Abstract

Dental implants and transcutaneous prostheses (trans-femoral implants) improve the quality of life of millions of people because they represent the optimal treatments to edentulism and amputation, respectively. The clinical procedures adopted by surgeons to insert these implants are well established. However, there is uncertainty on the outcomes of the post-operation recovery because of the uncertainty associated with the osseointegration process, which is defined as the direct, structural and functional contact between the living bone and the fixture. To guarantee the long-term survivability of dental or trans-femoral implants doctors sometimes implement non-invasive techniques to monitor and evaluate the progress of osseointegration. This may be done by measuring the stability of the fixture or by assessing the quality of the bone-fixture interface. In addition, care providers may need to quantify the structural integrity of the bone-implant system at various moments during the patients recovery. The accuracy of such non-invasive methods reduce recovery and rehabilitation time, and may increase the survival rate of the therapies with undisputable benefits for the patients. This paper provides a comprehensive review of clinically-approved and emerging non-invasive methods to evaluate/monitor the osseointegration of dental and orthopedic implants. A discussion about advantages and limitations of each method is provided based on the outcomes of the cases presented. The review on the emerging technologies covers the developments of the last decade, while the discussion about the clinically approved systems focuses mostly on the latest (2017–2018) findings. At last, the review also provides some suggestions for future researches and developments in the area of implant monitoring.

Keywords: Dental implants, Trans-femoral implants, Osseointegration, Non-destructive evaluation methods

Introduction

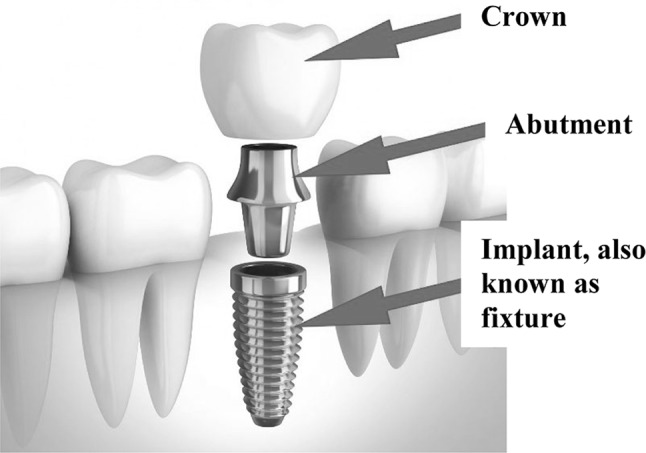

Edentulism is a significant clinical, functional, and aesthetical problem. In the U.S. about 27.3% of seniors (age 65+) and 3.75% of adults (age 20–64) have no remaining teeth [1]. Dental implant therapies are the most common solution to replace missing teeth. A dental implant (Fig. 1) is an artificial device, placed in contact with the jawbones and oral connective tissues to replace functionally and aesthetically the natural tooth. About 95% of implants are made of titanium alloy although zirconium implants are anticipated to be the fastest growing product segment in the future [2]. There are 3 million people in the U.S. who have implants, and that number is growing by 500,000 each year [3]. Owing to its aging population, Europe usually dominates the dental implant market. For example, in 2011 nearly 50% of the European population was suffering from periodontitis [2].

Fig. 1.

Example of a three parts dental implant. Figure adapted from: https://www.friscooralsurgery.com/procedures/cost-of-dental-implants/

The typical surgical procedure is based on the two-stage protocol proposed by Branemårk [4–6]. In the first stage, the implant (also known as fixture) is surgically inserted in the bone, a cover is placed, and the site is sutured. After three to 6 months, stage-two is performed: the soft tissue is opened, an abutment is connected to the implant and an artificial tooth is loaded on the abutment. In complex situations the implant supports an overdenture, framework, or bridge. In some circumstances, the time between the first and second surgery may be much longer and up to 1 year. The success of the therapy depends on the occurrence of complete osseointegration defined as the direct, structural and functional contact between living bone and implant [6], and on the ability to determine if and when full osseointegration has occurred. False negative evaluations burden the patients’ quality-of-life due to late loading; false positive evaluations lead to failures due to premature loading and carry painful and expensive consequences associated with the extraction of the failed fixture, the removal of healthy bone, and a new surgery. Some of the clinical advancements in the field of implant dentistry aim at developing single stage protocols, in which the new tooth is loaded the same day of the fixture placement [7], and at accelerating the osseointegration with the use of low-level laser pulses [8] or bioactive proteins [9], just to mention a few.

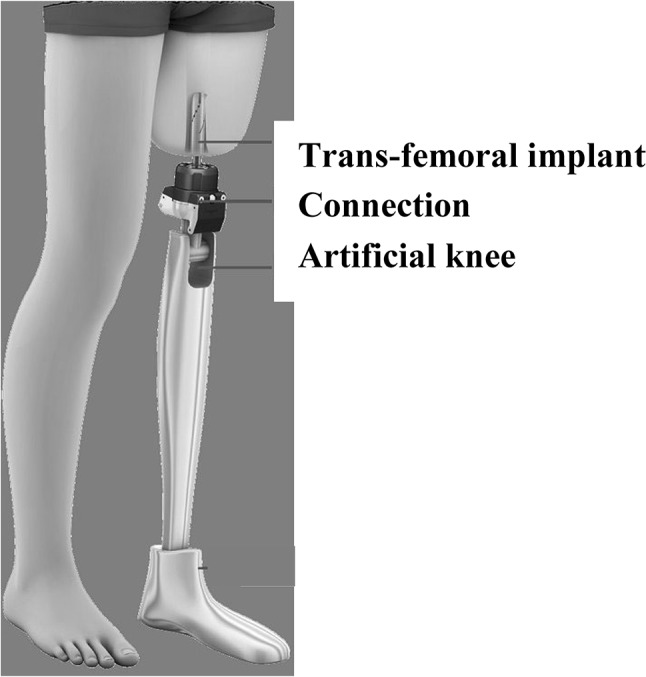

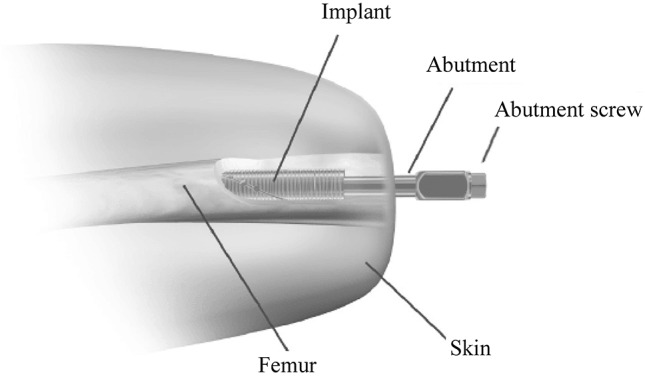

Lower limb amputation is a traumatic event that permanently alters the quality of life of amputees by affecting mobility and participation in daily activities. The leading cause of lower-limb amputation is not the same across the globe. In developed countries atherosclerosis concomitant with diabetes is the most common factor [10, 11], while in developing countries events related to industrial, traffic, and wartime injury are predominant [11, 12]. The conventional treatment for lower limb amputees is the attachment of a prosthetic limb to the body through a custom designed socket and a gel liner. The custom design maximizes comfort, better transmits the forces of the skeleton to the ground through the interposing soft tissues, and improves the movement of the residual limb to control the artificial limb [11]. However, the residual limb is a dynamic organ: it tends to atrophy over time, may swell with heat or weight gain, and often causes irritation and loss of socket fit. These cause local pain, skin ulceration and discomfort [11, 13, 14]. In addition, the fitting generally becomes more difficult for patients with a short residual limp, and for amputees with heterotopic bone formation, skin grafts, or scarring. To overcome such clinical issues, treatments based on percutaneous osseointegrated prostheses (Fig. 2) have emerged in the last two decades to bypass the need for a socket interface. In these treatments, a titanium rod-like element is attached directly to the skeleton of the residual limb. Similarly to dental implant therapies, the replacement of traditional socket prostheses with trans-femoral implants consists of a two-staged approach, except that the interval between the two stages is typically much longer and up to 18 months for the completion of reconstruction and rehabilitation from the time of the initial surgery [14]. Similar to what is being investigated for dental implantology, there is an active field of research to develop and evaluate the safety and efficacy of a single-stage osseointegration procedure [14] to reduce the recovery time to a few weeks.

Fig. 2.

Example of percutaneous osseointegrated prostheses. Figure adapted from: https://www.prostheticbody.com/percutaneous-osseointegrated-prostheses-for-amputees/

Besides dental and bone-anchored prosthetic implants, direct skeletal fixation by osseointegration is currently used in orthodontic anchor screws (miniscrews), see for example Ref. [15], total joint replacements (arthroplasty), craniofacial deficiencies, maxillofacial reconstruction, orbital prostheses, and bone-anchored hearing aids [11]. However, these therapies are not part of this review article.

