Abstract

Background

Research on clinical application of oral naltrexone agrees on several things. From a pharmacological perspective, naltrexone works. From an applied perspective, the medication compliance and the retention rates are poor.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of naltrexone maintenance treatment versus placebo or other treatments in preventing relapse in opioid addicts after detoxification.

Search methods

We searched: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL ‐ The Cochrane Library issue 6 2010), PubMed (1973‐ June 2010), CINAHL (1982‐ June 2010). We inspected reference lists of relevant articles and contacted pharmaceutical producers of naltrexone, authors and other Cochrane review groups.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled clinical trials which focus on the use of naltrexone maintenance treatment versus placebo, or other treatments to reach sustained abstinence from opiate drugs

Data collection and analysis

Three reviewers independently assessed studies for inclusion and extracted data. One reviewer carried out the qualitative assessments of the methodology of eligible studies using validated checklists.

Main results

Thirteen studies, 1158 participants, met the criteria for inclusion in this review.

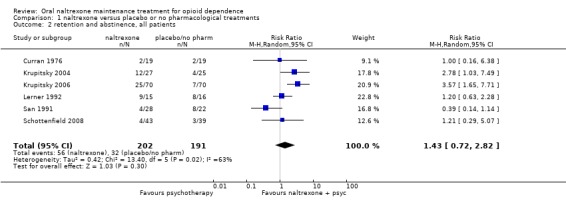

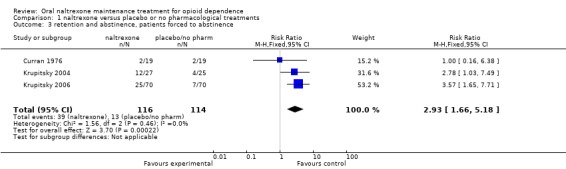

Comparing naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatments, no statistically significant difference were noted for all the primary outcomes considered. The only outcome statistically significant in favour of naltrexone is re incarceration, RR 0.47 (95%CI 0.26‐0.84), but results come only from two studies. Considering only studies were patients were forced to adherence a statistical significant difference in favour of naltrexone was found for retention and abstinence, RR 2.93 (95%CI 1.66‐5.18).

Comparing naltrexone versus psychotherapy, in the two considered outcomes, no statistically significant difference was found in the single study considered.

Naltrexone was not superior to benzodiazepines and to buprenorphine for retention and abstinence and side effects. Results come from single studies.

Authors' conclusions

The findings of this review suggest that oral naltrexone did not perform better than treatment with placebo or no pharmacological agent with respect to the number of participants re‐incarcerated during the study period. If oral naltrexone is compared with other pharmacological treatments such as benzodiazepine and buprenorphine, no statistically significant difference was found. The percentage of people retained in treatment in the included studies is however low (28%). The conclusion of this review is that the studies conducted have not allowed an adequate evaluation of oral naltrexone treatment in the field of opioid dependence. Consequently, maintenance therapy with naltrexone cannot yet be considered a treatment which has been scientifically proved to be superior to other kinds of treatment.

Plain language summary

Oral naltrexone as maintenance treatment to prevent relapse in opioid addicts who have undergone detoxification

Opioid dependence is considered to be a lifelong, chronic relapsing disorder. Substantial therapeutic efforts are needed to keep people drug free. Methadone treatment plays a vital role in detoxification or maintenance programs but some individuals who are on methadone continue to use illicit drugs, commit crime and engage in behaviours that promote the spread of communicable diseases. Naltrexone is a long acting opioid antagonist that does not produce euphoria and is not addicting. It is used in accidental heroin overdose and for the treatment of people who have opioid dependence. Naltrexone is particularly suitable to prevent a relapse to opioid use after heroin detoxification for those for whom failure to comply with treatment has major consequences, for example health professionals, business executives and individuals under legal supervision. Medication compliance and retention rates with naltrexone treatment are however low. In this review of the medical literature oral naltrexone, with or without psychotherapy, was no better than placebo or no pharmacological treatments with regard to retention in treatment, use of the primary substance of abuse or side effects. The only outcome that was clearly in favour of naltrexone was a reduction of re incarcerations by about a half but these results were from only two studies. In single studies naltrexone was not superior to benzodiazepines or buprenorphine for retention, abstinence or side effects. The review authors identified a total of 13 randomised controlled studies that involved 1158 opioid addicts treated as outpatients following detoxification. Less than a third of participants were retained in treatment over the duration of the included studies. The mean duration was six months (range one to 10 months). None of included studies considered deaths from fatal overdoses in people treated with naltrexone.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatments for opioid dependence.

| naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatments for opioid dependence | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with opioid dependence Settings: Intervention: naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatments | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatments | |||||

| retention and abstinence, all patients | Study population | RR 1.43 (0.72 to 2.82) | 393 (6 studies) | |||

| 168 per 1000 | 240 per 1000 (121 to 474) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 133 per 1000 | 190 per 1000 (96 to 375) | |||||

| abstinence at follow up | Study population | RR 1.28 (0.8 to 2.05) | 116 (3 studies) | |||

| 340 per 1000 | 435 per 1000 (272 to 697) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 364 per 1000 | 466 per 1000 (291 to 746) | |||||

| side effects | Study population | RR 1.29 (0.54 to 3.11) | 159 (4 studies) | |||

| 270 per 1000 | 348 per 1000 (146 to 840) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 360 per 1000 | 464 per 1000 (194 to 1000) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Background

Description of the condition

Opioid dependence is considered a chronic lifelong relapsing disorder, which requires substantial therapeutic efforts to keep patients drug free (Mc Lellan 2000). Estimates of the prevalence of problem opioid use in European countries during the period 2002–07 range roughly between one and six cases per 1 000 population aged 15–64; overall prevalence of problem drug use is estimated to range from under three cases to 10 cases per 1 000. The average prevalence of problem opioid use in the countries providing data is estimated to be between 3.6 and 4.6 cases per 1 000 of the population aged 15–64. Assuming that this reflects the EU as a whole, it implies some 1.4 million (1.2–1.5 million) problem opioid users in the EU and Norway in 2007 (EMCDDA 2009). In Australia the prevalence of heroin users in years 2007‐2008 has been estimated of 1.6 per 1000 (AIHW 2009). In US, of the 7.0 million persons aged 12 or older classified with dependence on or abuse of illicit drugs in 2008, 1.7 million persons were classified with dependence on or abuse of opioid (SAMHSA 2009). The introduction of methadone in the 1960's dramatically changed the course of opiate dependence treatment. The rationale of this treatment (aimed at detoxification or at maintenance) is simple and the research evidence to support the value of methadone is overwhelming. Reviews confirms that methadone treatment plays a vitally important role in reducing morbidity and mortality associated with heroin use (Amato 2005; Clark 2002; Faggiano 2003; Mattick 2008; Mattick 2009) Although methadone produces the cited benefits, it is far from being a perfect medication. It is true that some individuals being treated with methadone continue to use illicit drugs, commit crime and engage in behaviours that promote the spread of communicable diseases (Rawson 2000).

Description of the intervention

Naltrexone is a long‐acting, non‐selective opioid‐antagonist with highest affinity to mu‐opioid receptors (Preston 1993), used for the treatment of opioid dependence to prevent a relapse to opioid use after heroin detoxification and to treat accidental heroin overdose. During the 1970's it was hoped that naltrexone would be widely used as a heroin addiction treatment since it is non‐addicting and produce no euphoria. It is a pure mu opioid receptor antagonist that provides a complete 24 to 72 hour (depending on dose) blockade of all opiate effects (Rawson 2000).

