Abstract

Background

Aversion therapy pairs the pleasurable stimulus of smoking a cigarette with some unpleasant stimulus. The objective is to extinguish the urge to smoke.

Objectives

This review has two aims: First, to determine the efficacy of rapid smoking and other aversive methods in helping smokers to stop smoking; Second, to determine whether there is a dose‐response effect on smoking cessation at different levels of aversive stimulation.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group specialised register (latest search date October 2009) for studies which evaluated any technique of aversive smoking.

Selection criteria

Randomized trials which compared aversion treatments with 'inactive' procedures or which compared aversion treatments of different intensity for smoking cessation. Trials must have reported follow up of least six months from beginning of treatment.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data in duplicate on the study population, the type of aversion treatment, the outcome measure, method of randomization and completeness of follow up.

The outcome measure was abstinence from smoking at maximum follow up, using the strictest measure reported by the authors. Subjects lost to follow up were regarded as smokers. Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis using a fixed effect model.

Main results

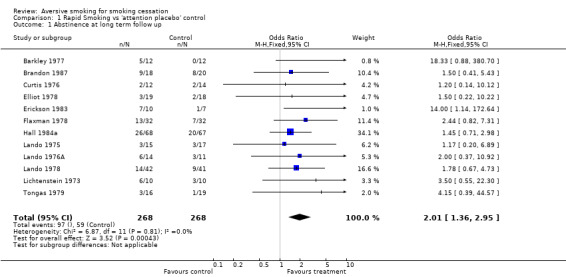

Twenty‐five trials met the inclusion criteria. Twelve included rapid smoking and nine used other aversion methods. Ten trials included two or more conditions allowing assessment of a dose‐response to aversive stimulation. The odds ratio (OR) for abstinence following rapid smoking compared to control was 2.01 (95% confidence intervals (CI): 1.36 to 2.95). Several factors suggest that this finding should be interpreted cautiously. A funnel plot of included studies was asymmetric, due to the relative absence of small studies with negative results. Most trials had a number of serious methodological problems likely to lead to spurious positive results. The only trial using biochemical validation of all self reported cessation gave a non‐significant result.

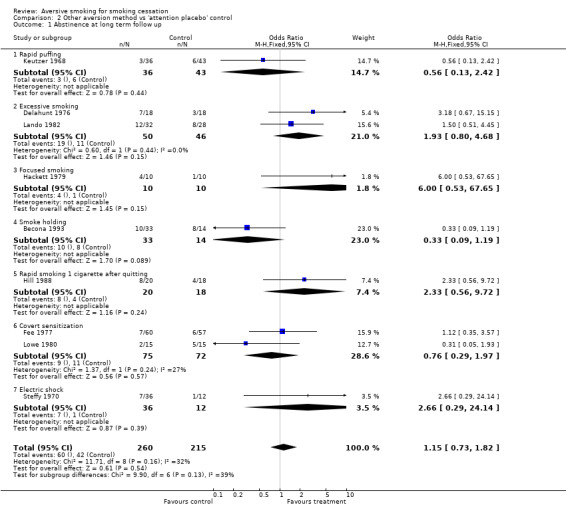

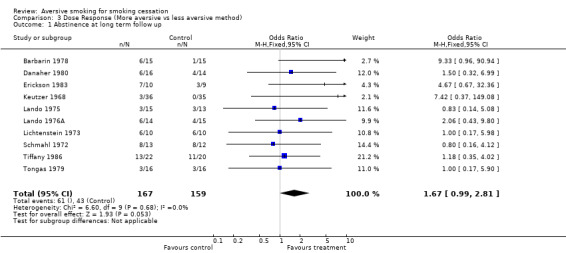

Other aversion methods were not shown to be effective (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.82). There was a borderline dose‐response to the level of aversive stimulation (OR 1.67, 95% CI 0.99 to 2.81).

Authors' conclusions

The existing studies provide insufficient evidence to determine the efficacy of rapid smoking, or whether there is a dose‐response to aversive stimulation. Milder versions of aversive smoking seem to lack specific efficacy. Rapid smoking is an unproven method with sufficient indications of promise to warrant evaluation using modern rigorous methodology.

Plain language summary

Does smoking in a way that is unpleasant help smokers to quit

Aversion treatments pair undesirable behaviours with negative sensations. In smoking cessation, several approaches have been suggested such as rapid smoking, which requires smokers to take a puff every few seconds to make smoking unpleasant. The results of the existing trials suggest that this may be effective, but the evidence is not conclusive because most of the studies of this approach have methodological problems. A recent laboratory study also suggests that the method has an active ingredient. Further research may be worthwhile.

Background

Aversion methods have been used in attempts to modify a range of behavioural disorders, such as addictions, overeating, and paraphilias (Davison 1994). These methods are based on findings originating in animal 'classical conditioning' experiments confirming the common‐sense intuition that adding an unpleasant (aversive) stimulus to an attractive stimulus or a behaviour reduces the attractiveness of the stimulus and may extinguish the behaviour. The first report of the use of an aversion method with smokers seems to have been a 1964 paper by Wilde on blowing warm stale smoke in subjects' faces while they smoked (Wilde 1964). Following this, several other aversion procedures were developed.

The most frequently examined procedure has been rapid smoking. It was first reported by Lublin and Joslyn (Lublin 1968) who combined Wilde's procedure with asking subjects to smoke at an increased rate. Wilde's procedure gradually disappeared after a study looking at the specific contribution of the smoky air suggested that it did not affect the outcome (Lichtenstein 1973). The version of rapid smoking evaluated in most trials consists of asking subjects to take a puff every six to ten seconds. They smoke for three minutes, or until they either consume three cigarettes or feel unable to continue. After a period of rest this procedure is repeated two or three times. During rapid smoking subjects are asked to concentrate on the unpleasant sensations it causes. Various studies used from three to ten sessions of rapid smoking spread over one to four weeks. Sessions are usually individual, but sometimes take place in small groups. Subjects are usually asked not to smoke between sessions. Rapid smoking is typically accompanied by an explanation of the rationale of the method, and supportive counselling.

The main reasons for developing alternatives to rapid smoking were concerns about a risk of nicotine poisoning, myocardial ischemia, and cardiac arrhythmia (Horan 1977), although these concerns are now considered largely unfounded (Hall 1984; Russell 1978). Despite the negative image of aversive methods in general, rapid smoking seems to pose few safety and acceptability problems. Danaher 1977a quotes an estimate that at least 35,000 smokers had used the procedure with only rare reports of temporary negative effects. Clients also seem to readily accept the rationale of the method. None of the numerous studies mention any problems with patient recruitment. (This may be changing though, as nowadays pharmacological methods may be seen to offer a less demanding option). The alternative 'milder' methods, which use smoking itself as an aversive stimulus are described below.

Paced smoking is a similar procedure where inter‐puff interval is increased to 30 seconds, which does not by itself elicit aversive sensations. In some studies this has been used as an inactive control (e.g. Hall 1984a).

Self paced smoking (Lando 1976A) or focused smoking (Hackett 1979) is a procedure where subjects smoke at their own pace focusing on negative sensations.

Rapid puffing differs from rapid smoking in that subjects are asked not to inhale. This provides some unpleasant stimulation, but not the central malaise (e.g. Erickson 1983).

Covert sensitization or symbolic aversion involves imagining aversive consequences of smoking such as nausea and vomiting, and the relief following putting out the cigarette (e.g. Lowe 1980).

Smoke‐holding includes asking subjects to draw smoke into their mouths and hold it there for 30 seconds while breathing through the nose and focusing on the unpleasant sensations caused by the smoke (e.g. Becona 1993).

Excessive smoking, negative practice, satiation or oversmoking involve smoking more cigarettes per day than usual between sessions. Examples include doubling cigarette consumption (Lando 1975), or increasing consumption according to various schedules, e.g. to 150% for two days, then stopping for one day, then to 200% for one day and then to quit for good (Delahunt 1976). Sometimes this has been combined with a period of continuous smoking during sessions.

Other methods have been proposed which use aversive stimuli other than smoking. They include electric shocks administered by therapists or subjects themselves (e.g. Conway 1977), self‐administered snapping of a rubber band worn around wrist (Berecz 1979), and a combination of electric shocks and behavioural treatments with bitter pills taken prior to smoking (Whitman 1969, Whitman 1972).

