Abstract

Significance: Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are now widely recognized as central mediators of cell signaling. Mitochondria are major sources of ROS.

Recent Advances: It is now clear that mitochondrial ROS are essential to activate responses to cellular microenvironmental stressors. Mediators of these responses reside in large part in the cytosol.

Critical Issues: The primary form of ROS produced by mitochondria is the superoxide radical anion. As a charged radical anion, superoxide is restricted in its capacity to diffuse and convey redox messages outside of mitochondria. In addition, superoxide is a reductant and not particularly efficient at oxidizing targets. Because there are many opportunities for superoxide to be neutralized in mitochondria, it is not completely clear how redox cues generated in mitochondria are converted into diffusible signals that produce transient oxidative modifications in the cytosol or nucleus.

Future Directions: To efficiently intervene at the level of cellular redox signaling, it seems that understanding how the generation of superoxide radicals in mitochondria is coupled with the propagation of redox messages is essential. We propose that mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) is a major system converting diffusion-restricted superoxide radicals derived from the electron transport chain into highly diffusible hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). This enables the coupling of metabolic changes resulting in increased superoxide to the production of H2O2, a diffusible secondary messenger. As such, to determine whether there are other systems coupling metabolic changes to redox messaging in mitochondria as well as how these systems are regulated is essential.

Keywords: SOD2, MnSOD, redox signaling, H2O2

Introduction

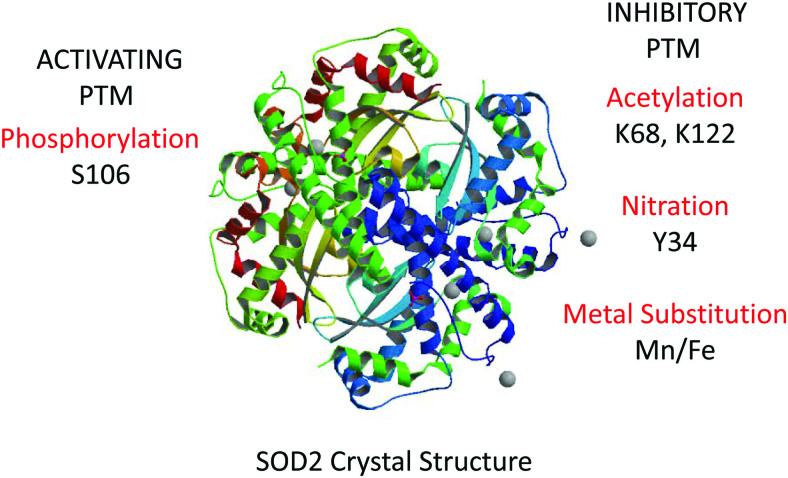

Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) is a major component of the metabolic machinery that handles reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the mitochondrial matrix. Specifically, SOD2 determines how much superoxide radical anion (O2•−) is converted to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (42, 90, 129) (Fig. 1). This dismutase function of SOD2 is unlike that of most mammalian SOD enzymes that use copper and zinc (42). Instead, SOD2 uses manganese (Mn) for which it has only moderate affinity. Stranger still, it can even incorporate iron (Fe), although this does not support its dismutase activity (29, 43). SOD enzymes that bind Fe and Mn are generally only observed in bacteria, perhaps related to the important role of SOD2 in mitochondria and the proposed prokaryotic origins of this organelle (35, 94, 135). A connection to the ancient origins of our aerobic metabolism is perhaps not surprising given more than 40 years of studies that have firmly established SOD2 as a critical antioxidant enzyme in mitochondria (59, 124, 125). Its deletion, inhibition, or suppression causes significant oxidative damage to a variety of proteins. A prime example is aconitase, which catalyzes the conversion of citrate into isocitrate in the second step of the Kreb's cycle. The oxidation of aconitase by superoxide has received considerable attention and will be discussed in greater detail later (69, 97). Briefly, aconitase is an iron–sulfur cluster-dependent enzyme and oxidative damage to the aconitase's iron–sulfur moiety compromises its enzymatic activity, leading to catastrophic consequences for mitochondrial metabolism (64). This kind of dysfunction in the Kreb's cycle is now known to provoke changes to cellular metabolism (93, 106, 136) that have historically been associated with malignant transformation and carcinogenesis (26, 51, 108, 116). In this way, the fact that SOD2 protects Kreb's cycle enzymes from oxidation is consistent with its well-established role as a suppressor of tumor initiation. Consistent with this, several studies have found that SOD2 deletion promotes (33, 131) whereas SOD2 reconstitution inhibits xenograft tumor growth, invasiveness, and tumorigenicity (32, 54, 89, 128, 132, 133). This is seen in several cancer types, including those of the prostate, breast, digestive tract, and nervous system. The long-held view that SOD2 is a prototypical tumor suppressor is contrasted, however, with the observation that in most aggressive, invasive, high-grade tumors, SOD2 is overexpressed. SOD2 overexpression can be several fold higher than in parental tissue or tumors of the same kind at earlier stages (33, 52–54, 61, 78, 99). This dichotomy is puzzling, but may be explained by new findings of post-translational modifications (PTMs) (Fig. 2) that regulate the structure and activity of SOD2 (44, 57, 113), and even endow the enzyme with completely novel biological functions (3, 44, 57). These new findings provide a mechanistic framework for the distinct roles of SOD2 in different stages of tumor evolution.

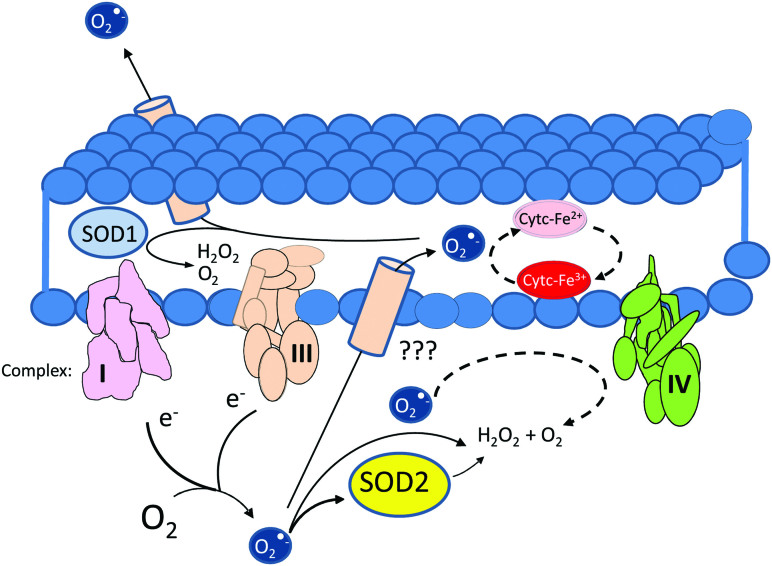

FIG. 1.

Sources and potential obstacles to the diffusion of O2•− from the mitochondrial matrix to the extracellular space depicting SOD1 and cytochrome c as major obstacles present in the intermembrane space and SOD2 as a major sink in the matrix. O2•−, superoxide radical; SOD, superoxide dismutase; SOD2, mitochondrial superoxide dismutase. Color images are available online.

FIG. 2.

Structure of the SOD2 homotetramer with major known activating and inhibiting PTMs. Crystal structure was downloaded from Swiss PDB Viewer Protein Structure Database. PTM, post-translational modification. Color images are available online.

Although SOD2 is a long-studied enzyme with well-established functions, more recent observations suggest that entirely new roles and activities for SOD2 exist. This review will present the established understanding of SOD2 function, discuss the intriguing new findings that hint at limitations in this established view, and explore novel, recently described aspects of SOD2 biochemistry. These new mechanisms can help to understand the complex, dichotomous, and vital roles of SOD2 in inter-organellar communication and signaling.

SOD2: The Established and the New

Decades of research on SOD2 have detailed the enzyme's structure, enzymatic function, and how its dysregulated expression (too much or too little) alters cellular and organ function. Therefore, this first section will focus on the chemistry, biochemistry, and pathophysiology of SOD2. We critically review existing observations to suggest roles for SOD2 that extend far beyond scavenging superoxide to focus on its potentially more important role as a source of H2O2. The understanding of this diffusible oxidant has evolved tremendously. H2O2 was previously thought of only as a source of oxidative injury, but it is now recognized as a key messenger in redox signaling (9, 83, 102). The understanding of SOD2, a key regulator of H2O2 formation, is due for a similar update.

The chemistry

SOD2 is classically viewed exclusively as a dismutase of superoxide radicals produced during the reduction of molecular oxygen (O2) to H2O by the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC). In the process of O2 reduction, an electrochemical gradient is generated between the mitochondrial matrix and the intermembrane space, which is used to power adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production by F0F1 ATPase. Although this process is >99% efficient (38, 72), there is a small but important fraction of O2 that is incompletely reduced producing ROS.

