Abstract

A lack of gravity experienced during space flight has been shown to have profound effects on human physiology including muscle atrophy, reductions in bone density and immune function, and endocrine disorders. At present, these physiological changes present major obstacles to long-term space missions. What is not clear is which pathophysiological disruptions reflect changes at the cellular level versus changes that occur due to the impact of weightlessness on the entire body. This review focuses on current research investigating the impact of microgravity at the cellular level including cellular morphology, proliferation, and adhesion. As direct research in space is currently cost prohibitive, we describe here the use of microgravity simulators for studies at the cellular level. Such instruments provide valuable tools for cost-effective research to better discern the impact of weightlessness on cellular function. Despite recent advances in understanding the relationship between extracellular forces and cell behavior, very little is understood about cellular biology and mechanotransduction under microgravity conditions. This review will examine recent insights into the impact of simulated microgravity on cell biology and how this technology may provide new insight into advancing our understanding of mechanically driven biology and disease.

Keywords: microgravity, mechanobiology, mechanotransduction, cytoskeletal, mechanosensing

Introduction

Humans are subjected to persistent gravitational force and the importance of gravity for maintaining physiological function has been revealed by the detrimental impacts of space travel on human health. During space flight, astronauts are exposed to a prolonged state of microgravity and develop a myriad of physiological disruptions including a loss of muscle mass and bone density, impaired vision, decreased kidney function, diminished neurological responses, and a compromised immune system (White and Averner, 2001; Horneck et al., 2003; Crucian et al., 2014; White et al., 2016). This review will discuss recent data that highlight the impact of microgravity at the cellular level. Additionally, this review addresses how such research can be conducted on earth by simulating the microgravity state. These studies are not only important for understanding how humans are affected by microgravity but have the potential to elucidate the role of mechanical stimuli on cellular function and the development of mechanically driven disease states.

Mechanobiology is the study of how cells are influenced by their physical environment. This emerging field of research provides an important perspective on understanding many aspects of cellular function and dysfunction. Cells can convert mechanical inputs into biochemical signals to initiate downstream signaling cascades in process known as mechanotransduction. Gravitational force is presumed to play a crucial role in regulating cell and tissue homeostasis by inducing mechanical stresses experienced at the cellular level. Thus, the concept of mechanical unloading (a decrease in mechanical stress) is associated with the weightlessness of space and can be replicated by simulating microgravity conditions, allowing for investigation of the mechanobiology aspects of cell function. The mechanical unloading of cells under microgravity conditions shifts the balance between physiology and pathophysiology, accelerating the progression and development of some disease states. For example, kidney stone formation is accelerated under microgravity conditions compared to Earth’s gravity (1 g) (Pavlakou et al., 2018). Similarly, osteoporosis can take decades to develop under normal gravitational loading, yet this disease can be modeled under microgravity over shorter time scales (Pajevic et al., 2013). The mechanisms by which human physiology are disrupted in microgravity remain unknown, rendering numerous open questions regarding the adaptive changes that occur at the cellular and molecular level in response to microgravity.

Simulating Microgravity

One of the key challenges in using microgravity as an investigative tool is creating a microgravity condition that can be applied at a cellular level, on Earth. The process of conducting space research missions is costly and time consuming, thereby limiting the advancement of microgravity research and widespread application of this approach. Currently, there are a number of microgravity devices available for purchase that are designed to achieve microgravity conditions. Microgravity simulators specific to cellular studies include strong magnetic field-induced levitation (i.e., diamagnetic simulation), as well as two-dimensional and three-dimensional clinostats, rotating wall vessels and random positioning machines (RPMs) (Huijser, 2000; Russomano et al., 2005; Herranz et al., 2012; Ikeda et al., 2017). Each of the simulation techniques has shown advantages and disadvantages however, when chosen correctly for a given experiment, the results obtained are similar to those observed in Space flight studies (Stamenkovic et al., 2010; Herranz et al., 2013; Martinez et al., 2015; Krüger et al., 2019b). For cell culture studies, the use of RPM is common as the system achieves microgravity by continually providing random changes in orientation relative to the gravity vector and thus an averaging of the impact of the gravity vector to zero occurs over time (Beysens and van Loon, 2015). This averaging is achieved by the independent, yet simultaneous, rotation of two axes – with one axis rotating in the X-plane, and the second axis rotating in the Y-plane. It is important that the cell culture flask/sample be placed at the midpoint of the x-axis, cell culture flasks placed at a distance from the center of the x-axis will be subjected to a greater rotational force resulting in cells experiencing both centrifugal force and an increased gravity load (Beysens and van Loon, 2015). Furthermore, the RPM is designed to subject the cells to 10–3 g (or as close to this value as possible) but cannot achieve complete zero gravity and hence termed microgravity (Huijser, 2000; Beysens and van Loon, 2015).

The Impact of Microgravity of Cell Cytoskeleton

Cellular response to mechanical loading has been well documented over the decades however, the response that occurs when cells are placed under conditions of mechanical unloading remains in its infancy. The most apparent cellular changes that occur following exposure to a microgravity environment are alterations to cell shape, size, volume, and adherence properties (Buken et al., 2019; Dietz et al., 2019; Thiel et al., 2019b). These microgravity induced changes to cellular morphology reflect modifications to cytoskeletal structures, namely microtubules and actin filaments (F-actin), as cells sense a reduced gravitational load and therefore mechanical unloading (Crawford-Young, 2006; Corydon et al., 2016a; Thiel et al., 2019a). Microgravity, whether in Space or simulated in the laboratory, offers a unique mechanical unloading environment to explore cellular mechanotransduction by providing an unparalleled research environment to investigate the relationship between mechanical unloading and cellular response.