Another method using the aversion principle is the application of silver acetate. This chemical combines with smokers' saliva to create an unpleasant taste in the mouth. Because it is a pharmacotherapeutic agent marketed for self administration outside formal behavioural treatments, it has been covered in a separate review (Lancaster 1997).

The body of research on aversion smoking is probably larger than that on any other single psychological method of helping people stop smoking. It was last reviewed in detail 20 years ago (Danaher 1977a). That review noted that newer studies were yielding poorer results than the original ones, but concluded that rapid smoking is effective. In a recent meta‐analysis of 188 randomized controlled trials of all smoking cessation treatments (Law 1995), 14 aversion smoking trials were included. These showed an overall significant effect, although the review emphasized that two of the trials which included biochemical validation of outcome had negative results (one however was not a randomized trial). Most studies of aversion treatments are multifactorial with more than two comparison groups, but the review did not specify how this was this handled.

Objectives

1. To evaluate the effectiveness of rapid smoking in helping smokers stop smoking for at least six months. 2. To evaluate the effectiveness of other methods of aversion smoking. 3. To see whether the degree of aversive stimulation affects outcome (dose‐response).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled studies where intervention and control groups differ in presence or intensity of aversion treatment, but not in therapist contact or other treatment ingredients.

Types of participants

Any smokers.

Types of interventions

Any non‐pharmacological aversion treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Abstinence from smoking at least six months from beginning of treatment. Trials with shorter follow up were excluded. Although biochemically validated abstinence at each follow up is the gold standard for research, self reported point prevalence abstinence was extracted if no other measure was reported.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Tobacco Addiction Group's specialised register of trials was searched for studies which evaluated the effect of any aversion technique in any treatment arm (most recent search January 2009). We made an additional search of Psychological Abstracts (PsycINFO) via OVID (1974 ‐ October week 1 2009, using the combination of free text terms; 'smoking' and ('avers*' or 'rapid'). Trials were also identified via handsearch activities co‐ordinated by the UK Cochrane Centre. The following behavioural science journals have been covered: Behaviour Research and Therapy to 1979, Behavior Therapy to 1996, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1968‐1979 and Journal of Behavioural Medicine 1978‐1996. Handsearch of these resulted in two additional trials being included. In addition the bibliographies of reviews and studies were checked. We made no attempt to obtain unpublished theses, dissertations and conference presentations, since these are among the 'grey literature' routinely searched for the Tobacco Addiction Group's specialised register.

Data collection and analysis

Each study was considered for inclusion independently by LS and PH. Where necessary, authors were contacted to clarify issues such as randomization and missing data. Most of the aversion smoking studies included several comparison groups of different types. The inclusion of comparison groups was determined by the rules below.

1. No treatment controls

The task of the review was to see if aversion therapy has a specific effect, i.e. an effect over and above non‐specific factors inherent in therapist contact. Comparisons of aversion treatment with no treatment were not included. In most studies there were 'attention placebo' or other controls roughly matched for therapist contact, although in a few the aversion treatment subjects had up to twice as many treatment sessions as controls.

2. Alternative treatments presumed active

In some studies, the aversion treatment was compared with alternative treatments also presumed active. The review included such groups only in a four‐groups factorial design, in which no evidence of a statistical treatment group interaction was reported. The attention placebo control group and the alternative 'active' treatment group could then be combined and compared with the aversion treatment group combined with 'aversion plus alternative active treatment' group. The logic of this is that the aversion treatment is adding the aversion element to the attention placebo condition, while the aversion plus alternative treatment is adding the aversion element to the alternative treatment condition.

If there were only three groups, i.e. attention placebo control, aversion, and an alternative 'active' treatment, only the control and aversion groups were compared.

Where the three groups were aversion, alternative treatment, and the two combined, only the alternative treatment and the combined treatment were compared. This tested whether aversion adds anything to an otherwise identical format (i.e. a test of specific efficacy), rather than testing which of the two treatments is better.

3. Two or more aversion treatments of different severity

Some studies compared two or more methods of aversion treatment, differing in the intensity of aversive stimuli. They were included in a secondary analysis which aimed to examine whether there was a dose‐response to aversive stimulation. If studies included a more and a less intensive aversive treatment as well as an attention/placebo group or a combination of the two aversion treatments, the first analysis included the comparison of the most intensive aversive condition and the control condition, while the secondary analysis included a comparison of the more and the less aversive conditions. Where there were more than two aversive methods of differing intensity, the secondary analysis compared the most and the least intensive ones.

Where drop‐outs and subjects lost to follow up were excluded from the original analysis, they were reincluded and regarded as continuing smokers.

Data on the number of quitters in the treatment and control groups, and an odds ratio with confidence intervals, are presented in the Summary of Analyses. For each comparison, we calculated an estimate of the most likely effect size and its 95% confidence limits using the Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect method, in line with Cochrane Collaboration's preferred approach (Cochrane Handbook). This replaces our use of the Peto method (Yusuf 1985) in previous versions of this review.

We have included in this review the Tobacco Addiction Group glossary of tobacco‐specific terms (Appendix 1).

Results

Description of studies

A total of 68 studies of aversion treatments were identified. Of these, 25 qualified for inclusion in the meta‐analysis. Six of the included studies had multiple groups suitable for entry in two analyses. The 'Characteristics of Included Studies' table provides notes on their design and quality. There are 12 studies included in the analysis of efficacy of rapid smoking, 10 in the analysis of efficacy of other aversive methods, and nine in the analysis of difference between the efficacy of less versus more aversive methods. The most common reasons for exclusion were lack of data on abstinence rates, short follow up, a lack of appropriate comparison groups, and lack of randomized allocation. Reasons for exclusion are reported in full in the 'Characteristics of Excluded Studies' table.

The nine studies of aversive methods other than rapid smoking included rapid puffing (Keutzer 1968), excessive smoking (Delahunt 1976; Lando 1982), focused smoking (Hackett 1979), smoke holding (Becona 1993), and covert sensitization (Fee 1977; Lowe 1980). Hill 1988 used the rapid smoking of a single cigarette at the first relapse prevention session after quitting. Steffy 1970 used electric shock to the finger tips whilst the subject visualised smoking.

Risk of bias in included studies

Evaluation of psychological treatments is more difficult than evaluation of pharmacotherapies. There are problems in specifying a good control condition, and neither the subject nor the therapist are usually blind to subject allocation. Furthermore, it is generally believed that the same method can achieve different results when applied by different therapists. Studies in which different therapists run different conditions may be comparing the efficacy of the therapists rather than the efficacy of the methods. Even where the same therapist runs different treatments, the fact that the therapist is not blind and usually believes that one treatment is superior to others can introduce a 'performance bias'. The better studies try to tackle this problem by having several therapists, each running all treatments.

The objective validation of abstinence is particularly important. Establishing subjects' smoking status on the basis of a telephone conversation with a non‐blind therapist is unsatisfactory. The combination of the subject not wanting to disappoint the therapist and the therapist's keenness to hear the 'right' answer may lead to false results due to misclassification. The possibility of such bias is increased considerably by the fact that the old studies did not insist on complete abstinence and the number and timing of allowable slips were not specified. This allows unacceptable flexibility in 'allocating' (rather than establishing) smoking status. All but one of the studies included in this review lack biochemical validation of each self report of abstinence.

Only one of the studies in this review (Hall 1984a) avoids the most glaring methodological problems. All the others present most or all of the following problems: validation not done or incomplete, outcome assessor not blind to subject allocation, different therapists for different treatments or only one therapist involved, no information on continuous abstinence, and very small sample sizes (usually around 20 subjects per condition). Most of these methodological shortcomings can be expected to influence the results in favour of the treatment's efficacy. In the absence of validation and continuous abstinence data, the various (unintentional) therapist biases can affect subject self reports and their interpretation. The small sample sizes make studies liable to publication bias in that small studies stand a better chance of being submitted and published if their results are positive, while large trials tend to be published regardless of their results.

The poor methodological quality of this body of literature is explained by its age. The methodology of research in smoking cessation has developed considerably over the last 10 to 15 years. Most aversive treatment studies are over 20 years old.

