Abstract

Background

The interleukin-12/23p40-subunit-inhibitor ustekinumab significantly improved spondylitis-related symptoms through Week 24 in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) patients with peripheral arthritis and physician-reported spondylitis (PA-PRS) in PSUMMIT-1&2. We further evaluated ustekinumab’s effect on spondylitis-related endpoints in PSUMMIT-1&2 tumour necrosis factor-inhibitor (TNFi)-naïve patients with PA-PRS.

Methods

Patients with active PsA (≥5 swollen and ≥5 tender joints, C-reactive-protein ≥ 3.0 mg/L) despite conventional (PSUMMIT-1&2) and/or prior TNFi (PSUMMIT-2) therapy received subcutaneous ustekinumab 45 mg, 90 mg or placebo (Week 0, Week 4, Week 16). Changes in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) neck/back/hip pain question (#2) and modified BASDAI (mBASDAI, excluding PA) scores and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) responses were assessed at Weeks 12 and 24.

Results

The pooled PSUMMIT-1&2, TNFi-naïve (n=747), PA-PRS (n=223) subset (158 with human-leucocyte-antigen (HLA)-B27 results) presented with moderate-to-severe spondylitis-related symptoms (mean BASDAI-neck/back/hip pain-6.51, mBASDAI-6.54, BASDAI-6.51, ASDAS-3.81). Mean Week 24 changes were larger among ustekinumab than placebo-treated patients for both neck/back/hip pain (−1.99 vs −0.18) and mBASDAI (−2.09 vs −0.59). Improvements in neck/back/hip pain and fatigue appeared numerically greater in HLA-B27+ than HLA-B27– patients; those for other domains were generally consistent. Greater proportions of ustekinumab versus placebo-treated patients achieved ASDAS clinically important improvement at Week 24 (decrease ≥ 1.1; 49.6% vs 12.7%; nominal p<0.05).

Conclusions

Improvements in BASDAI neck/back/hip pain and mBASDAI among ustekinumab-treated, TNFi-naïve, PsA patients with PA-PRS were clinically meaningful and consistent across assessment tools. Numerically greater improvements in neck/back/hip pain in HLA-B27+ than HLA-B27– patients, noted in the context of similar overall mBASDAI improvements between the subgroups, suggest ustekinumab may improve disease activity in TNFi-naïve PsA patients likely to exhibit axial disease.

Clinical trial registration numbers

PSUMMIT 1, NCT01009086; PSUMMIT 2, NCT01077362.

Keywords: psoriatic arthritis, axial disease, interleukin-12/23, ustekinumab, HLA-B27

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

In psoriatic arthritis (PsA) patients with baseline peripheral arthritis and physician-reported spondylitis (PA-PRS), ustekinumab significantly improved spondylitis-related symptoms through Week 24 of the PSUMMIT-1&2 trials.

What does this study add?

In tumour necrosis factor-inhibitor (TNFi)-naïve PsA patients with PA-PRS and moderate-to-severe spondylitis-related symptoms at baseline, mean improvements at Week 24 were larger following ustekinumab than placebo for neck/back/hip pain (−1.99 vs −0.18) and modified Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (mBASDAI) (−2.09 vs −0.59). Numerically greater improvements in neck/back/hip pain and fatigue were seen in human-leucocyte-antigen (HLA) HLA-B27+ than HLA-B27– patients; overall mBASDAI improvements were generally consistent between HLA-B27 subgroups.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Ustekinumab may reduce disease activity and thus be an appropriate treatment for TNFi-naive PsA patients with physician-reported signs and symptoms of axial disease.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is one of several spondyloarthritides (SpA), a grouping of diseases with shared common immunological and inflammatory components, but unique clinical manifestations.1 Despite having distinct presentations, consistencies in genetic susceptibility markers and associated aberrations in immune response (including activation of the interleukin (IL)−23/IL-17 axis),2 can result in overlapping clinical phenotypes of SpA. Patients with PsA and ankylosing spondylitis (AS), the archetype for axial SpA, can both present with axial arthritis, peripheral arthritis and enthesitis.3 4 One of the most notable genetic susceptibility markers is expression of the human-leucocyte-antigen B27 allele (HLA-B27) of major histocompatibility class I region.5

PsA patients with axial involvement will typically also have peripheral disease. The prevalence of axial PsA increases with duration of disease, that is, 5%–28% among patients with early-onset versus 25%–70% with long-standing PsA.4 Further, PsA patients with axial disease are more likely to be HLA-B27+ than are those with only peripheral arthritis,3 and HLA-B27 + status predicts earlier development of axial disease.4 Although HLA-B27 + is highly associated with the pathogenesis of AS and is present in the vast majority of these patients,4 6 only 20% of patients with PsA are HLA-B27 +.4

While it is known that axial disease in PsA may develop later in life than in AS, yields less severe symptoms, and has radiographic features distinct from AS, a universally accepted definition of axial disease in PsA is lacking and currently being researched.4 7 In contrast, the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society’s (ASAS) classification criteria for axial SpA encompass patients both with and without definite radiographic sacroiliitis. Specifically, patients with chronic back pain for >3 months and age at onset <45 years can be classified with axial SpA in the presence of imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis plus ≥1 typical SpA feature, or in the presence of HLA-B27 plus ≥2 other SpA features.8

Ustekinumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody with high affinity for the p40-subunit shared by IL-12 and IL-23. Ustekinumab demonstrated efficacy in treating multiple domains of PsA, including peripheral arthritis, enthesitis and dactylitis, and significantly inhibited radiographic progression of joint damage in the PSUMMIT-1&2 phase 3 studies.9–11 In these studies, approximately 30% of tumour necrosis factor-inhibitor (TNFi)-naïve and experienced patients in PSUMMIT-1&2 had peripheral arthritis with physician-reported spondylitis (PA-PRS); ustekinumab demonstrated significant improvements in axial signs and symptoms through Week 24 in these patients, regardless of prior TNFi use.12 In contrast, ustekinumab was not effective when evaluated in phase 3 placebo-controlled trials of AS patients,13 which prompted additional post-hoc analyses of the PSUMMIT 1&2 trial data focused on evaluating the efficacy of ustekinumab in treating spondylitis-related signs and symptoms among PA-PRS patients who were naïve to TNFi treatment. Response to ustekinumab was also assessed in patients with or without HLA-B27 expression.

Methods

Patients and study design

As reported previously, the PSUMMIT-1 (NCT01009086)9 and PSUMMIT-2 (NCT01077362)10 studies included adults with active PsA (≥5/66 swollen and ≥5/68 tender joints) despite conventional treatment. While PSUMMIT-1 enrolled only TNFi-naïve patients, PSUMMIT-2 included both TNFi-naïve and TNFi-experienced patients. Patients in both studies randomly received ustekinumab 45 mg, ustekinumab 90 mg or matching placebo at Week 0, Week 4 and Week 16 in a double-blind manner. Stable doses of methotrexate were permitted. Results of post-hoc analyses reported herein derive from response data collected through Week 24. The presence of spondylitis at baseline was based solely on the treating physician’s assessment and did not require radiographic or imaging evidence. The studies were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and International Committee on Harmonisation good clinical practices; both study protocols were approved by each site’s governing ethical body; and all patients provided written informed consent. Separate consent was required for optional genetic testing.

Evaluations

Patients completed the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), a self-assessment tool validated for AS comprising the following six domains: (1) fatigue, (2) total neck/back/hip pain, (3) pain and swelling of peripheral joints, (4) pain at entheseal sites, (5) severity of morning stiffness and (6) duration of morning stiffness.14 Each domain was scored using a visual analogue scale, ranging from 0 (no disease activity) to 10 (maximal disease activity), and individual domain scores were weighted and averaged to yield a total score also ranging from 0 to 10. BASDAI scores ≥4 indicate active disease,15 and patients consider 1-point changes to reflect a minimum clinically important difference in symptoms.16 Given that most PsA patients suffer from polyarticular involvement, with symptoms being more severe—especially in those with axial PsA—than typically experienced by individuals with AS,17 a modified BASDAI (mBASDAI) score, excluding the third domain (pain and swelling of peripheral joints), was employed to focus this study’s assessments on spondylitis-related signs and symptoms. The mBASDAI was calculated as (0.25 [fatigue + total back pain + pain at entheseal sites + 0.5 × DURATION]), with DURATION representing the sum of morning stiffness severity and duration.

The Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score employing C-reactive protein (ASDAS-CRP),18 determined post hoc, is a composite score incorporating BASDAI domains related to total back pain, pain and swelling of peripheral joints and duration of morning stiffness; the patient-reported global assessment of disease activity during the previous week (0=not active, 10=very active); and CRP (mg/L). An ASDAS score <1.3 indicates inactive disease, while decreases ≥2.0 and ≥1.1 indicate major and clinically important improvements, respectively.19–21

Consenting patients from both PSUMMIT studies with adequate samples had DNA extracted from whole blood and genotyped for HLA-B27 using the INNO-LiPA HLA-B Multiplex Plus assay, which is a line probe HLA-typing test based on reverse hybridisation principles (Covance Clinical Laboratory Services, Princeton, NJ, USA). LiRAS software for INNO-LiPA HLA was used to assist with the interpretation of the LiPA results, whereby samples were classified as ‘positive’, ‘negative’ or ‘unable to assign genotype’.

Data analyses

TNFi-naïve patients with PA-PRS from the PSUMMIT studies were included, according to randomised treatment group, in this post-hoc analysis. Mean changes from baseline to Weeks 12 and 24 in total mBASDAI and individual component scores were determined. The proportions of patients achieving ASDAS inactive disease or who experienced major or clinically important improvement from baseline were determined at Weeks 12 and 24. Clinical efficacy endpoints were summarised using descriptive statistics for all TNFi-naïve patients with PA-PRS, as well as in the subset of TNFi-naïve PA-PRS patients whose HLA-B27 status was known. Any statistical testing was performed post hoc and is purely descriptive. As such, the nominal p-values reported should be considered as hypothesis-generating only, with no implication of statistical significance.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

The combined PSUMMIT studies randomised 927 patients. Patient disposition has been previously detailed.9 10 Among 747 TNFi-naïve PsA patients, 223 had PA-PRS. Baseline characteristics were consistent between this subset and the overall study populations,9 10 as well as across randomised treatment groups within the subset (table 1). Among patients with HLA-B27 genotype results, 40 of 158 (25.3%) pooled TNFi-naïve PsA patients with PA-PRS, versus 54 of 327 (16.5%) patients without PA-PRS, were HLA-B27+.