Regardless of the clinical scenario, the biological process of osseointegration depends on multiple factors including bone quality and quantity, biocompatibility, and fixture design [16, 17]. For dental implants, the macro- and micro-design as well as the surface conditions of the implant have great impact on the osseointegration dynamics [16, 18], and many studies have demonstrated it [19–23]. For example, Hermann et al. [22] evaluated crestal bone changes around smooth and rough fixture surfaces in dogs. Although no significant changes were detected around implants with rough surface that were placed at the level of bone crest, implants with smooth collars showed 1.7 mm of bone loss in the first month. Another study suggested that rough implant surfaces can achieve higher and faster osseointegration when compared with machined surfaces [23].

For orthopaedic implants the rehabilitation outcomes of the direct transcutaneous prosthetic attachment rely on the longevity and strength of the bond between the fixture and bone walls and on the infection-free seal of the skin surrounding the pylon [24]. The first condition can be evaluated periodically or monitored continuously with some non-invasive methods adapted, for example, from the engineering areas of non-destructive evaluation or structural health monitoring, respectively.

This article reviews the most common methods to evaluate the osseointegration of dental implants and lower limb fixtures. Osseointegration is the common aspect concerning the two applications (dental implants and lower limb fixtures) considered in this article. The review includes emerging techniques that have not been translated yet into the clinical practice. A computer-based literature search was performed to identify those studies that were pertinent to the scope of the paper. The following databases were used beginning December 2018: PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. In PubMed, the following searches were performed: (1) “Osseointegration” AND “dental implants” AND “monitoring”; (2) “Osseointegration” AND “dental implants” AND “Osstell”; (3) “Osseointegration” AND “dental implants” AND “Periotest”; (4) “Osseointegration” AND “lower limb”. The searches in Google Scholar and Scopus were: (1) “Osseointegration” AND “lower limb” AND “RFA”; (2) “Osseointegration” AND “lower limb” AND “ultrasound”. A few manual searches were performed as well. Inclusion criteria were articles pertaining to commercial systems, studies that compare two or more systems, and methods not yet approved by regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Primary exclusion criteria were articles entirely related to health-related quality-of-life outcomes, infections, clinical complications, animal models only, and microbiological or histological evaluations. Secondary exclusion criteria were study protocols, studies based on finite element analysis only, short communications, single-case studies, conference abstracts, and articles in languages other than English. The outcome of this search is the literature [25–146] reviewed and elaborated in this article.

One of the main scopes of the paper is help newcomers in the area of evaluation and monitoring of medical implants at navigating the several hundreds of studies in the subject some of which provide conflicting statements about advantages and limitations of the methods. Another aim of the paper is to cross-pollinate ideas to and from the engineering disciplines of non-destructive evaluation and structural health monitoring in order to provide innovative or advanced solutions to clinical challenges that are of interest for millions of people worldwide. The review also helps biomedical experts and bioengineers by providing an overview of the latest advancements in two separate but similar clinical applications: dental implants and trans-femoral prostheses.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the methodologies relative to dental implants and is subdivided in four sub-sections: clinical problem; commercial systems; comparative studies; and emerging technologies. Section 3 reviews the techniques relative to limb reconstruction and is divided in two subsections: clinical challenges and monitoring strategies. Section 4 ends the article with some concluding remarks and a few suggestions for future academic researches in the area of non-invasive evaluation/prognostics of osseointegration process.

Dental implants

Clinical Problem

A dental implant is an artificial titanium alloy or zirconia device that serves to replace the natural tooth. Implant stability is a necessary requirement for the osseointegration and it can be considered a two-stage process that depends on the bone healing time [25, 26]. The primary stability is achieved immediately after the surgical procedure as the outcome of the mechanical interlock between the fixture and the bone. It depends upon factors such as bone quality and quantity, type of implant, placement technique used, and compressive stresses at the implant tissue interface. The primary stability is fundamental for the success of osseointegration [27], and several studies showed that poor stability is one of the major causes of therapy failure [28, 29] whereas implants with adequate primary stability require shorter healing periods [27]. The secondary stability is instead attained by biological bone formation and remodeling at the implant/bone interface [26], and may require several weeks or a few months in order to be fully attained, at the end of which the superstructure is loaded.

In the two-stage surgical protocol doctors and patients decide when to load the superstructure. The decision involves a few clinical parameters among which the stability of the implant is the most important. Typically, the degree of stability is difficult to judge objectively and the “tactile feeling”, although it is still widely used by clinicians, is not a reliable baseline for future comparisons. Whenever deemed appropriate, clinicians may consider also immediate loading.

Besides stability, the success of dental implants depends on the placement site, patient’s conditions, surgeon’s experience, and surgical technique. Failures may occur prior to occlusal loading with a prosthetic superstructure or later after loading [30]. Based on chronological criteria, the biological failures can be classified into early and late failures. The former is due to unsuccessful osseointegration, indicating impaired bone healing. Smoking, implant design, infection, and insufficient bone quality/quantity may also trigger early failures [30–32]. Late failures are instead due to loss of osseointegration [30, 33].

The correct diagnosis and timeline of the healing process is pivotal to guarantee the success of the therapy. Premature load of the crown may lead to failure which requires the extraction of the implant, the consequent removal of healthy bone, and a new surgery. Late loading adds cosmetic and quality-of-life burden to the patient. Once the artificial teeth are connected, the implants are subjected to repetitive functional chewing forces that they must be able to resist and not experience inflammation or bone loss.

Pjetursson and Heimisdottir [34] summarized some statistics about the survival rates of dental implants. In the early ‘90s the 5-years survival rate of implants supporting overdentures was 92% while those supporting fixed reconstructions was 95% [35]. Recent data show that every year about 2–3% of inserted implants are lost during the healing phase, while 0.3–1.3% of implants are lost after loading [34]. Owing to the number of implants placed every year, even a small percentage still implies that thousands of procedures fail each year. Statistics originally published in [36, 37] and then summarized in [34] show that the 10-year survival rate for implant supporting single crowns is 95.2%, for implants supporting fixed dental prostheses is 93.1%, and for implants supporting combined tooth—implant-supported prostheses is 82.1%. Some scientists may argue that the actual success rate is overestimated because the interest at reporting such failures is low.

Monitoring strategies: consolidated commercial systems

The methods to determine the stability of dental implants and to quantify/evaluate the stiffness of the osseous tissue-implant interface can be clustered in two groups: invasive and non-invasive. The latter, in turn, can be divided in three subgroups [38–40]: palpation, imaging, and biomechanics. The biomechanical methods are the main topics of this review article.

The most popular invasive (destructive) approach is the histological analysis, called histomorphometry. This is considered the gold standard for the assessment of osseointegration [41]. Histological-based methods rely on the quantitative study of the peri-implant bone quantity and bone-implant contact from a dyed specimen. The conventional protocol consists of embedding the samples in Methacrylate-based resin, cutting them in 100 μm thick slices and staining them. The analysis enables to identify important microscopic features that cannot be obtained otherwise. The procedure is invasive because it requires a biopsy, and therefore cannot be applied in vivo.

Other invasive methods include tensional test, pull-out test [42], and reverse torque. The first two have no practical applications in vivo and their use is limited to non-clinical or experimental studies. The torque-based method is consider by many as non-invasive and will be discussed in Sect. 3.2. It is anticipated here that this method may cause the physical rotation of the implant within the jawbone, may disrupt any healing that has taken place, can damage the bone-implant interface, or may further weaken if not dislodge an “ailing implant”.

Palpation and patient sensation is the empirical non-invasive approach used by dentists to determine when to load the implant with the prosthesis [38]. However, the method is prone to human errors and lack of precision.

Imaging methods based on radiography and computed tomography (CT) cluster a group of different techniques including periapical radiography, panoramic radiography, occlusal radiography, cephalometric radiography, conventional tomographic radiography, CT, medical CT, cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), and magnetic resonance imaging [43]. They can be utilized prior and after the surgery. Prior to surgery, they are used to estimate the geometry of the bones, the cortical bone thickness, the density of mineralization, and the amount of cancellous bone. The images serve to estimate changes in bone quantity and quality, and can determine any crestal bone loss. Radiography is the major method used clinically because of its convenience and because it can be performed at any stage [42]. Conventional radiography has a poor capacity to predict < 30–40% in the changes of bone minerals [44] as well as trabecular bone loss, provides two dimensional questionable image resolution; moreover, standardized X-rays are difficult to achieve, making quantitative measurements challenging [42]. In addition, standard radiographic methods produce a planar image, i.e. produce a two-dimensional projection, which means that the information given by these images is actually a ‘sum’ (or integral) of tissue density in the projection direction [43]. Other uncertainties of these 2D imaging techniques are associated with film placement errors (periapical and occlusal techniques), patient positioning errors (panoramic radiography), and influence of the operator skills [43].

