Abstract

Objective

Despite concern regarding high rates of mental illness and suicide amongst the medical profession, the link between working hours and doctors’ mental health remains unclear. This study examines the relationship between average weekly working hours and junior doctors’ (JDs’) mental health in Australia.

Design and participants

A randomly selected sample of 42 942 Australian doctors were invited to take part in an anonymous Beyondblue National Mental Health Survey in 2013, of whom 12 252 doctors provided valid data (response rate approximately 27%). The sample of interest comprised 2706 full-time graduate medical trainees in various specialties, at either intern, prevocational or vocational training stage. Consultants and retired doctors were excluded.

Outcome measures

Main outcomes of interest were caseness of common mental disorder (CMD) (assessed using a cut-off of 4 as a threshold on total General Health Questionnaire-28 score), presence of suicidal ideation (SI) (assessed with a single item) and average weekly working hours. Logistic regression modelling was used to account for the impact of age, gender, stage of training, location of work, specialty, marital status and whether JDs had trained outside Australia.

Results

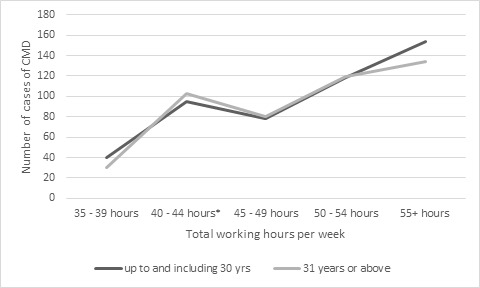

JDs reported working an average of 50.1 hours per week (SD=13.4). JDs who worked over 55 hours a week were more than twice as likely to report CMD (adjusted OR=2.05; 95% CI 1.62 to 2.59, p<0.001) and SI (adjusted OR=2.00; 95% CI 1.42 to 2.81, p<0.001) compared to those working 40–44 hours per week.

Conclusions

Our results show that around one in four JDs are currently working hours that are associated with a doubling of their risk of common mental health problems and SI. These findings suggest that management of working hours represents an important focus for workplaces to improve the mental health of medical trainees.

Keywords: mental disorder, suicide, physicians, doctors, mental health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Existing evidence on working hours and doctors mental health is limited, and the relationship between weekly working hours and common mental disorders and suicide among junior doctors (JDs) remains unclear.

Limitations of the study include its use of self-reported data and low response rate. The use of cross-sectional data means that neither causation nor reverse causation can be determined.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between clinical indicators of mental health and weekly working hours in Australian medical trainees.

This study adds value to the existing evidence by presenting findings from an under-researched group and highlights the importance of long working hours in the mental health of JDs.

Introduction

For many years, it had been assumed that long working hours were an inevitable part of a career in medicine. However, increasing concern about the potential mental health impacts of extended working hours and performance issues associated with fatigue have caused many countries to reconsider the hours that doctors are allowed to work. Long working hours has been identified as a risk factor for mental ill-health in the general population,1 for example, working 11 hours a day has been found to predict new-onset depression in healthy employees.2 Similarly, working 55 hours in total per week has been found to be a risk factor for development of anxiety and depressive symptoms.3 However, results have been mixed in general workers4 and in doctors,5 and there has been some suggestion of gender differences4 6 which require further investigation. The evidence for what role working hours plays in understanding doctors’ mental ill-health is limited and inconsistent.7 8 Within medicine there has often been an assumption that working long hours is an essential part of the job, especially during specialist training. Indeed, at times there has been a suggestion that any attempts to reduce or restrict junior doctors’ (JDs’) working hours would limit their training opportunities. Given this established culture around the importance of long working hours, it remains unclear if the evidence from the general working population on the impact of working hours on mental health are relevant for doctors.

