Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Incomplete circle of Willis (CoW) configuration is an important risk factor for cerebrovascular pathology, namely aneurysm formation and ischemic stroke. This study was performed to characterize CoW variation using digital subtraction angiography and to identify demographic and physiologic features that may influence the risk of having an incomplete CoW configuration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A retrospective review of 274 patients who underwent cerebral angiography by a single surgeon for any indication was conducted. Each CoW branch was graded as normal, hypoplastic, or aplastic. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were conducted to assess the impact of age, gender, race, and certain comorbidities on CoW configuration.

RESULTS:

A complete CoW was identified in 37.23% of patients. In univariate analysis, patients <40 years old were more likely to have a complete CoW (odds ratio [OR]: 4.973, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.610–9.476, P < 0.001) as were patients <70 years old (OR: 2.849, 95% CI: 1.131–7.194, P < 0.05). Univariate analysis on demographic factors and comorbidities revealed CoW completeness to decrease with hypertension (OR: 0.575, 95% CI: 0.347–0.951, P = 0.031) and diabetes mellitus (OR: 0.368, 95% CI: 0.180–0.754, P = 0.006). Multivariable logistic regression analysis used to assess the impact of age on CoW completeness showed age to be an independent predictor of complete CoW, with an inverse correlation between increasing age and CoW completeness (OR: 0.955, 95% CI: 0.937–0.973, P < 0.001) after controlling for potential confounders including hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

CONCLUSIONS:

CoW configuration shows considerable variation with age; however, further investigation is required to elucidate the full impact of other demographic and vascular risk factors on CoW anatomy.

Keywords: Age, cerebral arteries, circle of Willis, demographic, digital subtraction angiography

Introduction

The Circle of Willis (CoW), the epicenter of cerebral blood flow, provides crucial collateral circulation through its seven major branches. Given its importance in neurovascular physiology, even slight variations to the normal anatomy of this eminent structure can have clinical repercussions. Experimental and computational models suggest that increased flow through an abnormal configuration of patent branches increases wall sheer stress leading to aneurysmal formation.[1,2,3,4] Similarly, incomplete configuration increases the risk of ischemic stroke, likely due to reduced collateral circulation.[4,5]

An incomplete CoW as a risk factor for stroke and aneurysm formation continues to be a focus of research in cerebrovascular disease. In 1984, Kayembe et al.[6] found aneurysms to be more common in autopsy studies in patients with CoW anatomic variations, a finding suggested by CoW assessment with advanced imaging. Individuals with variations in the CoW are more likely to have aneurysmal recurrence after endovascular treatment[7] and may be at higher risk for aneurysmal rupture.[8,9] Variation of the first segment of the anterior cerebral artery increases the likelihood of having an anterior communicating artery aneurysm[10] and puts individuals at risk for infarct after aneurysmal rupture.[11] Acute ischemic stroke risk is similarly elevated in individuals with variant CoW configurations.[5,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] Individuals with good cerebral collateral circulation tend to have smaller infarct size at baseline and higher rates of neurological improvement following acute ischemic stroke.[19,20]

A recent work by Zaninovich et al.[21] supports the emerging theory that age and gender have a significant effect on the rates of complete CoW, which subsequently impacts these disease states. Women have a higher lifetime risk of stroke, more frequent recurrences, and higher mortality, whereas men have the risk of first stroke at a younger age.[22] Notably, stroke risk strongly correlates with age in both genders.[22] Ghods et al. showed that gender affects aneurysmal location, in which women are more likely to have multiple aneurysms, aneurysms of the internal carotid artery, and tend to present with subarachnoid hemorrhage.[23] With regard to age, middle cerebral artery aneurysms are less common with age >55 years, and women are more likely to present later in life.[23,24]