How the intervention might work

Oral naltrexone is approved for relapse prevention of alcohol and opioid dependence in several countries. A daily ingested dose of 50 mg sufficiently blocks the effect of opioids to prevent relapse.The clinical research and the clinical application of naltrexone over the past two decades have had consistent findings. From a pharmacological perspective, the naltrexone has good pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties. O'Connor 2000 stated that naltrexone has low retention rates and no efficacy on reducing opioid use compared with placebo. Ward 1999 concluded that naltrexone has only been effective in opioid dependence for whom failure to comply with treatment has major consequences. Although there are selected patient groups who may be good candidates for naltrexone treatment e.g. health professionals (Ling 1984), business executives (Washton 1984) and individuals under legal supervision (Brahen 1984), in general the compliance rates with naltrexone treatment are very poor.

Why it is important to do this review

The review is a substantial update of a previous review published in 2005. Due the improving clinical interest in this medication, the review is aimed to offer comprehensive, updated information on the available evidence on the use of oral naltrexone in opoid dependent people.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of maintenance treatment with oral naltrexone versus placebo, other pharmacological or psychosocial treatments in preventing relapse in opioid addicts after detoxification, retention in treatment, and criminal activity.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials on oral naltrexone treatment for opioid dependence. Cross‐over studies have been excluded.

Types of participants

All in‐patients and out‐patients dependent on heroin, or former heroin addicts dependent on methadone and participating in a naltrexone treatment programme are considered. No distinction is made between addicts dependent on heroin alone or on multiple drugs.

Types of interventions

Experimental Interventions: Treatment with oral naltrexone in any dosage after detoxification alone or in combination with psychosocial treatments Control intervention: placebo no intervention other pharmacological treatments psychosocial treatments

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Abstibence in using heroin measured by:

number of participants retained at the end of the study or

number of participants retained and abstinent at the end of the study or

number of participants without positive urinalysis at the end of the study and self report data

2. Relapse at follow up measured as number of participants relapsed at the end of follow u

3. Mortality

Secondary outcomes

4. Side effects measured as number of participants with at least one side effect 5. Criminal activity measured as number of participants re‐incarcerated during the treatment

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Electronic searches

Relevant trials from the last search were obtained from the following sources:

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL‐ The Cochrane Library, issue 6, 2010) which include the Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Groups specialised register

PubMed (1973‐June 2010)

CINAHL (1982‐ June 2010)

Databases were searched using a strategy developed incorporating the filter for the identification of RCTs (Higgins 2008) combined with selected MeSH terms and free text terms relating to cocaine dependence. The search strategy for PubMed is shown in Appendix 1. A similar search strategy was used for the Cochrane Library and CINAHL.

We also searched for ongoing clinical trials and unpublished studies via Internet searches on the following sites:

http://www.controlled‐trials.com

http://clinicalstudyresults.org

http://centerwatch.com

osservatorio nazionale sulla sperimentazione clinica dei medicinali ‐ https://oss‐sper‐clin.agenziafarmaco.it

Searching other resources

Searching other resources:

We also searched:

references of the articles obtained by any means were searched

conference proceedings likely to contain trials relevant to the review

contact investigators, relevant trial authors seeking information about unpublished or incomplete trials.

All searches included non‐English language literature and studies with English abstracts were assessed for inclusion. When considered likely to meet inclusion criteria, studies were translated.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three reviewer (SM, LA, SV) inspected the search hits by reading titles and abstracts. Each potentially relevant study located in the search were obtained in full text and assessed for inclusion independently by two reviewers (SM, LA). Doubts were solved by discussion between the authors.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers (SM, LA). Any disagreements were discussed and solved by consensus

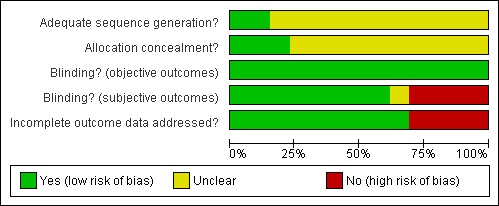

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias assessment for RCTs and CCTs in this review were performed using the 5 criteria recommended by the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2008). The recommended approach for assessing risk of bias in studies included in Cochrane Review is a two‐part tool, addressing five specific domains (namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, and other issues). The first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement relating to the risk of bias for that entry. This is achieved by answering a pre‐specified question about the adequacy of the study in relation to the entry, such that a judgement of "Yes" indicates low risk of bias, "No" indicates high risk of bias, and "Unclear" indicates unclear or unknown risk of bias. To make these judgments we used the criteria indicated by the handbook adapted to the addiction field. See Appendix 2 for details.

The domains of sequence generation and allocation concealment (avoidance of selection bias) were addressed in the tool by a single entry for each study.

Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessor (avoidance of performance bias and detection bias) were considered separately for objective outcomes (e.g. drop out, use of substance of abuse measured by urine‐analysis, subjects relapsed at the end of follow up, subjects engaged in further treatments) and subjective outcomes (e.g. duration and severity of signs and symptoms of withdrawal, patient self‐reported use of substance, side effects, social functioning as integration at school or at work, family relationship, ).

Incomplete outcome data (avoidance of attrition bias) were considered for all outcomes except for the drop out from the treatment, which is very often the primary outcome measure in trials on addiction. It was assessed separately for results at the end of the study period and for results at follow up.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous outcomes were analysed by calculating the relative risk (RR) for each trial, with the uncertainty in each result expressed with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Continuous outcomes were analysed by calculating the weighted mean difference (MD) or the standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95%CI. For outcomes assessed by scales we compared and pool the mean score differences from the end of treatment to baseline (post minus pre) in the experimental and control group. In case of missing data about the standard deviation of the change we imputed this measure using the standard deviation at the end of treatment for each group.

Unit of analysis issues

We didn't use data presented as number of positive urine tests over total number of tests in the experimental and control group as a measure of substance abuse. This is because using the number of tests instead of the number of participants as the unit of analysis violates the hypothesis of independence among observations. In fact, the results of tests done in each participant are not independent.

If all arms in a multi‐arm trial are to be included in the meta‐analysis and one treatment arm is to be included in more than one of the treatment comparisons, then we divided the number of events and the number of participants in that arm by the number of treatment comparisons made. This method avoid the multiple use of participants in the pooled estimate of treatment effect while retaining information from each arm of the trial. It compromises the precision of the pooled estimate slightly.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Statistically significant heterogeneity among primary outcome studies was assessed with Chi‐squared (Q) test and I‐squared (Higgins 2008). A significant Q ( P<.05) and I‐squared of at least 50% was considered as statistical heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We used funnel plots (plots of the effect estimate from each study against the sample size or effect standard error) to assess the potential for bias related to the size of the trials, which could indicate possible publication bias

Data synthesis

The outcome measures from the individual trials were combined through meta‐analysis where possible (clinical comparability of intervention and outcomes between trials) using a fixed‐effect model unless there is significant statistical heterogeneity, in which case a random‐effects model was used.

