Abstract

Introduction:

Emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global threat and significantly affects the treatment options for common infectious diseases. Inappropriate use of antibiotics, particularly third-generation cephalosporins, has contributed to the development of AMR. This study aims to determine the prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) production in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species isolated from various clinical samples.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study was conducted at International Friendship Children’s Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal, from August 2017 to January 2018. A total of 1443 samples that included urine, pus, wound swab, endotracheal tip, catheter tip, and blood were collected from pediatric patients below 15 years and processed by standard microbiological methods. Following sufficient incubation, isolates were identified by colony morphology, gram staining, and necessary biochemical tests. Identified bacterial isolates were then tested for antibiotic susceptibility test by modified Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method and were subjected to ESBL screening by using 30 µg cefotaxime and ceftazidime. The ESBL production was confirmed by combination disk method.

Results:

From a total of 103 nonduplicated clinical isolates, E. coli (n = 79), Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 18), and Klebsiella oxytoca (n = 6) were isolated from different clinical specimens. Of which, 64 (62.1%) exhibited multidrug resistance, and 29 (28.2%) were ESBL producers. All ESBL-producing isolates were resistant toward ampicillin, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, and ceftazidime. Most ESBL producers were susceptible toward imipenem (89.7%; 26/29), nitrofurantoin (82.8%; 24/29), piperacillin/tazobactam (79.3%; 23/29), and amikacin (72.4%; 21/29).

Conclusions:

A high prevalence of multidrug-resistant ESBL organisms was found in this study among pediatric patients. Treatment based on their routine identification and susceptibility to specific antibiotics is critical to halt the spread of AMR and ESBL.

Keywords: Antibiotic resistance, ESBL, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella oxytoca, Klebsiella pneumoniae, MDR

Introduction

Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species are the most common causative pathogens for most of the infections, especially in countries with poor health care system.1 E. coli is a normal flora of human and animal gut but can also be found in water, soil, and vegetation.2 Klebsiella species are considered as major opportunistic pathogens that can cause infections mostly in children. Klebsiella pneumoniae is an important cause of human infections among all Klebsiella species, followed by Klebsiella oxytoca, Klebsiella ozaenae, and Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis. Several common bacterial infections such as gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection (UTI), septicemia, and neonatal meningitis are mainly caused by E. coli and Klebsiella spp in children.3,4

Commonly used antimicrobial agents against these pathogens are tetracycline, β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and cotrimoxazole. However, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) among Enterobacteriaceae has increased dramatically in recent years, limiting the therapeutic options. Isolates that are not susceptible to at least 3 or more groups of antimicrobials are known as multidrug resistant (MDR) organisms.5

Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) are class A β-lactamases, a rapidly evolving group of β-lactamases with the ability to hydrolyze and cause resistance to the oxy-imino cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefuroxime, and cefepime) and monobactams (aztreonam).6 ESBL-producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae are the predominant cause of childhood infections and present significant challenges7 such as development of adverse outcomes,8 treatment failure due to multidrug resistance, and high morbidity and mortality.9 Empirical and symptomatic (without a diagnosis) use of antibiotics in resource poor settings is responsible for higher incidence of antibiotic resistance among bacteria.10

Several studies in the past have investigated the prevalence of ESBL organisms among inpatients, mostly focused in adult patients.11-13 Studies have shown the varying prevalence of ESBL organisms, for instance, the prevalence was 27.7% in Pokhara,11 18% in Kathmandu,14 43% in pediatric hospital in Kathmandu.15 Another study reported 35.9% ESBL in E coil isolates among outpatients at tertiary care hospital in Kathmandu.12 However, similar study from Lalitpur district reported 6.8% ESBL-producing isolates.13 Studies have shown the wide range in the prevalence of ESBLs (10%-43%) in different hospitals/settings from various samples.

Although it is deemed to be essential to have a routine diagnosis and monitoring of ESBL-producing clinical isolates in clinical laboratories, ESBL screening as a routine test has not yet been practiced in Nepal.16 In addition, very few studies have reported on ESBL-producing clinical isolates from pediatric patients in Nepal. Only 1 study in the past has reported ESBLs (prevalence: 38.9%) from urine samples in pediatric patients from a tertiary teaching hospital in Kathmandu.17 Expanding and building on the previous research, this study focused to isolate both E. coli and Klebsiella spp from wider and larger number of clinical specimens from pediatric patients. The main objectives of this study were to explore the prevalence of ESBL-producing organisms, including the resistance types among pediatric patients attending a tertiary care pediatric hospital at Kathmandu.

