 3-D structure of the protein.38 The assessment of far-UV CD spectra (190–240 nm) has been utilized to predict the content of various secondary conformation elements in proteins. Gorbunoff and Ettinger determined the CD spectrum of the α-CHT in 1971.39 Presently, CD spectral analysis has been performed at various concentrations of geminis to investigate the alteration in the α-CHT conformation. The CD spectrum of the α-CHT (Figure 6) shows only one negative band at around 202–205 nm and no positive band.40 The CD spectra of the α-CHT are due to the amide chromophore; the secondary structure as evaluated by CD counts amide–amide interactions, a slightly distinct number from counting residues in X-ray diffraction structures. This amide chromophore usually starts absorbing far into the UV region with the first band at around 220 nm. The α-CHT that is the kind of all β-proteins depicted by a CD spectrum is analogous to that of a random coil conformation.41 Crystal structure information of the α-CHT demonstrates that its antiparallel pleated sheets are either highly distorted or form quite short irregular strands. This anomaly may affect the negative CD band to move toward 200 nm from the optimal β-sheet position (210–220 nm).42

Figure 6.

CD spectra of α-CHT (40 μM) in the absence and presence of Cm-E2O-Cm (m = (a) 12, (b) 14, and (c) 16) gemini surfactants and (d) bar diagram at 298 K (pH 7.8).

The segment contents of various secondary conformations of the α-CHT without and with gemini surfactants have been determined to promote the BeStSel software, which is accessible at http://bestsel.elte.hu,43 and then complete fraction variations are listed in Table 2. With the addition of Cm-E2O-Cm gemini surfactants, we see a diminishing pattern of the α-helix content and rising in the β-antiparallel sheet. The results indicate that the geminis could change the secondary conformation and unfold the protein skeleton. The conformational alterations here imply the enhanced reveal of some hydrophobic localities that were previously submerged and surfactant combination with the amino acid residues of the main polypeptide chain of the α-CHT and draining of their hydrogen bonding networks.28 These results are compatible with the above outcomes of the synchronous fluorescence.

Table 2. Secondary Structure Estimation of α-CHT as a Function of [Cm-E2O-Cm] from CD Data Using BeStSel Software.

| system | α-helix | β-antiparallel | β-turn |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-CHT | 4.7 | 35.4 | 16.8 |

| α-CHT + C12-E2O-C12 | 1.3 | 38.5 | 16.6 |

| α-CHT + C14-E2O-C14 | 1.1 | 39.4 | 15.7 |

| α-CHT + C16-E2O-C16 | 0 | 41.4 | 15.2 |

2.1.7. Resonance Rayleigh Scattering (RRS) Studies

The RRS spectral technique is yet another analytical method that is recognized for its high sensitivity and effortlessness. RRS is employed to analyze the biological macromolecule interactions and molecular identification. It is highly sensitive to the interactions between the macromolecule and the ligand realized by the weak binding forces, including hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic attraction, and hydrogen bonding.44,45 The RRS spectra of the α-CHT with and without the cationics are inscribed by synchronous scanning with Δλ = 0 nm in the wavelength range of 280–800 nm. Figure S1 (Supporting Information) demonstrates that the weak RRS intensities of the α-CHT unexpectedly increase after adding the geminis; this reveals protein–surfactant interaction. The observed increase in intensity is due to the larger size of the α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm complex.

All of the above studies (UV–vis, FT-IR, CD, extrinsic, SFS, three-dimensional, and RRS fluorescence) have provided good evidence for the conformational changes of the α-CHT due to the α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm complex formation, and we will probe more of the interaction mechanism.

2.2. Investigations on the Interaction Mechanism

We have used the fluorescence spectra to investigate the interaction mode, binding parameters, and feasibility of mechanism for the interaction between the α-CHT and the Cm-E2O-Cm gemini surfactants. Furthermore, molecular docking summarizes the binding site and hydrogen bonds, and DFT analysis investigates the energy gap values (ΔE) of the HOMO–LUMO molecular orbitals of the donor–acceptor ligands.

2.2.1. Effect of Concentration of Gemini Surfactants on Fluorescence Quenching

Intrinsic fluorescence is delicate to microenvironmental changes of proteins; consequently, it is usually utilized to analyze the dynamics, conformation, and intermolecular interactions between proteins/macromolecules and ligands.46 Proteins generally have fluorescence due to the aromatic amino acid residues such as Phe, Tyr, and Trp. Fluorescence of the Phe residue is neglected in most cases because it has a meager quantum yield,47 and therefore, only Tyr and Trp contribute to the fluorescence emission. However, the intrinsic fluorescence of the α-CHT is almost wholly contributed by Trp residues (at 295 nm excitation wavelength)48 due to the quantum yield and environmental sensitivity of Trp being higher than Tyr.49 Moreover, Trp acts as a suitable probe due to the presence of the indole ring, which is favorably sensitive toward its microenvironment. Figure 7 demonstrates the emission spectra of the α-CHT with and without Cm-E2O-Cm geminis.