Numerous studies have been conducted on a myriad of cell types highlighting morphological sensitivity to microgravity (Ingber, 1999; Vorselen et al., 2014), with the first documented morphological change reported by Rijken et al. (1991). Morphological changes as a result of microgravity conditions, either real or simulated, have been shown to have altered transcription, translation, and organization of cytoskeletal proteins (Vassy et al., 2001; Infanger et al., 2006b; Tauber et al., 2017). Fundamental work carried out by Tabony, Pochon, and Papaseit showed that while tubulin self-assembly into microtubules occurs independent of gravity, the assembly and organization of the microtubule network is gravity dependent (Papaseit et al., 2000; Tabony et al., 2002). Importantly, this gravity-dependent organization of the microtubule network has since been described in multiple cell lines during both real and simulated microgravity exposures (Vassy et al., 2001; Uva et al., 2002; Hughes-Fulford, 2003; Rosner et al., 2006; Janmaleki et al., 2016) and possibly be the result of a poorly defined microtubule organizing center (MTOC) (Lewis et al., 1998). Taken together these data highlight an important regulatory role for the microtubule network and the MTOC following exposure to a microgravity environment. However, the data surrounding the response of the actin cytoskeleton to microgravity exposure are less clear. Many studies have reported that microgravity exposure had decreased expression of actin and actin-associated proteins, namely Arp2/3 and RhoA, subsequently resulting in the disorganization of the actin cytoskeleton (Carlsson et al., 2003; Higashibata et al., 2006; Corydon et al., 2016a, b; Louis et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2018). However, other studies have showed increased F-actin and stress fiber formation that accompanied the development of lamellipodia protrusions following exposure to microgravity (Gruener et al., 1994; Nassef et al., 2019). Contrary to this, Rosner et al. (2006) reported no changes to actin structure or organization and further suggested that the actin cytoskeleton is only regulated in a hyper-gravity environment. Thus, the data surrounding cellular morphological changes in response to microgravity and the role of actin is confounding and at times contradictory.

The actin cytoskeleton, its organization and ability to generate force are critical for cellular mechanosensing and importantly any changes to these processes can initiate pathophysiological disruption. Transduction of mechanical forces by integrins requires clustering of these transmembrane receptors and the subsequent formation of focal contacts and adhesions that physically link the extracellular matrix (ECM) to the cytoskeleton (Wang et al., 1993; Ingber, 1997; Maniotis et al., 1997). Binding of integrins to matrix proteins promotes the bundling of F-actin at the cell-matrix adhesion and the subsequent maturation of both the focal adhesion and the actin stress fiber (Zaidel-Bar et al., 2003; Wolfenson et al., 2009, 2011) to generate the tension required for cell adherence, migration, and tissue homeostasis. Exposure to microgravity reduces the formation, number, and total area of focal adhesions per cell (Guignandon et al., 2003; Tan et al., 2018) consequently affecting cellular adherence, migration capacity, and viability (Plett et al., 2004; Nabavi et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2015; Ahn et al., 2019; Dietz et al., 2019), albeit with contradictory results. Mechanical unloading has been shown to significantly reduce gene expression of a number of focal adhesion proteins, including FAK, DOCK1, and PTEN, while caveolin and p130Cas expression were shown to be increased (Grenon et al., 2013; Ratushnyy and Buravkova, 2017). Thus, the activity of the downstream signaling pathways that govern the microgravity-induced cytoskeletal changes are significantly impaired and are at least in part due to the microgravity-triggered inhibition of FAK and/or RhoA signaling (Higashibata et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009; Tan et al., 2018). Furthermore, recent data suggest that changes to the cytoskeleton may also impact signaling via mechanically activated ion channels and contacts in response to both cell-generated (Nourse and Pathak, 2017; Ellefsen et al., 2019) and externally applied mechanical inputs (Bavi et al., 2019). Thus, downstream signaling of the numerous mechanotransduction pathways depend on the concerted interaction of the cytoskeleton, cell adhesion molecules, and force sensing proteins, including mechanically activated ion channels. To date, there is little information regarding the role of mechanically activated ion channels in microgravity environments.

Microgravity Impact Bone Cell Signaling Response and Cartilage ECM Synthesis

The accelerated loss of bone and muscle mass as a result of microgravity has been well documented over the decades (Burger and Klein-Nulend, 1998; Harris et al., 2000; Fitts et al., 2001). Osteocytes and osteoblasts are known mechanosensitive bone cells responsible for maintaining the balance of bone absorption and resorption – a process that is coordinated by both the actin cytoskeleton and microtubule network (Okumura et al., 2006). Bone cell morphology is significantly modified following exposure to microgravity when compared to control cells (Guignandon et al., 1995; Hughes-Fulford, 2003). To adapt to the new mechanical environment the bone cells have reduced transcription and translation of cytoskeletal and cytoskeletal-associated proteins (Xu et al., 2017; Mann et al., 2019), decreased focal adhesion formation, together resulting in the increased formation of osteoclast resorption pits (Nabavi et al., 2011). Furthermore, the actin cytoskeleton of osteoblasts subjected to 4 days of microgravity exposure completely collapsed (Hughes-Fulford, 2003), significantly impacting multiple downstream signaling pathways, most notably, the inhibition of bone morphogenic protein (BMP) signaling axis (Patel et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2017). The BMP family of proteins regulates the expression of an important mechanosensing protein, sclerostin, found exclusively in osteocytes (Poole et al., 2005; Kamiya et al., 2016), whereby mechanical unloading increases sclerostin protein expression to promote bone resorption and cause a loss of bone density (Robling et al., 2008) – a phenotype that closely mimics both osteoporosis and osteonecrosis. Thus by applying the unique mechanical unloading environment offered by both real and simulated-microgravity to bone (specifically, osteoporosis) research has led to the introduction of the FDA approved drug, Evenity, a monoclonal antibody that works as an anabolic agent to increase bone mass via the sclerostin pathway (Scheiber et al., 2019).

