Abstract

Setting

Montréal.

Intervention

The lack of common knowledge about what public health does is a hindrance to its recognition and capacity to act. Montréal’s regional public health department set an explicit goal to clarify and better communicate its specific contributions when it developed its 2016–2021 action plan. This article briefly describes the efforts made to classify public health practice, introduces a typology of public health interventions and discusses its application and benefits.

Outcomes

The typology that was developed defines 29 types of interventions grouped into four categories: direct action targeting the population; advocacy (persuading partners to take action); support (helping partners take action); collaboration (taking action with partners). The analysis of Montreal’s most recent action plan, completely drafted in terms of the typology, provides an insightful characterization of public health practice. Globally, four out of five interventions target partners (indirect), with more than half falling within the support category. Other indirect interventions are divided almost equally between advocacy and collaboration. Following a rigorous planning process and enforcing the use of the typology also had a significant structuring effect on the organization and its teams and enabled greater synergy with partners from other sectors.

Implications

Very few people are familiar with everything public health does, sometimes not even the responsible political decision-makers. This situation poses a threat to the survival of its prevention mission. The typology of public health interventions is an innovative tool that can be used to better inform the public and decision-makers.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.17269/s41997-019-00268-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Typology, Public health interventions, Public health services, Planning

Résumé

Lieu

Montréal.

Intervention

La méconnaissance de ce que fait la santé publique limite à la fois sa reconnaissance et sa capacité d’agir. Lors de l’élaboration de son plan d’action 2016–2021, la direction régionale de santé publique de Montréal s’est donnée pour objectif de clarifier et de mieux communiquer ses contributions spécifiques. Cet article décrit brièvement les efforts réalisés pour catégoriser la pratique de santé publique, présente une typologie des interventions de santé publique et discute de son application et de ses retombées pour Montréal.

Résultats

La typologie qui a été développée définit 29 types d’interventions regroupés en quatre catégories : l’action directe auprès de la population; la mobilisation (convaincre des tiers d’agir); le soutien (aider des tiers à agir); et la collaboration (agir ensemble). L’analyse du plus récent plan d’action de Montréal, entièrement rédigé en termes de la typologie, donne un portrait éclairant de la pratique de santé publique. Globalement, quatre interventions sur cinq ciblent des tiers (action indirecte), plus de la moitié de celles-ci étant dans la catégorie soutien. Les autres interventions indirectes se répartissent presque également entre la mobilisation et la collaboration. Le fait de suivre un processus de planification rigoureux reposant sur la typologie a eu un effet structurant significatif sur l’organisation et ses équipes, tout en menant à une plus grande synergie avec ses partenaires d’autres secteurs.

Implications

Très peu de gens sont familiers avec l’éventail des contributions de la santé publique, pas même les décideurs politiques qui en sont responsables. Cette situation constitue une réelle menace à la survie de sa mission de prévention. La typologie des interventions de santé publique est un outil novateur pour mieux informer la population et les décideurs.

Mots-clés: Typologie, Interventions de santé publique, Services de santé publique, Planification

Introduction

Since the adoption of the Ottawa Charter in the 1980s, the scope of public health action has expanded considerably and become more complex. However, perceptions of its role have not evolved at the same pace. While it is widely known that school nurses vaccinate children in schools, the same cannot be said about professionals working with municipal authorities to implement traffic calming measures or improve access to healthy food in underserved areas, or those focusing on putting into effect non-smoking policies in health facilities. This lack of knowledge about what public health teams do, about how they contribute to improving determinants of health, is a hindrance to their recognition and capacity to act. Why though does this situation prevail?

One reason is that public health teams often work behind the scenes, collaborating with those who have the levers to make changes favourable to health, such as municipalities, the education and daycare sectors, employers, the health network and community groups. Their role is usually to support or influence these stakeholders. In its guidance documents (e.g., Québec Public Health Program, regional action plans), many interventions are described as intentions (e.g., foster, support) rather than commitments. In situations where one does not have full control, it is safer to avoid committing to specific outcomes. However, failing to at least commit to specific means makes it more difficult to grasp, and recognize, public health’s contributions, which may appear to lack substance.

