Abstract

The following fictional case is intended as a learning tool within the Pathology Competencies for Medical Education (PCME), a set of national standards for teaching pathology. These are divided into three basic competencies: Disease Mechanisms and Processes, Organ System Pathology, and Diagnostic Medicine and Therapeutic Pathology. For additional information, and a full list of learning objectives for all three competencies, see http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2374289517715040.1

Keywords: pathology competencies, organ system pathology, hematopathology, myeloid neoplasia, acute myeloid leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, myeloproliferative neoplasms

Primary Learning Objective

Objective HWC3.2: Myeloid Neoplasia. Compare and contrast myelodysplastic syndrome, myeloproliferative neoplasm, and acute myeloid leukemia with respect to morphologic appearance, clinical features, and underlying pathophysiology.

Competency 2: Organ System Pathology. Topic: (HWC) Hematopathology—White Cell Disorders; Learning Goal 3: Classification of Leukemia and Lymphomas.

Secondary Learning Objective

Objective HWC3.4: Morphology of Acute Versus Chronic Leukemia. Discuss the morphologic appearance of a blast and be able to distinguish acute myeloid leukemia from chronic myeloid leukemia.

Competency 2 Organ System Pathology; Topic: (HWC) Hematopathology—White Cell Disorders; Learning Goal 3: Classification of Leukemia and Lymphomas

Patient Presentation

The patient is a 36-year-old female who presents to the emergency department with fatigue, malaise, anorexia, body aches, lightheadedness, and headaches. Her medical history is significant for a previous diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) after chemotherapy. She reports having achieved remission last year.

Diagnostic Findings, Part 1

On physical examination, there is pallor of her conjunctiva, nail beds, and oral mucosa. In addition, she has small petechiae on her upper and lower extremities. No splenomegaly or other significant physical examination findings are noted.

Question/Discussion Points, Part 1

Given This Patient’s Clinical Presentation and Past Medical History, What Are Our Top Differential Diagnoses?

Symptoms such as fatigue, malaise, anorexia, body aches, lightheadedness, and headaches are constitutional symptoms and are nonspecific, as they can be attributed to a large array of diseases. However, due to the patient’s past medical history, the first differential diagnosis that should be considered is relapse of her AML. Other differential diagnoses include infection, autoimmune disorders, endocrine disorders, and nutritional deficiencies.

What Is the Clinical Presentation of Myeloid Disorders?

The patient’s clinical presentation is generally a result of the changes in the 3 hematopoietic cell lineages attributed to infiltration of the blasts in the bone marrow. Patients can experience fatigue secondary to anemia, bleeding and easy bruising secondary to the thrombocytopenia, and fever and infection secondary to the lack of functioning leukocytes. Myelodysplastic syndrome and myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) can also have the same presentation, depending on the affected cell line. Therefore, the clinical presentation is generally not useful in the identification of this group of malignancies.

What Are Some Initial Diagnostic Laboratory Tests That Should be Ordered for This Patient?

The most important laboratory value in this patient is her complete blood count (CBC), as these results can prompt further investigation for AML relapse. In patients with AML, the white blood cell count (WBC) can be normal, elevated, or reduced. However, patients usually experience anemia and thrombocytopenia. Other laboratory test results that might be of clinical value include complete metabolic panel; renal function tests such as blood urea nitrogen and creatinine (Cr); liver function tests such as alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase; thyroid function tests such as thyroid-stimulating hormone, T3, and T4; antinuclear antibodies; C-reactive protein; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; vitamin B12 levels; and folic acid levels.

Diagnostic Findings, Part 2

The patient’s CBC showed a WBC of 3500/mcL with 27% blasts, a hemoglobin (Hb) level of 4.3 g/dL, and a platelet count of 20 000/mcL. A peripheral smear examination revealed blasts that were large in size with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, prominent nucleoli, and no cytoplasmic granules or Auer rods (Figure 1).