Methods

Study design, area, and sample population

This was a cross-sectional study conducted at International Friendship Children’s Hospital, Maharajgunj, Kathmandu, Nepal, during August 2017 to January 2018. The study population comprised children below 15 years attending the hospital for treatment.

The specimens were collected adhering to a standard protocol from pediatric patients below 15 years of age. Children who attended the hospital for treatment and provided assent (from parents) or consent for the study were included in the study. Children who had chronic diseases such as leukemia, malnutrition, and neuropsychiatric disorders based on the diagnosis made by clinicians, including if they were initiated with the antibiotic treatment after the admission, were excluded.

A total of 1443 different samples that included urine (n = 1050), pus (n = 50), wound swabs (n = 40), endotracheal tip (n = 83), catheter tip (n = 40), and blood (n = 140) were collected and processed by standard microbiological methods.18

Sample collection and transport

Special measures were taken to collect the urine samples from children who were not able to use toilet on their own. An adhesive, sealed, sterile collection bag was placed underneath the genitalia to collect urine sample. Toilet-trained children were requested to collect mid-stream urine assisted by their parents in a sterile, dry, wide-necked, and leak-proof container. In either condition, genitalia were cleansed with alcohol swab to reduce contamination.

In the case of infected wounds, in addition to wound swab, pus was aspirated in syringe by trained medical personnel. In case pus was not discharging, cotton swab was gently rolled over the surface of the wound approximately 5 times, focusing on areas where there was evidence of pus or inflamed tissue. Two swabs were taken from each patient, one for culture and another for direct gram staining.

About 2 mL of blood from children was withdrawn and dispensed into sterile screw capped culture bottles containing BHI (brain heart infusion) broth. Specimens were collected from other sources such as endotracheal and catheter tips by trained medical personnel. The collected samples were labeled properly and were immediately delivered to a laboratory for further processing. When immediate delivery was not possible, the specimens were refrigerated at 4°C to 6°C.19

Laboratory examinations of samples

Culture

For processing of each sample, microbiological protocols were followed according to standard microbiological guidelines.18,20

Urine sample: Using a sterile calibrated loop, urine sample was inoculated on MacConkey agar (MA) and blood agar (BA), and then incubated aerobically at 37°C for 24 hours. Colony count was made, and positive result was considered for plates showing more than or equal to 105 colony forming units (CFU)/mL of urine based on Kass, Marple, and Sanford criteria.20

Blood sample: Blood sample was incubated on BHI broth for 7 days at 37°C. Bottles showing turbidity during the period were subcultured aerobically in MA and BA at 37°C for 24 to 48 hours.

Pus, wound swab specimens were inoculated into MA and BA plate sand incubated at 37°C overnight.

Other specimens: Endotracheal and catheter tips were first incubated on BHI broth at 37°C for 24 hours and subcultured on MA and BA plates and incubated at 37°C overnight.

Identification of E. coli and Klebsiella spp

Presumptive identification of E coli and Klebsiella spp was done on the basis of colony color and Gram staining morphology. Then, obtained pure cultures of isolates were assessed for various biochemical tests (indole, methyl red, Voges-Proskauer, citrate, triple sugar iron agar, oxidative/fermentative, urease test for confirmation).18,20

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

All identified isolates of E coli and Klebsiella spp were treated for susceptibility testing against ampicillin (10 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), amikacin (30 μg), aztreonam (30 μg), cefoxitin (30 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg) ciprofloxacin (5 μg), imipenem (10 μg), piperacillin/tazobactam (100/10 μg), nitrofurantoin (300 µg), and cefepime (30 μg) (HiMedia India Pvt. Ltd, Bengaluru, India) following Kirby-Bauer method on Mueller-Hinton Agar (HiMedia India Pvt. Ltd). Results were interpreted based on the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) 2016 guidelines.21 Those isolates which were not susceptible (either resistant or intermediate) to 3 or more antibiotics classes were considered as MDR.5

Screening and confirmation of ESBL producers

Bacterial isolates exhibiting reduced susceptibility to ceftazidime (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg), and aztreonam (30 μg) were considered as potential ESBL producers. The ESBL production was further phenotypically confirmed by combination disk method as described by CLSI 2014. The disk used was cefotaxime and ceftazidime alone and cefotaxime and ceftazidime in combination with clavulanic acid. A ⩾5 mm increase in growth inhibition zone for any antimicrobial associated with clavulanic acid in comparison with the inhibition zone of antibiotic tested alone confirmed ESBL production.21

Quality control

Each batch of media and reagents was subjected to sterility and performance testing. During antibiotic susceptibility test, quality control was done using the control strains of E coli ATCC 25922.