Table 1.

Summary of baseline characteristics for TNFi-naïve PsA patients with PA-PRS. Data presented are n (%) or mean (SD)

| Placebo | Ustekinumab | All | |||

| 45 mg | 90 mg | Combined | Patients | ||

| All patients (N) | 84 | 66 | 73 | 139 | 223 |

| Male | 42 (50.0) | 37 (56.1) | 48 (65.8) | 85 (61.2) | 127 (57.0) |

| Age (years) | 47.01 (12.87) | 45.56 (11.62) | 45.67 (11.66) | 45.62 (11.60) | 46.14 (12.09) |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2) | 28.96 (6.35) | 28.06 (5.16) | 28.69 (5.58) | 28.39 (5.38) | 28.60 (5.76) |

| Duration of disease (years) | |||||

| PsA | 7.11 (8.80) | 6.28 (6.77) | 6.48 (6.36) | 6.39 (6.54) | 6.66 (7.46) |

| Psoriasis | 15.95 (12.82) | 14.58 (10.97) | 16.64 (12.34) | 15.66 (11.71) | 15.77 (12.12) |

| Patient with ≥3% BSA psoriasis | 63 (75.0) | 57 (86.4) | 59 (80.8) | 116 (83.5) | 179 (80.3) |

| PASI score (0–72) | 14.46 (12.53) | 15.11 (13.58) | 13.86 (10.22) | 14.48 (11.95) | 14.47 (12.12) |

| DLQI score (0–30) | 13.13 (8.01) | 12.54 (7.13) | 11.75 (7.08) | 12.14 (7.09) | 12.49 (7.42) |

| Swollen joint count (0–66) | 15.79 (11.02) | 12.76 (7.93) | 12.38 (8.99) | 12.56 (8.48) | 13.78 (9.62) |

| Tender joint count (0–68) | 25.04 (14.85) | 24.33 (15.50) | 21.16 (12.92) | 22.67 (14.24) | 23.56 (14.48) |

| Spondylitis-related activity (0–10) | |||||

| BASDAI total neck/back/hip pain | 6.14 (2.74) | 6.62 (2.31) | 6.84 (2.15) | 6.74 (2.22) | 6.51 (2.44) |

| mBASDAI (excl. peripheral) | 6.27 (1.84) | 6.52 (1.71) | 6.56 (1.63) | 6.54 (1.66) | 6.44 (1.73) |

| BASDAI | 6.37 (1.74) | 6.57 (1.62) | 6.60 (1.60) | 6.59 (1.61) | 6.51 (1.66) |

| ASDAS-CRP | 3.68 (0.88) | 3.86 (0.91) | 3.90 (0.87) | 3.88 (0.89) | 3.81 (0.89) |

| CRP (mg/L) | 18.57 (25.72) | 20.30 (23.19) | 20.63 (20.74) | 20.47 (21.85) | 19.76 (23.35) |

| HAQ-DI score (0–3) | 1.36 (0.63) | 1.33 (0.60) | 1.22 (0.66) | 1.27 (0.63) | 1.30 (0.63) |

| DAS28-CRP | 5.25 (1.11) | 5.27 (0.98) | 5.11 (0.90) | 5.18 (0.94) | 5.21 (1.01) |

| Dactylitis in ≥1 digit | 43 (51.2) | 38 (57.6) | 30 (41.1) | 68 (48.9) | 111 (49.8) |

| Dactylitis score (0–60) | 9.88 (12.21) | 8.05 (11.00) | 6.70 (5.99) | 7.46 (9.10) | 8.40 (10.43) |

| Enthesitis | 66 (78.6) | 56 (84.8) | 57 (78.1) | 113 (81.3) | 179 (80.3) |

| Enthesitis score (0–15) | 5.23 (4.18) | 5.04 (2.99) | 6.54 (4.15) | 5.80 (3.68) | 5.59 (3.87) |

| Methotrexate | 33 (39.3) | 33 (50.0) | 41 (56.2) | 74 (53.2) | 107 (48.0) |

| Mean dose (SD) (mg/week) | 15.83 (4.87) | 14.09 (4.18) | 14.82 (3.97) | 14.49 (4.05) | 14.91 (4.34) |

| Corticosteroids | 16 (19.0) | 17 (25.8) | 14 (19.2) | 31 (22.3) | 47 (21.1) |

| Mean dose (SD) (mg/day) | 6.84 (2.23) | 7.71 (2.78) | 6.54 (2.76) | 7.18 (2.79) | 7.06 (2.59) |