In recent years, many countries have legislated specific work-hour restrictions for JDs,9 such as the 48 hours maximum workweek introduced under the European Working Time Directive in Europe in 200010 and an 80 hours workweek for all US residents, among other restrictions, instituted by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education in July 2011.11 These reductions in JDs working hours has been accompanied by ongoing debate about the consequences on patient care10 12 and on the quality of training.13 14 In contrast, in Australia trainee working hours are not restricted in legislation, but are instead determined by negotiated regional employment contracts that operate under different employment award conditions in each state.15 The level to which these regulated contracted hours are enforced across each hospital is a separate issue, yet the Australian Medical Association’s voluntary National Code of Practice (2016) guidelines recommends 50 hours a week as a threshold for ‘unsafe’ hours.16 17 Despite this, to date there is no nationally specified maximum working hour limit in Australia. Within this context, JDs in Australia work a wide range of hours under a variety of roster and shift structures15 with the majority comprising a 76–80 hours working fortnight and an 8-hour break between shifts.18 As a result, data from Australia are able to provide a unique insight into the relationship between a spectrum of working hours and the mental health of doctors. This study aimed to examine the relationship between average weekly working hours, common mental disorder (CMD) and suicidal ideation (SI) among JDs.

Method

Sampling strategy

Between February and April 2013, from a randomly selected sample of 42 942 Australian doctors, 12 252 doctors elected to complete the Beyond Blue National Mental Health Survey of Doctors and Medical Students (response rate of approximately 27%).19 Doctors were sampled according to their geographical location based on the Australian Standard Geographical Classification developed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), and correspondence was sent to the sample by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) on behalf of beyondblue. Doctors invited to participate in the survey were advised by mail of their upcoming receipt of a questionnaire in 2 weeks’ time, at which point a mail package was sent to all participants containing a hard copy questionnaire, an explanatory statement and a reply-paid envelope. Invitation letters accompanying the hard copy survey instrument included a URL for participants to access an online version of the survey instrument. Participants could choose to participate in the survey by completing the hard copy questionnaire and returning it via reply-paid envelope, or by completing the online questionnaire accessed through a secure URL. A reminder letter was sent after at least 2 weeks after receipt of the initial survey. Individual responses were not tracked and as such, all doctors received a reminder letter regardless of whether or not they had completed the survey already. Participation in the study was completely voluntary and anonymous, and participants were assured that their decision to participate would not affect their registration with AHPRA nor would the data collected be provided to AHPRA or the Medical Board of Australia.

While medical students and doctors at all levels were recruited as part of the overall survey, medical students, doctors who had completed training or were retired were excluded from this analysis. The population of interest for this study were full-time employed JDs, including interns, prevocational trainees and vocational trainees across all specialty training programmes. Full-time working hours was defined using the ABS standard classification of working 35 hours or more in a usual week.20 There were 3053 JDs in total, representing 24.9% of the overall sample. Of these, 2706 (88.6% of all JDs) were in full-time employment and used as the final sample in all subsequent analyses.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the design, recruitment or conduct of this study. Results will be disseminated via publication in an open access journal.

Variables of interest

Each participant was asked the average hours they worked per week in their current role. The two mental health outcomes of interest were presence of SI in the past year, assessed with a single item, ‘During the last 12 months have you had thoughts of taking your own life?’; and caseness for CMD assessed by the 28-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28).21 Using the binary scoring method (0-0-1-1),22 a cut-off of 4 on total GHQ-28 score was used as the threshold for CMD, which despite not yet being validated as an indicator of psychiatric disorder in medical professionals specifically, it has been shown to be comparable to clinician-delivered diagnostic assessments in the general population21 and has been successfully used in previous studies among physicians. Additional demographic variables measured were gender, age, location of primary place of work (metropolitan, rural/regional/remote), stage of training (intern, prevocational trainee, vocational trainee and career medical officer), whether they had received their medical degree overseas, marital status and area of specialty.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS software program (V.24). Logistic regression was used to model the associations between hours worked per week (entered as a continuous variable) and the mental health outcomes of CMD and SI. Interaction testing was used to examine for any effect modification from either gender or age group (up to 30 years of age compared with more than 30 years). The final adjusted models were adjusted for age, gender, stage of training, location of work, specialty, marital status and whether they had completed their medical degree overseas.

Results

Data were available for 2706 JDs, of whom the majority were female (58.5%; n=1583), aged between 26 and 40 years (72.1%; n=1951) and in a committed relationship (71.5%; n=1934). Most JDs worked in hospital settings (80.1%; n=2168) with a slight majority enrolled in a specialist or vocational training programme (58.9%; n=1594). 764 JDs (28.2%) completed their medical degree overseas. On average, JDs reported working a total of 50.1 hours per week (SD=13.4). A total of 952 JDs (36.4%) reported symptom levels indicating likely CMD and 12.3% (n=331) had experienced SI in the last 12 months.