While a significant number of studies have identified the importance of mechanical unloading in regulating bone structure and function, the articular cartilage (AC) is also particularly susceptible to the effects of mechanical loading and unloading (Sanchez-Adams et al., 2014). The cells found in AC, chondrocytes, sense and respond to changing mechanical loads in order to maintain the balanced production of ECM molecules ensuring that the tissue maintains the ability to resist tensile and compressive forces. Both mechanical unloading and overloading of chondrocytes can disrupt the homeostatic balance in the cartilage leading to cartilage degradation and osteoarthritis thereby tipping the balance from homeostatic maintenance to pathophysiology, leading to cartilage degradation and osteoarthritis (Vanwanseele et al., 2002; Kurz et al., 2005). To study the effect of extended microgravity on AC specifically on the joint tissue, mice were exposed to 30 days of spaceflight during the Bion-M1 mission (Fitzgerald et al., 2019). Interestingly, tissue degradation was observed only in the AC of load-bearing joints, but not in minimally loaded sternal fibrocartilage highlighting a differential response to mechanical unloading and the predisposition of load bearing joints, but not structural joints, to mechanical stimuli. Additionally, decreased proteoglycan levels were found in the AC of the mice after the 30 days (Vanwanseele et al., 2002) further characterizing a mechanical unloading pathology specific to AC atrophy. Importantly, reduced proteoglycan levels have also been reported in hindlimb unloading and limb immobilization studies in various animals (Salter et al., 1980; Haapala et al., 1996; O’Connor, 1997). The reduced proteoglycan levels paired with the augmented regulation of ECM-associated genes and proteins that help protect against osteoarthritic changes, including collagen type I, II, and X, β1integrin, vimentin, and chondrocyte sulfate (Ulbrich et al., 2010; Aleshcheva et al., 2013, 2015), suggest that while the microgravity-induced osteoarthritic pathology is observed cartilage recovery of the AC is possible. Further to this, cell-based studies have shown that primary chondrocytes are to adapt to a microgravity environment within 24 h (Aleshcheva et al., 2013). There is a clear need for more research into the response of AC and specifically chondrocytes as elucidation of the molecular mechanism that underpins chondrocytes mechanoadaptation to a microgravity environment, holds great promise for novel osteoarthritic treatments.

Microgravity-Induced Cytoskeletal Regulation of Immune and Cancer Cells

The function of the immune system is strongly impacted (Frippiat et al., 2016; Smith, 2018) with several studies reporting dysregulation or immunosuppression following simulated or real microgravity conditions (Boonyaratanakornkit et al., 2005; Crucian et al., 2015; Martinez et al., 2015; Thiel et al., 2017). Peripheral monocytes collected from astronauts post short-duration Space missions (13–16 days) showed that there was no change in the numbers of circulating monocytes indicating that the change to an immunosuppressive phenotype was not due a reduced cell number (Crucian et al., 2011). However, peripheral monocytes showed a significantly decreased expression of surface markers CD26L and HLA-DR, known regulators of lymphocyte-endothelial cell adhesion and tissue migration (Crucian et al., 2011). In vitro studies performed during Space flights have revealed that lymphocytes exhibit important changes in their cytoskeletal properties, suggesting that T cell activation may be compromised at the level of the T cell receptor (TCR) interaction (Sonnenfeld et al., 1992). It has been hypothesized that immunosuppression produced in microgravity is due to impaired TCR activation resulting from cytoskeletal disruption (Bradley et al., 2019); however, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unknown.

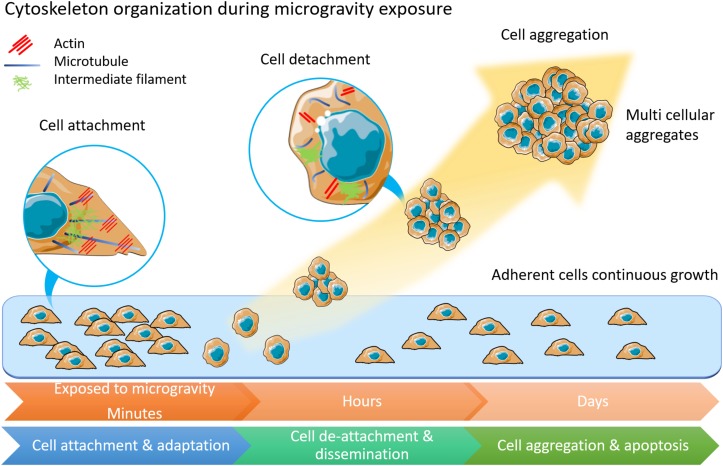

When applied to tumor cells microgravity has been found to impact tumor cell adhesion, proliferation, migration, and viability (Grimm et al., 2002; Plett et al., 2004; Infanger et al., 2006a; Shi et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2018), and to induce cell autophagy (Jeong et al., 2018). Changes in apoptotic rate were also observed in colorectal cancer cells (DLD-1) and a lymphoblast leukemic cell line (MOLT-4), accompanied by reduced transcription of the genes involved in colony formation, oncogenic progression, and metastatic potential (Vidyasekar et al., 2015). The foremost changes to tumor cell following exposure to microgravity are alterations of cell shape, size, and adhesion, indicating changes in cytoskeletal organization (Figure 1). Modulation of the cytoskeletal network have been demonstrated to occur after just minutes (Rijken et al., 1992; Sciola et al., 1999) or hours (Lewis et al., 1998; Vassy et al., 2001) in microgravity. Microtubule disorganization was observed in both the breast cancer MCF-7 cells and the thyroid cancer cell line FTC-133 when exposed to real microgravity (Kopp et al., 2018a, b). In contrast, no changes in Rac-controlled F-actin were detected in the neuroblastoma cell line, SH-Y-5Y (Rosner et al., 2006), highlighting the differing responses of distinct cell types to mechanical unloading. The expression of focal adhesion proteins, moesin and ezrin, was found to be significantly down-regulated after 24-h of microgravity exposure (Kopp et al., 2018a). There remains a gap in the understanding of the molecular mechanisms that drive changes in the cytoskeleton in response to mechanical unloading and the physiological systems that will be impacted by microgravity. Thus, there is a dual potential of microgravity studies in both elucidating the underlying importance of mechanical signaling in human physiology and in developing understanding and countermeasures for long-duration space flights.

FIGURE 1.

