Abstract

Mosaic loss of Y chromosome (mLOY) is the most frequently detected somatic copy number alteration in leukocytes of men. In this study, we investigate blood cell counts as a potential mechanism linking mLOY to disease risk in 206,353 UK males. Associations between mLOY, detected by genotyping arrays, and blood cell counts were assessed by multivariable linear models adjusted for relevant risk factors. Among the participants, mLOY was detected in 39,809 men. We observed associations between mLOY and reduced erythrocyte count (−0.009 [−0.014, −0.005] × 1012 cells/L, p = 2.75 × 10−5) and elevated thrombocyte count (5.523 [4.862, 6.183] × 109 cells/L, p = 2.32 × 10−60) and leukocyte count (0.218 [0.198, 0.239] × 109 cells/L, p = 9.22 × 10−95), particularly for neutrophil count (0.174 × [0.158, 0.190]109 cells/L, p = 1.24 × 10−99) and monocyte count (0.021 [0.018 to 0.024] × 109 cells/L, p = 6.93 × 10−57), but lymphocyte count was less consistent (0.016 [0.007, 0.025] × 109 cells/L, p = 8.52 × 10−4). Stratified analyses indicate these associations are independent of the effects of aging and smoking. Our findings provide population-based evidence for associations between mLOY and blood cell counts that should stimulate investigation of the underlying biological mechanisms linking mLOY to cancer and chronic disease risk.

Subject terms: Genetics, Biomarkers, Risk factors

Introduction

Recently, large molecular epidemiology studies have shown that hematopoietic cells can undergo postzygotic mutations resulting in somatic copy number alterations, which can give rise to daughter cells with the same genomic aberration. Clonal expansion of cells bearing a somatic mutation results in clonal mosaicism1. Clonal mosaicism can be driven by somatic mutations affecting genes frequently mutated in myelodysplastic disease (referred to as clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP))2 or be the result of acquired copy number aberrations. The most frequently detected somatic copy number alteration in circulating leukocytes is mosaic loss of the Y chromosome (mLOY) in males3–5. The prevalence of mLOY is age-related, increasing substantially after age 50 in men. Likewise, CHIP is common in the elderly, with recent evidence suggesting CHIP and mLOY may co-occur6. Exposure to cigarette smoking4,7 has also been well established as a risk factor for mLOY and recently, early evidence suggests that air pollution could also be associated with mLOY8. Epidemiologic studies have uncovered potential associations between mLOY and increased risk of cancer3–5, neurodegenerative diseases9, and cardiovascular diseases10,11. Similarly, CHIP has been associated with select cancers and cardiovascular disease2. Although common germline variants near important cell-cycle regulation and cancer susceptibility genes have been identified through genome-wide association studies of mLOY4,12, the underlying biologic mechanisms linking mLOY to chronic disease risk are likely complex.

We investigated possible associations between mLOY and clinical measures, here the composition of the classical hematologic compartments in the UK Biobank, which has available genomic and blood cell count data on over 220,000 men, providing a large well-characterized population to investigate these questions. We performed multivariable, stratified and mediation analyses to evaluate the association of mLOY with blood cell count and distribution. Our study provides a unique, population-based investigation of changes in blood cell counts associated with a somatic mutation. Our findings indicate robust associations between mLOY and leukocyte, erythrocyte and thrombocyte counts, independent of age and cigarette smoking.

Methods

The current analyses were extension of our previous studies5,13,14 which included population-based data from 223,336 males between age 37 and 73 recruited between 2007 to 2010 from the UK Biobank15,16. After providing informed consent, each participant provided a blood sample, answered a detailed health and lifestyle questionnaire, and had physical measurements taken. Collected blood was held at 4 °C and sent to a central processing laboratory in temperature-controlled boxes. Samples were processed, aliquoted and cryopreserved at −80 °C or −196 °C. One tube of blood was loaded on a Beckman Coulter LH750 to provide direct measurement of various blood cell counts and indices including but not limiting to hematocrit, plateletcrit, mean corpuscular volume, hemoglobin, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, mean sphered cell volume, mean platelet volume, platelet distribution width, immature reticulocyte fraction, and high light scatter reticulocyte proportion.

Blood-derived DNA from UK Biobank men was extracted starting early 2013 and genotyped on Affymetrix UK BiLEVE or UK Biobank Axiom arrays. mLOY was measured by two different methods. The first measure of mLOY was made by examining the median log R ratio (mLRR) of 691 single nucleotide polymorphisms spanning the male specific region of the Y chromosome. LRR is a measure of probe signal intensity on the genotyping array with negative values across contiguous variants indicating evidence for a copy number loss and positive values indicating copy number gain. Men with mLRR > 0.15 could possibly have a mosaic gain of Y chromosome or a constitutional extra copy of the Y chromosome (XYY syndrome) and were removed (205 men, 0.09%). We also apply the methods proposed by Thompson et al.14 to call dichotomized mLOY. For clarity, we use the term mLOY for dichotomized mLOY calls by Thompson et al.