Figure 7.

Fluorescence emission spectra of α-CHT in the presence of Cm-E2O-Cm (m = (a) 12, (b) 14, and (c) 16) gemini surfactants at 298 K and pH 7.8.

It should be noted that the absorbances of the aforementioned cationics (in the used concentration) at the excitation and emission wavelengths of the α-CHT are much lower, and accordingly, correction factors for the inner filter are close to 1. Consequently, for the inner-filter effect in the quenching process, we have utilized eq 1 to correct the fluorescence intensity of the α-CHT.50

| 1 |

where Fcorr and Fobs are the corrected fluorescence intensity and observed intensity, respectively, and Aem and Aex are the respective absorbance values of the cationics at emission and excitation wavelengths of the α-CHT.

2.2.2. Mode of Fluorescence Quenching

Some procedures can provide confidential information to the reduction in the fluorescence intensity, that is, quenching. These procedures take place during the excited state or may be due to the interaction between the protein and the ligand in the ground state. It seems to be dynamic, ensuing from collisions between the fluorophore and quencher, or static, resulting from the ground-state complex formation between the fluorophore and the quencher.51 For fluorescence quenching, molecular contact is required between the fluorophore and the quencher in each case. Utilizations of the fluorescence quenching procedure can show the availability of the fluorophores to quenchers. To illuminate the quenching mechanism of the formation of the α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm complex formation, the Stern–Volmer equation (eq 2) was utilized for the analysis of fluorescence data:

| 2 |

where F0 and F represent the respective fluorescence intensities without and with a quencher, respectively, KSV is the Stern–Volmer quenching constant, kq is the bimolecular quenching rate constant, and τ0 (∼2.96 × 10–9 s) is the average lifetime of fluorophore in the absence of a quencher.52 Other than KSV, kq additionally delineates the kind of quenching concerned with the binding procedure for dynamic quenching; the most extreme value feasible for the scattering collision quenching constant of numerous quenchers is ∼1010 M–1 s–1.51

The Stern–Volmer plots (Figure 8) show excellent linearity in the explored concentration zone, signifying that the observed quenching processes are accountable for only one type of quenching mechanism, either static or dynamic. The results (Table 3) demonstrated that the KSV values increase with chain length in the order of C16-E2O-C16 > C14-E2O-C14 > C12-E2O-C12, the cause of the enhanced hydrophobic character influenced by the higher homologues. Further, the values of kq for the geminis that are more significant than the diffusion-controlled limit (i.e., kq max ≈ 1010 M–1 s–1)51 recommend that the ground-state complexation (static quenching mechanism) was initiated by the quenching mechanism of the α-CHT in the presence of gemini surfactants rather than by dynamic collision (dynamic quenching mechanism).

Figure 8.

Stern–Volmer plots for the binding of α-CHT with Cm-E2O-Cm (m = 12, 14, and 16) gemini surfactants at 298 K (pH 7.8).

Table 3. Binding Parameters of Interaction of α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm Systems at 298 K (pH 7.8).

| gemini surfactant | KSV (M–1) × 103 | kq (M–1 S–1) × 1012 | R2 | Kb (M–1) × 103 | n | R′2 | –ΔGb0 (kJ mol–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C12-E2O-C12 | 3.6 | 1.22 | 0.99 | 1.07 | 0.62 | 0.99 | 17.29 |

| C14-E2O-C14 | 3.81 | 1.29 | 0.99 | 1.46 | 0.66 | 0.99 | 18.06 |

| C16-E2O-C16 | 4.17 | 1.41 | 0.99 | 2.16 | 0.71 | 0.99 | 19.03 |

2.2.3. Analysis of Binding Parameters and Feasibility of the Interaction

To measure the binding stabilities of the α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm complexes, the modified Stern–Volmer equation (eq 3) was utilized53 to evaluate the binding constants (Kb) and binding sites (n), which supports the knowledge of what extent a micellar medium can perform as a suitable carrier.

| 3 |

Figure 9 demonstrates that the double-logarithmic plots log[(F0 – F)/F] versus log[Cm-E2O-Cm] (modern Stern–Volmer plot) yield a straight line in every case, whose slope is n. The values of Kb, n, and R′2 (adjusted coefficients of determination) are indexed in Table 3. For α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm complex formation, the number of binding sites is approximately equivalent to 1, suggesting the availability of a single binding site for the gemini surfactants in the α-CHT. The binding constant (Kb) results in the order of C16-E2O-C16 > C14-E2O-C14 > C12-E2O-C12, which demonstrates that C16-E2O-C16 has the highest binding strength, whereas C12-E2O-C12 holds the least effective binding affinity. This pattern is comparable to that of KSV, elucidating that hydrophobicity acts an important function in the formation of the α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm complex.