To overcome such limitations, 3-D CT is preferred because produces tomographic sections able to differentiate and quantify hard and soft tissues. However, bulkiness, cost, scatter-effects from the metallic fixture, and concerns about the patient’s exposure to radiation prevent the widespread use of CT equipment.

In a laboratory research setting, osseointegration can also be effectively assessed by microcomputed tomography, as described for instance by Sasaki et al. [45] who tested the effects of a dental implant in a rabbit tibia, which is an accepted approach to study dental implant-bone interaction [46–48]. CBCT is better than CT because requires less radiation exposure for the patient [43].

Common issues for both 2D and 3D imaging techniques are the lack of calibration, i.e. the lack of a reference phantom against which the absolute bone density can be measured, and the diffraction (noise) caused by the metal parts in the immediate proximity of the implant [43].

Biomechanical methods are preferred over imaging methods because they are portable, cost-effective, and harm-free. The percussion test is an empirical approach and perhaps the simplest biomechanical test to estimate the level of osseointegration. It is similar to the coin-tap test used in nondestructive evaluation [49]. The clinical assessment is based on the sound heard upon percussion with a metallic instrument. A clearly ringing “crystal” sound indicates successful osseointegration, whereas a “dull” sound may indicate poor or complete lack of osseointegration. As the method relies on the careprovider’s experience and skills, its standardization is difficult [50].

The most important biomechanical-based approaches are the torque resistant, the Periotest® system commercialized by Siemens AG (Germany), and the resonant frequency analysis (RFA), commercialized by Osstell AB and Integration Diagnostics, Ltd. both from Sweden.

The torque resistant test, also known as the reverse-torque test, consists of reversing or unscrewing the implant with a torsional force at the time of abutment connection. The technique essentially measures the ability of the fixture to withstand a given torque value. Fixtures that rotate under the applied torque are considered failures and are removed. During the test, the osseointegrating surface may fracture under the applied torque stress. As such, this technique can be considered, to some extent, invasive. A more conservative approach consists of establishing a torque threshold preventively and assess whether the implant can withstand it without failure. The outcome of the measurement is a “pass or fail” information. Typical torque values are 20 N cm [38] or higher [51]. Regardless of the value, the implant is expected to not rotate. As experiments on animals demonstrated that re-integration of loosened and rotationally mobile implants is possible, this technique has fallen into disrepute [38, 52].

The reverse torque is the inverse of the insertion torque (IT) technique. In the latter, customized or commercial manual or electronic hand wrenches are used to insert the implants and to measure the peak insertion torque, i.e. the peak resistance to the torsional force necessary to insert the fixture. Greenstein and Cavallaro [53] conducted a literature review to determine the role of insertion torque in attaining primary stability in healed ridges and fresh extraction sockets. The authors found that torque above 30 N cm is routinely used to place implants into healed ridges and fresh extraction sockets prior to immediate loading of implants. Higher torque above 50 N cm is desirable to reduce micromotion and it does not appear to damage bone. The authors also found that healing seems to be unaffected whether 30+ or 50+ N cm were used to place the implant.

In Periotest® an electronically controlled rod taps an implant 4 times/s for 4 s. The rod is decelerated when it touches the implant and the duration of the contact with the fixture is measured by an accelerometer located inside the tapper. The greater the stability, the higher is the deceleration. The duration is electronically converted into the Periotest value (PTV), which according to the manufacturer, is expected to range between − 8 and + 50. Loose implants cause a longer contact time and the PTVs are correspondingly higher, while osseointegrated implants have a short contact time which results in negative PTVs [39, 54–56]. Despite decades of research and development, the reliability of the Periotest has been questioned as the PTV seems to be related to many parameters including position of the instrument [57], angle and distance with respect to the implant [42, 58], and abutment length [26]. For example, the distance between the rod and the test surface should be 0.6–2.0 mm distance and if the distance is over 5 mm, the measured value may be insignificant [59]. The most failing point of Periotest® is that the percussing force may compromise the healing of initially-poor stable implants [40, 42]. In addition, some critics believe that the Periotest® is not highly reproducible because it is difficult to carry out at the same location and with the same angle. The latest advancement in this technology is Periotest M, a hand-held mobile device that performs wireless osseointegration measurements. The wireless design allows the user more freedom of movement.

Owing to its ability of assessing the stability of implants, the Periotest® system is sometimes used to validate new surgical procedures. For example, Mahest et al. [60] used the PTV to compare the stability of implants placed in sockets augmented with calcium phospho-silicate putty to implants placed in naturally healed sockets. Twenty-two single extraction sockets were implanted with putty immediately after extraction and the implants were inserted after 5–6 months of healing. Meantime twenty-six implants were placed in 22 patients, with naturally healed sockets. The PTVs showed a significant difference between the two groups: the PTVs in the grafted group were lower than the naturally healed group, indicating better implant stability in sites grafted with putty. Within the limits of this study, the outcome of this work suggests that socket grafting with calcium phospho-silicate putty putty may enhance the quality of available bone for implantation.

Implatest and the Implomates [43] are devices similar to the Periotest. The former differs from the Periotest because the accelerometer used to acquire the implant vibrations is supported by a flexible membrane connected to the probe’s body, in order to isolate the accelerometer from the probe’s motion. The Implomates instead generates the impact with a metallic rod driven by an electromagnetic field, and the vibration is acquired by a microphone, and subsequently analyzed in the frequency domain, in a range between 2 and 20 kHz [50, 61].

The first commercial system based on the RFA [39, 62, 63] consisted of a small L-shaped transducer screwed to an abutment in order to excite a sinusoidal vibration in the 5–15 kHz range. The engineering principle behind this method is that when the implant stability increases, i.e. when the stiffness of the bone-implant interface increases, the vibration frequencies increase. In the RFA, the frequency of the first resonance peak is measured and converted into the implant stability quotient (ISQ), which ranges from 0 to 100: the higher the ISQ, the more stable the implant. ISQ 1 correspond approximately to 1 kHz whereas ISQ 100 correspond approximately to 10 kHz [64]. The system was commercialized by Osstell and it is now at its third generation with the Osstell® being the first generation, the Osstell® Mentor the second generation, and the Osstell® ISQ the third generation. In the latter, a sensor—known as the SmartPeg—is attached to the implant and is gently vibrated for a short time by magnetic pulses. To avoid damage to the implant, part of the SmartPeg is made of a quite soft material, which limits the lifetime of its threads. The company website lists over 900 scientific articles related to Osstell and ISQ [65], spanning from the oldest seminal paper of Meredith et al. [25] to the newest one [66].

Practitioners consider values ISQ < 45–50 risky for adequate stability [63] but higher ISQs values at the time of placement do not guarantee future 100% success of immediately and early loaded dental implants [42]. Some clinical studies collected the RFA of immediately loaded dental implants: 11–28.6% of those with high ISQ values failed [67–71]. Other studies conducted on animals demonstrated poor correlation between RFA and histomorphometric parameters such as bone volume density and bone-implant contact [52, 72, 73]. Some researchers [67] concluded that RFA can assess the healing status in the cortical bone area, but it provides little information about the healing status of trabecular bone at the fixture/bone interface. As, it is still not clear how osseointegration can be noninvasively quantified, several authors suggested that RFA should be used in combination with other methods for determining stability [40, 67, 70, 74].

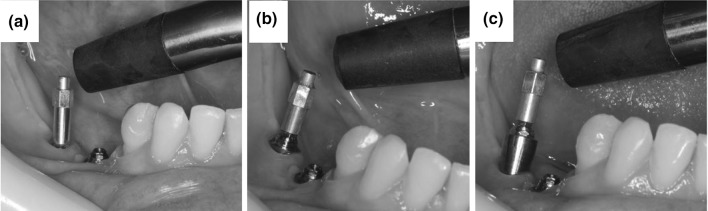

Owing to the engineering principles behind the RFA, the ISQ depends on the abutment height, as demonstrated in [75], where twelve patients and 31 dental implants, 4.1 × 10 mm (Fig. 3), were observed. Three Smartpegs were inserted one at a time, and the ISQs were taken on mesial, distal, buccal, and lingual surfaces. The results showed that the mean ISQ ranged from 88.27 ± 5.70 to 66.33 ± 3.67 [75]. The effect of the fixture lengths on the ISQ was also investigated by Bataineh and Al-dakes [76] who used an Osstell Mentor to measure 135 implants inserted in 22 ribs of the same cow. Each rib end received a group of three implant lengths, namely 8, 13, and 15 mm having a diameter equal to 3.8 mm. The statistical analysis showed that the ISQ is dependent on the fixture length (the longer, the higher). The authors concluded that increasing dental implant length plays a fundamental role in increasing its primary stability, even in poor bone quality, through controlling the bone preparation process. The authors also reported the difficulty to keep the probe perpendicular to the transducer and discussed about the influence of the position on the horizontal plane on the ISQ. For the study, Bataineh and Al-dakes [76] chose the higher ISQ obtained in each test, each of them carried out at 90° of separation between them and another one on the horizontal plane. Another study investigated the effects of the implant angulation on the resonance frequency [147].

