Abstract

Transcription is the fundamental process that enables the expression of genetic information. DNA-directed RNA polymerase (RNAP) uses one strand of the DNA duplex as template to produce complementary RNA molecules that serve in translation (rRNA, tRNA), protein synthesis (mRNA), and regulation (sRNA). Although the RNAP core is catalytically competent for RNA synthesis, the selectivity of transcription initiation requires a sigma (σ) factor for promoter recognition and opening. Expression of alternative σ factors provides a powerful mechanism to control the expression of discrete sets of genes (a σ regulon) in response to specific nutritional, developmental, or stress-related signals. Here, I review the key insights that led to the original discovery of σ factor 50 years ago and the subsequent discovery of alternative σ factors as a ubiquitous mechanism of bacterial gene regulation. These studies form a prelude to the more recent, genomics-enabled insights into the vast diversity of σ factors in Bacteria.

ABBREVIATED SUMMARY

The sigma subunit of RNAP was first purified 50 years ago by Burgess et al. (1969) and shown to function as a dissociable subunit to allow recognition of specific transcription start sites (promoters). Subsequent studies have revealed that sigma factor replacement with alternative sigma factors (including ECF sigma factors) is potent transcriptional regulatory mechanism in Bacteria.

“Begin at the beginning,” the King said, very gravely, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

INTRODUCTION

The current revolution in biology is premised on our understanding of the role of DNA as the genetic material. The “central dogma” asserts that DNA is the repository of genetic information, and this information is used for expression of RNA and protein through the sequential processes of transcription and translation, respectively. DNA itself can be an enormous polymer, with bacterial chromosomes usually containing well in excess of 106 bp, and chromosomes in eukaryotes typically much larger. The selective expression of this material implies there are well coordinated mechanisms that determine where and when specific genes and operons are transcribed into RNA. Similarly, RNA molecules must include signals that tell the ribosome where to begin and where to end during protein synthesis.

Here, I will review some of the key events that led to the discovery of bacterial σ factors and their role in promoter recognition, and the ability of σ substitution to serve as a powerful regulatory mechanism. My goal will be to put the discovery of ECF σ factors in a broad historical context. These early studies, particularly those leading to the discovery of σ (50 years ago), and leading to the identification of alternative σ factors in bacteria (40 years ago), provide insights into the challenges of dissecting complex enzyme mechanisms at a time when the tools that power contemporary biology (e.g. DNA cloning and restriction enzymes, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and DNA sequencing) were yet to be invented.

The characterization of template-dependent nucleic acid polymerases

Perhaps the most logical place to begin this story is the landmark paper describing a proposed structure and likely mechanism of replication for DNA as published by Watson and Crick in 1953 (Watson & Crick, 1953). One key insight from the structure was famously summarized in the following sentence: “It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material.” However, what was not apparent was how this would occur. The answer would emerge from the laboratory of Arthur Kornberg who purified the first DNA-directed DNA polymerase and demonstrated that this enzyme could copy DNA in the test tube. One might imagine that these studies simply looked for an enzyme that could “copy” DNA in the presence of all four substrates (deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates, dNTPs). The actual studies were far more intricate, and involved a complex fractionation to determine the components of an Escherichia coli cell extract needed for the incorporation of one added substrate (32P-labeled dTMP) into a polymeric form precipitable by acid. Fractionation of the extract revealed the requirement for DNA, the four nucleotides, and associated nucleotide kinases (Kornberg, 1989, Lehman, 2003). As Kornberg recalls, the original rationale for including DNA in the in vitro reactions was based on the assumption it would serve as a primer for polymer synthesis, rather than as template, and that it would also help shield any newly synthesized material from DNases (Kornberg, 1989).

These early (1955) studies of DNA synthesis were the beginning of efforts that established several facts familiar to molecular biologists today: dNTPs are the substrates, synthesis is 5’ to 3’ and requires both a primer and a single-stranded DNA template, and synthesis is processive. That these early insights were gleaned from studies of an enzyme that turned out not to be the replicative DNA polymerase was of minor consequence, since these properties are universal. The enzyme activity that Kornberg initially characterized was, unexpectedly, found to not be the major replicative polymerase (De Lucia & Cairns, 1969), and functions instead in DNA repair and primer removal (DNA polymerase I). Replication involves a larger and more complex assemblage of proteins (the DNA polymerase III holoenzyme) (McHenry, 1991). Kornberg and legions of subsequent researchers would fill in the details of how DNA polymerase knows where to begin (at sites called origins), how primases, helicases, topoisomerases, and numerous other accessory factors enable efficient replication, and how replication terminates and chromosomes segregate.

The early history of RNA polymerase is in many ways intertwined with and motivated by these early biochemical studies of DNA polymerase. Indeed, the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1959 was awarded jointly to Severo Ochoa and Arthur Kornberg “for their discovery of the mechanisms in the biological synthesis of ribonucleic acid and deoxyribonucleic acid.” Although Marianne Grunberg-Manago and Severo Ochoa had discovered an RNA polymerase activity, this enzyme (polynucleotide phosphorylase; PNPase) is involved in RNA degradation in cells, and not synthesis (Grunberg-Manago, 1989). Even at the time of the award, it was apparent that PNPase was likely not a template-directed enzyme. Nevertheless, PNPase provided a valuable tool for the in vitro synthesis of RNA copolymers of various composition that then proved essential to the rapid deciphering of the genetic code (by determining which amino acids where incorporated by ribosomes bound to RNAs of known base composition, but not sequence). Ochoa himself has stated that PNPase “may be considered to have been the Rosetta Stone of the genetic code” (Ochoa, 1980).

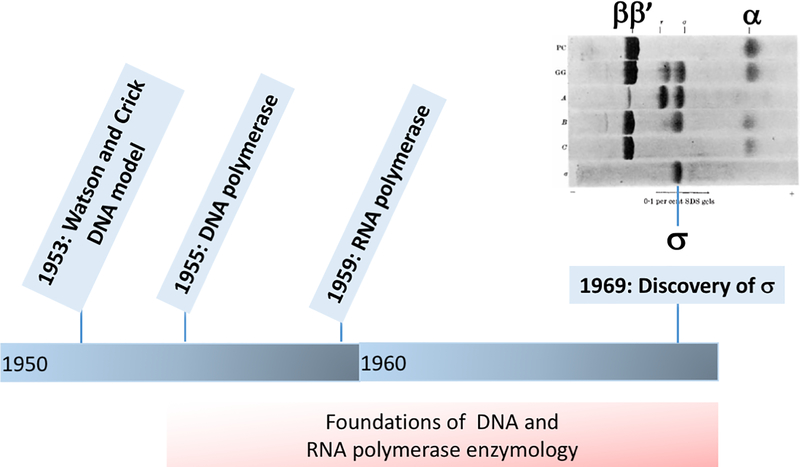

The first biochemical evidence for the template-directed RNA polymerase (RNAP) necessary for transcription emerged from purification of activities that synthesized RNA in a reaction requiring NTPs, and specifically stimulated by the addition of a DNA template (Fig. 1). By 1960, such activities had been detected independently in four different laboratories working with rat liver nuclei (Samuel Weiss), Escherichia coli (Jerry Hurwitz and Audrey Stevens), and pea extracts (James Bonner) (reviewed in Hurwitz, 2005, Kresge et al., 2006). The typical assay used in these studies was to monitor the incorporation of 32P-radiolabelled NTPs into an acid-insoluble product that could be trapped on a filter and quantitated. A key challenge in these early studies was to demonstrate that the RNA was a product of template-directed transcription. Even demonstrating the DNA-dependence of the reaction was a challenge since this required the development of purification methods for RNAP that could efficiently separate it from DNA and ribonucleases also present in the extracts. Next, it was necessary to document that the nucleotide composition of the RNA product was broadly reflective of that of the substrate. As one approach, the synthetic copolymer poly-d(AT) could be used as template. Although initial efforts were met with mixed success due to nuclease contamination (Hurwitz, 2005), Michael Chamberlin and Paul Berg developed a robust purification method and demonstrated that the product was RNA with the expected composition (poly-r(AU)) (Chamberlin & Berg, 1962).

