Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) infections are increasingly multidrug resistant and cause healthcare associated pneumonia, a major risk factor for acute lung injury (ALI)/ acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Adenosine is a signaling nucleoside with potential opposing effects; adenosine can either protect against acute lung injury via adenosine receptors or cause lung injury via adenosine receptors or equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT)-dependent intracellular adenosine uptake. We hypothesized that blockade of intracellular adenosine uptake by inhibition of ENT1/2 would increase adenosine receptor signaling and protect against P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury. We observed that P. aeruginosa (strain: PA103) infection induced acute lung injury in C57BL/6 mice in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Using ENT1/2 pharmacological inhibitor, nitrobenzylthioinosine (NBTI), and ENT1-null mice, we demonstrated that ENT blockade elevated lung adenosine levels and significantly attenuated P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury, as assessed by lung wet-to-dry weight ratio, BAL protein levels, BAL inflammatory cell counts, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and pulmonary function (total lung volume, static lung compliance, tissue damping, and tissue elastance). Using both agonists and antagonists directed against adenosine receptors A2AR and A2BR, we further demonstrated that ENT1/2 blockade protected against P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury via activation of A2AR and A2BR. Additionally, ENT1/2 chemical inhibition and ENT1 knockout prevented P. aeruginosa-induced lung NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Finally, inhibition of inflammasome prevented P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury. Our results suggest that targeting ENT1/2 and NLRP3 inflammasome may be novel strategies for prevention and treatment of P. aeruginosa-induced pneumonia and subsequent ARDS.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, acute lung injury, equilibrative nucleoside transporters, pneumonia, NLRP3 inflammasome

Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is characterized by non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema and widespread inflammation (1) and affects approximately 3 million patients worldwide annually with mortality from 35–46% (2, 3). Pulmonary (direct) and systemic (indirect) infections are among the major risk factors for ARDS (1). Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), a gram-negative pathogen with increasing prevalence of multidrug resistance (MDR) (4), is one of the top three pathogens causing 10.1% of hospital-acquired infections and accounting for 16.5% of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) with attributable mortality up to 41.9% (5). In addition to causing healthcare-associated pneumonia (6–8), sepsis is another major clinical manifestations of P. aeruginosa infection. Previously effective antibiotic management in critically ill patients has become ineffective due to MDR, leading to increased mortality and worse outcomes (5). Therefore, it is necessary to develop novel non-antibiotic therapeutics for P. aeruginosa infections and subsequent ARDS.

Adenosine, a signaling nucleoside, has contrasting effects. Acutely elevated adenosine protects against inflammation and acute lung injury (9–13), whereas chronically sustained increased adenosine is detrimental to the lungs (14). Extracellular adenosine signals via engagement of its four G protein-coupled adenosine receptors. ADORA 1 (A1R) and ADORA 3 (A3R) couple to the Gi family proteins to inhibit adenylyl cyclase, whereas ADORA 2A (A2AR) and ADORA 2B (A2BR) couple to the Gs family proteins to activate adenylyl cyclase, thereby amplifying cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/ protein kinase A (PKA) signaling and calcium mobilization (15, 16). Acute activation of A2AR and A2BR ameliorates pulmonary edema and enhances endothelial barrier integrity (10, 12, 13, 17). However, the downstream intracellular signaling of adenosine receptor-mediated protection against acute lung injury is not well understood.

Extracellular adenosine is metabolized into inosine via cell surface adenosine deaminase (ADA) and/or terminated by intracellular uptake facilitated by equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENTs). ENT1 and ENT2 are major adenosine transporters expressed in lung microvascular endothelial cells and alveolar epithelial cells (18–20). We have previously shown that sustained elevated adenosine causes lung endothelial cell barrier dysfunction and apoptosis via ENT1/2-dependent mechanisms (21, 22), suggesting that intracellular adenosine uptake is detrimental to lung endothelial cells. Inhibition of ENT1/2 has been shown to attenuate acute lung injury induced by hypoxia (23), high-pressure mechanical ventilation (20) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (19). Whether inhibition of ENT1/2 protects against P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury is unknown. Endothelial cells express ENT1 (24) and ENT2 (19). Intracellular adenosine uptake adversely affects endothelial barrier function and causes endothelial apoptosis (21, 22). We therefore hypothesized that blocking intracellular adenosine uptake by inhibition of ENT1/2 and simultaneous increase in extracellular adenosine signaling would protect against P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury.

The inflammasomes are cytosolic multimeric protein platforms that assemble in response to stress or infections and are central to innate immunity and inflammation (25). The nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (Nod)-like receptor (NLR) family of inflammasomes belongs to a class of intracellular pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and/or host-derived damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Nod leucine-rich repeat (LRR) and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, a member of the NLR inflammasome family, is activated by a wide range of stimuli, including PAMPs and DAMPs. NLRP3 interacts with an adaptor, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-recruitment domain (ASC), leading to self-cleavage (activation) of caspase-1 and subsequent cleavage and release of mature IL-1β and IL-18 (26). IL-18 is elevated in plasma of patients with sepsis- or trauma-induced ARDS (27), highlighting a potential role of inflammasome in pathogenesis of human ARDS. NLRP3 inflammasome activation has been implicated in several animal models of acute lung injury induced by LPS (28), polymicrobial sepsis (29), mechanical ventilation (27), hyperoxia (30), and hemorrhagic shock (31). Mice deficient in interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor (IL-1R) (32) or IL-18 (33) are protected from P. aeruginosa pneumonia, suggesting that inflammasome activation contributes to P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury. Since IL-1R and IL-18 can be activated by many pathways other than NLRP3 inflammasome, it is unknown whether the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by P. aeruginosa infection. It is also unknown whether the NLRP3 inflammasome activation mediates P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury.

In this study we demonstrate that pharmacological inhibition of ENT1/2 effectively prevented P. aeruginosa-induced lung edema, inflammation, and decline in lung function. ENT1 null mice were partially protected from P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury. We further demonstrate that ENT1/2 inhibition acted via extracellular adenosine-mediated activation of A2AR and A2BR. Both ENT1/2 pharmacological inhibition and ENT1 knockout prevented P. aeruginosa-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation. These results suggest that targeting ENT1/2 and NLRP3 inflammasome may be novel strategies for prevention and/or treatment of P. aeruginosa-induced pneumonia and subsequent ARDS.

Materials and Methods

Reagents:

PSB1115 (4-(2,3,6,7-Tetrahydro-2,6-dioxo-1-propyl-1H-purin-8-yl)-benzenesulfonic acid), ZM241385 (4-(2-[7-Amino-2-(2-furyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[2,3-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol), BAY60–6583 (2-[[6-Amino-3,5-dicyano-4-[4-(cyclopropylmethoxy)phenyl]-2-pyridinyl]thio]-acetamide), and CGS21680 (4-[2-[[6-Amino-9-(N-ethyl-β-D-ribofuranuronamidosyl)-9H-purin-2-yl]amino]ethyl]benzenepropanoic acid hydrochloride) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Minneapolis, MN). Nitrobenzylthioinosine (NBTI), dipyridamole, αβ-methylene ADP, and 5’-deoxycoformycin and Ac-YVAD-cmk were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Mice:

Male 8-weeks old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). ENT1 null mice were obtained from Dr. Doo-Sup Choi (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). Adult males and females of ENT1 null mice and sex-, age- and weight-matched wild type littermates were used. All animal experiments were performed according to the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center for the humane use of experimental animals (IACUC# 2016–003). Standard housing conditions were used (12-h: 12-h light/dark cycle, 68–72°F, 30–70% humidity). Animals were maintained in ventilated racks with automated water systems and were fed standard chow ad libitum.

Intratracheal administration of bacteria:

P. aeruginosa (strain: PA103) was a gift from Dr. Troy Stevens (University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL) and maintained according to previously described protocols (34). Briefly, PA103 was grown on solid Lysogeny Broth (LB) agar plate for 16 hours and then several colonies were resuspended in sterile saline. The concentrations of PA103 suspensions were first estimated by optical density at a wavelength of 600 nm using spectrophotometer (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The actual amounts of instilled bacteria for each animal experiment were determined by serial dilution and standard plate counting of colony forming units (CFU) grown on LB agar plates. For intratracheal instillation of bacteria, mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane and then intratracheally instilled with 50 μL (1–5x 105 CFU) of PA103, as described in each figure legend, or equal volume (50 μL) of sterile saline. Acute lung injury was assessed at 4h up to 1 week after instillation of PA103.

Lung function assessment:

Lung mechanics were measured using the FlexiVent system and FlexiWare software (SCIREQ, Montreal, Canada), as previously described (21). Mice were deeply anesthetized via i.p. injection of Ketamine (200 mg/kg) and Xylazine (15 mg/kg). While anesthetized, mice were intratracheally intubated with a calibrated 20-gauge beveled catheter and ventilated via the FlexiVent ventilator at 10 mL/kg constant tidal volume and 150 breaths per minute respiratory rate. Total lung capacity (TLC), static lung compliance (Cst), tissue damping (G), and tissue elastance (H) were assessed using FlexiWare software according to manufacturer recommendations.

Lung wet/dry weight ratio:

As previously described (35), after mice were euthanized by Pentobarbital (120 mg/kg, i.p. injection), the lungs were immediately harvested and weighed. The lungs were dried for 48h at 80°C and weighed again. The ratio of lung wet-to-dry weight was calculated.

Protein content and inflammatory cell counts in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid:

Mice were anesthetized with Ketamine (75 mg/kg) and Xylazine (5 mg/kg) cocktail via i.p. injection. Mouse lungs were then lavaged once with 600 μL of sterile saline using 1-ml syringe via a tracheal catheter. Total protein concentrations in BAL fluid were assessed by DC protein assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Total inflammatory cell counts in BAL fluid were assessed by TC20 automated cell counter (BioRad, Hercules, CA), as previously described (12, 36). The proportions of BAL macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes and eosinophils were assessed by Diff Quik staining of BAL cytospin slides and the total numbers of macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes and eosinophils in BAL fluid were calculated based on total inflammatory cell counts and individual cell proportions.

Cytokines and chemokines in lung homogenates and BAL fluid:

Lung tissue and BAL fluid were collected and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Lung tissue was homogenized immediately before measurement of cytokines. TNFα and IL-6 (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), IL-1β (BioLegend, San Diego, CA), macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2), and KC (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits, per manufacturer recommendations.

Bacterial clearance:

Mice were anesthetized with Ketamine (75 mg/kg) and Xylazine (5 mg/kg) cocktail via i.p. injection. Mouse lungs were then lavaged with 600 μL of sterile saline using 1-ml syringe via a tracheal catheter at differing time points after intratracheal administration of PA103. Under sterile conditions, BAL fluid was subjected to serial 10-fold dilutions and cultured 16 hours on LB agar plates. Bacterial CFU were manually counted.

Adenosine quantification:

Mouse lungs were lavaged with nucleoside preservation cocktail (dipyridamole, αβ-methylene ADP, and 5’-deoxycoformycin) for BAL fluid collection. BAL fluid and lung tissue were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. Nucleosides were extracted using 0.4 N perchloric acid and adenosine was quantified using reverse- phase HPLC, as previously described (12, 21, 37).

Immunoblot analysis:

Lung tissue was homogenized and then subjected to total protein assay and western blot analysis. Antibodies directed against NLRP3 (AdipoGen Life Sciences, San Diego, CA), ASC (AdipoGen Life Sciences, San Diego, CA), pro-caspase-1, and active (p20) caspase-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas) were used to determine protein expression by BioRad ChemiDoc Imaging Systems. Actin, β-actin, and GAPDH were used as protein loading controls. Densitometry of immunoblots was performed using ImageJ software.

Data Analysis:

Biological replicates (n=4–10) with at least 3 technical replicates were used in this study. For experiments using ENT1 null mice, sex-, age- and weight-matched wild type control littermates were used. Mice were randomized into treatment groups. All endpoint measurements were done in a blinded manner. The specificity of antibodies was verified by vendors and confirmed. Data are presented as means ± standard error (SE). The difference between two means was assessed using Student’s T test. The differences among three or more means were assessed using one- or two- way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Fisher’s LSD post hoc test. Differences among means are considered statistically significant when p<0.05.