Fig. 3.

Example of a resonance frequency analysis performed on the same implant with an Osstell device. a Implant platform, b 1 mm microunit, and c 5 mm microunit. Figure adapted from 10.1371/journal.pone.0181873.g001

With the quest for reducing the overall surgical procedures related to dental prosthetics, an open debate is about the validity of immediate implant placement into fresh extraction sockets. Rowan et al. [77] collected the ISQ data obtained with an Osstell system to compare the stability of immediately placed implants to the stability of implants placed at healed sites. The data were collected from 137 Nobel Replace Tapered Groovy Implants placed in 85 patients 19–93 years old by the same surgeon. Forty-one fixtures were placed immediately after extraction with MasterGraft bone grafting material whereas the remaining were inserted in healed sites with no grafting material. The ISQs were recorded at the time of placement and at a subsequent follow-up appointment; the latter was split into 2- to 3-month and 4- to 6-month groups. The data were analyzed using simple linear regression. At the moment of placement, the ISQ relative to healed sites had higher average values than the other group. In the months after the surgical procedure, both groups exceeded the ISQ threshold of 65 although the implants placed in the healed sites had consistently higher ISQ. The authors concluded that, although mean ISQ values of immediately placed implants are lower than those of delayed implants, the early implants still can be considered successful because the ISQ results 65 or higher [77]. Similar conclusions were obtained by another group [78].

Some authors used the RFA to prove the validity of new dental implant therapies [8, 9]. Torkzaban et al. [8] used the Osstell Mentor system to evaluate the benefit of low-level laser therapy in promoting osteoblastic activity and tissue healing. The clinical trial was performed on 80 implants from 19 patients. Implants were randomly divided into two groups one of which was subjected to seven sessions of laser therapy. The Mentor device was used immediately after surgery and 10 days and 3, 6, and 12 weeks later. Statistical test revealed no significant difference in the mean values of ISQ and therefore implant stability between the test and control groups over time. The authors concluded that the laser therapy had no significant effect on the stability. Pirpir et al. [9] used an Osstell device to evaluate the advantages of growth factors in improving the stability of dental implants. Growth factors are bioactive proteins that control the wound healing process. Twelve patients (5 males, 7 females), age 20–68 years old were included. A total of 40 implants were placed. Half of them were included in the study group which contained concentrated growth factor; the other 20 were included in the control group. The distribution of gender, installed implant diameter, and bone quality between the control group and the experimental group did not show any statistically significant difference. No significant difference was also observed between the two groups in terms of average insertion torque at the moment of the implant placement. The mean ISQs after the placement were 75.75 ± 5.552 for the control group and 78.00 ± 2.828 for the study group, and there was no statistically significant difference either between the two groups. The RFA was then applied again 1 week and 4 weeks after the surgery. The mean ISQs were found to be 79.40 ± 2.604 for the study group and 73.50 ± 5.226 for the control (at week 1), and 78.60 ± 3.136 for the study group and 73.45 ± 5.680 (at week 4). As the differences between the groups were found to be statistically significant, it was concluded that the concentrated growth factor improve the stabilization.

The Osstell devices are currently considered by many the clinical standard for determining the appropriate time for functional loading and longitudinal monitoring of the changes of dental implant stability [67–69]. However, in a 2014 review, Mathieu et al. [41] who have been actively working on a new method called quantitative ultrasounds (see Sect. 2.4), wrote that the “fundamental flaw” of the RFA-based systems is that they consider the first resonance frequency only, framed into the ISQ. This quotient is intuitively easy for the clinician but has limited value from a structural mechanics point of view. The ISQ is therefore perceived as an “oversimplification” of the dynamic response of the bone–implant system [41].

Integration Diagnostics Ltd. introduced a new kind of RFA-based device: the Penguin RFA [79]. It has a small pen-like design (Fig. 4) and a multiuse transducer (MulTiPeg). Buyukguclu et al. [80] performed a comparative study between the Osstell ISQ and the Penguin RFA. They embedded forty implants in self curing acrylic resin, soft-lining material, polyvinyl siloxane impression material, and polycarboxylate cement, i.e. 10 implants for each material. After complete setting, three measurements were taken with each instrument. The “intraclass correlation coefficient” evaluated the correspondence between the measurements. The results showed that both instruments gave lower ISQ in siloxane than soft-lining material, self-curing acrylic resin, and cement. The authors concluded that Penguin RFA and Osstell ISQ are reliable only when the implants are embedded in stiff materials with the latter more reliable than the Penguin RFA [80].

Fig. 4.

The Penguin RFA. The figure on the left is from https://www.pinterest.com/pin/560276009885439730/. The figure on the right is from https://aseptico.com/store/implant-surgery/implant-systems/penguin-rfa/

Note that in [80] Osstell and Integration Diagnostics appear to be the same commercial entity. As a matter of fact, in 2016 Osstell filed a patent infringement lawsuit against Integration Diagnostics [81]. Two years later (March 2018), the Patent and Market Court in Stockholm sided with Integration Diagnostics and found non-infringement [82].

Comparative studies

One of the active fields of research in implant dentistry aims at finding a correlation in the measurements of at least two of the three commercial methods described above. The premise is that correlation and reliability, for instance between ISQs and PTVs, are a controversial issue [83]. As a matter of fact, some studies showed a strong correlation between the two methods [84] whereas others suggested that there is no correlation at all [68]. Oh et al. [84] compared the Periotest and the Osstell systems and did not find any significant difference between the PTV and ISQ, which both correlated well with the bone formation rate. However, Alonso et al. [85] found only a “moderate correlation” between PTV and ISQ. Another attempt to compare PTV and ISQ was conducted by Oh et al. [86] who used five evaluators with different training and clinical experience. Two endosseous implants were placed in each of a soft Balsa and a hard Euro-Beech wood block. The PTV and ISQ of each implant were measured nine times by each evaluator. The repeatability of the measurements were quantified statistically using a paired t test, 1-way ANOVA, and post hoc Tukey multiple comparison test. Within the limits of the study, the results showed that at any given wood block the means of the PTVs were similar regardless of the implants and with little difference among the evaluators. For the ISQ instead, at any given wood block the means of the values were different for different implant and with some discrepancy among the evaluators [86].

To answer the questions about any correlation among PTV, ISQ, and insertion torque (IT), a few systematic review papers analyzed any relationship between PTV and ISQ [87], and between ISQ and IT [75]. Andreotti et al. [87] carefully reviewed and tabulated six studies out of the 114 originally selected. The number of patients in these six studies ranged from 37 to 162 while the number of implants ranged from 54 to 311. Seven types of implants from five different manufacturers were used; the size spanned from 6 to 16 mm in length and from 3.25 to 6 mm in diameter. Although Andreotti and co-authors found a significant numerical correlation between ISQ and PTV, only 46% of cases coincided in relation to implant stability classification. In addition, they observed that the true PTV reported in the scientific literature ranges between − 5 and + 5.3. This range is smaller than the − 8 to + 50 range claimed by the manufacturer, and is small when compared to the ISQ range observed in the same cohort studies. Andreotti and co-authors suggested that the PTV may not always register significant differences in measurements between different groups or periods evaluated [87].

In terms of practicality, some authors [88] found the PTV-based system more user-friendly and time and cost-efficient than Osstell because unsplinted suprastructures need not be removed to evaluate the stability. However, the Periotest® measurements can be affected by a variety of factors, as discussed earlier in Sect. 2.2.