Fig. 1. DNA and RNA synthesis up to the discovery of σ.

Early studies of DNA and RNA synthesis were enabled by biochemical approaches, including the purification and characterization of the enzymes and their substrate requirements. Unlike DNA polymerase, RNA polymerase does not require a pre-existing primer for synthesis, and can recognize start sites (promoters). This latter activity requires the σ subunit, discovered in 1969 (inset is adapted from Burgess et al., 1969).

The demonstration that RNAP could catalytically copy a DNA template into RNA was ultimately supported by two major types of study. First, it could be demonstrated that the template composition of the RNA product was reflective of the DNA template using a nearest neighbor analysis of dinucleotide composition (modern sequencing methods were not yet invented). Moreover, Chamberlin and Berg showed that the amount of RNA product could exceed the amount of DNA template, indicative of a catalytic reaction in which each template could be used more than once (Chamberlin & Berg, 1962). Second, the RNA product could be shown to anneal specifically to the DNA template used for its synthesis, suggestive of specificity (Geiduschek et al., 1961). These were challenging experiments, and involved the in vitro synthesis of 32P-radiolabelled RNA, the use of diverse DNA templates, and the separation of RNA, DNA, and RNA-DNA hybrids by cesium chloride (CsCl) ultracentrifugation. Having established that RNAP could be purified in an active form, and that RNA synthesis seemed to be template-directed, the stage was now set for studies to define the start and stop signals that must determine transcriptional selectivity in cells.

The discovery of sigma (σ) and the molecular basis for promoter recognition

With the availability of purified preparations of bacterial RNAP, and ample evidence that cells contained a short-lived RNA intermediate that could be used to program ribosomes for protein synthesis (mRNA), the challenge emerged of reconstituting the specificity of transcription initiation in vitro. The key observation, made independently by Richard Burgess and Andrew Travers (Harvard) and by John Dunn and Ekkehard Bautz (Rutgers), was that E. coli RNAP could be purified in two distinct forms that we would now recognize as the core and holoenzymes (Burgess et al., 1969). The core enzyme, obtained in a protocol culminating with phosphocellulose chromatography had subunit composition ββ’α2 (Burgess, 1969), but was poorly active on purified phage T4 DNA while retaining activity on calf thymus DNA. Conversely, if the final purification was instead a glycerol gradient, the resulting enzyme retained high activity with the T4 template (Burgess et al., 1969). Moreover, further fractionation of this enzyme led to the separation of core and holoenzyme components, as visualized by the newly introduced technique of SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1). When the σ factor was itself purified and added back to the core enzyme, high activity with the T4 template was restored, and σ could act catalytically to initiate RNA chains (Travers & Burgess,1969). This factor, then, seemed to answer the question: how does RNAP know where to begin? Presciently, even at this early stage Burgess noted that, “the interesting possibility arises that several similar factors could exist, each with a specificity for a different type of initiation site” (Burgess et al., 1969).

With these early insights into the specificity of initiation, attention was also drawn to the converse question: how does RNAP know where to stop synthesis? Jeff Roberts, working in the same Harvard Biological Laboratories as Dick Burgess, described the Rho transcription termination factor based on its activity on in vitro transcription of λ DNA (Roberts, 1969). These two Nature papers, reporting the discovery of σ and Rho, appeared (appropriately) at the beginning and end of 1969, respectively. Unlike σ, the Rho subunit is not required for all termination events and core RNAP itself recognizes intrinsic terminators at the end of many transcription units. However, Rho plays an important role in preventing transcription of horizontally transcribed DNA and long, untranslated stretches of RNA and is an essential protein in many bacteria (Mitra et al., 2017).

Biochemically, one of the key insights that emerged during this first decade of studying RNAP is that analysis of the biologically relevant transcription reaction required a well-defined template. In this era, prior to advent of restriction enzymes and molecular cloning technologies (let alone PCR), phage DNA provided such a template. Lytic phage can be purified in large quantities from lysates and the DNA extracted for biochemical use. Moreover, since many phage rely on host RNAP for early transcription, the corresponding early promoters are often highly active. In contrast, calf thymus and other more complex DNA preparations consist of randomly sheared fragments and are riddled with nicks, gaps, and single-stranded regions that bind RNAP and in some cases bypass the need for the σ subunit for initiation (Aiyar et al., 1994, Fredrick & Helmann, 1997). The use of purified phage DNA as template was also critical to the first successful efforts to identify alternative σ factors (see below).

In the decade following the discovery of σ factor the essential features of the bacterial transcription cycle would emerge, and the basic architecture of bacterial promoter sites was established (Chamberlin, 1976). Numerous studies, including many from the lab of Michael Chamberlin (UC Berkeley), established the distinction between closed and open complexes, and the temperature dependence of open complex formation led to the idea that this step was associated with localized melting of promoter region DNA to expose the template strand (Chamberlin, 1974). For these studies, the three strong promoters at one end of the phage T7 genome served as a model. The first insights into the nature of promoter recognition emerged when David Pribnow biochemically purified a DNA fragment bound to RNAP and then used this fragment to purify RNA sequences that annealed to this region and could be sequenced (sequencing RNA was easier than DNA at the time) (Pribnow, 1975). The conservation of the TATAAT sequence providing a first glimpse of what would later be known as the core consensus elements located near −35 and −10 relative to the transcription start site (Losick & Pero, 1981).

Alternative σ factors in bacteriophage gene regulation

Despite very active interest in bacterial RNA polymerase, evidence of alternative σ factors was not immediately forthcoming. Nevertheless, efforts towards defining mechanisms of altering transcriptional selectivity were successful. Of particular note, soon after the discovery of σ, Chamberlin sought to purify the transcription factor needed for late transcription in phage T7, expecting that this protein might be an alternative σ factor. The product of gene 1 was unexpectedly found to be a stand-alone, single-subunit RNAP rather than an alternative σ factor for the host RNAP (Chamberlin et al., 1970) (Fig. 2). The revelatory insight came when it was observed that the active fraction was insensitive to rifampicin (which inhibits all core RNAP activity); a notable example of how a “failed” control experiment foretold a major discovery. T7 RNAP proved to be a boon to biotechnology and was subsequently harnessed for numerous applications, including protein and RNA overproduction for biochemical analyses, RNA interference, and systems biology applications (Studier et al., 1990, Borkotoky & Murali, 2018, Wang et al., 2018). More recently, T7 RNA polymerase has been key to the synthesis of large amounts of RNA for clinical use (Jain et al., 2018).