Superoxide comprises the vast majority of the ROS directly produced from electrons that enter the ETC (24, 49, 103, 109, 117, 123). SOD2 is generally thought to act as an essential catalyst of superoxide dismutation, thereby preventing it from further reacting with metal centers such as the iron–sulfur clusters used as cofactors in numerous mitochondrial proteins. However, the dismutation of superoxide radicals is itself a spontaneous process that occurs rapidly around neutral pH (k ∼ 106 M−1 s−1 at pH 7). Although this proton-catalyzed reaction is slowed by the alkaline environment of the mitochondrial matrix (pH 7.8) (96), it remains quite rapid there (110). SOD2 accelerates this further, 100–1000 times (110). However, the reaction rates of O2•− with other targets in the mitochondrion and the ultimate fates of these targets are poorly understood, as is the real requirement for SOD2 in protecting matrix components from the oxidative power of superoxide. We discuss these questions next.

Superoxide radicals as oxidants: Is superoxide that powerful as an oxidant?

The power of superoxide as an oxidant can vary, and it depends largely on pH. Protonated hydroxyperoxyl radicals (prevail below ∼pH 5) are relatively powerful oxidants (E0HO2•/H2O2 = 1.06 V), whereas superoxide radicals themselves are not (E0O2•−/O2 = −0.33 V) (16). The negative standard oxidizing potential versus normal hydrogen electrode suggests that superoxide radical functions best as a reductant, instead “preferring” to give away its unpaired electron to yield O2. Although oxidizing potentials are impacted by several physicochemical variables, the standard oxidizing potential E0 is adequate to estimate relative oxidizing or reducing capacity. For example, the reductive behavior of O2•− is demonstrated by its capacity to reduce isolated cytochrome c from its oxidized ferricytochrome c-Fe(III) form (which has a strong absorption band centered around ∼530 nm) to cytc-Fe(II), which has a significant absorption band shift toward 550 nM (40, 86). This example helps to address the second question regarding the fate of substrates reacting with superoxide radical anions.

What happens to matrix components when they encounter superoxide radicals?

To better understand the potential fate of its substrates, it is important to understand what species superoxide will preferentially target. Because this radical anion has an odd number of electrons, its reactions with diamagnetic molecules are kinetically disfavored, even if they are thermodynamically possible (Table 1). This actually means that superoxide will preferentially react (or react significantly faster) with cofactors and molecules bearing an odd number of electrons; these include other free radicals such as nitric oxide (•NO) (8) and metallic cofactors, which are far more abundant in the environment of the mitochondrial matrix (48, 100). In addition, activated thiolate groups (such as those found in Fe–S clusters) are targeted because the thiolate is generally an order of magnitude more reactive toward oxidants than its analogous thiol group.

Table 1.

Bimolecular Reaction Rate Constants for Superoxide Radical Reactions with Mitochondrial Matrix Components and Other Model Compounds

| Matrix component | k (M−1 s−1) for the reaction with O2•− | References |

|---|---|---|

| SOD2 (MnSOD) | kcat = 1.95 × 108 (Thermus thermophilus), 25°C | (17) |

| Aconitase | k = 3–6 × 106 | (39) |

| Fumarase | k = 2–6 × 106 | (39) |

| HO2• (peroxyl radical) | k = 9 × 107 | (11) |

| Cytochrome c oxidase | k = 2 × 107 | (50) |

| Metallothionein | k = 4 × 105 | (115) |

| Cytochrome c-Fe(III)a | k = 6.1 × 106 | (5) |

| FAD and FMN semiquinone radicals | k = 2–4 × 108 | (3) |

| Hemoglobinb | k = 6.5 × 106 | (74) |

Cytochrome c is localized to the intermembrane space.

Hemoglobin is not in mitochondria, listed as an example of heme-containing protein.

MnSOD, manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase; O2•−, superoxide radical; SOD2, mitochondrial superoxide dismutase.

On reaction with the oxidized form of metallic cofactors, the odd electron reduces the metal. This mechanism underlies the first half cycle of SOD2's catalytic activity or the reduction of ferricytochrome c. In the case of Fe–S clusters, the thiolate moiety is oxidized, leading to decomposition of the cluster, release of the metal in a manner analogous to the reaction with H2O2, and inactivation of the enzymatic function that required the Fe–S cluster (45, 66, 71). This is why inactivation of the Fe–S cluster-dependent aconitase enzyme is often interpreted as a proxy for mitochondrial superoxide production, but as mentioned, aconitase deserves a dedicated discussion that is found next. Beyond the more likely scenarios that superoxide will react with SOD2 or metal-cofactors, it could also reintroduce the leaked electrons back into the ETC. This would require its reaction with an electron transferring center in the ETC, such as flavin-derived moieties, heme-dependent cytochromes, or semiquinone intermediates without major consequences for the redox state of the matrix. Table 1 shows some known reaction rate constants for superoxide reactions with mitochondrial matrix components and other molecules).

Is SOD2 really necessary to protect matrix components from O2•−?

Based on the analysis presented earlier, we argue that except in very special cases, SOD2 performs only a minor role in defending Kreb's cycle enzymes from superoxide-mediated oxidation. This is based on the fact that the reaction of O2•− with heme groups, metal cofactors, flavin semiquinone radicals, and even itself is just as fast or faster than its reaction with aconitase or fumarase. An important exception is the reaction of •NO with O2•− to form the powerful oxidant peroxynitrite (ONOO−), a reaction whose rate is limited by the diffusion of the reactants. However, it is extremely unlikely that SOD2 functions primarily as an antioxidant for the following reasons: (i) SOD2 dismutates superoxide to generate H2O2, which is itself a fairly strong oxidant (E0H2O2/H2O = 1.78 V) that is capable of reacting rapidly with Fe–S clusters (k > 103 M−1 s−1) (56); (ii) the spontaneous dismutation of superoxide radicals as well as the reaction with electron transferring moieties of ETC components are relatively fast and consume a significant fraction of superoxide radicals before they react and oxidize diamagnetic compounds; and (iii) there are several electron-transferring and electron-carrying moieties in mitochondria that could scavenge and neutralize the superoxide radical anion without necessarily leading to oxidative inactivation. Still, if the primary function of SOD2 is not as an antioxidant, what could SOD2 be doing in mitochondria?

An intriguing idea is that SOD2 functions to broadcast redox signals generated by mitochondria to distant sites in the cytosol, nucleus, or even outside of the cell. In the presence of SOD2, O2•− is converted to H2O2, at a 2:1 ratio. H2O2 is a freely diffusible oxidant, and it has a prominent role as a regulator of signaling systems based on redox-sensitive thiol switches such as thiol-phosphatases and proteases (27, 37, 77, 101). Because the pH of the mitochondrial matrix is slightly alkaline, the generation of H2O2 from the spontaneous dismutation of O2•− is expected to be slower than at neutral pH. The efficiency of the spontaneous dismutation would also be variable as it is expected to depend on generation rates, the metabolic state of mitochondria, and O2 tension variations as well as protein expression and matrix composition changes. SOD2 eliminates much of this variability, because the reaction between SOD2 and O2•− is nearly diffusion controlled; thus, the generation of H2O2 obeys a stoichiometric relationship depending solely on the concentration and activity of the enzyme and the levels of superoxide. New post-translational mechanisms, described next, that control SOD2 activity indicate that SOD2 is the cornerstone of a sophisticated redox signaling system that allows electron flow efficiency through the ETC to exert regulatory control over events happening in the extramitochondrial space.

The biochemistry

SOD2 is a tetramer of four identical subunits, each carrying a manganese atom. Both the manganese and the tetrameric quaternary structure are essential for the SOD catalytic activity. Another critical determinant of activity is the acetylation state of two critical lysine residues at the entrance of the cationic channel that guides superoxide anions toward the active site (K68 and K122) (113, 134). Acetylation of either of these lysines hinders access of superoxide and inhibits SOD2 dismutase activity. Modification of these sites (134) is highly impacted by the metabolic state of mitochondria, with a reduction in ETC activity strongly promoting acetylation (114). Deacetylation is performed by Sirtuin-3, which requires NAD+ for function. Thus, a reduction in ETC performance results in accumulation of NADH, lower NAD+ levels, reduced Sirtuin-3-mediated SOD2 deacetylation, and, thus, a decrease in SOD2 activity (55).

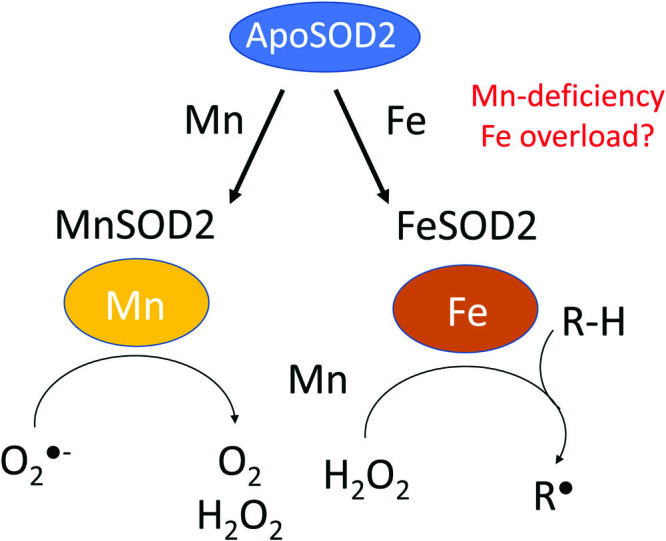

In addition to the inhibitory acetylation of K68 and K122, there has been a recent surge in the number of PTMs reported to affect SOD2 activity (23, 98, 113). Phosphorylation of serine S106 by cyclin-dependent kinase 4 was shown to increase SOD2 activity, and this is proposed to improve adaptation to radiation (57). Also, methylation of SOD2 lysines 68, 89, 122, and 202 as well as arginines 197 and 216 (105) has been reported to regulate superoxide radical accessibility to the active site. These PTMs endow SOD2 with the capacity to operate as a metabolic switch that controls cellular exit from quiescence and entrance to the proliferative phase of the cell cycle. Even more drastic modifications have been described that dramatically change the biological function of SOD2, including a switch in metal ion incorporation from manganese to iron (43). When MCF7 cells, a human breast adenocarcinoma cell line, were cultured in media deficient in Mn, or mice were fed Mn-deficient diets, SOD2 was found to accumulate in an iron-bearing form (iron-dependent superoxide dismutase [FeSOD2]). FeSOD2 displayed no SOD activity, but instead demonstrated peroxidase activity, using H2O2 as a substrate to oxidize other molecules via one-electron transfer mechanisms (43) (Fig. 3). Consequently, this indicates that under specific conditions SOD2 acts as a pro-oxidant, a novel activity radically different from its established antioxidant function. The implications of this for cellular pathophysiology are only beginning to be explored.