Effects of interventions

For trials of rapid smoking, the pooled odds ratio (OR) of 12 studies included in the analysis is 2.01 with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of 1.36 to 2.95 (comparison 1.1), suggesting that rapid smoking is effective in aiding smoking cessation. However the single study fulfilling current criteria for methodological adequacy yielded only a non‐significant trend, while methodologically less adequate small studies tended to report better results.

Other aversive methods did not differ significantly from control procedures (OR 1.15, 95% CI: 0.73 to 1.82; comparison 2.1), and there was a borderline 'dose response' to the severity of aversive stimulation (OR 1.67, 95% CI: 0.99 to 2.81; comparison 3.1).

In view of the dearth of modern literature on rapid smoking, two recent studies deserve a mention here, although they contribute to the topic of this review only indirectly. Juliano 2006 evaluated rapid smoking in salvaging the quit attempt of smokers undergoing intensive treatment with counselling and bupropion who relapsed back to smoking early on in treatment. The sample (16 in the rapid smoking and 14 in the control group) was too small to detect any realistic effect, but the fact that all but one patients returned to smoking by six months suggests that rapid smoking lacks efficacy with this very difficult target group. McRobbie 2007 randomized 100 smokers at the start of their quit attempt to rapid smoking or educational intervention and detected a significant effect on urges to smoke over the first week of abstinence. The trialists interpret the finding as suggesting that the procedure has an active ingredient in craving reduction.

Discussion

The results of the meta‐analyses imply that rapid smoking has significant specific efficacy, that other aversive methods do not, and that there is borderline evidence that increasing the severity of aversive stimulation affects outcome. These statistical results must be interpreted in the light of methodological considerations before drawing final conclusions.

1. Rapid smoking

Out of twelve studies only one included biochemical validation (Hall 1984a). This is the most recent study in this group, with by far the largest sample. The rapid smoking and control subjects did not differ in outcome, although there was a trend in the expected direction (38% versus 30% abstainers in the intervention and control groups respectively at 12 months, NS). Almost all of the remaining small unvalidated studies show larger effects than this. Logically the results with small samples should spread symmetrically around the 'true' mean. This 'funnel plot' argument (Egger 1995) suggests a bias such as selective non‐publication of negative results. We have discussed earlier how, in addition to a possible publication bias, the methodological shortcomings of the older studies (such as allocating smoking status on the basis of non‐blind unvalidated interviews) were also likely to lead to false positive results. It would thus not seem appropriate to conclude that there is evidence for efficacy of rapid smoking. Yet the existing results and in particular the positive trend in the best study so far warrant further investigation. We conclude that the efficacy of rapid smoking is unknown, but that there is a case for its proper evaluation using the current more rigorous methodology.

2. Other aversion methods

If we distrust the positive result due to methodological inadequacy of the studies, why trust a negative result based on studies of a similar standard? The reasons why it is easier to accept the result of this meta‐analysis at face value are the following: Firstly, all the methods included were 'softer' variations of aversive smoking (e.g. smoke‐holding, rapid puffing, negative practice, covert sensitization, rapid smoking of one cigarette only, and scheduled smoking). Their presumed active ingredient was the same as in rapid smoking, but diluted to make them safer. Although theoretically they may differ in efficacy, they would not be expected to be more effective than rapid smoking. Secondly, the biases identified earlier favour spurious positive rather than spurious negative findings.

3. Degree of aversive stimulation

All studies in this group included rapid smoking as one of the comparison groups. The lack of positive results may seem to further undermine the finding of specific efficacy of rapid smoking, i.e. if the non‐rapid smoking methods are not effective and they do not differ from rapid smoking, rapid smoking is unlikely to be effective either. However, none of the studies included in this analysis had a reasonable chance to detect the expected small difference between treatment programmes differing only in one relatively small detail (e.g. presence of warm smoky air). When all the studies are combined, the pooled sample still includes only just over 150 subjects in each of the two comparison conditions. Even if rapid smoking does have a true specific efficacy of 14% and the milder versions of aversion smoking lower this to 7%, the total sample size of the ten studies has only about 50% power (one‐tailed test) to detect this difference. The conclusion is that so far the dose response to aversive stimulation in terms of abstinence rates has not been adequately tested.

General comments.

There is a striking contrast between the relatively large number of publications intending to evaluate aversive smoking (over 60 papers, mostly in reputable refereed journals) and the very modest conclusions they afford. This is primarily due to the inadequacy of the methodology of smoking cessation studies from the 1970s and the beginning of 1980s when aversive smoking was a fashionable research topic. However, the crucial methodological developments including techniques for objective validation of self‐reported smoking status, a recognition of the importance of sample size, and longer follow ups, became widespread only over the last 10 to 15 years, coinciding with a diminishing interest in aversive smoking. As already noted, only one of the studies of rapid smoking included full biochemical validation. Sample size was also small; 15 of the 21 studies had fewer than 20 subjects per group. By comparison, among trials considered in the review of efficacy of nicotine replacement (Stead 2008), almost all used biochemical validation and none had less than 20 subjects per group. The total number of subjects included is over 22,000. There is a clear need to revisit promising behavioural treatments such as rapid smoking which were never adequately examined, and evaluate them again using the current methodology.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The existing studies provide insufficient evidence of the efficacy of rapid smoking. A dose‐response to aversion stimulation has not been clearly demonstrated, but existing data do not allow an unequivocal conclusion here either. Milder versions of 'aversion smoking' seem ineffective.

Implications for research.

In the current era of pharmacological treatments for smoking, research in behavioural methods has declined considerably despite the acknowledged need for behavioural accompaniments to drug therapies. Rapid smoking remains an unproven method with sufficient indications of promise to warrant evaluation using modern rigorous methodology.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 June 2011 | Amended | Additional table converted to appendix to correct pdf format |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1997 Review first published: Issue 4, 1997

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 October 2009 | New search has been performed | Search updated, no new included studies, published reference added for one study Already excluded (now McRobbie 2007). |

| 4 November 2008 | Amended | History event changed to correct date of last citation issue |

| 8 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 30 July 2007 | Amended | Inconsistencies between odds ratios in the abstract and those in the main text corrected. |

| 23 May 2007 | New search has been performed | Search updated, no new included trials, 2 new excluded. |

| 9 May 2004 | New citation required and minor changes | Search updated for issue 3, 2004. No new trials found. |

| 29 May 2001 | New citation required and minor changes | Search updated for issue 3, 2001. One study added (Curtis 1976), not identified at the time of the original review. |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Drs. Martin Raw and Harry Lando for providing additional information to clarify published data, and to Dr Tim Lancaster for assisting with checking data extraction. We thank Dr Julia Critchley for drawing our attention to statistical inconsistencies between abstract and text in the 2007 update.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

| Abstinence | A period of being quit, i.e. stopping the use of cigarettes or other tobacco products, May be defined in various ways; see also: point prevalence abstinence; prolonged abstinence; continuous/sustained abstinence |

| Biochemical verification | Also called 'biochemical validation' or 'biochemical confirmation': A procedure for checking a tobacco user's report that he or she has not smoked or used tobacco. It can be measured by testing levels of nicotine or cotinine or other chemicals in blood, urine, or saliva, or by measuring levels of carbon monoxide in exhaled breath or in blood. |

| Bupropion | A pharmaceutical drug originally developed as an antidepressant, but now also licensed for smoking cessation; trade names Zyban, Wellbutrin (when prescribed as an antidepressant) |

| Carbon monoxide (CO) | A colourless, odourless highly poisonous gas found in tobacco smoke and in the lungs of people who have recently smoked, or (in smaller amounts) in people who have been exposed to tobacco smoke. May be used for biochemical verification of abstinence. |

| Cessation | Also called 'quitting' The goal of treatment to help people achieve abstinence from smoking or other tobacco use, also used to describe the process of changing the behaviour |

| Continuous abstinence | Also called 'sustained abstinence' A measure of cessation often used in clinical trials involving avoidance of all tobacco use since the quit day until the time the assessment is made. The definition occasionally allows for lapses. This is the most rigorous measure of abstinence |

