Structured Abstract

Objective:

To determine the episodes of care during which opioid-naïve patients receive initial opioid prescriptions. We hypothesized that the percentage of prescriptions to surgical, emergency medicine, and dental patients increased as new primary care and pain medicine opioid prescribing guidelines were developed.

Summary Background Data:

Most opioid-related morbidity and mortality derives from prescribed opioids or from nonmedical opioid misuse and abuse stemming from prescription use. Although guidelines exist for opioid prescribing in the setting of chronic use, much less is known regarding the types of care for which opioid-naïve patients are provided an initial opioid prescription.

Methods:

Retrospective cross-sectional study over 2010–2016 using a nationwide insurance claims dataset to study US adults aged 18 to 64 years. The primary outcome was change in opioid prescriptions for opioid-naïve patients undergoing surgical, emergency, and dental care from 2010 to 2016, and the type and amounts of opioid filled.

Results:

We identified 16,292,018 opioid prescriptions filled by opioid-naïve patients. The combined share of prescriptions for patients receiving surgery, emergency, and dental care increased by 15.8% from 2010 to 2016. In 2016, surgery patients filled 22.0% of initial prescriptions, emergency medicine patients 13.0%, and dental patients 4.2%; surgical patients received the most total (403 mg oral morphine equivalents, SD 1369) and daily (82 mg oral morphine equivalents, SD 273) opioid amounts, and the second-highest number of days of opioid per prescription (5.4, SD 3.4). Surgical patients’ mean total oral morphine equivalents per prescription increased from 240 mg (SD 509) in 2010 to 403 mg (SD 1369) in 2016. Over the study period, surgical patients received the highest proportion of potent opioids (90.2%).

Conclusions:

Initial opioid prescribing attributable to dental, emergency, and surgical care is increasing relative to primary and chronic pain care, possibly due to the advent of opioid prescribing guidelines for primary care and pain physicians. These data emphasize the importance of developing prescribing guidelines for these episodes of care, during which the highest amounts of opioids are prescribed to opioid-naïve patients.

Mini-Abstract

For what types of care are opioid-naïve patients prescribed opioids? Among opioid-naive patients, we observed a 15.8% increase in the proportion of opioid prescriptions filled following surgical, dental, and emergency care from 2010 to 2016. Such care episodes are responsible for a rising proportion of opioid prescribing to opioid-naïve patients and should be the focus of efforts to create best practice guidelines.

INTRODUCTION

Opioid abuse is a major contributor to mortality in the United States, with 42,249 deaths attributed to opioid overdose in 2016.1 Opioid prescribing by clinicians has come under considerable scrutiny as an iatrogenic driver of the opioid crisis.2, 3 Prior research regarding opioid prescribing patterns has largely centered on chronic opioid users4–6 or patients with adverse outcomes.7, 8 Much less is known regarding the episodes of care responsible for initial opioid prescribing to opioid-naïve patients. We hypothesized that the share of initial prescriptions written to surgical, emergency medicine, and dental patients has increased over recent years, given research9, 10 and prescribing guidelines11 focused on primary care and pain physicians.

METHODS

The Truven Health MarketScan Commercial and Dental databases comprise a national, employer-based dataset of insurance and pharmacy claims. We queried pharmacy claims for prescription opioids from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2016 among adults aged 18 to 64 years to identify prescriptions filled by opioid-naïve patients (defined as no opioid prescriptions filled during the 365 days before the index fill). The study was exempt from review by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board; informed consent was waived due to the dataset’s deidentified nature.

To identify initial opioid prescriptions, we examined pharmacy claims for opioid fulfillments. We retrospectively examined claims over 1 year and excluded patients for whom any other opioid had been filled during this time period. Subsequently, we examined inpatient, outpatient, and dental billing data from ≤3 days prior to the remaining index fills. We classified prescriptions into the following groups using Current Dental Terminology, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-9) codes, as well as the Surgery Flag software of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ): dental, surgery, emergency medicine, and “other”. Separately, we determined whether any chronic pain ICD-9 codes were recorded within 365 days prior to each index fill. For each fulfillment, we also extracted the opioid prescribed, total oral morphine equivalents (OMEs), daily OMEs, and days of opioid supplied. Comprehensive details are in the Supplemental Digital Content.