Figure 9.

Plots of log(F0 – F)/F versus log[Cm-E2O-Cm] for quenching of α-CHT by Cm-E2O-Cm (m = 12, 14, and 16) gemini surfactants; [α-CHT] = 2 μM; [Cm-E2O-Cm] = 0.0049–0.0867 mM at 298 K and pH 7.8.

Moreover, to check the feasibility of the interactions between α-CHT and gemini surfactants, the Gibbs free energy values (evaluating by using the equation ΔGb0 = – 2.303RT log Kb) demonstrate that the interactions are thermodynamically feasible. Also, the order suggests that the interaction between the α-CHT and C16-E2O-C16 is more feasible than C12-E2O-C12 and C14-E2O-C14.

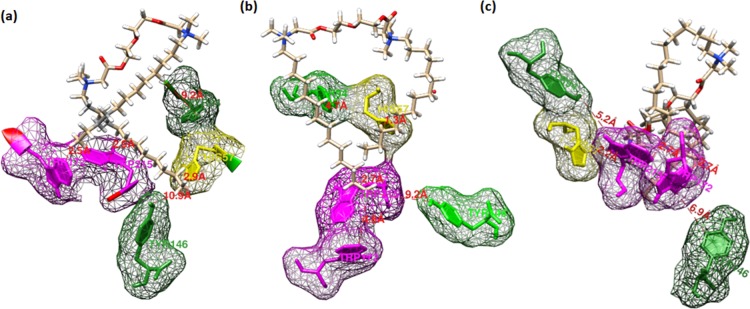

2.2.4. Molecular Docking

The molecular docking study provides an appropriate way to predict the possible binding sites. It helps sanction our experimental results and also verify the types of interactions operating in the protein–surfactant system. The binding modes of all the three geminis with α-CHT are observed to be almost similarly located around aromatic residues (Trp/Tyr) (Figure 10).The free energies of binding (FEB) of −364.9, −412.3, and −448.5 kJ mol–1 were obtained for C12-E2O-C12 + α-CHT, C14-E2O-C14 + α-CHT, and C16-E2O-C16 + α-CHT, respectively. The higher value of FEB in the last case signifies a stronger interaction as compared to the other two geminis. The docking interaction energy, that is, FEB, should not be tangled with the Gibbs free energy (ΔGb0), obtained in steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy. It is applicable to the future only in feasibility considerations. In the Hex docking, it is presumed that the ligand should be rigid, which excludes the prospect of conformational entropy predominance.

Figure 10.

Docking pose of the α-CHT complexed with (a) C12-E2O-C12, (b) C14-E2O-C14, and (c) C16-E2O-C16 gemini surfactants.

In addition, the solvent has been removed prior to docking calculations, and consequently, general structural entropy impacts are additionally satisfied. It must be recalled that the Hex 6.1 estimates the energy of interaction corresponding to the classical internal energy of a system of point charges. It could be explained as the FEB values being zero or positive, which means that the protein and ligand are infinite separations and, if these are negative scores, then favor good surface contact between the protein (α-CHT) and the ligand (surfactant). The noncompatibility in FEB and ΔGb0 has also been ascribed to the exclusion of solvent in docking simulations or the X-ray structure of proteins as crystals differ from the protein acquired in the aqueous system.54 It was observed that the gemini surfactants lie at close proximity of aromatic residues with approximate distances being C12-E2O-C12 → Trp 215.C = 2.9 Å, Trp 172.G = 2.5 Å, Tyr 95.C = 9.2 Å; C14-E2O-C14 → Trp 215.C = 2.7 Å, Trp 172.G = 4.8 Å, Tyr 171.C = 4.7 Å; and C16-E2O-C16 → Trp 215.C = 2.7 Å, Trp 172.G = 2.7 Å, Tyr 171.C = 5.2 Å.55 This close congruity suggests the probability of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions.56 The first interaction generates between the surfactant headgroups and negatively charged residues on the protein surface, and the last interactions are generally between the aromatic moieties of α-CHT and gemini surfactant tails and hydrophilic interactions. Moreover, hydrogen bonds act as a major character in the binding reaction along with van der Waals interactions, which can be seen between N of His-57.G and H of the gemini surfactant tail (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Binding sites of α-CHT with (a) C12-E2O-C12, (b) C14-E2O-C14, and (c) C16-E2O-C16 gemini surfactants.