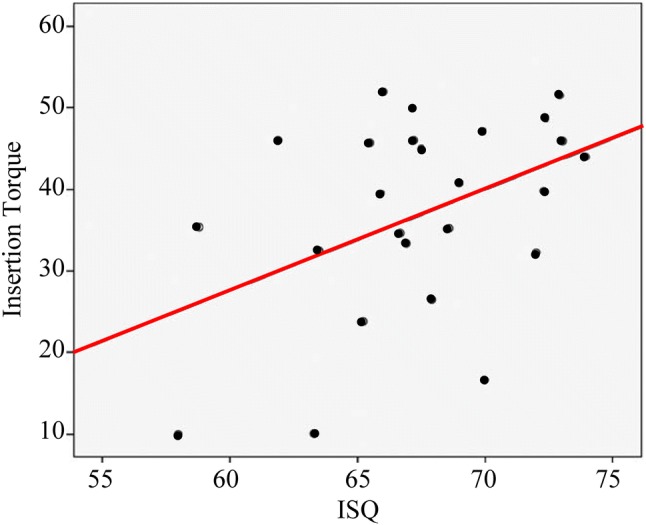

Lages et al. [75] studied a potential relationship between IT and RFA by conducting a systematic review through the most relevant scientific databases. Out of the ~ 2000 sources originally found through the scientific databases, only 12 were included in the review, after removing 770 duplicate records and 1233 exclusions after examinations of titles and abstracts. Across the twelve selected studies, the implants were placed in maxilla and mandible, in mandible, and in maxilla, and their length ranged from 9 to 16 mm and between 3 and 4.2 mm in diameter. The mean ISQ spanned from 58 ± 5.5 to 73.95 ± 3.7, whereas the minimum and maximum insertion torque were 23.2 ± 7.59 and 52.00 ± 9.23, respectively. The authors found no statistically significant correlation between ISQ and IT, as shown by Fig. 5, and concluded that IT and RFA are independent and incomparable methods of measuring primary stability [75].

Fig. 5.

Correlation between the ISQ and the insertion torque. Figure adapted from Fig. 4 of Ref. [75]

Another comparative analysis between IT and RFA was performed by Di Stefano et al. [89]. They introduced an energy-related parameter, namely the torque-depth curve integral, as a possible operator-independent reliable measure of primary stability. They compared it to known primary stability parameters, including the peak torque and the ISQ, by quantifying the integral average error and by correlating this new parameter with bone density along with other conventional parameters. Two-hundred 3.75 × 12 mm2 cylindrical commercial fixtures were inserted inside polyurethane Sawbones® foam blocks of different densities using a commercial surgical micromotor that automatically calculated the torque-depth curve integral and the peak torque during implant placement. Sawbones® is widely used to mimic the human cancellous bone. The ISQ was obtained with a SmartPeg connected to the implant at a connection torque of 5 N cm with a manual wrench; two ISQ measurements were made by pointing the probe toward the SmartPeg along two orthogonal directions. Finally, the reverse torque measurements were performed using a high-precision manual dynamometer. The implant placement was conducted by five operators to evaluate the subjectivity of the new parameter. The results proved that the torque-depth curve integral is operator independent and is correlated with the peak torque, the ISQ, and the reverse torque. The average error of these parameters was not significantly different. In addition, all the parameters considered in this study were linearly dependent on the samples’ density. However, the slope of the integral-based parameter was higher than the other, demonstrating greater sensitivity to the density variation. The main conclusion of the study was that the torque-depth curve integral provides a reliable assessment of primary stability and shows a greater sensitivity to density variations than other known primary stability parameters.

A comparison between RFA and radiographic methods was conducted by Mundim et al. [90] who found that the texture attributes obtained with computerized radiographs are significantly associated with the ISQ measured with an Osstell device. However, as pointed out by Zanetti et al. [43] no clinical validation of any of these two methods was provided.

Zanetti et al. [43] cited two works [91, 92] in which a poor correlation was found between a reverse torque test conducted up to interface failure and ISQ for both primary [91] and secondary [92] stability.

Gutierrez et al. [93] compared the IT value, obtained with a high torque ratchet wrench, to the ISQ, obtained with an Osstell Mentor®. Measurements were taken of 60 implants (31 in the maxilla and 29 in the mandible) at the time of their placement and then, 6 weeks later, a counter-torque was performed with a low torque ratchet wrench. Successful osseointegration was considered attained with a torque insertion above 35 N cm and an ISQ above 60 without mobility; the measurement was also considered “successful” when mobility was observed for torque insertion below 35 N cm and ISQ lower than 60. The opposite conditions were considered failure. The authors found no discrepancies between success and failure between the two methods and concluded that both methods tend to have the same results in relation to the studied variables. Gehrke et al. [27] compared the IT peak to the ISQ among different drill design for implant site preparation using synthetic blocks of bone of a single type density. Three different drilling sites were prepared to receive conical implants without irrigation for 10-mm in-depth. The drilled hole quality after the osteotomy was measured through a fully automated roundness/cylindricity instrument at three levels (top, middle, and bottom of the site). The results showed that the single drill group achieved a significantly insertion torque peak and ISQ than the multiple drills groups. These results suggest that the hole quality, in addition to the insertion torque, may significantly affect implant primary stability.

Monitoring strategies: academic developments

As the quest for a perfect biomechanical method is not limited to the improvements of the commercial systems described above, some authors have proposed alternative approaches. The most significant ones are quantitative ultrasounds [94–101], electromechanical impedance (EMI) [102–105], acoustic emission [106–108], and gas permeability method [109].

The quantitative ultrasonic method (QUS) uses low-intensity ultrasonic waves propagating to and from the implant to be evaluated. The hypothesis is that some features of the ultrasounds are affected by the biomechanical properties of the bone-fixture interface that acts as boundary condition. The initial study in [94] showed that when a central frequency pulse of 1 MHz is launched into a screw-shaped aluminium waveguide that is embedded in a larger aluminium block, the transmission energy depends on the contact area between the screw and the block, and the differences in the transmission that is detected are strong enough to identify varying levels of attachment. This initial study was then followed mainly by a French group [95–101] that refined a method in which a 10 MHz ultrasonic transducer is attached to the abutment screwed to the implant to be probed. A high energy pulser-receiver generates and detects short broadband ultrasonic pulses. The received signals are then analyzed in the time domain to correlate the energy of the signal to the quality of the bone-implant interface.

As part of the development, Vayron et al. [97] tested in vitro ten bovine humeri. The implants were 12 mm long and 4 mm diameter. A few years later, they compared the QUS to the ISQ values at different healing times, namely 0, 5, 7, and 15 weeks after insertion, of eighty-one identical implants inside the iliac crests of 11 sheep [100]. The ultrasonic-based technique seemed to provide a higher sensitivity to the osseointegration process, and a much lower error in the estimation of the healing time. The motivation of the improved sensitivity was attributed to the engineering biomechanics of the two methods. While the ISQ is related to the vibration of the whole bone–implant system, the short wavelength associated with the propagating ultrasounds is closely related to the bone properties confined around the implant. The same French group [101] compared the two techniques in the same implants inserted in various bone phantoms, made of polyurethane foam with different density and of cortical thickness (1 and 2 mm). Cortical bone was modeled by the material type #40 PCF (pound cubic feet, lb/ft3) with a mass density equal to 0.55 g/cm3. Three types of trabecular mimicking phantoms were considered (# 10, # 20, and # 30 PCF) equivalent to 0.16, 0.32, and 0.48 g/cm3, respectively. The commercial implants were 10 mm long and 4.1 mm in diameter. Different values of trabecular bone density and cortical thickness were considered to assess the effect of bone quality on the ultrasonic indicator and the ISQ. The effect of the implant insertion depth and of the final drill diameter was also investigated. The findings showed that the ISQ and the ultrasonic indicator increase and decrease, respectively, with the increase of the trabecular density, cortical thickness, and screwing of the implant. When the fixture diameter varies, the ultrasonic indicator values are significantly different for all final drill diameters (except for two), while the ISQs are similar for all final drill diameters lower than 3.2 mm and higher than 3.3 mm. Each QUS measurement was done 10 times. Each RFA measurement was done 5 times in each direction. Three implants were considered when studying the effect of varying each property. The results showed that the error on the estimation of the parameters using the QUS device was 4–8 times lower than those associated with the Osstell.