| 'Cold Turkey' | Quitting abruptly, and/or quitting without behavioural or pharmaceutical support. |

| Craving | A very intense urge or desire [to smoke]. See: Shiffman et al 'Recommendations for the assessment of tobacco craving and withdrawal in smoking cessation trials' Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2004: 6(4): 599‐614 |

| Dopamine | A neurotransmitter in the brain which regulates mood, attention, pleasure, reward, motivation and movement |

| Efficacy | Also called 'treatment effect' or 'effect size': The difference in outcome between the experimental and control groups |

| Harm reduction | Strategies to reduce harm caused by continued tobacco/nicotine use, such as reducing the number of cigarettes smoked, or switching to different brands or products, e.g. potentially reduced exposure products (PREPs), smokeless tobacco. |

| Lapse/slip | Terms sometimes used for a return to tobacco use after a period of abstinence. A lapse or slip might be defined as a puff or two on a cigarette. This may proceed to relapse, or abstinence may be regained. Some definitions of continuous, sustained or prolonged abstinence require complete abstinence, but some allow for a limited number or duration of slips. People who lapse are very likely to relapse, but some treatments may have their effect by helping people recover from a lapse. |

| nAChR | [neural nicotinic acetylcholine receptors]: Areas in the brain which are thought to respond to nicotine, forming the basis of nicotine addiction by stimulating the overflow of dopamine |

| Nicotine | An alkaloid derived from tobacco, responsible for the psychoactive and addictive effects of smoking. |

| Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) | A smoking cessation treatment in which nicotine from tobacco is replaced for a limited period by pharmaceutical nicotine. This reduces the craving and withdrawal experienced during the initial period of abstinence while users are learning to be tobacco‐free The nicotine dose can be taken through the skin, using patches, by inhaling a spray, or by mouth using gum or lozenges. |

| Outcome | Often used to describe the result being measured in trials that is of relevance to the review. For example smoking cessation is the outcome used in reviews of ways to help smokers quit. The exact outcome in terms of the definition of abstinence and the length of time that has elapsed since the quit attempt was made may vary from trial to trial. |

| Pharmacotherapy | A treatment using pharmaceutical drugs, e.g. NRT, bupropion |

| Point prevalence abstinence (PPA) | A measure of cessation based on behaviour at a particular point in time, or during a relatively brief specified period, e.g. 24 hours, 7 days. It may include a mixture of recent and long‐term quitters. cf. prolonged abstinence, continuous abstinence |

| Prolonged abstinence | A measure of cessation which typically allows a 'grace period' following the quit date (usually of about two weeks), to allow for slips/lapses during the first few days when the effect of treatment may still be emerging. See: Hughes et al 'Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations'; Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2003: 5 (1); 13‐25 |

| Relapse | A return to regular smoking after a period of abstinence |

| Secondhand smoke | Also called passive smoking or environmental tobacco smoke [ETS] A mixture of smoke exhaled by smokers and smoke released from smouldering cigarettes, cigars, pipes, bidis, etc. The smoke mixture contains gases and particulates, including nicotine, carcinogens and toxins. |

| Self‐efficacy | The belief that one will be able to change one's behaviour, e.g. to quit smoking |

| SPC [Summary of Product Characteristics] | Advice from the manufacturers of a drug, agreed with the relevant licensing authority, to enable health professionals to prescribe and use the treatment safely and effectively. |

| Tapering | A gradual decrease in dose at the end of treatment, as an alternative to abruptly stopping treatment |

| Titration | A technique of dosing at low levels at the beginning of treatment, and gradually increasing to full dose over a few days, to allow the body to get used to the drug. It is designed to limit side effects. |

| Withdrawal | A variety of behavioural, affective, cognitive and physiological symptoms, usually transient, which occur after use of an addictive drug is reduced or stopped. See: Shiffman et al 'Recommendations for the assessment of tobacco craving and withdrawal in smoking cessation trials' Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2004: 6(4): 599‐614 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Rapid Smoking vs 'attention placebo' control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abstinence at long term follow up | 12 | 536 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.01 [1.36, 2.95] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Rapid Smoking vs 'attention placebo' control, Outcome 1 Abstinence at long term follow up.

Comparison 2. Other aversion method vs 'attention placebo' control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abstinence at long term follow up | 9 | 475 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.73, 1.82] |

| 1.1 Rapid puffing | 1 | 79 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.13, 2.42] |

| 1.2 Excessive smoking | 2 | 96 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.93 [0.80, 4.68] |

| 1.3 Focused smoking | 1 | 20 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.0 [0.53, 67.65] |

| 1.4 Smoke holding | 1 | 47 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.09, 1.19] |

| 1.5 Rapid smoking 1 cigarette after quitting | 1 | 38 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.33 [0.56, 9.72] |

| 1.6 Covert sensitization | 2 | 147 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.29, 1.97] |

| 1.7 Electric shock | 1 | 48 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.66 [0.29, 24.14] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Other aversion method vs 'attention placebo' control, Outcome 1 Abstinence at long term follow up.

Comparison 3. Dose Response (More aversive vs less aversive method).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abstinence at long term follow up | 10 | 326 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.99, 2.81] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dose Response (More aversive vs less aversive method), Outcome 1 Abstinence at long term follow up.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Barbarin 1978.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: No details Treatment: Groups of 3‐7, 10 sessions over 4w | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: >1 pack. Age: 40 | |

| Interventions | 1. Rapid smoking. Puff every 6 secs. for as long as possible. 1 week self monitoring, 10x1 hour sessions over 1m, self control methods, relaxation. 2. Symbolic aversion. Imagine aversive consequences of oversmoking. All else the same. 3. 1+2 together. 4. Self help manual and 4 weekly phone calls. | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: Contacts at 2m, 3m, and 12m (probably phone) Outcome used: Abstinence at 12m. Validation: None | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 2 in Dose Response analysis. Notes: Lacks validation and outcome assessor not blind. | |

Barkley 1977.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: 3, each running one treatment Type of treatment: Groups, size not given, 7 sessions over 2w | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 15‐20/day. Age: not given | |

| Interventions | 1. Puff every 10 secs in a small room for 30 min. 7x1 hour sessions over 2w. 2. Films on dangers of smoking and discussion (attention placebo). Same number and duration of sessions. 3. Hypnosis. Same number and duration of sessions. | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 6w in person, 12w by post, 9m by phone Outcome used: Abstinence at 9m. Validation: None | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 2 in Rapid Smoking analysis (Hypnosis was an alternative 'active' treatment). 7 subjects who missed a session were reincluded in totals. Notes: Each therapist ran one treatment, no validation and outcome assessor not blind. | |

Becona 1993.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: 2, division of labour not given Treatment: Groups, size not given, 10 sessions over 4w (group 5. over 2w). All paid deposit. | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 25. Age: 34 | |

| Interventions | 1. Nicotine and cigarette fading 2. Fading plus concurrent smokeholding 3. Fading plus subsequent smokeholding 4. Smokeholding in 10 sessions over 3w 5. Smokeholding in 10 sessions over 2w | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: Not specified, but results given for 1m, 2m, 3m, 6m,and 12m Outcome used: Abstinence at 12m Validation: CO or informants ('especially at follow up'), no data on misreports. | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 2+3 vs 1 (2 and 3 differ only in starting smokeholding at the 1st or 3rd of 10 sessions) in Other Methods analysis. Notes: No info on whether each therapist ran different treatments, who did follow up and how drop‐outs were treated, results of validation, etc. Not consistently validated. | |

Brandon 1987.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: 3, counterbalanced across treatments Treatment: Groups of 3‐7 (probably), Cessation 6 sessions over 2w, maintenance 4 sessions over 12w | |

| Participants | Abstainers at the end of cessation treatment. Cigarettes/day: 27. Age: 31 | |

| Interventions | 1. Maintenance (relapse prevention): self monitoring, advice, assignment of exposure and coping exercises 2. As above plus rapid puffing 3. No maintenance | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 1m, 2m, 3m ,4m, 6m,12m by phone from non‐therapist Outcome: Abstinence at 12m Validation: By phoning 2 collaterals ‐ no results given | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 2 vs 1 in Rapid Smoking analysis (reclassified 2001/3) Notes: Not validated biochemically. Aversive procedure used post cessation. 8 randomized subjects did not achieve initial cessation and are not included in analysis as their allocation is not given. | |