2.2.5. DFT Calculations

Electrostatic potential analysis was made for individual gemini surfactant and aromatic residues (Trp/Tyr) using B3LYP/6-31**G(d,p) basis set DFT calculations (Figure 12). MEP (electrostatic potential map) represents the electrostatic potential strength where red regions are the most electronegative areas and, on the other hand, blue regions are the most electropositive areas. In the gemini surfactants, the electronegative region was found near the chloride ion and electropositive region near cationic nitrogen. Similarly, in the case of Trp and Tyr, the electronegative region was located near the carboxylate group and electropositive region near the aromatic residue. This suggests that the possible interaction is between cationic nitrogen of Cm-E2O-Cm and aromatic residue of Trp/Tyr and might also be in between the chloride ion of Cm-E2O-Cm and the carboxylate group of Trp/Tyr.

Figure 12.

Electrostatic potential map representing the electrostatic potential strength of (a) gemini surfactant (C12-E2O-C12) and (b) Trp and (c) Tyr residues of α-CHT.

By obtaining the optimized structure and HOMO → LUMO, HOMO-1, and LUMO+1 for Cm-E2O-Cm and aromatic residues (Trp/Tyr) of α-CHT, it was observed that the LUMO energy of Trp and Tyr molecules is very high due to the electron-withdrawing carboxylate group (Figure 13). The electronic cloud and LUMO energy of gemini surfactants and HOMO of Trp and Tyr residues are in agreement with MEP as the electrostatic interactions are also applicable between the cationic nitrogen portion of gemini surfactants and the aromatic residue of Trp/Tyr.57 Furthermore, on cautious perception of energy gap values of the concerned molecular orbitals, it is obvious that the concerned molecular orbitals have lower energy gap (ΔE) values, recommending significant interactions between the frontier molecular orbitals (FMO);58 this perception is in incongruity with the postulate of FMO theory. According to FMO theory, interactions are conceivable only when the energy gap values are not extremely high between the molecular frontier orbitals. In other words, lesser ΔE values are the indications of electronic interactions among the FMOs. From the FMO diagram of Cm-E2O-Cm and aromatic residues (Figure 13), it has been observed that the HOMO–LUMO separation between C16-E2O-C16 and aromatic residues is smaller as compared to C12-E2O-C12 and C14-E2O-C14, which makes C16-E2O-C16 a more favorable binder followed by C14-E2O-C14 than C12-E2O-C12. On the other hand, the relatively lower energy unoccupied orbital of C16-E2O-C16 and the relatively high energy filled orbital of aromatic residues reveal that the most favorable interaction is between the cationic nitrogen portion of Cm-E2O-Cm and the aromatic residue of Trp/Tyr.

Figure 13.

Optimized HOMO and LUMO configurations/energy gaps of the gemini surfactants and Trp and Tyr residues obtained via DFT calculations.

3. Conclusions

The binding study of surfactant with protein has enormous significance in pharmacy, pharmaceuticals, industry, drug delivery, and biotechnology. In this paper, the interaction of serine protease α-CHT with oxy-diester-functionalized Cm-E2O-Cm gemini surfactants was studied by spectroscopic methods including fluorescence, CD, FT-IR and UV–vis spectroscopy, in addition to molecular docking and DFT. Intrinsic fluorescence was employed to evaluate the quenching constant (KSV) whose values are 3.6 × 103, 3.81 × 103, and 4.17 × 103 M–1 for C12-E2O-C12, C14-E2O-C14, and C16-E2O-C16, respectively. The spectroscopic results acquired on the interactions of α-CHT with gemini surfactants revealed that Cm-E2O-Cm interacted strongly with α-CHT. The binding constants (Kb) of three surfactants (C12-E2O-C12, C14-E2O-C14, and C16-E2O-C16) were calculated (1.07 × 103, 1.46 × 103, and 2.16 × 103 M–1, respectively), and spontaneity was observed as shown by negative values of ΔGb0. The results of other spectroscopic techniques (namely, pyrene, synchronous, RRS, 3-D, UV–vis, FT-IR, and CD spectroscopy) stipulate the changes in the microenvironment and secondary structure of the α-CHT upon binding with Cm-E2O-Cm gemini surfactants. Molecular docking and DFT results have confirmed the involvement of hydrophobic/hydrophilic forces (hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions) and the binding of geminis in the vicinity of hydrophobic residues (Trp/Tyr) of the α-CHT.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

α-Chymotrypsin (type II, lyophilized powder) from bovine pancreas-type, essentially salt-free powder (molecular weight: 25 kDa) and pyrene (98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) and Acros Organics (Belgium), respectively. Sodium monobasic phosphate (98%) and sodium dibasic phosphate (99%) were purchased from Merck (USA). The dimeric gemini surfactants 2,2′-[(oxybis(ethane-1,2-diyl))bis(oxy)]bis(N-alkyl-N,N-dimethyl-2-oxoethanaminium dichlorides (Cm-E2O-Cm) used in this study were synthesized by the procedure described in the literature.21 The chemical structures and CMC values (reported) of Cm-E2O-Cm gemini surfactants are afforded respectively in Scheme 1a–c and Table S1 (Supporting Information).