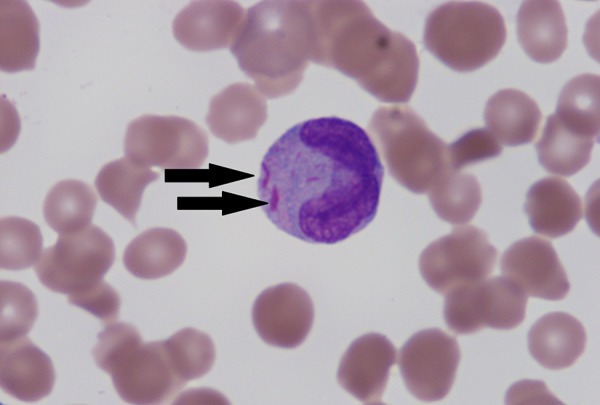

Figure 1.

This peripheral blood smear reveals the presence of large blasts with fine chromatin and prominent nucleoli. One nucleated red blood cell is present (arrow) (×400).

Question/Discussion Points, Part 2

What Is Significant About the CBC and Peripheral Smear Findings?

With a low WBC, Hb, and platelet count, this patient has pancytopenia. Patients with a history of a hematopoietic malignancy and pancytopenia should be worked up for potential relapse or infection. The presence of 27% blasts on peripheral smear is diagnostic of AML relapse.

With the Presence of Blasts on the Peripheral Blood Smear, What Are Our Top Differentials?

The presence of blasts on a peripheral blood smear is usually an abnormal finding, unless it is a physiological response; such situations where blasts can be identified include patients taking granulocyte colony stimulating factor, newborns, and leukemoid reactions (eg, due to overwhelming sepsis).2 When these physiological situations have been ruled out as a potential cause for the identification of blasts on peripheral smear, further evaluation must be done to rule out a hematopoietic malignancy. First, the analysis of these blasts by flow cytometry must be utilized to differentiate the origin of these blasts as myeloid or lymphoid (Table 1). From the myeloid lineage, the top differentials should include AML, MPNs, myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and MDS/MPN.

Table 1.

Flow Cytometric Markers for the Differentiation of Myeloid Versus Lymphoid.*

| Myeloid Markers | Lymphoid Markers | Nonspecific Markers |

|---|---|---|

| Myeloperoxidase (MPO), CD11b, CD11c, CD13, CD14, CD15, CD16, CD33, CD36, CD64, CD117 |

T cells: CD1a, CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7, CD8 B cells: CD10, CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a |

CD38, CD34, CD45, CD56, HLA-DR, Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TDT) |

* Please note that in hematopoietic malignancies, neoplastic cells can abnormally express markers that are not typically expressed in their cell lineage.

Of these myeloid neoplasms, the presence of blasts warrants a diagnosis of AML. Myeloproliferative neoplasms consist of the disease entities known as chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), chronic neutrophilic leukemia, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocytopenia, primary myelofibrosis, chronic eosinophilic leukemia not otherwise specified, and myeloproliferative neoplasm, unclassifiable.3

Myelodysplastic syndromes can be further subclassified into MDS with single lineage dysplasia, MDS with multilineage dysplasia, MDS with ring sideroblasts, MDS with excess blasts (EB), MDS with isolated 5q deletion, and MDS unclassifiable. The subclassification of MDS-EB1 or MDS-EB2 depends on the percentage of blasts present on the peripheral blood or bone marrow.4

Finally, the subgroup MDS/MPN consists of the following entities: chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), atypical CML, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, MDS/MPN with ring sideroblasts and thrombocytosis, and MDS/MPN unclassifiable. Blasts can be identified in all of these neoplasms, but the percentage in the peripheral blood and bone marrow must be <20%, as the presence of >20% blasts will satisfy the diagnostic criteria for AML.5 However, the prevalence of these neoplasms is much lower than the former 2 categories and therefore should be lower on the list of differentials. Therefore, the presence of aberrant blasts of myeloid origin should lead to further evaluation for MDS-EB1, MDS-EB2, CML blast phase, and AML.

What Is the Diagnostic Criteria for Acute Myeloid Leukemia?