Results

P. aeruginosa caused acute lung injury in a dose- and time-dependent manner

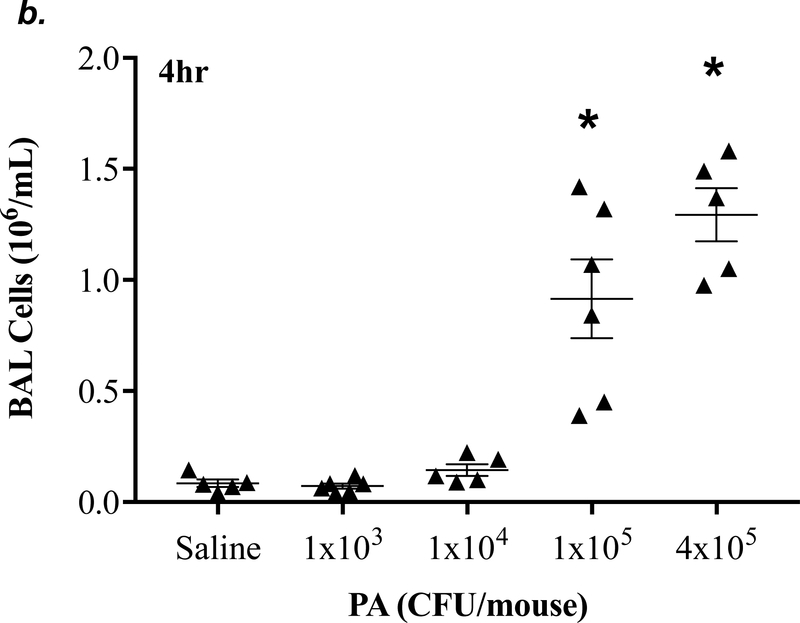

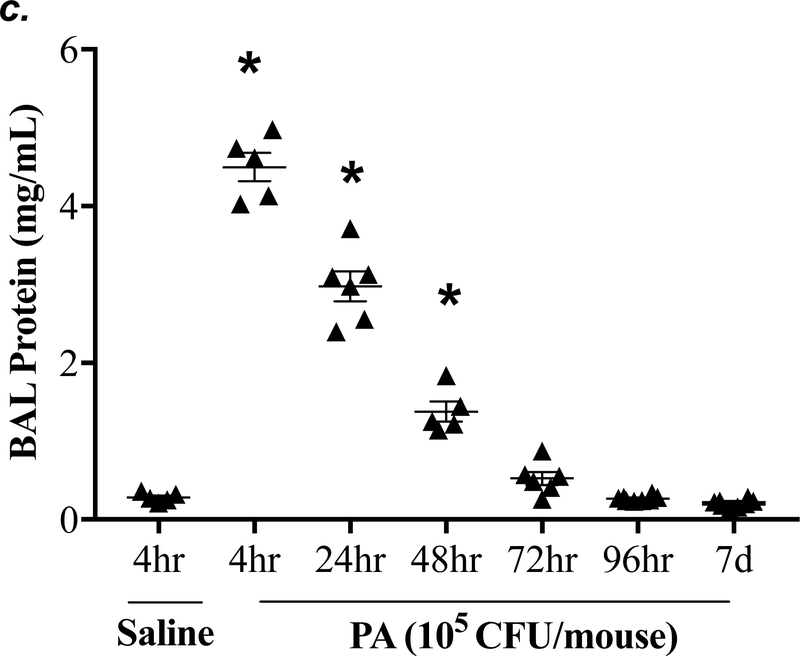

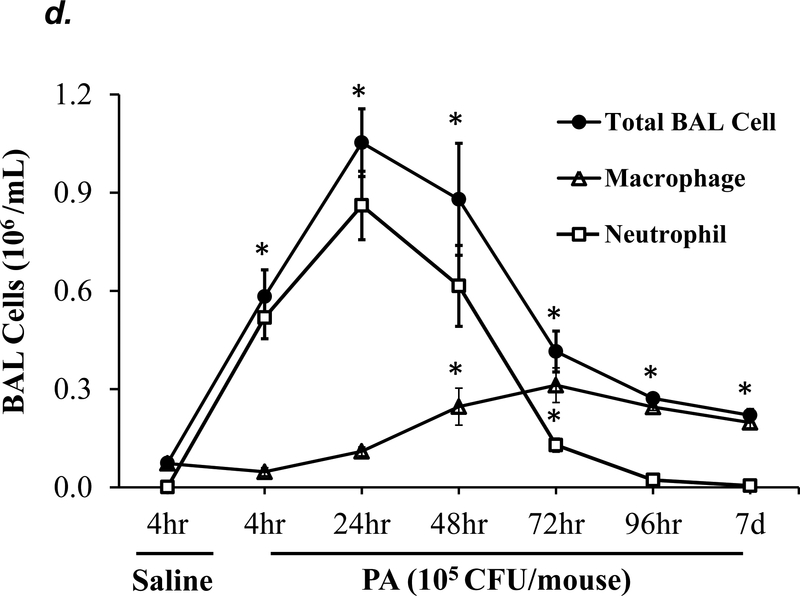

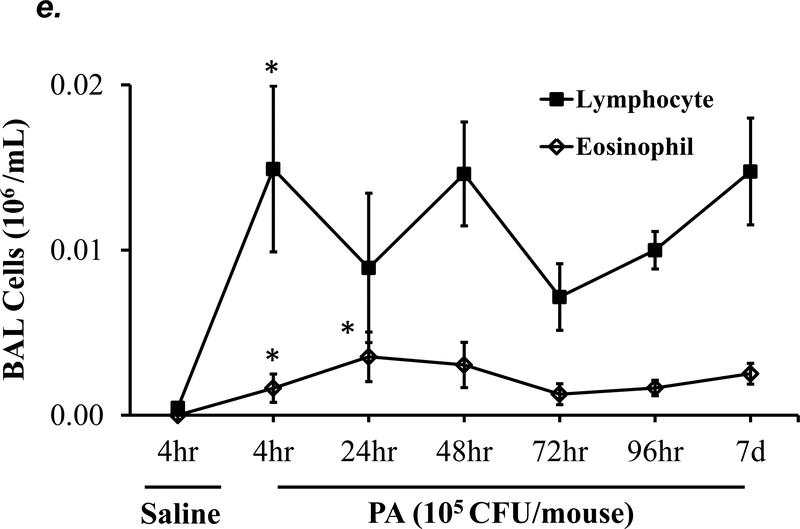

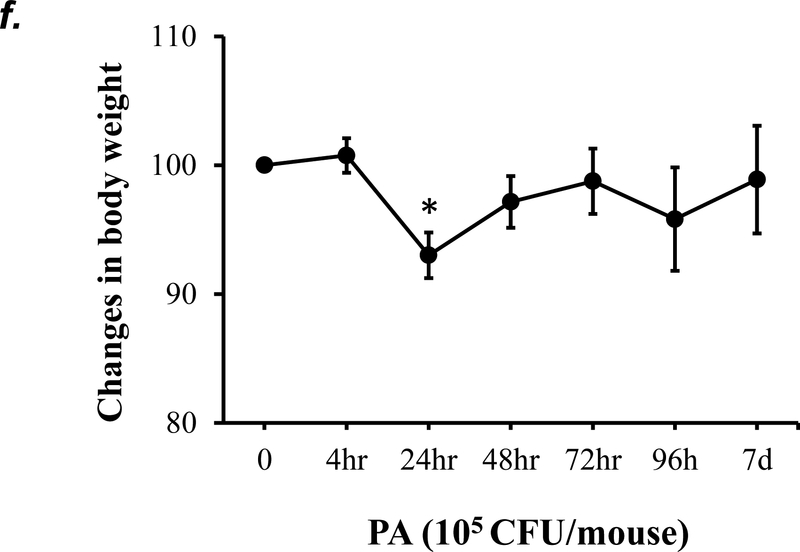

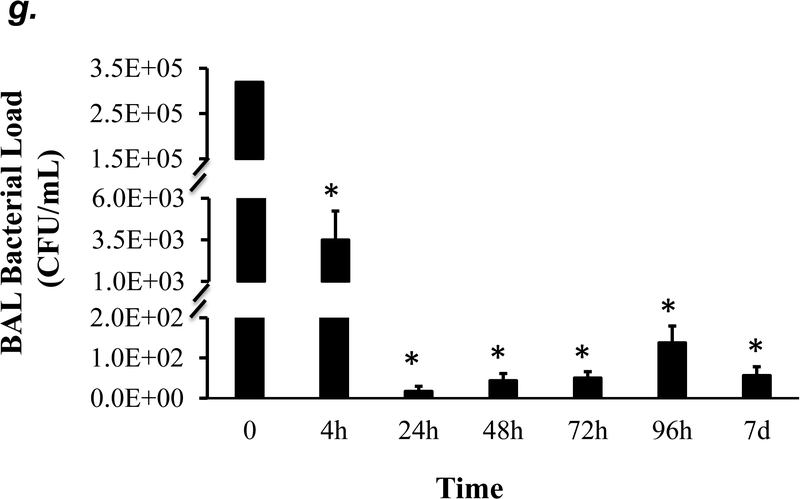

P. aeruginosa has been shown to cause acute lung injury in mice (38). To determine an optimal dose and time of P. aeruginosa (strain PA 103, hereinafter termed “PA”) that causes lung injury in C57BL/6 mice, we performed dose-response and time-course experiments. We found that PA at 1x103 - 4x105 CFU/mouse increased BAL protein content (Fig. 1a) and BAL total inflammatory cell counts (Fig. 1b) in a dose-dependent manner. Since 1x105 CFU/mouse of PA was the lowest dose of this bacteria which significantly increased both BAL protein content and total leukocyte counts, this dose of PA was used in subsequent experiments. We next assessed progression and resolution of lung injury following PA infection over a period of 7 days. We found that BAL protein content peaked at 4h, then slowly decreased, and completely resolved at 72h (Fig. 1c). Total BAL inflammatory cell counts peaked at 24h and slowly recovered between 48h-7days (Fig. 1d). In saline-challenged lungs (control), majority of BAL cells were macrophages, which slightly decreased at 4h, recovered at 24h, and progressively increased and became the dominant cell population again at 72h-7 days after PA infection (Fig 1d). It is noteworthy that the numbers of BAL macrophages at 72h-7 days post PA infection were significantly higher than control lungs (Fig. 1d) despite resolution of BAL protein levels (Fig. 1c). Neutrophils dominated BAL cell populations at 4h-48h after PA infection and then declined and returned to normal levels at 96h-7 days (Fig. 1d); effects associated with lung injury and resolution, respectively (Fig. 1c). Compared to the numbers of macrophages and neutrophils, the numbers of lymphocytes and eosinophils in BAL fluid were ~100 fold lower (Fig. 1e). PA infection mildly increased the numbers of lymphocytes and eosinophils in BAL at 4h-24h (Fig. 1e). Consistent with the time-course of lung injury, mice had a significant loss in body weight at 24h after PA infection and then slowly recovered (Fig. 1f). Bacteria in BAL were dramatically cleared at 4h and further reduced at 24h post PA infection (Fig. 1g). Interestingly, low levels of bacteria persisted in BAL fluid between 72h to 7 days (Fig. 1g) when BAL protein had completely resolved (Fig. 1c). This effect was associated with increased levels of BAL macrophages (Fig. 1d). These results suggest that low levels of bacteria were not able to perpetuate lung injury due to on-going alveolar macrophage activation.

Figure 1: PA caused acute lung injury in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

Panels a-b: Adult male C57BL/6 mice were administered with 1.0e3, 1.0e4, 1.0e5, or 4.0e5 CFU of PA103 (PA) or an equal volume of sterile saline (50 μl) by intratracheal (i.t.) instillation. 4h later, BAL protein levels (panel a) and BAL total inflammatory cell count (panel b) were assessed. 5–6 mice per group were used. Panels c-g: Adult male C57BL/6 mice were administered with 1.0e5 CFU of PA103 or equal volume of saline (50 μl) by intratracheal (i.t.) instillation. 4h, 24h, 48h, 72h, 96h, or 7 days later, BAL protein content (panel c), BAL inflammatory cell count (panels d-e), change in mouse body weight (panel f) and BAL bacterial load (panel g) were assessed. Data are presented as means ± SE. 5–8 mice per group were used. ANOVA and Fisher’s LSD post hoc test was used to determine statistical significance across groups. *P <0.05 versus control (saline for 4h).

Pharmacological inhibition of ENT1/2 prevented P. aeruginosa-induced lung edema and decline in lung function

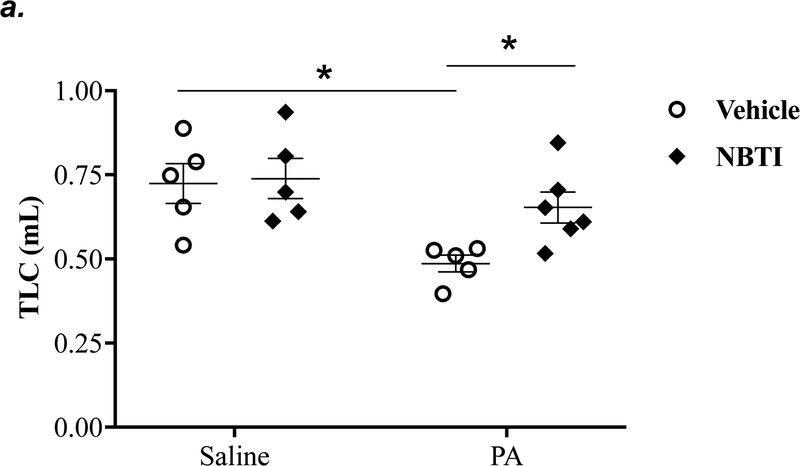

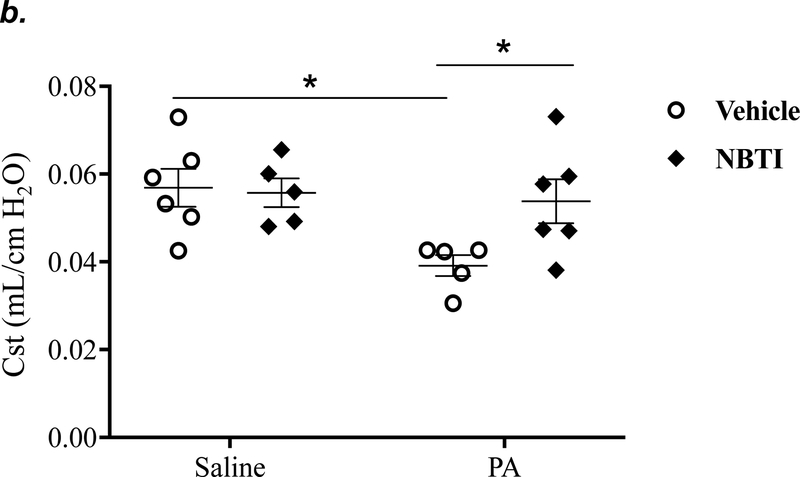

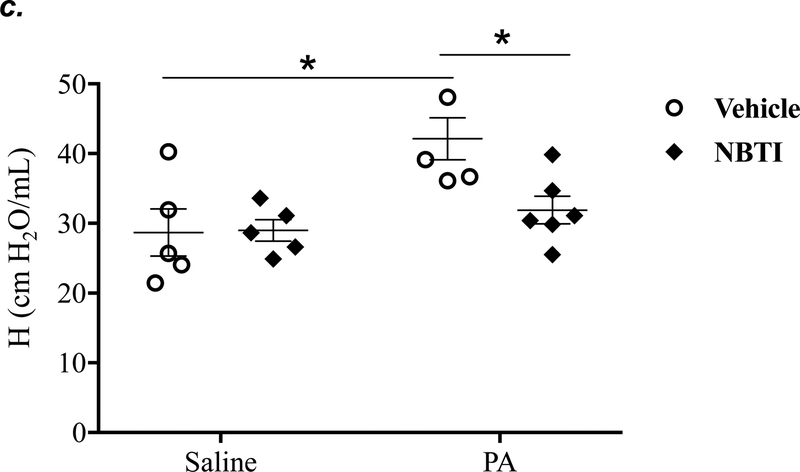

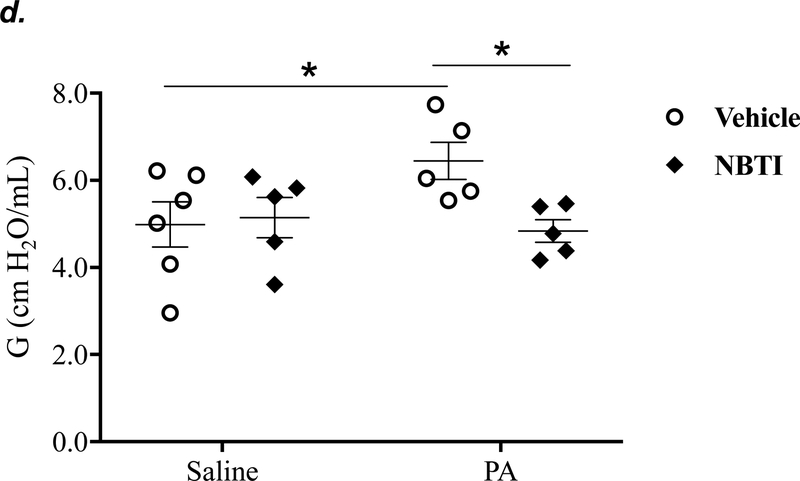

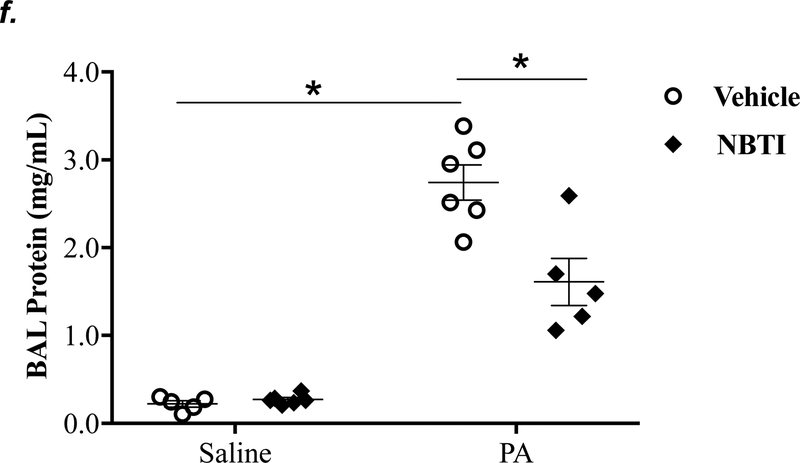

It is well known that acutely increased extracellular adenosine protects against acute lung injury (9–13). We have previously shown that sustained elevated adenosine increases endothelial barrier permeability and causes endothelial cell apoptosis via ENT1/2-facilitated intracellular adenosine uptake (21, 22). Endothelial cells have been reported to predominantly express ENT1 (24) or ENT2 (19). We hypothesized that blocking intracellular adenosine uptake by inhibition of ENT1/2 would simultaneously increase extracellular adenosine and would protect against PA-induced acute lung injury. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effect of ENT1/2 inhibitor, NBTI, on PA-induced changes in lung function and pulmonary edema. At 4h after intratracheal instillation of 1x105 CFU of PA, mice displayed typical lung edema characterized by decreased total lung capacity (TLC) (Fig. 2a), decreased static lung compliance (Cst) (Fig. 2b), increased parenchymal elastance (H) (Fig. 2c), and increased parenchymal resistance (H) (Fig. 2d). Pretreatment of mice with NBTI (2 mg/kg) completely prevented PA-induced decline in lung function (Fig. 2a–d). Similarly, PA infection significantly enhanced pulmonary edema, as assessed by lung wet-to-dry weight ratio (Fig. 2e) and BAL protein content (Fig. 2f). Pretreatment with NBTI prevented PA-induced pulmonary edema (Fig. 2e–f). These results indicate that inhibition of ENT1/2 protects against PA-induced acute lung injury.