Curtis 1976.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: 1 Treatment: 2 groups, 12 + 14 Orientation then 7‐9 sessions over 3w, then 4 informal meetings | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day 35. Age: 45 | |

| Interventions | 1. Rapid puffing (6 secs) for up to 15 mins for 9 sessions. Group discussion 2. Group discussion | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 1m, 3m (smoking records) 6m (telephone) Outcome: abstinence at 6m Validation: none | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 2 in Rapid Smoking analysis Notes: Not validated, rapid smoking group had more sessions | |

Danaher 1980.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: 4, no other details Treatment: Individual, 7 sessions (30 mins long) over 6w | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 28. Age: 37 | |

| Interventions | 1. Aversive smoking (probably puff every 6 secs) and relaxation. Audiotapes for home use. 2. 'Regular‐paced aversive smoking', All else the same. 3. No treatment | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 8m Outcome: Abstinence at 8m Validation: TCN and CO, done on 81%, no explanation why not all. | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 2 in Dose‐Response analysis Notes: Drop‐outs excluded, numbers not given. Insufficient validation. Important details missing. | |

Delahunt 1976.

| Methods | Randomized study 'within scheduling constraints' Therapists: All treatments run by the same therapist Treatment:Groups, size not given, 6 sessions over 3w | |

| Participants | All women. Cigarettes/day: 25. Age: 28 | |

| Interventions | 1. Smoke 1.5 times the usual rate 2 days, quit one day, twice the usual level, quit for good (negative practice). Six 1 hour sessions over 3w 2. Instruction on self control strategies, all else the same 3. Combination of 1 and 2 4. Attention control ‐ group meeting without the specific components 5. Waiting list control | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 1m, 3m, and 6m post cessation Outcome: Abstinence at 6m Validation: Saliva taken but not analysed ('bogus pipeline') | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1+3 vs 2+4 in Other Methods analysis Notes: No true validation and outcome assessor not blind. | |

Elliot 1978.

| Methods | Not clear whether randomized, subjects were 'assigned' Therapists: 5 undergraduate students, each administering different treatment Treatment: Groups of 6‐9, 9‐12 treatment sessions | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 27. Age: 29 | |

| Interventions | 1. Puff every 6 secs until had enough, 2 trials each session. 9 treatment sessions over 3w with educational intro common to all 3 groups. 2. As above plus relaxation, covert sensitization, systematic desensitization, role play, and self‐management techniques. All else the same 3. Non‐directive discussion. All else the same 4. Untreated controls (First 3 groups randomized to 3 rapid smoking booster sessions, 3 lecture booster sessions. or no booster sessions.) | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 3m and 6m Outcome: Abstinence at 6m Validation: Some subjects only checked by informers and a bogus marketing survey | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 3 in Rapid Smoking analysis Notes: No true validation, different therapists for different treatments | |

Erickson 1983.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: Graduate students, N not given, each group run by 2 Treatment: Groups of 3‐6, 2 in each condition, 6 x 90 min sessions over 2w | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 30. Age: 31 | |

| Interventions | 1. Puff every 6 secs, 3 trials per session, plus behavioural counselling 2. Puffing but not inhaling (rapid puffing), all else the same 3. Behavioural counselling, all else the same | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: Every 3m for 1 year Outcome: Abstinence at 1 year Validation: 'Collaterals' contacted for all subjects, but disagreement did not lead to subject reclassification. | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 3 in Rapid Smoking analysis, 1 vs 2 in Dose‐Response analysis Notes: Not properly validated, outcome assessor not blind, striking result on a small sample | |

Fee 1977.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: All treatments run by the author Treatment: Individual, 9w, number and duration of sessions not given | |

| Participants | 232 smokers, no further details | |

| Interventions | 1. Hypnosis 2. Covert sensitization 3. Fenfluramine 4. Placebo (details not given) | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts 9w and 1 year. Outcome; Abstinence at 1 year, no validation mentioned. | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 2 vs 4 in Other Methods analysis. | |

Flaxman 1978.

| Methods | Randomized study but partners and friends kept together Therapists: 4 psychology graduate students, each treating 8 subjects in each condition Treatment: individual (probably), about 4 treatment sessions over 11 days | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 26. Age: NS | |

| Interventions | 1. Warm smoky air; puff every 6 secs for as long as possible. Av 3.8 session over 6.2 days 2. Discussing the self control techniques taught to both groups prior to quit date. Av 4.2 session over 10.6 days | |

| Outcomes | Follow up: participants mailed post cards with daily cigarette counts weekly for 2m, phone if postcard not in, phone at 6m Outcome: Abstinence at 6m Validation: None | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 2 in Rapid Smoking analysis. Aversive procedure used post cessation. This study also manipulated pre‐cessation preparation, but the 8 cells randomization allows this to be kept separate. Duration of sessions may have been less in controls. No validation and outcome assessors not blind. | |

Hackett 1979.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: All treatments run by the same therapist Treatment: Groups of 5, 8 sessions over 5w | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: > 20. Age: 24 | |

| Interventions | 1. Contracting, advice, cue‐controlled relaxation, smoking encouraged during sessions ‐ meant as placebo for focused smoking 2. The same but focused smoking, i.e. smoking facing blank wall with therapist providing suggestions of discomforts 3. Focused smoking only | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 1m, 2m,and 6m or 9m (different for 2 study subgroups), in person Outcome: Continuous abstinence for 6m Validation: CO ‐ cut‐off point not given, misreport rates not given | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 2 vs 1 in Other Methods analysis Notes: Unclear validation, potentially detrimental 'control' procedure | |

Hall 1984a.

| Methods | Consecutive participants assigned to groups which were then randomized to treatment Therapists: 2 graduate students, each treating equal number of groups in each condition Type of treatment: Groups of 5‐6, 14 treatment sessions | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 29. Age: 36 | |

| Interventions | 1. Puff every 6 secs on 3 cigarettes, watching video of moments when uncomfortable. 12 sessions over 3w and one at w4 and one at w6. 8 of the sessions with aversive smoking and 6 with 1 of 2 types of relapse prevention. 2. Puff every 30 secs, all else the same | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: w3, 6m and 12m Outcome: Validated abstinence at 12m Validation: CO < 10ppm, plasma TCN < 85ng/mg, and confirmation from significant other | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 2 in Rapid Smoking analysis. Drop‐outs included as smokers. Notes: Continuous abstinence not given (despite this being a study of relapse). The best of the studies | |

Hill 1988.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: 3, each running all 3 conditions Treatment: groups, size not given, 3 cessation sessions with rapid smoking over 3 days, 4 maintenance sessions over 3w | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 32. Age: 44 | |

| Interventions | 1. Abstainers rapid smoked 1 cigarette at first relapse prevention session 2. Imagining rapid smoking after relapse 3. Advised to abstain and self administer rewards for abstinence | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 1w, 2m,6m,12m Outcome: Abstinence at 12m Validation: CO, but if not obtainable, informant | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 3 in Other Methods analysis. (Unclear how to classify 2) Notes: Aversive procedure used postcessation. Not fully validated, no data on continuous abstinence | |

Keutzer 1968.

| Methods | Randomized 'with consideration of evenings convenient for subjects' Therapists: All treatments run by same 2 therapists Treatment: 5 sessions over 5w, 4 in groups (group size not stated) | |

| Participants | Cigs/day: 28. Age: 40 | |

| Interventions | 1. 'Coverant control' ‐ 'high probability behaviour made contingent on anti‐smoking thoughts' 2. Image of smoking paired with holding breath for 10‐20 secs ('aversive consequence') 3. Puff every 12 secs on 3 cigarettes in a smoky room 4. Placebo 'drug' 5. Untreated controls | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 6m by posted questionnaire (reported in Lichtenstein 1969) Outcome: Abstinence at 6m Validation: None | |

| Notes | Inclusions: 3 vs 4 in Other Methods analysis, 3 vs 2 in Dose‐Response analysis Notes: No data on continuous abstinence, not validated | |