Our primary outcome was the change in proportion of initial opioid prescriptions provided to opioid-naïve surgery, emergency medicine, and dental patients per year. This outcome was defined a priori prior to data extraction. We examined percentages of initial prescriptions rather than absolute numbers to account for the varying number of opioid naïve patients each year. Secondary outcomes included total OMEs filled per group per year, daily OMEs filled per group per year, days of opioid supplied per group per year, and opioid potency prescribed per group. Potent opioids were defined as hydrocodone and oxycodone, as compared to codeine, tramadol, and other opioids. We calculated descriptive statistics using SAS version 9.4.

RESULTS

We identified a total of 16,292,018 initial opioid prescriptions to opioid-naïve patients.

Initial Opioid Prescribing to Opioid-Naïve Patients by Patient Group

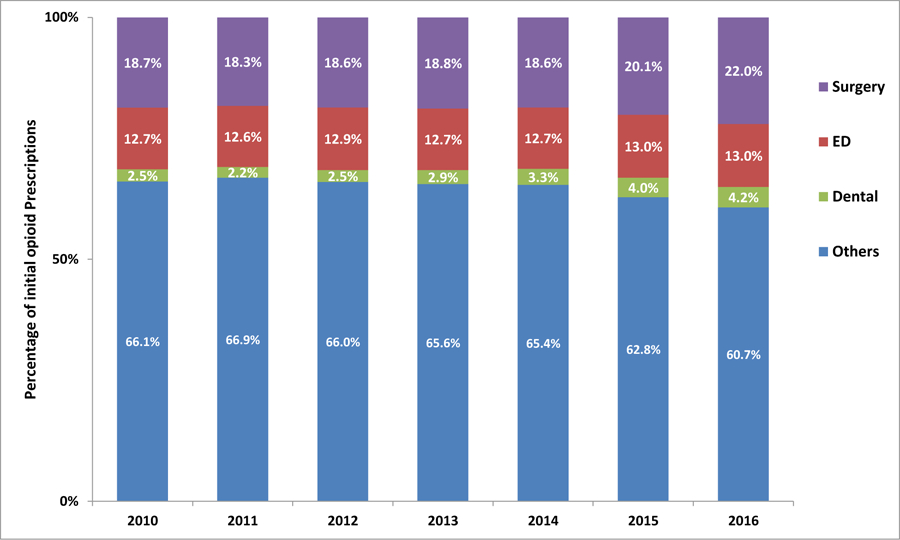

The combined percentage of surgery, emergency medicine, and dental prescriptions increased from 33.9% in 2010 to 39.3% in 2016, an 15.8% increase (Figure 1; Table in the Supplemental Digital Content). Surgery patients received the majority of prescriptions in the combined group each year, followed by emergency medicine and dental patients. The emergency medicine prescription share remained relatively constant, while the surgery and dental prescription shares increased. In total, 53.4% of all initial opioid prescriptions were to patients with a chronic pain diagnosis during the prior year (Table 2 in the Supplemental Digital Content). Surgical patients carried the highest proportion of chronic pain diagnoses (62.0%), followed by emergency medicine (52.6%) and “other” (51.8%). 36.1% of dental patients carried chronic pain diagnoses.

Figure 1.

The combined percentage of initial opioid prescriptions to surgical, emergency medicine, and dental patients is increasing.