In structural health monitoring, the EMI method exploits the relationship between the electrical impedance of a piezoelectric lead zirconate titanate (Pb[ZrxTi1-x]O3) wafer transducer, simply abbreviated PZT, and the mechanical impedance of the host structure to which the PZT is bonded or embedded. It has been demonstrated by many that the value of the admittance, which is the inverse of the impedance, is a function (among other variables) of the stiffness and mass of the host structure. Any changes in the admittance are thus indicative of the presence of structural damages, provided the physical characteristics of the bonding layer and the PZT remain constant. When a PZT bonded to or embedded in the structure to be monitored is driven by an alternating electric field, a small deformation is produced in the structure. The dynamic response of the structure around the transducer is transferred back to the PZT and “interpreted” in the form of the electrical admittance, which consists of the real term known as conductance (G) and the imaginary term known as susceptance (S). A plot of G and S as a function of the actuation frequency present peaks that correspond to the structure’s modes of vibrations and to the PZT-adhesive-structure system, and they can be used for diagnostics [110–115]. Although the application of EMI in bioengineering were presented earlier [116–118], its application in dentistry was reported for the first time in 2011 by Boemio et al. [102] who proposed to bond one PZT to the abutment of the implant to be monitored and measure the electrical conductance of the transducer in order to infer the health of the surgical site. The work was followed by another one [103], shortly after. In both studies [102, 103] the authors investigated the feasibility of the EMI to assess the stability of dental implants. Two kinds of implant were inserted in high-density Sawbones®: the first implant, hereafter indicated as the short implant, was 2.9 mm in diameter and 10 mm long; the second, hereafter indicated as the long implant, was 5 mm in diameter and 15 mm long. Circular (Ø = 3.175 mm and 0.1905 mm thick) and square (2 × 2 × 0.267 mm) PZTs were glued to the short and the long implants, respectively. The samples were immersed in a glass container partially filled with a solution of nitric acid ([w/w] = 68–70%) to degrade the foam. This protocol simulated the reverse of bone-healing. The degradation was monitored for 12 h by measuring the admittance of the PZTs with a LCR meter. The conductance signatures were compared to the baseline signature, taken at the beginning of the experiment when the sample was just immersed. The baseline could be interpreted as the fully stable implant. The results demonstrated a monotonic relationship between the PZT conductance and the Sawbones degradation. When translated into the clinical evaluation of the bone-implant interface, the progress of healing increases the overall stiffness of the fixture due to the anchorage of the bone to the implant. Thus, the EMI indirectly infers the stiffness of the bone-implant system by measuring the admittance of a PZT bonded to the implant.

In two follow-up numerical [105] and experimental [104] studies, the stability of implants inserted in in vitro bovine bone samples was investigated. The observation of the osseointegration process was mimicked by monitoring the curing period of the root canal sealer inserted between the fixture and the sample. A PZT was bonded to the side of an abutment connected to an implant and the conductance of the transducer was measured. The results demonstrated that as curing progresses, the characteristics of the electrical conductance change. In other words, the EMI method was able to capture changes in the mechanical interlocking between the fixture and the surrounding bone. Numerically, the EMI-based method was modelled using a simplified finite element model to evaluate the effects of the interfacial tissue on the electromechanical response of a PZT patch bonded to an abutment [104, 105]. The modulus of the tissue was varied from 25 MPa (namely 10%) to 250 MPa (namely 100% fully osseointegrated), with increments of 10%. The lower modulus value was used to simulate advanced osteoporosis. A coupled field analysis in ANSYS was used to predict the conductance of the PZT as a function of the excitation frequency. The 10-node tetrahedral coupled-field Solid-98 element and the 10-node tetrahedral structural Solid-187 were used to model the transducer and the structure, respectively. The results demonstrated a gradual shift towards higher frequencies and a monotonic dependence on the interface stiffness.

In non-destructive evaluation applications, the acoustic emission (AE) method exploits the propagation of transient elastic waves generated by the rapid release of energy from a localized source or sources within a specific material. The elastic energy propagates as a stress wave (AE event) in the structure and is detected by one or more AE sensors [119]. Ossi et al. [106] proposed the use of AE and ultrasound to assess the quality of implant–bone interfaces and to monitor for micro-damage leading to loosening. They tested in vitro bovine rib bones using the conventional pencil lead breaks as an AE source. The test samples consisted of various synthetic materials, and fresh, dried and hydrated bones. For the experiments with the bovine rib, the pencil lead source was triggered on a temporary abutment loaded on the implant, and a commercial AE sensor was mechanically held on the bone. Eleven rib bones were selected, in each of which four bone-level U-Impl titanium dental implants were installed. The size of the implants were 8.5 mm × 3.5 mm (diameter), and 13 mm × 4.5 mm. The AE energy, defined as the time integral of the detected waveform within an user defined time interval, was the primary parameter considered for the analysis. The results showed that the transmission of AE energy through the samples is dependent on the degree of hydration of the bone. It was also found that perfusing samples of fresh bone with water led to an increase in transmitted energy, but this appeared to affect transmission across the interface more than transmission through the bone. The reason behind this empirical evidence is that water acts as a couplant between the implant-bone system and the AE sensor. In addition sound propagates with less attenuation in water than in porous materials. Although paper [106] showed a novel approach to the assessment of bone implant interface and a few other studies followed [107, 108], its practicality in a clinical setting and its superiority with respect QUS, RFA, or Periotest® have still to be demonstrated.

The connection of an abutment to its fixture is a key factor affecting the stability of the osseointegration regarding dental implants. The gap between these two components is an ideal environment for bacterial proliferation which may lead to infection and bone loss. The gas permeability method aims to evaluate any gap between an implant and its abutment [109]. In the work of Torres et al. [109], an implant and its abutment were put in a cylindrical pressurized container to quantify the tightness of the connection. In a second experiment, four 12 mm long and 4.3 mm in diameter implants were tested with the aim of evaluating any leakage of the implant-abutment connection. Owing to the complexity of the setup, the gas permeability method seems to be a quantitative, reproducible and practical method to assess dental implant-abutment leakage but only in vitro.

Transcutaneous osseointegrated prostheses

Clinical challenges

In the U.S., more than two millions people suffer from traumatic limb loss [120, 121]. With limited options for these patients to integrate back into society at the same level as before, the most common remedy for lower limb amputations is the use of socket prostheses. A socket prosthesis is essentially a pipe attached to a socket matched to the residual limb through a gel liner. However, the use of this kind of prosthesis for extended periods of time may lead to the problems discussed in the Introduction. Ultimately, this approach commonly fails in patients with multiple limb loss or short residual limbs [122, 123]. In the military population, this problem is particularly relevant because blast-related heterotopic ossification, which is the bone formation at an abnormal anatomic sites, within the soft tissues of the residual limb can make successful socket fitting difficult or impossible [123, 124].

Percutaneous osseointegrated prosthetics or bone-anchored prosthetic implants have been developed in the last two decades as an alternative for patients that experience extreme discomfort with socket prostheses. The prosthetic is connected directly to the bone, so the soft tissue interface of the socket prosthesis is no longer present. An osseointegrated implant transfers load directly from the skeletal system to the artificial limb, and provides stable connection to the skeleton while eliminating skin lesions experienced with socket prosthetics. In addition, transcutaneous osseointegrated prostheses enhance osseoperception, which is the sensory feedback from the environment [125].

While osseointegrated prostheses eliminate many of the drawbacks associated with socket prostheses, they have their own set of limitations and clinical challenges [120]. First, an extensive rehabilitation is required [126, 129]. The patients need to be trained to progressively load the prosthesis which is believed to accelerate the osseointegration process. Then, the infection caused by biofilms entering the limb via the prosthesis [120] should be avoided because these infections are among the leading causes of osseointegrated prosthesis failure. As such, it is important to examine the interface between the skin and the device. Skin does not naturally bond to the foreign object thus bacteria often leads to the breakdown of the skin at this location. Regular cleaning of the location where the rod exits the body is required and when a skin infection does occur, an antibiotic is often sufficient to remove the infection. These infections often can spread to the bone and degrade the portion of the bone integrated around the titanium rod leading to the loosening of the prostheses. This may ultimately require the removal of the implant and a new surgical procedure. To reduce the risk of infection, the prosthesis may be covered with an antibacterial coating; alternatively, the skin is forced to better adhere to the implant. Another drawback is the therapy failure related to bone remodeling and implant insertion in the medullary canal. Bone remodeling is the shifting of bone thickness over time due to stress or strains acting on the bone. It is known that mechanical loading is one of the biomedical stimuli in bone remodeling [134]. Loading due to normal gait induces repeated strain on the host bone and this triggers bone remodeling, which ultimately may trigger bone fracture or fixture loosening during the life of the prosthesis. As the medullary canal does not naturally grow inward, long term stability of the implant can be in jeopardy in youth or highly active patients, as the medullary canal expands through development ages and the muscles constantly pull at the bone which both can cause an increase on the medullary canal diameter. For all the above there is a growing need to monitor the integration and the long-term performance of osseointegrated prostheses.