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) remains the gold standard for assessing cerebral arteries and is particularly successful in identifying hypoplastic vessels when compared to computed tomography angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA).[25,26,27] The primary objective of this study was to describe CoW completeness with respect to age, gender, and race as assessed by DSA, rather than noninvasive imaging, which tends to be less specific. To our knowledge, this is the largest patient cohort to be assessed by DSA, allowing for characterization of anatomic variations of each major vessel, including fetal posterior communicating arteries. The mechanism underlying apparent changes in CoW configuration with age has yet to be elucidated, although this is hypothesized to be secondary to a combination of factors including atherosclerosis.[28,29] As such, this study also seeks to describe the population and patient factors associated with incomplete CoW with respect to known atherosclerotic risk factors, namely blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and body mass index.[30]

Materials and Methods

Patients

The study was approved by the institutional review board with a waiver of consent, given that all data were gathered retrospectively and anonymously. From January 2016 to March 2018, 322 consecutive patients who underwent DSA for any indication by a single surgeon were included in the study. Clinical indications for DSA included ischemic stroke, cerebral aneurysm, suspected vasospasm, intracerebral hemorrhage, vessel dissection, transverse sinus stenosis, severe epistaxis, arteriovenous malformation, and dural arteriovenous fistula. Of the initial 322 patients, 48 were excluded due to (1) incomplete imaging due to either missing internal carotid artery or vertebral artery injections, (2) occlusion or severe stenosis of vasculature proximal to the CoW, or (3) patients with moderate or severe vasospasm. Patients diagnosed with Moyamoya disease were also excluded from the study.

Patient information was gathered via a retrospective review of personal health information. Demographic information was used to compile age, gender, and race. The International Classification of Diseases-9 and International Classification of Diseases-10 codes were used to describe whether patients had any of the comorbidities of interest, including Type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, prior cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic accident, and obstructive sleep apnea at the time of angiography. Body mass index was calculated using the patients' height and weight measurements. Hyperlipidemia was defined as any preangiography low-density lipoprotein value ≥100 mg/dl. Smoking status was determined by evaluating documentation obtained preangiography, with any documented previous smoking history being considered positive.

Image acquisition

DSA images were acquired via transfemoral approach with a 4 Fr or 5 Fr catheter in a fully equipped DSA unit. A catheter was advanced into the right and left internal carotid arteries and a vertebral artery. Contrast was injected manually, and images were captured at 3 frames/s. Anteroposterior and lateral images were obtained with oblique images variably obtained based on pathology identified during angiography.

Image analysis

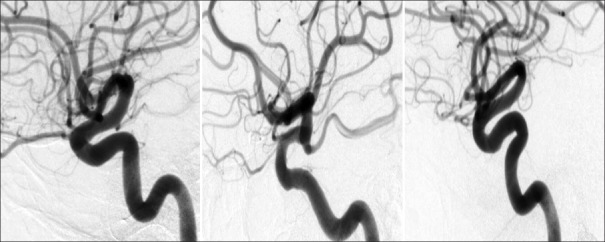

All DSA images were reviewed by three blinded reviewers. To minimize differences between prior studies on CoW configuration, the major branches of the CoW were considered to be the anterior communicating artery, the first segments of both anterior cerebral arteries, the first segments of both posterior cerebral arteries, and both posterior communicating arteries.[21,25] Each segment was graded as normal, hypoplastic, or aplastic [Figure 1]. Hypoplastic was defined as vessel size <30% of the size of the ipsilateral distal vessel. For the posterior communicating artery and the first segment of posterior cerebral artery, this was the second segment of the posterior cerebral artery, and for anterior circulation arteries, this was the second segment of the anterior cerebral artery.[25] Aplastic vessels were defined as a vessel that could not be identified on any DSA image.

Figure 1.