| HLA-B27+patients* (N) | 13 | 13 | 14 | 27 | 40/158 (25.3) |

| Age | |||||

| <45 years | 7 (53.8) | 9 (69.2) | 8 (57.1) | 17 (63.0) | 24 (60.0) |

| ≥45 years | 6 (46.2) | 4 (30.8) | 6 (42.9) | 10 (37.0) | 16 (40.0) |

| Spondylitis-related activity (0–10) | |||||

| BASDAI total neck/back/hip pain | 5.54 (2.32) | 7.55 (2.29) | 7.40 (1.85) | 7.47 (2.03) | 6.88 (2.28) |

| mBASDAI (excl. peripheral) | 5.99 (1.33) | 7.16 (1.78) | 7.02 (1.55) | 7.09 (1.63) | 6.75 (1.61) |

| BASDAI | 6.18 (1.31) | 7.12 (1.66) | 6.97 (1.59) | 7.04 (1.59) | 6.78 (1.55) |

| ASDAS-CRP | 3.76 (0.82) | 4.55 (0.95) | 4.09 (0.79) | 4.31 (0.88) | 4.14 (0.89) |

| <45 years | 3.85 (0.68) | 4.85 (0.67) | 3.97 (0.84) | 4.44 (0.86) | 4.27 (0.84) |

| ≥45 years | 3.64 (1.05) | 3.87 (1.23) | 4.25 (0.76) | 4.10 (0.93) | 3.95 (0.96) |

| CRP (mg/L) | 26.30 (46.20) | 42.46 (38.05) | 20.60 (22.22) | 31.12 (32.23) | 29.56 (36.80) |

| HLA-B27– patients* (N) | 47 | 32 | 39 | 71 | 118/158 (74.7) |

| Age | |||||

| <45 years | 19 (40.4) | 11 (34.4) | 22 (56.4) | 33 (46.5) | 52 (44.1) |

| ≥45 years | 28 (59.6) | 21 (65.6) | 17 (43.6) | 38 (53.5) | 66 (55.9) |

| Spondylitis-related activity (0–10) | |||||

| BASDAI total neck/back/hip pain | 6.20 (2.76) | 6.53 (2.28) | 6.76 (2.03) | 6.66 (2.13) | 6.48 (2.40) |

| mBASDAI (excl. peripheral) | 6.29 (1.87) | 6.42 (1.93) | 6.63 (1.66) | 6.54 (1.77) | 6.44 (1.81) |

| BASDAI | 6.41 (1.72) | 6.45 (1.83) | 6.67 (1.63) | 6.57 (1.71) | 6.51 (1.71) |

| ASDAS-CRP | 3.67 (0.83) | 3.64 (0.87) | 3.88 (0.84) | 3.78 (0.86) | 3.74 (0.84) |

| <45 years | 3.68 (0.98) | 3.95 (1.10) | 3.81 (0.69) | 3.86 (0.82) | 3.79 (0.88) |

| ≥45 years | 3.67 (0.73) | 3.49 (0.71) | 3.97 (1.02) | 3.71 (0.89) | 3.69 (0.82) |

| CRP (mg/L) | 17.24 (20.63) | 12.60 (9.77) | 19.61 (18.74) | 16.45 (15.66) | 16.76 (17.73) |

*Does not include three patients with testing for whom the HLA-B27 genotype could not be determined.

ASDAS-CRP, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score incorporating C-reactive protein; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BSA, body surface area; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAS28-CRP, disease activity score 28-CRP; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; HLA-B27, human-leucocyte-antigen B27 allele; mBASDAI, modified Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; PA-PRS, peripheral arthritis and physician-reported spondylitis; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor-inhibitor.

For the overall TNFi-naïve PA-PRS subset, baseline mean BASDAI neck/back/hip pain, mBASDAI, BASDAI and ASDAS of 6.51, 6.54, 6.51 and 3.81, respectively, consistently indicated moderate-to-severe spondylitis-related disease activity. Baseline disease activity appeared comparable between HLA-B27+ and HLA-B27– patients, although serum CRP levels were numerically higher for HLA-B27+ versus HLA-B27– (29.6 vs 16.8 mg/L) patients. When evaluated by age group (<45 vs ≥45 years) within each of the HLA-B27+ and HLA-B27– subgroups, no consistent age-related differences in baseline mean ASDAS were observed and values across all patients within each age subgroup were consistently >3.5, indicative of very high disease activity. Consistent with observed numerical differences in serum CRP levels, mean baseline ASDAS appeared to be slightly numerically higher in HLA-B27+ versus HLA-B27– patients, irrespective of age (table 1).

Spondylitis-related symptoms

Treatment differences in the individual domains of the mBASDAI were evident by Week 12, and generally increased from Week 12 to Week 24. Of note, the mean change in neck/back/hip pain at Week 24 in ustekinumab-treated patients (−1.99) was >10- fold that observed in placebo-treated patients (−0.18) (table 2). Ustekinumab-treated HLA-B27+ patients demonstrated numerically greater improvements in both fatigue and neck/back/hip pain than HLA-B27– patients at both Week 12 and Week 24. At Week 24, placebo-treated HLA-B27+, but not HLA-B27–, patients had worsened fatigue and neck/back/hip pain. Improvements in entheseal pain and morning stiffness severity and duration were similar between HLA-B27+ and HLA-B27– patients (table 2).