Figure 2: Pharmacological inhibition of ENT1/2 abolished PA-induced lung edema and decline in lung function.

Adult male C57BL/6 mice were intraperitoneally injected with the ENT1/2 inhibitor, nitrobenzylthioinosine (NBTI; 2 mg/kg in DMSO-saline) or vehicle (DMSO-saline). After 30 minutes, mice were administered 1.0e5 CFU of PA or equal volume of saline by intratracheal (i.t.) instillation. After 4h, total lung capacity (TLC) (panel a), static lung compliance (Cst) (panel b), lung tissue elastance (H) (panel c), and lung tissue damping (G) (panel d) were assessed using the FlexiVent system. Lung wet-to-dry weight ratio was assessed (panel e). BAL protein content was assessed in other mice subjected to the same treatments (panel f). Data are presented as means ± SE, 5–6 mice per group were used unless otherwise indicated. ANOVA and Fisher’s LSD post hoc test was used to determine statistical significance among groups with *P <0.05 versus control.

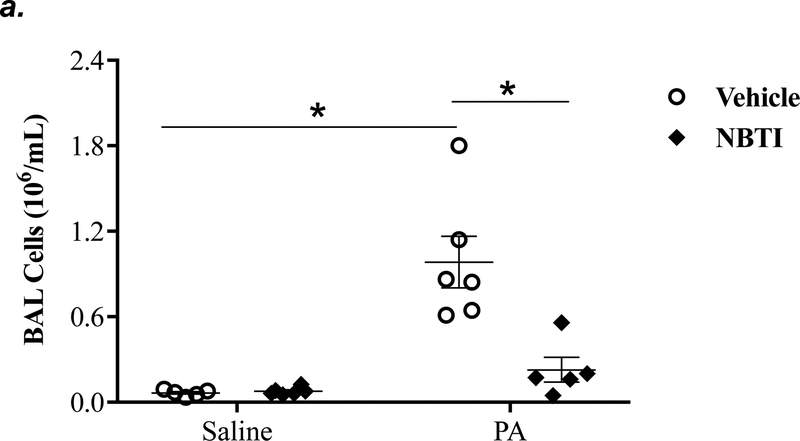

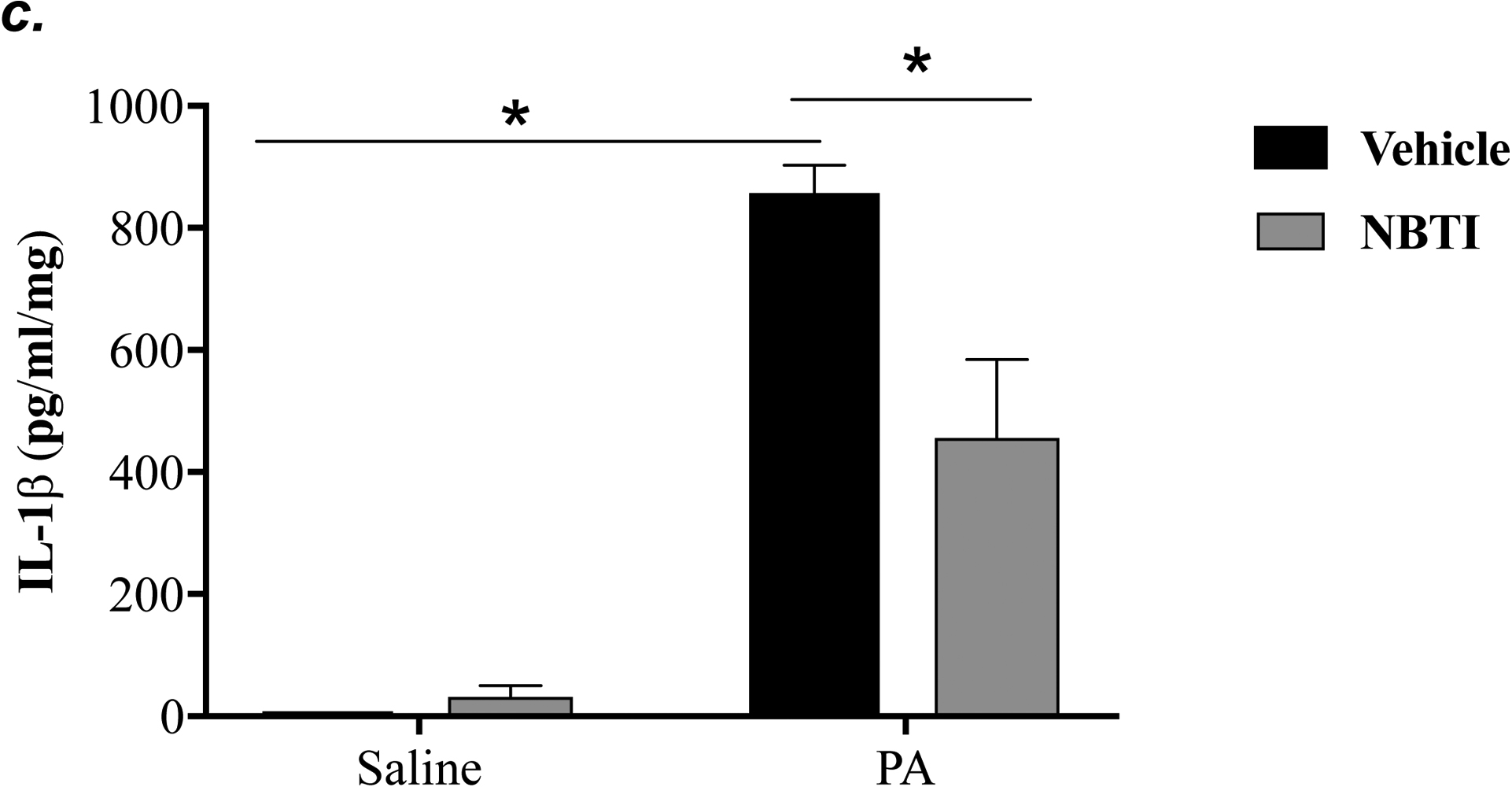

Pharmacological inhibition of ENT1/2 blunted P. aeruginosa-induced lung inflammation