The morphology and physiology alterations of adherently growing cells after microgravity exposure. Cytoskeleton components of actin, microtubules and intermediate filament are displayed in inset circles. In adherent cells, microtubules form radiation arrangement near nuclear. Actin fibers anchor to cell membranes. Intermediate filament forms loose network around nuclear. Among cells under microgravity influence, the microtubules are shortened and curved. Less actin fibers but more condense intermediate filament are observed. This illustration was inspired by long-term thyroid cells culture in simulated microgravity environment (Kopp et al., 2015; Krüger et al., 2019a).

Discussion

Microgravity research conducted on the International Space Station (ISS) and in simulated microgravity has highlighted the importance of cellular mechanotransduction in human health and disease (Table 1). Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which cells respond to mechanical unloading will not only be important for preparing humans for longer-term space exploration but may also contribute to therapeutics for the treatment of diseases that depend on mechanical interactions, highlighting opportunities to manipulate and correct certain disease states. The discovery of sclerostin and the subsequent generation and use of the sclerostin monoclonal antibody to treat both osteoporotic patients has been a major outcome of the field (Martin et al., 2020). Thus, Space and microgravity biological research constitute extreme environments in which novel mechanotransduction molecules and mechanosensing mechanisms can be identified and may prove helpful in better designing immunotherapies or developing better and more targeted anti-cancer therapies. Studies that leverage these low gravity environments have the unique potential to unveil important physiological changes that occur in response to changing mechanical loads and are of considerable importance in expanding our understanding of mechanobiology.

TABLE 1.

Effects of sub-cellular functions concerning various cell types and exposure duration in microgravity environment.

| Cell type | Effects of cells | Microgravity exposure time | References |

| Osteosarcoma cells (ROS 17/2.8) | Cell morphological change to rounded shape with long cytoplasmic extensions | 4 days and 6 days | Guignandon et al., 1997 |

| Osteosarcoma cells (ROS 17/2.8) | Reduction in cell spread area and vinculin spot area, actin and focal adhesion, and stress fibers | 12 and 24 h | Guignandon et al., 2003 |

| Breast cancer (MCF-7) | Disoriented microtubule | 1.5 h | Vassy et al., 2003 |

| Thyroid cancer (ML-1) | Actin fiber reorganization | Parabola flight | Ulbrich et al., 2011 |

| Human macrophages | No effect on cytoskeletal structure | 11 days | Tauber et al., 2017 |

| Human chondrocytes | Effect on cell cytoplasm, microtubule network disruption, loss of stress fibers, actin fiber reorganization. | Parabola flight | Aleshcheva et al., 2015 |

| Osteoblasts (MC3T3-E1) | Reduction in actin cytoskeletal stress fibers and reduction of nuclei size by 30% | 4 days | Hughes-Fulford and Lewis, 1996 |

| Primary mouse osteoblasts | Thicker microtubule, smaller focal adhesion spots, reduction in actin stress fibers, and increase in cell spread area | 5 days | Nabavi et al., 2011 |

| Osteocytes | Increase in cellular organelles including Golgi complex, vacuoles, and vesicles | 14 days | Rodionova et al., 2002 |

With the privatization and commercialization of the ISS and a global push toward the exploration of space, the gateway for conducting research under simulated and Space microgravity is becoming more accessible. In particular the development of different variations of the RPM device provides a simulated microgravity environment on Earth for investigating the changes in cellular function due to mechanical unloading. Over the last several years, experiments involving the use of microgravity to study cellular mechanobiology and disease mechanisms have continued to rise, reinforcing the importance of this platform. This area of research has highlighted the importance of mechanical cues in maintaining cell and tissue homeostasis. The emergence of Space mechanobiology will continue to rise in the foreseeable future as it is evident that the benefits of such research can catapult survival of astronauts in space for extended duration as well as developing understanding and better treatments for Earth-borne diseases.

Author Contributions

PB contributed to the sections “Simulating Microgravity” and “The Impact of Microgravity of Cell Cytoskeleton.” JuC and JL contributed to the section “Microgravity Impact Bone Cell Signaling Response and Cartilage ECM Synthesis.” HW, HZ, and KP contributed to the section “Microgravity-Induced Cytoskeletal Regulation of Immune and Cancer Cells.” AR, KP, and JoC initiated, conceptualized the review, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. The author acknowledges the support of the Australian Research Council Discovery Project (ARC DP) (DP190101973), the NHMRC project grant APP1122104, and the University of Technology Sydney FEIT 2019 BlueSky grants FL160100139 (Laureate Fellowship AER) and DP190102230 (DP AER).