In the U.S. the use of osseointegration prostheses was approved in 2015 by the Food and Drug Administration for above-the-knee amputees and for humanitarian indications only [14]. To date, there are several different fixture designs. The first one is a screw-type fixation (Fig. 6), similar to dental implants, and developed by a Swedish group led by Brånemark in the 1990s. The system is known as Integrum OPRA (Osseointegrated Prostheses for the Rehabilitation of Amputees) and its insertion is a two-stage surgical procedure: in the first stage, a threaded titanium implant is inserted into the medullary canal of the femur, and the soft tissue is closed around the end of the limb; 6 months later, a titanium abutment is attached to the osseointegrated fixture. The prosthetic components are connected to the abutment around which the soft tissues and skin are closed. The rehabilitation protocol involves gradual loading of the bone-implant interface over a period of 6 months to stimulate and facilitate the process of osseointegration [11, 126]. The second design, termed Integral Leg Prosthesis (ILP), was developed in Germany and consists of an intramedullary press-fit, porous-coated, alloy device similar to the one used in joint arthroplasty. In 2011, a third model, shown in Fig. 7, was introduced by Al Muderis and is known as the Osseointegrated Prosthetic Limb (OPL). It is similar to the ILP with a highly polished smooth transcutaneous dual cone adaptor coated with titanium oxide to minimize soft-tissue friction [11]. The OPL includes a distal flare within the intramedullary portion to assist with bone anchorage [127]. OPL also requires two surgeries, approximately 4–8 weeks apart. First, the soft tissues are prepared with refashioning of the residual limp, excess subcutaneous fat is excised, neuromas are removed, and the bone is prepared to accept the implant. The intramedullary component of the prosthesis is then inserted. Second, the transcutaneous dual-cone adaptor is inserted while externally, it is fixed to a torque control safety device, which then connects to the prosthetic limb [11, 128]. The rehabilitation protocol associated with the OPL is called OGAAP-1. The same Australian group proposed a single-stage procedure that begun to be routinely performed since 2014 [14]. This protocol, which has been named OGAAP-2, reduces the overall time required for the definitive osseointegrated reconstruction and rehabilitation to ~ 3 to 6 weeks [14]. As pointed out by Hebert et al. [11] any evaluation of this fourth design shall be waived until publication of the prospective 2-year follow-up data. There are a few other implant designs that are reviewed in [146].

Fig. 6.

The Integrum OPRA system. Figure adapted from https://integrum.se/opra-implant-system/are-you-a-potential-candidate/transfemoral-above-knee-amputations/ (Date accessed 07 August 2019)

Fig. 7.

Photos of the OPL implant system commercialized by Permedica s.p.a. (Italy) and used for the OGAAP-2 procedure. Figure from Ref. [14]

The rehabilitation could be expedited if the stability of the prosthesis in the host bone would be monitored or at least evaluated periodically. If physicians could accurately assess the degree of osseointegration and or the degree of bone remodeling, the structural stability of the device would be reliably evaluated [129, 130]. The noninvasive evaluation methods would greatly reduce the risk of bone fracture and implant loosening.

Monitoring methods

To date, the most common non-invasive approach to evaluate the health of an implant is by X-rays. Radiography is used to image the prosthesis and its host bone. The analysis of the images is qualitative and subjected to the experience of the care providers. The fixture to bone interface is subjected to image diffraction caused by the presence of the titanium elements [131]. Other limitations about X-rays are the need to be performed in a clinical setting with expensive machinery by exposing the patient to radiations [132, 133].

The use of radiographic methods and CT scans is also conducted during the pre-operation phase in order to determine the anatomy of the skeletal residuum, as well as to allow patient-specific selection of the implant type and size, and external prosthetic components [14].

Xu and Robinson [133] investigated bone remodeling by combining finite element method (FEM) and X-ray images. The clinical medial–lateral X-rays of 11 patients were reviewed. The images were converted into a digital format and geometrical correction was carried out in order to eliminate geometrical distortion of different X-rays. FEM was used to investigate the effect of stress/strain distribution in the femur on the bone remodeling and to provide a biomechanical interpretation of the remodeling. The radiographic images showed cortical bone growth around the proximal end of the implant and absorbtion at the distal end of the femur. The study confirmed that the bone remodeling in a femur with a fixture was influenced by stress/strain redistribution across the fixture-bone interface.

CT and X-ray were used in a numerical/experimental study based on FEM to evaluate the effects of bone remodeling on a male amputee with an OPRA implant [134]. The initial FEM model of the implant was reconstructed using pre-surgery CT scan images, and then updated 31, 52, and 68 months after the surgery using X-ray images that provided a measure of the bone thickness change. The thickness at each point was the average of three measurements. Since the X-ray images can only provide lateral-medial bone thickness, the change around the periphery was approximated by interpolation. A few limits of the study, as pointed out by the same authors, were the exclusion of the cortical bone density change in the model. In addition, the bone thickness change was interpolated because more accurate information via the X-ray was not attainable. Last but not least, the loading rate and number of cycles per day were not taken into account. Nevertheless, the study demonstrated that significant bone remodeling occurred and this caused significant strain re-distribution along the longitudinal direction of the femur. The results suggested that implants made with functionally graded materials may be preferable to a homogeneous material [134].

It is noted here that other studies were found in the literature, pertaining to the use of FEM to predict load transfer and/or strain distribution. However, they were not included in this review if not accompanied by the use of noninvasive methods to assess/estimate such stresses and strain.

The principles of the RFA have been extended to the evaluation of trans-femoral implants. One of the earliest studies was presented in [135], where the resonant characteristics of implants (17 and 18 mm in diameter) embedded in a synthetic femur model made of Sawbones, and in an above knee amputee were empirically observed. In both cases, a small pendulum was used to trigger excitations that were then measured with an accelerometer attached to the tip of the implant. The signals were analyzed using a Fast Fourier Transform software to extract the fundamental natural frequency of the implant. The in vitro study was conducted using different silicone rubbers to mimic different interface conditions. The findings showed that the fundamental natural frequency is proportional to the elastic modulus of the interface material between the implant and the Sawbones. The in vivo study showed that the frequency decreased after the initial weight bearing rehabilitation, returned to the preloading level at around day 24, and then increased to become steady 38 days after the first weight bearing exercise.

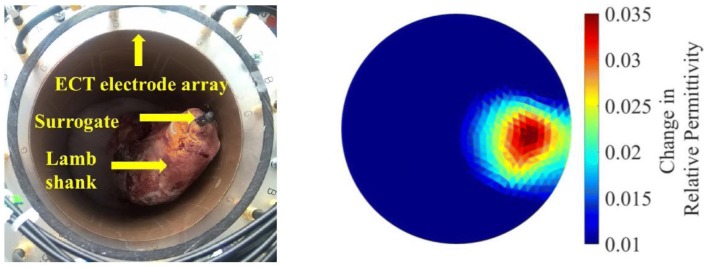

Another approach to evaluate the progression of osseointegration is based on strain measurements. A group of researchers at the University of California, San Diego has been working on a noncontact, imaging system for monitoring the strain of osseointegrated prostheses [129, 136, 137]. The method comprises of two steps. First, a passive thin film, designed such that its electrical permittivity is significantly dependent on axial load, is deposited onto the prosthesis surfaces as an external coating. Second, an electrical capacitance tomography (ECT) measurement technique and reconstruction algorithm is adopted to capture strain-induced changes of the coated implanted prosthesis. ECT is a non-invasive imaging technique based on the estimation of the electrical permittivity distribution within a predefined sensing region [138]. It requires an array of equidistantly spaced electrodes arranged along the perimeter of a circular sensing region. An electrode is excited with an alternating current signal, while the capacitance between the excitation and other electrodes are measured. The electrode used for excitation is switched, and capacitance measurements at all other electrodes are acquired. This process is repeated until every electrode is excited. The setup is completed by a data acquisition system that controls the array and stores the measurements for post-processing analysis and image reconstruction. The method was demonstrated in prosthesis phantoms subjected to different loading scenarios and in a lamb shank (Fig. 8) with an embedded prosthesis phantom [129]. The results showed that the ECT, when coupled with strain-sensitive nanocomposites, could quantify the strain-induced changes in the dielectric property of thin film-coated prosthesis phantoms. In addition, it was found that the permittivity varies linearly through the thickness of the specimen in a similar manner as one would expect for a cantilevered beam under bending. Leveraging upon the success of these studies, more research is warranted to develop a wearable noncontact strain monitoring system and conduct clinical trials.