Table 2.

Mean (SD) changes in mBASDAI component scores* among TNFi-naïve PSA patients with PA-PRS, overall† and by HLA-B27 status‡, at Week 12 and Week 24

| |

Week 12 | Week 24 | ||||||

| Ustekinumab | Ustekinumab | |||||||

| Placebo | 45 mg | 90 mg | Combined | Placebo | 45 mg | 90 mg | Combined | |

| Fatigue | ||||||||

| All patients | −0.37 (2.23) | −1.79 (2.39) | −1.64 (2.27) | −1.71 (2.32) | −0.33 (2.22) | −1.37 (2.44) | −2.14 (2.46) | −1.77 (2.47) |

| HLA-B27+ | 0.02 (2.56) | −1.80 (1.66) | −2.02 (2.20) | −1.91 (1.92) | 0.30 (2.87) | −1.78 (2.52) | −3.20 (1.78) | −2.49 (2.25) |

| HLA-B27– | −0.23 (2.30) | −1.88 (2.50) | −1.48 (2.52) | −1.65 (2.50) | −0.25 (2.05) | −1.13 (2.63) | −2.01 (2.68) | −1.61 (2.67) |

| Neck/back/hip pain | ||||||||

| All patients | −0.31 (2.10) | −1.66 (2.48) | −1.73 (2.74) | −1.69 (2.62) | −0.18 (2.35) | −1.66 (2.73) | −2.30 (2.47) | −1.99 (2.61) |

| HLA-B27+ | −0.07 (2.82) | −2.12 (2.06) | −2.54 (2.24) | −2.33 (2.12) | 0.83 (2.79) | −2.72 (2.85) | −2.66 (2.12) | −2.69 (2.46) |

| HLA-B27– | −0.31 (1.77) | −1.51 (2.40) | −1.66 (2.75) | −1.60 (2.59) | −0.29 (1.79) | −0.99 (2.65) | −2.49 (2.69) | −1.82 (2.76) |

| Pain at entheses | ||||||||

| All patients | −0.69 (2.02) | −1.94 (2.30) | −1.92 (2.48) | −1.93 (2.39) | −0.92 (2.21) | −1.86 (2.60) | −2.72 (2.81) | −2.31 (2.74) |

| HLA-B27+ | −0.83 (2.04) | −1.32 (2.66) | −2.62 (2.01) | −1.97 (2.40) | −0.74 (2.35) | −2.09 (2.88) | −2.78 (1.96) | −2.44 (2.44) |

| HLA-B27– | −0.69 (2.03) | −1.68 (1.70) | −1.94 (2.68) | −1.83 (2.30) | −0.89 (2.17) | −1.46 (2.58) | −2.98 (3.11) | −2.30 (2.96) |

| Morning stiffness severity | ||||||||

| All patients | −1.10 (2.06) | −2.16 (2.48) | −2.21 (2.49) | −2.18 (2.48) | −1.23 (2.19) | −2.67 (2.75) | −2.82 (2.76) | −2.75 (2.74) |

| HLA-B27+ | −1.03 (2.50) | −1.64 (2.02) | −2.26 (2.76) | −1.95 (2.39) | −1.62 (2.71) | −2.61 (2.80) | −2.69 (2.46) | −2.65 (2.58) |

| HLA-B27– | −1.14 (2.00) | −2.57 (2.40) | −2.52 (2.75) | −2.54 (2.59) | −1.12 (1.94) | −2.56 (2.68) | −3.01 (2.96) | −2.81 (2.82) |

| Morning stiffness duration | ||||||||

| All patients | −0.34 (2.94) | −1.55 (2.67) | −1.43 (3.01) | −1.49 (2.85) | −0.61 (2.34) | −2.01 (2.58) | −2.16 (2.95) | −2.09 (2.77) |

| HLA-B27+ | −0.79 (2.50) | −1.77 (2.83) | −1.28 (2.40) | −1.53 (2.58) | −0.75 (2.54) | −2.43 (2.82) | −3.15 (2.91) | −2.79 (2.83) |

| HLA-B27– | −0.20 (2.66) | −1.54 (2.91) | −1.77 (3.41) | −1.67 (3.18) | −0.52 (2.04) | −2.00 (2.88) | −2.16 (3.25) | −2.09 (3.07) |

*Among patients with component scores at each visit.

†Includes 84 placebo- and 139 combined ustekinumab- (66 [45 mg], 73 [90 mg])-treated patients.

‡Includes 13 placebo- and 27 combined ustekinumab- (13 [45 mg], 14 [90 mg])treated HLA-B27+ patients and 47 placebo- and 71 combined ustekinumab- (32 [45 mg], 39 [90 mg]) treated HLA-B27 – patients.