Acute myeloid leukemia is a characterized by an abnormal proliferation of blast cells that can be seen in the peripheral blood and/or bone marrow. The diagnosis of AML requires the presence of ≥20% blasts or the presence of the following cytogenetic abnormalities: t(8;21), t(15;17), t(16;16), or inv(16).6

What Is the Typical Morphology for Acute Myeloid Leukemia and How Would You Distinguish Acute Myeloid Leukemia From Myelodysplastic Syndromes?

The classic morphology for AML requires the identification of blasts. A blast can be described as an immature cell with a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, fine dispersed chromatin, with a single or multiple prominent nucleoli (Figure 1). Some variants of AML will have small pink granules or Auer rods in the cytoplasm (Figure 2). The presence of these Auer rods can be a medical emergency and should raise a high suspicion for acute promyelocytic anemia (APL). These patients should be evaluated for disseminated coagulation (DIC), cytogenetics for t(15;17), and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for the promyelocytic leukemia (PML)-retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARA) fusion protein. The placement of these patients on all trans retinoic acid can be lifesaving.7

Figure 2.

The peripheral blood smear reveals a myeloid cell with several pink Auer rods (arrow) within the cytoplasm (×1000).

The blast percentage is the best modality to determine whether a patient has AML or MDS. As stated earlier, the diagnosis of AML requires the presence of ≥20% blasts in the peripheral blood or bone marrow, whereas the presence of blasts ≤19% suggests the diagnosis of MDS. This can be further subclassified into MDS-EB1, where blasts account for <5% of leukocytes in the peripheral blood and <10% in the bone marrow and MDS-EB2, where blasts comprise 5% to 19% of WBCs in the peripheral blood and 10% to 19% in the bone marrow. The presence of Auer rods, regardless of blast count, will also require the designation of MDS-EB2.

In addition to a lower blast percentage, MDS requires at least one of the following Hb <10 g/dL, platelets <100 000 or absolute neutrophil count <1800, and dysplasia present in at least 1 lineage. Dysplastic features of red blood cells include budding, internuclear bridges, karyorrhexis, multinucleation, megaloblastic appearance, or vacuolization. Dysplastic megakaryocytes include micromegakaryocytes or megakaryocytes with naked nuclei, separated nuclei, or nonlobated nuclei. Dysplastic leukocytes are the least common, and some features can include nuclear hyposegmentation and hypogranulatation. It is important to note that dysplasia is present only in MDS and not commonly seen in MPNs.

How Would You Distinguish Acute Myeloid Leukemia From Chronic Myeloid Leukemia?

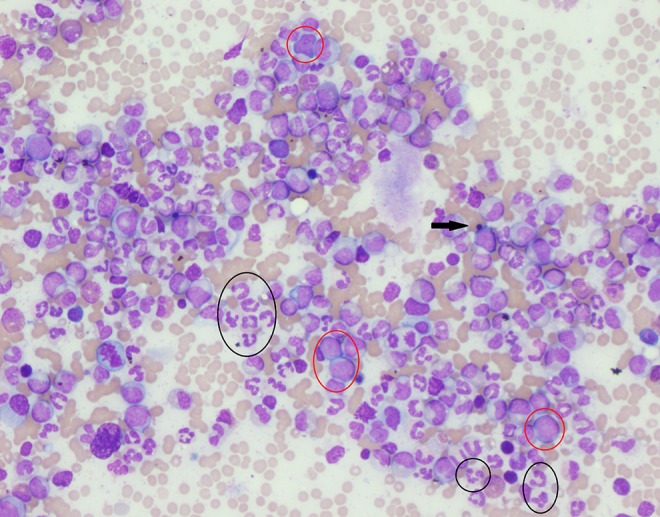

Unlike AML, CML chronic phase presents with leukocytosis composed of mostly mature segmented neutrophils and less prominence of blasts (Figure 3). Chronic myeloid leukemia can present in 3 different phases, chronic, accelerated, and blast phase, with the most common phase being the chronic phase. The chronic phase is characterized by leukocytosis with basophilia, eosinophilia, monocytosis, normal or increased platelets, and nucleated red blood cells on the peripheral blood smear. A bone marrow biopsy will reveal a hypercellular marrow with a myeloid to erythroid ratio of 10 to 1 (Figure 4). The diagnosis of CML requires the detection of the Philadelphia chromosome t(9;22) by cytogenetic studies or the identification of BCR-ABL1 by either FISH or polymerase chain reaction (PCR).8 The blast phase/crisis requires the presence of at least >20% blasts; should this occur during the course of a patient’s disease, their CML has progressed into an AML.