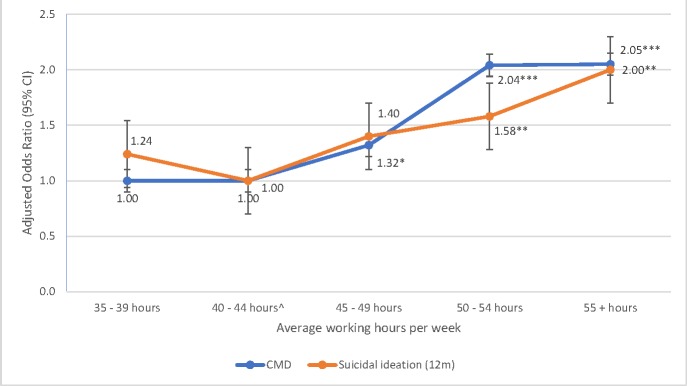

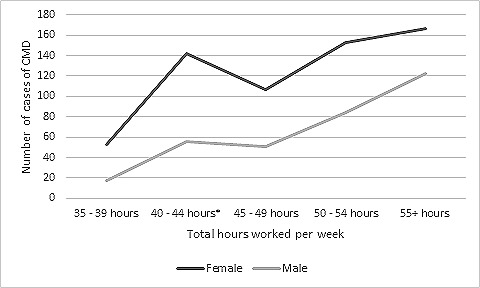

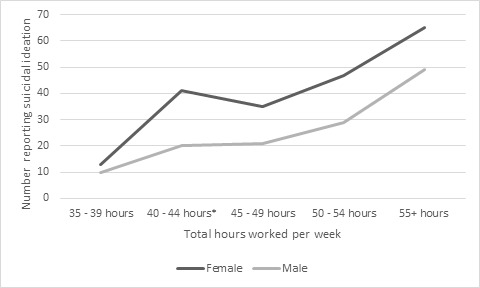

There was strong evidence of a positive relationship between the number of hours worked per week by JDs and both CMD (p<0.001) and SI (p<0.001). There was no evidence that these relationships differed by gender or age group (p>0.9 for CMD; p>0.5 for SI) as shown in figures 1–4. The associations between hours worked and both CMD and SI remained after adjustment for age, gender, training stage, location, area of specialty, marital status and whether the JD had trained overseas (p<0.001 for both) (table 1). The adjusted ORs for both CMD and SI according to different numbers of hours worked are shown in figure 5. Once a JD was working more than 50 hours per week, their odds of CMD was more than double and their odds of SI were increased by more than 50%. Among JDs working more than 55 hours per week, both the odds of CMD and SI were doubled.

Figure 1.

Caseness of common mental disorder (CMD) by average weekly working hours according to gender (n=2706) (interaction test comparing males and females, p>0.9).

Figure 2.

Presence of suicidal ideation in the past 12 months by average weekly working hours according to gender (n=2706) (interaction test comparing males and females, p>0.5).

Figure 3.

Caseness of common mental disorder (CMD) in the past 12 months by average weekly working hours according to age (n=2706) (interaction test comparing ≥30 years of age vs 31+ years of age, p>0.9).

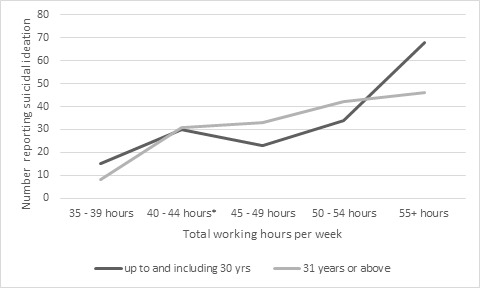

Figure 4.

Presence of suicidal ideation in the past 12 months by average weekly working hours according to age (n=2706) (interaction test comparing ≥30 years of age vs 31+ years of age, p>0.5).

Table 1.