Data management and statistical analysis

Data were entered and analyzed by using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive and inferential statistics were analyzed.

Results

Prevalence of bacterial isolates

A total of 1443 different clinical specimens were processed during the study, of which 299 (20.7%) samples showed bacterial growth. Of the 299 isolates, 79 (26.4%), 18 (6.0%), and 6 (2%) were identified as E. coli, K. pneumonia, and K. oxytoca, respectively. E. coli was predominant bacteria isolated from urine samples (86.0%; 68/79), followed by pus/wound pus samples (8.8%; 7/79). K. pneumoniae (77.8%; 14/18) and K. oxytoca (83.3%; 5/6) were mostly isolated from urine samples (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of bacterial isolates in various clinical specimens of children.

| Samples | Total (%) | Bacterial isolates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli (%) | Klebsiella pneumoniae (%) | Klebsiella oxytoca (%) | ||

| Urine | 87 (84.5) | 68 (86.0) | 14 (77.8) | 5 (83.3) |

| Pus/wound pus | 11 (10.7) | 7 (8.8) | 3 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) |

| Endotracheal tip | 2 (1.9) | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Catheter tip | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (5.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Blood | 1 (1) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 103 (100.0) | 79 (76.7) | 18 (17.5) | 6 (5.8) |

Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of bacterial isolates

Among 103 bacterial isolates, 90.3% (n = 93) were found to be susceptible to imipenem, followed by piperacillin/tazobactam (88.3%; n = 91), nitrofurantoin (85.5%; n = 88), and amikacin (82.5%; n = 85). Most E. coli isolates (92.4%; 73/79) were found to be susceptible to imipenem, followed by nitrofurantoin (91.2%; 72/79). Similarly, 88.9% (16/18) of K. pneumoniae were found to be susceptible to amikacin. K. oxytoca were found to be 100% (6/6) susceptible to gentamicin, piperacillin/tazobactam, and imipenem (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of bacterial isolates (Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp).

| Antibiotics | Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of E. coli and Klebsiella spp | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Klebsiella oxytoca | ||||

| Sensitive (%) | Resistant (%) | Sensitive (%) | Resistant (%) | Sensitive (%) | Resistant (%) | |

| Gentamicin | 66 (83.5) | 13 (16.5) | 12 (66.7) | 6 (33.3) | 6 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Amikacin | 64 (81.0) | 15 (19.0) | 16 (88.9) | 2 (11.1) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 40 (50.6) | 39 (49.4) | 6 (33.3) | 12 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| Ampicillin | 22 (27.8) | 57 (72.2) | 1 (5.6) | 17 (94.4) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) |

| Piperacillin\tazobactam | 70 (88.61) | 9 (11.9) | 15 (83.3) | 3 (16.7) | 6 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Imipenem | 73 (92.4) | 6 (7.6) | 14 (77.8) | 4 (22.2) | 6 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Aztreonam | 60 (76.0) | 19 (24.0) | 11 (61.1) | 7 (38.9) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| Cefotaxime | 35 (44.3) | 44 (55.7) | 3 (16.7) | 15 (83.3) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Ceftriaxone | 37 (46.8) | 42 (53.2) | 7 (38.9) | 11 (61.1) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Ceftazidime | 37 (46.8) | 42 (53.2) | 7 (38.9) | 11 (61.1) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Cefepime | 42 (53.2) | 37 (46.8) | 11 (61.1) | 7 (38.9) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Cefoxitin | 53 (67.1) | 26 (32.9) | 7 (38.9) | 11 (61.1) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| Nitrofurantoin | 72 (91.2) | 7 (8.8) | 12 (66.7.8) | 6 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) |