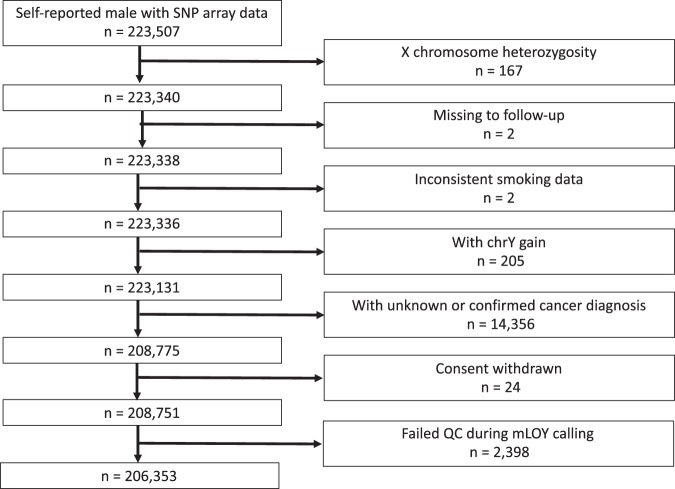

Our final analytical set included 206,353 self-reported men who reported no prior cancer history at recruitment (n = 14,356 excluded), did not have X chromosome heterozygosity (n = 167 excluded), had consistent smoking data (n = 2 excluded), were without evidence of copy number gains of Y chromosome (n = 205 excluded) and passed quality control during the dichotomized mLOY detection step (n = 2,394 excluded) as shown in Fig. 1. Multivariable linear regression was employed to identify associations between lifestyle factors, mLOY and blood cell counts. Factors which might influence blood cell counts (smoking17, BMI18, alcohol consumption19, diabetes20, hypertension21, and hypoercholesterolemia22) were included in multivariable models. For interaction between smoking and mLOY, we fit models with mLRR, 3-level smoking status (never, former, current), interaction terms between mLRR and smoking, and all other aforementioned covariates. We adjusted for continuous age, age squared13, race/ethnicity, smoking, alcohol consumption, continuous body mass index (BMI), self-reported diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. When modeling mLRR, we applied the following formula to calculate standardized mLRR for easier interpretation of the regression coefficient. We first subtracted mean of raw mLRR (mLRRr) from all raw mLRR, divided the difference by standard deviation (S.D.) of mLRRr, and flipped the sign (to have effect estimates in the same direction as the dichotomous mLOY estimates).

Figure 1.

Number of participants. The number of participants excluded by each criterion was shown.

A 25-level smoking status variable was created according to prior literature13 and used in the majority of our models. In brief, a detailed smoking history variable was created by combining information on baseline smoking status, smoking intensity, time since quitting, and type of tobacco product smoked (i.e., cigarettes or cigars/pipes). Indicator variables were created for each category and “never smokers” were used as the reference group. After accounting for skip patterns, a small percentage of respondents were missing one or more pieces of information. Because we had some, but not complete, smoking information on these respondents we created a number of indicator variables for each of the partial missing categories. Alcohol consumption was coded in 7 levels (never, former, occasional, 1–3 drink/month, 1–2 drink/week, 3–4 drink/week) according to the history and frequency of consumption. Continuous BMI was used in most models while a 5-level BMI defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) was also presented for reference. All missing data in categorical variables were coded as ‘missing’ and included in the analysis. A significance level was set at 0.001 to account for multiple comparisons (0.05/50 independent tests for all indicator variables). To evaluate the effect of any potential residual confounding from smoking and age in the reported association between mLOY and blood cell counts, we conducted a sensitivity analysis restricted to strata of ever or never smokers and individuals older or younger than 65 years old. We chose 65 years old because the prevalence of mLOY increased exponentially between 60 to 70 years old even for never smokers (Fig. S1).

A polygenic risk score (PRS) was created to estimate the effect of genetic contributors to mLOY. The PRS was calculated by scoring risk alleles in 156 variants previously found to be associated with mLOY risk using the formula:

i denotes an individual while j denotes a SNP being scored. The number of risk alleles of each variant (SNPij) were weighted by reported estimates for log odds ratio of risk alleles (β)23. Then, blood cell counts and other indices were regressed against the PRS instrumental variable to investigate for potential associations between mLOY PRS and blood counts. Mediation analyses were conducted to estimate the direct and indirect effect among smoking, mLOY, and blood cell counts while controlling for BMI, ethnicity, alcohol consumption, diabetes, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia using the “mediation” package in R24.

Finally, we performed reciprocal Mendelian randomization (MR) on previously reported mLOY-associated SNPs as well as blood cell count-associated SNPs obtained from PhenoScanner25,26. We queried for respective blood cell counts in PhenoScanner and discarded multi-allelic SNPs. The final list of SNPs included 270 for leukocyte count27–39, 1,888 for erythrocyte count29,31–36,39–48, and 662 for thrombocyte count29,31–36,44,49–55. Estimation of causal association was carried out by the “MendelianRandomization” package56. All statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.5.2 and plots were created using the “ggplot2”57 and “sjPlot”58 packages.

Ethical approval

The UK Biobank received ethical approval from the research ethics committee (REC reference for UK Biobank 21552) and all participants provided signed informed consent at enrollment and all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations. All data used in this analysis is available through application to the UK Biobank.

Results

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1 based on their mLOY status. Among the 206,353 UK Biobank male subjects in our analytic set, we detected mLOY in 39,809 men (19.29%). Compared to participants without mLOY, those with mLOY were older (6.683 [6.598, 6.768] years, p < 5 × 10−324), more likely to be white (OR = 2.822 [2.560, 3.118], 4.014 [3.464, 4.682] compared to Asian and Black, respectively. p < 5 × 10−324 for both), more likely to smoke (OR = 1.588 [1.551, 1.627] and 1.973 [1.910, 2.038] for former and current compared to never smokers, respectively. p < 5 × 10−324 for both), more likely to consume alcohol (OR = 1.451 [1.324, 1.591] and 1.326 [1.234, 1.426] for former and current compared to never drinkers, p = 8.88 × 10−16 and 4.00 × 10−15, respectively), less likely to have BMI > 35 (OR = 0.645 [0.513, 0.820], p < 5 × 10−324), more likely to have diabetes (OR = 1.121 [1.072, 1.171], p = 6.71 × 10−7), hypertension (OR = 1.344 [1.314, 1.376], p < 5 × 10−324), and hypercholesterolemia (OR = 1.509 [1.468, 1.552]], p < 5 × 10−324). As expected, as individuals age, the prevalence of mLOY increased exponentially (Fig. S1). There was no significant difference for mLOY prevalence by assessment center and region (Table S1). In univariable analyses, we detected associations (p < 0.001) between mLOY and counts of six blood cell populations including leukocytes, erythrocytes, thrombocytes, lymphocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils (Fig. 2). We examined possible confounding by immune-related diseases identified in inpatient records and did not identify any statistically significant association between these diseases and mLOY (Table S2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by mLOY status.