Associations between average weekly working hours, CMD and suicidal ideation in JDs with unadjusted and adjusted estimates for effect size (95% CI) (n=2706)

| CMD (n=2706) | Suicidal ideation (n=2706) | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Unadjusted model | ||||

| Hours worked per week (continuous) | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.02) | <0.001 | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03) | <0.001 |

| Hours worked per week | ||||

| 35–39 hours | 0.95 (0.69 to 1.30) | 0.732 | 1.02 (.62 to 1.69) | 0.922 |

| 40–44 hours | Reference group | Reference group | ||

| 45–49 hours | 1.37 (1.06 to 1.77) | 0.014 | 1.51 (1.02 to 2.21) | 0.035 |

| 50–54 hours | 2.05 (1.62 to 2.59) | <0.001 | 1.77 (1.23 to 2.52) | 0.002 |

| 55+ hours | 2.05 (1.63 to 2.57) | <0.001 | 2.19 (1.57 to 3.05) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted model* | ||||

| Hours worked per week (continuous) | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.02) | <0.001 | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.02) | <0.001 |

| Hours worked per week | ||||

| 35–39 hours | 0.997 (0.72 to 1.38) | 0.984 | 1.24 (0.74 to 2.07) | 0.419 |

| 40–44 hours | Reference group | Reference group | ||

| 45–49 hours | 1.32 (1.02 to 1.70) | 0.037 | 1.40 (0.95 to 2.06) | 0.091 |

| 50–54 hours | 2.04 (1.60 to 2.59) | <0.001 | 1.58 (1.10 to 2.27) | 0.014 |

| 55+ hours | 2.05 (1.62 to 2.59) | <0.001 | 2.00 (1.42 to 2.81) | <0.001 |

*NB: analyses adjusted for age (continuous), gender, stage of training, location, area of specialty, marital status and whether medical degree was completed overseas. Reference group was 40–44 hours.

CMD, likely case of common mental disorder, assessed by the GHQ-28;SI, Positive response indicating suicidal ideation in the last year, assessed by a single item.

Figure 5.

Adjusted OR (95% CI) for common mental disorder (CMD) and suicidal ideation in junior doctors, by average hours worked per week (n=2076). CMD: likely case of common mental disorder, assessed by the GHQ-28. *NB: analyses adjusting for age (continuous), gender, stage of training, location, area of specialty, marital status and whether medical degree was completed overseas. Reference group was 40–44 hours.

Discussion

The results of this study support an association between long working hours and significantly higher likelihood of CMD and SI among JDs. Once JDs were working more than 55 hours a week, there was a doubling of risk for both CMD and SI. As a quarter (25.3%) of the sample reported working over 55 hours in an average week, these results suggest a considerable proportion of JDs may be at substantially increased risk of mental health problems and SI associated with longer working hours.

The main limitations of this study were its use of self-reported estimated working hours and cross-sectional data, the low response rate and that data was collected in 2013. Reported average hours worked are subject to recall bias, may deviate from actual hours worked and may not include unpaid hours, rostered and unrostered overtime, extra time on-call or proportion of night shifts across the week. However, an overall average of weekly hours provides a simple indicator of JDs’ current working hours that can be routinely assessed in a consistent, reliable manner. While the observed dose–response relationship adds weight to there being a direct link between working hours and poorer mental health indicators, the use of cross-sectional data precludes any conclusions about the temporal nature of the relationship and raises the prospect of reverse causation. Additionally, the study was not able to assess potential longer-term ‘lagged’ effects on mental health or examine effects of chronic or cumulative exposure to long workweeks or over time, although in general, the relationships between job stressors and mental health outcomes tends to be quite contemporaneous.23

While the threshold for ‘caseness’ on the GHQ-28 has not been validated as an indicator of psychiatric disorder in doctors, it has been widely validated in English and non-English speaking countries,24 in healthy workers25 and primary care samples, including an Australian community sample.26 The GHQ demonstrates good clinical validity in relation to diagnosed mental disorders, especially depression and anxiety27 28 and the threshold used in this study has demonstrated 100% specificity and over 80% sensitivity, providing the lowest rate of misclassification.29 The GHQ has been used in previous surveys of medical professionals but reaching caseness on this type of self-report scale is not the equivalent of a clinical diagnosis. Future studies should use diagnostic instruments to confirm present results. While the low response rate is a limitation, it is not unexpected, with response rates of a similar magnitude commonly seen in samples of doctors across a number of countries. However, the risk of response bias remains and may have had an impact on the associations reported in this study. Finally, the collection of data occurred in 2013 and as such, may not reflect the current working hours and regulatory situation. However, the average hours worked per week reported by this sample (50.1 hours) are very similar to the average of 52.5 total hours per week worked by doctors in 2016 reported by the Australian Medical Association’s national audit,30 suggesting that working patterns are broadly representative of those seen in the current context. To our knowledge, this was the largest and most recent national data available to date that examined the outcomes of interest to this particular study. We would also note that our main aim was to describe the relationship between working hours and mental health outcomes, not the prevalence of different working hours, and that such associations tend to be relatively stable over time.

