Abstract

Leishmania, an obligate intracellular parasite is eliminated by a strong Th-1 host response. As Vitamin D metabolism and its receptor activity are important factors in human native immune system against some microorganisms, we hypothesized that VDR gene polymorphisms and concentration of Vitamin D might have effect on incidence of cutaneous leishmaniasis. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between VDR gene polymorphism and/or the serum vitamin D level and leishmaniasis in the infected patients in comparison to the healthy individuals. In this case–control study, the BsmI, FokI and Taq1 polymorphisms in the VDR gene and serum levels of vitamin D were studied in Iranian infected with Leishmania tropica (n = 50) and healthy controls using polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP) and Electrochemiluminescence methods respectively. Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS software, Chi square and ANOVA tests. The results of this study showed that despite the relatively higher frequency of BsmI-BB, FokI-FF and TaqI-Tt than Non BsmI-BB, Non FokI-FF and Non TaqI-Tt in the patients compared with the healthy individuals, the differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Based on our findings, the relationship between the VDR polymorphism, the serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and the susceptibility to Leishmania tropica infection, remains unclear requiring further in-depth studies. However, for better interpretation, it is necessary to consider factors such as the size of the sample examined and the other alleles of VDR, including ApaI.

Keywords: Cutaneous leishmaniasis, VDR polymorphism, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, L. tropica, Iran

Introduction

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL) is a protozoan parasitic disease common in 98 countries, including Iran. In Iran, two species of Leishmania, Leishmania tropica and Leishmania major are known as causative agents of the diseases. Clinical manifestations are diverse and can sometimes be problematic or in abnormal forms. In addition, the incubation period, the number and severity of the lesions or clinical progression of the disease can vary widely among people (Sharifi et al. 2015). Leishmania tropica is responsible for creating lupoid and non-curable forms of cutaneous leishmaniasis in many countries, including Iran. It also has a special clinical significance in terms of relapse. Innate and adaptive immunity, most importantly macrophages and T cells, play significant role in host’s responses against intracellular microorganisms, including leishmania, which is an obligate intracellular parasite of the macrophages. The best response to leishman bodies occurs via the actions of the Th1 cells and their lymphokines (Ehrchen et al. 2007; Whitcomb et al. 2012). Recently, the results of some studies have revealed that the active form of vitamin D selectively changes some of the key functions of interferon gamma-activated macrophages (Helming et al. 2005). The 1,25D3 molecule is a steroid hormone that interferes with a wide range of cellular activities, such as differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis (Cutolo et al. 2014). This vitamin, in its active form, is an important regulator of the immune system and plays a significant role in the maturity of dendritic cells, and the modulation of T helper cells as well as the differentiation of leukocytes. The effects of active form of vitamin D is achieved through binding to its receptor, the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which is expressed in the nucleus of various types of cells, including immune cells (Ramos-Martínez et al. 2013). Although, the role of this vitamin in preventing a group of diseases is not fully understood, the symptoms of autoimmune diseases due to Th1 cells defects can be reduced or eliminated by treatment with 1,25D3 (Whitcomb et al. 2012). Many polymorphisms have been identified in different regions of the VDR gene. In fact, these polymorphisms can be identified based on the location of the digestive enzyme identified in the polymerase chain reaction–restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP) method and they show specific genotypes. Given the existence of polymorphism in this gene, it is likely that different polymorphisms, alone or in combination, can alter the function of the VDR and for instance, regulate the immune response (Uitterlinden et al. 2004). It should be noted that the susceptibility of people to infectious diseases can change with respect to factors such as the state of immunity and genetic constituents of the individuals. That’s why one might even has an asymptomatic infection if challenged with a virulent strain. The human VDR gene is located on chromosome 12, which has 8 coding and 3 non-coding regions (Santoro et al. 2015). The most studied VDR gene polymorphisms in the various diseases were ApaI, BsmI, TaqI and FokI (Rashedi et al. 2014). Their polymorphisms were determined using the specific restriction enzyme, for example, TaqI polymorphism was defined with the TaqI digestive enzyme and according to its cut-off location, TT (absence of enzyme identification), Tt (heterozygous enzyme detection site), and tt (presence of detectable enzyme position)can be identified respectively (Abbasi et al. 2010). It appears that the changed VDR may lose its ability to bind the vitamin D, and also its effects in supporting the macrophages to inhibit the growth of intracellular microorganisms (Shang et al. 2012). In addition, the suppressive role of the vitamin D were evaluated in trial studies on some autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune encephalomyelitis, type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus, tuberculosis, osteoporosis, leprosy, hepatitis B and many types of cancer, and showed that supplementation of the vitamin could prevent or reduce clinical signs in these patients (Dankers et al. 2017; La Marra et al. 2017; Mandal et al. 2015; Panwar et al. 2016; Yao et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2018). It has also been revealed that the deficiency of 1,25D3 during pregnancy or early life increases the severity of asthma in adulthood (Shao et al. 2012).