HLA-B27, human-leucocyte-antigen B27 allele; mBASDAI, modified Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; PA-PRS, peripheral arthritis and physician-reported spondylitis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor-inhibitor.

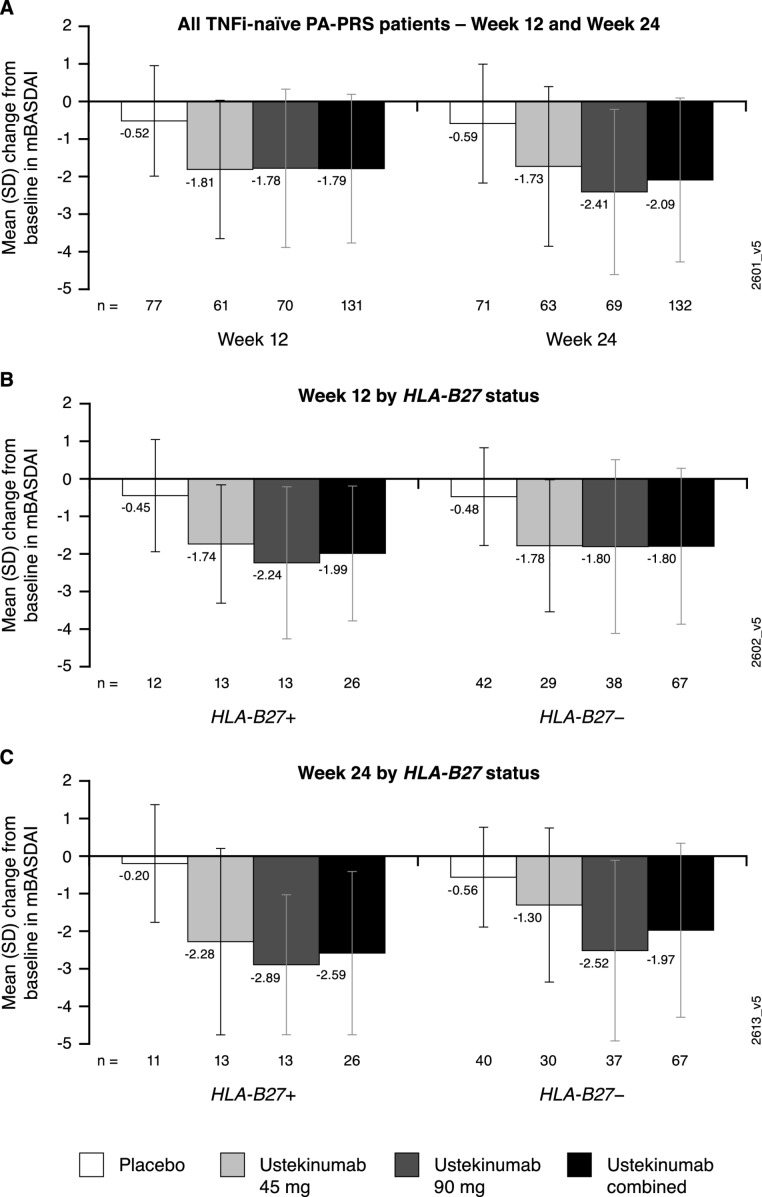

Mean changes from baseline to Week 12 and Week 24, respectively, in the mBASDAI score were generally consistent with improvements observed in neck/back/hip pain, i.e., −1.81 and −1.73 for ustekinumab 45 mg-treated and −1.78 and −2.41 for ustekinumab 90 mg-treated patients, versus −0.52 and −0.59 among placebo-treated patients (figure 1A). Similar treatment effects were observed when employing ASDAS response criteria (online supplementary figure). Driven by more robust improvements in fatigue (mBASDAI) and neck/back/hip pain (mBASDAI and ASDAS) discussed above, mean changes in the total mBASDAI scores and ASDAS response rates at these time points generally appeared greater in HLA-B27+ than HLA-B27– patients (figure 1B,C, online supplementary figure).

Figure 1.

Mean (SD) changes in mBASDAI score among TNFi-naïve PsA patients with PA-PRS at Week 12 and Week 24 (A) and by HLA-B27 status at Week 12 (B) and Week 24 (C). HLA-B27, human-leucocyte-antigen B27 allele; mBASDAI, modified Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; PA-PRS, peripheral arthritis and physician-reported spondylitis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor-inhibitor.

rmdopen-2019-001149supp001.pdf (121.5KB, pdf)

Discussion

In these post-hoc analyses of the pooled PSUMMIT studies, which focused on evaluating the efficacy of ustekinumab in treating spondylitis-related signs and symptoms among TNFi-naïve patients with PA-PRS, the average improvement in neck/back/hip pain at Week 24 in ustekinumab-treated patients was numerically greater than that observed in placebo-treated patients. Additional assessments employing the mBASDAI also indicated ustekinumab demonstrated meaningful improvement of spondylitis-related symptoms.