Amount of Initial Opioid Prescribed by Patient Group

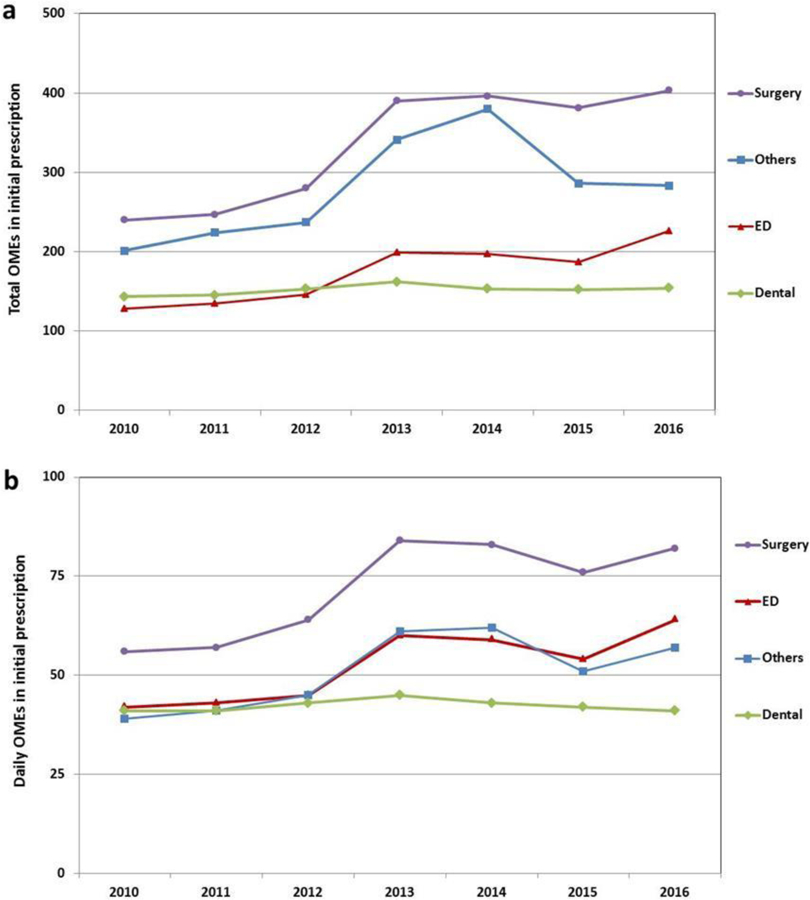

Opioid-naïve surgical patients were prescribed the highest total opioid amounts in all years studied (Figure 2a; Table 3 in the Supplemental Digital Content). Mean total OMEs per prescription for surgery increased from 240 mg (SD 509) in 2010 to 403 mg (SD 1369) in 2016. In addition, surgery patients received the highest number of daily OMEs in all years studied (Figure 2b; Table 4 in the Supplemental Digital Content); mean daily OMEs increased from 56 (SD 156) in 2010 to 82 (SD 273) in 2016. Total opioid amount per prescription among the “other” group reached a peak mean of 380 mg (SD 1179) in 2014, before falling to 283 mg (SD 1105) in 2016. In contrast, emergency medicine and dental prescription total opioid amounts exhibited flatter trajectories with lower OMEs. Dental patients received the lowest daily dosages of opioid throughout the study period.

Figure 2.

Surgical patients are prescribed the highest total (a) and daily (b) opioid amounts.

Days Supplied in Initial Opioid Prescriptions by Patient Group

Days of opioid supplied remained relatively constant across the study period, with patients in the “other” group receiving the most days (mean 6.4 [SD 7.0] in 2016), followed by surgery (5.4 [SD 3.4]), dental (3.8 [SD 2.8]), and emergency medicine (3.7 [SD 2.6]) (Table 5 in the Supplemental Digital Content).

Specific Opioid Prescribed in Initial Opioid Prescriptions

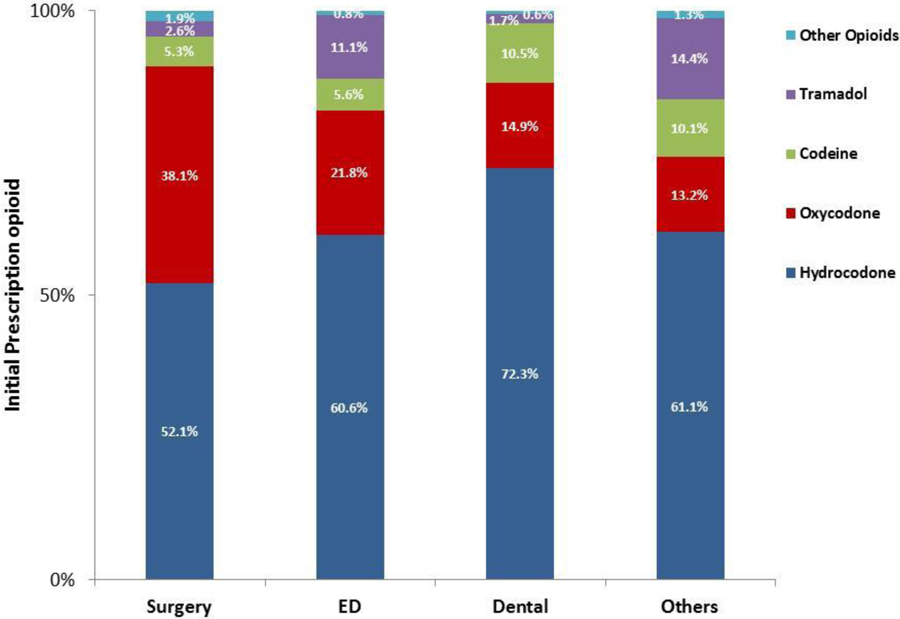

Potent opioids were most commonly prescribed by all provider types over the study period. (Figure 3; Table 6 in the Supplemental Digital Content). Surgery patients received the highest proportion of hydrocodone and oxycodone prescriptions (90.2%) and the highest share of oxycodone prescriptions (38.1%).