A study on the TaqI gene polymorphism in VDR in patients with leprosy showed that in tt homozygous individuals, the vitamin D receptor switched immune response to Th1 whereas, TT homozygotes produced Th2 responses. As well, in one case of pulmonary tuberculosis, homozygous tt has also been implicated in the development of resistance to the disease. These data suggest that the VDR genotype may affect the Th1–Th2 pattern of immune response in tuberculosis and many infectious or autoimmune diseases (Roth et al. 2004). However, the role of vitamin D and its receptor function is not completely clear in protozoan infections. There are few studies about the role of this vitamin receptor or lack of the dietary vitamin on the immune response to cutaneous leishmaniasis and the inconsistent results were obtained. In a murine model study involving two susceptible (BALB/c) and resistant (C57BL/6) mice to Leishmania infection, the results have shown that lack of vitamin D receptor or vitamin D deficiency (ligand) in several ways can increased host resistance to L. major infection only if the host has necessary conditions for the development of type Th1 response. In C57BL/6 mice, vdr-ko, there were fewer lesions than wild-type C57BL/6 mice. Thus, this phenotype was not observed in vdr-ko mice with the BALB/c background (Whitcomb et al. 2012). In another study of L. major infection in vdr-ko mice, the vdr gene was manipulated, these mice were more resistant than wild-type control animals. Because in the group of interferon gamma-producing mice, T cells produced an effective Th1 response and macrophages were able to remove the parasite (Ehrchen et al. 2007). Therefore, given the important role of vitamin D receptor on the activity of this vitamin, it is hypothesized that the genetic variation in the gene of this receptor can lead to a Th1/Th2 balance towards Th1 lane, thereby leading to increased resistance to L. major infection. In one more study, the only active form of this vitamin in BALB/c mice infected with leishmania major compared to the control group. It was observed that the pro-inflammatory cytokines production in infected mice with vitamin-treated parasites was lower than control group without the treatment, while there was no difference in the number of parasites in both case and control groups (Whitcomb et al. 2012). Using mouse model, VDR-dependent anti-parasitic activity in macrophages infected with L. major was inhibited after treatment with 1,25D3 (Ehrchen et al. 2007). Alternatively, BALB/c mice infected with L. Mexicana and then treated with vitamin D have shown recovery process more than the control group that did not receive the vitamin.

There are few studies provide evidence about the role of vitamin D and VDR in leishmaniasis. Although, they worked on experimental models and showed controversial outcomes due to using the various experimental models or the species of the parasite. In spite of the importance of L. tropica as the cause of cutaneous or visceral leishmaniasis, it has no convenient animals models. It leads to missing numerous important information about the development and the pathology of the disease (Ehrchen et al. 2007; Ramos-Martínez et al. 2013; Whitcomb et al. 2012).

In the case of L. tropica, the effect of this vitamin concentration as well as host VDR gene polymorphisms of the parasite has not been investigated in Iran. For this reason, we aimed to study polymorphisms or variety of vitamin D receptor gene alleles and serum levels of this vitamin measured in patients with Leishmania tropica infection and healthy people in Kerman province, Iran.

Materials and methods

This study was case-control. In this project, 50 positive cutaneous leishmaniasis patients were selected as the cases from people referred to an exceptional leishmaniasis laboratory. Also, 50 healthy people with any relation with cases were selected as the control group during the summer of 2014 and all subjects were examined. Inclusion criteria were:

Control group

Includes people who do not have any clinical signs of active or passive leishmaniasis, between 6 and 60 years old and having a relationship with the patient.

Case or patient group

Individuals aged 6–60 years, already confirmed by positive microscopic exam and have active ulcers in the previous year. Given the significant role of several factors including life style, genetic and diet that have effect on the vitamin level we selected family members of the cases with similar situation with them as a control group.

Exclusion criteria in both groups: individuals having any background illness such as diabetes, cancer, congenital diseases, allergies, age less than 5 and more than 60 years old, positive history of anticonvulsive medications such as phenobarbital or vitamin D supplements that affect the metabolism of this vitamin. SPSS software version 20 was used to analyze the data and the significance level was considered less than 0.05. After completing the consent form and a questionnaire on demographic information, clinical signs and information about lesions, such as size and number of the wound, a cutaneous lesion of the patients was sampled. After sterilizing the lesion with 70% alcohol, the lesion was scraped and 2 samples were prepared from the surrounding tissue around the lesion. After drying, the slides were fixed with methanol. Also, from each subject in the two study groups, 5 ml blood of sample in a vial containing anticoagulant (EDTA) was taken and transferred in a cold chain to the parasitology lab of the Kerman Medical School. The skin specimens were stained using Giemsa and finally examined by light microscope. If leishman bodies, were found, the sample was considered as a positive case. The diagnosis at species level was done by PCR method using specific primers (Medzhitov 2008). Moreover, the plasma was separated from each blood sample by centrifugation at 2500 rpm for 10 min, then subdivided into vials for measuring the vitamin D level using the Elecsys device and the luminescence electrode test. The vials were kept in a freezer at − 20 °C until the time of the tests. The measurements using Roche Elecsys Vitamin D Total kits were done according to the manufacturer’s procedure. Levels of Vitamin D was interpreted as follow: level of vitamin < 20 ng/mL (deficiency), 20 to < 30 ng/mL (insufficiency) and level of ≥ 30 ng/mL (vitamin D sufficiency).