Previous findings of general population working groups have demonstrated different types of relationships between health outcomes and increasing working hours, with some studies finding a U-shaped curve while others indicate no relationship until a certain tipping point or threshold is reached.1 31 32 It was for this reason that we modelled the relationship in a variety of different ways. Overall, our analysis suggest modelling a linear relationship seemed a reasonable, but not perfect, compromise, with increasing mental health problems at the number of hours worked increased. These results are consistent with some previous findings in physicians8 33 and the general population1 3 demonstrating an association between long weekly working hours and fatigue, reduced well-being and poor mental health. Our findings are also in line with longitudinal surveys that have demonstrated a relationship between adverse working conditions, including work arrangements and poorer self-rated health among Australian doctors.34 However, to the best of our knowledge this is the first time the relationship between working hours and these two important mental health outcomes has been defined in a group of JDs.

Previous international literature has acknowledged the complexity of doctors’ working environments, and the interplay between workplace variables and their levels of stress and mental well-being. While weekly working hours provide a simple quantitative measure of overall time at work, there are a number of issues that need to be considered in interpreting these findings, many of which are well noted by existing literature.35 36 Working hours and perceived stress, job demands and job satisfaction are related.37 For example, a stressed doctor may remain at work longer because they are less efficient and need more time to complete tasks, or may perceive that this is needed. The role of psychosocial factors in employee well-being38 and doctors stress levels is clearly established, and so needs to be addressed alongside working hours to ensure that these hours are spent in a supportive environment conducive to mental well-being. Family responsibilities, conflict and imbalance between work and home life, and stress associated with this both within and outside the work environment may be caused by long working hours, or may result in long work hours, and these relationships cannot be explicated with a measure of weekly hours. Related factors such as sleep and fatigue have also been associated with compromised mental health in general population and doctors,39–41 and may be potential confounders not assessed by this study.42 43

The results of this study provide clear evidence of a strong association between poor mental health outcomes and working 50 or more hours a week among JDs, suggesting that there may be mental health risks associated with excessive working hours in this group. Doctors’ mental health is a complex, multicausal issue shaped by individual, workplace, and organisational level factors, including broader systemic issues such as regulatory practices, meaning hours worked are likely to be only one of a range of workplace factors likely to play a role in JDs’ mental health.44 However, working hours are a modifiable workplace risk factor that needs to be addressed as one part of multilevel interventions, where individual, team and organisational-level strategies are implemented in tandem. This is in line with recent literature that recognises the importance of providing both individual and organisational or structural solutions to create a mentally healthy workplace.45 46

However, caution is needed in how health systems respond to this finding to ensure a considered multilevel approach is taken by organisations and policy makers. Simply putting in place legislation to restrict JDs’ working hours may not be effective in attenuating this risk, particularly if such interventions result in increased workload during shifts or simply lead to an increase in unpaid, unrostered overtime. The potential for organisational-level interventions in a healthcare context has been highlighted by previous reviews of controlled interventions to reduce burnout among physicians47 48 and healthcare workers,49 which suggested that rescheduling of work hours, reducing workloads and modifying local working conditions can lead to modest reductions in burnout and work-related stress. Efforts to address rostering need to be delivered alongside strategies that address team dynamics and workplace efficiency,50 so that a reduction in working hours does not occur at the expense of the quality of JDs’ training and supportive work environment. Ideally, the optimal solution would include increasing the efficiency of the work environment to reduce the workload of JDs, implementing kinder rostering and work practices as well as ensuring adequate staffing to reduce total hours per JD.

Future studies will need to consider other factors in addition to the actual number of hours worked, such as the workload over this time and the related issues of time pressure, work-life conflict, shift work and roster scheduling, and sleep deprivation. Workplaces could investigate measures to improve workplace efficiency within healthy working hours such as appropriate clinical task allocation within teams (eg, encourage nurses and clerks to do non-doctor required tasks). Importantly, such measures should be implemented with appropriate attention to resourcing of the healthcare system and the need to maintain high-quality patient care and safety. These findings indicate that management of working hours are likely to represent an important strategy to help improve JDs’ mental health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Beyond Blue, the Project Advisory Group and members of the research team for their contribution in undertaking the initial 2013 ‘National Mental Health Survey of Doctors and Medical Students’ survey. We also acknowledge the involvement of the doctors and medical students who participated in the survey.