Original digital subtraction angiography image of posterior communicating artery variation. Examples of hypoplastic (left), normal (middle), and aplastic (right) posterior communicating artery

Statistical analysis

The incidence of each vessel segment of the CoW was tabulated for the entire cohort. The frequency of incomplete CoW was defined as any CoW with at least one aplastic vessel and was calculated for three age groups (ages <40, 40–69, and ≥70 years). The incidence of incomplete CoW was found within each demographic and comorbid disease group of interest including gender, race, diabetes mellitus, smoking status, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease or peripheral artery disease, prior cerebrovascular accident including transient ischemic accident, obstructive sleep apnea, and obesity. Univariate binary logistic and linear regression analyses were used to assess the impact of categorical and continuous dependent variables, respectively. Finally, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the potential predictors of CoW completeness with respect to age using co-variants that approached statistical significance (P < 0.20) on univariate analysis.

Results

The overall incidence of patent, hypoplastic, and aplastic vessels for each of the seven major branches of the CoW is listed in Table 1. The overall incidence of a complete CoW in the entire patient cohort was 37.23% when incomplete CoW was defined as any aplastic vessels. The incidence of a complete CoW was 8.03% when an incomplete CoW was defined as any hypoplastic or aplastic vessels. The most common variants were an aplastic left posterior communicating artery (31.75%) and a hypoplastic right posterior communicating artery (29.56%). The incidence of normal vessels in the anterior circulation was 68.25% for anterior communicating artery and 95.26% and 91.24% for the first segments of left and right anterior cerebral arteries, respectively. The left and right posterior communicating arteries were normal in 25.18% and 25.91% of cases, respectively, whereas the left and right posterior cerebral arteries were normal in caliber in 88.32% and 85.77% of cases, respectively. Hypoplastic and aplastic vessels were seen in greatest frequency in the anterior communicating artery and posterior communicating arteries. Fetal posterior communicating arteries were present in 14.60% of patients on the left and 16.79% on the right.

Table 1.

Original data on the incidence of normal, hypoplastic, aplastic, and fetal circle of Willis branches

| Normal, n (%) | Hypoplastic, n (%) | Aplastic, n (%) | Fetal, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-CommA | 187 (68.25) | 56 (20.44) | 31 (11.31) | - |

| Left A1 | 261 (95.26) | 10 (3.65) | 3 (1.09) | - |

| Right A1 | 250 (91.24) | 12 (4.38) | 12 (4.38) | - |

| Left P-CommA | 69 (25.18) | 78 (28.47) | 87 (31.75) | 40 (14.60) |

| Right P-CommA | 71 (25.91) | 81 (29.56) | 76 (27.74) | 46 (16.79) |

| Left P1 | 242 (88.32) | 11 (4.01) | 21 (7.66) | - |

| Right P1 | 235 (85.77) | 20 (7.30) | 19 (6.93) | - |

A-CommA: Anterior communicating artery, A1: First segment of anterior cerebral artery, P-CommA: Posterior communicating artery, P1: First segment of posterior cerebral artery

Patients aged <40, 40–69, and ≥70 years had a complete CoW in 67.92%, 31.75%, and 18.75%, respectively [Table 2]. On univariate analysis, patients <40 years old were more likely to have a complete CoW (odds ratio [OR]: 4.973, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.610–9.476, P < 0.001) as were patients <70 years old (OR: 2.849, 95% CI: 1.131–7.194, P < 0.05) compared to patients aged ≥70 years. Overall, increasing age correlates with total aplastic and hypoplastic vessels (β = 0.017, 95% CI: 0.011–0.024, P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Original data on the impact of age on circle of Willis completeness

| Age (years) | Patients (n) | Completion frequency (%) | Mean age (SD) | Univariate analysis for complete CoW, OR (95% CI); P | Univariate analysis for total hypoplastic and aplastic vessels, β coefficient (95% CI); P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <40 | 53 | 67.92 | 28.94 (6.08) | 4.975 (2.611-9.434); <0.001 | −0.571 (−0.833-−0.309); <0.001 |

| 40-69.99 | 189 | 31.75 | 55.77 (8.15) | 2.101 (1.244-3.546); <0.01 | 0.315 (0.087-1.848); <0.01 |

| ≥70 | 32 | 18.75 | 74.72 (4.19) | 0.351 (0.139-0.884); 0.026 | 0.211 (−0.121-0.543); 0.211 |

| Total | 274 | 37.23 | 52.79 (15.08) | 0.954 (0.937-0.972); <0.001 | 0.017 (0.011-0.024); <0.001 |