MDR profile in bacterial isolate

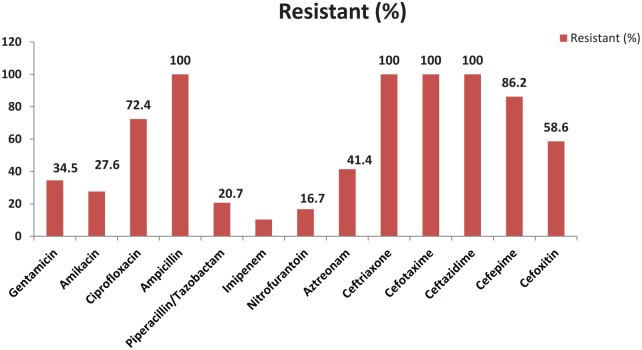

Among the total of 103 bacterial isolates, 62.1% (64/103) were found to be MDR; the highest MDR strains were detected in K. pneumoniae (88.9%; 16/18), followed by E. coli (57%; 44/79) and K. oxytoca (50%; 3/6) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

MDR profile in bacterial isolates.

MDR indicates multidrug resistant.

ESBL production among E coli and Klebsiella spp

Among 103 E. coli and Klebsiella isolates, 28.2% (29/103) were confirmed as ESBL producers by combination disk diffusion method. The highest percentage of ESBL production was found among K. pneumoniae (33.3%; 6/18), followed by E. coli (27.9%; 22/79) and K. oxytoca (16.7%; 1/6) (Table 3).

Table 3.

ESBL production profile among Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp.

| Organisms | No. of isolates | ESBL producer |

|---|---|---|

| Confirmed (%) | ||

| E. coli | 79 | 22 (27.8) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 18 | 6 (33.3) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 6 | 1 (16.7) |

| Total | 103 | 29 (28.2) |

Abbreviation: ESBL, extended spectrum β-lactamase.

Distribution of ESBL producers according to different age of patient

Among the 103 isolates, 77.7% (n = 80) were isolated from children ⩽5 years age, followed by 6 to 10 years age group children (15.5%; n = 16). Of 103 bacterial isolates, 28.1% (n = 29) were ESBL producers and the most (82.8%; n = 24) were isolated from children ⩽5 years of age. There was no association between ESBL producers and age of patients (P < .05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of ESBL according to sex and age of children.

| Age groups, y | No. of isolates (%) | ESBL production | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ⩽5 | 80 (77.7) | 24 (82.8) | |

| 6-10 | 16 (15.5) | 4 (13.8) | .837* |

| 11-15 | 7 (6.8) | 1 (3.4) | |

| Total | 103 (100.0) | 29 (28.1) |

Abbreviation: ESBL, extended spectrum β-lactamase.

χ2 test.

Distribution of ESBL producers in different wards of hospitals

Of 29 isolates of ESBL producers, 51.7% (n = 15) were from inpatients, whereas 48.3% (n = 14) were from outpatient department. There was no significant association between ESBL production and type of the patients (P > .05) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Distribution of ESBL producers in different wards of hospitals.

| Wards | No. of isolates (%) | ESBL producer bacterial isolates (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatients | |||

| OPD | 52 (50.5) | 14 (48.3) | |

| Inpatients | .737* | ||

| ICU | 13 (12.6) | 5 (17.2) | |

| Other than ICU | 38 (36.9) | 10 (34.5) | |

| Total | 103 (100.0) | 29 (28.1) | |

Abbreviations: ESBL, extended spectrum β-lactamase; ICU, intensive care unit; OPD, outpatient department.

χ2 test.

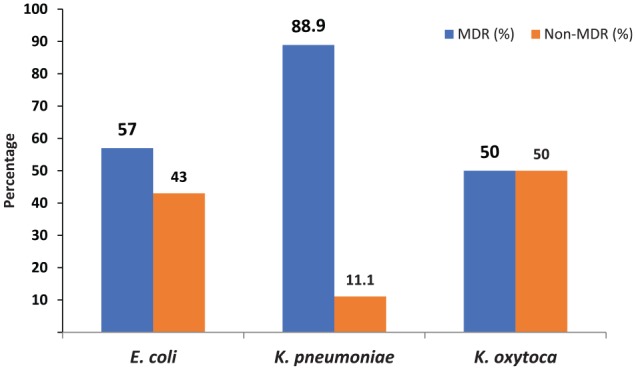

Antibiotic susceptible pattern of ESBL producers

All of ESBL producers’ isolates were found to be resistant toward cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, and ampicillin. Most ESBL producers were found to be susceptible toward imipenem (89.7%; 26/29), nitrofurantoin (82.8%; 24/29), piperacillin/tazobactam (79.3%; 23/29), and amikacin (72.4%; 21/29) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of ESBL producers.