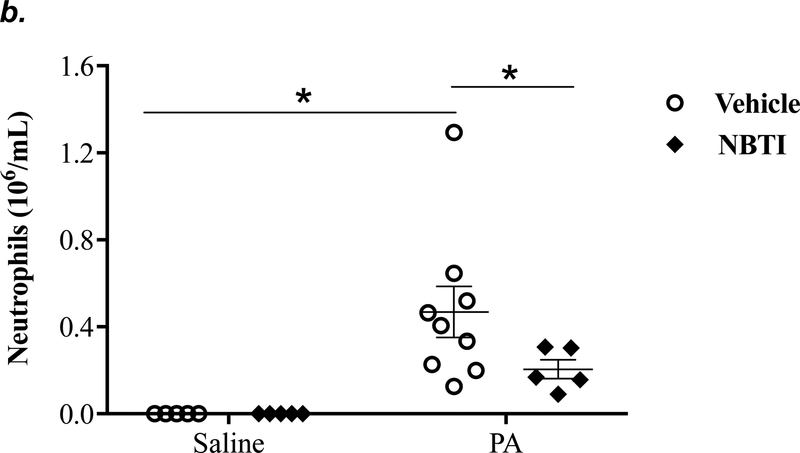

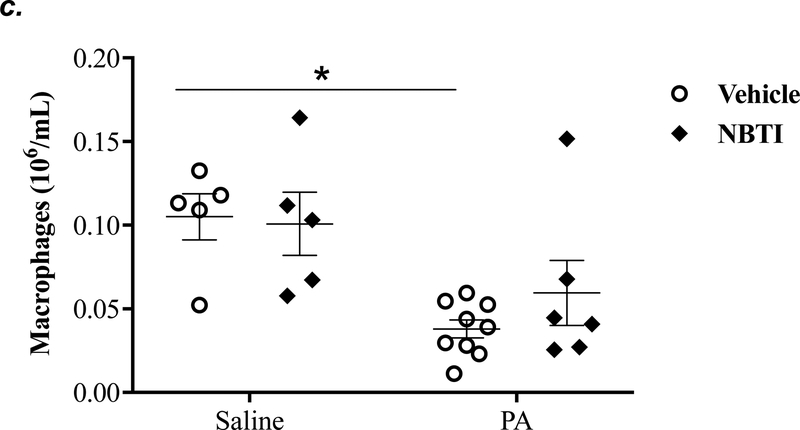

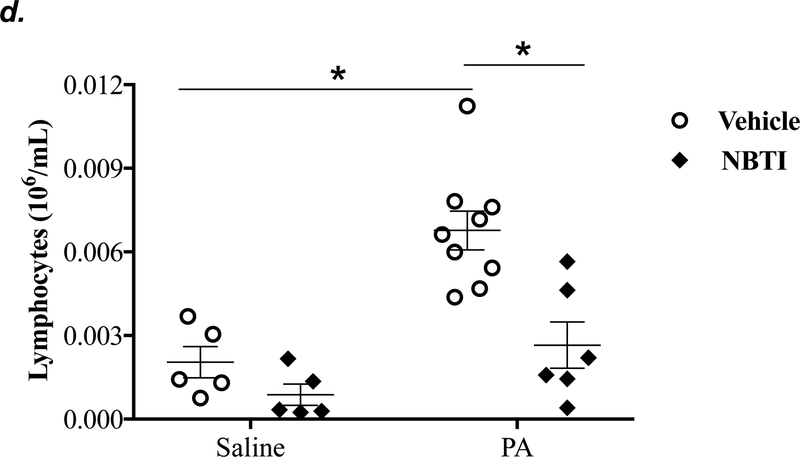

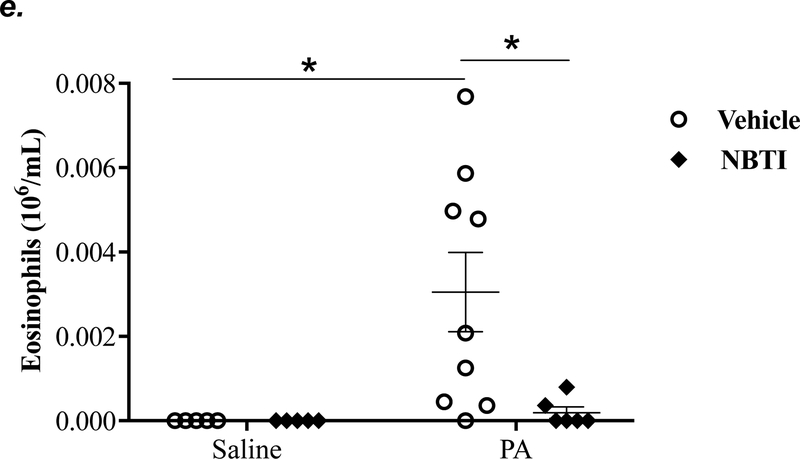

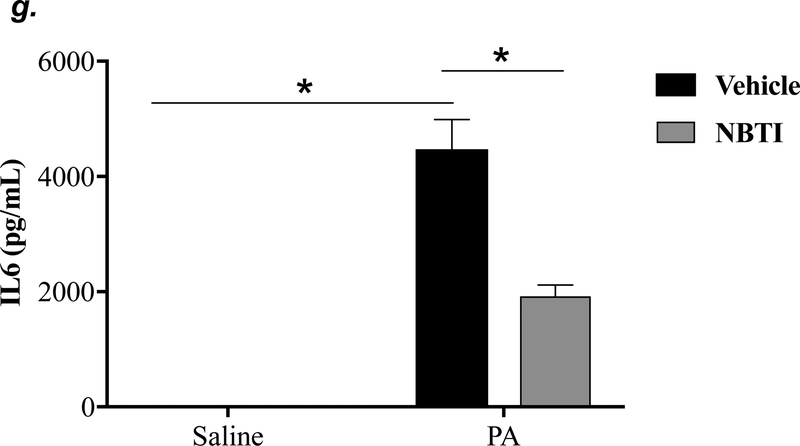

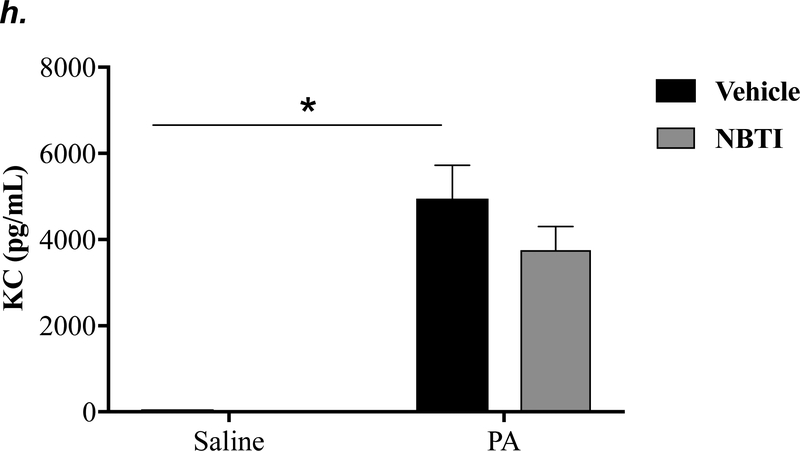

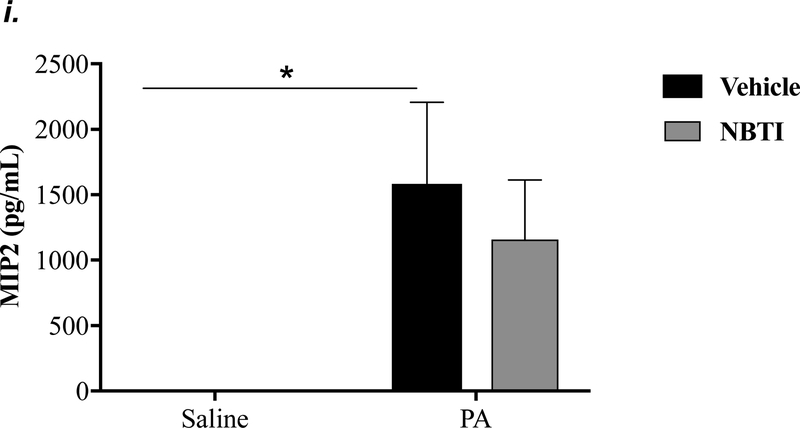

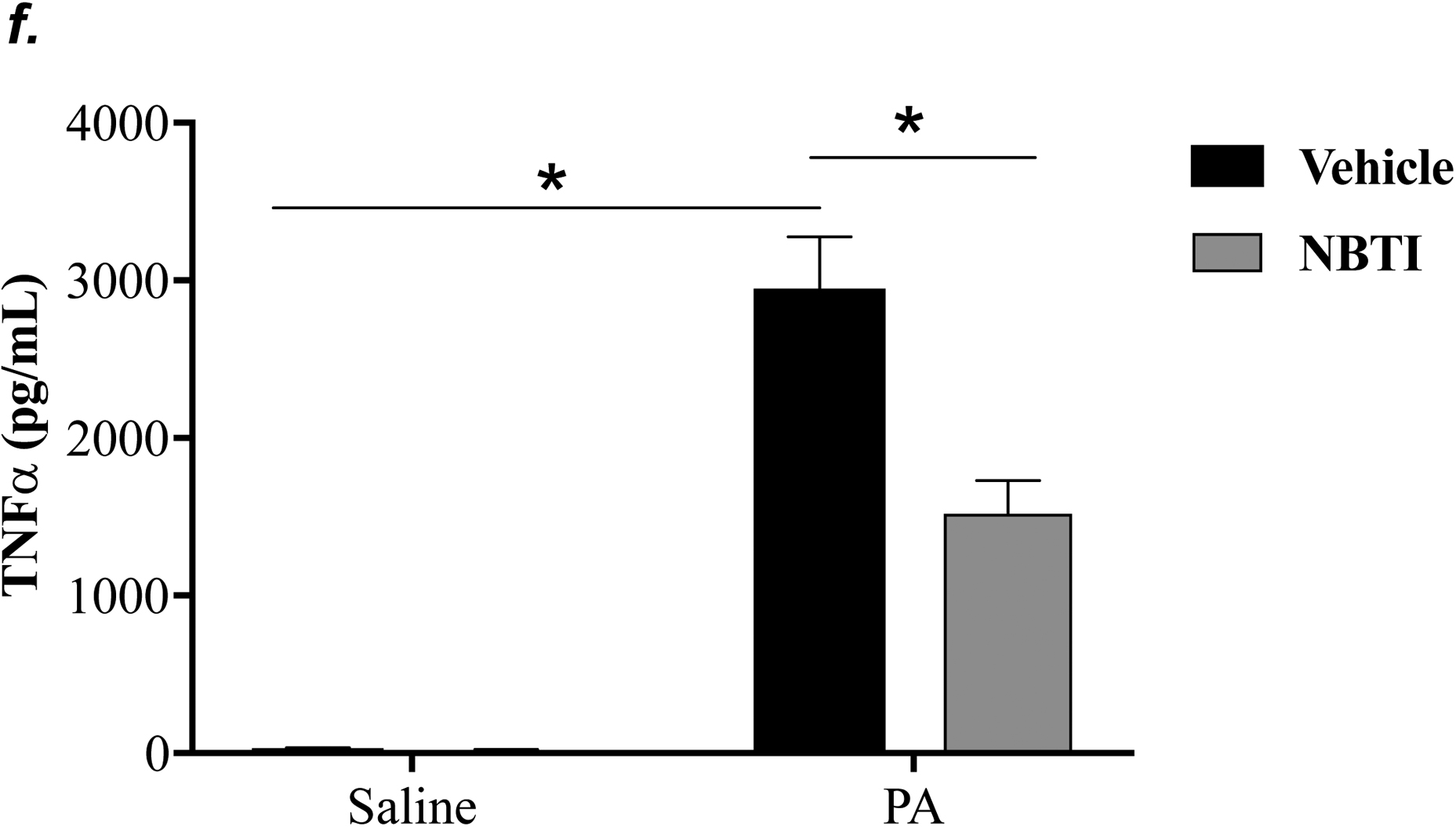

To determine the effect of pharmacological inhibition of ENT1/2 on PA-induced lung inflammation, we evaluated inflammatory cell infiltration, cytokine, and chemokine secretion into the BAL fluid of mice infected with PA for 4h. As expected, intratracheal administration of PA significantly increased the total number of inflammatory cells in the BAL (Fig. 3a). Pretreatment with NBTI reversed PA-induced increase in BAL inflammatory cells (Fig. 3a). NBTI blunted PA-induced increases in neutrophils (Fig. 3b) but had a marginal effect on macrophages (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, pretreatment with NBTI significantly reduced PA-induced increases in BAL lymphocytes and eosinophils (Fig. 3d–e). Consistently, NBTI also significantly blunted PA-induced release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-a (Fig. 3f) and IL-6 (Fig. 3g), with a trend toward protection against PA-induced increase in keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC) and MIP2 (Fig. 3h–i).

Figure 3: Pharmacological inhibition of ENT1/2 blunted PA-induced lung inflammation.

Adult male C57BL/6 mice were intraperitoneally administered NBTI (2 mg/kg in DMSO-saline) or vehicle (DMSO-saline). After 30 minutes, mice were administered 1.0e5 CFU of PA or equal volume of saline by intratracheal (i.t.) instillation. After 4h, BAL fluid was collected for assessment of total numbers of inflammatory cells (panel a) and numbers of inflammatory cells by subset (panels b-e) and protein levels of TNF-α (panel f), IL-6 (panel g), keratinocyte-derived chemokines (KC) (panel h) and MIP2 (panel i). Data are presented as means ± SE. 5–9 mice per group were used (panels a-e). n = 4–5 mice per group in ELISA experiments (panels f-i), which were performed in triplicate for each biological sample. ANOVA and Fisher’s LSD post hoc test was used to determine statistical significance among groups, with *P <0.05 versus all groups shown.

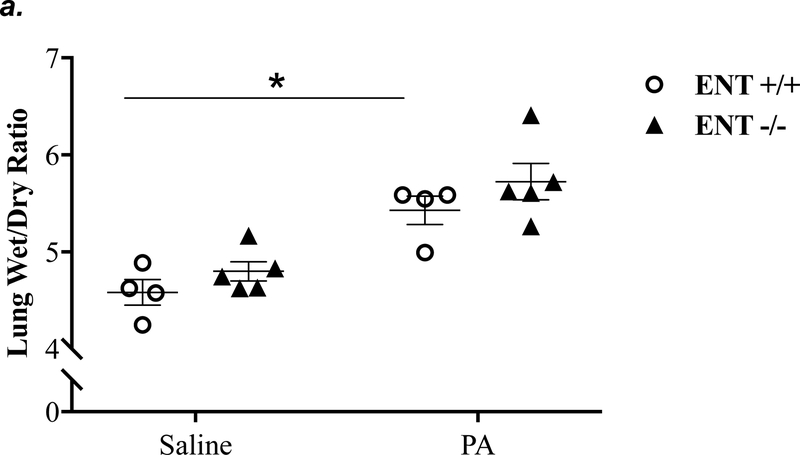

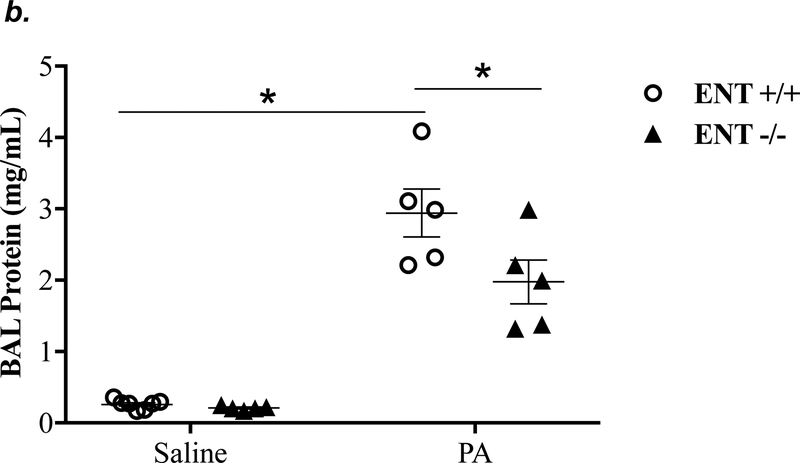

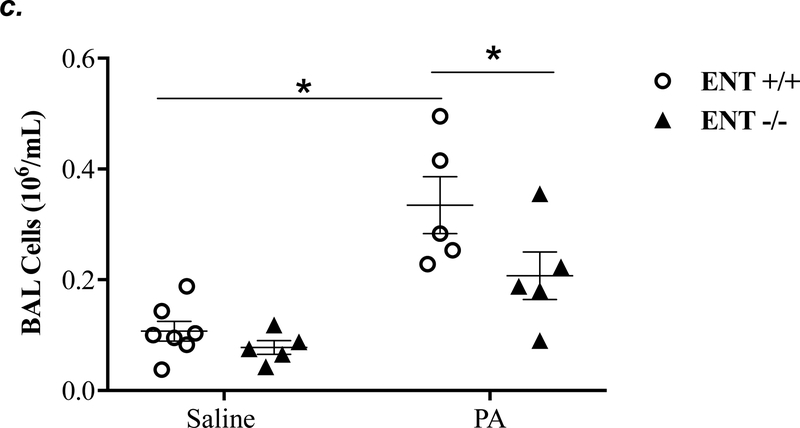

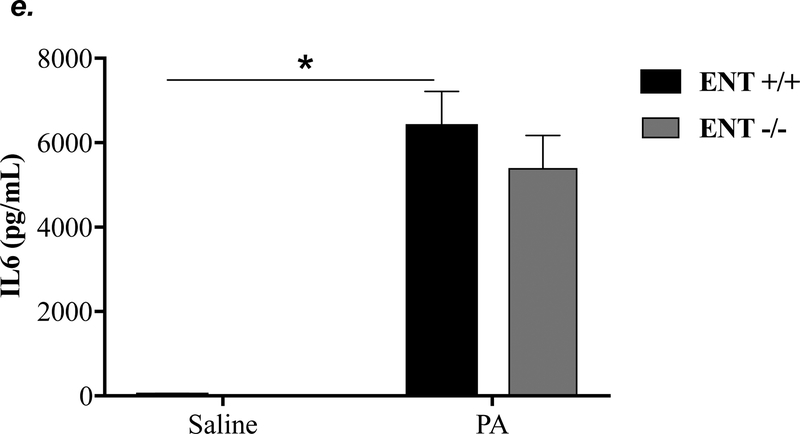

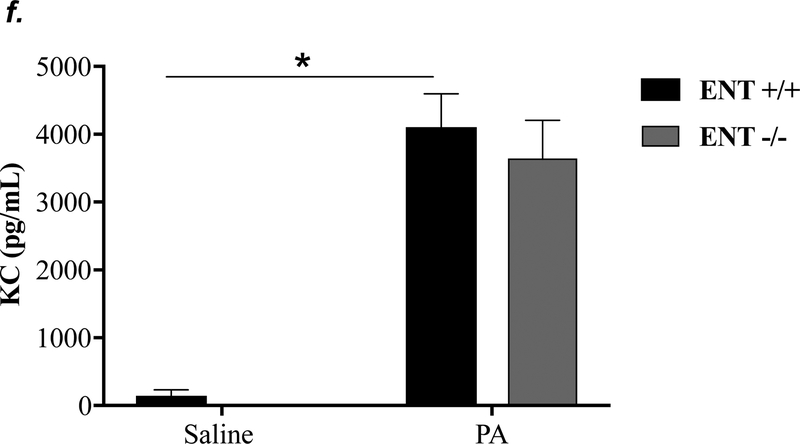

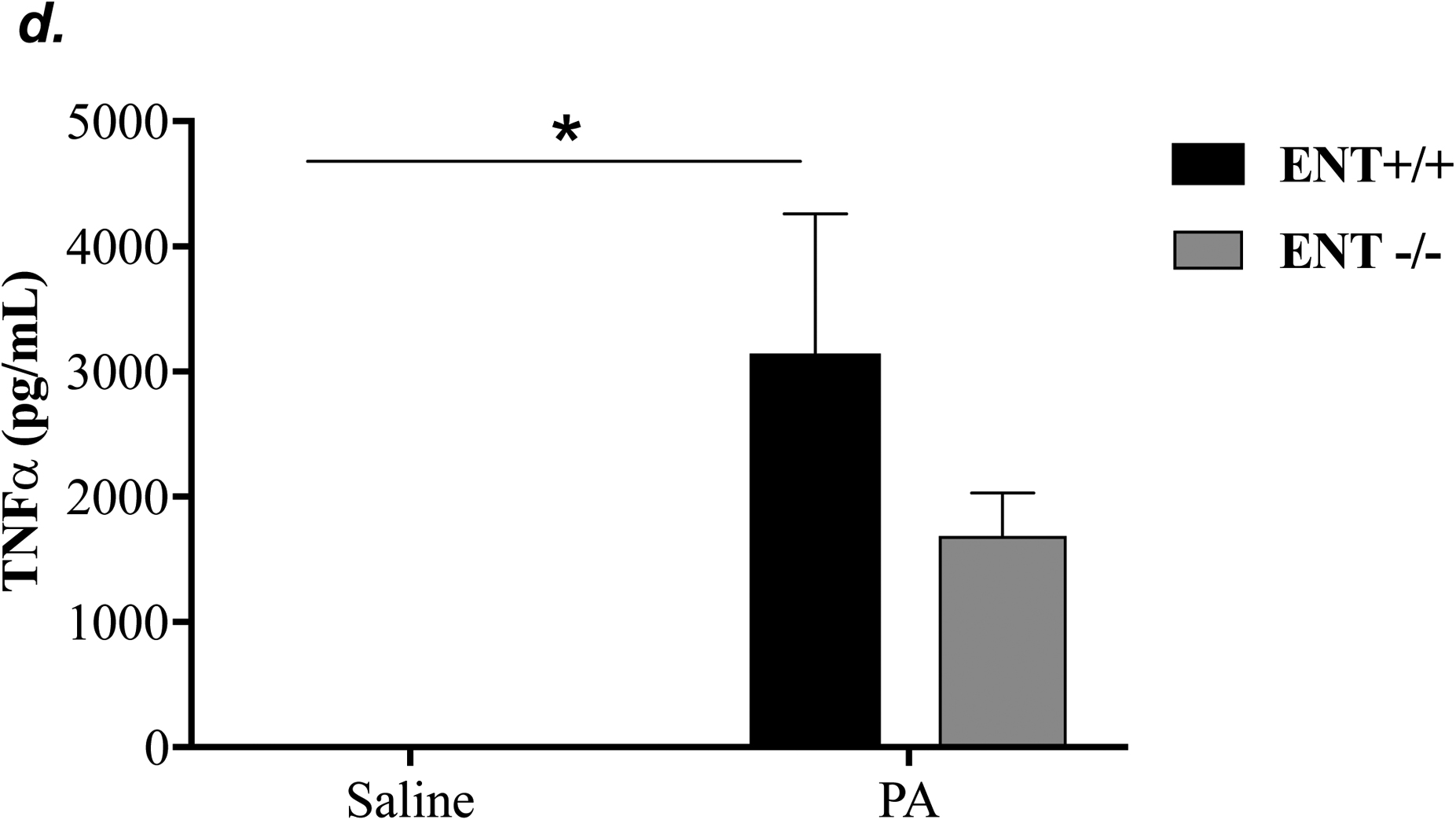

ENT1 knockout partially attenuated P. aeruginosa -induced lung edema and inflammation