Isolation of white blood cells from the blood

After separating the plasma, the blood sediment in the vials was stored in a freezer − 20 °C until extraction of the DNA for molecular testing. Briefly, 500 μL of each blood sample was poured into two 15 ml flask tubes, then 8 ml of the RBC lysis buffer (3.8 g NH4Cl, 1 g KHCO3, 0.37 g EDTA/1 L H20, and pH 7.4) added to each tube and placed at 37° C for 10 min. After adding 2 ml of PBS buffer to each tube they were centrifuged for 25 min at 3000 rpm. The supernatant of the tube was empty and again, 1 mL of RBC lysis buffer was added to the precipitate inside the tubes. After 10 min of incubation at 37° C in Ben-Mari, 500 μL of PBS buffer was added. They were centrifuged at 8000 g for 2 min. After discarding the supernatant, the WBCs containing washed sediment were transferred to labeled micro tubes. The cells were kept at − 20 °C in a freezer for molecular testing.

DNA extraction from the blood sample

First, the freezed WBC cells were thawed at 37 °C and the tubes were then centrifuged for 1 min at 13,000g. The DNA extraction was performed using the GeneAll kit made in Korea according to instructions of the manufactures. Samples were examined for quantitative DNA analysis by NanoDrop (make and city of manufacture), at a ratio of 260/280 OD. The DNA was kept at − 20 °C until PCR examination.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

This assay was based on the amplification of the BsmI, TaqI and FokI loci of human leucocytes. Specific primers BsmI (ERO961), TaqI (ERO671) and FokI (ERO871) were prepared according to the Rathored et al. (2012). PCR mix consisted 10 × PCR buffer, 1.25 mM dNTPs, 2.5U of Taq polymerase, 20–30 ng of DNA template and 10 pmol of each primer in a final volume of 25 μL.

PCR amplifications were performed with 35 cycles of denaturation (94 °C, 20 s), annealing (62 °C, 40 s), extension (72 °C, 1 min) and denaturation (94 °C, 30 s), annealing (68 °C, 30 s) and extension (72 °C, 30 s) and denaturation (94 °C, 30 s), annealing (60 °C, 30 s), extension (72 °C, 30 s) for BsmI, TaqI and FokI loci respectively.

Electrophoresis

The PCR products were identified on 1, 1 and 1.5% agarose gels for TaqI, BsmI and FokI fragments respectively.

RFLP assay

Diagnostic fragments using BsmI enzyme were: 822; 822, 650, 172 and 650, 172 bp for BB, Bb and bb genotypes respectively. The fragments of 265; 265,196, 69 and 196, 69 bp were specific for FF, Ff and ff genotypes using FokI enzyme and diagnostic fragments using TaqI enzyme were: 456; 456, 293, 161 and 293, 161 bp for TT, Tt and tt genotypes respectively. The polymorphism were identified using 3% agarose gel and Thermo Sientific O’GeneRuler DNA Ladder (100 bp and Low range for both BmsI and TaqI and also FokI respectively).

Results

Out of 100 individuals involved in this study, 45 (45%) and 55 (55%) were males and females respectively. However, out of 50 patients with CL, 23 (46%) were males and 27 (54%) were females also, of 50 healthy controls, 22 (44%) were males and 28 (56%) were females. Out of 50 couples with any relationship, 12 couples (24%) were wife and husbands, 11 couples (22%), mother and daughter, 13 couples (26%), mother and son, 4 couples (8%), father and daughter, 4 couples 8%) father and son, 2 couples (4%), siblings, 3 couples (6%) brothers and brothers, 1 couples (2%) were sisters and sisters.