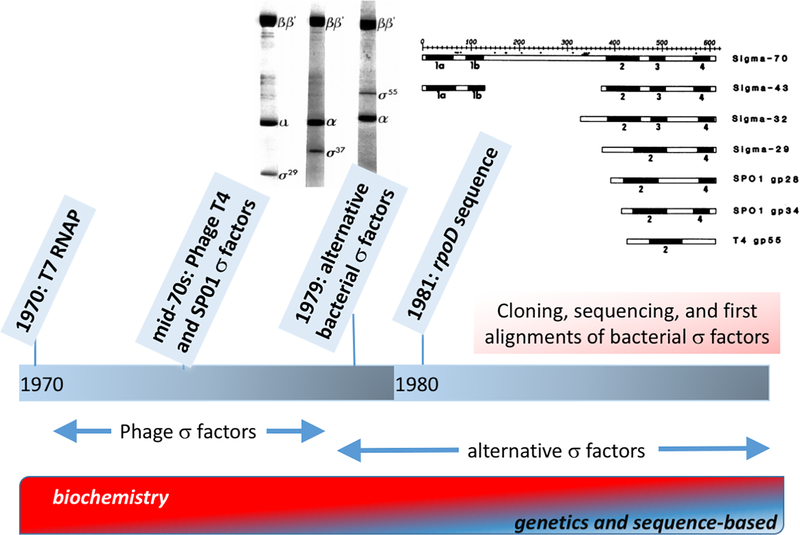

Fig. 2. The discovery of alternative σ factors.

Efforts to determine if RNA polymerase can be re-programmed by alternative σ subunits focused initially on bacteriophage systems. These efforts led to the discovery of the single-subunit T7 RNAP, and specificity factors that function (more or less) as σ factors from phage T4 and B. subtilis phage SP01. By 1980, several alternative σ factors were identified in B. subtilis (inset adapted from Losick & Pero, 2018). A convergence of biochemical and genetic approaches soon revealed a rich diversity of bacterial σ factors and led to the first efforts to define subgroups within the growing σ70 family (inset adapted from Gribskov & Burgess, 1986).

Evidence for the role of alternative σ factors regulating gene expression first emerged from studies of phage systems (Fig. 2). The phage T4 gp33 and gp55 proteins were found to be necessary for middle- and late-transcription, respectively, and both proteins can be purified bound to RNAP from infected cells. However, it was not initially clear if these proteins were, in fact, bona fide σ factors and the requirements for template activation proved to be complex (Geiduschek & Kassavetis, 2010). Biochemical evidence that phage encode regulators that can function in place of the host σ factor to redirect transcription was clearly documented by the studies of Tom Fox and Jan Pero working with Bacillus subtilis phage SP01 (Pero et al., 1975, Fox et al., 1976, Fox & Pero, 1974). In these landmark studies, Pero and her colleagues established that SP01 gp28 is a σ factor for middle genes, and gp33/34 appear to form a two-component σ (or σ-like) for late genes (Tijan & Pero, 1976). Thus, by the mid-1970s the concept of alternative σ factors had gained strong support (Fig. 2), but it remained unclear whether this same regulatory mechanism might be used by bacteria to regulate gene expression.

Key to each of these early studies was the availability of pure phage DNA templates that could be used for analysis of transcription selectivity. The challenge of identifying and characterizing promoters from the much more complex bacterial chromosome, as a needed assay for the purification and study of endogenous alternative σ factors, is emphasized by the title of a recent retrospective from Richard Losick and Jan Pero, “For Want of a Template” (Losick & Pero, 2018).

Biochemical identification of alternative σ factors involved in bacterial gene regulation

The first indications that bacteria may also employ alternative σ factors to regulate gene expression emerged from biochemical studies of RNAP purified from B. subtilis, an organism with a complex developmental program culminating in endospore formation. Within months of the original report of σ factor, Losick and Sonenshein had determined that RNAP from vegetative and sporulating B. subtilis cells differed dramatically in template selectivity; whereas both preparations were highly active with poly-d(AT), only the former was active with Bacillus phage ϕe DNA as template (Losick & Sonenshein, 1969). These observations led to the first suggestion that sporulation might be driven, at least in part, by a σ substitution mechanism. In a brief note added in proof, the authors also noted that E. coli σ factor (as purified by Burgess) could also restore transcription of ϕe DNA when added to the B. subtilis core enzyme. This remarkable result highlights the extent of RNAP conservation in these two bacteria, now thought to have diverged in evolution more than 3 billion years ago. In a series of studies over the next decade, the Losick laboratory documented the existence of sporulation-associated proteins that co-fractionated with RNAP, and a correlated loss of the primary σ factor during sporulation. However, demonstration of σ activity for these new, RNAP-associated factors could not be easily documented “for want of a template” (Losick & Pero, 2018).

The key breakthrough for defining the activity of alternative sporulation σ factors was the ability to identify and clone DNA fragments containing the cognate, developmentally regulated promoters. This led to initial identification of the σ37(σB) and σ29(σE), although the former turned out to be involved in general stress response regulation rather than dedicated to sporulation (Haldenwang et al., 1981, Haldenwang & Losick, 1979, Haldenwang & Losick, 1980) (Fig. 2). At this stage, the many newly identified candidate σ factors were identified by their molecular weight on SDS-PAGE gels (Fig. 2). Confirmation of σ factor activity was possible in many cases by simply excising the candidate σ factor band from after SDS-PAGE and renaturation of the polypeptide, which could then be added back to core RNAP to restore selectivity (Hager & Burgess, 1980). By 1981, the general theme that σ substitution was a driving force for sporulation had emerged, and it had become clear that σ switching directly altered the preferred sequences within the promoter at both the −35 and −10 elements (Lee & Pero, 1981, Moran et al., 1981). Thus emerged the first hints of the complex scheme of criss-cross regulation between the developing mother cell and forespore (Losick & Pero, 1981).

In parallel with the efforts in the Losick lab to understand the biochemical basis for transcriptional switching during sporulation, work in the Chamberlin lab was also directed at characterization of a newly defined σ factor, σ28(σD). This activity was serendipitously discovered during efforts to ascertain the extent of conservation of RNAP selectivity amongst bacteria. Preparations of RNAP from seven divergent bacterial species were all found to recognize the same set of strong promoters on phage T7 DNA (Wiggs et al., 1979). However, the B. subtilis enzyme also gave rise to a transcript not seen with the other preparations (Jaehning et al., 1979), and subsequent fractionation revealed that this activity required a 28 kDa protein, σ28(σD) (Wiggs et al., 1981).

Efforts to define the promoter selectivity of σ28, and the biological role of this protein, were to occupy several members of the Chamberlin lab over the subsequent years. This includes five years I invested in finding and sequencing the corresponding gene, sigD, during my PhD studies. The strategy reflected the then ascendant approach of biochemistry; I purified RNA polymerase from kg quantities of bacterial cell paste to obtain mg quantities of RNAP that then allowed the isolation and renaturation of μg quantities of σ28 polypeptide (Helmann et al., 1988b). With partial amino acid sequences in hand, it was possible to design degenerate DNA probes for recovery of the corresponding gene (Helmann et al., 1988a). This same approach was later used by Mark Buttner to clone the gene for Streptomyces coelicolor σE, which was a key enabling event in the discovery of the ECF σ factors (Lonetto et al., 1994).