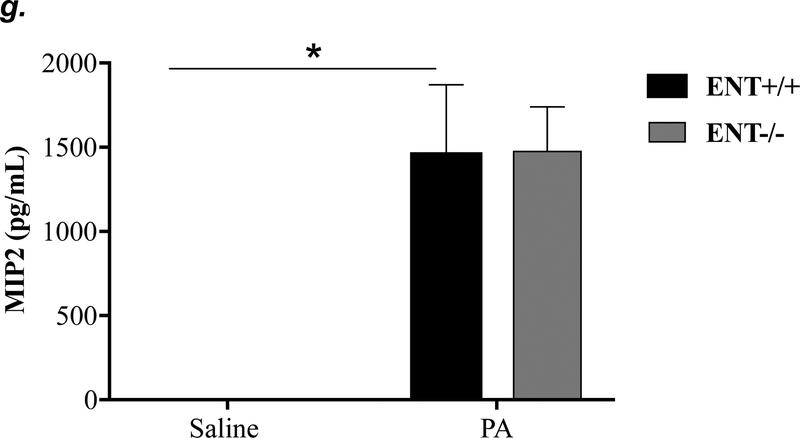

ENT1 has a 2.8-fold higher affinity for adenosine than ENT2 (39). ENT1 is the predominant transporter for adenosine uptake in human microvascular endothelial cells (23). NBTI is 7000-fold more effective in inhibiting ENT1 than ENT2 (39). Thus, we hypothesized that inhibition of ENT1 was responsible for NBTI protection against PA-induced acute lung injury. To specifically determine the role of ENT1 in PA-induced acute lung injury, we used global ENT1 null mice. As expected, PA infection for 4h caused acute lung injury in wild type control mice, as indicated by increased lung wet-to-dry weight ratio (Fig. 4a), increased BAL protein content (Fig. 4b), and elevated BAL inflammatory cell counts (Fig. 4c). PA-induced increase in BAL protein content and inflammatory cell count were significantly attenuated in ENT1 null mice (Fig. 4b–c). However, PA-induced increase in lung wet-to-dry weight ratio was not altered by ENT1 knockout (Fig. 4a). Similarly, global ENT1 knockout had minor effects on PA-induced release of TNF-α (Fig. 4d), IL-6 (Fig. 4e), KC (Fig. 4f) and MIP2 (Fig. 4g). Taken together, our results suggest that inhibition of both ENT1 and ENT2 may contribute to NBTI protection against PA-induced acute lung injury.

Figure 4: ENT1 knockout partially protected against PA-induced acute lung injury.

ENT1 null mice (C57/BL6 genetic background) and age- and sex-matched wild type control littermates were administered with 1.0e5 CFU of PA 103 (PA) or equal volume of saline by intratracheal (i.t.) instillation. After 4h, lung wet-to-dry weight ratio was assessed (panel a). BAL protein content (panel b) and BAL inflammatory cell count (panel c) were assessed in separate mice subjected to the same treatments. Data are presented as means ± SE. n = 4–7 mice per group. BAL fluid was also prepared for assessment of levels of TNF-α (panel d), IL-6 (panel e), KC (panel f), and MIP2 (panel g). Data are presented as means ± SE with n = 4–6 mice per group for ELISA experiments that were performed in triplicate for each biological sample. ANOVA and Fisher’s LSD post hoc test was used to determine statistical significance among groups with *P <0.05 versus all groups shown.

A2AR and A2BR mediated the protective effect of ENT1/2 inhibition against P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury

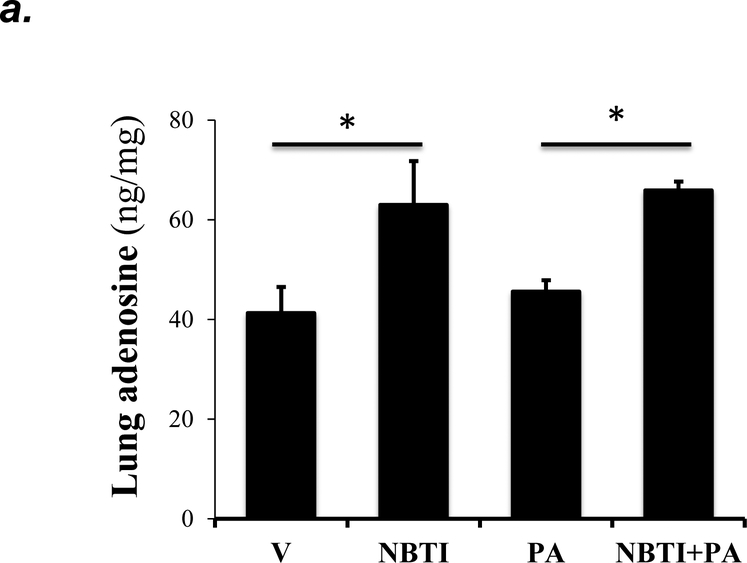

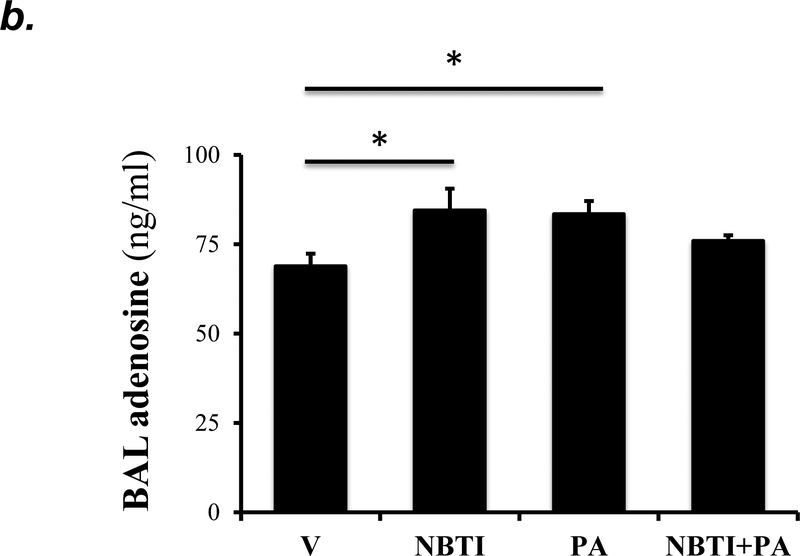

To address whether the ENT1/2 inhibitor, NBTI, protects against PA-induced acute lung injury by adenosine-mediated activation of adenosine receptors, we first assessed the effect of NBTI on adenosine levels in lung tissue and BAL fluid. We found that both NBTI alone and pretreatment with NBTI prior to PA administration significantly increased lung adenosine levels (Fig. 5a). NBTI and PA infection also increased extracellular adenosine levels in BAL (Fig. 5b).

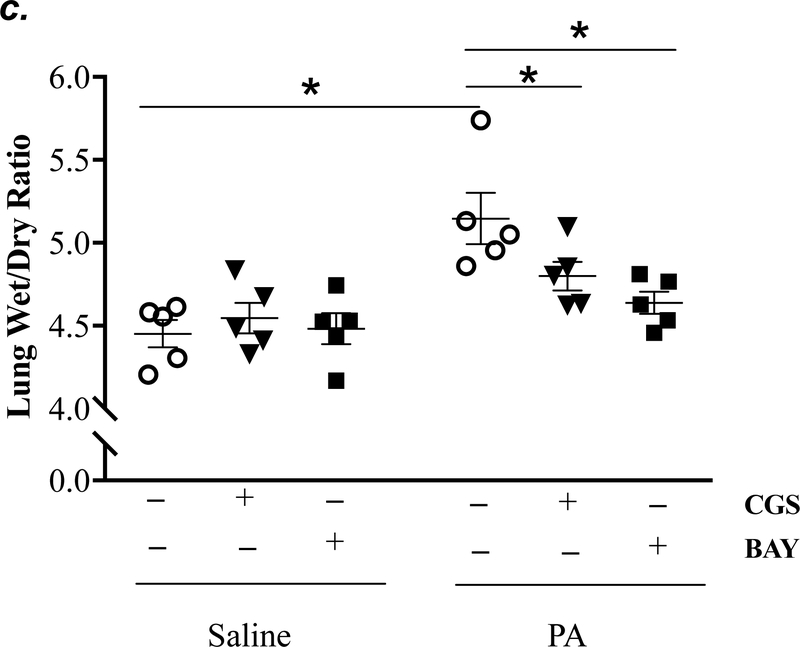

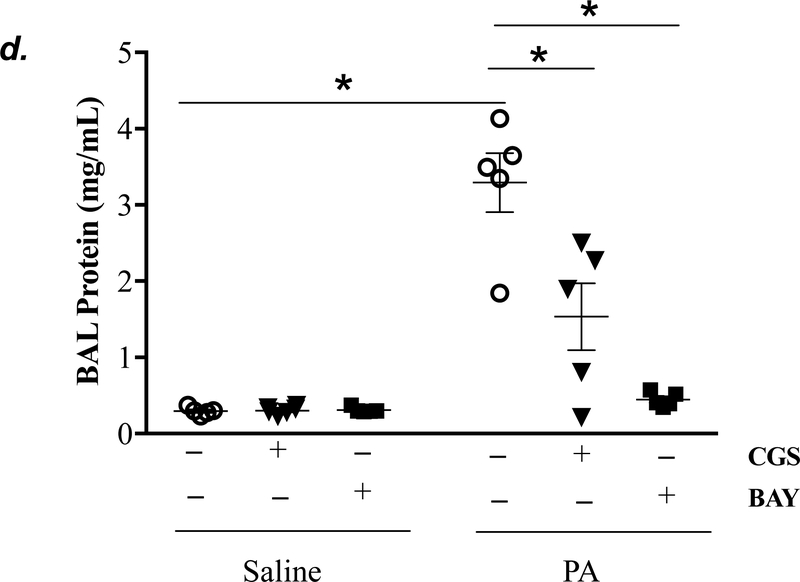

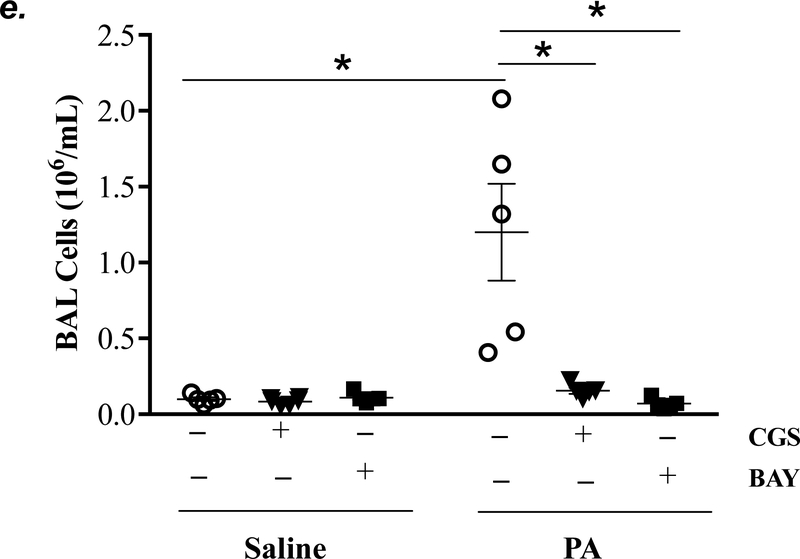

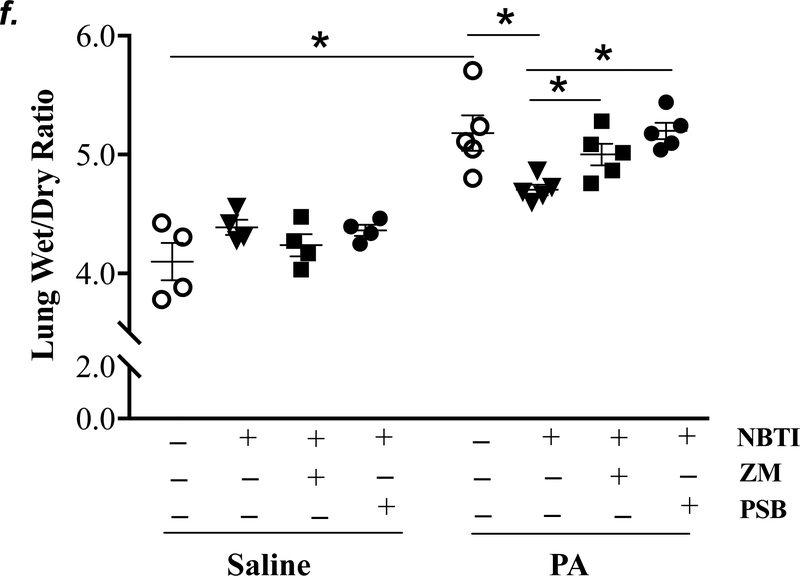

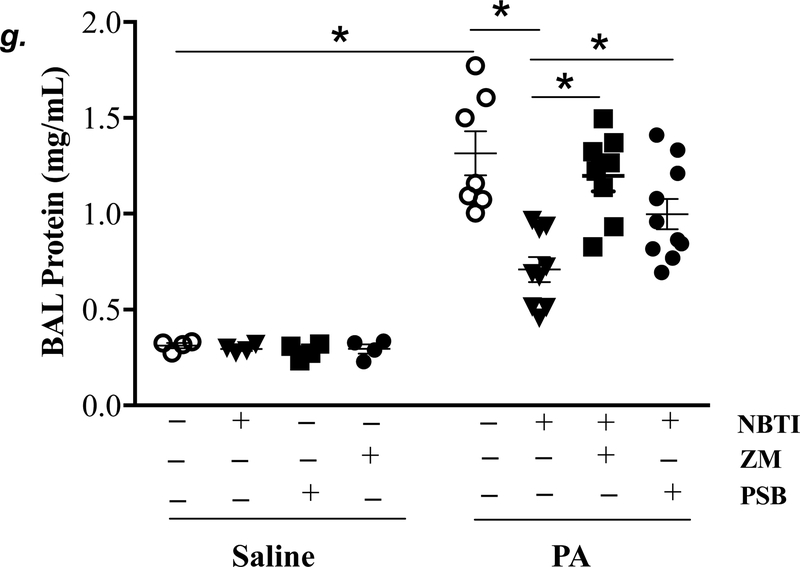

Figure 5: A2AR and A2BR mediated the protection of NBTI against PA-induced acute lung injury.