Lando 1975.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: All treatments run by the same therapist Treatment: groups of 5‐10, 6 sessions over 1w | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 32. Age: 31 | |

| Interventions | 1. Puff every 6 secs, 3x3 mins, at home do this with a portable timer. 2. Puff every 30 secs, all else the same ('control') 3. Continuous smoking for 25 mins, at home smoke twice the usual number ('excessive smoking') | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 1w, 1m, 2m and 12m Outcome: Abstinence at 12m Validation: Random sample invited for interviews and given CO test at 2m. Number/proportion attended, CO cut‐off point or results not given. | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 2 in Rapid Smoking analysis. 1 vs 3 in Dose‐Response analysis Notes: Incomplete validation, no data on continuous abstinence and outcome assessor not blind. | |

Lando 1976A.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: Psychologist and 4 undergraduate students, assignment to treatments not given Treatment: Groups of 5‐10, Minimum 7 ‐ 20 45 min treatment sessions over 4w | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 25. Age: 29 | |

| Interventions | 1. Puff every 6 secs. 3x3 mins with 8 min. breaks. 5x45‐min. sessions per week for 4w 2. Puff every 30 secs, all else the same. Considered a non aversive control 3. Smoke ad lib for 25 mins, focusing on unpleasant sensations. All else the same | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts 2w, 1m, 2m, 6m Outcome: Abstinence at 6m Validation: Info from approx. half of nominated informants | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 2 in Rapid Smoking analysis, 1 vs 3 in Dose‐Response analysis Notes: Incomplete validation, no data on continuous abstinence and outcome assessor not blind. | |

Lando 1978.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: Psychologist and 6 undergraduates, division of labour not given Treatment: groups of 7‐12. 2x45 min preparation sessions over 2w, 6 aversion sessions over 1w, 7 maintenance session over 2m. | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 33 Age: 36 | |

| Interventions | 1. 6 sec puffs for 3 mins, 3x3 min trials in 6 sessions during a week. 2. Control procedure ‐ 30 sec puffs in same format. To use also between sessions avoiding 'normal' smoking. Participants also randomized into 2 non‐aversive conditions in preparation and maintenance phase | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 1m,2m,3m,4m,6m. Outcome: Abstinence at 6m. Validation: 50% of abstainers checked with informants | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 2 in Rapid Smoking analysis Preparation and maintenance treatment conditions collapsed for analysis. Notes: Incomplete validation, no data on continuous abstinence and outcome assessor not blind. | |

Lando 1982.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: 5 psychology graduates, assignment to treatments not given Treatment: Groups of 7‐13, up to 15 sessions over 7 weeks | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 28. Age: 36 | |

| Interventions | 1. Preparation ‐ 2 sessions of scheduled smoking, pamphlet, film 2. Aversion ‐ 6 sessions over 1w with continuous 25 mins smoking (not rapid smoking). (Also urged to double daily smoking.) 3. Maintenance ‐ 7 sessions over 8w, group discussion and contracts 4. 1+2 5. 1+3 6. 2+3 7. 1+2+3 | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 1m, 2m, 3m, 6m, 9m and 12m Outcome: Abstinence 12m Validation: Informants and CO in half of subjects. Cut off points, rate of completion and results not given | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 4+6+7 vs 1+3+5 in Other Methods analysis Notes: Aversion condition had extra sessions. Incomplete validation, no data on continuous abstinence and outcome assessor not blind. | |

Lichtenstein 1973.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: 3 graduate students. Assignment to treatments not given Treatment: individual, average of 7 sessions | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 27. Age: 32 | |

| Interventions | 1. Puff every 6 secs, metronome pacing, warm smoky air until had enough. 3 consecutive days, then as required. 2. Puff every 6 secs, no smoky air. All else the same 3. Warm smoky air, smoking at own pace. All else the same 4. Smoking 2 cigarettes normally while focusing on negative effects, placebo pills. All else the same | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 2 weeks, then monthly for 6m, by phone. Outcome: Abstinence at 6m. Validation: No systematic validation, some informants provided and contacted. | |

| Notes | 1 vs 4 in Rapid Smoking analysis, 1 vs 2 in Dose‐Response analysis Notes: No systematic validation, no data on continuous abstinence and outcome assessor not blind. | |

Lowe 1980.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: not specified Treatment: Probably groups, 19 sessions (9 cessation and 10 maintenance) over 90 days | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 34. Age: 41 | |

| Interventions | 1. Self control procedures (self monitoring and relaxation training) 2. Same as 1 plus covert sensitization, 6x at each of 12 meetings | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: in person, 3m and 6m Outcome: Validated abstinence at 6m. Validation: Saliva TCN, not clear how many subjects tested, of those tested all passed | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 2 vs 1 in Other Methods analysis Notes: Some details missing, no data on continuous abstinence. Validated outcome. The paper also describes a second study which does not allow evaluation of covert sensitization (no 'inactive' treatment) | |

Schmahl 1972.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists:2 graduate students alternated, most participants saw both Treatment: Individual, average of 8 sessions, time span not given | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 29. Age: 27 | |

| Interventions | 1. Puff every 6 secs, and warm smoky air. 2. Puff every 6 secs, and warm mentholated air. All else the same | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: Phone every 2w or 4w up to 6m Outcome: Abstinence at 6m Validation: Random 9 abstainers nominated informants | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 2 in Dose‐Response analysis Notes: Drop‐outs not included and data allowing their inclusion not given. Insufficient validation. | |

Steffy 1970.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: 2 psychologists and 2 students. Psychologist alternated Treatment: 4‐8 group sessions (6 members) over 4w | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: not given. Age: 26 | |

| Interventions | 1. Electric shocks to index fingers when describing smoking, 8 sessions 2. Discussion controls, 4 sessions | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 2m and 6m Outcome: Abstinence at 6m Validation: Nominated friend during treatment, none at follow up | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 2 in Other Methods analysis Notes: No data on continuous abstinence, not validated, intervention groups had more sessions | |

Tiffany 1986.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: 2 main therapists balanced over treatments Treatment: 3 individual and 6 group (2‐6 members) sessions over 4w, up to 9 follow up interviews | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 26. Age: 31 | |

| Interventions | 1. Rapid smoking counselling, relaxation, puff every 6 secs, 3 cigarettes 3x 2. Truncated rapid smoking ‐ only one rapid smoking trial on 3 cigarettes, all else the same 3. Rapid puffing ‐ not inhaling, all else as in 1. 4. As 1, but less counselling | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: Average 7x over 6m Outcome: Abstinence at 6m Validation: Through collaterals, only some contacted, not clear if non‐validation led to subject reclassification | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 3 in Dose‐Response analysis Notes: Insufficient validation, but outcome assessor blind to participants' allocation | |

Tongas 1979.

| Methods | Randomized study Therapists: Not clear Treatment: 5 treatment and 14 maintenance sessions over 1 year (group size 8‐11) | |

| Participants | Cigarettes/day: 30. Age: 50 | |

| Interventions | 1. Puff every 3 secs or inhaling every 6 secs on 7 cigarettes 2. Imagining aversive consequences of smoking 3. Group support and lectures 4. 1+2+3 | |

| Outcomes | Follow up contacts: 6m,12m, 24m Outcome: Abstinence at 24m Validation: None | |

| Notes | Inclusion: 1 vs 3 in Rapid Smoking analysis, 1 vs 2 in Dose‐Response analysis Notes: Not validated, details of procedures not given, no data on continuous abstinence. | |

Participants: Details of cigarette consumption are minima or averages. Age is mean average for all subjects. m: months (e.g. 12m) w: weeks (e.g. 6w) CO: Carbon Monoxide TCN: thiocyanate