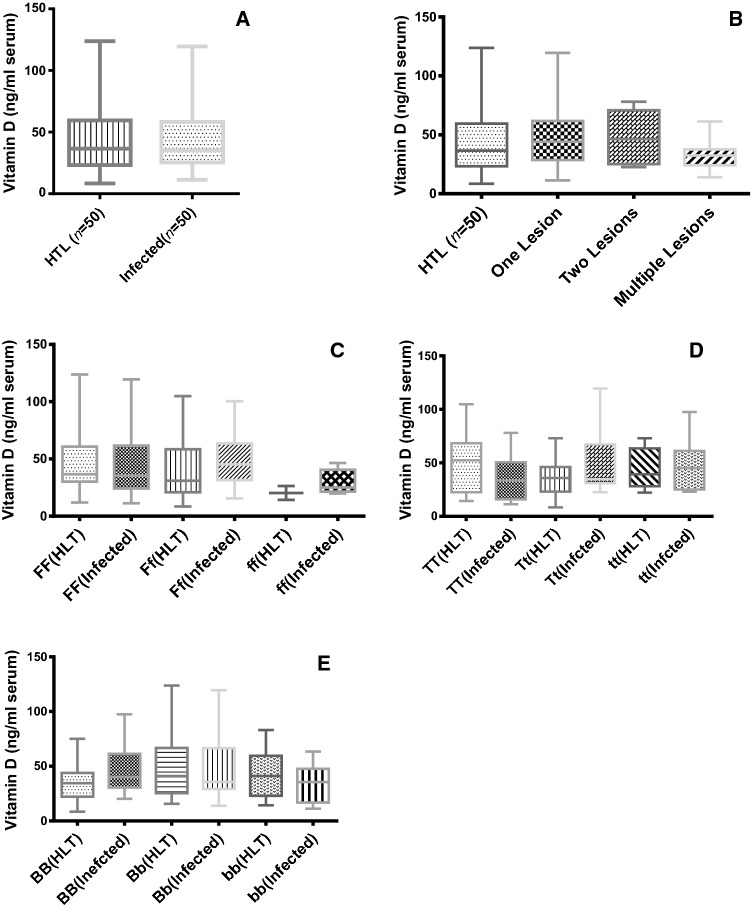

The results showed that although the serum concentration of this vitamin among patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis was relatively lower than in the control group, this difference was not significant between the two groups. Consequently, there was no significant relationship between serum level of vitamin D3 and susceptibility to leishmaniasis and the number of lesions (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Vitamin D level (ng/ml serum) in ACL leishmaniasis patients and healthy individuals measured by the Elecsys device and the luminescence electrode test in human subjects with ACL (n = 50) as well as in healthy controls (n = 50). Serum levels of Vitamin D in Healthy and ACL infected patients (a); number of lesions in patients (b); different alleles of FokI (c); different alleles of TaqI (d) and different alleles of BsmI (e) were detected using PCR–RFLP

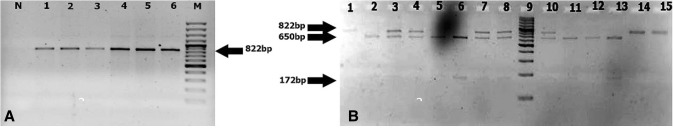

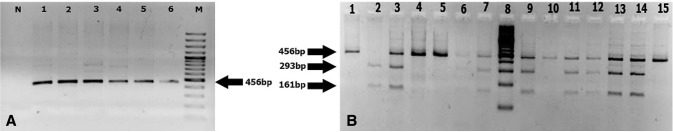

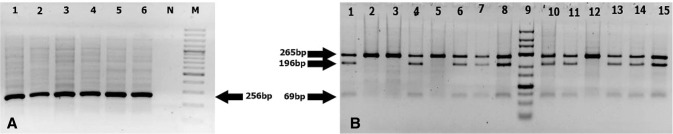

The PCR products digested with the BsmI enzyme showed genotypes BB (822 bp), Bb (822, 650, 172 bp) and bb (650, 172 bp). The results of the TaqI enzyme after cutting the PCR product were: TT (456 bp), Tt (456, 293, 161 bp) and tt (293, 161 bp). While the PCR product after the enzyme digestion with the FokI enzyme indicated FF (265 bp), Ff (265, 196, 69 bp) and ff (196, 69 bp) genotypes (Figs. 2, 3, 4).

Fig. 2.

a 1% Agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR amplification of an 822-bp of the BsmI gene. Lane 1: negative control (no DNA); 2–7: patient’s samples and 8: DNA ladder 100 bp. b Digestion of PCR product targeting the BsmI gene using BsmI enzyme on 3% gel agarose to distinguish polymorphism BB (822 bp), Bb (822, 650, 172 bp) and bb (650, 172 bp) alleles. Lanes 1–8 sample patients, Lane 9 DNA ladder (100 bp), and lanes 10–15 sample patients

Fig. 3.

a 1% Agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR amplification of a 456-bp of the TaqI gene. Lane 1: negative control (no DNA); 2–7: patient’s samples and 8: DNA ladder 100 bp. b Digestion of PCR product targeting the TaqI gene using TaqI enzyme on 3% gel agarose to distinguish polymorphism TT (456 bp), Tt (456, 293, 161 bp) and tt (293, 161 bp) alleles. Lanes 1–7 and 9–15: sample patients, Lane 8 DNA ladder (100 bp)

Fig. 4.