ESBL indicates extended-spectrum β-lactamase.

Discussion

Overall findings

This study found the high prevalence (>60%) of MDR bacteria in clinical specimens isolated from the tertiary care hospital of children in Kathmandu valley. Among MDR isolates, half of the isolates were ESBL producers. Most ESBL-producing isolates were found to be resistant toward cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, and ampicillin. Similar findings were reported in previous studies in different clinical settings of Nepal.12,17,22,23

Most isolates (>80%) in this study were found susceptible to imipenem, piperacillin/tazobactam, and amikacin. The high efficacy of amikacin and imipenem against E. coli and Klebsiella was also reported from studies conducted in Chitwan24 and Lumbini,25 Nepal. The findings were also in line with a study from Manipal Teaching Hospital, Pokhara.11

Most isolates (77.5%) were resistant to ampicillin and more than half of the cephalosporin group of antibiotics. Similar findings were observed in a tertiary hospital in Pokhara, Nepal.11 This type of resistance could be due to the production of several β-lactamase enzymes. As ampicillin is the first-line β-lactam drug for Enterobacteriaceae, it can be easily hydrolyzed by β-lactamase enzymes. Resistance to fluoroquinolones is due to mutation at the target site, ie, gyrA (gyrase subunit gene) and parC (topoisomerase subunit gene) and efflux.26

The AMR, including MDR, is a global problem, and its burden varies between the regions; however, low- and middle-income countries share a disproportionate burden due to multitude of factors embedded in the characteristics of the health system, policy, and the practice.27 Moreover, MDR pathogens are more common in hospital settings and are mostly of nosocomial origin which is often difficult to treat.28 MDR pose a major threat in the management of uropathogens.29-31 More than two-thirds of the isolates in this study were MDR, mostly being E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and K. oxytoca. A high prevalence of MDR strains have been reported consistently from past studies from within Kathmandu10,12,17,28 and outside.8,14,16 Bacterial resistance to β-lactam antibiotics has risen dramatically, with significant contribution by ESBL.32

E. coli and K. pneumoniae are major ESBL producers posing serious threat to the treatment regimen.33 ESBL enzymes are becoming increasingly expressed by many strains of pathogenic bacteria presenting diagnostic challenges to the clinical microbiology laboratories.34 The highest bacterial isolates were found in children less than 5 years age, including the prevalence of ESBL organisms which was above 80%. The reason for this may be due to the immunological status of the children below 5 years of age who are more vulnerable to infections. The higher prevalence of bacterial growth in inpatients may have been added by nosocomial infections. Nosocomial infections are associated with prolonged hospital stay, intensive care unit admission, extensive use of invasive medical devices, and overconsumption of antibiotic among inpatients.35,36

Most ESBL organisms were susceptible to imipenem, piperacillin/tazobactam, amikacin, and nitrofurantoin. However, ESBL producers were resistant to ampicillin and cephalosporin group of antibiotics. These findings are consistent with similar studies reported from Nepal.11,33,37-39 The high proportion of resistance to third-generation cephalosporins reported for E. coli and K. pneumoniae means that treatment of severe infections likely to be caused by these bacteria in many settings must rely on carbapenems, the last resort to treat severe community- and hospital-acquired infections.40

Increasing spectrum of ESBL drug-resistant bacterial isolates can cause major problems for physicians in choosing from the available therapeutic options, if these organisms are not routinely isolated. Reporting of ESBL-producing isolates from clinical samples is thus critical for the clinicians to select appropriate antibiotics for the treatment, including to take proper precaution to prevent the spread of these resistant organisms to other patients.

Strengths and limitations

This study will be a useful reference for future studies to explore and expand on the wider prevalence of ESBL organisms in clinical and nonclinical settings. As our study was based on phenotypic detection of AMR and ESBL production that excluded identification and characterization of wide sorts of lactamases and pathogenic strains, genotypic characterization is recommended in future studies.