Another explanation lies in terminology. Over time, words stemming from various disciplines have been incorporated into the language of public health. These terms come from diverse fields, such as community organization, sociology, psychology, kinesiology, nutrition, education, andragogy and urban planning, as well as from various successive trends in management and governance. This hodgepodge of multidisciplinary culture sometimes gives rise to borrowed terms being not fully understood, resulting in a lack of clarity (Gagnon et al. 1999). This is particularly the case for French terms like “concertation” (consultation and cooperation) or “accompagnement” (guidance), used abundantly to mean very different things in various fields.

In light of this state of affairs, Montréal’s public health department (Direction régionale de santé publique or DRSP) set an explicit goal to clarify the specific contributions of public health actors and to better explain and convey information about their interventions when it developed its 2016–2021 Integrated Regional Public Health Action Plan (Direction régionale de santé publique, CCSMTL 2017). In particular, it developed a typology for public health interventions. This article briefly describes the efforts made to classify public health practice, introduces the typology that was developed and discusses its application and benefits for Montréal.

Towards a typology of public health interventions

Classifying public health interventions

A literature search shows there is no typology of interventions in public health practice comparable with the one developed in Montreal,1 which aims to clarify the means deployed by public health staff in order to achieve specific goals with respect to the health of the population. Many descriptions of public health’s essential functions define its scope of activity and main approaches, typically including surveillance, promotion, prevention and protection (Turnock et al. 1998; World Federation of Public Health Associations 2016; Health Canada 2003; Gouvernement du Québec 2015; British Columbia, Ministry of Health 2017), but do not classify the actions that public health teams undertake. A multidimensional classification of public health activities comes closest (Jorm et al. 2009). The authors define six classes: functions, health issues, determinants of health, settings, methods, and resources and infrastructure. They then propose subclasses. For the “methods” class, Jorm et al. identify 35 subclasses or broad categories, some of which are not specific to public health (e.g., diagnostic, research and evaluation, treatment methods, political action, legislation and regulation, social action). Although it identifies a set of methods specific to different sectors that can impact public health, Jorm et al.’s classification does not recognize the specific contributions of public health teams.

Developing the tool

The typology of public health interventions stems from an initiative of the principal author, to which contributed a dozen professionals, medical specialists and administrators at Montréal’s DRSP. In 2006, an initial typology of public health interventions was developed inductively, based on an analysis and categorization of actions in the previous regional action plan (Régie régionale de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal 2003) and on several frameworks, including the Ottawa Charter and the Québec Public Health Act. It proposed 12 types of actions or programs, each associated with one or several functions (health promotion, prevention, protection). At this early stage, three types were used to describe the nature of public health’s work with its partners from other sectors. Moreover, actions targeting the population were distinguished from activities that precede and inform those actions (such as surveillance) and from other activities common to most public organizations, such as planning, evaluation, research and continuous improvement. This initial version of the typology of public health interventions was used for operational planning of local public health activities, in the wake of a reorganization of the province’s health network, which required merged institutions to redefine their services. Nearly a decade later, the typology of public health interventions gained new momentum when it was proposed as a foundational tool to develop Montréal’s upcoming 2016–2021 regional action plan.

As part of this work, the first version of the typology was thoroughly revised. In consultation with DRSP teams, a small group of experts compiled an updated list of interventions based on services described in the 2010–2015 regional action plan (Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal 2011). This process prompted further reflection on public health’s role vis-à-vis third parties and led to the will to clearly distinguish between direct and indirect actions of public health. Indeed, a feature peculiar to public health practice is derived from the fact that practitioners act as both service providers (direct action) and, to a greater degree, as facilitators working with many actors or third parties (elected officials, administrators, professionals, etc.) who have the power to act on determinants of health (indirect action). In this second category, it was also recognized that different situations call for different stances, which led to differentiating three subcategories of indirect action: advocate, support and collaborate. Defining the types of interventions within each category was the last step of the process. The tool was then passed on to the teams responsible for planning services to be offered. An iterative process with the latter helped further delineate the contours of the typology and led to refined definitions and the addition of a few types of interventions.