4.2. Preparation of Stock Solutions

One milligram of α-CHT (25 kDa) was dissolved in 1 mL of 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) and kept for 24 h with incidental mixing to ensure the formation of a homogeneous solution at 298 K. The α-CHT concentration was evaluated spectrophotometrically using the molar extinction coefficient (ε) of 50,000 M–1 cm–1 at 280 nm. The stock solutions of the gemini surfactants of 1 mM were also prepared in the same buffer. A SYSTRONICS Digital pH Meter (model MK VI, India) was used for pH measurements. All experiments were performed in phosphate buffer at room temperature (298 K).

4.3. UV–Vis Absorption Spectroscopy

UV–vis absorption spectra results evaluated on a PerkinElmer Lambda 25 UV–vis spectrophotometer outfitted with a 1.0 cm quartz cell at 298 K were recorded (scan rate, 960 nm/min; scan range, 200–700 nm). Solutions of requisite concentration were prepared by adding aliquots of surfactant solutions to the native α-CHT solution.

4.4. Fluorescence Measurements

The fluorescence spectra were collected with a 1 cm path length cell at 298 K utilizing a Hitachi Model F-2700 spectrophotometer (Japan) outfitted with a PC.

For intrinsic emission fluorescence, the parameters were fixed as a excitation wavelength of 295, an emission wavelength range of 310–450 nm, excitation and emission slit widths of 5 nm, a scan rate of 1500 nm/min, and a photomultiplier tube (PMT) voltage of 400 V, maintaining the concentration of α-CHT constant at 2 μM and surfactant concentrations ranging from 0.004975 to 0.090909 mM.

The synchronous fluorescence spectra (SFS) were collected in the synchronous scan mode with offset values of 20 and 60 nm (Δλ = λem – λex = 20 or 60 nm) among excitation and emission monochromators to get specific characteristic information on Tyr and Trp residues, respectively. The widths of excitation and emission slits were set at 5 nm each, while the scan rate was 1500 nm/min.

For the extrinsic fluorescence, pyrene (3 μM) was excited at 336 nm, and emission was observed in the range of 350–450 nm. The emission and excitation slit widths were fixed at 2.5 nm, each with the scan speed 300 nm/min.

The three-dimensional fluorescence (3-D) spectra were recorded in the range of 220–600 nm, setting the emission and excitation slit widths at 5 nm, each with a 3000 nm/min scan rate.

The resonance Rayleigh scattering (RRS) spectra were recorded for the α-CHT–Cm-E2O-Cm systems through the wavelength range of 280–700 nm, employing synchronous scanning at Δλ = 0 (i.e., λem = λex).

4.5. FT-IR Measurements

The FT-IR spectra were measured utilizing the PerkinElmer Lambda spectrophotometer in the range of 400–4000 cm–1. Baseline correction was obliged utilizing the phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) as a blank before the measurements.

4.6. Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy

The far-UV CD spectra of α-CHT and gemini surfactants were recorded by utilizing a JASCO-J815 CD spectropolarimeter furnished with a PC and a quartz cuvette with 10 mm path length. The far-UV CD spectra were recorded between 190 and 250 nm and with a 40 μM α-CHT solution. The spectra were accumulated at the scan rate of 100 nm min–1 with the response time of 1 s and the bandwidth of 1 nm. The spectropolarimeter was cleansed adequately with inert N2 gas, and calibration with d-10-camphorsulfonic acid was performed before and during the measurements. After the proper baseline correction, the acquired CD spectra are an average of two successive scans. During the measurements, the temperature was constant at 298 K.

4.7. Molecular Docking

To study the behavior of molecular interaction between the ligand (gemini surfactant) and the protein (α-CHT), Hex 6.1 software was used59 with shape + DARS + electrostatic correlation, and Grid: 118X118X118. PDB file of α-CHT with code 4CHA was downloaded from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org), while mol files of Cm-E2O-Cm gemini surfactants were developed by using ChemDraw Ultra 12.0 and converted into PDB format by using Chimera. Visualization of docking pose was obtained using Chimera software (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera). The overall docking experiment was run on a processor (Intel Core i5-4200U CPU @ 1.60 GHz, 2.10 GHz, 2.30 GHz, 64-bit).