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Berecz 1972 | Nine weeks follow up only. |

| Berecz 1979 | Does not provide data allowing an intention to treat analysis (procedure snapping an elastic band on wrist when urge to smoke) |

| Best 1971 | No control group (only aversion subjects were followed up) |

| Best 1978 | Not randomized. |

| Carlin 1968 | No follow up, measured smoking decrease over 4 days only. |

| Claiborn 1972 | Results only state there was no significant effect, but provide no figures to calculate numbers of abstainers (procedure: doubling smoking rate) |

| Conway 1977 | Results expressed as self reported mean percentage of baseline smoking rate, gives no data on abstinence. |

| Corty 1984 | Rapid smoking compared with another treatment presumed active (response prevention). Not fully randomized. |

| Danaher 1977 | Follow up only 13 weeks. |

| Dericco 1977 | Within‐subject design looking at immediate effects on smoking rate. |

| Etringer 1984 | Study focused on effects of group cohesion. Allows a comparison of satiation and nicotine fading but no comparison with a treatment presumed less effective. |

| Glasgow 1978 | Reports no difference in numbers abstinent at 6 months, but gives no figures. |

| Grimaldi 1969 | Only 1 month follow up, abstinence data not provided |

| Hall 1983 | The aversion treatment used, puffs every 30 secs, is considered a placebo by other studies. Aversion was mixed with other methods, while the control group was also a multimodal treatment with a set of different components presumed active. |

| Hall 1984b | Not randomized, only waiting list controls. |

| Juliano 2006 | Rapid smoking to rescue lapsed quit attempts in a cessation trial of bupropion + counselling in 67 smokers. |

| Lando 1976b | Six month follow up data not reported for two aversion conditions separately. |

| Lando 1977 | Both groups included the same mild version of aversion treatment with or without the non‐aversion maintenance component. |

| Lando 1985 | There was no control group for the mild version of aversion smoking. The comparison was with other treatments presumed active, one of which had less therapist contact. |

| Levenberg 1976 | Short follow up, abstinence data not reported. Compared rapid smoking, systematic desensitization and relaxation control. |

| Lichtenstein 1977 | 2‐6 years incomplete follow ups on participants from previous studies, the two eligible studies had 6 months follow up in the original publications and are already included. |

| Marrone 1970 | Short follow up |

| Marston 1971 | Data on abstinence not reported at 6 months follow up. Comparison of stimulus satiation, hierarchical reduction, aversive pill, and cold turkey with non directive group meetings. |

| McRobbie 2007 | Follow‐up only to end of first week in a cessation RCT of 100 smokers |

| Merbaum 1979 | Not a randomized study |

| Norton 1977 | Not randomized, figures on abstinence not provided |

| Ober 1968 | Follow up only 1 month. Abstinence data not provided. Compared 'operant' conditioning, electric shock aversion, transactional analysis and no‐treatment control. |

| Pederson 1980 | Both randomized groups included rapid smoking. The group without rapid smoking was not randomized. |

| Poole 1981 | All 4 conditions included rapid smoking. |

| Raw 1980 | Not fully randomized, as men > 40 and women > 50 not allocated to aversion. |

| Relinger 1977 | Only 3 months follow up. Evaluates rapid smoking booster sessions, found no effect, abstinence data not provided (N=6 per group). |

| Resnick 1968 | Only 4 months follow up. Evaluates satiation (doubling or tripling consumption for one week and then stopping), found significant effect (N=20 per group) |

| Russell 1976 | Follow up only 6 weeks. |

| Sipich 1974 | No data on abstinence reported at 6 month follow up. Compared covert sensitization with 4 types of control group. |

| Suedfeld 1986 | No 'inactive' or 'less active' control group. |

| Sushinsky 1972 | Only 2 months follow up. Replicating Resnick 1968, found no effect of satiation (N=16 per group). |

| Sutherland 1975 | Only 3 months follow up, number of subjects per group not given, some (unclear) abstinence rates mentioned in the discussion favouring satiation. |

| Tori 1978 | Not randomized, subjects assigned to groups in part according to their medical history. |

| Wagner 1970 | Only 3 months follow up, data on abstinence not provided (covert sensitization study) |

| Walker 1985 | No 'inactive' or 'less active' group, only two almost identical versions of focused smoking compared. |

| Whitman 1969 | Only 3 months follow up, data on abstinence not provided (electric shocks and quinine) |

| Whitman 1972 | Gives no data on abstinence rates, not clear if randomized (aversive stimulus was a bitter pill to suck on before lighting a cigarette). |

| Zelman 1992 | The aversion treatment was compared with nicotine gum treatment, no control group presumed inactive. Included in Nicotine Replacement Review. |

Contributions of authors

PH and LS both contributed to data extraction and drafting of the review

Sources of support

Internal sources

Queen Mary's School of Medicine and Dentistry, UK.

Department of Primary Health Care, University of Oxford, UK.

External sources

NHS Research and Development National Cancer Programme, England, UK.

Declarations of interest

Professor Hajek is a co‐author on one of the excluded studies (McRobbie 2007).

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Barbarin 1978 {published data only}

- Barbarin O. Comparison of symbolic and overt aversion in the self‐control of smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1978;46:1569‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Barkley 1977 {published data only}

- Barkley RA, Hastings JE, Jackson TL. The effects of rapid smoking and hypnosis in the treatment of smoking behavior. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 1977;25:7‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Becona 1993 {published data only}

- Becona E, Garcia MP. Nicotine fading and smokeholding methods to smoking cessation. Psychological Reports 1993;73:779‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brandon 1987 {published data only}

- Brandon TH, Zelman DC, Baker TB. Effects of maintenance sessions on smoking relapse: delaying the inevitable?. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1987;55:780‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Curtis 1976 {published data only}

- Curtis B, Simpson DD, Cole SG. Rapid puffing as a treatment component of a community smoking program. Journal of Community Psychology 1976;4:186‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Danaher 1980 {published data only}

- Danaher BG, Jeffery RW, Zimmerman R, Nelson E. Aversive smoking using printed instructions and audiotape adjuncts. Addictive Behaviors 1980;5:353‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Delahunt 1976 {published data only}

- Delahunt J, Curran JP. Effectiveness of negative practice and self‐control techniques in the reduction of smoking behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1976;44:1002‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Elliot 1978 {published data only}

- Elliott CH, Denney DR. A multiple‐component treatment approach to smoking reduction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1978;46:1330‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Erickson 1983 {published data only}

- Erickson L, Tiffany S, Martin E, Baker T. Aversive smoking therapies: A conditioning analysis of therapeutic effectiveness. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1983;21:595‐611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fee 1977 {published data only}

- Fee WM. Searching for the simple answer to cure the smoking habit. Health and Social Service Journal 1977;87:292‐3. [Google Scholar]

Flaxman 1978 {published data only}

- Flaxman J. Quitting smoking now or later: gradual, abrupt, immediate or delayed quitting. Behavior Therapy 1978;9:260‐70. [Google Scholar]

Hackett 1979 {published data only}

- Hackett G, Horan JJ. Partial component analysis of a comprehensive smoking program. Addictive Behaviors 1979;4:259‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hall 1984a {published data only}

- Hall SM, Rugg D, Tunstall C, Jones RT. Preventing relapse to cigarette smoking by behavioral skill training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1984;52:372‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hill 1988 {published data only}

- Hill RD. Prescribing aversive relapse to enhance nonsmoking treatment gains: A pilot study. Behavior Therapy 1988;19:35‐43. [Google Scholar]

Keutzer 1968 {published data only}

- Keutzer CS. Behavior modification of smoking: the experimental investigation of diverse techniques. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1968;6:135‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein E, Keutzer CS. Experimental investigation of diverse techniques to modify smoking: a follow‐up report. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1969;7:139‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lando 1975 {published data only}

- Lando HA. A comparison of excessive and rapid smoking in the modification of chronic smoking behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1975;43:350‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lando 1976A {published data only}

- Lando HA. Self‐pacing in eliminating chronic smoking: Serendipity revisited?. Behavior Therapy 1976;7:634‐40. [Google Scholar]

Lando 1978 {published and unpublished data}

- Lando HA. Stimulus control, rapid smoking, and contractual management in the maintenance of nonsmoking. Behavior Therapy 1978;9:962‐3. [Google Scholar]

Lando 1982 {published data only}

- Lando HA. A factorial analysis of preparation, aversion , and maintenance in the elimination of smoking. Addictive Behaviors 1982;7:143‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lichtenstein 1973 {published data only}

- Lichtenstein E, Harris DE, Birchler GR, Wahl JM, Schmahl DP. Comparison of rapid smoking, warm, smoky air, and attention placebo in the modification of smoking behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1973;40:92‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lowe 1980 {published data only}