Typology of public health interventions

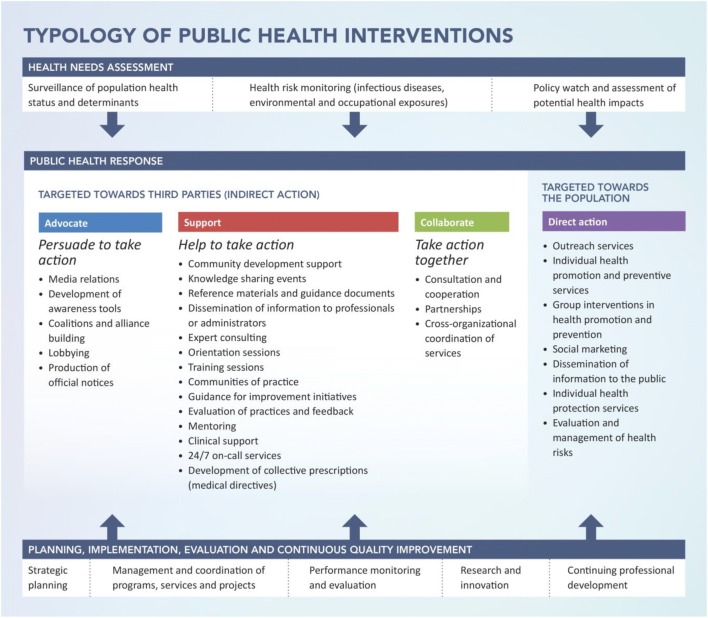

According to the typology, a public health intervention is defined as an organized set of means implemented in a specific context to meet one or several targets with respect to improving health and preventing disease. This definition limits the notion of a public health intervention to the means intended to act on the health of the population, and encompasses health promotion, prevention and protection. It excludes preliminary efforts to assess and analyze the needs of the population, such as surveillance of the population’s health status and determinants of health, health risk monitoring, and policy watch. Activities related to planning, implementation, evaluation and continuous quality improvement are not included as public health interventions either, even though they mobilize resources. Figure 1 outlines, lists and situates public health interventions within the DRSP’s activities. Full definitions developed for each type of intervention within the typology can be found in the Supplementary Annex.

Fig. 1.

Typology of public health interventions

The typology includes two broad categories: (1) interventions targeted directly towards the population, including services provided by public health staff to individuals and groups, and (2) interventions targeted towards third parties who work with the population, and therefore carried out indirectly by public health teams.

Direct action targeted towards the population

Similar to other health and social services care providers, direct public health action includes seven types of interventions: (1) outreach services; (2) individual health promotion and preventive services; (3) group interventions in health promotion and prevention; (4) social marketing; (5) dissemination of information to the public; (6) individual health protection services; (7) evaluation and management of health risks.

Indirect action targeted towards third parties

When public health intervenes indirectly by targeting stakeholders in other sectors, it adopts one of the following stances: (1) persuade to take action (advocate); (2) help take action (support); or (3) take action together (collaborate).

Persuade to take action, or advocate

This subcategory encompasses strategic interventions designed to persuade decision-makers to carry out actions and put in place conditions in order to improve population health. It contains five types of public health interventions: (1) media relations; (2) development of awareness tools; (3) coalitions and alliance building; (4) lobbying; and (5) production of official notices. All such interventions are typically preceded by a thorough context analysis to delineate underlying issues for public health and assess the position and power of relevant stakeholders, so as to develop a mobilization strategy and identify target groups.

Help take action, or support

This subcategory encompasses interventions that aim to provide assistance to third parties as they carry out activities to improve population health. Interventions to support various stakeholders involve knowledge sharing and providing guidance to improve professional and management skills. There are 14 types of interventions in this category: (1) community development support; (2) knowledge sharing events; (3) reference materials and guidance documents; (4) dissemination of information to professionals or administrators; (5) expert consulting; (6) orientation sessions; (7) training sessions; (8) communities of practice; (9) guidance for improvement initiatives; (10) evaluation of practices and feedback; (11) mentoring; (12) clinical support; (13) 24/7 on-call services and (14) development of collective prescriptions (medical directives). Several such interventions are usually combined, depending on needs.