4.8. DFT Studies

All the density functional theory calculations to study the interaction between gemini surfactant and hydrophobic residues (Trp/Tyr) of α-CHT were obtained through B3LYP/6-31**G(d,p) basis set (Becke’s three-parameter hybrid exchange function with Pople basic set) using the Gaussian 09 program.60 The electrostatic potential map (MEP) of optimized structures, HOMO and LUMO, were also obtained. The visualization of investigated structures was done using ChemCraft1.5 software.61

Acknowledgments

The authors are highly thankful to the Chairman, Department of Chemistry, AMU, for providing the necessary facilities to carry out this research work. The PURSE and FIST grants from DST and SAP DRS-II grant from UGC are acknowledged.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b04142.

Figure of RRS fluorescence spectra and table containing CMC values of cationic Cm-E2O-Cm gemini surfactants (PDF)

Author Present Address

‡ Present address: Department of Chemistry, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch, Ethiopia.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Mahmoudi M.; Lynch I.; Ejtehadi M. R.; Monopoli M. P.; Bombelli F. B.; Laurent S. Protein–Nanoparticle Interactions: Opportunities and Challenges. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5610–5637. 10.1021/cr100440g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch I.; Dawson K. A. Protein-Nanoparticle Interactions. Nano Today 2008, 3, 40–47. 10.1016/S1748-0132(08)70014-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akram M.; Anwar S.; Kabir-ud-Din Biophysical Investigation of Promethazine Hydrochloride Binding with Micelles of Biocompatible Gemini Surfactants: Combination of Spectroscopic and Electrochemical Analysis. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2019, 215, 249–259. 10.1016/j.saa.2019.02.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon B. S. Surfactants: Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Aspects. J. Pharm. Technol. Res. Manage. 2013, 1, 43–68. 10.15415/jptrm.2013.11004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li P.; Nielsen H. M.; Fano M.; Müllertz A. Preparation and Characterization of Insulin–Surfactant Complexes for Loading into Lipid-Based Drug Delivery Systems. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 102, 2689–2698. 10.1002/jps.23640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y.; Wei W.; Zhang J.; Zhang S. Interaction Process between Ionic Surfactant and Protein Probed by Series Piezoelectric Quartz Crystal Technique. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 2002, 52, 19–29. 10.1016/S0165-022X(02)00026-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W.; Ding L.; Cao J.; Liu L.; Wei Y.; Fang Y. Protein Binding-Induced Surfactant Aggregation Variation: A New Strategy of Developing Fluorescent Aqueous Sensor for Proteins. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 4728–4736. 10.1021/am508421n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat I. A.; Roy B.; Kabir-ud-Din Micelles of Cleavable Gemini Surfactant Induce Fluorescence Switching in Novel Probe: Industrial Insight. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 77, 60–64. 10.1016/j.jiec.2019.04.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yesilyurt V.; Ramireddy R.; Thayumanavan S. Photoregulated Release of Noncovalent Guests from Dendritic Amphiphilic Nanocontainers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3038–3042. 10.1002/anie.201006193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings N. D.; Barrett A. J. MEROPS: The Peptidase Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 325–331. 10.1093/nar/27.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Venkatesu P. Overview of the Stability of α-Chymotrypsin in Different Solvent Media. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 4283–4307. 10.1021/cr2003773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum B. J.; Margolies M. R.; Doku H. C.; Murnane T. W. The Effect of α-Chymotrypsin on Wound Healing in Hamsters. Oral Surg., Oral Med., Oral Pathol. 1972, 33, 484–489. 10.1016/0030-4220(72)90479-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen M. J.; Kunjappu J. T.. Surfactants And Interfacial Phenomena; 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Wang X.; Wang Y. Comparative Studies on Interactions of Bovine Serum Albumin with Cationic Gemini and Single-Chain Surfactants. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 8499–8505. 10.1021/jp060532n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D.; Xu G.; Sun Y.; Zhang H.; Mao H.; Feng Y. Interaction between Proteins and Cationic Gemini Surfactant. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 708–712. 10.1021/bm061033v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gull N.; Sen P.; Khan R. H.; Kabir-ud-Din Spectroscopic Studies on the Comparative Interaction of Cationic Single-Chain and Gemini Surfactants with Human Serum Albumin. J. Biochem. 2008, 145, 67–77. 10.1093/jb/mvn141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gull N.; Sen P.; Khan R. H.; Kabir-ud-Din Interaction of Bovine (BSA), Rabbit (RSA), and Porcine (PSA) Serum Albumins with Cationic Single-Chain/Gemini Surfactants: A Comparative Study. Langmuir 2009, 25, 11686–11691. 10.1021/la901639h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funasaki N.; Ohigashi M.; Hada S.; Neya S. Surface Tensiometric Study of Multiple Complexation and Hemolysis by Mixed Surfactants and Cyclodextrins. Langmuir 2000, 16, 383–388. 