a 1.5% Agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR amplification of a 265-bp of the FokI gene. Lane 1–6: patient’s samples; 7: negative control (no DNA) and 8: DNA ladder 100 bp. b Digestion of PCR product targeting the FokI gene using FokI enzyme on 3% gel agarose to distinguish polymorphism FF (265 bp), Ff (265, 196, 69 bp) and ff (196, 69 bp) alleles. Lanes 1–8 and 10–15: sample patients, Lane 9 DNA ladder (25–700 bp, low range DNA ladder)

Frequency of all genotypes of VDR gene and serum concentrations of vitamin D were not significantly correlated. In addition, the results of this study showed that there was relatively higher frequency of BsmI-BB than Non-BsmI-BB in the patients group compared to healthy subjects, but no significant differences were observed between the case and control groups in relation to genotypes diversity of BsmI gene and the susceptibility to Leishmania tropica infection.

Moreover, the results this study showed that despite the relatively higher frequency of TaqI-Tt genotype than non-TaqI-Tt in the case group, there was no significant difference in the susceptibility of Leishmania tropica infection between the two groups. As well, the data of this study revealed that even with the relatively higher frequency of FokI-FF genotype than non-FokI-FF in the patients, the genotype differences and the susceptibility to L. tropica infection was not significantly altered between both groups.

Discussion

Leishmania, easily enters into hosts, rapidly enters hosts’ macrophages, intelligently expands by phagocytosis through complement receptors and escapes from the danger environment. It has been shown that a Th1 or Th2 response predominates against the pathogen (Gupta et al. 2013; Sun 2010). It is worth mentioning that although the immune response is necessary for the parasite removal, some immune responses, such as inflammation, can, in some cases, be the main cause of leishmanial lesions.

Perhaps this is why lesions are not wounded in people with AIDS or lupoid form. Acute inflammation is considered as a major strategy for wound healing because inflammation is one of the host responses to pathogenic invasions. However, if the acute responses fail to eliminate the pathogen, the process becomes chronic. This process is naturally controlled by the host, but sometimes it can be insuppressible and pathologic (Medzhitov 2008). Recently, the role of vitamin D on inflammation and regulation of the immune system, especially innate immunity, has been shown in several studies. However, the mechanism has not been clearly proven. An innate immune response strongly depends on the endocrine system of vitamin D that balances the inflammation (Jones 2008). In addition, the results of some studies suggest that the active form of vitamin D selectively inhibits some of the key functions of interferon-gamma-activated macrophage. The outcome of vitamin D on the immune system is one of its most important roles. This vitamin, by binding to its receptor, Vitamin D receptor (VDR), regulates the immune system in various immune cells, especially antigen presenting cells such as dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages (White 2008). Undoubtedly, VDR is crucial for all known effects of vitamin D. The taking part of Vitamin D/VDR in anti-inflammatory activity has been shown in many infections (Sun 2010).