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of the reactions catalyzed by MnSOD2 and FeSOD2, which exhibit SOD and pro-oxidant peroxidase activity, respectively. FeSOD2, iron-dependent superoxide dismutase; MnSOD, manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase. Color images are available online.

The case of aconitase

Aconitase catalyzes the second step in the Kreb's cycle, the conversion of citrate to isocitrate. It is also widely accepted as a major target of superoxide radicals in the mitochondrial matrix. SOD2 suppresses the superoxide radical-dependent inactivation of aconitase, and this protective effect is interpreted as the defining example of the universal antioxidant function of SOD2 in mitochondria. But this interpretation is complicated by the accepted enzymatic function of SOD2 that culminates with the production of the powerful oxidant, H2O2, at a 2:1 (O2•−/H2O2) ratio. H2O2, itself, rapidly inactivates aconitase (79, 122), so it is difficult to accept the idea that SOD2, alone, prevents the oxidative inactivation of aconitase. It is clear, however, that aconitase is inhibited by superoxide, but the question remains as to whether this inhibition occurs in the microenvironment of the mitochondrial matrix.

In a series of studies that became landmark research pieces in the field, Gardner and Fridovich showed that aconitase is rapidly oxidized by superoxide radicals in vitro, and that addition of (Mn)SOD2 partially protects Escherichia coli aconitase from inactivation in a concentration-dependent manner (45–47). In addition, catalase alone was unable to protect aconitase, a result that is often interpreted as aconitase being resistant to H2O2-mediated inactivation. An alternative explanation, based on previous findings from the same group, is that superoxide radicals inhibit catalase (63). Superoxide radical-inhibited catalase then would become unable to protect aconitase from H2O2-driven inactivation in this in vitro binary (aconitase/catalase) context. Catalase is not a mitochondrial enzyme, and in mitochondria H2O2 is actually scavenged and reduced to water by peroxiredoxins (PRDXs), glutathione peroxidases (GPXs), and thioredoxin, all of which are abundant in mitochondria and impacted by the capacity of the organelle to maintain an environment that promotes the regeneration of reduced thiol/selenol-dependent reductases (95, 119, 102). In addition, Gardner and Fridovich (46, 47) also found that the presence of relatively low levels of citrate inhibits the reaction of superoxide with aconitase (the rate constant drops >100-fold), favoring instead the spontaneous dismutation of superoxide or reaction with other targets that are less affected by citrate. The implications of the lack of mitochondrial catalase or citrate inhibition on the likelihood of SOD2-protecting aconitase in mitochondria are rarely discussed.

Resolving the debate over the primary function of SOD2 will require new research aimed at determining the molecular constituency of mitochondria at the sub-organellar level, how metabolite concentrations are regulated and maintained, what mechanisms control the redox state of the organelle, and what structural features of mitochondria restrict and/or guide the transit of ROS through the organelle. In addition, it would be helpful to understand the role of SOD2 separately for metabolic and redox signaling functions of mitochondria, something that recent reports suggest may be possible (76). However, it is becoming clear from available observations that thinking about SOD2 should, at a minimum, not be restricted to mitochondrial antioxidant functions. Instead, it is possible that the SOD activity, itself, could be leading to H2O2 waves that promote redox signaling and extend the regulatory domain of the mitochondrion.

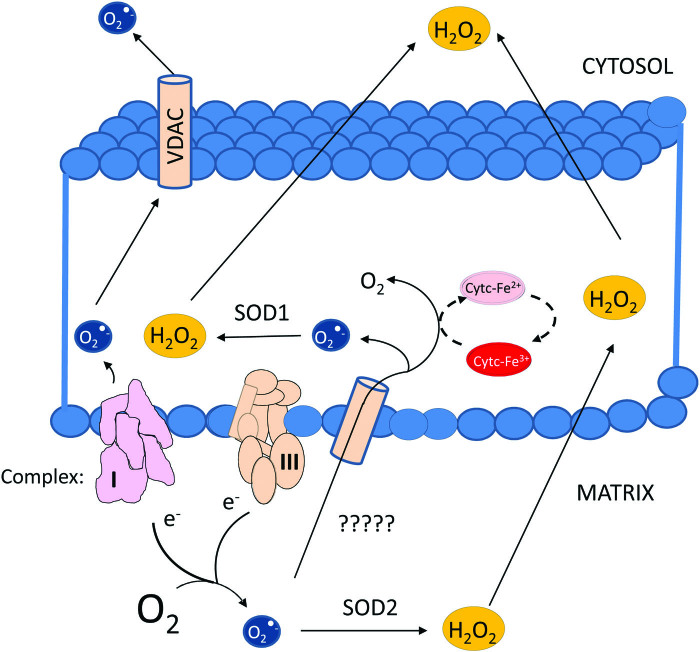

The pathophysiology, rethinking radicals

The field of “redox biology” has witnessed considerable change over the years. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and reactive nitrogen species) have evolved from exclusively damaging chemical species to key enablers of signal transduction. Although the thinking about the roles of ROS has changed dramatically, the understanding of the enzymes that control their stability, diffusion, reactivity, and interconversion has not. This is particularly true in the case of SODs, and chief among them, SOD2. SOD2 is strategically positioned at the mitochondrial matrix where it can convert O2•− emanating from complex I or complex III into O2 and H2O2. This is an important function because O2•− cannot simply cross membranes due to its charged anionic character. Although it has been shown that the voltage-dependent anion-selective channel (a channel localized mostly to the outer membrane) allows the exit of O2•− from the intermembrane space to the cytosol (73), evidence indicating that matrix-generated O2•− can reach the intermembrane space is lacking (80). This makes the conversion of O2•− to diffusible H2O2 in the mitochondrial matrix important for enabling mitochondrial redox signaling to propagate to the extramitochondrial space (Fig. 4). H2O2 can still be scavenged in the mitochondrion, of course, by PRDXs and GPX (28, 36, 82). However, a critical consideration is that these enzymes are dependent on NADPH. Hence, their ability to scavenge ultimately depends on the metabolic status of the cell and mitochondria themselves. These facts suggest yet another link between the mitochondrial metabolic status and the regulation of H2O2-dependent mitochondrial signaling.

FIG. 4.

Diagram illustrating the potential for diffusion of either superoxide radicals or H2O2 from the mitochondrial matrix to the extramitochondrial space. H2O2, hydrogen peroxide. Color images are available online.

There are multiple barriers to O2•− diffusion in the intermembrane space. These include the presence of cytochrome c, which can rapidly react with superoxide (Table 1). SOD1 is also resident in this space, presenting another significant obstacle to superoxide (87). Therefore, an intriguing concept is that the primary role of SOD2 is to regulate the production of H2O2 signals to convey information about the status of ETC (via O2•−/H2O2 signals) to the rest of the cell. This would permit adaptations to compensate for deficiencies in ETC performance. For instance, it has been shown that mitochondrial H2O2 or ROS are indispensable for the stabilization of the α-subunits of hypoxia-induced factors, which are essential to activate adaptive responses to lower oxygen tensions in cells (10, 21) that impair the functioning of the ETC at full capacity for lack of oxygen, the final electron acceptor.

In addition, there are many signal transducing enzymes that are sensitive to H2O2. These include thiol-containing phosphatases, such as protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) and phosphatase and tensin homolog (27). These enzymes are particularly sensitive to H2O2 inhibition because of the low pKa of their active site thiolate moieties (pKa ∼4.7) (130) (pKa ∼4.5) respectively (111). Other examples include PTPs (i.e., protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B) and small heterodimer partners (12, 13, 30). Inhibition of these enzymes favors the accumulation of their target substrates in the phosphorylated state. Hence, an increase in intracellular H2O2 favors the phosphorylation of broad arrays of proteins by suppressing dephosphorylation rather than promoting kinase activity. The duration of this large-scale change in phospho-proteome regulation is itself controlled by the metabolic state. This is due to the fact that NADPH is directly or indirectly required for the enzymatic machinery that reduces glutathione and sets the cellular capacity to quench H2O2, including GPX, PRDXs, thioredoxin, and other primary and secondary thiol reductants (81). Hence, in an integrated manner, the different sensitivities of phosphatases to H2O2 as determined by the pKa of their active thiolate moieties, the kinetics of active site reduction, and the availability of reductants produced by the cellular metabolism all combine to provide a complex redox circuit with multiple switches and points of regulation that, in turn, support a sophisticated messaging system where SOD2 plays a central role.