Take action together, or collaborate

The third subcategory includes interventions that consist of working with partners in the health sector or other sectors of society to implement public health programs or projects to improve population health. There are three types of collaborative interventions between public health teams and one or several other groups of stakeholders: (1) consultation and cooperation; (2) partnerships, a more engaged form of collaboration which often involves a formal written agreement; and (3) cross-organizational coordination of services, when organizations are required to work together in order to fulfill their respective mandates.

Montréal’s 2016–2021 Regional Public Health Action Plan

A determinant-based planning model

To avoid preventable diseases, public health takes action on their causative factors, which we refer to as determinants of health. Determinants are usually part of complex causative webs and each is typically connected to many preventable diseases. Such is the case, for example, of lifestyle habits (diet, physical activity, smoking, etc.), which affect the development of multiple chronic illnesses. To maximize the impact of its actions through greater coherence and simplicity, instead of devising action plans for each preventable disease (e.g., cancer, cardiovascular disease), knowing that they would overlap, the DRSP decided to adopt an innovative planning model built around each key determinant of health. After modeling the linkages between determinants and outcomes, key data were gathered to characterize the current state of each determinant and each health outcome. Based on this information, a prioritization exercise involving internal and external stakeholders led to the selection of 30 key determinants that have a significant and direct impact on the health of Montréal’s population and that fall within the mandate of our regional public health department. These determinants encompass environmental factors (natural, built and social), behaviours and access to preventive services, but exclude upstream social determinants such as education, employment or income. An integrated public health service offer was developed for each determinant with the double aim of improving health and reducing inequities. Each service offer was conceived using a guide and standardized planning tools, including the typology of interventions.

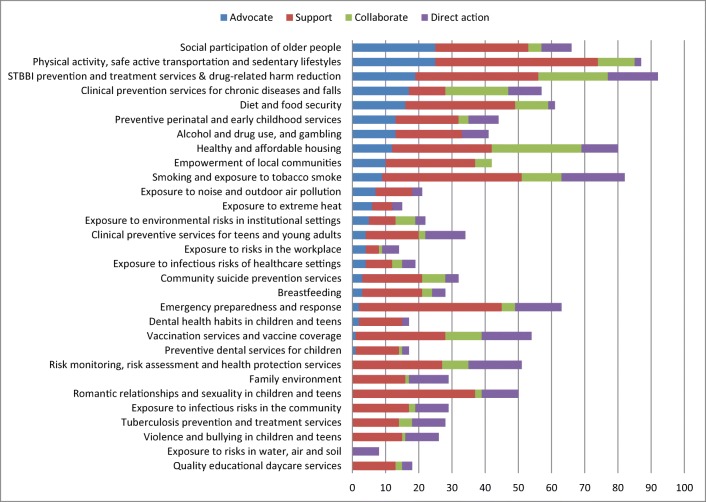

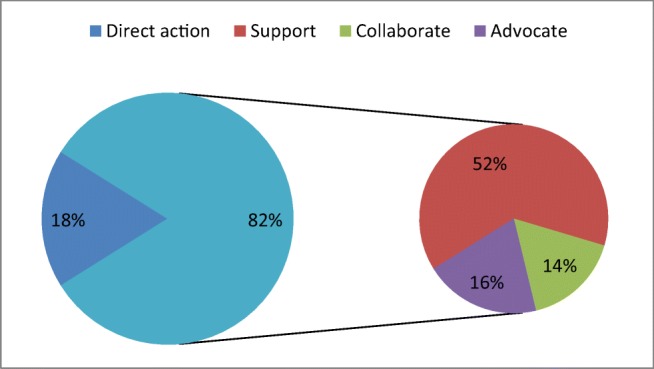

Below, we present an analysis of the resulting action plan, examining its content by category of interventions (Fig. 2) and by determinant (Fig. 3). This gives a broad outline of public health practice in Montréal. However, caution must be exercised when interpreting the results, as they are based solely on the number of interventions, which does not necessarily reflect the magnitude of efforts devoted in terms of human, financial and material resources.