In parallel with my ongoing efforts to clone the sigD gene, the corresponding consensus sequence for recognition by the σ28 holoenzyme was becoming clear (Gilman et al., 1984, Gilman et al., 1981). The culmination of these studies was the realization that the characteristic promoter sequences recognized by σ28 (which, I fear, are forever embossed on my mind) are highly conserved amongst bacteria, and that σ28 factors are often involved in expression of genes related to chemotaxis and motility (Helmann & Chamberlin, 1987). Indeed, we subsequently found that expression of the B. subtilis sigD gene in a non-flagellated and non-motile E. coli fliD mutant, lacking the orthologous σ28 protein, led to the growth of flagellar filaments and restoration of motility (Chen & Helmann, 1992). This result highlights the remarkable conservation of not only the core RNAP machinery, but also an alternative σ factor, which therefore likely evolved very early (likely >3 billion years ago) in the evolutionary diversification of Bacteria. To my knowledge, this type of genetic complementation of σ function between such divergent bacteria has not been seen for any other class of alternative σ factor. It makes sense that both σ structure and promoter selectivity might be highly conserved, since σ28 controls a substantial regulon, and this presumably limits genetic drift at the level of promoter sequences, and therefore also σ structure.

Impact of DNA sequencing and genetics on identification of alternative σ factors

By the early-80s, the newly developed dideoxy-based (Sanger) technique for DNA sequencing (introduced in 1977; Sanger et al., 1977) was widely adopted, and the first complete sequences for genes encoding σ factors were starting to emerge. The first to be identified was E. coli rpoD, in studies from Carol Gross and Richard Burgess (Burton et al., 1981, Gross et al., 1979) (Fig. 2). By 1985, the primary σ factors from E. coli and B. subtilis were recognized as homologous proteins, despite their size differences (Gitt et al., 1985). The primary σ of E. coli migrates in SDS-PAGE at 90 kDa, but the protein mass is 70 kDa (and therefore named σ70), whereas the B. subtilis primary σ (previously known as σ55) was found to have an actual mass of 43 kDa (and renamed σ43). This confusing situation with σ nomenclature was even worse with the B. subtilis alternative σ factors since many had very similar apparent molecular weights (σ27, σ28, σ29). A solution was forthcoming, however, with the proposal from Losick et al. that σ factors be designed with letters rather than numbers, which had the added advantage that the corresponding gene names would adhere to the established conventions of bacterial gene nomenclature (Losick et al., 1986). Following this suggestion, the primary sigma factors were renamed as σA, with alternative σ factor σ37 becoming σB (encoded by sigB), σ28 becoming σD (encoded by sigD), and so forth. This system proved quite adaptable, and only faced a serious challenge with the expansion of the σ family to include ECF σ factors, which together with exponential increases in the sequence databases, led to the realization that some bacteria have more (and sometimes far more) than 26 σ factors. There were some exceptions to this naming system, for largely historical reasons. In E. coli, for example, the σ factors are encoded by rpo genes (e.g. rpoD for σA and rpoH, rpoS, etc. for alternative σ factors).

As Sanger sequencing technology was widely adopted by bacteriologists, the sequences emerged of many genes known to encode factors that activated transcription, but by unknown mechanisms. This led to the emergence of a whole new set of σ factors, which in many cases were first glimpsed as DNA sequences rather than as bands on an SDS-gel of a purified RNAP fraction. One early example was the realization that htpR, an E. coli gene known to encode a high-temperature protein regulator, encoded an alternative σ factor (σ32, and later σH or RpoH) (Landick et al., 1984, Grossman et al., 1984). Another E. coli regulator encoded by katF controls catalase expression and encodes the stationary phase regulator, σS (renamed rpoS) (Mulvey & Loewen, 1989), and the whiG developmental regulator from Streptomyces coelicolor was found to encode a close homolog of B. subtilis σ28 (Chater et al., 1989). Conversely, a central nitrogen regulator, ntrA, was found to encode a protein that looked nothing like other σ factors, despite having demonstrable σ activity (Hirschman et al., 1985). This σ serves as the prototype for the large family of activator-dependent σ factors of the so-called σ54 family (Merrick, 1993, Danson et al., 2019).

One significant outcome of the rapid growth of the σ family tree was the ability to define the key protein sequence features that would come to define σ factors. Comparisons of the DNA sequences of the first available genes encoding σ factors led to a seminal paper from Gribskov and Burgess (1986), which noted that primary σ factors have four conserved regions, numbered 1 through 4 (Gribskov & Burgess, 1986) (Fig. 2). However, there was considerable variability, and some sequences appeared to lack a well conserved region 1 and/or 3, and in the case of the more divergent proteins that function as alternative σ factors for phage, sometimes only a single region was recognizable. This early recognition of the high potential variability within the larger σ family foreshadowed the 1994 description of the extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sub-family as comprising those σ factors with only regions 2 and 4 (Lonetto et al., 1994).

With a combination of clever bacterial genetic approaches, and DNA sequencing to identify the resulting sequence changes, the late 1980s also witnessed the emergence of a detailed model for promoter recognition by bacterial σ factors. In acknowledgement of the unusual σ54 family proteins (which have a different overall promoter structure), these studies are generally described as applying to σ70 family proteins (the large family of proteins with similarity to σ70, including all alternative σ factors except the σ54 family). The resulting model posits that σ70 conserved region 4 functions as a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding module that recognizes the −35 element (as duplex DNA), whereas σ70 region 2 has elements important for both binding to core RNAP and recognition of the −10 element (Gardella et al., 1989, Siegele et al., 1989, Zuber et al., 1989). These interactions correlate with conserved regions in bacterial σ70 family proteins, and their consideration led to a more refined nomenclature for the conserved σ regions dividing, for example, region 2 into regions 2.1 through 2.4 (Helmann & Chamberlin, 1988). While these divisions proved a useful shorthand for discussing the function of discrete modules (or sequence units), the true relationship between these conserved elements and protein structural domains was not immediately clear. In this early review, we also introduced the notion that σ factor, and in particular conserved aromatic amino acids in conserved region 2.3, participates directly in DNA strand separation (promoter melting) during the closed- to open-promoter transition (Helmann & Chamberlin, 1988). Specifically, we postulated that conserved aromatic amino acids could provide a protein scaffold for stacking with the bases of the displaced non-template in the transcription bubble, a prediction largely supported and refined by a number of subsequent genetic and structural studies (Feklistov et al., 2014).

The comparative sequence analysis of bacterial σ factors was further extended using a substantially larger dataset of sequences in 1992 (Lonetto et al., 1992). This study revealed, for example, that σ region 2.3, involved in DNA-melting, was much less well conserved in alternative σ factors. Much later, it was appreciated that for some of these alternative σ factors a lack of strong conservation in region 2.3 is correlated with weaker promoter melting activity, and consequently a stronger reliance on the initial promoter recognition binding event. This also correlates with an overall higher conservation of cognate promoter consensus sequences (Koo et al., 2009).