The SOD2 Goldilocks Effect: Too Much or Too Little?

Multiple studies examining the effects of overexpression or suppression of SOD2 indicate that significant changes in the levels of SOD2 activity cause major problems, leading to cellular adaptive responses with adverse impacts on organ function and even survival. Both increased and decreased SOD2 expression have been linked to disease. This section reviews studies that used knockdown or knockout strategies to reduce SOD2 expression either globally or in specific tissues, and also discusses observations of problems associated with too much SOD2.

Too little SOD2, a big problem

Several genetically manipulated mouse models have been generated to target SOD2. These include a range of strategies that span attenuated expression, such as a deletion targeting exon 3 that produces a shortened version of the SOD2 mRNA, all the way to precision disruptions such as the tissue-specific deletion of the entire gene using the Cre/lox approach. One of the first studies published on SOD2 deletion reported that SOD2-deficient mice died within a few days after birth, presenting clear indications of dilated cardiomyopathy on postmortem analysis. They observed reductions in aconitase and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activities ranging from ∼20% to 40%, depending on the tissue. Interestingly, however, the authors found no signs of oxidative or structural damage to mitochondria (69). Other authors describe deletions in SOD2 from various tissues, brain (85), liver (68), mammary gland (19), stomach (58), and kidney (91). The effects of these SOD2 disruptions range from significant mitochondrial ultrastructural changes with severe phenotypes, such as what is observed for deletion in the brain, to mild or undetected changes at baseline, such as when SOD2 is deleted in the mammary gland or kidney. Where analyzed, most studies found significant reductions in the activities of aconitase or SDH, disruptions in lipid metabolism with the accumulation of lipids stored in tissue, and increases in inflammatory and oxidative markers including protein nitrotyrosine modifications and lipid peroxidation. In the case of hepatocytes, for example, a reduction of SDH activity was observed. Despite this, there was no loss of mitochondrial DNA integrity (31). Although many studies reported an increase in “ROS” generation, these findings rely on probes such as dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate and dihydroethidium that present significant methodological concerns (15, 41), and thus preclude an accurate quantification of the changes in mitochondrial ROS caused by SOD2 deletion. Loss of SOD2 in the brain caused demyelination, which is consistent with defects in lipid metabolism and the development of neurological disorders ranging from seizure to paralysis (85). Nonetheless, partial loss of succinate dehydrogenase subunit B activity is unlikely to be sufficient for the dramatic phenotypes displayed by SOD2−/− mice, such as perinatal lethality. This is supported by the fact that heterozygosity in this enzyme has little effect, since SDHD+/− mice displayed no severe phenotypes up to 6 months of age. Therefore, even substantial reductions in SDH activity as assessed in heterozygote mice (ca. 50%), greater than those reported in the case of SOD2−/− mice (ca. 40%), were unable to recapitulate the dramatic phenotype caused by the loss of SOD2 (92).

In humans, deficiency of aconitase activity caused by mutations in the aconitase 2 (Aco2) gene leads to severe neurological disorders. On average, patients with Aco2 gene mutations displayed reductions of ∼20-fold in the levels of isocitrate in plasma compared against healthy subjects. Still, even in cases of profound impairment in intellectual development or other neurological conditions, the vast majority of the individuals recruited for the study were older than 10 years of age at the time of the study (1). Experiments with aconitase (Aco2)-deficient mice are ongoing, but preliminary results from the international mouse phenotyping consortium indicate that they recapitulate the phenotypes seen in patients with Aco2 mutations. The significant loss of mitochondrial aconitase activity in mice with only one functional SOD2 allele (SOD2+/−) can be inferred from data to be ∼35%–50% of wild type, depending on the specific organ and age of mice (70, 121, 127). Despite potent defects in Kreb's cycle activity, these animals do not recapitulate the perinatal lethality phenotype observed in the mice with homozygous loss of the SOD2 gene. In fact, the heterozygous SOD2 mice, which demonstrate a loss of ∼50% in SOD2 expression, are phenotypically indistinguishable at baseline from their wild-type controls. Regardless, SOD2+/− also show reduced cardiac aconitase activity (ca. 35%) (121) comparable to SOD2−/− mice (22%–42.6% depending on the tissue) (69). This strongly suggests that the impairment in mitochondrial aconitase activity caused by the reduction in SOD2 expression also cannot fully recapitulate the neonatal lethal phenotype seen in SOD2−/− mice (127). It is true from the published studies that age has an important impact on the reduction of aconitase activity in SOD2+/− mice. Even so, significant functional defects in aconitase were observed in mice by 6–9 months of age, and yet mice still lived to 18 months and beyond (70). Hence, it is unlikely to be true that the dramatic lethality phenotype observed in SOD2−/− animals can be fully accounted for by increased mitochondrial oxidative stress, leading to aconitase inactivation (67). So, if not the loss of aconitase activity, then why do SOD2−/− mice die so soon after being born into an oxygen-rich environment? A complete answer to this question will certainly require additional experimental work, but close examination of key findings from the study of SOD2−/− animals provides a few clues. One observation was that SOD2−/− mice showed lower levels of mitochondrial ATP production, indicating lower mitochondrial performance. Others have also shown that oxidants from mitochondria (14, 75, 88) are critical for initiating the process of mitochondrial biogenesis. This process is essential for the renovation of the cellular mitochondrial pool because it replaces worn out organelles with newly synthesized, fully functional ones (Fig. 5). As discussed, SOD2 plays an important role in promoting mitochondria redox signaling by converting superoxide radicals to H2O2. In this model of SOD2 function, the inability to activate mitochondrial biogenesis via SOD2-derived H2O2 causes the accumulation of aged mitochondria that are incapable of supporting robust metabolism or vigorous tissue growth and development, which could produce adverse outcomes for tissues and even death due to energetic crisis.

FIG. 5.

Diagram illustrating the hypothesis that SOD2 (functioning as a dismutase of superoxide) is essential to produce H2O2 signals necessary for the elimination of worn out mitochondria and the production of new functional mitochondria. Color images are available online.

Although significantly more complex and challenging to empirically test, the redox signaling model of SOD2 function accommodates most of the critical observations from the heterozygous and homozygous SOD2 systems, including: (i) a non-lethal reduction in aconitase and SDH activities in SOD2+/− that are, nevertheless, quantitatively comparable to those measured in SOD2−/−; (ii) an increase in mitochondrial protein oxidation characteristic of old/worn out or damaged underperforming mitochondria (18, 120); (iii) worsening metabolic syndrome with flagrant impairments in lipid metabolism that is also characteristic of underperforming mitochondria (84, 126); (iv) progressive reduction of ATP synthesis (65, 107); and (v) partial rescue of the phenotype with SOD2 mimetics such as Mn-porphyrins that are capable of converting O2•− into H2O2 (7), thereby restoring redox signaling through pharmacological restoration of mitochondrial H2O2 signaling, although in a less regulated manner than native SOD2. In this sense, increases in mitochondrial protein oxidation could contribute to the significant but non-lethal phenotypes seen in SOD2+/−. Another possibility is that mitochondrial H2O2 is required to regulate mitochondrial dynamics, and this would involve the segregation of underperforming segments of the interconnected mitochondrial network, and targeting them for degradation. This idea is supported by recent findings indicating that ROS signaling regulates mitochondrial dynamics (25, 62, 118) and mitophagy (104).

The capacity to generate new mitochondria, or segregate and eliminate malfunctioning mitochondrial segments, is essential for maintaining robust energetic and metabolic performance. Drastic changes in ROS signaling caused by SOD2 deficiency could manifest as metabolic dysfunctions that are severe enough to compromise tissues or even survival, as seen in the dramatic phenotypes of SOD2−/− animals when they become metabolically independent in an aerobic environment. In this model, SOD2 serves as a major hub in the network of cellular redox signaling, functioning as a transducing molecule involved in many aspects of mitochondrial quality control, mitochondrially regulated cellular development, and mitochondrial functional maturation. In support of this idea, a study by Domann and colleagues (20) found that T cell-specific knockout mice are immunocompromised and less capable of controlling infection with influenza A. This is likely due to a decrease in thymocyte numbers, as well as mature peripheral T cells. The authors also reported that SOD2−/− thymocytes displayed drastic changes in metabolism, increased numbers of dysfunctional mitochondria, and increased mitophagy. Importantly, immunocompetence was largely restored through treatment with a mitochondria-targeted SOD mimetic, nitroxide, which, similar to SOD, produces H2O2 from O2•−.

Too much SOD2, still a big problem

Several clinical studies have reported over the years that advanced, high-grade tumors are generally characterized by high levels of SOD2 expression, strongly contrasting with the concept that SOD2 is a tumor suppressor (22, 33, 52, 60, 112). More detailed analyses reveal that although SOD2 levels are reduced in pre-cancerous lesions, its expression steadily climbs as tumors transition to more malignant states (33). These observations suggest an important adjustment to the classical view of this enzyme's role in cancer. Although SOD2 may be a suppressor of tumor initiation, it is actually capable of promoting tumor progression toward more malignant phenotypes once the disease is established.