When evaluating the individual domains of the mBASDAI, improvements in entheseal pain and morning stiffness severity and duration were consistent between ustekinumab-treated patients who potentially meet the ASAS clinical criteria for axial disease (HLA-B27+ and at least two other SpA features)8 and those who do not. Improvements in fatigue and neck/back/hip pain, however, appeared to be numerically greater in HLA-B27+ than HLA-B27– patients at both Week 12 and Week 24.

Given that multiple immunological functions can be altered by a myriad of genetic polymorphisms, it is not surprising that individual SpA disorders have demonstrated heterogeneity in responses to biologic agents targeting the IL-23/IL-17 axis. IL-12/23p409–11 and IL-23p19 inhibitors are effective in PsA22 23 but not AS,13 24 while IL-17 inhibition is effective in AS and PsA, inclusive of axial manifestations.25 26 Specific to AS and PsA, it has been postulated that differing biologic mechanisms in the spine, where IL-23-independent production of IL-17 may occur, versus the periphery results in differential responses to IL-23 inhibition.27 28 Indeed, in a recently conducted prospective evaluation of >2000 patients with AS or PsA, AS patients, with or without psoriasis, differed demographically, genetically, clinically and radiographically from patients with axial PsA, leading the authors to conclude that axial PsA appears to be a distinct entity.29 Importantly, when evaluated prospectively in a real-world setting via the BIOPURE registry of PsA patients, ustekinumab demonstrated a 12-month drug survival of 87% in bio-naïve patients and retention rates were similar between patients with peripheral versus axial PsA.30

These study results are limited by the heterogeneous PsA patient group with PRS in the absence of imaging studies, the definitive approach to identify axial disease in PsA.31 Approximately 25% of these TNFi-naive PA-PRS patients were HLA-B27+, compared with 16% of patients without PA-PRS, in the combined studies. Among PsA patients, those who are HLA-B27+ carry a higher risk of developing axial disease.4 Given that a universally accepted definition of axial PsA is lacking, future studies will benefit greatly from the ongoing initiative by the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) and ASAS to delineate axial PsA classification criteria.7 Our results are also constrained by limitations inherent in the assessment tools employed. Historically, most of the instruments for PsA clinical trials have been borrowed or adapted from studies conducted in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and AS. Although the BASDAI is not adequately validated in PsA, in patients with axial PsA, ASDAS and BASDAI scores show similar good-to-moderate discriminative ability and correlate with different constructs of disease activity.17 The ASDAS has been validated in axial SpA, including in patients with axial PsA, and the mBASDAI score employed, i.e., without the peripheral joint component, has been shown to correlate well with constructs of disease activity.17 Nonetheless, as reported previously for the BASDAI in PsA patients,32 improvements in extra-axial domains, such as peripheral arthritis and enthesitis, may have contributed to the changes in both the ASDAS and mBASDAI scores we observed in ustekinumab-treated patients. The core outcome measurement set being developed by GRAPPA to standardise response measures in PsA33 will prove useful in future assessments of patients with axial PsA.

Noting these extensive limitations, these post-hoc study results suggest that ustekinumab may be an appropriate treatment option for TNFi-naive PsA patients with physician-reported signs and symptoms of spondylitis, irrespective of ASAS clinical classification criteria for axial SpA. Further, the numerically greater improvements in neck/back/hip pain—but not peripheral domains of disease activity—among HLA-B27+ ustekinumab-treated patients suggest ustekinumab may improve disease activity in TNFi-naïve PsA patients likely to exhibit axial disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michelle L. Perate, MS, a professional medical writer funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, for writing support. Portions of these data have been presented at the 2018 American College of Rheumatology annual meeting and were published in the meeting proceedings, that is, Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70 (suppl. 10) and can also be found at https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/efficacy-of-ustekinumab-on-spondylitis-associated-endpoints-in-tnf-naive-active-psoriatic-arthritis-patients-with-physician-reported-spondylitis/ (Accessed 18 October 2019).

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study design, YY conducted the data analysis, and all authors interpreted the data and revised the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Janssen Research & Development, LLC.