Expansion of the σ family to include the ECF σ factors

The studies above, encompassing the first ~25 years of σ history, form the backdrop for the discovery of the extracytoplasmic (ECF) σ factors. Many of the genes that encode ECF σ factors were first identified for their regulatory role, and even when their sequences were determined, many were not immediately recognized as σ factors despite, in some cases, apparent similarity to the larger σ70 family. In some ways, this is surprising since these genes encode proteins more closely related to conventional σ factors than the phage σ factors included in the original (1986) Gribskov and Burgess alignments (Gribskov & Burgess, 1986). The key convergence that led to the integration of these sequences as part of the σ family tree, and as founding members of the ECF sub-family, came from the realization that Streptomyces coelicolor σE (as characterized by traditional protein purification and reconstitution methods; Buttner et al., 1988) was encoded by a gene clearly related to several other “transcription factors” (Myxococcus xanthus CarQ, Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgU, Pseudomonas syringae HrpL, E. coli σE and FecI, Alcaligenes eutrophus CnrH, and Bacillus subtilis SigX) not yet shown to function as σ factors (Lonetto et al., 1994) (Fig. 3). It was quickly appreciated that some bacteria contain multiple ECF σ factors, a phenomenon first explored systematically in the B. subtilis model system (Helmann, 2002).

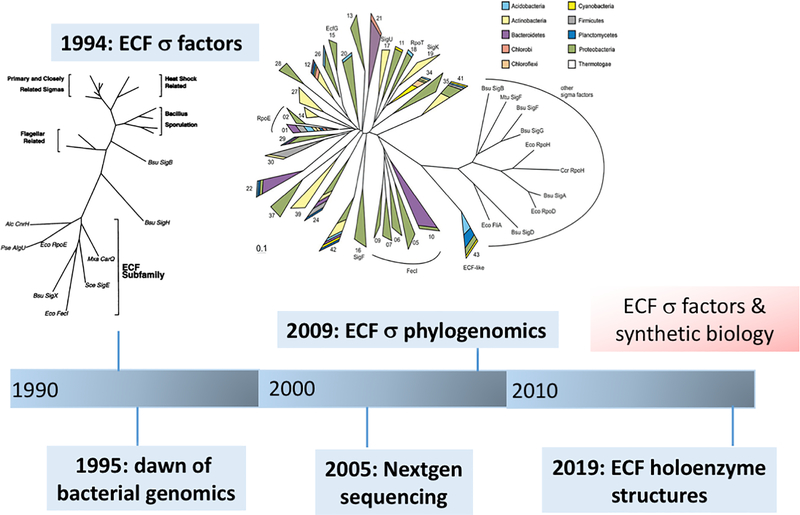

Fig 3. ECF σ factors and the age of genomics.

With increasing availability of DNA sequence information, the genetic diversity of σ factors became appreciated. The ECF subgroup was identified in 1994 (inset from Lonetto et al., 1994), and 1995 marked the beginning of the era of bacterial genomics. By 2009, phylogenomics-based approaches revealed that ECF σ factors were a highly diverse and often numerically dominant subset of alternative σ factors that play major roles, in many cases yet to be determined, in bacterial gene regulation (inset from Staron et al., 2009).

In studies in my group over the last two decades we have generated mutant strains lacking each of the seven ECF σ factors encoded by B. subtilis. These ECF σ factors are both individually and collectively dispensable (Luo et al., 2010), but the resulting mutant strains have a greatly increased sensitivity to specific stresses (Mascher et al., 2007). In our earliest studies, we took advantage of the fact that many ECF σ factor genes are autoregulatory to identify and characterize cognate promoters (Huang et al., 1999, Huang & Helmann, 1998). Detailed promoter mutagenesis studies yielded insights into the conserved bases that defined the −35 and −10 elements (Huang et al., 1998), which then allowed sequence-based identification of candidate promoters from the genome sequence (Huang et al., 1999, Huang & Helmann, 1998). Remarkably, some ECF σ promoter consensus sequences differed by as little as a single base in the −10 element, and substitutions at this position could transfer a promoter from one regulon to another (Qiu & Helmann, 2001). The high conservation of promoters recognized by ECF σ factors also facilitated computational approaches to predict regulons in several other systems, including the σE regulon in E. coli and its close relatives (Rhodius et al., 2006) and in Rhodobacter sphaeroides (Dufour et al., 2008).

By carefully delineating the regulatory scope of each B. subtilis ECF σ factor (the regulon), often using a combination of complementary approaches (Cao et al., 2002a, Eiamphungporn & Helmann, 2008), we were able to derive insights into the likely role of each σ and predict relevant inducing conditions (Cao et al., 2002b, Guariglia-Oropeza & Helmann, 2011). Our results, together with those from others, indicates that σX controls cell surface modifications that impart resistance to antimicrobial peptides (Cao & Helmann, 2004) and has been coopted by phage SPβ to regulate sublancin production (Luo & Helmann, 2009), σW protects cells against a variety of antibacterial agents including bacteriocins and cell membrane disruptive agents (Cao et al., 2001, Butcher & Helmann, 2006, Luo et al., 2010, Kingston et al., 2011), σM is critical in regulating cell envelope synthesis and in resistance to agents that interfere with peptidoglycan synthesis (Luo & Helmann, 2012, Meeske et al., 2015), and σV is specifically implicated in defense against lysozyme (Guariglia-Oropeza & Helmann, 2011, Ho et al., 2011). Although we now have a reasonably complete understanding of the regulatory scope for these four ECF σ factors (Helmann, 2016), the roles of the other three (which appear to have much more proscribed regulons; Asai et al., 2003) are less well understood.

As the large family of σ factors has rapidly expanded, so too has the sophistication of our understanding of all aspects of RNA polymerase structure and function. Structural studies, many using X-ray crystallography, have gradually emerged for σ factors and their domains, RNA polymerase holoenzyme, and ultimately holoenzyme:promoter complexes (Feklistov et al., 2014). These efforts have allowed insights into the processes of both promoter recognition and DNA strand separation for σ70 holoenzyme (Zhang et al., 2012), and recently, for two holoenymes containing mycobacterial ECF σ factors (Li et al., 2019, Lin et al., 2019). Three decades ago, we predicted that conserved aromatic amino acids σ region 2.3 (a TYATWW motif in σA) would be involved in DNA strand separation (Helmann & Chamberlin, 1988), and subsequently demonstrated that mutations of the corresponding aromatic amino acids formed holoenzymes specifically defective in the DNA-melting step accompanying open complex formation (Juang & Helmann, 1994). Gratifyingly, these interactions are now understood to be central for DNA-melting and the accompanying sequence-selective recognition of the non-template strand during the transition from the initial closed to the open complex (Murakami & Darst, 2003, Bae et al., 2015). The situation with ECF σ factors is somewhat more complicated, and also involves an adjacent loop region (Campagne et al., 2014), but generally follows a process reminiscent of that for σA holoenzyme (Li et al., 2019, Lin et al., 2019). This is just one example of how structural studies have helped inform our understanding of RNA polymerase, and its interactions with its template, substrates, accessary subunits and regulators, and transcription factors (Feklistov et al., 2014).

The advent of high throughput DNA sequencing methods has also drastically altered our perspective on σ factors and their diversity. The original dideoxy-method of Sanger held sway for over 25 years as the dominant technology, although the introduction of fluorescent chain-terminators and automated, capillary-based sequencing machines has spared individual investigators from the tedium of pouring and running sequencing gels. The subsequent development of new, next-generation sequencing technologies has vastly increased our access to the universe of genetic information (Loman & Pallen, 2015, Shendure et al., 2017). This immense treasure-trove of information has enabled scientists to answer questions in ways that could scarcely have been dreamt of in prior decades, a time when σ factors were visualized by the small cadre of researchers in this area as bands on an SDS-PAGE gel that correlated with distinct transcriptional activities.