Figure 3.

The peripheral blood smear reveals marked leukocytosis with predominant segmented neutrophils (circled in black). Rare blasts can also be identified (circled in red). One nucleated red blood cell is present (arrow) (×200).

Figure 4.

The hematoxylin and eosin section of the bone marrow biopsy reveals a hypercellular marrow with numerous mature segmented neutrophils (circled in black) (×200).

With the Complete Blood Count and Peripheral Blood Smear Findings, What Is the Next Best Step for Management?

The next best step in the management of this patient would be to consult the hematology oncology team and schedule a bone marrow biopsy. Her bone marrow aspirate and biopsy are shown in Figures 5 and 6. What are some findings that are noted on histology?

Figure 5.

The bone marrow aspirate smear reveals numerous blasts and 5 prominent mast cells, 1 with normal morphology (circled in black) and 4 of which are atypically spindle shaped (circled in red) (×400).

Figure 6.

The hematoxylin and eosin section reveals a hypercellular marrow with gray aggregates of mast cells (circled in black) among neoplastic blasts (circled in red) (×200).

Diagnostic Findings, Part 3

Her bone marrow biopsy is hypercellular (85%-90%) with 95% blasts and multiple aggregates of mast cells that are round with abundant purple granules within the cytoplasm. Subsets of these mast cells are abnormally spindle-shaped on bone marrow aspirate smears (Figures 5 and 6). Immunohistochemical stains reveal that the blasts were positive for CD117, a normal marker for hematopoietic stem cells. Due to the abnormally increased presence of mast cells, further investigation is pursued as patients with AML can develop a neoplastic proliferation of mast cells associated with their leukemia.

Immunohistochemical stains with CD117, CD25, and tryptase are positive in the mast cells, whereas CD2 is negative in the mast cells. While normal mast cells typically stain positive for CD117 and tryptase, the expression of CD2 and CD25 indicates aberrancies, resulting in a high suspicion for a neoplastic proliferation. Therefore, the bone marrow findings are consistent with a recurrent AML and newly diagnosed systemic mastocytosis; this combination of diseases is known as systemic mastocytosis with AML.

Question/Discussion Points, Part 3

What Is the Diagnostic Criteria for Systemic Mastocytosis?

According to the World Health Organization, the diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis can be made when the major criterion and at least 1 minor criterion are present, or when ≥3 minor criteria are present.9

The major criterion includes abnormal dense infiltrates of clonal mast cells (≥15 mast cells in aggregates) detected in sections of bone marrow and/or other organs.

There are 4 minor criteria:

In biopsy sections of bone marrow or other organs, >25% of the mast cells in the infiltrate are spindle-shaped or have atypical morphology or >25% of all mast cells in bone marrow aspirate smears are immature or atypical.

Detection of an activating point mutation at codon 816 of KIT (c-kit).

Mast cells in the bone marrow, blood, or another extracutaneous organ that express aberrant CD25 or CD2, in addition to normal mast cell markers.

Serum total tryptase is persistently >20 ng/mL. If there is an associated myeloid neoplasm, this parameter is not valid.

What Is the Diagnostic Criteria for Systemic Mastocytosis With an Associated Hematological Neoplasm?

In order to diagnose Systemic Mastocytosis with an Associated Hematological Neoplasm (SMAHN), the case must meet the general criteria for systemic mastocytosis and also meet the criteria for an associated hematological neoplasm (ie, a myelodysplastic syndrome, myeloproliferative neoplasm, AML, lymphoma, or another hematological neoplasm). The most common hematological malignancies associated with systemic mastocytosis is CMML.10

What Is the Typical Presentation for Mastocytosis?