Competing interests: PH has received research grants and/or payments to third parties for lectures and educational material development/events (<$10 000) from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. DDG has received grants and/or consultancies (<$10 000) from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. SDC, SK and CSK are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs/Global Services and own stock in Johnson & Johnson, of which Janssen Scientific Affairs & Global Services are wholly owned subsidiaries. YY, KC and KS are employees of Janssen Research & Development, LLC and own stock in Johnson & Johnson, of which Janssen Research & Development, LLC, is a wholly owned subsidiary. AK has received consulting fees and research support from AbbVie, Amgen, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. LSG has received consulting honoraria from Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis and research grant support from AbbVie, Amgen, Pfizer, and UCB.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Additional data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. McGonagle DG, McInnes IB, Kirkham BW, et al. The role of IL-17A in axial spondyloarthritis and psoriatic arthritis: recent advances and controversies. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:1167–78. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sheehan NJ. The ramifications of HLA-B27. J R Soc Med 2004;97:10–14. 10.1177/014107680409700102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jadon DR, Sengupta R, Nightingale A, et al. Axial disease in psoriatic arthritis study: defining the clinical and radiographic phenotype of psoriatic spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:701–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feld J, Chandran V, Haroon N, et al. Axial disease in psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: a critical comparison. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2018;14:363–71. 10.1038/s41584-018-0006-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bowness P. HLA-B27. Annu Rev Immunol 2015;33:29–48. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen B, Li J, He C, et al. Role of HLA-B27 in the pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis. Mol Med Rep 2017;15:1943–51. 10.3892/mmr.2017.6248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goel N, FitzGerald O, Gladman DD, et al. GRAPPA 2018 Project Report. J Rheumatol 2019;95:54–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and for spondyloarthritis in general. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:25–31. 10.1136/ard.2010.133645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb AB, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT 1 trial. The Lancet 2013;382:780–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60594-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ritchlin C, Rahman P, Kavanaugh A, et al. Efficacy and safety of the anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite conventional non-biological and biological anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy: 6-month and 1-year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised PSUMMIT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:990–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin C, Rahman P, et al. Ustekinumab, an anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, inhibits radiographic progression in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results of an integrated analysis of radiographic data from the phase 3, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT-1 and PSUMMIT-2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1000–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kavanaugh A, Puig L, Gottlieb AB, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in psoriatic arthritis patients with peripheral arthritis and physician-reported spondylitis: post-hoc analyses from two phase III, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (PSUMMIT-1/PSUMMIT-2). Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1984–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-209068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deodhar A, Gensler LS, Sieper J, et al. Three multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:258–70. 10.1002/art.40728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, et al. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zochling J. Measures of symptoms and disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life Scale (ASQoL), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis disease activity index (BASDAI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Global Score (BAS-G), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI), Dougados Functional Index (DFI), and Health Assessment Questionnaire for the Spondylarthropathies (HAQ-S). Arthritis Care Res 2011;S11:S47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pavy S, Brophy S, Calin A. Establishment of the minimum clinically important difference for the Bath ankylosing spondylitis indices: a prospective study. J Rheumatol 2005;32:80–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eder L, Chandran V, Shen H, et al. Is ASDAS better than BASDAI as a measure of disease activity in axial psoriatic arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:2160–4. 10.1136/ard.2010.129726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lukas C, Landewé R, Sieper J, et al. Development of an ASAS-endorsed disease activity score (ASDAS) in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:18–24. 10.1136/ard.2008.094870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society ASDAS calculator. Available: http://www.asas-https://www.asas-group.org/clinical-instruments/asdas-calculator/ [Accessed 8 Aug 2019].

- 20. Machado P, Landewé R, Lie E, et al. Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease activity states and improvement scores. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:47–53. 10.1136/ard.2010.138594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van der Heijde D, Lie E, Kvien TK, et al. ASDAS, a highly discriminatory ASAS-endorsed disease activity score in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1811–8. 10.1136/ard.2008.100826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deodhar A, Gottlieb AB, Boehncke W-H, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. The Lancet 2018;391:2213–24. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30952-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mease PJ, Kellner H, Morita A, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab, a selective IL-23p19 inhibitor, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis over 24 weeks: results from a phase 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77 Oral presentation 0307. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baeten D, Østergaard M, Wei JC-C, et al. Risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor, for ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept, dose-finding phase 2 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1295–302. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lubrano E, Perrotta FM. Secukinumab for ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2016;12:1587–92. 10.2147/TCRM.S100091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Baraliakos X, Coates LC, Gossec L, et al. Secukinumab improves axial manifestations in patients with psoriatic arthritis and inadequate response to NSAIDs: primary analysis of the MAXIMISE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78 Oral presentation 0235. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Siebert S, Millar NL, McInnes IB. Why did IL-23p19 inhibition fail in AS: a tale of tissues, trials or translation? Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:1015–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mease P. Ustekinumab fails to show efficacy in a phase III axial spondyloarthritis program: the importance of negative results. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:179–81. 10.1002/art.40759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Feld J, Ye JY, Chandran V, et al. Is axial psoriatic arthritis distinct from ankylosing spondylitis with and without concomitant psoriasis? Rheumatology 2019:pii: kez457 10.1093/rheumatology/kez457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Iannone F, Santo L, Bucci R, et al. Drug survival and effectiveness of ustekinumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Real-life data from the biologic Apulian registry (BIOPURE). Clin Rheumatol 2018;37:667–75. 10.1007/s10067-018-3989-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Felbo SK, Terslev L, Østergaard M. Imaging in peripheral and axial psoriatic arthritis: contributions to diagnosis, follow-up, prognosis and knowledge of pathogenesis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2018;36:S24–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taylor WJ, Harrison AA. Could the Bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index (BASDAI) be a valid measure of disease activity in patients with psoriatic arthritis? Arthritis Rheum (Arthritis Care Res) 2004;51:311–5. 10.1002/art.20421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Orbai A-M, de Wit M, Mease P, et al. International patient and physician consensus on a psoriatic arthritis core outcome set for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:673–80. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2019-001149supp001.pdf (121.5KB, pdf)