Footnotes

Twitter: @jessiemaed, @venessb, @Samuel_Harvey

Contributors: SBH and KP designed the study, planned and undertook statistical analysis and interpretation. KP drafted and finalised the manuscript with review by SBH. JC, ADL, AM, JD, BGV and HC reviewed, commented on and approved the final manuscript. SBH is guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. SBH and KP had full access to the data.

Funding: This work was supported by the Health Workforce Programme, Commonwealth Department of Health, Australian Government, iCare Foundation and NSW Health. Beyond Blue, an Australian mental health charity, conducted the initial survey of doctors’ mental health in 2013. KP is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The recruitment and data collection in this study was approved by Monash University Human Research Ethics Office and Committee. This study has been approved by University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Office (HC190896).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1.Bannai A, Tamakoshi A. The association between long working hours and health: a systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Scand J Work Environ Health 2014;40:5–18. 10.5271/sjweh.3388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Virtanen M, Stansfeld SA, Fuhrer R, et al. Overtime work as a predictor of major depressive episode: a 5-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. PLoS One 2012;7:e30719 10.1371/journal.pone.0030719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virtanen M, Ferrie JE, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Long working hours and symptoms of anxiety and depression: a 5-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Psychol Med 2011;41:2485–94. 10.1017/S0033291711000171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watanabe K, Imamura K, Kawakami N. Working hours and the onset of depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med 2016;73:877–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Jareño MC, Demou E, Vargas-Prada S, et al. European working time directive and doctors' health: a systematic review of the available epidemiological evidence. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004916 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shields M. Long working hours and health. Health Reports-Statistics Canada 1999;11:33–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tyssen R, Vaglum P, Grønvold NT, et al. The impact of job stress and working conditions on mental health problems among junior house officers. A nationwide Norwegian prospective cohort study. Med Educ 2000;34:374–84. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00540.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tyssen R, Vaglum P. Mental health problems among young doctors: an updated review of prospective studies. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2002;10:154–65. 10.1080/10673220216218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Temple J. Resident duty hours around the globe: where are we now? BMC Med Educ 2014;14:S8 10.1186/1472-6920-14-S1-S8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cairns H, Hendry B, Leather A, et al. Outcomes of the European working time directive. British Medical Journal Publishing Group 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Philibert I, Friedmann P, Williams WT. New requirements for resident duty hours. JAMA 2002;288:1112–4. 10.1001/jama.288.9.1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutter MM, Kellogg KC, Ferguson CM, et al. The impact of the 80-hour resident workweek on surgical residents and attending surgeons. Ann Surg 2006;243:864–75. 10.1097/01.sla.0000220042.48310.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gough IR. The impact of reduced working hours on surgical training in Australia and New Zealand. The Surgeon 2011;9:S8–9. 10.1016/j.surge.2010.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glasgow NJ, Bonning M, Mitchell R. Perspectives on the working hours of Australian junior doctors. BMC Med Educ 2014;14:S13 10.1186/1472-6920-14-S1-S13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Grady G, Harper S, Loveday B, et al. Appropriate working hours for surgical training according to Australasian trainees. ANZ J Surg 2012;82:225–9. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2011.05992.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AMA National Code of Practice - Hours of Work, Shiftwork and Rostering for Hospital Doctors. ACT: Australian Medical Association, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munir V. MABEL: doctors shouldn’t work in excess of 50 hours per week. InSight 2018;6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Grady G, Loveday B, Harper S, et al. Working hours and roster structures of surgical trainees in Australia and New Zealand. ANZ J Surg 2010;80:890–5. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05528.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MI W, Hafekost K, Lawrence D. National mental health survey of doctors and medical students. Beyond Blue 2013. [Epub ahead of print: 24 Sep 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 20.ABo S. Cat no 6202.0 - Labour Force, Australia, Jul 2017. Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017.