Sensitivity analysis

To incorporating assessment in the review process we first plotted intervention effects estimates for different outcomes stratified for risk. If differences in results were presents among studies at different risk of bias, we then performed sensitivity analysis excluding from the analysis studies with high risk of bias. We also performed subgroup analysis for studies with low and unclear risk of bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

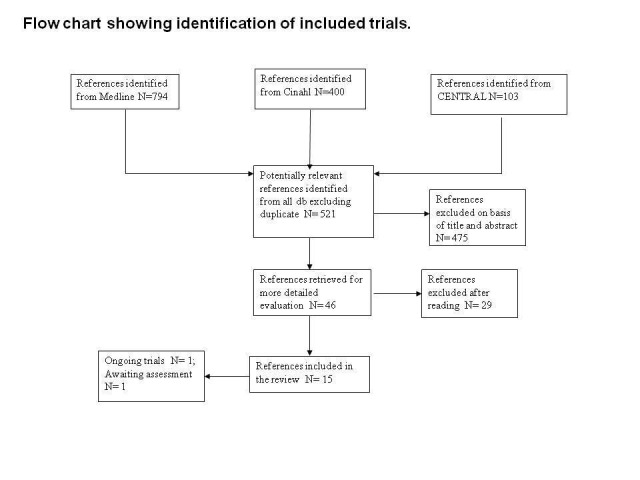

With the bibliographic searches 521 unique references were identified . After inspection of titles and abstracts 46 articles were judges potentially relevant. and were acquired in full text for more detailed evaluation. 30 studies were excluded, 13 included, one was ongoing study and one published in Russian was classified as study awaiting classification, see Figure 1 For substantive descriptions of studies seeCharacteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

1.

Flow chart showing identification of included studies

Included studies

Included studies 13 studies with 1158 participants meet the inclusion criteria for this review.

Duration of trials: mean duration: six months (range 1 to 10 months)

Treatment regimes and setting: The countries in which the studies were conducted were the following: USA: four studies, Israel: two studies, Russia two studies, Italy, Spain, China, Malaysia and German one study each. The naltrexone dosage varied between the studies: three times weekly application: four studies (100‐100‐150 mg three studies and 50‐50‐50 one study): ; twice weekly application (100‐ 150 mg): two studies; 50 mg every day: four studies; six days application but the dose is not specified: one study; 100 mg for five days and 150 mg on Saturday: one study and one study do not specify the doses and the frequency of administration. One study (Krupitsky 2006) added also fluoxitine 20 mg/day or fluoxetine placebo, one study added also prazepam (1 mg/twice daily) or prazepam placebo ( Stella 2005). It should be noted that in the two Russian studies (Krupitsky 2004, Krupitsky 2006) agonist maintenance was not allowed, patients were living with family members, and had a family member who supervised adherence .

All trials were conducted on outpatients basis. Participants: 1158 opiate addicts after detoxification: Three studies included only male participants (Hollister 1978; Rawson 1979; Shufman 1994). Three studies did not give the information on the gender of the participants (Curran 1976; Lerner 1992, Stella 2005). In the other five studies the percentage of male ranged from 72% to 90. Mean age ranged from 22 and 39 years. In Cornish 1977 and in Curran 1976 participants were all probationers or parolees with previous history of incarcerations.

Comparisons:

Naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatment, 13 studies, 891 participants. This comparison includes four studies, 329 participants that compared naltrexone versus placebo (Curran 1976; Guo 2001; Hollister 1978; San 1991), five studies, 337 participants, that compared naltrexone plus psychotherapy versus placebo plus psychotherapy (Krupitsky 2004;Krupitsky 2006; Lerner 1992; Schottenfield 2008; Shufman 1994) and four studies, 225 participants that compared naltrexone plus psychotherapy versus psychotherapy (Cornish 1977; Rawson 1979; Stella 2005; Ladewig 1990). A subgroup analysis was also performed for studies where participants were involved in special procedures or cultural situations to foster adherence : . paroless or probationers (Cornish 1977, Curran 1976) and studies conducted in Russia where agonist maintenance was not allowed, patients were living with family members, and had a family member who supervised adherence (Krupitsky 2004,Krupitsky 2006).

Naltrexone versus psychotherapy: one study, 58 participants ( Rawson 1979).

Naltrexone + psychosocial therapy vs benzodiazepines + psychosocial therapy: one study, 140 participants (Krupitsky 2006)

Naltrexone + psychosocial therapy vs buprenorphine + psychosocial therapy : one study, 87 participants (Schottenfield 2008

Excluded studies

Thirty one studies did not meet the criteria for inclusion in this review. The grounds for exclusion were: study design not in the inclusion criteria: 17; type of intervention not in the inclusion criteria: 11; study design and outcomes not in the inclusion criteria: two; not possible to extract the data: one.

Risk of bias in included studies

All included studies were randomised controlled trial.

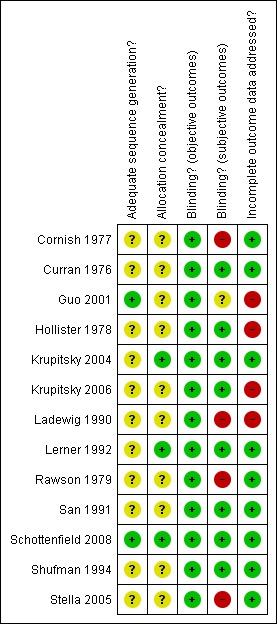

Allocation

Sequence generation: sequence generation was adequate in two studies ( Guo 2001; Schottenfield 2008); it was unclear in all the other studies

Allocation concealment: : allocation concealment was judged as adequate in three studies ( Krupitsky 2004; Lerner 1992;Schottenfield 2008); it was unclear in all the other studies

Blinding

Eight studies were double blind (Curran 1976; Hollister 1978; Krupitsky 2004; Krupitsky 2006; Lerner 1992; San 1991; Schottenfield 2008; Shufman 1994); Blinding was judged as adequate in these trials for subjective outcomes: Blinding was judged unclear in one study ( Guo 2001); the other studies were open label and they were judged as high risk of bias for subjective outcomes

Incomplete outcome data

Incomplete outcome data was correctly addressed in nine studies (Cornish 1977; Curran 1976; Krupitsky 2004; Lerner 1992; Rawson 1979; San 1991; Schottenfield 2008; Shufman 1994; Stella 2005) ; they other studies was judges as a high risk of bias for this items.

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for see the assessment of risk of bias in the included studies.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We could not include the study of Hollister 1978 in the meta‐analysis because the authors did not specify the number of participants allocated to each group. They report that seven participants in the naltrexone group and six participants in the placebo group stayed in treatment until the end of study (retention in treatment). Then they report that 39 out of 60 participants in the naltrexone group and 38 out of 64 participants in the placebo group had no positive urine samples, but they do not specify when they measured these outcomes during the study. Moreover they report these results only for the 65% of participants randomised.

Comparison 1. Naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatment

See Table 1

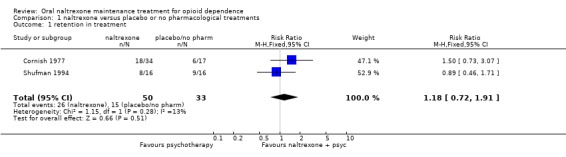

1.1 Retention in treatment two studies (Cornish 1977;Shufman 1994), 88 participants, RR 1.18 (95%CI 0.72‐1.91) no statistically significant difference seeAnalysis 1.1 In Cornish 1977, where participants were probationers or paroles, retention was in favour of naltrexone treatment, even if the difference was not statistically significant: RR 1.50 (CI95% 0.73‐ 3.07)

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatments, Outcome 1 retention in treatment.

1.2 Retention and abstinence

six studies (Curran 1976; Krupitsky 2004; Krupitsky 2006; Lerner 1992; San 1991; Schottenfield 2008), 393 participants, RR 1.43 [0.72, 2.82] no statistically significant difference, seeAnalysis 1.2 Subgroup analysis of studies where patients were forced to adherence (Curran 1976, Krupitsky 2004, Krupitsky 2006) showed a satistically significant difference in favour of naltrexone : 230 participants, RR 2.93 (CI95% 1.66‐5.18) See Analysis 1.3

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatments, Outcome 2 retention and abstinence, all patients.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatments, Outcome 3 retention and abstinence, patients forced to abstinence.