Bacterial genomics has led to the recognition of the ECF σ family as a very large and diverse group of σ factors. In a seminal analysis of the family, the group of Thorsten Mascher determined that these proteins form a “third pillar”, together with one- and two-component regulator systems, of bacterial gene regulation (Staron et al., 2009). This paper also led to the first iteration of the current ECF σ classification system based on phylogenomics (Fig. 3). Analysis of nearly 3000 ECF σ sequences identified 43 distinct groups (designated ECF01 through ECF43) that encompassed 2/3 of the available sequences, with the remaining forming many smaller clusters (Staron et al., 2009). This classification scheme has since grown to ~100 distinct groups of ECF σ factors, as defined based on their protein sequences, genomic context, and target promoter sequences (Pinto & Mascher, 2016).

Despite this large expansion of the σ factor family tree, it remains likely that there are branches yet to be discovered (Mascher, 2013). Moreover, the diversity of gene regulation mechanisms in phage never ceases to amaze, and there are likely divergent regulators in these systems that function as σ factors, through a σ-like mechanism, or by modifying host σ activity in interesting ways (Tabib-Salazar et al., 2019). We also described an unusual “split” σ in B. subtilis, in which two polypeptides (one with σ region 2 like functions, and the other corresponding more closely to region 4) cooperate in promoter recognition and activation (MacLellan et al., 2009). This is reminiscent of the earliest efforts to define alternative σ factors in which it was noted that late transcription in B. subtilis phage SP01 required the cooperation of two polypeptides (Tijan & Pero, 1976). With the current explosion of DNA sequence information, it remains possible that there are new branches of the σ70 family tree, or even new types of σ like regulators entirely.

This brief survey of the unfolding story of nucleic acid polymerases over the last ~60 years, and of bacterial σ factors since their discovery 50 years ago, provides one example of how changing times and new technologies have dictated and constrained the dominant approaches during each phase of discovery. For the first half of this period, nucleic acid enzymology generally, and the early studies of RNA polymerase specifically, were driven by classical biochemical approaches developed by Arthur Kornberg and his contemporaries, including Paul Berg and his student Mike Chamberlin. Key early contributions from Jan Pero, Richard Losick, Richard Burgess, and their scientific progeny set the stage for the next major leaps forward, enabled and facilitated by the new technology of dideoxy-based (Sanger) sequencing. The merging of biochemical studies with genetic and molecular biology approaches was foundational for this next phase, including key contributions from Carol Gross, Mark Buttner, Tim Donohue, and many others. The newest phase can again be traced to a change in enabling technologies: the explosion of sequence information from high-throughput sequencing has led to insights into the vast diversity of ECF σ factors, and motivated efforts to harness this diversity for applications in synthetic biology (Pinto et al., 2019, Pinto et al., 2018, Rhodius et al., 2013).

Acknowledgements

I thank my many students for their contributions to our laboratory’s work on transcriptional regulation mechanisms, and apologize to those not explicitly cited. Work in the area of bacterial transcription is enriched by excellent colleagues, and only a subset of their contributions are explicitly acknowledged here. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R35GM122461) to JDH.