Fig. 8.

a Testing a method based on ECT and a strain sensitive thin-film nanocomposite on a prosthesis phantom inserted in a lamb shank. b Change in the electrical permittivity distribution within the ECT electrode array. Figure from [129]

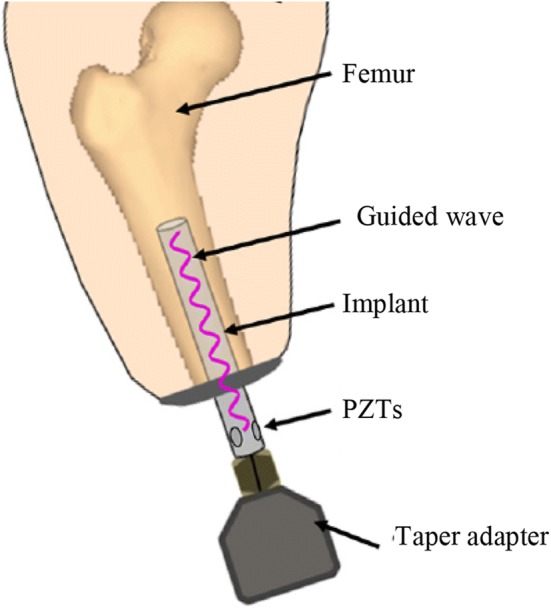

The use of nano-based or other types of sensors as proposed by Gupta and co-authors [129] would be challenged by issues such as biocompatibility, cost of sensor placement, long-term survivability of the sensor itself, and regulatory review process [120]. A viable alternative to embedded sensors may be offered by placing a few sensors outside the body. To this end, Lynch and his group [120, 121] proposed the use of guided ultrasonic waves (GUWs), according to the scheme shown in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Schematic of the guided ultrasonic wave based method proposed by Wang and Lynch [120]. Image adapted from Ref. [120]

GUWs are popular in SHM because they enable the periodic inspection or the permanent monitoring of large areas using a single probe attached or embedded to the structure to be monitored while maintaining high sensitivity to small flaws. GUWs can travel relatively large distances with little attenuation and they offer the advantage of exploiting one or more of the phenomena associated with transmission, reflection, scattering, mode-conversion, and absorption of acoustic energy [139–142]. To interrogate the bone–prosthesis interface Wang and Lynch [120] studied numerically (FEM) and experimentally the use of the first longitudinal GUW mode to determine the degree of osseointegration of a titanium rod inserted into a femur Sawbones and the resistance to pull-out during a pull-out experiment. In both experiments, eight piezoelectric transducers were bonded on the surface of the percutaneous end of the prosthesis. Four PZTs acted as transmitted, four acted as receivers. The first experiment investigated the changes in the energy of the first longitudinal GUW mode as a result of bone healing, which was mimicked with a 30-min epoxy applied to the bone–prosthesis interface. It was found that the energy decreases by nearly half during the healing process. The second experiment aimed at evaluating the ability of the same wave energy at identifying fixture loosening, which is why about 5–7% of implants have to be removed. It was found that the wave energy increased as the osseointegrated fixture loosens and is withdrawn from the bone. Both finite element models agreed well with the experimental data. As the bone integrates with the implant, more acoustic energy leaks into the limb and therefore less ultrasonic energy is reflected back to the sensors located outside the limb.

The same group at the University of Michigan applied the same GUW-based setup to detect and locate fracture in the host bone of an osseointegrated prosthesis [120, 121, 143]. A 15.9 mm diameter and 156 mm long titanium rod was inserted inside a Sawbones femur. At the external end of the rod, eight 12 × 4 mm2 PZT wafers were arranged in two circumferential arrays: four transducers acted as transmitters and the remaining as sensors. The setup was also modeled using FEM. To mimic the bone fracture, a longitudinal crack was set on the bone model by cutting its geometry. The crack was 25.4 mm long and 0.2 mm wide. A three-cycle Hanning window 100 kHz tone-burst was excited to induce the first flexural mode. The FEM results showed that the strain fields associated with the flexural wave scatter from the bone fracture, i.e. the strain field is changed by the bone fracture. This was observed by noting some differences on the time waveforms recorded with the four sensors. The authors suggested that bone fracture can be identified by extracting the difference signal from the healthy baseline case to the case with fracture. Besides baseline subtraction, the time-of-flight of the waveforms was investigated to quantify any effect of the bone fracture. By conducting a joint time–frequency analysis based on the Gabor wavelet transform, Lynch et al. [121] found a difference in the arrival times of the flexural mode due to the location of the fracture.

Another effort by Lynch’s group [121] was the development of biocompatible thin film sensors to monitor the mechanical behavior and to measure strain. The film sensors were conceived for in vivo placement in the host limb. The study involved additive thin film manufacturing of lithographically patterned materials on biocompatible thin film substrates to create an array of sensing transducers capable of measuring strain and bone growth. Inductive wireless interfaces were integrated in the thin film sensors to provide a means of powering and reading sensor outputs from outside the limb. The in vivo and ex vivo sensing strategies were unified into a single monitoring system through the use of a compact wireless sensing node that interrogates the in vivo sensors (through inductive coupling) and ex vivo sensors. For the sake of space more details cannot be provided here but the interested reader is referred to Sections 5 and 6 of Ref. [121].

Conclusions

In this article a review of the most popular and emerging noninvasive techniques to evaluate the stability of dental and trans-femoral implants was provided, with a special focus on biomechanical methods. A discussion about advantages and limitations of each method was provided based on the outcomes of the cases presented. The review about the emerging technologies covers the developments of the last decade, while the discussion about the clinically approved systems focuses mostly with the latest (2017–2018) findings.

The studies presented in this paper about the evaluation of dental implants can be clustered in two large groups: commercial systems adopted clinically, and emerging technologies that have not been approved yet by regulatory agencies or still at the development stage. Most of the 2017 and 2018 publications relative to the first group seem to be repeating each other with little scientific breakthrough. As a matter of fact, these publications compare two or more among the ISQ, PTV, IT, and reverse torque under certain conditions in terms of operators experience, implant type (i.e. length and diameter), and samples number. Given that more than 1000 different implant systems have been introduced to the market most of which, according to [34], have been designed without any previous research or scientific background, there are virtually infinite possibilities about testing combinations. Overall, the 2017–2018 studies provided relevant and significant information about the comparative clinical performance among Periotest®, RFA, and torque-based techniques. However, it is this reviewer’s opinion that there was not any significant scientific breakthrough. In terms of emerging technologies, the review included the last decade of research and developments. Although some of these techniques, such as the quantitative ultrasound method, seems to be mature, they will have long time to be widely accepted by the medical community after obtaining regulatory approval. Other emerging technique still needs lot of lab data to prove repeatability under a wide variety of implant designs. As such, a general formulation and analysis of any noninvasive methods is hard to attain.

Transcutaneous osseointegration faces several clinical challenges that were summarized in [125]: implants need to be adapted to patients’ specific anatomy; a controlled and gradual rehabilitation period lasting 12 months is required to avoid fibrous ingrowth into the implant that could result from excessive loading and micromotion; proper healing requires some motion at the bone-implant interface for proper healing [8] that however cannot be excessive because large micromotion can lead to the development of a fibrous tissue interface rather than a bone interface; infections need to be prevented. Despite these limitations, the advantages of the osseintegrated prostheses seems to be superior to advantages of the socket prostheses. To mitigate the shortcomings of osseintegrated prostheses for the treatment of lower limb loss, bio-chemical–mechanical methods shall be developed to: (1) evaluate/monitor the progress of the osseointegration process, (2) detect infections at the earliest possible stage, and (3) quantify stress/strain distribution. Research in monitoring strategies shall also be accompanied with producing patient specific implant geometries to produce custom surface textures for bone ingrowth or ongrowth using, for instance, additive manufacturing methods, as proposed in [125].

Regardless of the clinical scenario, either implant dentistry or orthopedic fixtures, future studies may take advantage of the emerging area in big data and data mining in order to develop algorithms able to predict the failure of dental or orthopedic implants. These algorithms shall take into consideration the wide-ranging scope of surgeries, patients’ body conditions, patients’ systemic diseases, operation methods, prosthesis types, surgeons’ experience, and implant design to predict the outcome of the treatment and reduce the risk of failure. Two examples are the recent works presented in [144, 145]. The first group developed a prediction model based on supervised learning techniques for providing an early warning mechanism for dental implant failure [144]. The second group conducted a retrospective study to assess the risk factors associated with early and late implant loss at the patient- and implant-based analysis [145]. A total of 18,199 patients received 30,959 dental implants were considered and parameters such as age, gender, jaw, location, implant brands, implant length and diameter, bone augmentation procedures, and the number of implants placed per patient were recorded. A multivariate generalized estimating equation logistic regression was used to identify risk factors related to both early and late implant loss. The conclusions of the study emphasized that male patients, older patients, and implants placed in the mandibular anterior were considered as risk factors for early implant loss, whereas male patients, older patients, bone augmentation, and short implants were considered as risk factors for late implant loss.

Other strategic developments may be the integration of two or more sensing methods to augment the reliability and accuracy of osseointegration diagnosis or the introduction of engineering methods widely adopted in the area of nondestructive evaluation and structural health monitoring that have not being fully exploited in bioengineering.

Acknowledgements