1.3 Abstinence

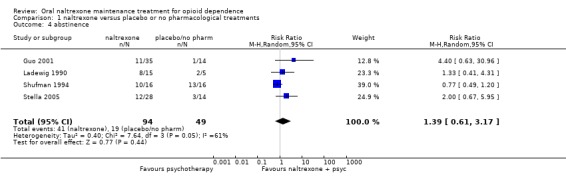

four studies (Guo 2001; Ladewig 1990; Shufman 1994; Stella 2005) 143 participants, RR 1.39 (95%CI 0.61‐3.17), no statistically significant difference seeAnalysis 1.4, due to the high heterogeneity (P=0.05), we applied random effect model seeAnalysis 1.4

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatments, Outcome 4 abstinence.

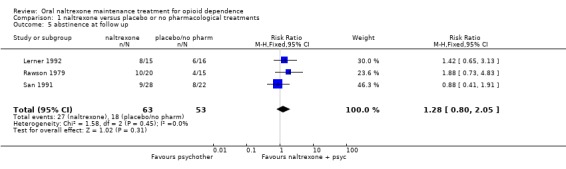

1.4 Abstinence at follow up

three studies ( Lerner 1992; Rawson 1979; San 1991), 116 participants, RR 1.28 (95%CI 0.80‐2.08) no statistically significant difference seeAnalysis 1.5

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatments, Outcome 5 abstinence at follow up.

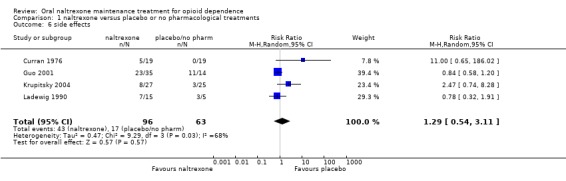

1.5 Side effects

four studies (Curran 1976; Guo 2001; Krupitsky 2004; Ladewig 1990) ,159 participants, RR 1.29 (95%CI 0.54‐3.11) no statistically significant difference seeAnalysis 1.6, due to the high heterogeneity (P=0.03), we applied random effect model

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatments, Outcome 6 side effects.

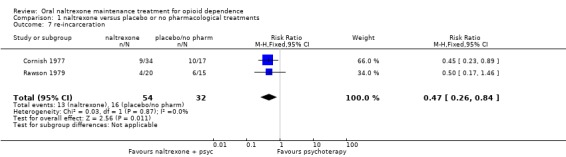

1.6 Reincarceration

two studies (Cornish 1977, Rawson 1979) , 86 participants, RR 0.47 (95%CI 0.26‐0.84), results in favour of naltrexone seeAnalysis 1.7

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatments, Outcome 7 re‐incarceration.

Comparison 2. Naltrexone versus psychotherapy

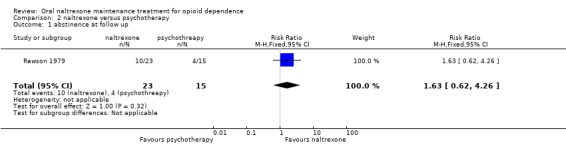

2.1 Abstinence at follow up

one study (Rawson 1979) , 38 participants, RR 1.63 (95%CI 0.62‐4,26) no statistically significant difference seeAnalysis 2.1

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 naltrexone versus psychotherapy, Outcome 1 abstinence at follow up.

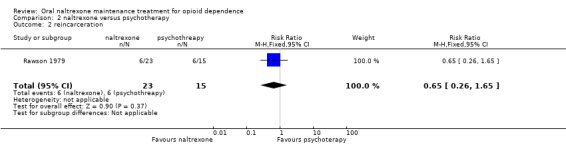

2.2 Reincarceration

one study (Rawson 1979) , 38 participants, RR 0.65 (95%CI 0.26‐1.65) no statistically significant difference seeAnalysis 2.2

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 naltrexone versus psychotherapy, Outcome 2 reincarceration.

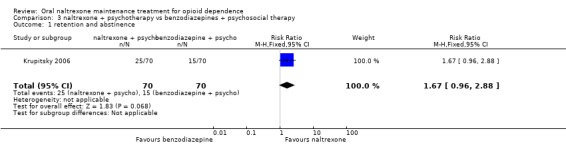

Comparison 3. Naltexone plus psychotherapy versus benzodiazepines plus psychotherapy

3.1 Retention and abstinence

one study (Krupitsky 2006) 140 participants, RR 1.67 (95%CI 0.96‐2.89) no statistically significant difference seeAnalysis 3.1

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 naltrexone + psychotherapy vs benzodiazepines + psychosocial therapy, Outcome 1 retention and abstinence.

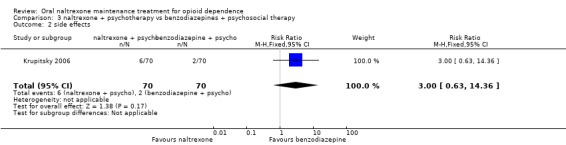

3.2 Side effects

one study (Krupitsky 2006) 140 participants, RR 3.00 (95%CI 0.63‐14.36) no statistically significant difference seeAnalysis 3.2

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 naltrexone + psychotherapy vs benzodiazepines + psychosocial therapy, Outcome 2 side effects.

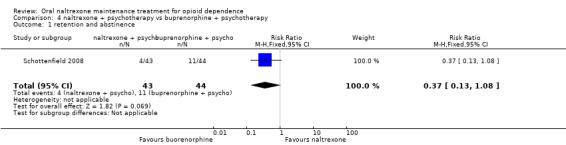

Comparison 4. Naltrexone plus psychotherapy versus buprenorphine plus psychotherapy

4.1 Retention and abstinence

one study (Schottenfield 2008) , 87 participants, RR 0.37 (95%CI 0.13‐1.08) no statistically significant difference seeAnalysis 4.1

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 naltrexone + psychotherapy vs buprenorphine + psychotherapy, Outcome 1 retention and abstinence.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Comparing naltrexone versus placebo or no treatment no statistically significant difference were noted for all the primary outcomes considered. The only outcome statistically significant in favour of naltrexone was re incarceration, RR 0.47 (95%CI 0.26‐0.84), but results came from only two studies. Considering only studies whrere patients were forced to adherence, a statisctically significant results in favour of naltrexone was found.

Comparing naltrexone versus psychotherapy, no statistically significant difference was found for the two outcome considered ( abstinence at follow up and reincarceration) but results came from a single study .

Naltrexone was not superior to benzodiazepines and to buprenorphine for retention and abstinence and side effects. Results come from a single study.

None of included studies considered mortality as an outcome.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Results of the review show that comparing oral naltrexone with placebo or no treatment no statistically significant differences were found for the primary outcomes. For the outcome "retention and abstinence" and "abstinence" alone and side effects, a statistically significant heterogeneity was found down grading the overall quality of the results.

Moreover it should be noted that most of the comparisons were underpowered, with few studies and participants included in the analyses, thing that limit the strengh of the evidence as well as the completeness and the applicability.

The main problem associated with oral naltrexone was the high drop out rate: 72% in our included studies; to overcome this problem the sustained released naltrexone has been proposed and is currently being assessed. However, a parallel Cochrane review on sustained released naltrexone (Lobmaier 2008) concluded that there is insufficient evidence to evaluate the effectiveness of sustained‐release naltrexone for treatment of opioid dependence.

A concern about lack of information on mortality data, limit the applicability of the produced evidence due the relevant problem of fatal overdoses in naltrexone treated patients.