| Characteristics | Normal | mLOY | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | 166548 (80.7) | 39809 (19.3) | NA |

| Age (mean,SD) | 55.199 (8.168) | 61.882 (5.784) | <5 × 10−324 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 155443 (80) | 38790 (20) | Ref |

| Mixed | 922 (90.5) | 97 (9.5) | <5 × 10−324 |

| Asian | 4932 (91.9) | 436 (8.1) | <5 × 10−324 |

| Black | 2914 (94.2) | 181 (5.8) | <5 × 10−324 |

| Other | 1648 (92.3) | 138 (7.7) | <5 × 10−324 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 86007 (84.8) | 15474 (15.2) | Ref |

| Former | 60851 (77.8) | 17388 (22.2) | <5 × 10−324 |

| Current | 19072 (73.8) | 6770 (26.2) | <5 × 10−324 |

| Alcohol drinking | |||

| Never | 4877 (84.7) | 883 (15.3) | Ref |

| Former | 5660 (79.2) | 1487 (20.8) | 8.88 × 10−16 |

| Current | 155837 (80.6) | 37408 (19.4) | 4.00 × 10−15 |

| Body mass index | |||

| 18.5- | 339 (78.3) | 94 (21.7) | 0.279 |

| 18.5to25 | 39733 (80.4) | 9702 (19.6) | Ref |

| 25to30 | 80774 (80.3) | 19853 (19.7) | 0.636 |

| 30to35 | 32845 (81.4) | 7507 (18.6) | 1.08 × 10−4 |

| 35+ | 9864 (84.8) | 1767 (15.2) | <5 × 10−324 |

| Diseases | |||

| Diabetes | 9870 (79) | 2625 (21) | 6.71 × 10−7 |

| Hypertension | 48007 (77.4) | 14033 (22.6) | <5 × 10−324 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 24396 (74.9) | 8192 (25.1) | <5 × 10−324 |

Abbreviations: mLOY: mosaic loss of the Y chromosome.

aFisher’s exact test with mid-p method.

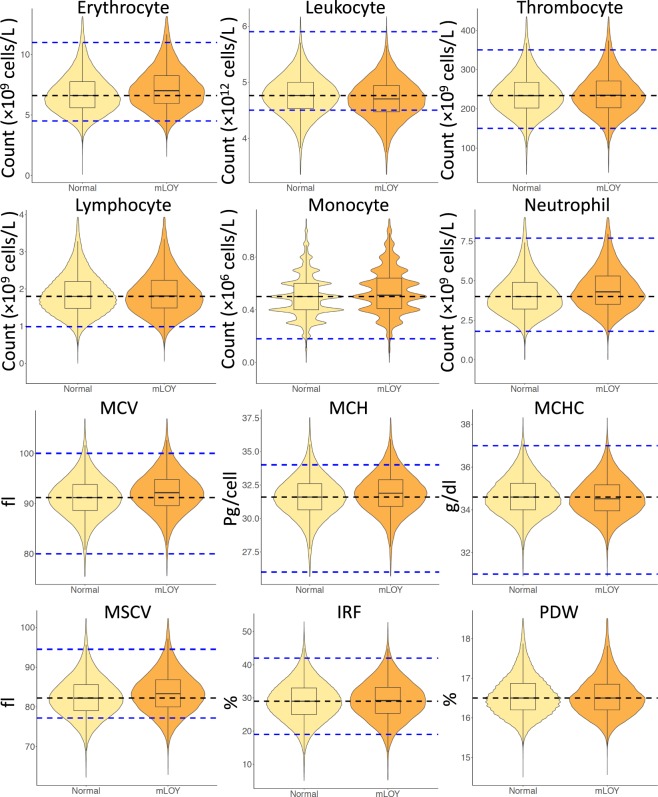

Figure 2.

Blood cell counts and indices by mLOY status. Various blood cell counts among men with different mLOY status were observed in univariate analyses. Yellow, Normal: men with normal chromosome Y; Orange, mLOY: men with mLOY. All displayed counts and indices had p < 0.001 when comparing between participants with or without mLOY. Black dashed lines: median count among normal individuals. Blue dashed lines: reference ranges from prior studies73–75. MCV: mean corpuscular volume. MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin. MCHC: mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration. MSCV: mean sphered corpuscular volume. IRF: immature reticulocyte fraction. PDW: platelet distribution width.