- 21.Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, et al. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the who study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med 1997;27:191–7. 10.1017/S0033291796004242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldberg D, Williams P. A user’s guide to the GHQ. Windsor: NFER-Nelson, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milner A, Aitken Z, Kavanagh A, et al. Persistent and contemporaneous effects of job stressors on mental health: a study testing multiple analytic approaches across 13 waves of annually collected cohort data. Occup Environ Med 2016;73:787–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vieweg BW, Hedlund JL. The general health questionnaire (GHQ): a comprehensive review. J Operation Psychiat 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwata N, Saito K. The factor structure of the 28-item general health questionnaire when used in Japanese early adolescents and adult employees: age- and cross-cultural comparisons. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992;242:172–8. 10.1007/BF02191565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tennant C. The general health questionnaire: a valid index of psychological impairment in Australian populations. Med J Aust 1977;2:392–4. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1977.tb114568.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the general health questionnaire. Psychol Med 1979;9:139–45. 10.1017/S0033291700021644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg DP, Rickels K, Downing R, et al. A comparison of two psychiatric screening tests. Br J Psychiatry 1976;129:61–7. 10.1192/bjp.129.1.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banks MH. Validation of the general health questionnaire in a young community sample. Psychol Med 1983;13:349–53. 10.1017/S0033291700050972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Assocation AM 2016 AMA safe hours audit: managing the risks of fatigue in the medical workforce. AMA 2017. (15 July 2017).

- 31.Härmä M. Workhours in relation to work stress, recovery and health. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006;32:502–14. 10.5271/sjweh.1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sparks K, Cooper C, Fried Y, et al. The effects of hours of work on health: a meta-analytic review. J Occup Organ Psychol 1997;70:391–408. 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00656.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tucker P, Brown M, Dahlgren A, et al. The impact of junior doctors’ worktime arrangements on their fatigue and well-being. Scand J Work Environ Health 2010;36:458–65. 10.5271/sjweh.2985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milner A, Witt K, Spittal MJ, et al. The relationship between working conditions and self-rated health among medical doctors: evidence from seven waves of the medicine in Australia balancing employment and life (MABEL) survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:609 10.1186/s12913-017-2554-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Firth-Cozens J. Doctors, their wellbeing, and their stress: it's time to be proactive about stress—and prevent it. BMJ 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Firth-Cozens J, Moss F. Hours, sleep, teamwork, and stress: sleep and teamwork matter as much as hours in reducing doctors' stress. British Medical Journal Publishing Group 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mache S, Vitzthum K, Klapp BF, et al. Stress, health and satisfaction of Australian and German doctors--a comparative study. World Hosp Health Serv 2012;48:21–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Netterstrøm B, Conrad N, Bech P, et al. The relation between work-related psychosocial factors and the development of depression. Epidemiol Rev 2008;30:118–32. 10.1093/epirev/mxn004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Afonso P, Fonseca M, Pires JF. Impact of working hours on sleep and mental health. Occup Med 2017;67:377–82. 10.1093/occmed/kqx054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leonard C, Fanning N, Attwood J, et al. The effect of fatigue, sleep deprivation and onerous working hours on the physical and mental wellbeing of PRE-REGISTRATION house officers. Ir J Med Sci 1998;167:22–5. 10.1007/BF02937548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mansukhani MP, Kolla BP, Surani S, et al. Sleep deprivation in resident physicians, work hour limitations, and related outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Postgrad Med 2012;124:241–9. 10.3810/pgm.2012.07.2583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tyssen R, Vaglum P, Grønvold NT, et al. The relative importance of individual and organizational factors for the prevention of job stress during internship: a nationwide and prospective study. Med Teach 2005;27:726–31. 10.1080/01421590500314561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Hulst M. Long workhours and health. Scand J Work Environ Health 2003;29:171–88. 10.5271/sjweh.720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harvey SB, Modini M, Joyce S, et al. Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occup Environ Med 2017;74:301–10. 10.1136/oemed-2016-104015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joyce S, Modini M, Christensen H, et al. Workplace interventions for common mental disorders: a systematic meta-review. Psychol Med 2016;46:683–97. 10.1017/S0033291715002408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petrie K, Joyce S, Tan L, et al. A framework to create more mentally healthy workplaces: a viewpoint. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2018;52:15–23. 10.1177/0004867417726174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murray M, Murray L, Donnelly M. Systematic review of interventions to improve the psychological well-being of general practitioners. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:36 10.1186/s12875-016-0431-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA internal medicine 2017;177:195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruotsalainen JH, Verbeek JH, Mariné A, et al. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014;11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH, Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Elsevier, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.