Quality of the evidence

The majority of the studies where not of high quality. Only two studies reported information about sequence generation and only three about allocation concealment. Eight out of thirteen studies were double blind, the other were open trial. Nevertheless we think that this did not introduce bias in the main outcomes addressed in this review, because the retention in treatment is an objective measure and abstinence is assessed by urine analysis in all trials . Incomplete outcome data was addressed correctly in the majority of the studies and in any case it does not introduce bias for the outcome retention and retention and abstinence which are the main outcomes on which the review is focused.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The findings of this review suggest that oral naltrexone did not performed better than treatment with placebo or no pharmacological treatments a part from the number of participants re‐incarcerated during the study period. If oral naltrexone is compared with other pharmacological treatments such as benzodiazepine and buprenorphine, no statistically significant difference was found. The percentage of people retained in treatment in the include studies was low (28%).

The conclusion of this review is that the studies conducted to date have not allowed an adequate evaluation of oral naltrexone treatment in the field of opioid dependence. Consequently, maintenance therapy with naltrexone cannot yet be considered a treatment which has been scientifically proved to be superior to other kinds of treatment.

Naltrexone may be an efficacious adjuvant in therapy, especially for participants who fear severe consequences if they do not stop taking opioids . This target group consists of health‐care professionals, who might lose their job or parolees who risk re‐incarceration. Other highly motivated addicts may profit from naltrexone treatment. However further studies are required to confirm this impression. As described before, some circumstances may increase the probability of a positive outcome of naltrexone treatment, such as stable social contacts (spouse, family, friends), occupation, a confidential relationship with the therapist and clear instructions on the treatment itself, with participants giving their informed consent. Certainly, these conditions favour positive results in the therapy of drug addicts generally, not only in the case of naltrexone (Grey 1986) showed family support to be of significant benefit in the methadone group.

Implications for research.

RCTs evaluating effectiveness for treatment of opioid dependence should compare oral naltrexone to sustained‐release naltrexone or agonist replacement treatment with methadone or buprenorphine. Besides effectiveness, any research on naltrexone should also focus on mortality and other safety outcomes to make an analysis of harm‐benefit possible.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 28 February 2011 | Amended | After receiving a criticism, we added some information in the abstract section |

| 4 January 2011 | New search has been performed | new search, new studies |

| 4 January 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | new search, new studies, conclusions not changed |

| 20 October 2008 | Amended | Contact details updated |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1998 Review first published: Issue 1, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 26 March 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 27 October 2005 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the contact editor Dr Robert Ali.

Appendices

Appendix 1. PubMed Search Strategy

opioid‐related disorder [mesh]

(((addict*[Title/Abstract]) OR disorder*[Title/Abstract]) OR abus*[Title/Abstract]) OR dependen*[Title/Abstract]

(((((OPIUM[Title/Abstract]) OR opiate*[Title/Abstract]) OR opioid[Title/Abstract]) OR heroin[Title/Abstract]) OR methadone[Title/Abstract]) OR morphine[Title/Abstract]

#1 or #2 or #3

((naltrexone[Title/Abstract]) OR naloxone[Title/Abstract]

naltrexone [mesh]

naloxone [mesh]

#5 or #6 or #7

randomized controlled trial[pt]

controlled clinical trial[pt]

random*[tiab]

placebo[tiab]

drug therapy[mesh]

trial[tiab]

groups[tiab]

#9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15

animals [mesh] not humans [mesh]

#16 NOT #17

#4 AND #8 AND #18

limit 19 to 2005‐2010

Appendix 2. Criteria for Risk of Bias Assessment

|

Item |

Judgment |

Description |

|

| 1 | Was the method of randomization adequate? | Yes | The investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as: random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimization |

| No | The investigators describe a non‐random component in the sequence generation process such as: odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; hospital or clinic record number; alternation; judgement of the clinician; results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; availability of the intervention | ||

| Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. | ||

| 2 | Was the treatment allocation concealed? | Yes | Investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation: central allocation (including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomization); sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. |

| No | Investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments because one of the following method was used: open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | ||

| Unclear | Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. This is usually the case if the method of concealment is not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement | ||

| 3 | Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study? (blinding of patients, provider, outcome assessor) Objective outcomes |

Yes |

Blinding of participants, providers and outcome assessor and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken; Either participants or providers were not blinded, but outcome assessment was blinded and the non‐blinding of others unlikely to introduce bias. No blinding, but the objective outcome measurement are not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding |

| 4 | Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study? (blinding of patients, provider, outcome assessor) Subjective outcomes |

Yes |

Blinding of participants, providers and outcome assessor and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken; Either participants or providers were not blinded, but outcome assessment was blinded and the non‐blinding of others unlikely to introduce bias. |

| No | No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome or outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; Blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken; Either participants or outcome assessor were not blinded, and the non‐blinding of others likely to introduce bias |

||

| Unclear | Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’; | ||

| 5 | Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? For all outcomes except retention in treatment or drop out |

Yes |

No missing outcome data; Reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; Missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods All randomized patients are reported/analyzed in the group they were allocated to by randomization irrespective of non‐compliance and co‐interventions (intention to treat) |

| No | Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘As‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomization; |

||

| Unclear | Insufficient reporting of attrition/exclusions to permit judgement of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ (e.g. number randomized not stated, no reasons for missing data provided; number of drop out not reported for each group); |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. naltrexone versus placebo or no pharmacological treatments.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 retention in treatment | 2 | 83 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.72, 1.91] |

| 2 retention and abstinence, all patients | 6 | 393 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.43 [0.72, 2.82] |

| 3 retention and abstinence, patients forced to abstinence | 3 | 230 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.93 [1.66, 5.18] |

| 4 abstinence | 4 | 143 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.39 [0.61, 3.17] |

| 5 abstinence at follow up | 3 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.80, 2.05] |

| 6 side effects | 4 | 159 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.54, 3.11] |

| 7 re‐incarceration | 2 | 86 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.47 [0.26, 0.84] |

Comparison 2. naltrexone versus psychotherapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 abstinence at follow up | 1 | 38 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.63 [0.62, 4.26] |

| 2 reincarceration | 1 | 38 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.26, 1.65] |

Comparison 3. naltrexone + psychotherapy vs benzodiazepines + psychosocial therapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 retention and abstinence | 1 | 140 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.96, 2.88] |

| 2 side effects | 1 | 140 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.63, 14.36] |

Comparison 4. naltrexone + psychotherapy vs buprenorphine + psychotherapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 retention and abstinence | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.13, 1.08] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Cornish 1977.

| Methods | randomised, controlled trial. ratio of patients receiving naltrexone to those receiving placebo: 2:1 not blind | |

| Participants | 51 North American voluntary federal probationers or parolees with a history of opioid addiction; average age :39 years; 90% male; 24% white, 62% African American, 14% Latino Americans. Average of 2.9 years of prior incarcerations | |

| Interventions | naltrexone plus probation programme and minimal counselling (34) versus probation programme and minimal counselling alone (17), monetary reward. Outpatients. Probation programme: twice weekly contact with the probation officer and for urine analysis. Counseling: three session per week during the first 2 weeks of the study. Participants gained $ 25.00 at the end of the study. Naltrexone: 25 mg/day for 2 days, then 50 mg/day for 3 days. 1 week after the initiation stabilization with 100 mg on Tuesday and 150 mg on Friday duration: 6 month trial. | |

| Outcomes | retention in treatment re incarceration | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | quote "subjects were assigned at random in a 2:1 ratio to naltrexone or control" |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | quote "subjects were assigned at random in a 2:1 ratio to naltrexone or control" |

| Blinding? objective outcomes | Low risk | open label trial, but the outcomes are unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | High risk | open label |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | |

Curran 1976.