10.1021/la9816813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stjerndahl M.; van Ginkel C. G.; Holmberg K. Hydrolysis and Biodegradation Studies of Surface-Active Esters. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2003, 6, 319–324. 10.1007/s11743-003-0276-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani-Bagha A. R.; Holmberg K. Cationic Ester-Containing Gemini Surfactants: Physical–Chemical Properties. Langmuir 2010, 26, 9276–9282. 10.1021/la1001336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akram M.; Anwar S.; Ansari F.; Bhat I. A.; Kabir-ud-Din Bio-Physicochemical Analysis of Ethylene Oxide-Linked Diester-Functionalized Green Cationic Gemini Surfactants. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 21697–21705. 10.1039/C5RA28129F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akram M.; Bhat I. A.; Anwar S.; Kabir-ud-Din Biophysical Analysis of Novel Oxy-Diester Hybrid Cationic Gemini Surfactants (C m -E2O-C m ) with Xanthine Oxidase (XO). Process Biochem. 2016, 51, 1212–1221. 10.1016/j.procbio.2016.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X.; Liu R.; Qin P.; Wang L.; Zhao X. Spectroscopic Studies on the Interaction of Acid Yellow With Bovine Serum Albumin. J. Lumin. 2010, 130, 611–617. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2009.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.; Liu Q.; Wen Y. Spectroscopic studies on the interaction between nicotinamide and bovine serum albumin. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2008, 71, 984–988. 10.1016/j.saa.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.-J.; Liu Y.; Pi Z.-B.; Qu S.-S. Interaction of Cromolyn Sodium with Human Serum Albumin: A Fluorescence Quenching Study. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 6609–6614. 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G.; Zhao N.; Wang L. Probing the Binding of Vitexin to Human Serum Albumin by Multispectroscopic Techniques. J. Lumin. 2011, 131, 880–887. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2010.12.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.; Wu X.; Gu X.; Zhou L.; Song K.; Wei S.; Feng Y.; Shen J. Spectroscopic Studies on the Interaction of Hypocrellin A and Hemoglobin. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2009, 72, 151–155. 10.1016/j.saa.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N.; Ye L.; Yan F.; Xu R. Spectroscopic Studies on the Interaction of Azelnidipine with Bovine Serum Albumin. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 351, 55–60. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard E. D.; Turro N. J.; Kuo P. L.; Ananthapadmanabhan K. P. Fluorescence Probes for Critical Micelle Concentration Determination. Langmuir 1985, 1, 352–355. 10.1021/la00063a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilescu M.; Angelescu D.; Almgren M.; Valstar A. Interactions of Globular Proteins with Surfactants Studied with Fluorescence Probe Methods. Langmuir 1999, 15, 2635–2643. 10.1021/la981424y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Surewicz W. K.; Mantsch H. H.; Chapman D. Determination of Protein Secondary Structure by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy: A Critical Assessment. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 389–394. 10.1021/bi00053a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W.; Li Y.; Xue C.; Hu Z.; Chen X.; Sheng F. Effect of Chinese Medicine Alpinetin on the Structure of Human Serum Albumin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 1837–1845. 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y.; Liu J.; Liu R.; Dong Q.; Fan J. Binding of Helicid to Human Serum Albumin: A Hybrid Spectroscopic Approach and Conformational Study. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2014, 124, 46–51. 10.1016/j.saa.2013.12.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikirić M.; Primožič I.; Talmon Y.; Filipović-Vinceković N. Effect of the Spacer Length on the Association and Adsorption Behavior of Dissymmetric Gemini Surfactants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 281, 473–481. 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.08.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Jiang X.; Zhou L.; Cheng Z.; Yin W.; Duan M.; Liu P.; Jiang X. Interaction of NAEn-s-n Gemini Surfactants with Bovine Serum Albumin: A Structure–Activity Probe. J. Lumin. 2013, 134, 138–147. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2012.08.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaroog M. S.; Tayyab S. Formation of Molten Globule-like State during Acid Denaturation of Aspergillus Niger Glucoamylase. Process Biochem. 2012, 47, 775–784. 10.1016/j.procbio.2012.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meti M. D.; Nandibewoor S. T.; Joshi S. D.; More U. A.; Chimatadar S. A. Multi-Spectroscopic Investigation of the Binding Interaction of Fosfomycin with Bovine Serum Albumin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2015, 5, 249–255. 10.1016/j.jpha.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragh-Hansen U. Molecular Aspects of Ligand Binding to Serum Albumin. Pharmacol. Rev. 1981, 33, 17–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbunoff M. J.; Ettinger P. Tyrosine Environment Differences in the Chymotrypsins. Biochemistry 1971, 10, 250–257. 10.1021/bi00778a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon L. M.; Kotormán M.; Garab G.; Laczó I. Structure and Activity of α-Chymotrypsin and Trypsin in Aqueous Organic Media. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 280, 1367–1371. 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessey J. P. Jr.; Johnson W. C. Jr. Information Content in the Circular Dichroism of Proteins. Biochemistry 1981, 20, 1085–1094. 10.1021/bi00508a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manavalan P.; Johnson W. C. Jr. Sensitivity of Circular Dichroism to Protein Tertiary Structure Class. Nature 1983, 305, 831–832. 10.1038/305831a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Micsonai A.; Wien F.; Kernya L.; Lee Y.-H.; Goto Y.; Réfrégiers M.; Kardos J. Accurate Secondary Structure Prediction and Fold Recognition for Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, E3095–E3103. 10.1073/pnas.1500851112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Li Y. Study on Resonance Rayleigh Scattering Spectra of Mercaptopurine-Cu(II)-Nucleic Acid System. Am. J. Anal. Chem. 2012, 03, 181–187. 10.4236/ajac.2012.33026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madrakian T.; Bagheri H.; Afkhami A.; Soleimani M. Spectroscopic and Molecular Docking Techniques Study of the Interaction between Oxymetholone and Human Serum Albumin. J. Lumin. 2014, 155, 218–225. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2014.06.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat I. A.; Bhat W. F.; Akram M.; Kabir-ud-Din Interaction of a Novel Twin-Tailed Oxy-Diester Functionalized Surfactant with Lysozyme: Spectroscopic and Computational Perspective. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 1006–1011. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.11.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y.; Liu M.; Chen S.; Chen X.; Wang J. New Insight into Molecular Interactions of Imidazolium Ionic Liquids with Bovine Serum Albumin. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 12306–12314. 10.1021/jp2071925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Diego T.; Lozano P.; Gmouh S.; Vaultier M.; Iborra J. L. Fluorescence and CD Spectroscopic Analysis of the ?-Chymotrypsin Stabilization by the Ionic Liquid, 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis[(Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl]Amide. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004, 88, 916–924. 10.1002/bit.20330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attri P.; Jha I.; Choi E. H.; Venkatesu P. Variation in the Structural Changes of Myoglobin in the Presence of Several Protic Ionic Liquid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 69, 114–123. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anbazhagan V.; Renganathan R. Study on the Binding of 2,3-Diazabicyclo[2.2.2]Oct-2-Ene with Bovine Serum Albumin by Fluorescence Spectroscopy. J. Lumin 2008, 128, 1454–1458. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2008.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz J. R.Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy; 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Liu R. The interaction of α-chymotrypsin with one persistent organic pollutant (dicofol): Spectroscope and molecular modeling identification. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 3298–3305. 10.1016/j.fct.2012.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min J.; Meng-Xia X.; Dong Z.; Yuan L.; Xiao-Yu L.; Xing C. Spectroscopic Studies on the Interaction of Cinnamic Acid and Its Hydroxyl Derivatives with Human Serum Albumin. J. Mol. Struct. 2004, 692, 71–80. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2004.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akram M.; Bhat I. A.; Kabir-ud-Din New Insights into Binding Interaction of Novel Ester-Functionalized m-E2-m Gemini Surfactants with Lysozyme: A Detailed Multidimensional Study. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 102780–102794. 10.1039/C5RA20576J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R.; Mir M. U. H.; Maurya J. K.; Singh U. K.; Maurya N.; Parray M. u. d.; Khan A. B.; Ali A. Spectroscopic and Molecular Modelling Analysis of the Interaction between Ethane-1,2-Diyl Bis( N , N -Dimethyl- N -Hexadecylammoniumacetoxy)Dichloride and Bovine Serum Albumin. Luminescence 2015, 30, 1233–1241. 10.1002/bio.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zana R.; Talmon Y. Dependence of Aggregate Morphology on Structure of Dimeric Surfactants. Nature 1993, 362, 228–230. 10.1038/362228a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.; Dai C.; Fang S.; Li H.; Wu Y.; Sun X.; Zhao M. The Effect of Hydroxyl on the Solution Behavior of a Quaternary Ammonium Gemini Surfactant. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 16047–16056. 10.1039/C7CP00131B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyab M. A.; Osman M. M.; Elkholy A. E.; Heakal F. E.-T. Green Approach towards Corrosion Inhibition of Carbon Steel in Produced Oilfield Water Using Lemongrass Extract. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 45241–45251. 10.1039/C7RA07979F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie D. W.; Venkatraman V. Ultra-Fast FFT Protein Docking on Graphics Processors. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2398–2405. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.Gaussian 09; Revision E.01, Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT. 2009.

- Zhurko G. A.; Zhurko D. A.. Chemcraft - Graphical Program for Visualization of Quantum Chemistry Computations, trial version; Ivanovo, Russia, Academic Version 1.5. 2004.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.