Fig. 2.

Overall distribution of interventions, Montréal’s 2016–2021 Regional Public Health Action Plan

Fig. 3.

Number of interventions by category and determinant, Montréal’s 2016–2021 Regional Public Health Action Plan

Finding 1: Above all, support stakeholders who have the power to act

Globally, four out of five interventions in our action plan are targeted towards partners (indirect), with more than half falling within the support category. Of the 30 determinants in our plan, 29 include interventions of this category. Expert consulting clearly tops the list of support interventions, followed by producing reference materials and guidance documents, and, in third place, supporting community development and knowledge sharing events. Other indirect interventions are divided almost equally between advocacy and collaboration.

The fact that such an important part of public health’s work is carried out behind the scenes, with other actors having forefront visibility, no doubt emphasizes the need to better define and communicate public health’s role. Though public health has less control over outcomes when it intervenes indirectly, it can nevertheless be held accountable for the means it deploys to ensure others take the appropriate action to achieve the outcomes public health seeks.

Finding 2: Some stakeholders already work to prevent, while others must be persuaded

The importance of advocacy interventions varies greatly among determinants (Fig. 3), depending on the ideological distance between public health and those who have the levers to take action.

In some cases, partner networks are already highly engaged on specific determinants; thus, public health advocacy is not necessary and its role focusses on support. This is the case of the education sector and of associated determinants, such as Preventive dental services for children and Clinical preventive services for teens and young adults. In other cases, there is a clear legal framework supporting the direct action by public health, for example in the face of threats that can have serious health consequences. Such determinants include Tuberculosis prevention and treatment services and Health protection and risk monitoring, investigation and evaluation services.

However, advocacy interventions are indispensable when seeking to innovate, for example in the case of determinants like Social participation of older people, or of specific interventions, like supervised injection services. In Montreal, advocacy interventions are prominent with municipal stakeholders (elected officials, administrators and various municipal authorities) to ensure they consider public health issues in the decision-making process. Within the City of Montréal, its 19 boroughs and 14 linked cities, many different entities are involved in land-use planning and regulation, through which they shape lifestyle habits and behaviours (e.g., eating habits, physical activity linked to transportation and recreation), affect the risks to which the population is exposed (e.g., air pollution, road accidents), and even change living conditions (e.g., healthy and affordable housing).

Last, advocacy interventions are also needed when there are competing interests, especially in the health sector. The stress on curative services means that it is a challenge for Montréal’s health and social services network to deliver all preventive services. One example is Preventive perinatal and early childhood services, which are not readily accessible to everyone. Given the lifelong impacts of early development, public health is devoted to convincing decision-makers to improve the situation as quickly as possible.

Finding 3: Direct action is widespread, though not associated with public health

About one in five interventions directly targets the population (Fig. 2), the most common ones being individual and group health promotion or disease prevention services. Direct services to the public are present in all determinants but one, Empowerment of local communities. Although these services are part of our public health program, they are delivered by clinical staff working in primary care networks. The most common preventive services—vaccination, for one—are not dispensed under public health’s branding, even though they are its responsibility. This partly explains why the population and even political decision-makers are not familiar with public health and it undermines the precarious position of prevention within our health system. Public health would certainly benefit from greater exposure and more recognition for its contributions (Guyon and Perreault 2016).

Outcomes of the typology of public health interventions

The typology was used to write Montréal’s 2016–2021 Action Plan. Working groups covering 30 determinants of health used the tool to label their interventions and define their service offer. This confirmed that the typology is both exhaustive in scope and sufficiently granular to describe actual subtleties of public health practice in a variety of domains, thus demonstrating its usefulness for planning.

