Sir,

Staphylococcus aureus is a common bacterial pathogen of human beings. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) could be community acquired or health care acquired (CA-MRSA or HA-MRSA). CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA show different genetic, phenotypic, epidemiological, and clinical characteristics.[1] The resistance is due to mutation in mecA gene, which is located in a region called the Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec). While CA-MRSA carries either SCCmec IV or V, the HA-MRSA have SCCmec I, II, or III. Panton–valentine leukocidin (PVL) is a cytotoxin produced by S. aureus. The significance of PVL in virulence of CA-MRSA is well established, especially in skin and soft tissue infections.[2] Of late, there has been a worldwide increase in the PVL harboring S. aureus clinical isolates. Further, there are increasing reports of CA-MRSA being isolated from health-care settings and HA-MRSA circulating in the community. Saudi Arabia has seen a hike in the number of MRSA infections in recent years.[3] We undertook this study to estimate the prevalence of PVL among MRSA clinical isolates in Al-Ahsa city of Saudi Arabia and to determine PVL distribution among HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA.

Seventy-two consecutive, non-repetitive MRSA isolates from King Fahad Hospital, Al-Ahsa, and King Faisal University Health Centre were analyzed. Isolates were labeled as CA-MRSA or HA-MRSA based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria. Standard bacterial identification methods and phenotypic determination of methicillin resistance by cefoxitin susceptibility testing were performed. A duplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was done with two primer sets (mecA and PVL).[4]

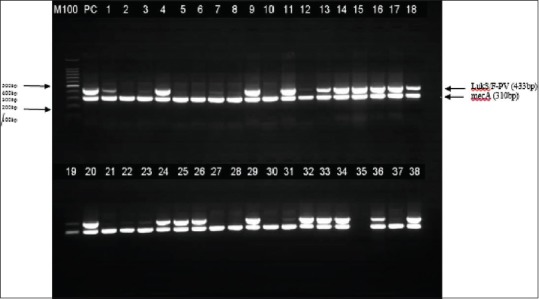

Cefoxitin disc diffusion test and PCR confirmed 71 isolates as MRSA [Figure 1]. Forty (56.3%) were identified as CA-MRSA and the remaining as HA-MRSA (30/71, 43.7%). PVL gene was detected among 27/40 (67.5%) and 9/31 (29%) of CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA strains, respectively.

Figure 1.

Gel electrophoresis photograph of duplex polymerase chain reaction

Studies from other Arabian Gulf countries have demonstrated CA-MRSA infections in health-care institutions. There seems to be a shift in the epidemiology of MRSA as some CA-MRSA clonal types are increasingly reported causing health-care-acquired infections.[5] We assume that a good proportion of PVL-positive HA-MRSA in our study could be either SCCmec type I–III or SCCmec types IV or V attributed as CA-MRSA hitherto, but increasingly reported from health-care institutions.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that a considerable number of MRSA identified as hospital acquired also possessed PVL gene, highlighting the significance of changing epidemiology of MRSA. Further studies need to be done for complete molecular characterization of MRSA including SCCmec genotype, clonal complexes, and multi-locus strain typing.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Mr. Hani Al-Rasasi and Mr. Hani Al-Farhan, Division of Microbiology, College of Medicine, KFU, Al-Ahsa, KSA, for their contributions in the technical support and assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.David MZ, Daum RS. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:616–87. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shallcross LJ, Fragaszy E, Johnson AM, Hayward AC. The role of the Panton-Valentine leucocidin toxin in Staphylococcal disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:43–54. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70238-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bukharie HA. A review of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus for primary care physicians. J Family Community Med. 2010;17:117–20. doi: 10.4103/1319-1683.74320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClure JA, Conly JM, Lau V, Elsayed S, Louie T, Hutchins W, et al. Novel multiplex PCR assay for detection of the staphylococcal virulence marker Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes and simultaneous discrimination of methicillin-susceptible from -resistant staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1141–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.1141-1144.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kale P, Dhawan B. The changing face of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2016;34:275–85. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.188313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]