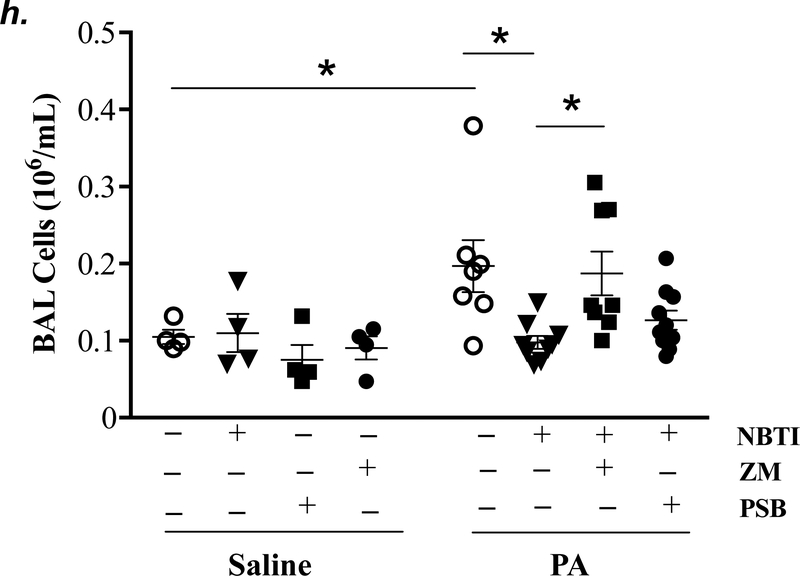

Adult male C57BL/6 mice were intraperitoneally administered NBTI (2 mg/kg) or vehicle. After 30 minutes, mice were administered 1.0e5 CFU of PA or equal volume of saline by intratracheal (i.t.) instillation. Lung tissue and BAL fluid were collected for assessment of adenosine levels by HPLC (panels a-b). Data are presented as means ± SE, with n = 4–5 mice per group. Panels c-e: Adult male C57BL/6 mice were intraperitoneally administered the A2AR receptor agonist, CGS21680 (CGS; 0.2 mg/kg in DMSO-saline), the A2BR agonist, BAY60–6583 (BAY; 10 mg/kg in DMSO-saline), or vehicle (DMSO-saline). After 30 minutes, mice were administered 1.0e5 CFU of PA or equal volume of saline by intratracheal (i.t.) instillation. After 4h, lung wet/dry weight ratio was assessed (panel c). BAL protein levels (panel d) and BAL total inflammatory cell count (panel e) were assessed in other mice subjected to the same treatments. Data are presented as means ± SE, with n = 5–6 mice per group. Panels f-h: Adult male C57BL/6 mice were intraperitoneally administered NBTI (2 mg/kg in DMSO-saline) alone or in combination with A2AR antagonist, ZM 241385 (ZM; 10 mg/kg in DMSO-saline) or the A2BR antagonist, PSB 1115 (PSB; 10 mg/kg in DMSO-saline). After 30 minutes, mice were administered 1.0e5 CFU of PA or equal volume of saline by intratracheal (i.t.) instillation. After 4h, lung wet/dry weight ratio was assessed (panel f). BAL protein levels (panel g) and BAL total inflammatory cell count (panel h) were assessed in other mice subjected to the same treatments. Data are presented as means ± SE, n = 4–10 mice per group. ANOVA and Fisher’s LSD post hoc test was used to determine statistical significance across groups with *P <0.05 versus all groups shown.

Acute activation of adenosine receptors A2AR and A2BR protects against acute lung injury (12, 13, 17, 42, 43). To determine if activation of A2AR and A2BR mimics NBTI protecting against PA-induced acute lung injury, mice were pretreated with a highly selective A2AR agonist, CGS21680, or a highly selective A2BR agonist, BAY60–6583. As expected, PA increased lung wet/dry weight ratio (Fig. 5c), BAL protein content (Fig. 5d), and BAL cell counts (Fig. 5e). Pretreatment of mice with either CGS21680 or BAY60–6583 significantly blunted PA-induced increases in lung wet/dry weight ratio (Fig. 5c), BAL protein content (Fig. 5d), and BAL cell counts (Fig. 5e).

We next assessed the role of A2AR and A2BR in mediating the protection of NBTI against PA-induced acute lung injury. As expected, 4h after PA infection, lung wet/dry weight ratio, BAL protein content, and BAL total cell count were significantly increased; effects that were attenuated by pretreatment with NBTI (Fig. 5f–h). However, pretreatment of mice with NBTI in combination with a highly selective A2AR antagonist, ZM241385, or a highly selective A2BR antagonist, PSB1115, resulted in a significant loss in the protective effect of NBTI (Fig. 5f–h). These results suggest that inhibition of ENT1/2 by NBTI protects against PA-induced acute lung injury by extracellular adenosine-dependent activation of A2AR and A2BR.

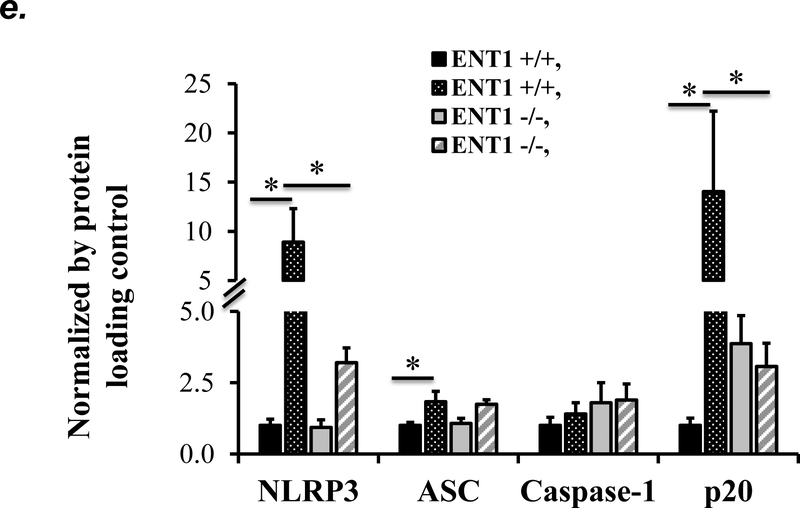

ENT1 blockade protected against P. aeruginosa- induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation

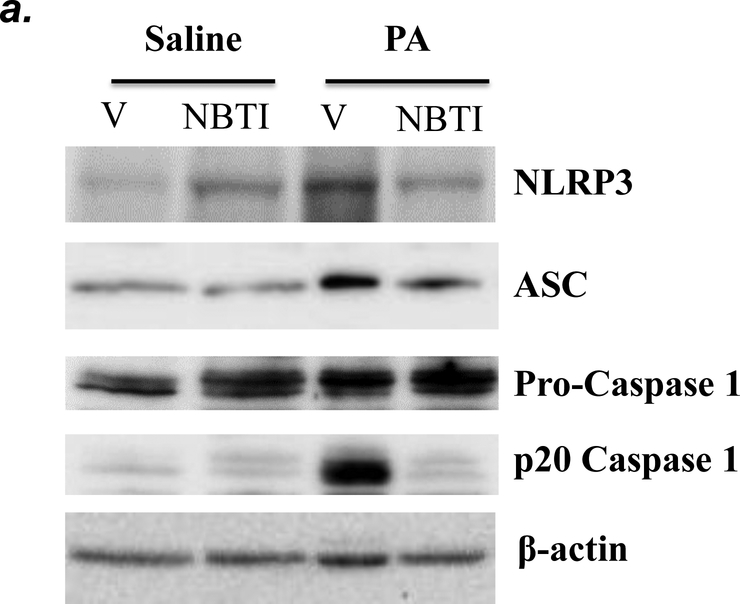

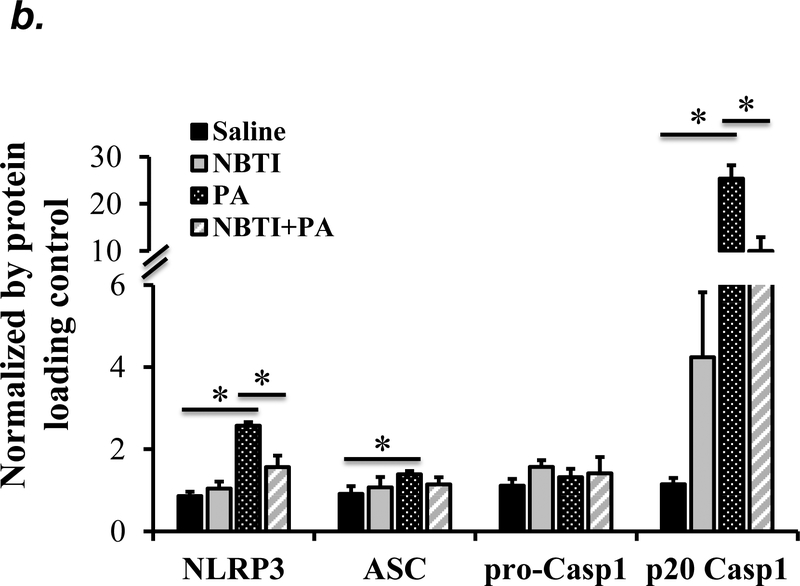

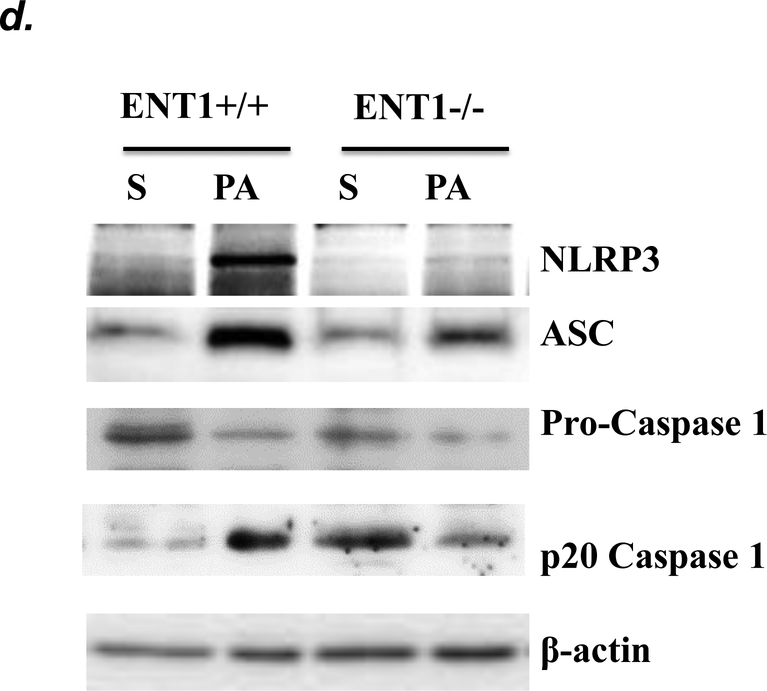

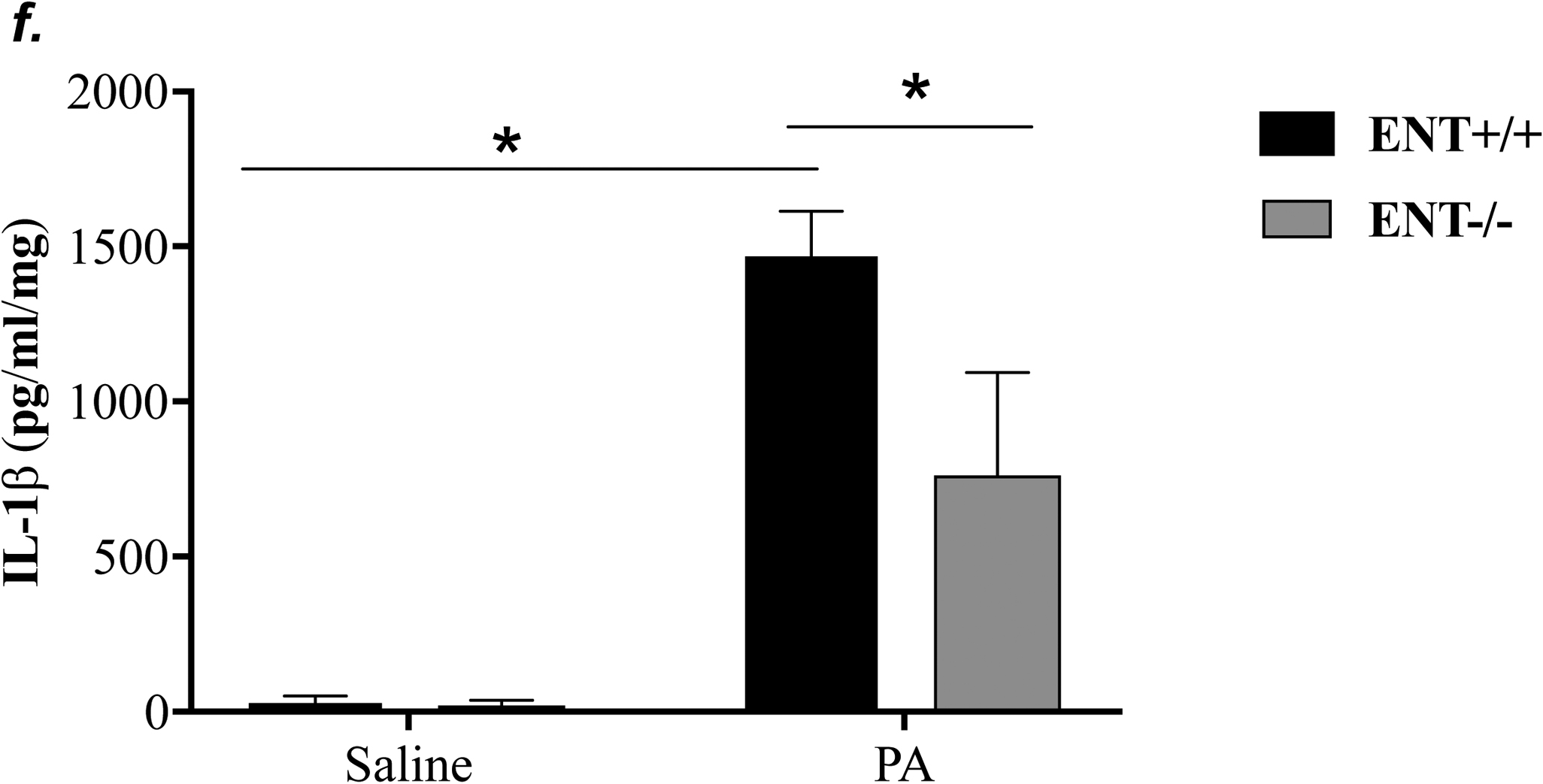

NLRP3 inflammasome activation has been implicated in several animal models of acute lung injury induced by LPS (28), sepsis (29), mechanical ventilation (27), hyperoxia (30), and hemorrhagic shock (31). In this study, we found that PA activated NLRP3 inflammasome, as indicated by elevation of NLRP3, ASC and IL-1β protein levels and caspase-1 activation (Fig. 6a–c). To address whether ENT1 inhibition protects against PA-induced acute lung injury via suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome activation, we assessed the effects of ENT1 blockade on PA-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation. We found that PA-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation was dramatically attenuated by NBTI (Fig 6a–c). Consistently, PA-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in wild type mice was not observed in ENT1 null mice (Fig. 6d–f). These results support the concept that ENT1 blockade protects against PA-induced acute lung injury via inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome.

Figure 6: Blockade of ENT1 protected against PA-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Adult male C57BL/6 mice were intraperitoneally administered NBTI (2 mg/kg in DMSO-saline) or vehicle (DMSO-saline). ENT1 null mice and age-/sex-matched wild type control littermates were administered 1.0e5 CFU of PA103 or equal volume of saline by intratracheal (i.t.) instillation. Lung NLRP3 inflammasome activation was assessed by protein levels of NLRP3, ASC, pro-caspase-1, active (p20) caspase-1 (panels a-b, d-e) and IL-1β (panels c, f). β-actin was used as protein loading control. Representative images are shown in Panels a, d. Densitometry data (panels b, e) are presented as the means ± SE of protein of interested relative to protein loading control. n=4–6 mice were used per group. ANOVA and Fisher’s LSD post hoc test were used to determine statistical significance among groups, with *P <0.05 versus all groups shown.