Mastocytosis can present with a large variety of symptoms. The most common manifestation is skin involvement. Constitutional symptoms such as weight loss and fatigue can also be seen. Mast cells can also cause mediator-related events such as abdominal pain, headache, hypotension, syncope, tachycardia, respiratory symptoms, and musculoskeletal symptoms.11 The severity of the symptoms can range up to multiorgan failure.

Now That the Patient Has Systemic Mastocytosis Associated With a Hematological Neoplasm, Are There Any Other Investigational Studies That Should be Performed?

In addition to histological evaluation and flow cytometry analysis, molecular studies are routinely performed for hematopoietic malignancies.

Diagnostic Findings, Part 4

Fluorescence in situ hybridization of her new bone marrow aspirate sample detects t(8;21), consistent with a recurrent AML. In addition, a new c-KIT mutation is identified at exon D816V, confirming the diagnosis of a systemic mastocytosis.

Question/Discussion Points, Part 4

What Is the Role of c-Kit (CD117)?

The c-kit mutation is found in most cases of systemic mastocytosis, and in many cases, it is detectable not only in the mast cells but also in the malignant cells within the associated hematological malignancy (eg, AML blasts or CMML monocytes). The c-kit gene encodes for a protein, KIT (CD117), which contains tyrosine kinase activity that functions as a growth factor and promotes clonal proliferation and progression. In addition, it can help with survival advantages in the malignant cells. Medications such as imatinib, nilotinib, and dasitinib have been developed to target the KIT protein; for mastocytosis, dasitinib is the most specific drug as it targets the D816V mutation.12

What Is the Pathophysiology of Myeloproliferative Neoplasms and Myelodysplastic Syndromes?

A normal bone marrow should have varying proportions of cells in the myeloid lineage starting from myeloblasts and ranging in maturation to mature segmented neutrophils. The pathogenesis of MPNs results from multiple gene mutations or rearrangements; these alterations can lead to clonal transformation of myeloid cells. Acute myeloid leukemia is a result of the abnormal proliferation of myeloid stem cell precursors. Generally, AML is the result of 2 separate genetic mutations, where one mutation will lead to proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells and increased survival advantage and the other mutation results in arrested cell differentiation and apoptosis.13 The second hit results in the abnormally large presence of blasts with limited maturation of cells. Other MPNs have a similar pathophysiology as AML with the difference being maturational capability of the clonal cells; this ability to mature results in the predominance of mature neoplastic cells as opposed to blasts.

Myelodysplastic syndromes result from the ineffective production of at least 1 cell lineage in the bone marrow. This ineffective hematopoiesis results in bone marrow hyperplasia. Although the bone marrow is overproducing cells, these cells are dysfunctional, resulting in the decreased release of cells into the peripheral blood.14 A reduced population of hematopoietic cells is referred to as a “cytopenia.” This cytopenia can be reflected in the CBC as an anemia, leukopenia, and/or thrombocytopenia.

Teaching Points

The presence of blasts on a peripheral blood smear should warrant the analysis of these blasts by flow cytometry to differentiate the lineage of these blasts as myeloid or lymphoid. From the myeloid lineage, the top differentials should include AML, MDS, MPN, and MDS/MPN.

The patient’s clinical presentation in myeloid neoplasms generally is a result of the changes in the 3 hematopoietic cell lineages secondary to infiltration of the blasts in the bone marrow. Patients can experience fatigue secondary to the anemia, bleeding, and easy bruising attributed to the thrombocytopenia, and infection from the lack of functioning leukocytes.

Acute myeloid leukemia is characterized by an abnormal proliferation of myeloid precursors. The diagnosis of AML requires the presence of ≥20% blasts in the peripheral blood and/or bone marrow or the presence of the following cytogenetic abnormalities: t(8;21), t(15;17), t(16;16) or inv(16).

The presence of Auer rods is a medical emergency and should raise a high suspicion for APL. These patients should be evaluated for DIC, cytogenetics for t(15;17), and FISH for the PML-RARA fusion protein. The placement of these patients on all trans retinoic acid can be lifesaving.