Interestingly, some microorganisms can modify the path of the Vitamin D/VDR signal, which is one of the pathogens’ response against host’s defense mechanism. For example, Mycobacterium tuberculosis diminishes the innate immune response by decreasing the expression of the VDR. It has also been seen that Mycobacterium leprae disturbs vitamin D-dependent immunosuppression by inhibiting VDR activity (Liu et al. 2012). Reducing or malfunctioning the activity of VDR activity to express the elements of the innate immune function allows the survival of intracellular bacteria into the cytoplasm of nucleated cells and consequently, chronic infection and inflammation are observed (Wu and Sun 2011). Moreover, the results of some studies have revealed that with the removal of pathogens, the disorder in the regulation of vitamin D metabolism was also improved and the signs of inflammation were recovered. Laboratory studies have shown that the active form of vitamin D increases the ability of macrophages to inhibit the growth of intracellular microorganisms by increasing the binding of phagosome with lysosome, as well as stimulating synthesis of nitric oxide free radicals (Rezende et al. 2007; Van Etten et al. 2003). However, it seems that the mechanism of immune responses to these intracellular organisms, including parasites, is much more complicated. It is therefore placed that, the serum levels of this vitamin, and on the other hand, the proper activity of its nuclear receptor in the macrophages play important roles in innate immune system and are discussed in terms of susceptibility and resistance of the host to/against microorganisms (Rashedi et al. 2014). The role of the VDR gene polymorphism has been investigated in various infectious and non-infectious inflammatory diseases at different nationality and various contradictory results were obtained (Fukazawa et al. 1999). As expected, the nucleotide sequence of the VDR encoding gene shall be different among different individuals (Rashedi et al. 2014). In parasitic infections such as leishmaniasis, factors such as parasite and host genetics as well as environment are important in resistance/susceptibility of the disease (Baldwin et al. 2007). Leishmaniasis studies have been limited to experimental models infected with L. major and L. mexicana. It was revealed that following treatment of macrophage infected with L. major using active vitamin D, the VDR-dependent killing activity of the macrophages was inhibited. In other words, vitamin D could suppress the key function of activated macrophages in invitro (Ehrchen et al. 2007). Regarding the role of VDR or deficiency of the vitamin in the diet, a study was conducted on the immune response to cutaneous leishmaniasis in two susceptible (BALB/c) and resistant (C57BL/6) strains to Leishmania major. The researchers observed fewer lesions with smaller sizes in mice with the background of C57BL/6 and vdr-ko (whose VDR gene was manipulated) compared with wild types (Whitcomb et al. 2012). In the animal, an effective Th1 response was produced via production of interferon gamma by T cells. Consequently, APCs managed to remove the leishmania in the host as well as to reduce the parasitic burden and also limit the lesion size (Ehrchen et al. 2007). As well, since vitamin D regulates these effects through its receptor, it was hypothesized that the defect of the receptor could alter the Th1/Th2 balance towards Th-1 and increase the resistance to Leishmania major infection. Nevertheless, this phenomenon was not observed in vdr-ko mice with the BALB/c background. Also, the deficiency of vitamin D in the diet of wild mice of C57BL/6, did not reduce the severity of lesions (Whitcomb et al. 2012). It can be concluded that the disruption of the VDR function or the removal of its ligand, 1.25D3, can increase the resistance to Leishmania major infection if the background and necessary conditions for developing a Th1-type immune response are provided in the host (Whitcomb et al. 2012). In contrast, other studies have shown that neither the genetic loss of the VDR nor the exclusion of vitamin D in the diet of BALB/c mice did change the susceptibility of L. major infection. Susceptibility of wild-type mice might be related to their inability to produce a Th1 response against the parasite and the effect of vitamin D receptors may depend on the nature of the host immune response. Therefore, other phenomena such as genetic mechanisms can play a role in resistance to leishmaniasis. That’s why, further identification of the role of Vitamin D/VDR can help to clarify the pathogenesis of a range of human diseases, including leishmaniasis, and to design new methods for prevention and treatment (Sun 2010; Whitcomb et al. 2012). In L. tropica infection, the association between serum vitamin D level and the polymorphism of the VDR gene as well as regulatory effects of this vitamin on immune responses to the disease is not identified yet. Hence, the polymorphism of the vitamin D receptor gene and the vitamin levels in L. tropica infected-patients were investigated.

Levels of the vitamin in sera less than 50 nmol/L or 20 ng/mL have established as vitamin D deficiency (Holick et al. 2011). A systematic review and meta-analysis study showed that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the Iranian people is 0.54. It means more than half of them suffer from vitamin D deficiency and the age group 20–50 years has the highest deficiency rate (0.72) (Vatandost et al. 2018). However, other studies have been reported the prevalence between and 0.16 to 0.85(Kelishadi et al. 2016; Rahnavard et al. 2010). Our results also showed that the serum vitamin D level in patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis was lower than in healthy group, nevertheless there was no significant difference between both groups (P value > 0.05). It should be noted that given this fact that vitamin D3 deficiency is common among Iranian people, this can be a reason for the absence of significant differences between the two study groups. Each of factors such as person’s clothing or skin type, nutritional factors, race, and environmental factors including the location, design of buildings and exposure to sunlight may play role in determining the amount of vitamin D intake or having an active form of the vitamin. On the other hand, a person can get adequate intake but if does not have enough exposure to sunlight, vitamin D may not be effective. Another important factor in the proper functioning of the Vitamin D/VDR complex is the quality of the vitamin D receptor, in which, if there are any defects, absorption of the active form of vitamin D in the cells would be poor. One way of detecting the quality of the vitamin D receptor can be by examining its gene polymorphism. Our results showed that despite the relatively higher frequency of BsmI-BB than Non BsmI-BB among the patients in comparison to the healthy subjects, the difference in BsmI genotypes and the susceptibility to L. tropica infection was not significantly different in two groups. Likewise, the results of a meta-analysis study suggested that there was no association between the risk of osteoporosis and kidney cancer and the polymorphism of the VDR gene in the BsmI genotype, in the whole of the white and Asian populations (Qin et al. 2013). Whereas, there are some evidences that the BsmI polymorphism was associated with the risk of several types of cancer. Moreover, different results have been reported in a study on the relationship between BsmI polymorphism and lupus nephritis (Huang et al. 2002). As well, a study on the relationship between VDR gene polymorphisms (BsmI) and the risk of diabetes mellitus has also been conducted. In the whole population studied, the Asian and Latin, bb genotype was associated with this type of diabetes, but no allele B and genotype BB were associated. Of course, as only few studies have been included in the meta-analysis study, these results should be interpreted more cautiously and more studies are needed to accomplish these goals in the future. Additionally, in the present study, the association between FokI polymorphism and susceptibility to Leishmaniasis was not observed. While, its association with cardiovascular disease in French diabetic patients was reported and the deficiency of vitamin D was significantly lower in individuals with F allele in FokI polymorphism (Ortlepp et al. 2001). Furthermore, the results of our study showed that despite the relatively higher frequency of TaqI-Tt genotype than the non TaqI-Tt among the diseased, the different genotypes of TaqI in both groups showed no significant difference in susceptibility to Leishmaniasis. interestingly, this association between genetic diversity of TaqI and leprosy and multiple sclerosis has been observed so that TaqI-tt homozygotes could switch the immune response to Th1 (Köstner et al. 2009; Tajouri et al. 2005). In addition, a study conducted in India (Bhanushali et al. 2009) showed that vitamin D levels in the serum of individuals with TaqI-tt genotype were higher than non-TaqI-tt subjects and these individuals were more resistant to tuberculosis. Therefore, studying the serum level of vitamin D associated with the related gene polymorphism can help us to generate more accurate results (Rashedi et al. 2014).