References

- Ahn C. B., Lee J. H., Han D. G., Kang H. W., Lee S. H., Lee J. I., et al. (2019). Simulated microgravity with floating environment promotes migration of non-small cell lung cancers. Sci. Rep. 9:14553. 10.1038/s41598-019-50736-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleshcheva G., Sahana J., Ma X., Hauslage J., Hemmersbach R., Egli M., et al. (2013). Changes in morphology, gene expression and protein content in chondrocytes cultured on a random positioning machine. PLoS One 8:e79057. 10.1371/journal.pone.0079057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleshcheva G., Wehland M., Sahana J., Bauer J., Corydon T. J., Hemmersbach R., et al. (2015). Moderate alterations of the cytoskeleton in human chondrocytes after short-term microgravity produced by parabolic flight maneuvers could be prevented by up-regulation of BMP-2 and SOX-9. FASEB J. 29 2303–2314. 10.1096/fj.14-268151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavi N., Richardson J., Heu C., Martinac B., Poole K. (2019). PIEZO1-mediated currents are modulated by substrate mechanics. ACS Nano 13 13545–13559. 10.1021/acsnano.9b07499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beysens D. A., van Loon J. J. W. A. (2015). Generation and Applications of Extra-Terrestrial Environments on Earth. Denmark: River Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Boonyaratanakornkit J. B., Cogoli A., Li C. F., Schopper T., Pippia P., Galleri G., et al. (2005). Key gravity-sensitive signaling pathways drive T cell activation. FASEB J. 19 2020–2022. 10.1096/fj.05-3778fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley J. H., Barwick S., Horn G. Q., Ullrich E., Best B., Arnold J. P., et al. (2019). Simulated microgravity-mediated reversion of murine lymphoma immune evasion. Sci. Rep. 9:14623. 10.1038/s41598-019-51106-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buken C., Sahana J., Corydon T. J., Melnik D., Bauer J., Wehland M., et al. (2019). Morphological and molecular changes in juvenile normal human fibroblasts exposed to simulated microgravity. Sci. Rep. 9:11882. 10.1038/s41598-019-48378-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger E. H., Klein-Nulend J. (1998). Microgravity and bone cell mechanosensitivity. Bone 22(5 Suppl.), 127S–130S. 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00010-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson S. I., Bertilaccio M. T., Ballabio E., Maier J. A. (2003). Endothelial stress by gravitational unloading: effects on cell growth and cytoskeletal organization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1642 173–179. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2003.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corydon T. J., Kopp S., Wehland M., Braun M., Schutte A., Mayer T., et al. (2016a). Alterations of the cytoskeleton in human cells in space proved by life-cell imaging. Sci. Rep. 6:20043. 10.1038/srep20043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corydon T. J., Mann V., Slumstrup L., Kopp S., Sahana J., Askou A. L., et al. (2016b). Reduced expression of cytoskeletal and extracellular matrix genes in human adult retinal pigment epithelium cells exposed to simulated microgravity. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 40 1–17. 10.1159/000452520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford-Young S. J. (2006). Effects of microgravity on cell cytoskeleton and embryogenesis. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 50 183–191. 10.1387/ijdb.052077sc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crucian B., Simpson R. J., Mehta S., Stowe R., Chouker A., Hwang S. A., et al. (2014). Terrestrial stress analogs for spaceflight associated immune system dysregulation. Brain Behav. Immun. 39 23–32. 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crucian B., Stowe R., Quiriarte H., Pierson D., Sams C. (2011). Monocyte phenotype and cytokine production profiles are dysregulated by short-duration spaceflight. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 82 857–862. 10.3357/asem.3047.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crucian B., Stowe R. P., Mehta S., Quiriarte H., Pierson D., Sams C. (2015). Alterations in adaptive immunity persist during long-duration spaceflight. NPJ Microgravity 1:15013. 10.1038/npjmgrav.2015.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz C., Infanger M., Romswinkel A., Strube F., Kraus A. (2019). Apoptosis induction and alteration of cell adherence in human lung cancer cells under simulated microgravity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:E3601. 10.3390/ijms20143601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellefsen K. L., Holt J. R., Chang A. C., Nourse J. L., Arulmoli J., Mekhdjian A. H., et al. (2019). Myosin-II mediated traction forces evoke localized Piezo1-dependent Ca(2+) flickers. Commun. Biol. 2:298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitts R. H., Riley D. R., Widrick J. J. (2001). Functional and structural adaptations of skeletal muscle to microgravity. J. Exp. Biol. 204(Pt 18), 3201–3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald J., Endicott J., Hansen U., Janowitz C. (2019). Articular cartilage and sternal fibrocartilage respond differently to extended microgravity. NPJ Microgravity 5:3. 10.1038/s41526-019-0063-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frippiat J. P., Crucian B. E., de Quervain D. J., Grimm D., Montano N., Praun S., et al. (2016). Towards human exploration of space: the THESEUS review series on immunology research priorities. NPJ Microgravity 2:16040. 10.1038/npjmgrav.2016.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenon S. M., Jeanne M., Aguado-Zuniga J., Conte M. S., Hughes-Fulford M. (2013). Effects of gravitational mechanical unloading in endothelial cells: association between caveolins, inflammation and adhesion molecules. Sci. Rep. 3:1494. 10.1038/srep01494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D., Bauer J., Kossmehl P., Shakibaei M., Schoberger J., Pickenhahn H., et al. (2002). Simulated microgravity alters differentiation and increases apoptosis in human follicular thyroid carcinoma cells. FASEB J. 16 604–606. 10.1096/fj.01-0673fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruener R., Roberts R., Fau-Reitstetter R., Reitstetter R. (1994). Reduced receptor aggregation and altered cytoskeleton in cultured myocytes after space-flight. Biol. Sci. Space 8 79–93. 10.2187/bss.8.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guignandon A., Akhouayri O., Usson Y., Rattner A., Laroche N., Lafage-Proust M. H., et al. (2003). Focal contact clustering in osteoblastic cells under mechanical stresses: microgravity and cyclic deformation. Cell Commun. Adhes. 10 69–83. 10.1080/15419060390260987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guignandon A., Genty C., Vico L., Lafage-Proust M. H., Palle S., Alexandre C. (1997). Demonstration of feasibility of automated osteoblastic line culture in space flight. Bone 20 109–116. 10.1016/s8756-3282(96)00337-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guignandon A., Vico L., Alexandre C., Lafage-Proust M. H. (1995). Shape changes of osteoblastic cells under gravitational variations during parabolic flight–relationship with PGE2 synthesis. Cell Struct. Funct. 