REFERENCES

- Aiyar SE, Helmann JD & deHaseth PL, (1994) A mismatch bubble in double-stranded DNA suffices to direct precise transcription initiation by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem 269: 13179–13184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai K, Yamaguchi H, Kang CM, Yoshida K, Fujita Y & Sadaie Y, (2003) DNA microarray analysis of Bacillus subtilis sigma factors of extracytoplasmic function family. FEMS Microbiol Lett 220: 155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae B, Feklistov A, Lass-Napiorkowska A, Landick R & Darst SA, (2015) Structure of a bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme open promoter complex. Elife 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkotoky S & Murali A, (2018) The highly efficient T7 RNA polymerase: A wonder macromolecule in biological realm. Int J Biol Macromol 118: 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess RR, (1969) Separation and characterization of the subunits of ribonucleic acid polymerase. J Biol Chem 244: 6168–6176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess RR, Travers AA, Dunn JJ & Bautz EK, (1969) Factor stimulating transcription by RNA polymerase. Nature 221: 43–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton Z, Burgess RR, Lin J, Moore D, Holder S & Gross CA, (1981) The nucleotide sequence of the cloned rpoD gene for the RNA polymerase sigma subunit from E. coli K12. Nucleic Acids Res 9: 2889–2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher BG & Helmann JD, (2006) Identification of Bacillus subtilis σW-dependent genes that provide intrinsic resistance to antimicrobial compounds produced by Bacilli. Mol Microbiol 60: 765–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner MJ, Smith AM & Bibb MJ, (1988) At least three different RNA polymerase holoenzymes direct transcription of the agarase gene (dagA) of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Cell 52: 599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagne S, Marsh ME, Capitani G, Vorholt JA & Allain FH, (2014) Structural basis for −10 promoter element melting by environmentally induced sigma factors. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21: 269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Bernat BA, Wang Z, Armstrong RN & Helmann JD, (2001) FosB, a cysteine-dependent fosfomycin resistance protein under the control of σW, an extracytoplasmic-function sigma factor in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 183: 2380–2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M & Helmann JD, (2004) The Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic-function σX factor regulates modification of the cell envelope and resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides. J Bacteriol 186: 1136–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Kobel PA, Morshedi MM, Wu MF, Paddon C & Helmann JD, (2002a) Defining the Bacillus subtilis σW regulon: a comparative analysis of promoter consensus search, run-off transcription/macroarray analysis (ROMA), and transcriptional profiling approaches. J Mol Biol 316: 443–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Wang T, Ye R & Helmann JD, (2002b) Antibiotics that inhibit cell wall biosynthesis induce expression of the Bacillus subtilis σW and σM regulons. Mol Microbiol 45: 1267–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin M, (1976) RNA polymerase—an overview In: Polymerase RNA. Losick R & Chamberlin M (eds). CSH Monographs, pp. 17–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin M & Berg P, (1962) Deoxyribonucleic acid-directed synthesis of ribonucleic acid by an enzyme from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 48: 81–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin M, McGrath J & Waskell L, (1970) New RNA polymerase from Escherichia coli infected with bacteriophage T7. Nature 228: 227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin MJ, (1974) The selectivity of transcription. Annu Rev Biochem 43: 721–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chater KF, Bruton CJ, Plaskitt KA, Buttner MJ, Mendez C & Helmann JD, (1989) The developmental fate of S. coelicolor hyphae depends upon a gene product homologous with the motility sigma factor of B. subtilis. Cell 59: 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YF & Helmann JD, (1992) Restoration of motility to an Escherichia coli fliA flagellar mutant by a Bacillus subtilis sigma factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89: 5123–5127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danson AE, Jovanovic M, Buck M & Zhang X, (2019) Mechanisms of sigma(54)-Dependent Transcription Initiation and Regulation. J Mol Biol. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lucia P & Cairns J, (1969) Isolation of an E. coli strain with a mutation affecting DNA polymerase. Nature 224: 1164–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour YS, Landick R & Donohue TJ, (2008) Organization and evolution of the biological response to singlet oxygen stress. J Mol Biol 383: 713–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiamphungporn W & Helmann JD, (2008) The Bacillus subtilis σM regulon and its contribution to cell envelope stress responses. Mol Microbiol 67: 830–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feklistov A, Sharon BD, Darst SA & Gross CA, (2014) Bacterial sigma factors: a historical, structural, and genomic perspective. Annu Rev Microbiol 68: 357–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox TD, Losick R & Pero J, (1976) Regulatory gene 28 of bacteriophage SPO1 codes for a phage-induced subunit of RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol 101: 427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox TD & Pero J, (1974) New phage-SPO1-induced polypeptides associated with Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 71: 2761–2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrick K & Helmann JD, (1997) RNA polymerase sigma factor determines start-site selection but is not required for upstream promoter element activation on heteroduplex (bubble) templates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94: 4982–4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardella T, Moyle H & Susskind MM, (1989) A mutant Escherichia coli sigma 70 subunit of RNA polymerase with altered promoter specificity. J Mol Biol 206: 579–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiduschek EP & Kassavetis GA, (2010) Transcription of the T4 late genes. Virol J 7: 288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiduschek EP, Nakamoto T & Weiss SB, (1961) The enzymatic synthesis of RNA: complementary interaction with DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 47: 1405–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman MZ, Glenn JS, Singer VL & Chamberlin MJ, (1984) Isolation of sigma-28-specific promoters from Bacillus subtilis DNA. Gene 32: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman MZ, Wiggs JL & Chamberlin MJ, (1981) Nucleotide sequences of two Bacillus subtilis promoters used by Bacillus subtilis sigma-28 RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res 9: 5991–6000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitt MA, Wang LF & Doi RH, (1985) A strong sequence homology exists between the major RNA polymerase sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 260: 7178–7185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribskov M & Burgess RR, (1986) Sigma factors from E. coli, B. subtilis, phage SP01, and phage T4 are homologous proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 14: 6745–6763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross CA, Blattner FR, Taylor WE, Lowe PA & Burgess RR, (1979) Isolation and characterization of transducing phage coding for sigma subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76: 5789–5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AD, Erickson JW & Gross CA, (1984) The htpR gene product of E. coli is a sigma factor for heat-shock promoters. Cell 38: 383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunberg-Manago M, (1989) Recollections on studies of polynucleotide phosphorylase: a commentary on ‘Enzymic Synthesis of Polynucleotides. I. Polynucleotide Phosphorylase of Azobacter vinelandii’. Biochim Biophys Acta 1000: 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guariglia-Oropeza V & Helmann JD, (2011) Bacillus subtilis σV confers lysozyme resistance by activation of two cell wall modification pathways, peptidoglycan O-acetylation and D-alanylation of teichoic acids. J Bacteriol 193: 6223–6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager DA & Burgess RR, (1980) Elution of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels, removal of sodium dodecyl sulfate, and renaturation of enzymatic activity: results with sigma subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase, wheat germ DNA topoisomerase, and other enzymes. Anal Biochem 109: 76–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldenwang WG, Lang N & Losick R, (1981) A sporulation-induced sigma-like regulatory protein from B. subtilis. Cell 23: 615–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldenwang WG & Losick R, (1979) A modified RNA polymerase transcribes a cloned gene under sporulation control in Bacillus subtilis. Nature 282: 256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldenwang WG & Losick R, (1980) Novel RNA polymerase sigma factor from Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77: 7000–7004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmann JD, (2002) The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Adv Microb Physiol 46: 47–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmann JD, (2016) Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors and defense of the cell envelope. Curr Opin Microbiol 30: 122–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmann JD & Chamberlin MJ, (1987) DNA sequence analysis suggests that expression of flagellar and chemotaxis genes in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium is controlled by an alternative sigma factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84: 6422–6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmann JD & Chamberlin MJ, (1988) Structure and function of bacterial sigma factors. Annu Rev Biochem 57: 839–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmann JD, Marquez LM & Chamberlin MJ, (1988a) Cloning, sequencing, and disruption of the Bacillus subtilis sigma 28 gene. J Bacteriol 170: 1568–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmann JD, Masiarz FR & Chamberlin MJ, (1988b) Isolation and characterization of the Bacillus subtilis sigma 28 factor. J Bacteriol 170: 1560–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman J, Wong PK, Sei K, Keener J & Kustu S, (1985) Products of nitrogen regulatory genes ntrA and ntrC of enteric bacteria activate glnA transcription in vitro: evidence that the ntrA product is a sigma factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82: 7525–7529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho TD, Hastie JL, Intile PJ & Ellermeier CD, (2011) The Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function sigma factor σV is induced by lysozyme and provides resistance to lysozyme. J Bacteriol 193: 6215–6222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Fredrick KL & Helmann JD, (1998) Promoter recognition by Bacillus subtilis σW: autoregulation and partial overlap with the σX regulon. J Bacteriol 180: 3765–3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Gaballa A, Cao M & Helmann JD, (1999) Identification of target promoters for the Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function σ factor, σW. Mol Microbiol 31: 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X & Helmann JD, (1998) Identification of target promoters for the Bacillus subtilis σX factor using a consensus-directed search. J Mol Biol 279: 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz J, (2005) The discovery of RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem 280: 42477–42485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaehning JA, Wiggs JL & Chamberlin MJ, (1979) Altered promoter selection by a novel form of Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76: 5470–5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R, Frederick JP, Huang EY, Burke KE, Mauger DM, Andrianova EA, Farlow SJ, Siddiqui S, Pimentel J, Cheung-Ong K, McKinney KM, Kohrer C, Moore MJ & Chakraborty T, (2018) MicroRNAs Enable mRNA Therapeutics to Selectively Program Cancer Cells to Self-Destruct. Nucleic Acid Ther 28: 285–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang YL & Helmann JD, (1994) A promoter melting region in the primary sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis. Identification of functionally important aromatic amino acids. J Mol Biol 235: 1470–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston AW, Subramanian C, Rock CO & Helmann JD, (2011) A σW-dependent stress response in Bacillus subtilis that reduces membrane fluidity. Mol Microbiol 81: 69–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo BM, Rhodius VA, Nonaka G, deHaseth PL & Gross CA, (2009) Reduced capacity of alternative sigmas to melt promoters ensures stringent promoter recognition. Genes Dev 23: 2426–2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg A, (1989) The early history of DNA polymerase: a commentary on ‘Enzymic Synthesis of Deoxyribonucleic Acid’. Biochim Biophys Acta 1000: 53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresge N, Simoni RD & Hill RL, (2006) The Discovery and Isolation of RNA Polymerase by Jerard Hurwitz. J. Biol. Chem. 281: e12. [Google Scholar]