| Methods | randomised , placebo‐controlled trial double‐blind | |

| Participants | 38 North American dependent parolees or probationers; mean age: 26 years; 68% unmarried; 5% completed the high school; all with criminal records with an average of 9 arrests. | |

| Interventions | naltrexone (19) versus placebo (19) ; outpatients. naltrexone: six days a week for the first two months, then three times a week. Doses not specified study duration: 9 month trial | |

| Outcomes | retention in treatment use of substance (urine analysis) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | method of sequence generation not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | method for allocation concealment not described |

| Blinding? objective outcomes | Low risk | double blind |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | Low risk | double blind |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | number of subject who withdrawn from the study and reason reported for each group |

Guo 2001.

| Methods | randomised placebo controlled trial; used the table of random number. ratio of patients receiving naltrexone to those receiving placebo: 2:1 double blind. Multicenter study. | |

| Participants | 49 Chinese patients who completed detoxification without using opiates for at least 5‐7 days before naltrexone treatment. Mean age: 24,96 (naltrexone) 26,76 (placebo). Male: 88,57% (naltrexone),92,86% (placebo). Educational level below junior high school: 68% (naltrexone) 78,57% (placebo); unemployed : 57,14% (naltrexone) 35,71% (placebo) | |

| Interventions | naltrexone 50 mg/day(35) vs placebo (14). Outpatients setting duration: 6 month study | |

| Outcomes | use of substance of abuse: n. of patients abstinent every month and at the end of the study. adverse effects | |

| Notes | withdrawn from the study: data not given. Results on use of substances presented for 34 patients on naltrexone and 12 participants on placebo | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | quote: " the randomisation was performed according to the tables of random permutation" |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | method for allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding? objective outcomes | Low risk | the study is labelled as double blind, but is also reported that " to investigate the optimal dose for Chinese patients, naltrexone was titrated according to the patients response COMMENT:The lack of blinding is unlikely to bias objective outcomes |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | Unclear risk | the study is labelled as double blind, but is also reported that " to investigate the optimal dose for Chinese patients, naltrexone was titrated according to the patients response |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | not reported how many patients dropped out form the studies and the different outcomes are measured on different numbers of patients |

Hollister 1978.

| Methods | multicentric randomised placebo controlled double blind | |

| Participants | 192 North American male opioid addicts: (1) street addicts recently detoxified (42) (2) methadone users (58) (3) former addicts currently drug free following incarceration or participation in a drug‐free therapeutic program (92) | |

| Interventions | naltrexone vs. placebo. Not specified the number of patients randomised to each group. Outpatients Detoxification with methadone at tapered doses for 21 days followed by 7‐14 days with inert methadone vehicle for heroin users. Detoxification with methadone at tapered doses for 4‐8 weeks followed by 7‐14 days with inert methadone vehicle for methadone users. Naltrexone: gradually increasing up to the dose of 100 or 150 mg on the seventh day. Then 100 mg /day and 150 mg on Saturday. Dose not given on Sunday. Study duration: 9 months | |

| Outcomes | use of primary substance of abuse (urine analysis) retention in treatment results at follow up six month after the end of treatment | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | method of sequence generation not reported |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | method to obtain allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding? objective outcomes | Low risk | double blind. "Administration of treatment was carried out on a double blind basis; Naltrexone and placebo were in for of a syrup similar in appearance and taste" |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | Low risk | double blind. "Administration of treatment was carried out on a double blind basis; Naltrexone and placebo were in for of a syrup similar in appearance and taste" |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Results described only for 124 patients. Information not given for the others |

Krupitsky 2004.

| Methods | randomised controlled trial, double blind; | |

| Participants | 52 Russian opioid dependent patients abstinent from heroin for at least one week. Mean age: 22 years; Patients dependent on heroin for 2,5 years on average. male: 80%. Patients completed the secondary school: 88% | |

| Interventions | naltrexone plus biweekly psycho social therapy (27) versus placebo plus biweekly psychosocial therapy (25). naltrexone: doses and frequency of administration not specified Study duration : 6 months | |

| Outcomes | retention in treatment use of substance of abuse (urine analysis) side effects | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Methos of sequence generation not reported |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | "Pharmacy staff of the Pavlov University prepared naltrexone and placebo in identically appearing capsules containing a riboflavine marker. A Amaster code was kept art Pavlov so the blind could be broken in case of emergency. Medication were dispensed double blind at each counselling session" |

| Blinding? objective outcomes | Low risk | double blind; naltrexone and placebo in identically appearing capsules containing a riboflavine marker. |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | Low risk | double blind, naltrexone and placebo in identically appearing capsules containing a riboflavine marker. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | number of drop out reported for each group; reason given. Excluding patients who dropped out because relapsed to heroin 7 patients dropped out from naltrexone group and 3 from placebo group |

Krupitsky 2006.

| Methods | randomised controlled trial double blind, double dummy |

|

| Participants | 280 patients with primary diagnosis of opioid dependence according to DSM IV , abstinence from heroin and other substance of abuse , including alcohol for at last one week, at least one relative who was willning to participate in treatment. Mean age 23.6 years, male: 72.25% |

|

| Interventions | group A: naltrexone 50 mg/day + fluoxeitine 20 mg/day + drug counselling (n. 70) group B: naltrexone 50 mg/day + fluoxeitine placebo + drug counselling(n. 70) group C: naltrexone placebo+ fluoxeitine 20 mg/day + drug counselling(n. 70) group D: naltrexone placebo + fluoxeitine placebo + drug counselling(n. 70) Study duration : 6 months |

|

| Outcomes | retention and no relapsing use of alcohol and other substance of abuse craving side effects |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | method of sequence generation not reported |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | method for allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding? objective outcomes | Low risk | double blind, double dummy |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | Low risk | double blind, double dummy |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | outcomes other than retention and relapsing measured only on patients who remained in treatment |

Ladewig 1990.

| Methods | randomised, controlled trial not blind | |

| Participants | 20 detoxified opioid addicts male and female; age range: 20‐35 years; opioid free for at least 10 days; | |

| Interventions | naltrexone plus psychotherapy (15) versus psychotherapy alone (5); outpatients. naltrexone: induction: 50 mg/day for three weeks; then Monday 100 mg, Wednesday 100 mg, Friday 150 mg. Psychotherapy: daily group therapy plus weekly individual therapy study duration: information not reported (duration of treatment of patients: min 34 max 124 days) | |

| Outcomes | use of substance af abuse measured by urine analysis adverse effects | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | information not reported |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | information not reported |

| Blinding? objective outcomes | Low risk | open label trial, but the outcomes are unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | High risk | open label |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | results reported for 14 of 15 patients in the intervention group and for 3 of 5 in the control group.. Information not given on the patients lost |

Lerner 1992.

| Methods | randomised placebo controlled trial double blind | |

| Participants | 31 Israeli newly abstinent patients after opioid detoxification in housing projects; opioid free for 1 up to 2 weeks.; mean age: 26.6 years; mean duration of opoid use: 33,61 months | |

| Interventions | 2 months: naltrexone (15) versus placebo (16), both group received psychotherapy and counselling. Outpatients. Naltrexone: 12,5 mg, 25 mg, 50 mg on the first, second and third day. %0 mg/day for the following 7 days. Then 100 mg on Monday, 100 mg on Wednesday and 150 mg on Friday for two months duration. 2 month study follow up: 1 year | |

| Outcomes | use of primary substance at the end of treatment (number of subject opioid free) use of primary substance at one year follow up | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | method of sequence generation not reported |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | "Random assignment was done by an investigator who had no contact with the subjects. " |

| Blinding? objective outcomes | Low risk | double blind. "The randomisation code was not available to the investigators who treated the subjects" |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | Low risk | double blind. "The randomisation code was not available to the investigators who treated the subjects" |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | analysis done on the intention to treat principle |