Implications for AMR and its control

This study has identified one of the major determinants of burgeoning AMR in Nepal. All antibiotics are available over the counter (OTC) in Nepal without medical prescriptions, and this is a major challenge as it contributes to antibiotic pressure and development of resistance.27,41 The availability of OTC antibiotics and its consumption before arriving to hospitals may also confound the clinical presentation, including general culture and sensitivity tests.27 Thus, cautious evaluation of preceding treatment history, combined with strong suspicion for ESBL and MDR and its diagnosis, may inform the appropriate treatment.11,16 The findings in this study warrant a relevant stakeholder’s engagement to strengthen the health policy to rationalize the use of antibiotics, including promoting diagnostic-based antibiotic prescriptions.42 Specifically, in pediatric patients with UTIs, it is critical to establish the diagnosis of ESBL organisms before initiating the antibiotic treatment.

Conclusion

A high prevalence of MDR ESBL organisms was found among pediatric patients in this study. Identification of ESBL producers in routine treatment of infectious diseases in pediatric patients can reduce unnecessary and inappropriate antimicrobial use. Hospitals treating infectious diseases can benefit by integrating antimicrobial stewardship programs to combat the emergence of AMR and ESBLs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude and admiration to all the staffs and faculties of Central Department of Microbiology, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, and International Friendship Children’s Hospital, Kathmandu, for their support and guidance to complete this study. We are thankful to pediatric patients and their parents to support in the study.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All the authors made substantial contribution to the study. K.K. and B.D. conceived and designed the study. K.K. collected samples, investigated, and recorded the laboratory findings. K.R.R., S.K., M.R.B., and P.G. advised and formulated the methodology for the study. K.R.R. and B.A. are responsible for reviewing several versions of the article. Others helped to review and amend this article. All authors read and approved the final article.

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Departmental fund of Central Department of Microbiology, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data pertaining to this study are within the article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Institutional Review Committee of Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) approved this research. Written consent was applicable to literate people while verbal consent was approached for the rest subjects. Parents/Guardians were interviewed in case of children. Strict adherence to the ethical guidelines was taken, and we declare that this research is free from selection bias.

ORCID iD: Komal Raj Rijal  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6281-8236