- Lowe MR, Green L, Kurtz SMS, Ashenberg ZS, Fisher EB. Self‐initiated, cue extinction, and covert sensitization procedures in smoking cessation. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 1980;3:357‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schmahl 1972 {published data only}

- Schmahl DP, Lichtenstein E, Harris DE. Successful treatment of habitual smokers with warm, smoky air and rapid smoking. Jounral of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1972;38:105‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Steffy 1970 {published data only}

- Steffy RA, Meichenbaum D, Best JA. Aversive and cognitive factors in the modification of smoking behaviour. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1970;8:115‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tiffany 1986 {published data only}

- Tiffany ST, Martin EM, Baker TB. Treatments for cigarette smoking: An evaluation of the contributions of aversion and counseling procedures. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1986;24:437‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tongas 1979 {published data only}

- Tongas P. The Kaiser‐Permanente smoking control program: Its purpose and implications. Professional Psychology 1979;10:409‐18. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Berecz 1972 {published data only}

- Berecz JM. Modification of smoking behavior through self‐administered punishment of imagined behavior: a new approach to aversion therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1972;38:244‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Berecz 1979 {published data only}

- Berecz JM. Maintenance of nonsmoking behavior through self‐administered wrist‐band aversion therapy. Behavior Therapy 1979;10:669‐75. [Google Scholar]

Best 1971 {published data only}

- Best JA, Steffy RA. Smoking modification procedures tailored to subject characteristics. Behaviour Therapy 1971;2:177‐91. [Google Scholar]

Best 1978 {published data only}

- Best JA, Owen LE, Trentadue L. Comparison of satiation and rapid smoking in self‐managed smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors 1978;3:71‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Carlin 1968 {published data only}

- Carlin AS, Armstrong HE. Aversive conditioning: learning or dissonance reduction?. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1968;32:674‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Claiborn 1972 {published data only}

- Claiborn WL, Lewis P, Humble S. Stimulus satiation and smoking: a revisit. Journal of Clinical Psychology 1972;28:416‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Conway 1977 {published data only}

- Conway JB. Behavioral self‐control of smoking through aversive conditioning and self‐management. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1977;45:348‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Corty 1984 {published data only}

- Corty E, McFall RM. Response prevention in the treatment of cigarette smoking. Addictive Behaviors 1984;9:405‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Danaher 1977 {published data only}

- Danaher BG. Rapid smoking and self‐control in the modification of smoking behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1977;45:1068‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dericco 1977 {published data only}

- Dericco D, Brigham T, Garlington W. Development and evaluation of treatment paradigms for the suppression of smoking behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 1977;10:173‐81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Etringer 1984 {published data only}

- Etringer BD, Gregory VR, Lando HA. Influence of group cohesion on the behavioral treatment of smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1984;52:1080‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Glasgow 1978 {published data only}

- Glasgow RE. Effects of a self‐control manual, rapid smoking and amount of therapist contact on smoking reduction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1978;46:1439‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Grimaldi 1969 {published data only}

- Grimaldi KE, Lichtenstein E. Hot, smoky air as an aversive stimulus in the treatment of smoking. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1969;7:275‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hall 1983 {published data only}

- Hall SM, Bachman J, Henderson JB, Barstow R, Jones RT. Smoking cessation in patients with cardiopulmonary disease: An initial study. Addictive Behaviors 1983;8:33‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hall 1984b {published data only}

- Hall RG, Sachs DP, Hall SM, Benowitz NL. Two‐year efficacy and safety of rapid smoking therapy in patients with cardiac and pulmonary disease. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1984;52:574‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Juliano 2006 {published data only}

- Juliano LM, Houtsmuller EJ, Stitzer ML. A preliminary investigation of rapid smoking as a lapse‐responsive treatment for tobacco dependence. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 2006;14(4):429‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lando 1976b {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Lando HA. Aversive conditioning and contingency management in the treatment of smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1976;44:312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lando 1977 {published data only}

- Lando HA. Successful treatment of smokers with a broad‐spectrum behavioral approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1977;45:361‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lando 1985 {published data only}

- Lando HA, McGovern PG. Nicotine fading as a nonaversive alternative in a broad‐spectrum treatment for eliminating smoking. Addictive Behaviors 1985;10:153‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Levenberg 1976 {published data only}

- Levenberg S, Wagner M. Smoking cessation: Long‐term irrelevance of mode of treatment. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 1976;7:93‐5. [Google Scholar]

Lichtenstein 1977 {published data only}

- Lichtenstein E, Rodrigues MR. Long‐term effects of rapid smoking treatment for dependent cigarette smokers. Addictive Behaviors 1977;2:109‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marrone 1970 {published data only}

- Marrone RL, Merksamer MA, Salzberg PM. A short duration group treatment of smoking behavior by stimulus saturation. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1970;8:347‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marston 1971 {published data only}

- Marston AR, McFall RM. Comparison of behavior modification approaches to smoking reduction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1971;36:153‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McRobbie 2007 {published data only}

- McRobbie H, Hajek P. Effects of rapid smoking on post‐cessation urges to smoke. Addiction 2007;102:483‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRobbie H, Hajek P. Rapid smoking: rekindling an old flame [POS2‐044]. Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 11th Annual Meeting, Prague, Czech Republic. 2005.

Merbaum 1979 {published data only}

- Merbaum M, Avimier R, Goldberg J. The relationship between aversion, group training and vomiting in the reduction of smoking behavior. Addictive Behaviors 1979;4:279‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Norton 1977 {published data only}

- Norton GR, Barske B. The role of aversion in the rapid‐smoking treatment procedure. Addictive Behaviors 1977;2:21‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ober 1968 {published data only}

- Ober DC. Modification of smoking behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1968;32:543‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pederson 1980 {published data only}

- Pederson LL, Scrimgeour WG, Lefcoe NM. Incorporation of rapid smoking in a community service smoking withdrawal program. International Journal of Addiction 1980;15:615‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Poole 1981 {published data only}

- Poole AD, Sanson‐Fisher RW, German GA. The rapid‐smoking technique: therapeutic effectiveness. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1981;19:389‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Raw 1980 {published data only}

- Raw M, Russell MAH. Rapid smoking, cue exposure and support in the modification of smoking. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1980;18:363‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Relinger 1977 {published data only}

- Relinger H, Bornstein PH, Bugge ID, Carmody TP, Zohn CJ. Utilization of adverse rapid smoking in groups: efficacy of treatment and maintenance procedures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1977;45:245‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Resnick 1968 {published data only}

- Resnick JH. Effects of stimulus satiation on the overlearned maladaptive response of cigarette smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1968;32:501‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Russell 1976 {published data only}

- Russell MAH, Armstrong E, Patel UA. Temporal contiguity in electric aversion therapy for cigarette smoking. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1976;14:103‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sipich 1974 {published data only}

- Sipich JF, Russell RK, Tobias LL. A comparison of covert sensitization and nonspecific treatment in the modification of smoking behavior. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimenta; Psychiatry 1974;5:201‐3. [Google Scholar]

Suedfeld 1986 {published data only}

- Suedfeld P, Baker‐Brown G. Restricted environmental stimulation therapy and aversive conditioning in smoking cessation: active and placebo effects. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1986;24:421‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sushinsky 1972 {published data only}

- Sushinsky LW. Expectation of future treatment, stimulus satiation, and smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1972;39:343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sutherland 1975 {published data only}

- Sutherland A, Amit Z, Golden M, Roseberger Z. Comparison of three behavioral techniques in the modification of smoking behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1975;43:443‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tori 1978 {published data only}

- Tori CD. A smoking satiation procedure with reduced medical risk. Journal of Clinical Psychology 1978;34:574‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wagner 1970 {published data only}

- Wagner MK, Bragg RA. Comparing behavior modification approaches to habit decrement‐‐smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1970;34:258‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Walker 1985 {published data only}

- Walker WB, Franzini LR. Low‐risk aversive group treatments, physiological feedback and booster sessions for smoking cessation. Behavior Therapy 1985;16:263‐74. [Google Scholar]

Whitman 1969 {published data only}

- Whitman TL. Modification of chronic smoking behavior: A comparison of three approaches. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1969;7:257‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]