The presence of abnormal or dysplastic cells highly suggests the diagnosis of MDS as dysplasia is not profoundly seen in other entities. Myelodysplastic syndromes requires at least one of the following: Hb <10 g/dL, platelets <100 000 or absolute neutrophil count <1800, and dysplasia present in at least 1 lineage. In MDS-EB1, blasts account for <5% of leukocytes in the peripheral blood and <10% in the bone marrow and in MDS-EB2, blasts comprise 5% to 19% of WBCs in the peripheral blood and 10% to 19% in the bone marrow. The presence of Auer rods will also require the designation of MDS-EB2.

Chronic myeloid leukemia can present in 3 different phases. The chronic phase is characterized by leukocytosis with left shifted neutrophils, basophilia, eosinophilia, monocytosis, normal or increased platelets, and blasts <10% on the peripheral blood smear.

The diagnosis of CML requires the detection of the Philadelphia chromosome t(9;22) by cytogenetic studies or the identification of BCR-ABL1 by either FISH or PCR.

The diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis can be made when the major criterion and at least 1 minor criterion are present or when ≥3 minor criteria are present. The major criterion involves abnormal dense infiltrates of clonal mast cells. The 4 minor criteria include (1) >25% of all mast cells are immature, spindled, or atypical; (2) detection of a mutation at codon D816V of KIT (c-kit); (3) aberrant CD2 or CD25 expression; and (4) tryptase levels >20 ng/mL.

While normal mast cells typically stain positive for CD117 and tryptase, the aberrant expression of CD2 and or CD25 is suggestive of aberrancies, a neoplastic clonal proliferation.

The c-kit mutation at exon D816V for the KIT protein is found in most cases of systemic mastocytosis. The presence of this mutation can aid in the selection of therapeutic agents.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Brenda Mai  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4767-1293

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4767-1293

References

- 1. Knollmann-Ritschel BEC, Regula DP, Borowitz MJ, Conran R, Prystowsky MB. Pathology competencies for medical education and educational cases. Acad Pathol. 2017:4 doi:10.1177/2374289517715040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dasgupta A, Wahed A. Hematology and Coagulation—A Comprehensive Review for Board Preparation. New York, NY: Elsevier Science Publishing Co; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vardiman JW, Melo JV, Baccarani M, et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasms In: Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris NL, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues Revised. 4th ed Lyon: IARC Press; 2017:29–60. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hasserjian RP, Orazi A, Brunning RD, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes: overview In: Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris NL, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues Revised. 4th ed Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2017:97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Orazi A, Bennet JM, Germing U, et al. Myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms In: Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris NL, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues Revised. 4th ed Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2017:81–96. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arber DA, Brunning RD, Le Beau MM, et al. Acute myeloid leukaemia and related precursor neoplasms In: Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris NL, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues Revised. 4th ed Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2017:129–170. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sanz MA, Grimwade D, Tallman MS, et al. Management of acute promyelocytic anemia: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European leukemia net. Blood. 2009;113:1875–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Testoni N, Marzocchi G, Luatti S, et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia: a prospective comparison of interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization and chromosome banding analysis for the definition of complete cytogenetic response: a study of the GIMEMA CML WP. Blood. 2009;114:4939–4943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Horny HP, Akin C, Arber DA. Mastocytosis In: Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris NL, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues Revised. 4th ed Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2017:61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Valent P, Akin C, Metcalfe DD. Mastocytosis: 2016 updated WHO classification and novel emerging treatment concepts. Blood. 2017;129:1420–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arock M, Wedeh G, Hoermann G, et al. Preclinical human models and emerging therapeutics for advanced systemic mastocytosis. Haematologica. 2018;103:1760–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cruse G, Metcalfe DD, Olivera A. Functional deregulation of KIT: link to mast cell proliferative diseases and other neoplasms. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014;34:219–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nichol JN, Assouline S, Miller WH. Neoplastic Diseases of the Blood. New York, NY: Springer; 2013: 177–198. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Visconte V, Tiu RV, Rogers HJ. Pathogenesis of myelodysplastic syndromes: an overview of molecular and non-molecular aspects of the disease. Blood Res. 2014;49:216–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]