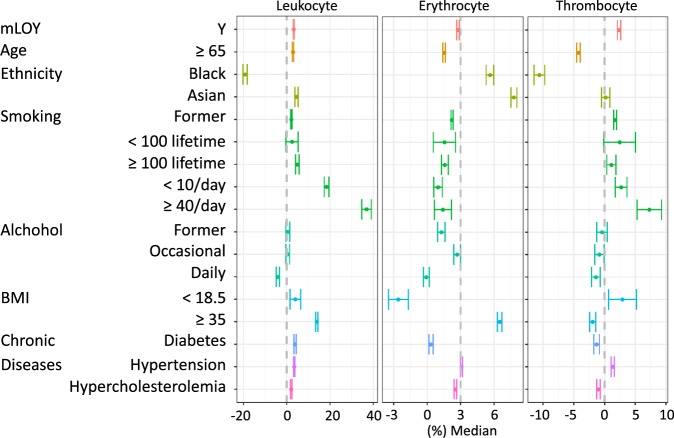

Multivariable analyses further confirmed this relationship between mLOY and blood cell count for erythrocytes (ORmLOY = −0.009 [−0.014, −0.005] × 1012 cells/L, pmLOY = 2.75 × 10−5; βmLRR = −0.009 [−0.010, −0.007] × 1012 cells/L, pmLRR = 8.73 × 10−23 for categorical mLOY and increase in each standard deviation of mLRR, respectively with all following estimates, 95% CIs, and p values reported in the same order), leukocytes (ORmLOY = 0.218 [0.198, 0.239] × 109 cells/L, pmLOY = 9.22 × 10−95; βmLRR = 0.058 [0.050 to 0.066] × 109 cells/L, pmLRR = 6.48 × 10−45) and thrombocytes (ORmLOY = 5.523 [4.862, 6.183] × 109 cells/L, pmLOY = 2.32 × 10−60; βmLRR = 2.321 [2.063, 2.579] × 109 cells/L, p = 2.41 × 10−69) (Fig. 3; Table S3). Among these blood cell count associations, mLOY was positively associated in all cases except for erythrocyte count where an inverse association was observed. For leukocyte populations, we observed elevated monocyte (ORmLOY = 0.021 [0.018, 0.024] × 109 cells/L, pmLOY = 6.93 × 10−57; βmLRR = 0.005 [0.004, 0.006] × 109 cells/L, pmLRR = 5.24 × 10−25) and neutrophil (ORmLOY = 0.174 [0.158, 0.190] × 109 cells/L, pmLOY = 1.24 × 10−99; βmLRR = 0.055 [0.048, 0.061] × 109 cells/L, pmLRR = 4.81 × 10−65) counts associated with mLOY (Table S4). We found inconsistent evidence for an overall association between mLOY and the overall lymphocyte count (ORmLOY = 0.016 [0.007, 0.025] × 109 cells/L, pmLOY = 8.52 × 10−4; βmLRR = −0.002 [−0.005, 0.002] × 109 cells/L, pmLRR = 0.345). While certain immune-related diseases were associated with blood cell counts (Tables S5 and S6), these diseases occurred in less than 1% of individuals and inclusion of these diseases did not significantly alter the estimates for mLOY and other risk factors. All observed blood count associations demonstrated a dose-response relationship which is evident in the mLRR results. The most prominent association was observed for neutrophil count in which men with mLOY had 1.74 × 108 more cells per liter compared to men without detectable mLOY. This is equivalent to an average increase of 4.153% in median neutrophil count among men without mLOY. As a comparison, among erythrocytes, the least associated blood cells, men with mLOY had 9 × 109 fewer erythrocyte per liter compared to men without mLOY, a decrease equivalent to 0.189% of the mean erythrocyte count in individuals without detectable mLOY.

Figure 3.

Relative impact of selected risk factors associated with leukocyte, erythrocyte, and thrombocyte counts. Multivariable linear regression models adjusted for age, age squared, race/ethnicity, smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index (continuous variable), diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. The reference group for categorical variables were no mLOY, Caucasian, never smoker, never drinker, 18.5 ≤ body mass index <25, no diabetes, no hypertension, no hypercholesterolemia. The point estimates, confidence interval, and p-values can be found in Table S1.

In addition to mLOY, the multivariable model also provided estimates for other potential factors associated with blood cell counts. Smokers who smoke >40 cigarettes per day had leukocyte count 36.91% higher than the median leukocyte count of never smokers with the elevation being evenly distributed across lymphocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils (Figs. 3 and S2). Black ethnicity was associated with 19.26% less leukocyte and 10.61% less thrombocyte compared to Whites, and the decrease in leukocyte count was more prominent among monocytes (19.80%) and neutrophils (32.67%), but relatively mild in lymphocytes (8.56%) suggesting a preferential activation of innate immunity. Alcohol consumption, even among daily drinkers, is mildly associated with blood cell counts, and the largest effect size was observed for decrease in leukocyte count (4.14%) when compared to never drinkers. Another factor associated with blood cell counts is body mass index (BMI) where having BMI greater than 35 was associated with increased leukocyte (13.60%), erythrocyte (2.92%), lymphocyte (16.61%), monocyte (16.86%), and neutrophil (11.72%) counts as well as decreased thrombocyte count (1.91%) compared to those with normal BMI (18.5 to 25).

As indicated in Table S7, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), a measure used to evaluate systemic inflammation in cancer patients, was found to be significantly elevated in men with mLOY (ORmLOY = 0.061 [0.045, 0.077], pmLOY = 2.98 × 10−14). The thrombocyte-lymphocyte ratio (TLR), a prognostic indicator for select cancer types59–62, was also found to be elevated in men with mLOY (ORmLOY = 1.288 [0.564, 2.012], pmLOY = 4.90 × 10−4). These mLOY associations with NLR and TLR showed robust dose response relationships and demonstrated significant trends with continuous mLRR (pmLRR = 1.39 × 10−33 and 3.31 × 10−32, respectively), suggesting robust relationships for mLOY with measures of both systematic inflammation and cancer prognosis.

To better understand the changes in erythrocyte and platelet counts, we also explored associations between mLOY and multiple erythrocyte indices. Both univariable (Fig. 2) and multivariable (Tables S8 and S9) regression on erythrocyte-related indices indicated that mLOY was associated with an increase in mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), immature reticulocyte fraction (IRF), mean sphered cell volume (MSCV), and high light scatter reticulocyte percentage (HLSRP) as well as decrease in hemoglobin (Hb).

To evaluate the potential effect of possible residual confounding from smoking, we conducted a sensitivity analysis restricted to strata of ever or never smokers. For leukocyte, erythrocyte, thrombocyte, monocyte, and neutrophil count, associations with mLOY and cell count remained significant, but the effect size was larger in ever smokers for all counts except thrombocyte count. (Tables S10–S13). Interestingly, lymphocyte count was only significantly increased in ever smokers. We further tested for interactions between mLOY and smoking on changes in blood cell count. mLRR was found to significantly interact with current smoking status in analyses of leukocyte (p = 5.06 × 10−31), thrombocyte (p = 4.18 × 10−6), lymphocyte (p = 5.25 × 10−11), and neutrophil (p = 2.26 × 10−25) count. Likewise, significant interactions between mLRR and former smoking status were also seen for leukocyte (p = 5.30 × 10−8) and neutrophil (p = 2.33 × 10−6) count. Inclusion of interaction terms modified the magnitude of association between mLRR and blood cell counts, but the direction of association between mLRR and cell counts remained the same except for lymphocyte count where the direction of association flipped in never smokers (Fig. S3). The associations between mLOY and NLR remained statically significant in both ever and never smokers (Table S14). We observed a stronger association between TLR and mLOY in never smokers (Table S15).

When stratified by age (<65 and ≥65), all blood cell counts remained significantly associated with mLOY at similar magnitude except for lymphocyte counts which were only marginally significant in the ≥65-year-old group (Tables S16–S19). As for NLR and TLR the magnitude of association between TLR and mLRR more than doubled in the ≥65 age group (Tables S20 and S21).