20 369–375. 10.1247/csf.20.369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haapala J., Lammi M. J., Inkinen R., Parkkinen J. J., Agren U. M., Arokoski J., et al. (1996). Coordinated regulation of hyaluronan and aggrecan content in the articular cartilage of immobilized and exercised dogs. J. Rheumatol. 23 1586–1593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris S. A., Zhang M., Kidder L. S., Evans G. L., Spelsberg T. C., Turner R. T. (2000). Effects of orbital spaceflight on human osteoblastic cell physiology and gene expression. Bone 26 325–331. 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00234-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz R., Anken R., Boonstra J., Braun M., Christianen P. C., de Geest M., et al. (2013). Ground-based facilities for simulation of microgravity: organism-specific recommendations for their use, and recommended terminology. Astrobiology 13 1–17. 10.1089/ast.2012.0876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz R., Larkin O. J., Dijkstra C. E., Hill R. J., Anthony P., Davey M. R., et al. (2012). Microgravity simulation by diamagnetic levitation: effects of a strong gradient magnetic field on the transcriptional profile of Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Genomics 13:52. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashibata A., Imamizo-Sato M., Seki M., Yamazaki T., Ishioka N. (2006). Influence of simulated microgravity on the activation of the small GTPase Rho involved in cytoskeletal formation–molecular cloning and sequencing of bovine leukemia-associated guanine nucleotide exchange factor. BMC Biochem. 7:19. 10.1186/1471-2091-7-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horneck G., Facius R., Reichert M., Rettberg P., Seboldt W., Manzey D., et al. (2003). HUMEX, a study on the survivability and adaptation of humans to long-duration exploratory missions, part I: lunar missions. Adv. Space Res. 31 2389–2401. 10.1016/s0273-1177(03)00568-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes-Fulford M. (2003). Function of the cytoskeleton in gravisensing during spaceflight. Adv. Space Res. 32 1585–1593. 10.1016/s0273-1177(03)90399-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes-Fulford M., Lewis M. L. (1996). Effects of microgravity on osteoblast growth activation. Exp. Cell Res. 224 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijser R. (2000). Desktop RPM: New Small Size Microgravity Simulator for the Bioscience Laboratory. Amsterdam: Fokker Space. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H., Souda H., Puspitasari A., Held K. D., Hidema J., Nikawa T., et al. (2017). Development and performance evaluation of a three-dimensional clinostat synchronized heavy-ion irradiation system. Life Sci. Space Res. 12 51–60. 10.1016/j.lssr.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infanger M., Kossmehl P., Shakibaei M., Baatout S., Witzing A., Grosse J., et al. (2006a). Induction of three-dimensional assembly and increase in apoptosis of human endothelial cells by simulated microgravity: impact of vascular endothelial growth factor. Apoptosis 11 749–764. 10.1007/s10495-006-5697-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infanger M., Kossmehl P., Shakibaei M., Bauer J., Kossmehl-Zorn S., Cogoli A., et al. (2006b). Simulated weightlessness changes the cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix proteins in papillary thyroid carcinoma cells. Cell Tissue Res. 324 267–277. 10.1007/s00441-005-0142-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber D. (1999). How cells (might) sense microgravity. FASEB J. 13(Suppl.), S3–S15. 10.1096/fasebj.13.9001.s3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber D. E. (1997). Tensegrity: the architectural basis of cellular mechanotransduction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 59 575–599. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janmaleki M., Pachenari M., Seyedpour S. M., Shahghadami R., Sanati-Nezhad A. (2016). Impact of simulated microgravity on cytoskeleton and viscoelastic properties of endothelial cell. Sci. Rep. 6:32418. 10.1038/srep32418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong A. J., Kim Y. J., Lim M. H., Lee H., Noh K., Kim B.-H., et al. (2018). Microgravity induces autophagy via mitochondrial dysfunction in human Hodgkin’s lymphoma cells. Sci. Rep. 8:14646. 10.1038/s41598-018-32965-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya N., Shuxian L., Yamaguchi R., Phipps M., Aruwajoye O., Adapala N. S., et al. (2016). Targeted disruption of BMP signaling through type IA receptor (BMPR1A) in osteocyte suppresses SOST and RANKL, leading to dramatic increase in bone mass, bone mineral density and mechanical strength. Bone 91 53–63. 10.1016/j.bone.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp S., Krüger M., Feldmann S., Oltmann H., Schütte A., Schmitz B., et al. (2018a). Thyroid cancer cells in space during the TEXUS-53 sounding rocket mission – the THYROID project. Sci. Rep. 8:10355. 10.1038/s41598-018-28695-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp S., Sahana J., Islam T., Petersen A. G., Bauer J., Corydon T. J., et al. (2018b). The role of NFκB in spheroid formation of human breast cancer cells cultured on the Random Positioning Machine. Sci. Rep. 8:921. 10.1038/s41598-017-18556-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp S., Warnke E., Wehland M., Aleshcheva G., Magnusson N. E., Hemmersbach R., et al. (2015). Mechanisms of three-dimensional growth of thyroid cells during long-term simulated microgravity. Sci. Rep. 5:16691. 10.1038/srep16691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger M., Melnik D., Kopp S., Buken C., Sahana J., Bauer J., et al. (2019a). Fighting thyroid cancer with microgravity research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:2553. 10.3390/ijms20102553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger M., Pietsch J., Bauer J., Kopp S., Carvalho D. T. O., Baatout S., et al. (2019b). Growth of endothelial cells in space and in simulated microgravity - a comparison on the secretory level. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 52 1039–1060. 10.33594/000000071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz B., Lemke A. K., Fay J., Pufe T., Grodzinsky A. J., Schunke M. (2005). Pathomechanisms of cartilage destruction by mechanical injury. Ann. Anat. 187 473–485. 10.1016/j.aanat.2005.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. L., Reynolds J. L., Cubano L. A., Hatton J. P., Lawless B. D., Piepmeier E. H. (1998). Spaceflight alters microtubules and increases apoptosis in human lymphocytes (Jurkat). FASEB J. 12 1007–1018. 10.1096/fasebj.12.11.1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Zhang S., Chen J., Du T., Wang Y., Wang Z. (2009). Modeled microgravity causes changes in the cytoskeleton and focal adhesions, and decreases in migration in malignant human MCF-7 cells. Protoplasma 238 23–33. 10.1007/s00709-009-0068-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis F., Bouleftour W., Rattner A., Linossier M. T., Vico L., Guignandon A. (2017). RhoGTPase stimulation is associated with strontium chloride treatment to counter simulated microgravity-induced changes in multipotent cell commitment. NPJ Microgravity 3:7. 