- Landick R, Vaughn V, Lau ET, VanBogelen RA, Erickson JW & Neidhardt FC, (1984) Nucleotide sequence of the heat shock regulatory gene of E. coli suggests its protein product may be a transcription factor. Cell 38: 175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G & Pero J, (1981) Conserved nucleotide sequences in temporally controlled bacteriophage promoters. J Mol Biol 152: 247–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman IR, (2003) Discovery of DNA polymerase. J Biol Chem 278: 34733–34738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Fang C, Zhuang N, Wang T & Zhang Y, (2019) Structural basis for transcription initiation by bacterial ECF sigma factors. Nat Commun 10: 1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Mandal S, Degen D, Cho MS, Feng Y, Das K & Ebright RH, (2019) Structural basis of ECF-sigma-factor-dependent transcription initiation. Nat Commun 10: 710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loman NJ & Pallen MJ, (2015) Twenty years of bacterial genome sequencing. Nat Rev Microbiol 13: 787–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonetto M, Gribskov M & Gross CA, (1992) The sigma 70 family: sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships. J Bacteriol 174: 3843–3849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonetto MA, Brown KL, Rudd KE & Buttner MJ, (1994) Analysis of the Streptomyces coelicolor sigE gene reveals the existence of a subfamily of eubacterial RNA polymerase sigma factors involved in the regulation of extracytoplasmic functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 7573–7577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losick R & Pero J, (1981) Cascades of Sigma factors. Cell 25: 582–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losick R & Pero J, (2018) For Want of a Template. Cell 172: 1146–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losick R & Sonenshein AL, (1969) Change in the template specificity of RNA polymerase during sporulation of Bacillus subtilis. Nature 224: 35–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losick R, Youngman P & Piggot PJ, (1986) Genetics of endospore formation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Genet 20: 625–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Asai K, Sadaie Y & Helmann JD, (2010) Transcriptomic and phenotypic characterization of a Bacillus subtilis strain without extracytoplasmic function sigma factors. J Bacteriol 192: 5736–5745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y & Helmann JD, (2009) Extracytoplasmic function sigma factors with overlapping promoter specificity regulate sublancin production in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 191: 4951–4958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y & Helmann JD, (2012) Analysis of the role of Bacillus subtilis σM in beta-lactam resistance reveals an essential role for c-di-AMP in peptidoglycan homeostasis. Mol Microbiol 83: 623–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLellan SR, Guariglia-Oropeza V, Gaballa A & Helmann JD, (2009) A two-subunit bacterial sigma-factor activates transcription in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 21323–21328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascher T, (2013) Signaling diversity and evolution of extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Curr Opin Microbiol 16: 148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascher T, Hachmann AB & Helmann JD, (2007) Regulatory overlap and functional redundancy among Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function sigma factors. J Bacteriol 189: 6919–6927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHenry CS, (1991) DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. Components, structure, and mechanism of a true replicative complex. J Biol Chem 266: 19127–19130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeske AJ, Sham LT, Kimsey H, Koo BM, Gross CA, Bernhardt TG & Rudner DZ, (2015) MurJ and a novel lipid II flippase are required for cell wall biogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: 6437–6442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick MJ, (1993) In a class of its own--the RNA polymerase sigma factor sigma 54 (sigma N). Mol Microbiol 10: 903–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra P, Ghosh G, Hafeezunnisa M & Sen R, (2017) Rho Protein: Roles and Mechanisms. Annu Rev Microbiol 71: 687–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran CP Jr., Lang N & Losick R, (1981) Nucleotide sequence of a Bacillus subtilis promoter recognized by Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase containing sigma 37. Nucleic Acids Res 9: 5979–5990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey MR & Loewen PC, (1989) Nucleotide sequence of katF of Escherichia coli suggests KatF protein is a novel sigma transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res 17: 9979–9991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami KS & Darst SA, (2003) Bacterial RNA polymerases: the wholo story. Curr Opin Struct Biol 13: 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa S, (1980) The pursuit of a hobby. Annu Rev Biochem 49: 1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pero J, Tjian R, Nelson J & Losick R, (1975) In vitro transcription of a late class of phage SP01 genes. Nature 257: 248–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto D, Durr F, Froriep F, Araujo D, Liu Q & Mascher T, (2019) Extracytoplasmic Function sigma Factors Can Be Implemented as Robust Heterologous Genetic Switches in Bacillus subtilis. iScience 13: 380–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto D & Mascher T, (2016) The ECF classification: a phylogenetic reflection of the regulatory diversity in the extracytoplasmic function σ factor protein family, in “Stress and Environmental Regulation of Gene Expression and Adaptation in Bacteria”, 2 Volume Set (ed. de Bruijn John Wiley & Sons), pp. 64–96. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto D, Vecchione S, Wu H, Mauri M, Mascher T & Fritz G, (2018) Engineering orthogonal synthetic timer circuits based on extracytoplasmic function sigma factors. Nucleic Acids Res 46: 7450–7464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribnow D, (1975) Nucleotide sequence of an RNA polymerase binding site at an early T7 promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 72: 784–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J & Helmann JD, (2001) The −10 region is a key promoter specificity determinant for the Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic-function sigma factors σX and σW. J Bacteriol 183: 1921–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodius VA, Segall-Shapiro TH, Sharon BD, Ghodasara A, Orlova E, Tabakh H, Burkhardt DH, Clancy K, Peterson TC, Gross CA & Voigt CA, (2013) Design of orthogonal genetic switches based on a crosstalk map of sigmas, anti-sigmas, and promoters. Mol Syst Biol 9: 702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodius VA, Suh WC, Nonaka G, West J & Gross CA, (2006) Conserved and variable functions of the σE stress response in related genomes. PLoS Biol 4: e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JW, (1969) Termination factor for RNA synthesis. Nature 224: 1168–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F, Nicklen S & Coulson AR, (1977) DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 74: 5463–5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shendure J, Balasubramanian S, Church GM, Gilbert W, Rogers J, Schloss JA & Waterston RH, (2017) DNA sequencing at 40: past, present and future. Nature 550: 345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegele DA, Hu JC, Walter WA & Gross CA, (1989) Altered promoter recognition by mutant forms of the sigma 70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol 206: 591–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staron A, Sofia HJ, Dietrich S, Ulrich LE, Liesegang H & Mascher T, (2009) The third pillar of bacterial signal transduction: classification of the extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor protein family. Mol Microbiol 74: 557–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier FW, Rosenberg AH, Dunn JJ & Dubendorff JW, (1990) Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol 185: 60–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabib-Salazar A, Mulvenna N, Severinov K, Matthews SJ & Wigneshweraraj S, (2019) Xenogeneic Regulation of the Bacterial Transcription Machinery. J Mol Biol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjian R & Pero J, (1976) Bacteriophage SP01 regulatory proteins directing late gene transcription in vitro. Nature 262: 753–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers AA & Burgess RR. (1969) Cyclic re-use of the RNA polymerase sigma factor. Nature 222: 537–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Li Y, Wang Y, Shi C, Li C, Li Q & Linhardt RJ, (2018) Bacteriophage T7 transcription system: an enabling tool in synthetic biology. Biotechnol Adv 36: 2129–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JD & Crick FH, (1953) Molecular structure of nucleic acids; a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature 171: 737–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggs JL, Bush JW & Chamberlin MJ, (1979) Utilization of promoter and terminator sites on bacteriophage T7 DNA by RNA polymerases from a variety of bacterial orders. Cell 16: 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggs JL, Gilman MZ & Chamberlin MJ, (1981) Heterogeneity of RNA polymerase in Bacillus subtilis: evidence for an additional sigma factor in vegetative cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78: 2762–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Feng Y, Chatterjee S, Tuske S, Ho MX, Arnold E & Ebright RH, (2012) Structural basis of transcription initiation. Science 338: 1076–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuber P, Healy J, Carter HL 3rd, Cutting S, Moran CP Jr. & Losick R, (1989) Mutation changing the specificity of an RNA polymerase sigma factor. J Mol Biol 206: 605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]