We also constructed a polygenic risk score using 156 SNPs previously found to be associated with mLOY23 as an instrumental variable to further investigate the association between mLOY and blood cell counts. As shown in Table S22, the mLOY PRS was significantly associated with leukocyte, erythrocyte, thrombocyte, monocyte, and neutrophil counts and the effect sizes closely mirrored those seen observationally for mLRR. Interestingly, the effect estimate for erythrocyte count was in the inverse direction for the mLOY PRS, suggesting potential non-genetic influences such as malnutrition or hypothyroidism could modify this association. The association between the mLOY PRS and blood cell counts was also examined in UK Biobank females and observed similar results as in males. We did not observe an association between mLOY PRS and overall lymphocyte count in the UK Biobank (Table S22).

In addition, we conducted reciprocal MR with SNPs associated with mLOY and blood cell counts (Table S23 and Fig. S4). We noted bi-directional effects for leukocyte count and thrombocyte count suggesting a potential shared biological process between mLOY and blood cell counts, although further studies are needed to confirm these findings. For erythrocyte counts, a potential effect was only observed from erythrocyte to mLOY, although the estimated effect size was small suggesting environmental or non-genetic contributors may also be important in this relationship.

Mediation analyses were also conducted to investigate whether mLOY acts as a potential mediator of the association between age or smoking and blood cell count. We found evidence suggesting most associations between age and blood cell counts were only partially mediated by mLOY (Tables S24 and S25). The estimated proportion of effect mediated by mLOY was less than 4%, suggesting any potential mediation effect of mLOY on age-related changes in blood cell counts only accounts for a small proportion of the total effect. We also found limited evidence suggesting mLOY mediated the association between smoking and blood cell counts (Tables S26 and S27) including leukocytes, erythrocytes, thrombocytes, monocytes and neutrophils with estimated proportion mediated of less than 2% of the total effect.

Discussion

We present evidence from a large cross-sectional study that demonstrates significant population-based associations between men with mosaic loss of the Y chromosome (mLOY) and circulating blood counts, as measured in a complete blood count. While differences observed remain within the range of expected healthy counts, some men with high proportions of mLOY had substantial deviations in blood cell counts, which could be a harbinger of chronic disease risk.

In a 2018 report by Loh et al., enrichment of autosomal mosaic events was observed among people with abnormal blood cell indices in UK Biobank63. For instance, the odds of having a copy number neutral mosaic event in chromosome 9p was 17.7 [10.2, 30.6] times higher among people with top 1% erythrocyte counts (p = 1.1 × 10−13). While Loh et al. detected an interesting association, the authors only examined the extreme 1% of blood cell indices which resulted in a small sample size and accordingly wide confidence intervals. Their analysis was also a univariable statistical test which did not take into account potential confounding by other factors. A recently published study on 57, 987 men in Biobank Japan also reported associations among mLOY, increased thrombocyte and leukocyte counts64. While the authors did not find statistically significant negative associations between erythrocyte counts and continuous mLRR in univariable models, effect estimates indicate men with mLOY trended toward a decreased erythrocyte count. In the current study, we modeled mLOY in both continuous and categorical measures and employed multiple strategies to prevent potential confounding including multivariable models adjusting for potential risk factors as well as polygenic risk scores and a Mendelian randomization framework which are less susceptible to confounding.

A proposed biologic mechanism relating mLOY to disease risk has been through alteration of the immune system and its response to multiple factors3,65. mLOY could be associated with differences in blood counts either as a consequence of the mosaicism or as a response to one or more exposures that drive development and maintenance of mLOY. In particular, neutrophils have been suggested to promote tumor initiation by releasing reactive oxygen species, reactive nitrogen species, and proteases, as well as promote progression by activating senescent cancer cells and suppressing CD8+ T cell-mediated immune responses66. The role of thrombocytes is complex: classically platelet counts can be elevated in inflammatory conditions or select pediatric cancers (e.g., neuroblastoma). The literature also supports the association of elevated platelet counts with lung cancer risk59. Still it is plausible that thrombocytes could contribute to tumor progression by stimulating angiogenesis67 and activating thrombosis-related inflammation68. In addition, observational studies have found that the composition of blood cells including neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and thrombocyte-lymphocyte ratio are associated with overall and disease-free survival in multiple cancers69.

Stratified analyses and inclusion of interaction terms in multivariable models demonstrated that smoking status interacts with mLOY and strengthened the association between mLOY and blood cell counts. Among the six blood cell types we reported, smoking status did not alter the directionality of associations between blood cell counts and mLOY except for lymphocytes. While mLOY was positively associated with lymphocyte counts in ever smokers, the association flipped in never smokers. This stark change in association along with a relatively mild association between mLOY and thrombocyte resulted in a larger effect size in association between TLR and mLOY in never smokers. Although high TLR has been suggested to be a prognostic biomarker reflecting systemic inflammation in cancer patients, the clinical utility of such a biomarker in healthy individuals remained uncertain. If deviations in blood cell counts were persistent over years or decades, these alterations could have an impact on immune regulation and immunosenscence, both likely contributors to chronic disease risk. Since we do not fully understand the underlying mechanisms, it is plausible that perturbations in genomic stability and cell cycle pathways could be altered as well. The strongest effect of mLOY is seen in the myeloid lineage, which is consistent with the immune hypothesis as a key element. The involvement of the myeloid lineage also suggests CHIP (a correlated phenotype) may have some relevance for these observed associations. We observed no relationship with basophil and eosinophil counts as well as overall lymphocyte counts.