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6281-8236

References

- 1. Afzal AMS. Antibiotic resistant pattern of E. coli and Klebsiella species in Pakistan: brief overview. J Microb Biochem Tech. 2017;9:6. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kibret M, Abera B. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of E. coli from clinical sources in northeast Ethiopia. Afr Health Sci. 2011;11:S40-S45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Podschun R, Ullmann U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev.1998;11:589-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Allocati N, Masulli M, Alexeyev MF, Di Ilio C. Escherichia coli in Europe: an overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:6235-6254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peirano G, Pitout JD. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli producing CTX-M beta-lactamases: the worldwide emergence of clone ST131 O25:H4. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35:316-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bakshi P, Walia GSJ. Prevalence of extended spectrum β-lactamase in multidrug-resistant strains of gram negative bacilli. J Acad Indus Res. 2013;1:558-560. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Upadhyay A, Parajuli P. Extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL)-producing Klebsiella species isolated at National Medical College and Teaching Hospital Nepal. Asian J Pharma and Clin Res. 2013;1:161-164. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thenmozhi S, Moorthy K, Sureshkumar B, Suresh M. Antibiotic resistance mechanism of ESBL producing enterobacteriaceae in clinical field: a review. Int Pure App Biosci. 2014;2:207-226. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Neupane S, Pant ND, Khatiwada S, Chaudhary R, Banjara MR. Correlation between biofilm formation and resistance toward different commonly used antibiotics along with extended spectrum beta lactamase production in uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from the patients suspected of urinary tract infections visiting Shree Birendra Hospital, Chhauni, Kathmandu, Nepal. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016;5:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Raut S, Gokhale S, Adhikari B. Prevalence of extended spectrum beta-lactamases among E. coli and Klebsiella spp isolates in Manipal, Teaching Hospital, Pokhara, Nepal. JMID. 2015;5:69-75. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nepal K, Pant ND, Neupane B, et al. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase and metallo beta-lactamase production among Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from different clinical samples in a tertiary care hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2017;16:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rai S, Pant ND, Bhandari R, et al. AmpC and extended spectrum beta-lactamases production among urinary isolates from a tertiary care hospital in Lalitpur, Nepal. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shrestha S, Amatya R, Dutta R. Prevalence of extended spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL) production in gram negative isolates from pyogenic infection in tertiary care hospital of eastern Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2011;13:186-189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sharma KR, Bhandari P, Adhikari N, Tripathi P, Khanal S, Tiwari BR. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing multi drug resistant (MDR) Urinary pathogens in a children hospital from Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2018;16:151-155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Raut S, Adhikari B. ESBL and their identification in peripheral laboratories of Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2015;17:176-181. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parajuli NP, Maharjan P, Parajuli H, et al. High rates of multidrug resistance among uropathogenic Escherichia coli in children and analyses of ESBL producers from Nepal. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. American Society for Microbiology. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ramadan D, Bassyani E, Amer M, Emam S. Detection of ESBL producing bacteria in cases of UTI in pediatric department of Benha university hospital. Egyptian J Med Microbiol. 2016;25:77-84. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Forbes BA, Sahm FD, Weissfelt SA. Bailey & Scott’s Diagnostic Microbiology. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Publications, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (M100S). Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shrestha D, Shrestha SP, Gurung K, Manandhar S, Sherchan S. Prevalence of Multidrug resistant Extended Spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL)-producing bacteria from different clinical specimens in Kathmandu Model Hospital, Kathmandu Nepal. EC Microbiol. 2016;4:676-698. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shakya P, Shrestha D, Maharjan E, Sharma VK, Paudyal R. ESBL production among E. coli and Klebsiella spp. causing urinary tract infection: a hospital based study. Open Microbiol J. 2017;11:23-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gautam R, Chapagain ML, Acharya A, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Escherichia coli from various clinical sources. J Chit Med Coll. 2013;3: 14-27. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lamichhane B. Antibiotic resistance patterns of Gram-negative isolates in a tertiary care hospital of Nepal. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2014;7:30-33. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ozeki S, Deguchi T, Yasuda M, et al. Development of a rapid assay for detecting gyrA mutations in Escherichia coli and determination of incidence of gyrA mutations in clinical strains isolated from patients with complicated urinary tract infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2315-2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pokharel S, Raut S, Adhikari B. Tackling antimicrobial resistance in low- and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4:e002104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mishra SK, Awal BK, Kattel HP, et al. Drug resistant bacteria are growing menace in a University Hospital in Nepal. American J Epidem Infec Dis. 2014;2:19-23. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tankhiwale SS, Jalgaonkar SV. Evaluation of extended spectrum beta-lactamases in urinary isolates. Indian J Med Res. 2004;12:1005-1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Akram M, Shahid M, Khan AU. Etiology and antibiotic resistance patterns of community-acquired urinary tract infections in JNMC Hospital Aligarh, India. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2007;6:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hasan AS, Nair D. Resistance patterns of urinary isolates in a tertiary Indian hospital. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2007;19:39-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kulkarni DM, Badrapurkar SA, Nilekar SL, More SR. Prevalence of extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing E. coli and Klebsiella species in urinary isolates. J Dental Med Sci. 2016;15:26-29. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rimal U, Thapa S, Maharajan R. Prevalence of Extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species from urinary specimens of children attending Friendship International Children’s Hospital. Nep J Biotech. 2017;5:32-38. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sharma AR, Bhatta DR, Shrestha J, Banjara MR. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Escherichia coli isolated from urinary tract infected patients attending Bir Hospital. Nepal J Sci Tech. 2013;14:177-184. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jacoby GA. AmpC beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:161-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rupp ME, Fey PD. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae: considerations for diagnosis, prevention and drug treatment. Drugs. 2003;63:353-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chander A, Shrestha CD. Prevalence of extended spectrum beta lactamase producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae urinary isolates in a tertiary care hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ansari S, Nepal HP, Gautam R, et al. Community acquired multi-drug resistant clinical isolates of Escherichia coli in a tertiary care center of Nepal. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015;4:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guragain N, Pradhan A, Dhungel B, Banjara MR, Rijal KR, Ghimire P. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Gram negative bacterial isolates from urine of patients visiting Everest Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal. TUJM. 2019;6:26-31. [Google Scholar]

- 40. World Health Organization (WHO). Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Raut S, Adhikari B. Ceftazidime-avibactam in ceftazidime-resistant infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Raut S, Adhikari B. Global leadership against antimicrobial resistance ought to include developing countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]