In summary, the results of this study showed that probably the serum level of vitamin D3, as well as the polymorphisms in the or genotypes of vitamin D receptor, did not affect the susceptibility to cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L. tropica. But for more accurate interpretation, more research is needed on a larger scale and in different ethnic groups. In addition, other forms of polymorphisms and other important factors in genotypes of the VDR gene, including ApaI or secretion of some chemokines are suggested to be measured in these individuals.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Kerman University of Medical Sciences Vice Chancellor for Research to ZB, under contract 93/60. We thank patients and healthy volunteers who participated in this study. We are appreciative to personnel of Dadbin center, Alireza Kayhani for their technical assistance.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: ZB, ISh. Collecting samples and preparing for experiment: HSh, GSh and ESD. Analysis and interpretation of data: ZB, AA. Drafting of the manuscript: ZB, HSh, OR, MG. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: ZB, ISh, ES, MAM, MG, OR. Statistical analysis: AA.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors and coauthors declare that they have no conflict of interest that affects this study.

Ethical statement

The study procedures were approved by the joint Ethical Committees of Kerman University of Medical Sciences ethic no. ir.kmu.rec.1393.276. This study was performed in cooperation with Dadbin Clinic’s staff in Kerman, Iran. Initially, the authors coordinated with the health authorities. In addition, the cases with cutaneous leishmaniasis were referred to specialist physicians for free treatment.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. Informed consent forms were signed by the patients or their parents and the data has been kept confidential.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abbasi M, Rezaieyazdi Z, Afshari JT, Hatef M, Sahebari M, Saadati N. Lack of association of vitamin D receptor gene BsmI polymorphisms in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1537–1539. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1504-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin T, Sakthianandeswaren A, Curtis JM, Kumar B, Smyth GK, Foote SJ, Handman E. Wound healing response is a major contributor to the severity of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the ear model of infection. Parasite Immunol. 2007;29:501–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2007.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanushali AA, Lajpal N, Kulkarni SS, Chavan SS, Bagadi SS, Das BR. Frequency of fokI and taqI polymorphism of vitamin D receptor gene in Indian population and its association with 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. Indian J Hum Genet. 2009;15:108. doi: 10.4103/0971-6866.60186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutolo M, Paolino S, Sulli A, Smith V, Pizzorni C, Seriolo B. Vitamin D, steroid hormones, and autoimmunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1317:39–46. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dankers W, Colin EM, van Hamburg JP, Lubberts E. Vitamin D in autoimmunity: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Front Immunol. 2017;7:697. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrchen J, et al. Vitamin D receptor signaling contributes to susceptibility to infection with Leishmania major. FASEB J. 2007;21:3208–3218. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7261com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukazawa T, Yabe I, Kikuchi S, Sasaki H, Hamada T, Miyasaka K, Tashiro K. Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism with multiple sclerosis in Japanese. J Neurol Sci. 1999;166:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta G, Oghumu S, Satoskar AR. Mechanisms of immune evasion in leishmaniasis. In: Sariaslani S, Gadd GM, editors. Advances in applied microbiology. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2013. pp. 155–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helming L, et al. 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a potent suppressor of interferon γ–mediated macrophage activation. Blood. 2005;106:4351–4358. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick MF, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911–1930. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Wu M, Wu J, Tsai F. Association of vitamin D receptor gene BsmI polymorphisms in Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2002;11:31–34. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu143oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin D toxicity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:582S–586S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.582S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelishadi R, Qorbani M, Motlagh ME, Heshmat R, Poursafa P, Bahreynian M. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency according to climate conditions among a nationally representative sample of Iranian adolescents: the CASPIAN-III study. Int J Pediatr. 2016;4:1903–1910. [Google Scholar]