It is notable that mLOY is associated with other non-leukocyte parameters, such as an increase in erythrocyte size and a decrease in hemoglobin concentration per cell as well as an increase in thrombocyte counts accompanies by a decrease in platelet distribution width. The changes in erythrocyte indices were similar to macrocytic hypochromic anemia. And the most common causes for macrocytic anemia were vitamin B12 and folate deficiency70. A report in 2016 on National Diet and Nutrition Surveys found that 12.4% and 6.4% women in childbearing age were deficient in serum vitamin B12 and folate despite 96% consumption of adequate B12 in UK71 suggesting that the current recommended intake of vitamin B12 and folate might require adjustment to accommodate difference in life style or genetic background which may influence bioavailability. The intake and deficiency of vitamin B12 and folate among men was under-studied. The cross-sectional design of current investigation is inadequate for elucidating causal relationship, but the potential involvement of mLOY and vitamin B12 and folate metabolism might warrant further study. The effect of mLOY on red blood cells is intriguing in light of the steady decline in hematopoietic regeneration after middle age- and indeed, our finding could be correlated but not causally related to such72.

Despite careful consideration of the effects of age and tobacco use in our analysis, we cannot rule out potential biases of residual confounding, or confounding by other unmeasured or unadjusted exposures. Increasing age and tobacco use are associated with both mLOY and changes in blood cell count indices and warrant careful consideration to remove potential confounding in our analysis of the association between mLOY and blood cell counts. To adjust for these effects, multivariable regression models adjusted for a 25-level smoking variable and allowed for non-linear relationships with age. Furthermore, stratified analyses restricted to strata of age group and smoking status found no major differences in overall analytical outcome except for in sub-analyses of lymphocytes; suggesting potential effect modification by age and tobacco use for lymphocytes. Additionally, we used a mLOY PRS as a genetic instrumental variable to further investigate the association between mLOY and blood cell counts. Again, blood cell indices that were significantly associated with mLOY in the observational data were also associated in this genetic analysis. The only exception was erythrocyte indices which remained highly significant but had effect sizes in the opposite direction, suggesting environmental contributors may have strong influence in this relationship.

Our analysis in the UK Biobank provides important evidence that mLOY in circulating blood cells is associated with changes in blood cell counts. Our cross-sectional investigation is unable to determine the temporality of this relationship (e.g., does mLOY precede changes in blood cell count). Results from our mediation analyses indicate mLOY could account for a small proportion of age and smoking-related effects on blood cell count; suggesting mLOY may precede changes in blood cell counts. Alternatively, the PRS analysis in women (who do not carry a Y chromosome) demonstrates a strong relationship between mLOY genetic susceptibility variants and blood cell counts independent of chromosome Y loss, suggesting blood cell count and mLOY may share common genetic risk factors related to genomic instability and cell cycle regulation or alternatively that genetic susceptibility to mLOY in men may be associated with genetic susceptibility to chromosomal alterations in women (e.g., mosaic chromosome X loss) that may have similar impacts on blood cell counts. Regardless, our analysis suggests mLOY and blood cell counts are highly associated and are relevant for underlying disease risk. Although the specific mechanisms responsible for the association between mLOY and blood cell counts are unclear, our work highlights the need to explore the functional bases of the reported associations. Future studies that examine the molecular impact of mLOY on cellular transcription, cell cycle regulation and differentiation are vital for expanding our understanding of how mLOY could have an impact on hematopoiesis, particularly in the aging population, and could provide novel insights into potential biological mechanisms responsible for the observed associations between mLOY and possible cancer and chronic disease risk.

Transparency statement

The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as originally planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Patient and public involvement

The development of the research question or outcome measures was not informed by patients’ priorities, experience, or preferences. No patients were involved in the design and conduct of the present study. There are no plans to disseminate the results to study participants.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Blanche P. Alter for her critical input on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute. This research was conducted using the UK Biobank resource (application 21552). The UK Biobank was established by the Wellcome Trust, the Medical Research Council, the United Kingdom Department of Health, and the Scottish Government. The UK Biobank has also received funding from the Welsh Assembly Government, the British Heart Foundation, and Diabetes UK.

Author contributions

M.J.M. conceived and designed the study. E.L., N.D.F., S.J.C., M.J.M., M.Y. and W.Z. contributed to the acquisition and management of data. S.L., J.S. and M.J.M. contributed to the analysis of data. S.L., S.J.C. and M.J.M. drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, critically revised the manuscript and approved the final text.

Data availability

The data reported in this paper are available by application directly to the UK Biobank. The associations between mLOY and outcomes are provided in the supplementary data. Software code in R for the analyses is available upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-59963-8.