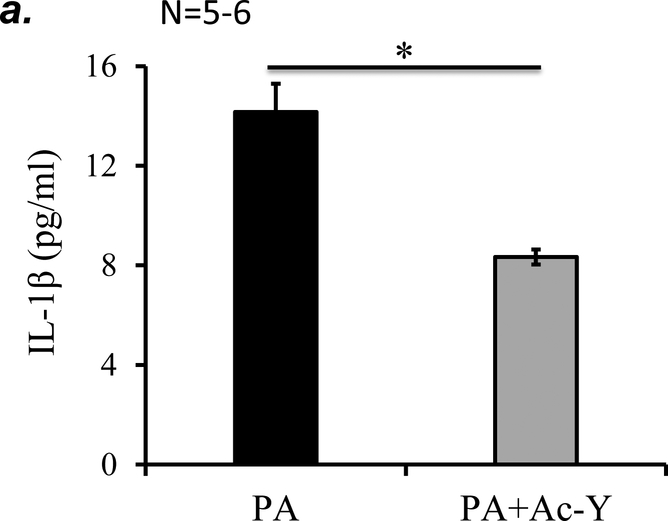

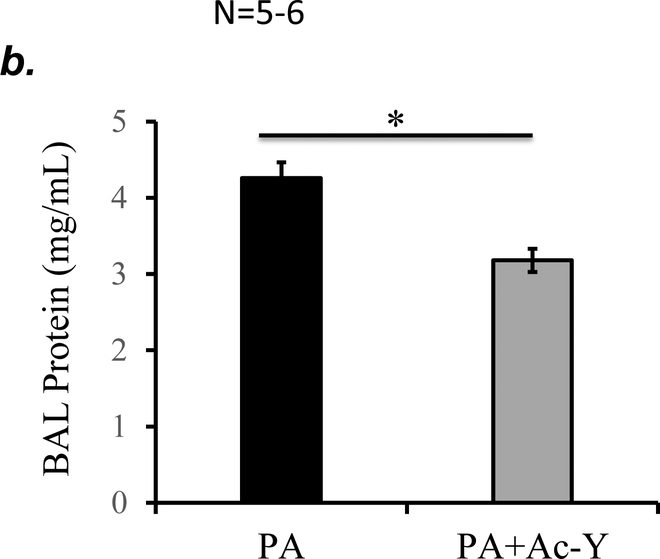

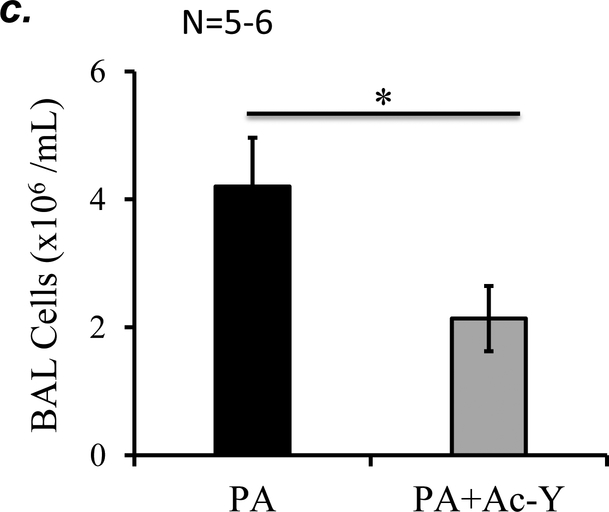

Inhibition of inflammasome protected against PA-induced acute lung injury

To further determine if inflammasome activation plays a role in PA-induced acute lung injury, we tested the effect of inflammasome inhibition using caspase-1 inhibitor, Ac-YVAD-cmk on PA-induced acute lung injury. We confirmed that 10 mg/kg of Ac-YVAD-cmk partially inhibited PA-induced inflammasome activation, as assessed by mature (active) IL-1β in BAL (Fig. 7a). This dose of Ac-YVAD-cmk significantly attenuated PA-induced increase in BAL protein content and inflammatory cells (Fig. 7b–c). Taken together, our results suggest that NLRP3 inflammasome activation plays a critical role in PA-induced acute lung injury.

Figure 7. Inhibition of inflammasome protected against PA-induced acute lung injury.

Adult male C57BL/6 mice were intraperitoneally administered with caspase-1 inhibitor, Ac-YVAD-cmk (Ac-Y) at a dose of 10 mg/kg or same volume of vehicle (DMSO-saline) as a control. One hour later, mice were given 7x105 CFU of PA103 in 50 μl saline by intratracheal instillation. 18h after administration of PA103, BAL fluid was collected for assessment of inflammasome activation by measuring IL-1β levels in cell free BAL fluid (a), BAL total protein levels (b), and BAL total inflammatory cells (c). 5–6 mice per experimental group were used. Student’s T test were used to determine statistical difference between groups. * p<0.05.

Discussion

P. aeruginosa infection is one of the leading causes of hospital-acquired pneumonia associated with high morbidity and mortality worldwide. New therapeutics are needed due to growing prevalence of multidrug resistance. In this study, we found that either ENT1/2 pharmacological inhibition or ENT1 knockout protected against P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury in mice; an effect mediated by adenosine-dependent activation of A2AR and A2BR. ENT1 inhibition and knockout also prevented P. aeruginosa-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation. These results suggest that ENT1/2 blockade and NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition may be novel strategies to prevent and possibly treat P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury.

A laboratory strain of P. aeruginosa, PA103, was used in this study. Intra-tracheal instillation of PA103 dose-dependently produced a consistent, quantifiable, and reproducible lung injury with an effective dose of 105 CFU per mouse. In addition, intra-tracheal instillation of 1x105 CFU of PA103 per mouse caused consistently reproducible lung injury in a time-dependent manner, with a peak of lung edema at 4h and a peak of lung neutrophil infiltration and a small increase in eosinophils and lymphocytes at 24h. We also observed an initial decrease and a later increase in alveolar macrophages. PA103 infection also induced cytokines/chemokines including TNFα, IL6, KC and MIP-2 (mouse analogues of IL8). Although most bacteria were cleared from the lung by 24h after infection, bacteria were not completely eradicated by day 7. Our data indicate that PA103-induced mouse lung injury recapitulates many aspects of human P. aeruginosa pneumonia (44). Thus we believe that PA103 infection is a clinically relevant and reproducible model of pneumonia. Future studies are needed to confirm our observations with clinical isolates from patients with P. aeruginosa pneumonia.

In this study, we found that P. aeruginosa infection caused 500–1000 fold increases in lung neutrophils and 2–4 fold increases in lung eosinophils. While the role of neutrophils in response to infection is well documented, eosinophils play a more complicated roles in health and diseases (45). For example, eosinophils can serve as a part of innate host defense by targeting parasites and P. aeruginosa (46). Eosinopenia has been reported as a reliable marker for infection and low eosinophil count has been associated with severity of infection (45). Eosinophils are also key regulators of tissue remodeling/repair via Th2 immune responses. In addition, eosinophils can mediate allergen-induced pulmonary inflammation and tissue damage in asthmatic patients. Increased neutrophils and eosinophils both contribute to progressive pulmonary destruction in cystic fibrosis associated with P. aeruginosa infection (47). The increase in lung eosinophils in response to P. aeruginosa infection could be a part of innate host defense response or could contribute to pathogenesis. Interestingly, P. aeruginosa-induced increases in both neutrophils and eosinophils were prevented by NBTI. This effect was associated with protection against acute lung injury. Our results suggest that excessive infiltration of neutrophils and eosinophils to the lungs may contribute to P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury.

Extracellular adenosine is produced from ATP/ADP by actions of CD39 and CD73 (48). Extracellular adenosine signals via four distinct G protein-coupled adenosine receptors. Extracellular adenosine is metabolized by extracellular adenosine deaminase (ADA) and removed by intracellular uptake via adenosine transporter ENT1/2 (49). Upon uptake, intracellular adenosine is metabolized by intracellular ADA or phosphorylated by adenosine kinase into AMP and ATP. Extracellular adenosine signaling is elevated in several animal models of acute lung injury and this increase has been suggested as a compensatory mechanism for resolution of tissue injury (19, 20, 23). For example, ENT1 and ENT2 expression is diminished by acute hypoxia (23) and proinflammatory cytokines (IL6, TNFα, IL-1β) (19) in cultured endothelial and epithelial cells. Expression of ENT1, ENT2, and adenosine kinase is also repressed in lungs acutely injured by high-pressure mechanical ventilation (20), LPS (19), and hypoxia (23). In addition, expression of CD39, CD73, and A2BR is induced in lungs acutely injured by hypoxia (48) and LPS (20). LPS also binds to and activates A1R in endothelial cells (50). In this study, we show that P. aeruginosa infection significantly increased adenosine levels in BAL fluid. Whether P. aeruginosa infection affects expression and/or activities of ENT1/2, CD39, CD73, adenosine kinase, adenosine deaminase and adenosine receptors remain to be determined.

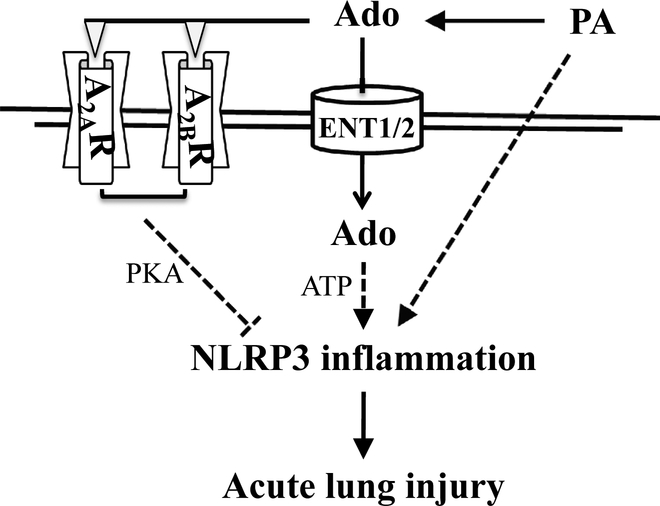

We and others have previously shown that acutely increased extracellular adenosine protects against lung injury via activation of adenosine receptors, A2AR and A2BR (12, 51–53). We have also shown that sustained elevated adenosine causes lung endothelial barrier dysfunction and apoptosis by ENT1/2-dependent intracellular adenosine uptake and subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction (21, 22). In this study, we show that pharmacological inhibition of ENT1/2 significantly increased lung adenosine levels and attenuated P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury. We further show that the protective effect of ENT1/2 inhibition was lost when A2AR and A2BR antagonists were used. These results suggest that adenosine-dependent activation of A2AR and A2BR is the mechanism for ENT1/2 blockade protection against P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury, as depicted in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Proposed mechanism.

The dashed lines represent suggested pathways and the solid lines represent demonstrated pathways.

ENT1 knockout mice and ENT2 knockout mice were both protected from LPS-induced acute lung injury, presumably via elevation of extracellular adenosine (19). Similarly, we show that ENT1 knockout mice were partially protected from P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury. We also noted that NBTI was more protective than ENT1 knockout against P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury. Specifically, ENT1 knockout protected against P. aeruginosa-induced increase in BAL protein content and lung inflammation, but had no effect on P. aeruginosa-induced increase in lung water (wet/dry weight ratio). One possible explanation is the non-specificity of NBTI. Though NBTI is 7000-fold more effective in inhibiting ENT1 than ENT2 (39), we can’t exclude the possibility that the dose (2mg/kg) of NBTI used could inhibit both ENT1 and ENT2. Another possibility may be due to differing expression of ENT1/2 in lung endothelial and epithelial cells. Endothelial cells have been reported to predominantly express ENT1 (24), whereas alveolar epithelial cells predominantly express ENT2 (19, 20). It is likely that ENT1 knockout, via elevation of extracellular adenosine, protects against P. aeruginosa-induced protein leakiness and inflammation, via activation of A2AR and A2BR in lung endothelial cells. The A2BR in alveolar epithelium is responsible for alveolar fluid clearance (17, 43). Inhibition of ENT2 and subsequent activation of A2BR in alveolar epithelium enhances alveolar epithelial cell fluid clearance and dampens ventilation-induced lung injury (20). Intact ENT2 in alveolar epithelium may explain why the ENT1 knockout was not as effective as NBTI in protection of P. aeruginosa-induced increase in lung water. Another possibility could be the dominant role of ENT2 in the lungs. Though ENT1 has a 2.8-fold higher affinity than ENT2 for adenosine (39), ENT2 has been reported as the predominant ENTs for intercellular adenosine uptake in murine lungs and human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC-1) (19). ENT1/ENT2 double knockout and cell type specific ENT1/2 knockout approaches are needed to determine the specific roles of ENT1/ENT2 in P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury. Nonetheless, pharmacological inhibition of ENT1/2 may be a novel effective strategy to prevent and possible treat P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury.

IL-1β and IL18 have been implicated in P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury (32, 33). In this study, we provide evidence supporting P. aeruginosa-induced activation of NLRP3 inflammasome, as indicated by induction of NLRP3 and ASC, as well as activation of caspase-1 and IL-1β. However, the mechanism(s) underlying P. aeruginosa-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation is unknown. Potassium (K+) efflux, Ca2+ influx, mitochondrial dysfunction, mitochondrial oxidative stress, oxidized mitochondrial DNA, and lysosomal leakage have been implicated in NLRP3 inflammasome activation in diverse settings (54). Whether these mechanisms underlie P. aeruginosa-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation is unknown. Adenosine signaling is finely tuned and has pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory roles during tissue injury. Similarly, adenosine can activate or inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome dependent on activation of G protein-coupled adenosine receptors and ENT-mediated intracellular adenosine uptake and metabolism. Sustained millimolar (mM) concentrations of extracellular adenosine have been shown to increase NLRP3 inflammasome expression and activation via ENT2-mediated intracellular adenosine uptake and subsequent metabolism into ATP (55). Adenosine has also been shown to promote nanoparticle-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation partially by Gq family-dependent activation of phospholipase C-β (PLC-β)/ inositol trisphosphate (InsP3)/ cytosolic Ca2+ signaling (55). We have shown that BAL adenosine levels were increased upon P. aeruginosa infection. Whether increased extracellular adenosine contributes to P. aeruginosa-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation via ENT-mediated intracellular adenosine uptake and/or Gq protein-mediated PLC-β/ InsP3/ Ca2+ signaling remains to be determined. It is well known that acute micromolar (μM) concentrations of extracellular adenosine activate cAMP-dependent PKA via A2AR- and A2BR-mediated Gs protein-coupled activation of adenylyl cyclase. PKA has been reported to ubiquitinate and thus degrade NLRP3 via direct phosphorylation of NLRP3 at serine-295 (48). We have shown that both pharmacological inhibition and genetic knockout of ENT1 prevented P. aeruginosa-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation. This effect was associated with extracellular adenosine elevation and A2AR- and A2BR-dependent protection against P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury. Thus, we speculate that ENT1 blockade prevents P. aeruginosa-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation by extracellular adenosine-induced activation of A2AR/A2BR and subsequent PKA-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition. We also speculate that inhibition of intracellular adenosine uptake, due to ENT1 blockade, may contribute to inhibition of intracellular NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Activation of A2AR in alveolar macrophages protects against lung inflammation in humans (56) and mice (57). We demonstrated that inhibition of inflammasome by caspase-1 inhibitor protects against P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury. Taken together, our findings suggest that ENT1/2 blockade protects against P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury via inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome, as depicted in Figure 8.