SD: Standard deviation, OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval, CoW: Circle of Willis

There was no significant difference in the frequency of CoW completeness with respect to gender or race [Table 3]. On univariate regression analysis [Table 4], both hypertension (OR: 0.575, 95% CI: 0.347–0.951, P = 0.031) and diabetes mellitus (OR: 0.368, 95% CI: 0.180–0.754, P = 0.006) correlated with decreased CoW completeness. Multivariate regression analysis showed age to be an independent predictor of complete CoW with an inverse correlation between increasing age and CoW completeness (OR: 0.955, 95% CI: 0.937–0.973, P < 0.001) when controlling for potential confounding variables including African-American race, other race, hypertension, history of cerebrovascular accident, and diabetes mellitus. Importantly, when controlling for age, diabetes mellitus and hypertension did not significantly correlate with CoW completeness status.

Table 3.

Original data on the influence of demographic factors on circle of Willis completeness

| Patients (n) | Age, mean (SD) | Completion frequency (%) | OR (95% CI); P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 175 | 51.21 (14.84) | 38.29 | 1.134 (0.679-1.894); 0.630 |

| Male | 99 | 55.59 (15.10) | 35.35 | - |

| Caucasian | 217 | 52.98 (15.42) | 36.41 | 1.165 (0.635-2.135); 0.622 |

| African-American | 55 | 52.14 (13.50) | 40.00 | 0.570 (0.295-1.098); 0.093 |

OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval, SD: Standard deviation

Table 4.

Original data on the impact of risk factors for atherosclerotic vascular disease on circle of Willis completeness

| Patients (n) | Completion frequency (%) | OR (95% CI); P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smokers | 161 | 34.78 | 0.801 (0.486-1.318); 0.382 |

| Nonsmokers | 108 | 40.74 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 42 | 30.95 | 0.614 (0.270-1.396); 0.245 |

| LDL <100 mg/dL | 64 | 42.19 | |

| Hypertension | 170 | 32.35 | 0.575 (0.347-0.951); 0.031 |

| No hypertension | 103 | 45.63 | |

| CAD or PAD | 49 | 40.82 | 1.186 (0.631-2.232); 0.597 |

| No CAD or PAD | 224 | 36.61 | |

| Prior CVA | 56 | 46.43 | 1.597 (0.881-2.890); 0.123 |

| No prior CVA | 217 | 35.02 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 53 | 20.75 | 0.368 (0.180-0.754); 0.006 |

| No diabetes mellitus | 220 | 41.36 | |

| OSA | 20 | 35.00 | 0.895 (0.335-2.326); 0.821 |

| No OSA | 253 | 37.55 | |

| BMI >30 | 106 | 36.79 | 0.986 (0.595-1.631); 0.956 |

| Normal BMI | 167 | 37.13 |

LDL: Low-density lipoprotein, CAD: Coronary artery disease, PAD: Peripheral artery disease, CVA: Cerebrovascular accident, OSA: Obstructive sleep apnea, BMI: Body mass index, OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval

Discussion

CoW completeness has varied considerably in imaging[31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] and autopsy[6,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] studies. The completeness rate in this study replicates a recent large sample study with a similar focus using CTA.[21] The functional assessment afforded by DSA allows for accurate characterization of small-diameter vessels into aplastic versus hypoplastic. This nuanced evaluation of hypoplastic vessels altered the completion frequency considerably when hypoplastic vessels were considered incomplete. The largest DSA CoW analysis, a 117-patient series conducted by Han et al.[25] previously with an analogous vascular grading scale, showed high variability in the communicating segments relative to the first segments of both the anterior and posterior cerebral arteries. This high degree of variation was replicated in this study, with the anterior and posterior communicating arteries showing considerable variation, an anomaly that has known significant clinical ramifications in cerebrovascular pathology.[10,11] To our knowledge, this is the first dedicated DSA assessment of fetal posterior circulation, which has been cited as a potential risk factor for ischemic strokes.[16] The incidence of approximately 15% overall in this study was comparable to an incidence of 11%–46% documented in a recent review.[51]