References

- 1.Machiela MJ, Chanock SJ. Detectable clonal mosaicism in the human genome. Semin. Hematol. 2013;50:348–359. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steensma DP, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2015;126:9–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-631747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forsberg LA, et al. Mosaic loss of chromosome Y in peripheral blood is associated with shorter survival and higher risk of cancer. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:624–628. doi: 10.1038/ng.2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou W, et al. Mosaic loss of chromosome Y is associated with common variation near TCL1A. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:563–568. doi: 10.1038/ng.3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loftfield E, et al. Mosaic Y Loss Is Moderately Associated with Solid Tumor Risk. Cancer Res. 2019;79:461–466. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zink F, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis, with and without candidate driver mutations, is common in the elderly. Blood. 2017;130:742–752. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-02-769869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumanski JP, et al. Mutagenesis. Smoking is associated with mosaic loss of chromosome Y. Science. 2015;347:81–83. doi: 10.1126/science.1262092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong JYY, et al. Outdoor air pollution and mosaic loss of chromosome Y in older men from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Environ. Int. 2018;116:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumanski JP, et al. Mosaic Loss of Chromosome Y in Blood Is Associated with Alzheimer Disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;98:1208–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haitjema S, et al. Loss of Y Chromosome in Blood Is Associated With Major Cardiovascular Events During Follow-Up in Men After Carotid Endarterectomy. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2017;10:e001544. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumanski JP, Sundström J, Forsberg LA. Loss of Chromosome Y in Leukocytes and Major Cardiovascular Events. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2017;10:e001820. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.117.001820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright DJ, et al. Genetic variants associated with mosaic Y chromosome loss highlight cell cycle genes and overlap with cancer susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:674–679. doi: 10.1038/ng.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loftfield E, et al. Predictors of mosaic chromosome Y loss and associations with mortality in the UK Biobank. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:12316. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson Deborah J., Genovese Giulio, Halvardson Jonatan, Ulirsch Jacob C., Wright Daniel J., Terao Chikashi, Davidsson Olafur B., Day Felix R., Sulem Patrick, Jiang Yunxuan, Danielsson Marcus, Davies Hanna, Dennis Joe, Dunlop Malcolm G., Easton Douglas F., Fisher Victoria A., Zink Florian, Houlston Richard S., Ingelsson Martin, Kar Siddhartha, Kerrison Nicola D., Kinnersley Ben, Kristjansson Ragnar P., Law Philip J., Li Rong, Loveday Chey, Mattisson Jonas, McCarroll Steven A., Murakami Yoshinori, Murray Anna, Olszewski Pawel, Rychlicka-Buniowska Edyta, Scott Robert A., Thorsteinsdottir Unnur, Tomlinson Ian, Moghadam Behrooz Torabi, Turnbull Clare, Wareham Nicholas J., Gudbjartsson Daniel F., Kamatani Yoichiro, Hoffmann Eva R., Jackson Steve P., Stefansson Kari, Auton Adam, Ong Ken K., Machiela Mitchell J., Loh Po-Ru, Dumanski Jan P., Chanock Stephen J., Forsberg Lars A., Perry John R. B. Genetic predisposition to mosaic Y chromosome loss in blood. Nature. 2019;575(7784):652–657. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1765-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sudlow C, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fry A, et al. Comparison of Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics of UK Biobank Participants With Those of the General Population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017;186:1026–1034. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishizaka N, et al. Relationship between smoking, white blood cell count and metabolic syndrome in Japanese women. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2007;78:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Obesity and the white blood cell count: changes with sustained weight loss. Obes. Surg. 2006;16:251–257. doi: 10.1381/096089206776116453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakanishi N, et al. Association of alcohol consumption with white blood cell count: a study of Japanese male office workers. J. Intern. Med. 2003;253:367–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Twig G, et al. White blood cells count and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young men. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:276–282. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karthikeyan VJ, Lip GYH. White blood cell count and hypertension. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2006;20:310–312. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai Yong Chang, Woollard Kevin J., McClelland Robyn L., Allison Matthew A., Rye Kerry-Anne, Ong Kwok Leung, Cochran Blake J. The association of plasma lipids with white blood cell counts: Results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2019;13(5):812–820. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson, D. et al. Genetic predisposition to mosaic Y chromosome loss in blood is associated with genomic instability in other tissues and susceptibility to non-haematological cancers. bioRxiv 514026, 10.1101/514026 (2019).

- 24.Tingley D, Yamamoto T, Hirose K, Keele L, Imai K. mediation: R Package for Causal Mediation Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2014;59:1–38. doi: 10.18637/jss.v059.i05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamat MA, et al. PhenoScanner V2: an expanded tool for searching human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2019;35:4851–4853. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staley JR, et al. PhenoScanner: a database of human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2016;32:3207–3209. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crosslin DR, et al. Genetic variants associated with the white blood cell count in 13,923 subjects in the eMERGE Network. Hum. Genet. 2012;131:639–652. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1103-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiner AP, et al. Genome-wide association study of white blood cell count in 16,388 African Americans: the continental origins and genetic epidemiology network (COGENT) PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soranzo N, et al. A genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 22 loci associated with eight hematological parameters in the HaemGen consortium. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1182–1190. doi: 10.1038/ng.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okada Y, et al. Common variations in PSMD3-CSF3 and PLCB4 are associated with neutrophil count. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:2079–2085. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferreira MAR, et al. Sequence variants in three loci influence monocyte counts and erythrocyte volume. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;85:745–749. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lo KS, et al. Genetic association analysis highlights new loci that modulate hematological trait variation in Caucasians and African Americans. Hum. Genet. 2011;129:307–317. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0925-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, et al. GWAS of blood cell traits identifies novel associated loci and epistatic interactions in Caucasian and African-American children. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22:1457–1464. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamatani Y, et al. Genome-wide association study of hematological and biochemical traits in a Japanese population. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:210–215. doi: 10.1038/ng.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gudbjartsson DF, et al. Sequence variants affecting eosinophil numbers associate with asthma and myocardial infarction. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:342–347. doi: 10.1038/ng.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Astle WJ, et al. The Allelic Landscape of Human Blood Cell Trait Variation and Links to Common Complex Disease. Cell. 2016;167:1415–1429.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keller MF, et al. Trans-ethnic meta-analysis of white blood cell phenotypes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:6944–6960. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jain D, et al. Genome-wide association of white blood cell counts in Hispanic/Latino Americans: the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017;26:1193–1204. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Southam L, et al. Whole genome sequencing and imputation in isolated populations identify genetic associations with medically-relevant complex traits. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15606. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Q, Kathiresan S, Lin J-P, Tofler GH, O’Donnell CJ. Genome-wide association and linkage analyses of hemostatic factors and hematological phenotypes in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med. Genet. 2007;8(Suppl 1):S12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kullo, I. J., Ding, K., Jouni, H., Smith, C. Y. & Chute, C. G. A genome-wide association study of red blood cell traits using the electronic medical record. PloS One5 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Ganesh SK, et al. Multiple loci influence erythrocyte phenotypes in the CHARGE Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1191–1198. doi: 10.1038/ng.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Harst P, et al. Seventy-five genetic loci influencing the human red blood cell. Nature. 2012;492:369–375. doi: 10.1038/nature11677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gieger C, et al. New gene functions in megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation. Nature. 2011;480:201–208. doi: 10.1038/nature10659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ding K, et al. Genetic Loci implicated in erythroid differentiation and cell cycle regulation are associated with red blood cell traits. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2012;87:461–474. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uda M, et al. Genome-wide association study shows BCL11A associated with persistent fetal hemoglobin and amelioration of the phenotype of beta-thalassemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:1620–1625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711566105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Rooij FJA, et al. Genome-wide Trans-ethnic Meta-analysis Identifies Seven Genetic Loci Influencing Erythrocyte Traits and a Role for RBPMS in Erythropoiesis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;100:51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hodonsky CJ, et al. Genome-wide association study of red blood cell traits in Hispanics/Latinos: The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meisinger C, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies three loci associated with mean platelet volume. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;84:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qayyum R, et al. A meta-analysis and genome-wide association study of platelet count and mean platelet volume in african americans. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soranzo N, et al. A novel variant on chromosome 7q22.3 associated with mean platelet volume, counts, and function. Blood. 2009;113:3831–3837. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramsuran V, et al. Duffy-null-associated low neutrophil counts influence HIV-1 susceptibility in high-risk South African black women. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2011;52:1248–1256. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guerrero JA, et al. Novel loci involved in platelet function and platelet count identified by a genome-wide study performed in children. Haematologica. 2011;96:1335–1343. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.042077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schick UM, et al. Genome-wide Association Study of Platelet Count Identifies Ancestry-Specific Loci in Hispanic/Latino Americans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;98:229–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin BD, et al. 2SNP heritability and effects of genetic variants for neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;62:979–988. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2017.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Staley, O. Y. J. MendelianRandomization: Mendelian Randomization Package (2019).