- Köstner K, Denzer N, Mueller CS, Klein R, Tilgen W, Reichrath J. The relevance of vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene polymorphisms for cancer: a review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3511–3536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Marra F, Stinco G, Buligan C, Chiriacò G, Serraino D, Di Loreto C, Cauci S. Immunohistochemical evaluation of vitamin D receptor (VDR) expression in cutaneous melanoma tissues and four VDR gene polymorphisms. Cancer Biol Med. 2017;14:162. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2017.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PT, et al. MicroRNA-21 targets the vitamin D-dependent antimicrobial pathway in leprosy. Nat Med. 2012;18:267. doi: 10.1038/nm.2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal D, Reja A, Biswas N, Bhattacharyya P, Patra P, Bhattacharya B. Vitamin D receptor expression levels determine the severity and complexity of disease progression among leprosy reaction patients. New Microbes New Infect. 2015;6:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:428. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortlepp J, Hoffmann R, Ohme F, Lauscher J, Bleckmann F, Hanrath P. The vitamin D receptor genotype predisposes to the development of calcific aortic valve stenosis. Heart. 2001;85:635–638. doi: 10.1136/heart.85.6.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panwar A, et al. 25-hydroxy vitamin D, vitamin D receptor and toll-like receptor 2 polymorphisms in spinal tuberculosis: a case–control study. Medicine. 2016;95:3418. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin G, Dong Z, Zeng P, Liu M, Liao X. Association of vitamin D receptor BsmI gene polymorphism with risk of osteoporosis: a meta-analysis of 41 studies. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40:497–506. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahnavard Z, Eybpoosh S, Homami MR, Meybodi HA, Azemati B, Heshmat R, Larijani B. Vitamin D deficiency in healthy male population: results of the Iranian multi-center osteoporosis study. Iran J Public Health. 2010;39:45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Martínez E, Villaseñor-Cardoso M, López-Vancell M, García-Vázquez F, Pérez-Torres A, Salaiza-Suazo N, Pérez-Tamayo R. Effect of 1, 25 (OH) 2D3 on BALB/c mice infected with Leishmania mexicana. Exp Parasitol. 2013;134:413–421. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashedi J, Asgharzadeh M, Moaddab SR, Sahebi L, Khalili M, Mazani M, Abdolalizadeh J. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism and vitamin D plasma concentration: correlation with susceptibility to tuberculosis. Adv Pharm Bull. 2014;4:607. doi: 10.5681/apb.2014.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathored J, et al. Risk and outcome of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and serum 25 (OH) D. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:1522–1528. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezende VB, Barbosa F, Jr, Montenegro MF, Sandrim VC, Gerlach RF, Tanus-Santos JE. An interethnic comparison of the distribution of vitamin D receptor genotypes and haplotypes. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;384:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth DE, et al. Association between vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and response to treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:920–927. doi: 10.1086/423212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro D, et al. Vitamin D receptor polymorphism in chronic kidney disease patients with complicated cardiovascular disease. J Renal Nutr. 2015;25:187–193. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang C, Luo P-F, Wei L, Tang W-Q, Cong X-N, Wei P-M. Vitamin D receptor genetic polymorphisms and tuberculosis among Chinese Han ethnic group. Chin Med J. 2012;125:920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao T, Klein P, Grossbard ML. Vitamin D and breast cancer. The Oncologist. 2012;17:36–45. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi I, et al. A comprehensive review of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Kerman province, southeastern Iran-narrative review article. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J. Vitamin D and mucosal immune function. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:591. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32833d4b9f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajouri L, et al. Variation in the vitamin D receptor gene is associated with multiple sclerosis in an Australian population. J Neurogenet. 2005;19:25–38. doi: 10.1080/01677060590949692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uitterlinden AG, Fang Y, van Meurs JB, Pols HA, van Leeuwen JP. Genetics and biology of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms. Gene. 2004;338:143–156. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Etten E, Branisteanu D, Overbergh L, Bouillon R, Verstuyf A, Mathieu C. Combination of a 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 analog and a bisphosphonate prevents experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and preserves bone. Bone. 2003;32:397–404. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatandost S, Jahani M, Afshari A, Amiri MR, Heidarimoghadam R, Mohammadi Y. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Health. 2018;24:269–278. doi: 10.1177/0260106018802968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitcomb JP, et al. The role of vitamin D and vitamin D receptor in immunity to Leishmania major infection. J Parasitol Res. 2012;2012:13. doi: 10.1155/2012/134645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JH. Vitamin D signaling, infectious diseases, and regulation of innate immunity. Infect Immunity. 2008;76:3837–3843. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00353-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Sun J. Vitamin D, vitamin D receptor, and macroautophagy in inflammation and infection. Discov Med. 2011;11:325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Zeng H, Zhang G, Zhou W, Yan Q, Dai L, Wang X. The associated ion between the VDR gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma and the clinicopathological features in subjects infected with HBV. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:953. doi: 10.1155/2013/953974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, et al. Associations between VDR gene polymorphisms and osteoporosis risk and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:981. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18670-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]