The degree of environmental and genetic contributions to CoW configuration remains unclear.[52] In a mouse model,[28] both aging and hypertension were found to reduce posterior communicating artery diameter. However, it has been demonstrated that posterior communicating artery variations occur more often within a family.[29] In this study, younger patient age was highly predictive of CoW completeness, a relationship becoming increasingly well established in literature.[21,32,37,38,39] The results of this study strengthen this association, finding age to be an independent predictor of complete CoW, even after controlling for hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

The two other demographic variables assessed (gender and race) showed no significant difference in CoW completeness. Previous studies have found a higher female preponderance;[32,34,38] however, others[39,53] have reported opposite findings, with men having a slightly higher completeness. Racial and ethnic differences in configuration have been a recent research focus, in which a Sri Lankan autopsy study[46] demonstrated that CoW configuration varied among ethnicity. MRA evaluation of CoW in Ecuadorian Mexicans,[54] Turkish,[42] and Pakistani[41] populations yielded variable completeness incidence of 65.10%, 85%, and 22.2%, respectively. Due to challenges in assessing ethnic background via the personal health information system, this study estimated differences in ethnicity using race, and thus it is possible that a more refined categorization with respect to ethnic background may show a difference and should be a consideration for similar studies in future.

Atherosclerosis follows an analogous age-based trajectory to CoW completeness frequency changes and is heavily affected by blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and body mass index.[30] One study found no relationship between cerebral small-vessel disease and CoW completeness,[55] supporting a potential hypothesis that configuration changes require continuous vascular demand on large-diameter arteries. This study showed that hypertension and diabetes mellitus were associated with an increased odds of having an incomplete CoW. However, when included in a multivariate analysis, age was found to be the primary mechanistic driver impacting CoW vessel anatomy, rather than these confounding comorbidities. Interestingly, other comorbidities analyzed which are also strongly associated with age such as hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease or peripheral artery disease, and prior cerebrovascular accident did not reach significance in the regression analysis. It is certainly possible that this study was underpowered to adequately evaluate the impact of the conditions and thus a larger review may be helpful in further establishing this relationship.

The population of patients undergoing cerebral angiography is weighed toward individuals with cerebrovascular conditions, specifically evaluation of stroke and aneurysm, which is known to decrease CoW completeness.[21,56] Unfortunately, this problem is inherent to assessments made by DSA which is an invasive test, requiring appropriate indications. Using a study population more representative of a healthy population using CTA or MRA imaging would potentially produce different results. Finally, this study is of descriptive and retrospective nature and future work should focus on prospectively following a health population over time to further solidify the effect of age on CoW configuration.