- 57.Wickham, H. ggplot2:Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. (Springer, 2016).

- 58.Lüdecke, D., Bartel, A., Schwemmer, C. & Powell, C. sjPlot: Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Science (2019).

- 59.Zhu Ying, Wei Yongyue, Zhang Ruyang, Dong Xuesi, Shen Sipeng, Zhao Yang, Bai Jianling, Albanes Demetrius, Caporaso Neil E., Landi Maria Teresa, Zhu Bin, Chanock Stephen J., Gu Fangyi, Lam Stephen, Tsao Ming-Sound, Shepherd Frances A., Tardon Adonina, Fernández-Somoano Ana, Fernandez-Tardon Guillermo, Chen Chu, Barnett Matthew J., Doherty Jennifer, Bojesen Stig E., Johansson Mattias, Brennan Paul, McKay James D., Carreras-Torres Robert, Muley Thomas, Risch Angela, Wichmann Heunz-Erich, Bickeboeller Heike, Rosenberger Albert, Rennert Gad, Saliba Walid, Arnold Susanne M., Field John K., Davies Michael P.A., Marcus Michael W., Wu Xifeng, Ye Yuanqing, Le Marchand Loic, Wilkens Lynne R., Melander Olle, Manjer Jonas, Brunnström Hans, Hung Rayjean J., Liu Geoffrey, Brhane Yonathan, Kachuri Linda, Andrew Angeline S., Duell Eric J., Kiemeney Lambertus A., van der Heijden Erik HFM, Haugen Aage, Zienolddiny Shanbeh, Skaug Vidar, Grankvist Kjell, Johansson Mikael, Woll Penella J., Cox Angela, Taylor Fiona, Teare Dawn M., Lazarus Philip, Schabath Matthew B., Aldrich Melinda C., Houlston Richard S., McLaughlin John, Stevens Victoria L., Shen Hongbing, Hu Zhibin, Dai Juncheng, Amos Christopher I., Han Younghun, Zhu Dakai, Goodman Gary E., Chen Feng, Christiani David C. Elevated Platelet Count Appears to Be Causally Associated with Increased Risk of Lung Cancer: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2019;28(5):935–942. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roxburgh CSD, McMillan DC. Role of systemic inflammatory response in predicting survival in patients with primary operable cancer. Future Oncol. Lond. Engl. 2010;6:149–163. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dolan RD, McSorley ST, Horgan PG, Laird B, McMillan DC. The role of the systemic inflammatory response in predicting outcomes in patients with advanced inoperable cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017;116:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salman T, et al. Prognostic Value of the Pretreatment Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio for Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors: An Izmir Oncology Group Study. Chemotherapy. 2016;61:281–286. doi: 10.1159/000445045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Loh P-R, et al. Insights into clonal haematopoiesis from 8,342 mosaic chromosomal alterations. Nature. 2018;559:350–355. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0321-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Terao C, et al. GWAS of mosaic loss of chromosome Y highlights genetic effects on blood cell differentiation. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12705-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Machiela MJ, Chanock SJ. The ageing genome, clonal mosaicism and chronic disease. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2017;42:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coffelt SB, Wellenstein MD, de Visser KE. Neutrophils in cancer: neutral no more. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016;16:431–446. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fuentes E, Palomo I, Rojas A. Cross-talk between platelet and tumor microenvironment: Role of multiligand/RAGE axis in platelet activation. Blood Rev. 2016;30:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Olsson AK, Cedervall J. The pro-inflammatory role of platelets in cancer. Platelets. 2018;29:569–573. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2018.1453059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ethier J-L, Desautels D, Templeton A, Shah PS, Amir E. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. BCR. 2017;19:2. doi: 10.1186/s13058-016-0794-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nagao T, Hirokawa M. Diagnosis and treatment of macrocytic anemias in adults. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2017;18:200–204. doi: 10.1002/jgf2.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sukumar, N., Adaikalakoteswari, A., Venkataraman, H., Maheswaran, H. & Saravanan, P. Vitamin B12 status in women of childbearing age in the UK and its relationship with national nutrient intake guidelines: results from two National Diet and Nutrition Surveys. BMJ Open6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Mahlknecht U, Kaiser S. Age-related changes in peripheral blood counts in humans. Exp. Ther. Med. 2010;1:1019–1025. doi: 10.3892/etm.2010.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kratz A, Ferraro M, Sluss PM, Lewandrowski KB. Normal Reference Laboratory Values. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:1548–1563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc049016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Banfi G, et al. Reticulocyte count, mean reticulocyte volume, immature reticulocyte fraction, and mean sphered cell volume in elite athletes: reference values and comparison with the general population. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2006;44:616–622. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2006.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Budak YU, Polat M, Huysal K. The use of platelet indices, plateletcrit, mean platelet volume and platelet distribution width in emergency non-traumatic abdominal surgery: a systematic review. Biochem. Medica. 2016;26:178–193. doi: 10.11613/BM.2016.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data reported in this paper are available by application directly to the UK Biobank. The associations between mLOY and outcomes are provided in the supplementary data. Software code in R for the analyses is available upon request.