In 2013, our group described a peroxidase activity for SOD2, which we only detected when SOD2 was overexpressed in breast cancer cell lines (4). This peroxidase activity was the first alternative function reported for SOD2, and it differed substantially from the classic antioxidant activity. Metal-dependent peroxidases normally function as activators of H2O2-dependent one-electron oxidations. Since H2O2 is the product of SOD2's dismutase activity, the presence of even a small subset of SOD2 molecules with peroxidase activity could functionally convert SOD2 into a powerful pro-oxidant system. In this model, SOD2's canonical dismutase activity would yield H2O2 that could promote SOD2's noncanonical peroxidase activity, and this would, in turn, drive oxidative reactions in mitochondria. Progress has been made in understanding the molecular mechanisms underpinning this peroxidase activity, as well. More recent work has determined that under conditions where SOD2 is expressed at greater than physiological levels, or where manganese is deficient, SOD2 incorporates iron instead. The incorporation of iron in lieu of manganese simultaneously ablates the SOD activity and enables SOD2 to function as a peroxidase using H2O2 to oxidize a diverse array of substrates (43, 44). It is perhaps not surprising to find that a well-conserved, essential enzyme such as SOD2 does not serve a single function. Instead, the evidence paints a picture of SOD2 as a complex and finely regulated signaling node, influencing cell behavior to ingrate metabolic and non-metabolic information from the mitochondrion with the rest of the cell. It is possible that yet more activities and roles may be uncovered for SOD2, which brings us to some of the more unusual observations surrounding this intriguing enzyme.

SOD2: The Unusual and the Intriguing

Having discussed some of the established aspects of SOD2 biology and introduced some of the new emerging concepts, this section will review some of the most intriguing findings involving SOD2. The observation of high levels of SOD2 expression in tumors was unexpected from the perspective of SOD2 as a tumor suppressor. However, this apparent paradox led to the detection of a number of PTMs that, in turn, enabled the discovery of alternative activities and modes of redox regulation for other signaling molecules that were previously unknown. Studies from our own laboratory found that during tumor progression, an increase in SOD2 expression activates 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). This key metabolic enzyme responds to energetic deficits in cells by promoting glycolysis (52), and so its aberrant activation could have a role in tumor progression. Usually, AMPK serves as a positive regulator of phosphofructokinase-2 (PFK2), a rate-limiting step in the activation of glycolysis (2), but ATP allosterically inhibits AMPK and suppresses glycolytic metabolism via the AMPK/PFK2 axis. Thus, when mitochondria are working at high energetic efficiency, glycolysis is inhibited because of the suppressive allosteric effects of ATP on AMPK and other enzymes in the glycolytic pathway. Pyruvate is the three-carbon terminal product of glycolysis. It fuels the tricarboxylic acid cycle, which generates much of the FADH2 and NADH that drive ATP production by the ETC. Pyruvate entrance into the Kreb's cycle regulates how much ATP the ETC produces, and ETC-derived ATP controls how much glucose is broken down into pyruvate. Therefore, ATP and pyruvate compose a double switch system that regulates the rate of glucose breakdown, which is directly regulated by AMPK. SOD2, however, can disrupt this finely balanced system. SOD2 upregulation in cancer cells leads to an increase in mitochondrial H2O2, which, in turn, oxidizes calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), a direct positive regulator of AMPK (52). This has the effect of overriding the inhibition of AMPK by ATP. In principle, this would allow glycolysis to work at maximal capacity uninhibited by mitochondrially generated ATP, even if mitochondria perform at high efficiency. Interestingly, metastatic cancer cells reactivate their mitochondrial respiration and mitochondrial ATP production without reducing their glycolytic rates (67). Though a role for the SOD2/CaMKII/AMPK axis has yet to be demonstrated in metastasis, this would be in line with observations of increased SOD2 expression and metabolism in metastatic cells. Also consistent with this, it was recently shown that the number of foci high in SOD2 in primary breast cancers is positively correlated with the risk of metastasis, suggesting that high SOD2 expression is a feature of metastatic breast cancer cells phenotypes (60). It has also been shown that SOD2 directly suppresses the expression of the well-established tumor suppressor, p53, and p53, in turn, suppresses SOD2 as well (34). In fact, SOD2 has been found as part of a complex with p53 and polγ in the mitochondria of ultraviolet B irradiated cells, indicating that it may have a role in mitochondrial DNA repair. Though the interpretation of this result was that SOD2 provides protection for polγ against oxidative damage, a direct role for SOD2 in the formation or stabilization of the complex cannot be excluded based on the data (6). As results like those discussed earlier accumulate, it is increasingly clear that the role of SOD2 in the cellular physiology extends well beyond that of a mitochondrial antioxidant or classic tumor suppressor.

Conclusion

It is undeniable that SOD2 acts as a dismutase of superoxide, and this protects select biomolecules in mitochondria from oxidative modifications under specific conditions. The evidence reviewed here, however, indicates that the antioxidant function associated with the dismutase activity is only one aspect of SOD2 biology, and that the enzyme almost certainly possesses other critical roles in the cell as a central regulator of redox signaling. The thinking surrounding ROS has evolved considerably in the past few decades. Although these chemical species were once largely considered agents of damage to normal cellular and physiological processes, they have taken center stage now as critical messengers for signal transduction, conveying a dizzying array of intra- and inter-cellular information. In retrospect, these highly reactive species have ideal chemical properties for propagating information through many types of biological media. Nonetheless, the enzymes that regulate their production, diffusion, reactivity, and inter-conversion have been widely viewed as protective to cells and physiology by acting as antioxidants. Data are accumulating, however, that indicate it is time for the thinking around the enzymes that regulate ROS to undergo their own rehabilitation. It may be that the canonical antioxidant role of SOD2 is the primary function of this enzyme when superoxide radical levels surpass the signaling threshold, and begin to threaten cellular viability through indiscriminate damage or irreversible protein modifications. However, since it is now clear that ROS are not exclusively deleterious, it is likely that the machinery that regulates their biology is also not exclusively protective. Rather, a picture is emerging of these enzymes as shaping the landscape of oxidant signaling networks, enabling precise communications between organelles and cells. SOD2 is an enzyme that in isolation does not have an antioxidant function, and it has already been shown to engage in multiple regulatory mechanisms. These studies serve as the basis for a new model of SOD2 function that extends far beyond mitigating oxidative injury in mitochondria. Whether converting superoxide from the ETC into H2O2 signals that broadcast the status of mitochondrial metabolism to other parts of the cell, serving structural or stabilizing roles in multiprotein complexes, or regulating mitochondrial quality control, it seems unavoidable that a multitude of new roles and activities are destined to be discovered. The ubiquity of these functions in regulating physiological and pathophysiological processes make SOD2 very attractive for novel therapeutic interventions to target mitochondria and redox signaling.

Abbreviations Used

- Aco2

aconitase 2

- AMPK

5′ AMP-activated protein kinase

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- CAMKII

calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- ETC

electron transport chain

- FADH2

flavine adenine dinucleotide, reduced

- FeSOD2

iron-dependent superoxide dismutase

- GPX

glutathione peroxidase

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- MnSOD

manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase

- NADH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, reduced

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, reduced

- •NO

nitric oxide

- O2•−

superoxide radical

- ONOO−

peroxynitrite

- PFK2

phosphofructokinase-2

- PRDX

peroxiredoxin

- PTM

post-translational modification

- PTP

protein tyrosine phosphatase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SDH

succinate dehydrogenase

- SDHD

succinate dehydrogenase subunit D

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- SOD2

mitochondrial superoxide dismutase

- VDAC

voltage-dependent anion-selective channel

Funding Information

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the United States National Institutes of Health: RO1AI131267 (to M.G.B.); RO1CA216882 (to M.G.B.); RO1ES028149 (to M.G.B.); and RO1HL125356 (to M.G.B) and the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment to M.G.B. and B.N.G.