10.1038/s41526-016-0004-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniotis A. J., Chen C. S., Ingber D. E. (1997). Demonstration of mechanical connections between integrins, cytoskeletal filaments, and nucleoplasm that stabilize nuclear structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 849–854. 10.1073/pnas.94.3.849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann V., Grimm D., Corydon T. J., Kruger M., Wehland M., Riwaldt S., et al. (2019). Changes in human foetal osteoblasts exposed to the random positioning machine and bone construct tissue engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:1357. 10.3390/ijms20061357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M., Sansalone V., Cooper D. M. L., Forwood M. R., Pivonka P. (2020). Assessment of romosozumab efficacy in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: results from a mechanistic PK-PD mechanostat model of bone remodeling. Bone 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115223 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez E. M., Yoshida M. C., Candelario T. L., Hughes-Fulford M. (2015). Spaceflight and simulated microgravity cause a significant reduction of key gene expression in early T-cell activation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 308 R480–R488. 10.1152/ajpregu.00449.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabavi N., Khandani A., Camirand A., Harrison R. E. (2011). Effects of microgravity on osteoclast bone resorption and osteoblast cytoskeletal organization and adhesion. Bone 49 965–974. 10.1016/j.bone.2011.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassef M. Z., Kopp S., Wehland M., Melnik D., Sahana J., Kruger M., et al. (2019). Real microgravity influences the cytoskeleton and focal adhesions in human breast cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:3156. 10.3390/ijms20133156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourse J. L., Pathak M. M. (2017). How cells channel their stress: interplay between Piezo1 and the cytoskeleton. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 71 3–12. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor K. M. (1997). Unweighting accelerates tidemark advancement in articular cartilage at the knee joint of rats. J. Bone Miner. Res. 12 580–589. 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.4.580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura S., Mizoguchi T., Sato N., Yamaki M., Kobayashi Y., Yamauchi H., et al. (2006). Coordination of microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton is important in osteoclast function, but calcitonin disrupts sealing zones without affecting microtubule networks. Bone 39 684–693. 10.1016/j.bone.2006.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajevic P. D., Spatz J. M., Garr J., Adamson C., Misener L. (2013). Osteocyte biology and space flight. Curr. Biotechnol. 2 179–183. 10.2174/22115501113029990017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaseit C., Pochon N., Tabony J. (2000). Microtubule self-organization is gravity-dependent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 8364–8368. 10.1073/pnas.140029597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M. J., Liu W., Sykes M. C., Ward N. E., Risin S. A., Risin D., et al. (2007). Identification of mechanosensitive genes in osteoblasts by comparative microarray studies using the rotating wall vessel and the random positioning machine. J. Cell Biochem. 101 587–599. 10.1002/jcb.21218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlakou P., Dounousi E., Roumeliotis S., Eleftheriadis T., Liakopoulos V. (2018). Oxidative stress and the kidney in the space environment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:3176. 10.3390/ijms19103176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plett P. A., Abonour R., Frankovitz S. M., Orschell C. M. (2004). Impact of modeled microgravity on migration, differentiation, and cell cycle control of primitive human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Exp. Hematol. 32 773–781. 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K. E., van Bezooijen R. L., Loveridge N., Hamersma H., Papapoulos S. E., Lowik C. W., et al. (2005). Sclerostin is a delayed secreted product of osteocytes that inhibits bone formation. FASEB J. 19 1842–1844. 10.1096/fj.05-4221fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratushnyy A. Y., Buravkova L. B. (2017). Expression of focal adhesion genes in mesenchymal stem cells under simulated microgravity. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 477 354–356. 10.1134/s1607672917060035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijken P. J., de Groot R. P., Briegleb W., Kruijer W., Verkleij A. J., Boonstra J., et al. (1991). Epidermal growth factor-induced cell rounding is sensitive to simulated microgravity. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 62 32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijken P. J., de Groot R. P., Kruijer W., de Laat S. W., Verkleij A. J., Boonstra J. (1992). Identification of specific gravity sensitive signal transduction pathways in human A431 carcinoma cells. Adv. Space Res. 12 145–152. 10.1016/0273-1177(92)90277-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robling A. G., Niziolek P. J., Baldridge L. A., Condon K. W., Allen M. R., Alam I., et al. (2008). Mechanical stimulation of bone in vivo reduces osteocyte expression of Sost/sclerostin. J. Biol. Chem. 283 5866–5875. 10.1074/jbc.M705092200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodionova N. V., Oganov V. S., Zolotova N. V. (2002). Ultrastructural changes in osteocytes in microgravity conditions. Adv. Space Res. 30 765–770. 10.1016/s0273-1177(02)00393-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner H., Wassermann T., Moller W., Hanke W. (2006). Effects of altered gravity on the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton of human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Protoplasma 229 225–234. 10.1007/s00709-006-0202-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russomano T., Cardoso R., Falcao F., Dalmarco G., Santos C. V. D., Santos L. F. D., et al. (2005). Development and validation of a 3D clinostat for the study of cells during microgravity simulation. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 1 564–566. 10.1109/iembs.2005.1616474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter R. B., Simmonds D. F., Malcolm B. W., Rumble E. J., MacMichael D., Clements N. D. (1980). The biological effect of continuous passive motion on the healing of full-thickness defects in articular cartilage. An experimental investigation in the rabbit. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 62 1232–1251. 10.2106/00004623-198062080-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Adams J., Leddy H. A., McNulty A. L., O’Conor C. J., Guilak F. (2014). The mechanobiology of articular cartilage: bearing the burden of osteoarthritis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 16:451. 10.1007/s11926-014-0451-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiber A. L., Barton D. K., Khoury B. M., Marini J. C., Swiderski D. L., Caird M. S., et al. (2019). Sclerostin antibody-induced changes in bone mass are site specific in developing Crania. J. Bone Miner. Res. 34 2301–2310. 