Rawson 1979.

| Methods | randomised controlled trial not blinded | |

| Participants | 181 North American male heroin addicts ; 39% white, 9% black, 52% Indians. Mean age: 25,9 years. Mean years addicted to heroin: 7,9. | |

| Interventions | naltrexone alone (55) versus naltrexone plus behaviour therapy (55) versus behaviour therapy alone (71). Outpatients. Patients who completed the entry probation and received the intervention: naltrexone (23), naltrexone plus behavior (20) behavior (15) Naltrexone doses: 50 mg/day for the first two weeks; for the next 6 weeks 50 mg twice/week and 100 mg on Saturday; Then 100 mg twice/week and 150 mg on Friday for 16 weeks. Finally 16 weeks of gradually decreasing the dose. Behavioral therapy: contingency contracting, relaxation training ,self‐control procedures, role playing on how to refuse heroin study duration: 10 months | |

| Outcomes | participants who completed the entry probation into the program: they had to complete a one week inpatient detoxification program and give three clear urine in the second week. Or they could spend the two weeks on the street but giving clean urine every two days retention in treatment for at least six months incarceration use of substance of abuse | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Quote: "clients were randomly assigned to one of the three treatment programs |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Quote: "clients were randomly assigned to one of the three treatment programs |

| Blinding? objective outcomes | Low risk | open label trial, but the outcomes are unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | High risk | open label |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | number of withdrawal reported for each group, no significance difference between groups |

San 1991.

| Methods | randomised placebo controlled trial double‐blind | |

| Participants | 50 Spanish opioid addicts(DSM‐III‐R criteria) after detoxification ; male: 78.6 %(naltrexone), 72,7 %(placebo); mean age: 26.1 (naltrexone), 27,3 (placebo); employed: 75% (naltrexone), 54,5% (placebo) | |

| Interventions | naltrexone (28) vs placebo (22) 1st month: naltrexone for all patients: 50 mg/day for the first week; from week two to four patients received two 100 mg and one 150 mg dose per week. 2nd month: naltrexone (28) vs. placebo (22) Detoxification and induction to naltrexone in hospital setting, naltrexone maintenance an out‐patients basis. duration: 6 month study plus 6 month follow up | |

| Outcomes | use of primary substance: n. of participants abstinent retention in treatment results at follow up: 1 year: use of primary substance: n. of participants abstinent | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | method of sequence generation not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | method for allocation concealment not described |

| Blinding? objective outcomes | Low risk | double blind |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | Low risk | double blind. Quote" a further measure undertaken to preserve the double blind nature of the trial was the addiction of quinine to placebo capsules to ensure the same organoleptic characteristics as naltrexone capsules" |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | number of subjects who dropped out and reason reported for each group |

Schottenfield 2008.

| Methods | randomised controlled trial double blind, double dummy |

|

| Participants | 126 opioid dependent patients according to DSM IV. Mean age: 37 years; male percentage not reported | |

| Interventions | group A naltrexone 50 mg/day plus buprenorphine placebo + drug counselling (n: 43) group B: buprenorphine 8mg/day plus naltrexone placebo plus drug counselling (n. 44) group C: buprenorphine placebo plus naltrexone placebo plus drug counselling (n. 39) length of study: 3 months |

|

| Outcomes | retention in treatment retention in treatment without relapsing days to first heroin use days to heroin relapse ( three consecutive urine positive tests o one positive followed by two consecutive mising tests |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | quote: " a simple complete randomisation sequence was generated by a computer programme " |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | " the sequence was maintained in the USA and disclosed only to the study pharmacist in Malaysia for preparation of double blind, double dummy drugs " |

| Blinding? objective outcomes | Low risk | double blind, double dummy |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | Low risk | double blind, double dummy |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | three patients withdrawn from the study, one from each group |

Shufman 1994.

| Methods | randomised placebo controlled trial double‐blind | |

| Participants | 32 male Israeli heroin addicts after detoxification abstinent for at least 10 days; mean age:32 years; 72% marries, 84 did not complete the secondary education, 50% involved in criminal activity | |

| Interventions | behavioral and supportive psychotherapy plus naltrexone (16) vs. behavioral and supportive psychotherapy plus placebo (16) 50 mg/week for the first two weeks at the visit to the clinic; 50 mg at the visit to the clinic plus two more tablets to take at home during the weekend (total 150 mg/week) for the following weeks Outpatients setting study duration: 12 weeks | |

| Outcomes | retention in treatment use of primary substance: patient drug free at the end of treatment adverse effects | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | method of sequence generation not reported |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | method for allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding? objective outcomes | Low risk | double blind |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | Low risk | double blind |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | number of subjects who dropped out and reason reported for each group |

Stella 2005.

| Methods | randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 56 patients with a diagnosis of opioid dependence according to DSM IV . Compltete detoxification obtained by methadone or symptomatic therapy . Mean age not reported, 51 males. | |

| Interventions | group A: naltrexone 50 mg/day plus psychosocial support(n.14) Group B: naltrexone 50 mg/day plus placebo plus psychosocial support(n.14) Group C: naltrexone 50 mg/day plus prazepam plus psychosocial support(n.14) Group D: psychosocial support(n.14) Duration of trial: 6 months |

|

| Outcomes | patient opiate free at the end of trial patients with positive urine for other substance of abuse side effects insomnia, panic attack, hyperexcitability |

|

| Notes | only groups B and C were double blind | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | method of sequence generation not reported |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | method for allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding? objective outcomes | Low risk | only groups comparing prazepam versus placebo were double blind. Comment: the outcomes are unlikely to be biased by lack of blnding |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | High risk | only groups comparing prazepam versus placebo were double blind. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | no drop out form the study |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Altman 1976 | Excluded as the study design and the outcomes were not in the inclusion criteria of the review: cross‐over study and heroin self‐administration |

| Anton 1981 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: participants selected retrospectively, there is not a control group, all received naltrexone |

| Arndt 1984 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: participants selected retrospectively. |

| Brahen 1977 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: cross‐over study |

| Brahen 1978 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review:not controlled study |

| Callahan 1980 | Excluded as the type of intervention was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: all participants received naltrexone |

| Crowley 1985 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: cross‐over study |

| Gerra 1995 | Excluded as the type of intervention was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: in the experimental interventions group participants received naltrexone plus clonidine |

| Greenstein 1984 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: not randomised controlled study |

| Grey 1986 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: observational study |

| Hollister 1977 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: not randomised controlled study |

| Hurzeler 1976 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: not randomised controlled study |

| Judson 1981 | Excluded as the type of intervention was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: all participants received naltrexone |

| Judson 1983 | Excluded as the type of intervention was not in the inclusion criteria: LAAM treatment, introduction onto naltrexone |

| Judson 1984 | Excluded as the type of intervention was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: LAAM treatment |

| Lewis 1978 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: not randomised controlled study |

| Martin 1973 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: cross‐over study |

| Mello 1981 | Excluded because it is not possible to extract the data about any outcome considered in the review. |

| Navaratnam 1994 | Excluded as the type of intervention was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: naltrexone as a basic treatment in a study performed on other pharmacological effects |

| Nunes 2006 | Excluded as the type of intervention was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: behavioral intervention to enhance compliance with naltrexone |

| O`Brien 1975 | Excluded as the type of intervention was not in the inclusion criteria of review: naltrexone as a basic treatment in a study performed on other pharmacological effects |

| Osborn 1986 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: observational study (same data of Grey 1986) |

| Raby 2009 | Excluded because the type of outcome was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: cannabis use as a factor enhancing adherence to naltrexone treatment |

| Rea 2004 | Excluded as the type of intervention was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: no control group, naltrexone at different doses |

| Resnick 1974 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: not controlled study |

| Rothenberg 2002 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: not controlled study |

| Sideroff 1978 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: not controlled study |

| Taintor 1975 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: not controlled study |

| Tennant 1984 | Excluded as the study design was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: not controlled study |

| Volavka 1976 | Excluded as the type of intervention was not in the inclusion criteria of the review: naltrexone as a basic treatment in a study performed on other pharmacological effects |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Grinenko 2003.