References

- 1. Abela L, Spiegel R, Crowther LM, Klein A, Steindl K, Papuc SM, Joset P, Zehavi Y, Rauch A, Plecko B, and Simmons TL. Plasma metabolomics reveals a diagnostic metabolic fingerprint for mitochondrial aconitase (ACO2) deficiency. PLoS One 12: e0176363, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Almeida A, Moncada S, and Bolanos JP. Nitric oxide switches on glycolysis through the AMP protein kinase and 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase pathway. Nat Cell Biol 6: 45–51, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson RF. The reactions of oxygen and superoxide ions with flavosemiquinone radicals. In: Oxygen and Oxy-Radicals in Chemistry and Biology, edited by Rodgers MAJ, and Powers EL. New York, NY: Academic Press; pp. 597–600, 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ansenberger-Fricano K, Ganini D, Mao M, Chatterjee S, Dallas S, Mason RP, Stadler K, Santos JH, and Bonini MG. The peroxidase activity of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase. Free Radic Biol Med 54: 116–124, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Asada K, Takahashi MA, Tanaka K, and Nakando Y. Formation of active oxygen and its fate in chloroplast. In: Biochemical and Medical Aspects of Active Oxygen, edited by Hayaishi O and Asada K. Baltimore, MD: University Park Press, 1977, pp. 45–63 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bakthavatchalu V, Dey S, Xu Y, Noel T, Jungsuwadee P, Holley AK, Dhar SK, Batinic-Haberle I, and St Clair DK. Manganese superoxide dismutase is a mitochondrial fidelity protein that protects Polgamma against UV-induced inactivation. Oncogene 31: 2129–2139, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Batinic-Haberle I, Tovmasyan A, and Spasojevic I. An educational overview of the chemistry, biochemistry and therapeutic aspects of Mn porphyrins—from superoxide dismutation to H2O2-driven pathways. Redox Biol 5: 43–65, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, Marshall PA, and Freeman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87: 1620–1624, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bedard K and Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 87: 245–313, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bell EL, Klimova TA, Eisenbart J, Moraes CT, Murphy MP, Budinger GR, and Chandel NS. The Qo site of the mitochondrial complex III is required for the transduction of hypoxic signaling via reactive oxygen species production. J Cell Biol 177: 1029–1036, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bielski BHJ and Allen AO. Mechanism of the disproportionation of superoxide radicals. J Phys Chem 81: 1048–1050, 1977 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boedtkjer E and Aalkjaer C. Insulin inhibits Na+/H+ exchange in vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells in situ: involvement of H2O2 and tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H247–H255, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bogeski I, Bozem M, Sternfeld L, Hofer HW, and Schulz I. Inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B by reactive oxygen species leads to maintenance of Ca2+ influx following store depletion in HEK 293 cells. Cell Calcium 40: 1–10, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bombicino SS, Iglesias DE, Rukavina-Mikusic IA, Buchholz B, Gelpi RJ, Boveris A, and Valdez LB. Hydrogen peroxide, nitric oxide and ATP are molecules involved in cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis in diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med 112: 267–276, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bonini MG, Rota C, Tomasi A, and Mason RP. The oxidation of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin to reactive oxygen species: a self-fulfilling prophesy? Free Radic Biol Med 40: 968–975, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Buettner GR. The pecking order of free radicals and antioxidants: lipid peroxidation, alpha-tocopherol, and ascorbate. Arch Biochem Biophys 300: 535–543, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bull C, Niederhoffer EC, Yoshida T, and Fee JA. Kinetic studies of superoxide dismutases: properties of the manganese-containing protein from Thermus thermophilus. J Am Chem Soc 113: 4069–4076, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bulteau AL, Szweda LI, and Friguet B. Mitochondrial protein oxidation and degradation in response to oxidative stress and aging. Exp Gerontol 41: 653–657, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Case AJ and Domann FE. Manganese superoxide dismutase is dispensable for post-natal development and lactation in the murine mammary gland. Free Radic Res 46: 1361–1368, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Case AJ, McGill JL, Tygrett LT, Shirasawa T, Spitz DR, Waldschmidt TJ, Legge KL, and Domann FE. Elevated mitochondrial superoxide disrupts normal T cell development, impairing adaptive immune responses to an influenza challenge. Free Radic Biol Med 50: 448–458, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chandel NS, McClintock DS, Feliciano CE, Wood TM, Melendez JA, Rodriguez AM, and Schumacker PT. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. J Biol Chem 275: 25130–25138, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chang B, Yang H, Jiao Y, Wang K, Liu Z, Wu P, Li S, and Wang A. SOD2 deregulation enhances migration, invasion and has poor prognosis in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Sci Rep 6: 25918, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen Y, Zhang J, Lin Y, Lei Q, Guan KL, Zhao S, and Xiong Y. Tumour suppressor SIRT3 deacetylates and activates manganese superoxide dismutase to scavenge ROS. EMBO Rep 12: 534–541, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chouchani ET, Pell VR, James AM, Work LM, Saeb-Parsy K, Frezza C, Krieg T, and Murphy MP. A unifying mechanism for mitochondrial superoxide production during ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Metab 23: 254–263, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cid-Castro C, Hernandez-Espinosa DR, and Moran J. ROS as regulators of mitochondrial dynamics in neurons. Cell Mol Neurobiol 38: 995–1007, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coloff JL, Murphy JP, Braun CR, Harris IS, Shelton LM, Kami K, Gygi SP, Selfors LM, and Brugge JS. Differential glutamate metabolism in proliferating and quiescent mammary epithelial cells. Cell Metab 23: 867–880, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Connor KM, Subbaram S, Regan KJ, Nelson KK, Mazurkiewicz JE, Bartholomew PJ, Aplin AE, Tai YT, Aguirre-Ghiso J, Flores SC, and Melendez JA. Mitochondrial H2O2 regulates the angiogenic phenotype via PTEN oxidation. J Biol Chem 280: 16916–16924, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cox AG, Winterbourn CC, and Hampton MB. Mitochondrial peroxiredoxin involvement in antioxidant defence and redox signalling. Biochem J 425: 313–325, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Culotta VC, Yang M, and O'Halloran TV. Activation of superoxide dismutases: putting the metal to the pedal. Biochim Biophys Acta 1763: 747–758, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cunnick JM, Dorsey JF, Mei L, and Wu J. Reversible regulation of SHP-1 tyrosine phosphatase activity by oxidation. Biochem Mol Biol Int 45: 887–894, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cyr AR, Brown KE, McCormick ML, Coleman MC, Case AJ, Watts GS, Futscher BW, Spitz DR, and Domann FE. Maintenance of mitochondrial genomic integrity in the absence of manganese superoxide dismutase in mouse liver hepatocytes. Redox Biol 1: 172–177, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Darby Weydert CJ, Smith BB, Xu L, Kregel KC, Ritchie JM, Davis CS, and Oberley LW. Inhibition of oral cancer cell growth by adenovirusMnSOD plus BCNU treatment. Free Radic Biol Med 34: 316–329, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dhar SK, Tangpong J, Chaiswing L, Oberley TD, and St Clair DK. Manganese superoxide dismutase is a p53-regulated gene that switches cancers between early and advanced stages. Cancer Res 71: 6684–6695, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Drane P, Bravard A, Bouvard V, and May E. Reciprocal down-regulation of p53 and SOD2 gene expression-implication in p53 mediated apoptosis. Oncogene 20: 430–439, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dyall SD, Brown MT, and Johnson PJ. Ancient invasions: from endosymbionts to organelles. Science 304: 253–257, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ekoue DN, He C, Diamond AM, and Bonini MG. Manganese superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase-1 contribute to the rise and fall of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species which drive oncogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1858: 628–632, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Emerling BM, Platanias LC, Black E, Nebreda AR, Davis RJ, and Chandel NS. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for hypoxia signaling. Mol Cell Biol 25: 4853–4862, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Figueira TR, Barros MH, Camargo AA, Castilho RF, Ferreira JC, Kowaltowski AJ, Sluse FE, Souza-Pinto NC, and Vercesi AE. Mitochondria as a source of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: from molecular mechanisms to human health. Antioxid Redox Signal 18: 2029–2074, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Flint DH, Tuminello JF, and Emptage MH. The inactivation of Fe-S cluster containing hydro-lyases by superoxide. J Biol Chem 268: 22369–22376, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Forman HJ and Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase: a comparison of rate constants. Arch Biochem Biophys 158: 396–400, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Forman HJ, Augusto O, Brigelius-Flohe R, Dennery PA, Kalyanaraman B, Ischiropoulos H, Mann GE, Radi R, Roberts LJ, Vina J 2nd, and Davies KJ. Even free radicals should follow some rules: a guide to free radical research terminology and methodology. Free Radic Biol Med 78: 233–235, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fukai T and Ushio-Fukai M. Superoxide dismutases: role in redox signaling, vascular function, and diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 1583–1606, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ganini D, Petrovich RM, Edwards LL, and Mason RP. Iron incorporation into MnSOD A (bacterial Mn-dependent superoxide dismutase) leads to the formation of a peroxidase/catalase implicated in oxidative damage to bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta 1850: 1795–1805, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ganini D, Santos JH, Bonini MG, and Mason RP. Switch of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase into a prooxidant peroxidase in manganese-deficient cells and mice. Cell Chem Biol 25: 413–425.6, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gardner PR and Fridovich I. Superoxide sensitivity of the Escherichia coli 6-phosphogluconate dehydratase. J Biol Chem 266: 1478–1483, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gardner PR and Fridovich I. Superoxide sensitivity of the Escherichia coli aconitase. J Biol Chem 266: 19328–19333, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gardner PR and Fridovich I. Inactivation-reactivation of aconitase in Escherichia coli. A sensitive measure of superoxide radical. J Biol Chem 267: 8757–8763, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gutteridge JM and Halliwell B. Free radicals and antioxidants in the year 2000. A historical look to the future. Ann N Y Acad Sci 899: 136–147, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Guzy RD and Schumacker PT. Oxygen sensing by mitochondria at complex III: the paradox of increased reactive oxygen species during hypoxia. Exp Physiol 91: 807–819, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Halliwell B and Gutteridge J. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine, 4th ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hao HX, Khalimonchuk O, Schraders M, Dephoure N, Bayley JP, Kunst H, Devilee P, Cremers CW, Schiffman JD, Bentz BG, Gygi SP, Winge DR, Kremer H, and Rutter J. SDH5, a gene required for flavination of succinate dehydrogenase, is mutated in paraganglioma. Science 325: 1139–1142, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hart PC, Mao M, de Abreu AL, Ansenberger-Fricano K, Ekoue DN, Ganini D, Kajdacsy-Balla A, Diamond AM, Minshall RD, Consolaro ME, Santos JH, and Bonini MG. MnSOD upregulation sustains the Warburg effect via mitochondrial ROS and AMPK-dependent signalling in cancer. Nat Commun 6: 6053, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hemachandra LP, Shin DH, Dier U, Iuliano JN, Engelberth SA, Uusitalo LM, Murphy SK, and Hempel N. Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase has a protumorigenic role in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 75: 4973–4984, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hempel N, Ye H, Abessi B, Mian B, and Melendez JA. Altered redox status accompanies progression to metastatic human bladder cancer. Free Radic Biol Med 46: 42–50, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Huang JY, Schwer B, and Verdin E. SIRT3 regulates mitochondrial protein acetylation and intermediary metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 76: 267–277, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Imlay JA. Iron-sulphur clusters and the problem with oxygen. Mol Microbiol 59: 1073–1082, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jin C, Qin L, Shi Y, Candas D, Fan M, Lu CL, Vaughan AT, Shen R, Wu LS, Liu R, Li RF, Murley JS, Woloschak G, Grdina DJ, and Li JJ. CDK4-mediated MnSOD activation and mitochondrial homeostasis in radioadaptive protection. Free Radic Biol Med 81: 77–87, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jones MK, Zhu E, Sarino EV, Padilla OR, Takahashi T, Shimizu T, and Shirasawa T. Loss of parietal cell superoxide dismutase leads to gastric oxidative stress and increased injury susceptibility in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 301: G537–G546, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Keele BB Jr McCord JM, and Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase from Escherichia coli B. A new manganese-containing enzyme. J Biol Chem 245: 6176–6181, 1970 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kenny TC, Hart P, Ragazzi M, Sersinghe M, Chipuk J, Sagar MAK, Eliceiri KW, LaFramboise T, Grandhi S, Santos J, Riar AK, Papa L, D'Aurello M, Manfredi G, Bonini MG, and Germain D. Selected mitochondrial DNA landscapes activate the SIRT3 axis of the UPR(mt) to promote metastasis. Oncogene 36: 4393–4404, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kim JJ, Chae SW, Hur GC, Cho SJ, Kim MK, Choi J, Nam SY, Kim WH, Yang HK, and Lee BL. Manganese superoxide dismutase expression correlates with a poor prognosis in gastric cancer. Pathobiology 70: 353–360, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kim YM, Youn SW, Sudhahar V, Das A, Chandhri R, Cuervo Grajal H, Kweon J, Leanhart S, He L, Toth PT, Kitajewski J, Rehman J, Yoon Y, Cho J, Fukai T, and Ushio-Fukai M. Redox regulation of mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 by protein disulfide isomerase limits endothelial senescence. Cell Rep 23: 3565–3578, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kono Y and Fridovich I. Superoxide radical inhibits catalase. J Biol Chem 257: 5751–5754, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Krebs HA. The citric acid cycle and the Szent-Gyorgyi cycle in pigeon breast muscle. Biochem J 34: 775–779, 1940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kujoth GC, Hiona A, Pugh TD, Someya S, Panzer K, Wohlgemuth SE, Hofer T, Seo AY, Sullivan R, Jobling WA, Morrow JD, Van Remmen H, Sedivy JM, Yamasoba T, Tanokura M, Weindruch R, Leeuwenburgh C, and Prolla TA. Mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science 309: 481–484, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kuo CF, Mashino T, and Fridovich I. Alpha, beta-dihydroxyisovalerate dehydratase. A superoxide-sensitive enzyme. J Biol Chem 262: 4724–4727, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. LeBleu VS, O'Connell JT, Gonzalez Herrera KN, Wikman H, Pantel K, Haigis MC, de Carvalho FM, Damascena A, Domingos Chinen LT, Rocha RM, Asara JM, and Kalluri R. PGC-1α mediates mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation in cancer cells to promote metastasis. Nat Cell Biol 16: 992, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lenart J, Dombrowski F, Gorlach A, and Kietzmann T. Deficiency of manganese superoxide dismutase in hepatocytes disrupts zonated gene expression in mouse liver. Arch Biochem Biophys 462: 238–244, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Li Y, Huang TT, Carlson EJ, Melov S, Ursell PC, Olson JL, Noble LJ, Yoshimura MP, Berger C, Chan PH, Wallace DC, and Epstein CJ. Dilated cardiomyopathy and neonatal lethality in mutant mice lacking manganese superoxide dismutase. Nat Genet 11: 376–381, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Liang LP and Patel M. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and increased seizure susceptibility in Sod2(−/+) mice. Free Radic Biol Med 36: 542–554, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Liochev SI and Fridovich I. Fumarase C, the stable fumarase of Escherichia coli, is controlled by the soxRS regulon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89: 5892–5896, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Loschen G and Azzi A. On the formation of hydrogen peroxide and oxygen radicals in heart mitochondria. Recent Adv Stud Cardiac Struct Metab 7: 3–12, 1975 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lustgarten MS, Bhattacharya A, Muller FL, Jang YC, Shimizu T, Shirasawa T, Richardson A, and Van Remmen H. Complex I generated, mitochondrial matrix-directed superoxide is released from the mitochondria through voltage dependent anion channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 422: 515–521, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mal A and Chatterjee IB. Mechanism of autoxidation of oxyhaemoglobin. J Biosci 16: 55–70, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 75. Marine A, Krager KJ, Aykin-Burns N, and Macmillan-Crow LA. Peroxynitrite induced mitochondrial biogenesis following MnSOD knockdown in normal rat kidney (NRK) cells. Redox Biol 2: 348–357, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Martinez-Reyes I, Diebold LP, Kong H, Schieber M, Huang H, Hensley CT, Mehta MM, Wang T, Santos JH, Woychik R, Dufour E, Spelbrink JN, Weinberg SE, Zhao Y, DeBerardinis RJ, and Chandel NS. TCA cycle and mitochondrial membrane potential are necessary for diverse biological functions. Mol Cell 61: 199–209, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Meng TC, Buckley DA, Galic S, Tiganis T, and Tonks NK. Regulation of insulin signaling through reversible oxidation of the protein-tyrosine phosphatases TC45 and PTP1B. J Biol Chem 279: 37716–37725, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Miar A, Hevia D, Munoz-Cimadevilla H, Astudillo A, Velasco J, Sainz RM, and Mayo JC. Manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2/MnSOD)/catalase and SOD2/GPx1 ratios as biomarkers for tumor progression and metastasis in prostate, colon, and lung cancer. Free Radic Biol Med 85: 45–55, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Miguel F, Augusto AC, and Gurgueira SA. Effect of acute vs chronic H2O2-induced oxidative stress on antioxidant enzyme activities. Free Radic Res 43: 340–347, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Missirlis F, Hu J, Kirby K, Hilliker AJ, Rouault TA, and Phillips JP. Compartment-specific protection of iron-sulfur proteins by superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem 278: 47365–47369, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Moreno-Sanchez R, Marin-Hernandez A, Gallardo-Perez JC, Vazquez C, Rodriguez-Enriquez S, and Saavedra E. Control of the NADPH supply and GSH recycling for oxidative stress management in hepatoma and liver mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1859: 1138–1150, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Munro D, Banh S, Sotiri E, Tamanna N, and Treberg JR. The thioredoxin and glutathione-dependent H2O2 consumption pathways in muscle mitochondria: involvement in H2O2 metabolism and consequence to H2O2 efflux assays. Free Radic Biol Med 96: 334–346, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Netto LE and Antunes F. The roles of peroxiredoxin and thioredoxin in hydrogen peroxide sensing and in signal transduction. Mol Cells 39: 65–71, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Nguyen D, Samson SL, Reddy VT, Gonzalez EV, and Sekhar RV. Impaired mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and insulin resistance in aging: novel protective role of glutathione. Aging Cell 12: 415–425, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Oh SS, Sullivan KA, Wilkinson JE, Backus C, Hayes JM, Sakowski SA, and Feldman EL. Neurodegeneration and early lethality in superoxide dismutase 2-deficient mice: a comprehensive analysis of the central and peripheral nervous systems. Neuroscience 212: 201–213, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Okado-Matsumoto A and Fridovich I. Assay of superoxide dismutase: cautions relevant to the use of cytochrome c, a sulfonated tetrazolium, and cyanide. Anal Biochem 298: 337–342, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Okado-Matsumoto A and Fridovich I. Subcellular distribution of superoxide dismutases (SOD) in rat liver: Cu,Zn-SOD in mitochondria. J Biol Chem 276: 38388–38393, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ortega SP, Chouchani ET, and Boudina S. Stress turns on the heat: regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and UCP1 by ROS in adipocytes. Adipocyte 6: 56–61, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ough M, Lewis A, Zhang Y, Hinkhouse MM, Ritchie JM, Oberley LW, and Cullen JJ. Inhibition of cell growth by overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) in human pancreatic carcinoma. Free Radic Res 38: 1223–1233, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Pani G, Koch OR, and Galeotti T. The p53-p66shc-Manganese Superoxide Dismutase (MnSOD) network: a mitochondrial intrigue to generate reactive oxygen species. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41: 1002–1005, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Parajuli N, Marine A, Simmons S, Saba H, Mitchell T, Shimizu T, Shirasawa T, and Macmillan-Crow LA. Generation and characterization of a novel kidney-specific manganese superoxide dismutase knockout mouse. Free Radic Biol Med 51: 406–416, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Piruat JI, Pintado CO, Ortega-Saenz P, Roche M, and Lopez-Barneo J. The mitochondrial SDHD gene is required for early embryogenesis, and its partial deficiency results in persistent carotid body glomus cell activation with full responsiveness to hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol 24: 10933–10940, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Pollard PJ, Briere JJ, Alam NA, Barwell J, Barclay E, Wortham NC, Hunt T, Mitchell M, Olpin S, Moat SJ, Hargreaves IP, Heales SJ, Chung YL, Griffiths JR, Dalgleish A, McGrath JA, Gleeson MJ, Hodgson SV, Poulsom R, Rustin P, and Tomlinson IP. Accumulation of Krebs cycle intermediates and over-expression of HIF1alpha in tumours which result from germline FH and SDH mutations. Hum Mol Genet 14: 2231–2239, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Pontieri P, De Stefano M, Massardo DR, Gunge N, Miyakawa I, Sando N, Pignone D, Pizzolante G, Romano R, Alifano P, and Del Giudice L. Tellurium as a valuable tool for studying the prokaryotic origins of mitochondria. Gene 559: 177–183, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Poole LB, Hall A, and Nelson KJ.. Overview of peroxiredoxins in oxidant defense and redox regulation. Curr Protoc Toxicol Chapter 7, Unit7.9, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Porcelli AM, Ghelli A, Zanna C, Pinton P, Rizzuto R, and Rugolo M. pH difference across the outer mitochondrial membrane measured with a green fluorescent protein mutant. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 326: 799–804, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Powell CS and Jackson RM. Mitochondrial complex I, aconitase, and succinate dehydrogenase during hypoxia-reoxygenation: modulation of enzyme activities by MnSOD. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 285: L189–L198, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Qiu X, Brown K, Hirschey MD, Verdin E, and Chen D. Calorie restriction reduces oxidative stress by SIRT3-mediated SOD2 activation. Cell Metab 12: 662–667, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Quiros I, Sainz RM, Hevia D, Garcia-Suarez O, Astudillo A, Rivas M, and Mayo JC. Upregulation of manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2) is a common pathway for neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer 125: 1497–1504, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Radi R. Oxygen radicals, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite: redox pathways in molecular medicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115: 5839–5848, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Reczek CR and Chandel NS. ROS-dependent signal transduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol 33: 8–13, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Rhee SG, Woo HA, and Kang D. The role of peroxiredoxins in the transduction of H2O2 signals. Antioxid Redox Signal 28: 537–557, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Robb EL, Hall AR, Prime TA, Eaton S, Szibor M, Viscomi C, James AM, and Murphy MP. Control of mitochondrial superoxide production by reverse electron transport at complex I. J Biol Chem 293: 9869–9879, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Sakellariou GK, Pearson T, Lightfoot AP, Nye GA, Wells N, Giakoumaki II, Vasilaki A, Griffiths RD, Jackson MJ, and McArdle A. Mitochondrial ROS regulate oxidative damage and mitophagy but not age-related muscle fiber atrophy. Sci Rep 6: 33944, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Sarsour EH, Kalen AL, Xiao Z, Veenstra TD, Chaudhuri L, Venkataraman S, Reigan P, Buettner GR, and Goswami PC. Manganese superoxide dismutase regulates a metabolic switch during the mammalian cell cycle. Cancer Res 72: 3807–3816, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Saxena N, Maio N, Crooks DR, Ricketts CJ, Yang Y, Wei MH, Fan TW, Lane AN, Sourbier C, Singh A, Killian JK, Meltzer PS, Vocke CD, Rouault TA, and Linehan WM. SDHB-deficient cancers: the role of mutations that impair iron sulfur cluster delivery. J Natl Cancer Inst 108: djv287, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Schriner SE, Linford NJ, Martin GM, Treuting P, Ogburn CE, Emond M, Coskun PE, Ladiges W, Wolf N, Van Remmen H, Wallace DC, and Rabinovitch PS. Extension of murine life span by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Science 308: 1909–1911, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Selak MA, Armour SM, MacKenzie ED, Boulahbel H, Watson DG, Mansfield KD, Pan Y, Simon MC, Thompson CB, and Gottlieb E. Succinate links TCA cycle dysfunction to oncogenesis by inhibiting HIF-alpha prolyl hydroxylase. Cancer Cell 7: 77–85, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Shchepinova MM, Cairns AG, Prime TA, Logan A, James AM, Hall AR, Vidoni S, Arndt S, Caldwell ST, Prag HA, Pell VR, Krieg T, Mulvey JF, Yadav P, Cobley JN, Bright TP, Senn HM, Anderson RF, Murphy MP, and Hartley RC. MitoNeoD: a mitochondria-targeted superoxide probe. Cell Chem Biol 24: 1285–1298.e12, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Sheng Y, Abreu IA, Cabelli DE, Maroney MJ, Miller AF, Teixeira M, and Valentine JS. Superoxide dismutases and superoxide reductases. Chem Rev 114: 3854–3918, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Smith IN and Briggs JM. Structural mutation analysis of PTEN and its genotype-phenotype correlations in endometriosis and cancer. Proteins 84: 1625–1643, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Sotgia F, Fiorillo M, and Lisanti MP. Mitochondrial markers predict recurrence, metastasis and tamoxifen-resistance in breast cancer patients: early detection of treatment failure with companion diagnostics. Oncotarget 8: 68730–68745, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Tao R, Coleman MC, Pennington JD, Ozden O, Park SH, Jiang H, Kim HS, Flynn CR, Hill S, Hayes McDonald W, Olivier AK, Spitz DR, and Gius D. Sirt3-mediated deacetylation of evolutionarily conserved lysine 122 regulates MnSOD activity in response to stress. Mol Cell 40: 893–904, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Tao R, Vassilopoulos A, Parisiadou L, Yan Y, and Gius D. Regulation of MnSOD enzymatic activity by Sirt3 connects the mitochondrial acetylome signaling networks to aging and carcinogenesis. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 1646–1654, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Thornalley PJ and Vašák M. Possible role for metallothionein in protection against radiation-induced oxidative stress. Kinetics and mechanism of its reaction with superoxide and hydroxyl radicals. Mol Enzymol 827: 36–44, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Tong WH, Sourbier C, Kovtunovych G, Jeong SY, Vira M, Ghosh M, Romero VV, Sougrat R, Vaulont S, Viollet B, Kim YS, Lee S, Trepel J, Srinivasan R, Bratslavsky G, Yang Y, Linehan WM, and Rouault TA. The glycolytic shift in fumarate-hydratase-deficient kidney cancer lowers AMPK levels, increases anabolic propensities and lowers cellular iron levels. Cancer Cell 20: 315–327, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Tormos KV, Anso E, Hamanaka RB, Eisenbart J, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B, and Chandel NS. Mitochondrial complex III ROS regulate adipocyte differentiation. Cell Metab 14: 537–544, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Trewin AJ, Berry BJ, and Wojtovich AP. Exercise and mitochondrial dynamics: keeping in shape with ROS and AMPK. Antioxidants (Basel) 7: pii:, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Ueda S, Masutani H, Nakamura H, Tanaka T, Ueno M, and Yodoi J. Redox control of cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal 4: 405–414, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Ugarte N, Petropoulos I, and Friguet B. Oxidized mitochondrial protein degradation and repair in aging and oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal 13: 539–549, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Van Remmen H, Williams MD, Guo Z, Estlack L, Yang H, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Huang TT, and Richardson A. Knockout mice heterozygous for Sod2 show alterations in cardiac mitochondrial function and apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H1422–H1432, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Verniquet F, Gaillard J, Neuburger M, and Douce R. Rapid inactivation of plant aconitase by hydrogen peroxide. Biochem J 276 (Pt 3): 643–648, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Waypa GB, Marks JD, Guzy RD, Mungai PT, Schriewer JM, Dokic D, Ball MK, and Schumacker PT. Superoxide generated at mitochondrial complex III triggers acute responses to hypoxia in the pulmonary circulation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187: 424–432, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Weisiger RA and Fridovich I. Mitochondrial superoxide simutase. Site of synthesis and intramitochondrial localization. J Biol Chem 248: 4793–4796, 1973 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Weisiger RA and Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase. Organelle specificity. J Biol Chem 248: 3582–3592, 1973 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Wicks SE, Vandanmagsar B, Haynie KR, Fuller SE, Warfel JD, Stephens JM, Wang M, Han X, Zhang J, Noland RC, and Mynatt RL. Impaired mitochondrial fat oxidation induces adaptive remodeling of muscle metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: E3300–E3309, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Williams MD, Van Remmen H, Conrad CC, Huang TT, Epstein CJ, and Richardson A. Increased oxidative damage is correlated to altered mitochondrial function in heterozygous manganese superoxide dismutase knockout mice. J Biol Chem 273: 28510–28515, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]