This rigorous planning process has had a significant and concrete impact on the organization and its teams working in different fields. Montréal’s efforts to define and classify public health interventions with a standardized typology have enabled it to better define the nature of its activities and to structure them more clearly. This in turn has facilitated communication with partners in the health network and from other sectors, who were able to make a significant contribution in defining the DRSP’s service offer. As a result, the DRSP’s action plan is more aligned with their expectations and the needs of the populations they serve, leading to greater synergy in improving the health of Montrealers.

Still, work must carry on to make the most of the typology. Use of a common terminology and of a framework that explains the nature of public health’s work and activities should allow for continuously questioning what is being done, its meaning and its usefulness, thus insuring the relevance of services offered. It also constitutes a promising tool to better communicate and showcase the specific contribution of public health to the population, partners and decision-makers, hence protecting and improving its capacity for action.

Last, with more clearly defined interventions and targets, public health teams are also in a better position to evaluate the outcomes of their work and to identify key improvements for subsequent planning cycles, for the well-being of the population they serve.

Conclusion

More attention and recognition need to be brought to public health. Very few people are familiar with everything it does, sometimes not even the responsible political decision-makers. This situation poses a threat to the survival of its prevention mission. In addition to making it easier for public health actors to adopt a common terminology, the typology of public health interventions is an innovative tool that they can use to better inform the public and decision-makers of the nature of their work. Not only can this help clarify what exactly public health does, it also enhances the latter’s visibility and standpoint.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 34 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the many people at Montréal’s public health department who have contributed directly or indirectly to the development and improvement of the typology. Special thanks to Dr. Ak’Ingabe Guyon and Dr. Richard Lessard for their enthusiastic review of the first manuscript and their many useful suggestions.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The Health Policy Reference Center, SocINDEX, CINAHL, Evidence-Based Medicine Reviews, Medline and Embase databases were consulted, and a Web search was performed between October 13 and 17, 2017, to identify documents published in English and French since the year 2000. The following key words were used: classification, public health practice, public health function, public health intervention, public health activity.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal . Garder notre monde en santé. Montréal: Direction de santé publique de l’Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal; 2011. Plan régional de santé publique 2010-2015. [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia, Ministry of Health. (2017). Promote, protect, prevent: our health begins here [electronic resource]: BC’s Guiding Framework for Public Health, www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2017/BC-guiding-framework-for-public-health-2017-update.pdf.

- Direction régionale de santé publique, Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux du Centre-Sud-de-l’Île-de-Montréal (CCSMTL) Offre de services détaillée. Montréal: Direction régionale de santé publique.; 2017. Plan d’action régional intégré de santé publique de Montréal 2016-2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon F, Bergeron P, Fortin J-P. Le champ contemporain de la santé publique. In: Bégin C, Bergeron P, Forest P-G, Lemieux V, editors. Le système de santé québécois. Un modèle en transformation. Montréal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal; 1999. pp. 229–258. [Google Scholar]

- Gouvernement du Québec . Pour améliorer la santé de la population du Québec : Le Programme national de santé publique 2015-2025. Québec: Direction des communications du ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guyon A, Perreault R. Public health systems under attack in Canada: evidence on public health system performance challenges arbitrary reform. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2016;107(3):e326–e329. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.107.5273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada . Learning from SARS: renewal of public health in Canada – report of the National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm, L., Gruszin, S., & Churches, T. (2009). A multidimensional classification of public health activity in Australia. Aust New Zealand Health Policy. 10.1186/1743-8462-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Régie régionale de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal . La prévention en actions. Plan d’action montréalais en santé publique 2003-2006. Montréal: Direction de santé publique de la Régie régionale de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Turnock BJ, Handler AS, Miller CA. Core function-related local public health practice effectiveness. J Public Health Manag Pract. 1998;4(5):26–32. doi: 10.1097/00124784-199809000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Federation of Public Health Associations, A Global Charter for the Public’s Health—the public health system: role, functions, competencies and education requirements, The European Journal of Public Health Advance Access published March 8, 2016, https://www.wfpha.org/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 34 kb)