10.1002/jbmr.3858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciola L., Cogoli-Greuter M., Cogoli A., Spano A., Pippia P. (1999). Influence of microgravity on mitogen binding and cytoskeleton in Jurkat cells. Adv. Space Res. 24 801–805. 10.1016/s0273-1177(99)00078-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z. X., Rao W., Wang H., Wang N. D., Si J. W., Zhao J., et al. (2015). Modeled microgravity suppressed invasion and migration of human glioblastoma U87 cells through downregulating store-operated calcium entry. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 457 378–384. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.12.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. K. (2018). IL-6 and the dysregulation of immune, bone, muscle, and metabolic homeostasis during spaceflight. NPJ Microgravity 4:24. 10.1038/s41526-018-0057-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenfeld G., Mandel A. D., Konstantinova I. V., Berry W. D., Taylor G. R., Lesnyak A. T., et al. (1992). Spaceflight alters immune cell function and distribution. J. Appl. Physiol. 73(2 Suppl.), 191S–195S. 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.2.S191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamenkovic V., Keller G., Nesic D., Cogoli A., Grogan S. P. (2010). Neocartilage formation in 1 g, simulated, and microgravity environments: implications for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part A 16 1729–1736. 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabony J., Glade N., Papaseit C., Demongeot J. (2002). Microtubule self-organisation and its gravity dependence. Adv. Space Biol. Med. 8 19–58. 10.1016/s1569-2574(02)08014-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X., Xu A., Zhao T., Zhao Q., Zhang J., Fan C., et al. (2018). Simulated microgravity inhibits cell focal adhesions leading to reduced melanoma cell proliferation and metastasis via FAK/RhoA-regulated mTORC1 and AMPK pathways. Sci. Rep. 8:3769. 10.1038/s41598-018-20459-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauber S., Lauber B. A., Paulsen K., Layer L. E., Lehmann M., Hauschild S., et al. (2017). Cytoskeletal stability and metabolic alterations in primary human macrophages in long-term microgravity. PLoS One 12:e0175599. 10.1371/journal.pone.0175599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel C. S., Hauschild S., Huge A., Tauber S., Lauber B. A., Polzer J., et al. (2017). Dynamic gene expression response to altered gravity in human T cells. Sci. Rep. 7:5204. 10.1038/s41598-017-05580-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel C. S., Tauber S., Lauber B., Polzer J., Seebacher C., Uhl R., et al. (2019a). Rapid morphological and cytoskeletal response to microgravity in human primary macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:2402. 10.3390/ijms20102402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel C. S., Tauber S., Seebacher C., Schropp M., Uhl R., Lauber B., et al. (2019b). Real-time 3D high-resolution microscopy of human cells on the international space station. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:2033. 10.3390/ijms20082033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulbrich C., Westphal K., Pietsch J., Winkler H. D., Leder A., Bauer J., et al. (2010). Characterization of human chondrocytes exposed to simulated microgravity. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 25 551–560. 10.1159/000303059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulbrich C., Pietsch J., Grosse J., Wehland M., Schulz H., Saar K., et al. (2011). Differential gene regulation under altered gravity conditions in follicular thyroid cancer cells: relationship between the extracellular matrix and the cytoskeleton. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 28 185–198. 10.1159/000331730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uva B. M., Masini M. A., Sturla M., Prato P., Passalacqua M., Giuliani M., et al. (2002). Clinorotation-induced weightlessness influences the cytoskeleton of glial cells in culture. Brain Res. 934 132–139. 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02415-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanwanseele B., Eckstein F., Knecht H., Stussi E., Spaepen A. (2002). Knee cartilage of spinal cord-injured patients displays progressive thinning in the absence of normal joint loading and movement. Arthritis Rheum. 46 2073–2078. 10.1002/art.10462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassy J., Portet S., Beil M., Millot G., Fauvel-Lafeve F., Karniguian A., et al. (2001). The effect of weightlessness on cytoskeleton architecture and proliferation of human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. FASEB J. 15 1104–1106. 10.1096/fj.00-0527fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassy J., Portet S., Beil M., Millot G., Fauvel-Laféve F., Gasset G., et al. (2003). Weightlessness acts on human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Adv. Space Res. 32 1595–1603. 10.1016/S0273-1177(03)90400-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidyasekar P., Shyamsunder P., Arun R., Santhakumar R., Kapadia N. K., Kumar R., et al. (2015). Genome wide expression profiling of cancer cell lines cultured in microgravity reveals significant dysregulation of cell cycle and MicroRNA gene networks. PLoS One 10:e0135958. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorselen D., Roos W. H., MacKintosh F. C., Wuite G. J., van Loon J. J. (2014). The role of the cytoskeleton in sensing changes in gravity by nonspecialized cells. FASEB J. 28 536–547. 10.1096/fj.13-236356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N., Butler J. P., Ingber D. E. (1993). Mechanotransduction across the cell surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science 260 1124–1127. 10.1126/science.7684161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White O., Clement G., Fortrat J. O., Pavy-LeTraon A., Thonnard J. L., Blanc S., et al. (2016). Towards human exploration of space: the THESEUS review series on neurophysiology research priorities. NPJ Microgravity 2:16023. 10.1038/npjmgrav.2016.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R. J., Averner M. (2001). Humans in space. Nature 409 1115–1118. 10.1038/35059243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfenson H., Bershadsky A., Henis Y. I., Geiger B. (2011). Actomyosin-generated tension controls the molecular kinetics of focal adhesions. J. Cell Sci. 124(Pt 9), 1425–1432. 10.1242/jcs.077388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfenson H., Lubelski A., Regev T., Klafter J., Henis Y. I., Geiger B. (2009). A role for the juxtamembrane cytoplasm in the molecular dynamics of focal adhesions. PLoS One 4:e4304. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Wu F., Zhang H., Yang C., Li K., Wang H., et al. (2017). Actin cytoskeleton mediates BMP2-Smad signaling via calponin 1 in preosteoblast under simulated microgravity. Biochimie 138 184–193. 10.1016/j.biochi.2017.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidel-Bar R., Ballestrem C., Kam Z., Geiger B. (2003). Early molecular events in the assembly of matrix adhesions at the leading edge of migrating cells. J. Cell Sci. 116(Pt 22), 4605–4613. 10.1242/jcs.00792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]