In summary, we have shown that pharmacological inhibition of ENT1/2 and ENT1 knockout prevented P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury likely via activation of adenosine receptors A2AR and A2BR. We have also demonstrated that both pharmacological and genetic blockade of ENT1 abolished P. aeruginosa-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation, suggesting that inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome may contribute to the protection against P. aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury due to ENT1 inhibition. These results also suggest that targeting ENT1/2 and NLRP3 inflammasome may be novel strategies for prevention and possible treatment of P. aeruginosa-induced pneumonia and subsequent ARDS.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the Providence VA Medical Center for the provision of facilities and institutional support. Funding for this work was derived from NIH-NHLBI grant number HL130230 (Q.L.), NIH-NIGMS grant number P20 GM103652 (S.R. and project 1 to Q.L.), VA Merit Review (S.R.), NIH-NIGMS grant number R35GM118097 (A.A.), NIH-NHLBI grant number HL128661 (G.C.), 1R01AR073284-01A1 (T.W) and NIH-NIEHS grant number T32 ES007272 (to E.C). Some of these results were presented at Experimental Biology conferences in 2016 and 2017 and published in abstract form in FASEB Journal, Volume 30 (supplement), April 1, 2016, abstract # 1262.9; Volume 31 (supplement), April 1, 2017, abstract # 730.4. The authors also thank Dr. Doo-Sup Choi (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) for providing ENT1 null mice and Dr. Troy Stevens (University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL) for providing P. aeruginosa (strain PA103).

Abbreviations:

- ENTs

equilibrative nucleoside transporters

- P. aeruginosa (PA)

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- ALI

acute lung injury

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- NBTI

nitrobenzylthioinosine

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- MDR

multidrug resistance

- VAP

ventilator-associated pneumonia

- AsR

Adenosine receptors

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- PKA

protein kinase A

- ADA

adenosine deaminase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NLR

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (Nod)-like receptor

- PRR

pattern recognition receptors

- PAMPs

pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- DAMPs

damage-associated molecular patterns

- NLRP3

Nod leucine-rich repeat (LRR) and pyrin domain-containing protein 3

- ASC

apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-recruitment domain (CARD)

- Ac-YVAD-cmk

N-Ac-Tyr-Val-Ala-Asp-chloromethyl ketone (a caspase-1 inhibitor)

- IL

interleukin

- PSB1115

4-(2,3,6,7-Tetrahydro-2,6-dioxo-1-propyl-1H-purin-8-yl)-benzenesulfonic acid

- ZM241385

4-(2-[7-Amino-2-(2-furyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[2,3-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol

- BAY60–6583

2-[[6-Amino-3,5-dicyano-4-[4-(cyclopropylmethoxy)phenyl]-2-pyridinyl]thio]-acetamide

- CGS21680

4-[2-[[6-Amino-9-(N-ethyl-β-D-ribofuranuronamidosyl)-9H-purin-2-yl]amino]ethyl]benzenepropanoic acid hydrochloride

- CFU

colony forming units

- TLC

Total lung capacity

- Cst

static lung compliance

- G

tissue damping

- H

tissue elastance

- TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- MIP2

macrophage inflammatory protein-2

- KC

keratinocyte chemoattractant

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

References

- 1.Thompson BT, Chambers RC, and Liu KD (2017) Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. The New England journal of medicine 377, 562–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villar J, Blanco J, and Kacmarek RM (2016) Current incidence and outcome of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care 22, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, van Haren F, Larsson A, McAuley DF, Ranieri M, Rubenfeld G, Thompson BT, Wrigge H, Slutsky AS, Pesenti A, Investigators LS, and Group ET (2016) Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA 315, 788–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC T (2013) Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013 (AR Threats Report). www.cdc.gov

- 5.Ramirez-Estrada S, Borgatta B, and Rello J (2016) Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia management. Infect Drug Resist 9, 7–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibrahim EH, Ward S, Sherman G, and Kollef MH (2000) A comparative analysis of patients with early-onset vs late-onset nosocomial pneumonia in the ICU setting. Chest 117, 1434–1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meduri GU, Reddy RC, Stanley T, and El-Zeky F (1998) Pneumonia in acute respiratory distress syndrome. A prospective evaluation of bilateral bronchoscopic sampling. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 158, 870–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujitani S, Sun HY, Yu VL, and Weingarten JA (2011) Pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa: part I: epidemiology, clinical diagnosis, and source. Chest 139, 909–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasko G, and Cronstein B (2013) Regulation of inflammation by adenosine. Frontiers in immunology 4, 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eltzschig HK (2009) Adenosine: an old drug newly discovered. Anesthesiology 111, 904–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Longhi MS, Robson SC, Bernstein SH, Serra S, and Deaglio S (2013) Biological functions of ecto-enzymes in regulating extracellular adenosine levels in neoplastic and inflammatory disease states. Journal of molecular medicine 91, 165–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu Q, Harrington EO, Newton J, Casserly B, Radin G, Warburton R, Zhou Y, Blackburn MR, and Rounds S (2010) Adenosine protected against pulmonary edema through transporter- and receptor A2-mediated endothelial barrier enhancement. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 298, L755–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Csoka B, Nemeth ZH, Rosenberger P, Eltzschig HK, Spolarics Z, Pacher P, Selmeczy Z, Koscso B, Himer L, Vizi ES, Blackburn MR, Deitch EA, and Hasko G (2010) A2B adenosine receptors protect against sepsis-induced mortality by dampening excessive inflammation. Journal of immunology 185, 542–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackburn MR, Volmer JB, Thrasher JL, Zhong H, Crosby JR, Lee JJ, and Kellems RE (2000) Metabolic consequences of adenosine deaminase deficiency in mice are associated with defects in alveogenesis, pulmonary inflammation, and airway obstruction. J Exp Med 192, 159–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fredholm BB, Arslan G, Halldner L, Kull B, Schulte G, and Wasserman W (2000) Structure and function of adenosine receptors and their genes. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s archives of pharmacology 362, 364–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fredholm BB, AP IJ, Jacobson KA, Linden J, and Muller CE (2011) International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors--an update. Pharmacological reviews 63, 1–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckle T, Faigle M, Grenz A, Laucher S, Thompson LF, and Eltzschig HK (2008) A2B adenosine receptor dampens hypoxia-induced vascular leak. Blood 111, 2024–2035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baldwin SA, Beal PR, Yao SY, King AE, Cass CE, and Young JD (2004) The equilibrative nucleoside transporter family, SLC29. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology 447, 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morote-Garcia JC, Kohler D, Roth JM, Mirakaj V, Eldh T, Eltzschig HK, and Rosenberger P (2013) Repression of the equilibrative nucleoside transporters dampens inflammatory lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 49, 296–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eckle T, Hughes K, Ehrentraut H, Brodsky KS, Rosenberger P, Choi DS, Ravid K, Weng T, Xia Y, Blackburn MR, and Eltzschig HK (2013) Crosstalk between the equilibrative nucleoside transporter ENT2 and alveolar Adora2b adenosine receptors dampens acute lung injury. FASEB J 27, 3078–3089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu Q, Sakhatskyy P, Newton J, Shamirian P, Hsiao V, Curren S, Gabino Miranda GA, Pedroza M, Blackburn MR, and Rounds S (2013) Sustained adenosine exposure causes lung endothelial apoptosis: a possible contributor to cigarette smoke-induced endothelial apoptosis and lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 304, L361–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu Q, Newton J, Hsiao V, Shamirian P, Blackburn MR, and Pedroza M (2012) Sustained adenosine exposure causes lung endothelial barrier dysfunction via nucleoside transporter-mediated signaling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 47, 604–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eltzschig HK, Abdulla P, Hoffman E, Hamilton KE, Daniels D, Schonfeld C, Loffler M, Reyes G, Duszenko M, Karhausen J, Robinson A, Westerman KA, Coe IR, and Colgan SP (2005) HIF-1-dependent repression of equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT) in hypoxia. J Exp Med 202, 1493–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Archer RG, Pitelka V, and Hammond JR (2004) Nucleoside transporter subtype expression and function in rat skeletal muscle microvascular endothelial cells. British journal of pharmacology 143, 202–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strowig T, Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, and Flavell R (2012) Inflammasomes in health and disease. Nature 481, 278–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Zoete MR, Palm NW, Zhu S, and Flavell RA (2014) Inflammasomes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 6, a016287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dolinay T, Kim YS, Howrylak J, Hunninghake GM, An CH, Fredenburgh L, Massaro AF, Rogers A, Gazourian L, Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Landazury R, Eppanapally S, Christie JD, Meyer NJ, Ware LB, Christiani DC, Ryter SW, Baron RM, and Choi AM (2012) Inflammasome-regulated cytokines are critical mediators of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185, 1225–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grailer JJ, Canning BA, Kalbitz M, Haggadone MD, Dhond RM, Andjelkovic AV, Zetoune FS, and Ward PA (2014) Critical role for the NLRP3 inflammasome during acute lung injury. J Immunol 192, 5974–5983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin L, Batra S, and Jeyaseelan S (2017) Deletion of Nlrp3 Augments Survival during Polymicrobial Sepsis by Decreasing Autophagy and Enhancing Phagocytosis. J Immunol 198, 1253–1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fukumoto J, Fukumoto I, Parthasarathy PT, Cox R, Huynh B, Ramanathan GK, Venugopal RB, Allen-Gipson DS, Lockey RF, and Kolliputi N (2013) NLRP3 deletion protects from hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 305, C182–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiang M, Shi X, Li Y, Xu J, Yin L, Xiao G, Scott MJ, Billiar TR, Wilson MA, and Fan J (2011) Hemorrhagic shock activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in lung endothelial cells. J Immunol 187, 4809–4817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schultz MJ, Rijneveld AW, Florquin S, Edwards CK, Dinarello CA, and van der Poll T (2002) Role of interleukin-1 in the pulmonary immune response during Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 282, L285–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schultz MJ, Knapp S, Florquin S, Pater J, Takeda K, Akira S, and van der Poll T (2003) Interleukin-18 impairs the pulmonary host response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun 71, 1630–1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens TC, Ochoa CD, Morrow KA, Robson MJ, Prasain N, Zhou C, Alvarez DF, Frank DW, Balczon R, and Stevens T (2014) The Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme Y impairs endothelial cell proliferation and vascular repair following lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 306, L915–924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu Q, Sakhatskyy P, Grinnell K, Newton J, Ortiz M, Wang Y, Sanchez-Esteban J, Harrington EO, and Rounds S (2011) Cigarette smoke causes lung vascular barrier dysfunction via oxidative stress-mediated inhibition of RhoA and focal adhesion kinase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301, L847–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borgas D, Chambers E, Newton J, Ko J, Rivera S, Rounds S, and Lu Q (2015) Cigarette Smoke Disrupted Lung Endothelial Barrier Integrity and Increased Susceptibility to Acute Lung Injury via Histone Deacetylase 6. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blackburn MR, Aldrich M, Volmer JB, Chen W, Zhong H, Kelly S, Hershfield MS, Datta SK, and Kellems RE (2000) The use of enzyme therapy to regulate the metabolic and phenotypic consequences of adenosine deaminase deficiency in mice. Differential impact on pulmonary and immunologic abnormalities. The Journal of biological chemistry 275, 32114–32121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suresh Kumar V, Sadikot RT, Purcell JE, Malik AB, and Liu Y (2014) Pseudomonas aeruginosa induced lung injury model. J Vis Exp, e52044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ward JL, Sherali A, Mo ZP, and Tse CM (2000) Kinetic and pharmacological properties of cloned human equilibrative nucleoside transporters, ENT1 and ENT2, stably expressed in nucleoside transporter-deficient PK15 cells. Ent2 exhibits a low affinity for guanosine and cytidine but a high affinity for inosine. J Biol Chem 275, 8375–8381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baldwin SA, Mackey JR, Cass CE, and Young JD (1999) Nucleoside transporters: molecular biology and implications for therapeutic development. Mol Med Today 5, 216–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Visser F, Vickers MF, Ng AM, Baldwin SA, Young JD, and Cass CE (2002) Mutation of residue 33 of human equilibrative nucleoside transporters 1 and 2 alters sensitivity to inhibition of transport by dilazep and dipyridamole. J Biol Chem 277, 395–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antonioli L, Csoka B, Fornai M, Colucci R, Kokai E, Blandizzi C, and Hasko G (2014) Adenosine and inflammation: what’s new on the horizon? Drug Discov Today 19, 1051–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eckle T, Grenz A, Laucher S, and Eltzschig HK (2008) A2B adenosine receptor signaling attenuates acute lung injury by enhancing alveolar fluid clearance in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation 118, 3301–3315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lovewell RR, Patankar YR, and Berwin B (2014) Mechanisms of phagocytosis and host clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 306, L591–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furuta GT, Atkins FD, Lee NA, and Lee JJ (2014) Changing roles of eosinophils in health and disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 113, 3–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Linch SN, Kelly AM, Danielson ET, Pero R, Lee JJ, and Gold JA (2009) Mouse eosinophils possess potent antibacterial properties in vivo. Infect Immun 77, 4976–4982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koller DY, Gotz M, Eichler I, and Urbanek R (1994) Eosinophilic activation in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 49, 496–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eltzschig HK, Ibla JC, Furuta GT, Leonard MO, Jacobson KA, Enjyoji K, Robson SC, and Colgan SP (2003) Coordinated adenine nucleotide phosphohydrolysis and nucleoside signaling in posthypoxic endothelium: role of ectonucleotidases and adenosine A2B receptors. J Exp Med 198, 783–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, and Linden J (2001) International union of pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacological Review 53, 527–552 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson CN, and Batra VK (2002) Lipopolysaccharide binds to and activates A(1) adenosine receptors on human pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Endotoxin Res 8, 263–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eckle T, Koeppen M, and Eltzschig HK (2009) Role of extracellular adenosine in acute lung injury. Physiology (Bethesda) 24, 298–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barletta KE, Ley K, and Mehrad B (2012) Regulation of neutrophil function by adenosine. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32, 856–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu H, Yu X, Yu S, and Kou J (2015) Molecular mechanisms in lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary endothelial barrier dysfunction. Int Immunopharmacol 29, 937–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He Y, Hara H, and Nunez G (2016) Mechanism and Regulation of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Trends Biochem Sci 41, 1012–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baron L, Gombault A, Fanny M, Villeret B, Savigny F, Guillou N, Panek C, Le Bert M, Lagente V, Rassendren F, Riteau N, and Couillin I (2015) The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by nanoparticles through ATP, ADP and adenosine. Cell Death Dis 6, e1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alfaro TM, Rodrigues DI, Tome AR, Cunha RA, and Robalo Cordeiro C (2017) Adenosine A2A receptors are up-regulated and control the activation of human alveolar macrophages. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 45, 90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aggarwal NR, D’Alessio FR, Eto Y, Chau E, Avalos C, Waickman AT, Garibaldi BT, Mock JR, Files DC, Sidhaye V, Polotsky VY, Powell J, Horton M, and King LS (2013) Macrophage A2A adenosinergic receptor modulates oxygen-induced augmentation of murine lung injury. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 48, 635–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]