Conclusions

CoW anatomy, as assessed by DSA, shows considerable variation. Complete CoW is closely and inversely related to age. The relationship between CoW completeness and other demographic factors, such as race and gender, did not reach significance in this study. Furthermore, comorbid conditions commonly associated with atherosclerosis and cerebrovascular disease did not significantly affect CoW completeness when controlling for age. Further work is needed to elucidate the mechanism behind the age-related decline in CoW completeness and to anticipate which individuals are at risk of CoW incompleteness and its associated pathologic effects.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Fahy P, McCarthy P, Sultan S, Hynes N, Delassus P, Morris L. An experimental investigation of the hemodynamic variations due to aplastic vessels within three-dimensional phantom models of the circle of Willis. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42:123–38. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0905-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alnaes MS, Isaksen J, Mardal KA, Romner B, Morgan MK, Ingebrigtsen T. Computation of hemodynamics in the circle of Willis. Stroke. 2007;38:2500–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.482471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nam SW, Choi S, Cheong Y, Kim YH, Park HK. Evaluation of aneurysm-Associated wall shear stress related to morphological variations of circle of Willis using a microfluidic device. J Biomech. 2015;48:348–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pascalau R, Padurean VA, Bartos D, Bartos A, Szabo BA. The geometry of the circle of Willis anatomical variants as a potential cerebrovascular risk factor. Turk Neurosurg. 2019;29:151–8. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.21835-17.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoksbergen AW, Legemate DA, Csiba L, Csáti G, Síró P, Fülesdi B. Absent collateral function of the circle of Willis as risk factor for ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;16:191–8. doi: 10.1159/000071115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kayembe KN, Sasahara M, Hazama F. Cerebral aneurysms and variations in the circle of Willis. Stroke. 1984;15:846–50. doi: 10.1161/01.str.15.5.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Songsaeng D, Geibprasert S, Willinsky R, Tymianski M, TerBrugge KG, Krings T. Impact of anatomical variations of the circle of Willis on the incidence of aneurysms and their recurrence rate following endovascular treatment. Clin Radiol. 2010;65:895–901. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Rooij NK, Velthuis BK, Algra A, Rinkel GJ. Configuration of the circle of Willis, direction of flow, and shape of the aneurysm as risk factors for rupture of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurol. 2009;256:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stojanović N, Stefanović I, Randjelović S, Mitić R, Bosnjaković P, Stojanov D. Presence of anatomical variations of the circle of Willis in patients undergoing surgical treatment for ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2009;66:711–7. doi: 10.2298/vsp0909711s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krasny A, Nensa F, Sandalcioglu IE, Göricke SL, Wanke I, Gramsch C, et al. Association of aneurysms and variation of the A1 segment. J Neurointerv Surg. 2014;6:178–83. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2013-010669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rinaldo L, McCutcheon BA, Snyder KA, Porter AL, Bydon M, Lanzino G, et al. A1 segment hypoplasia associated with cerebral infarction after anterior communicating artery aneurysm rupture. J Neurosurg Sci. 2019;63:359–64. doi: 10.23736/S0390-5616.16.03778-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moritz A, Koci G, Steinlechner B, Hölzenbein T, Nasel C, Grubhofer G, et al. Contralateral stroke during carotid endarterectomy due to abnormalities in the circle of Willis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;119:669–73. doi: 10.1007/s00508-007-0837-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chuang YM, Liu CY, Pan PJ, Lin CP. Posterior communicating artery hypoplasia as a risk factor for acute ischemic stroke in the absence of carotid artery occlusion. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:1376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lochner P, Golaszewski S, Caleri F, Ladurner G, Tezzon F, Zuccoli G, et al. Posterior circulation ischemia in patients with fetal-type circle of Willis and hypoplastic vertebrobasilar system. Neurol Sci. 2011;32:1143–6. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0763-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyazawa N, Shinohara T, Yamagata Z. Association of incompleteness of the anterior part of the circle of Willis with the occurrence of lacunes in the basal ganglia. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:1358–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arjal RK, Zhu T, Zhou Y. The study of fetal-type posterior cerebral circulation on multislice CT angiography and its influence on cerebral ischemic strokes. Clin Imaging. 2014;38:221–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan DJ, Byrne S, Dunne R, Harmon M, Harbison J. White matter disease and an incomplete circle of Willis. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:547–52. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Seeters T, Hendrikse J, Biessels GJ, Velthuis BK, Mali WP, Kappelle LJ, et al. Completeness of the circle of Willis and risk of ischemic stroke in patients without cerebrovascular disease. Neuroradiology. 2015;57:1247–51. doi: 10.1007/s00234-015-1589-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leng X, Lan L, Liu L, Leung TW, Wong KS. Good collateral circulation predicts favorable outcomes in intravenous thrombolysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23:1738–49. doi: 10.1111/ene.13111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fanou EM, Knight J, Aviv RI, Hojjat SP, Symons SP, Zhang L, et al. Effect of collaterals on clinical presentation, Baseline Imaging, complications, and outcome in acute stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:2285–91. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaninovich OA, Ramey WL, Walter CM, Dumont TM. Completion of the Circle of Willis varies by gender, age, and indication for computed tomography angiography. World Neurosurg. 2017;106:953–63. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.07.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Writing Group Members, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghods AJ, Lopes D, Chen M. Gender differences in cerebral aneurysm location. Front Neurol. 2012;3:78. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindner SH, Bor AS, Rinkel GJ. Differences in risk factors according to the site of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:116–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.163063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han A, Yoon DY, Chang SK, Lim KJ, Cho BM, Shin YC, et al. Accuracy of CT angiography in the assessment of the circle of Willis: Comparison of volume-rendered images and digital subtraction angiography. Acta Radiol. 2011;52:889–93. doi: 10.1258/ar.2011.110223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stock KW, Wetzel S, Kirsch E, Bongartz G, Steinbrich W, Radue EW. Anatomic evaluation of the circle of Willis: MR angiography versus intraarterial digital subtraction angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:1495–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patrux B, Laissy JP, Jouini S, Kawiecki W, Coty P, Thiébot J. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the circle of Willis: A prospective comparison with conventional angiography in 54 subjects. Neuroradiology. 1994;36:193–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00588129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faber JE, Zhang H, Rzechorzek W, Dai KZ, Summers BT, Blazek C, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to variation in the posterior communicating collaterals of the circle of Willis. Transl Stroke Res. 2019;10:189–203. doi: 10.1007/s12975-018-0626-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sánchez van Kammen M, Moomaw CJ, van der Schaaf IC, Brown RD, Jr, Woo D, Broderick JP, et al. Heritability of circle of Willis variations in families with intracranial aneurysms. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Larson MG, Massaro JM, Vasan RS. Predicting the 30-year risk of cardiovascular disease: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2009;119:3078–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.816694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macchi C, Catini C, Federico C, Gulisano M, Pacini P, Cecchi F, et al. Magnetic resonance angiographic evaluation of circulus arteriosus cerebri (circle of Willis): A morphologic study in 100 human healthy subjects. Ital J Anat Embryol. 1996;101:115–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krabbe-Hartkamp MJ, van der Grond J, de Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Algra A, Hillen B, et al. Circle of Willis: Morphologic variation on three-dimensional time-of-flight MR angiograms. Radiology. 1998;207:103–11. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.1.9530305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartkamp MJ, van Der Grond J, van Everdingen KJ, Hillen B, Mali WP. Circle of Willis collateral flow investigated by magnetic resonance angiography. Stroke. 1999;30:2671–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.12.2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horikoshi T, Akiyama I, Yamagata Z, Sugita M, Nukui H. Magnetic resonance angiographic evidence of sex-linked variations in the circle of Willis and the occurrence of cerebral aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:697–703. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.4.0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malamateniou C, Adams ME, Srinivasan L, Allsop JM, Counsell SJ, Cowan FM, et al. The anatomic variations of the circle of Willis in preterm-at-term and term-born infants: An MR angiography study at 3T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1955–62. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Q, Li J, Lv F, Li K, Luo T, Xie P. A multidetector CT angiography study of variations in the circle of Willis in a Chinese population. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:379–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.07.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanaka H, Fujita N, Enoki T, Matsumoto K, Watanabe Y, Murase K, et al. Relationship between variations in the circle of Willis and flow rates in internal carotid and basilar arteries determined by means of magnetic resonance imaging with semiautomated lumen segmentation: Reference data from 125 healthy volunteers. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:1770–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naveen SR, Bhat V, Karthik GA. Magnetic resonance angiographic evaluation of circle of Willis: A morphologic study in a tertiary hospital set up. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2015;18:391–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.165453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin ZN, Dong WT, Cai XW, Zhang Z, Zhang LT, Gao F, et al. CTA characteristics of the circle of Willis and intracranial aneurysm in a Chinese crowd with family history of stroke. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2016/1743794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karatas A, Coban G, Cinar C, Oran I, Uz A. Assessment of the circle of Willis with cranial tomography angiography. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:2647–52. doi: 10.12659/MSM.894322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaikh R, Sohail S. MRA-based evaluation of anatomical variation of circle of Willis in adult Pakistanis. J Pak Med Assoc. 2018;68:187–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeniçeri IÖ, Çullu N, Deveer M, Yeniçeri EN. Circle of Willis variations and artery diameter measurements in the Turkish population. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 2017;76:420–5. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2017.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orlandini GE, Ruggiero C, Orlandini SZ, Gulisano M. Blood vessel size of circulus arteriosus cerebri (circle of Willis): A statistical research on 100 human subjects. Acta Anat (Basel) 1985;123:72–6. doi: 10.1159/000146042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kapoor K, Singh B, Dewan LI. Variations in the configuration of the circle of Willis. Anat Sci Int. 2008;83:96–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-073X.2007.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eftekhar B, Dadmehr M, Ansari S, Ghodsi M, Nazparvar B, Ketabchi E. Are the distributions of variations of circle of Willis different in different populations.– Results of an anatomical study and review of literature? BMC Neurol. 2006;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Silva KR, Silva R, Amaratunga D, Gunasekera WS, Jayesekera RW. Types of the cerebral arterial circle (circle of Willis) in a Sri Lankan population. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hashemi SM, Mahmoodi R, Amirjamshidi A. Variations in the Anatomy of the Willis' circle: A 3-year cross-sectional study from Iran (2006-2009). Are the distributions of variations of circle of Willis different in different populations? Result of an anatomical study and review of literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4:65. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.112185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gunnal SA, Farooqui MS, Wabale RN. Anatomical variations of the circulus arteriosus in cadaveric human brains. Neurol Res Int. 2014;2014:1–16. doi: 10.1155/2014/687281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klimek-Piotrowska W, Rybicka M, Wojnarska A, Wójtowicz A, Koziej M, Hołda MK. A multitude of variations in the configuration of the circle of Willis: An autopsy study. Anat Sci Int. 2016;91:325–33. doi: 10.1007/s12565-015-0301-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karatas A, Yilmaz H, Coban G, Koker M, Uz A. The Anatomy of circulus arteriosus cerebri (Circle of Willis): A study in Turkish population. Turk Neurosurg. 2016;26:54–61. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.13281-14.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lambert SL, Williams FJ, Oganisyan ZZ, Branch LA, Mader EC., Jr Fetal-type variants of the posterior cerebral Artery and concurrent infarction in the major arterial territories of the cerebral hemisphere. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2016;4:1–3. doi: 10.1177/2324709616665409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forgo B, Tarnoki AD, Tarnoki DL, Kovacs DT, Szalontai L, Persely A, et al. Are the Variants of the circle of Willis determined by genetic or environmental factors? Results of a twin study and review of the literature. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2018;21:384–93. doi: 10.1017/thg.2018.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Macchi C, Lova RM, Miniati B, Gulisano M, Pratesi C, Conti AA, et al. The circle of Willis in healthy older persons. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2002;43:887–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Del Brutto OH, Lama J. Variants in the circle of Willis and white matter disease in Ecuadorian mestizos. J Neuroimaging. 2015;25:124–6. doi: 10.1111/jon.12077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Del Brutto OH, Mera RM, Zambrano M, Lama J. Incompleteness of the circle of Willis correlates poorly with imaging evidence of small vessel disease. A population-based study in rural Ecuador (the Atahualpa project) J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:73–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Varga A, Di Leo G, Banga PV, Csobay-Novák C, Kolossváry M, Maurovich-Horvat P, et al. Multidetector CT angiography of the circle of Willis: Association of its variants with carotid artery disease and brain ischemia. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:46–56. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5577-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]