| Methods | RCT; double blind, placebo controlled trial |

| Participants | heroin addicts after detoxification; number of participants not reported in the abstract |

| Interventions | naltrexone (doses not reported) versus placebo |

| Outcomes | relapse to heroin |

| Notes |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Blondell 2009.

| Trial name or title | Comparison of Buprenorphine/Naloxone with Naltrexone in opioid dependent patients |

| Methods | 2 arms randomised comparative effectiveness pharmacotherapy clinical trial |

| Participants | Outpatients facilities participants between 16 and 25 years old who have clear evidence of a substance use disorder with opioid dependence and live with at least one parent |

| Interventions | buprenorphine/naloxone versus naltrexone |

| Outcomes | Retention in treatment, self reported opioid craving, self reported drug use with urine toxicology confirmation |

| Starting date | October 2009; the study is currently recruiting participants |

| Contact information | Responsible Party: Department fo Family Medicine, SUNY, Buffalo |

| Notes |

Contributions of authors

Minozzi substantially updated the review, Minozzi, Amato, Vecchi assessed studies for inclusion and undertook data extraction. Inclusion decisions and the overall process were confirmed by consultation between all reviewers. Amato drafted the background and conclusions. Kirchmayer and Verster read the draft. Davoli supervised.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Department of Epidemiology, ASL RM E, Italy.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

None

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Cornish 1977 {published data only}

- Cornish JW, Metzger D, Woody GE, Wilson D, McLellan AT, Vandergrift B, et al. Naltrexone pharmacotherapy for opioid dependent federal probationers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 1997;14(6):529‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Curran 1976 {published data only}

- Curran S, Savage C. Patients response to naltrexone: issues of acceptance, treatment effects, and frequency of administration. NIDA Research Monograph Series 1976;9:67‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guo 2001 {published data only}

- Guo S, Jiang Z, Wu Y. Efficacy of naltrexone Hydrochloride for preventing relapse among opiate‐dependent patients after detoxification. Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry 2001;11(4):2‐8. [Google Scholar]

Hollister 1978 {published data only}

- Hollister LE. Clinical evaluation of naltrexone treatment of opiate‐dependent individuals. Report of the National Research Council Committee on Clinical Evaluation of Narcotic Antagonists. Archives of General Psychiatry 1978;35(3):335‐40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Krupitsky 2004 {published data only}

- Krupitsky EM, Zvartau EE, Masalov DV, Tsoi MV, Burakov AM, Egorova VY, et al. Naltrexone for heroin dependence treatment in St Petersburg, Russia. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 2004;26(4):285‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Krupitsky 2006 {published data only}

- Krupitsky EM, Zvartau EE, Masalov DV, Tsoy MV, Burakov AM, Egorova VY, et al. Naltrexone with or without fluoxitine for preventing relapse to heroin addiction in St. Petersburg, Russia. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 2006;31:319‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ladewig 1990 {published data only}

- Ladewig D. Naltrexone ‐ an effective aid in the psychosocial rehabilitation process of former opiate dependent patients. Therapeutische Umschau 1990;47(3):247‐50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lerner 1992 {published data only}

- Lerner A, Sigal M, Bacalu A, Shiff R, Burganski I, Gelkopf M. A naltrexone double‐blind placebo controlled study in Israel. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences 1992;29(1):36‐43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rawson 1979 {published data only}

- Rawson RA, Glazer M, Callahan EJ, Liberman RP. Naltrexone and behaviour therapy for heroin addiction. NIDA Research Monograph Series 1979;25:26‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

San 1991 {published data only}

- San L, Pomarol G, Peri JM, Olle JM, Cami J. Follow‐up after a six‐month maintenance period on naltrexone versus placebo in heroin addicts. British Journal of Addiction 1991;86(8):983‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schottenfield 2008 {published data only}

- Schottenfield RS, Chawaski MC, Mazian M. Maintenance treatment with buprenorphine and naltrexone for heroin dependence in Malaysia: a randomised, double blind , placebo controlled trial. Lancet 2008;371:2192‐200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shufman 1994 {published data only}

- Shufman EN, Porat S, Witzum E, Gandacu C, Bar‐Hamburger R, Ginath Y. The efficacy of naltrexone in preventing re abuse of heroin after detoxification. Biological Psychiatry 1994;35(12):935‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stella 2005 {published data only}

- Stella L, D'Ambra C, Mazzeo F, Capuano A, Franco F, Avolio A, et al. Nalltrexone plus benzodiazepines aids abstinence in opioid‐dependents patients. Life Science 2005;77:2717‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Altman 1976 {published data only}

- Altman JL, Meyer RE, Mirin SM, McNamee HB, McDougle M. Opiate antagonists and the modification of heroin self‐administration behaviour in man: an experimental study. The International Journal of the Addictions 1976;11(3):485‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Anton 1981 {published data only}

- Anton RA, Hogan I, Jalali B, Riordan CE, Kleber HD. Multiple family therapy and naltrexone in the treatment of opiate dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 1981;8(2):157‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arndt 1984 {published data only}

- Arndt I, Lellan AT, O´Brien CP. Abstinence treatments for opiate addicts: therapeutic community or naltrexone?. NIDA Research Monograph Series 1984;49:275‐81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brahen 1977 {published data only}

- Brahen LS, Capone T, Wiechert V, Desiderio D. Naltrexone and cyclazocine. A controlled treatment study. Archives of General Psychiatry 1977;34(10):1181‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brahen 1978 {published data only}

- Brahen LS, Capone T, Heller RC, Linden SL, Landy HJ, Lewis MJ. Controlled clinical study of naltrexone side effects comparing first‐day doses and maintenance regimens. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 1978;5(2):235‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Callahan 1980 {published data only}

- Callahan EJ, Rawson RA, McCleave B, Arias R, Glazer M, Liberman RP. The treatment of heroin addiction: naltrexone alone and with behaviour therapy. The International Journal of the Addictions 1980;15(6):795‐807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Crowley 1985 {published data only}

- Crowley TJ, Wagner JE, Zerbe G, Macdonald M. Naltrexone‐induced dysphoria in former opioid addicts. American Journal of Psychiatry 1985;142(9):1081‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gerra 1995 {published data only}

- Gerra G, Marcato A, Caccavari R, Fontanesi B, Delsignore R, Fertonani G, et al. Clonidine and opiate receptor antagonists in the treatment of heroin addiction. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 1995;12(1):35‐41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Greenstein 1984 {published data only}

- Greenstein RA, Arndt IC, McLellan AT, O´Brien CP, Evans B. Naltrexone: a clinical perspective. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1984;45(9):25‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Grey 1986 {published data only}

- Grey C, Osborn E, Reznikoff M. Psychosocial factors in outcome in two opiate addiction treatments. Journal of Clinical Psychology 1986;42(1):185‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hollister 1977 {published data only}

- Hollister LE, Schwin RL, Kasper P. Naltrexone treatment of opiate‐dependent persons. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 1977;2(3):203‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hurzeler 1976 {published data only}

- Hurzeler M, Gerwirtz D, Kleber H. Varying clinical contexts for administering naltrexone. NIDA Research Monograph 1976;9:48‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Judson 1981 {published data only}