Figure 3.

Most initial prescriptions are for potent opioids (hydrocodone and oxycodone). Surgical patients are prescribed the highest proportion of potent opioids and the highest proportion of oxycodone.

DISCUSSION

The majority of existing recommendations around opioid prescribing focus on primary care indications, emphasizing the risks of prescribing opioids for conditions such as headache9 and acute low back pain.10,11 However, our findings illustrate the rising contribution of surgical, dental, and emergency medicine prescribing to opioid exposure among opioid-naïve patients, and underscore the need for greater attention to these important episodes of care. The percentage of new opioid prescriptions written to primary care and pain patients over the course of our study period decreased substantially, with a concomitant 15.8% increase in prescribing to surgical, emergency medicine, and dental patients.

The increase in prescribing share to these patients was most pronounced over the last two years examined: 2015 and 2016. It appears to be due to a relative increase in initial prescriptions written to surgical and dental patients and a relative decrease in initial prescribing by the primary care and pain physicians who most likely comprise the “other” group. One contributor to this change may be the dissemination of the Centers for Disease Control’s primary care guidelines for opioid prescribing, which were released in March 2016.11 These guidelines, along with the widespread attention paid to the opioid epidemic in both the scholarly and lay literature over the past several years, may have made primary care physicians more hesitant to prescribe opioids to opioid-naïve patients. Previously implemented state-level guidelines have been found to decrease opioid prescribing.12 Similarly, the attention paid to opioid prescribing by emergency physicians, which led to the promulgation of national guidelines in 2013,13 may be responsible for the relatively constant share of initial opioid prescriptions written to emergency medicine patients over our studied period. In contrast, until recently relatively little attention has been paid toward opioid prescribing to surgical and dental patients. Comprehensive guidelines on opioid prescribing to dental patients were not released until late 2017,14 while specific guidelines for postoperative surgical prescribing have been proposed but not yet accepted nationally.15, 16

Promoting judicious opioid prescribing has been identified as a key step in combatting the opioid epidemic.17 Our data suggest a need for increased focus on such prescribing to dental, emergency, and surgical patients, with the latter group requiring particular attention through education and guideline development. We observed that surgical patients were prescribed the highest initial amount of opioid. This aligns with prior studies demonstrating that postoperative opioid overprescribing by surgeons is common and occurs across nearly all case types.18 Potent opioids, which are responsible for more overdose deaths than weaker opioids,19 were prescribed most frequently to surgical patients, who also received the highest proportion of oxycodone prescriptions.

Our study has several limitations. Our data were originally collected for administrative purposes. Although we queried pharmacy claims, we only captured filled prescriptions; prescriptions provided but not filled and prescriptions paid for with cash were not included. Furthermore, our database did not permit linking filled prescriptions with provider information. In addition, we attributed specialty episodes of care based on billing codes, which may have inherent misclassification error. Finally, our data captures only employer-based insurance claims, and may not be representative of all patients, including the uninsured and underinsured.

CONCLUSIONS

The increase in initial opioid prescribing to surgical, emergency, and dental patients may relate to an increased focus on appropriate opioid prescribing by primary care and pain physicians. Our data emphasize the importance of developing guidelines, particularly for surgeons, who prescribe the highest dosages of opioid to opioid-naïve patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support

Grants include: R01DA042859 (Co-PIs Waljee, Brummett), AHRQ K08HS023313 (PI Waljee). Additional funding from the University of Michigan Medical School Dean’s Office, Michigan Genomics Initiative, and Precision Health Initiative. Dr. Waljee also receives research funding from the American College of Surgeons and the American Foundation for Surgery of the Hand, and serves as an unpaid consultant for 3M Health Information Systems. Drs. Brummett, Waljee and Englesbe receive funding from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, MDHHS or SAMHSA.

Dr. Brummett reports a patent for Peripheral Perineural Dexmedetomidine licensed to the University of Michigan, and is a consultant for Recro Pharma (Malvern, PA); not related to the present work. Dr. Brummett receives research funding from Neuros Medical Inc. (Willoughby Hills, Ohio). Dr. Brummett is a consultant for Recro Pharma and Heron Therapeutics.

References

- 1.Hedegaard H, Warner M, Minino AM. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2016. NCHS Data Brief 2017(294):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler MM, Ancona RM, Beauchamp GA, et al. Emergency Department Prescription Opioids as an Initial Exposure Preceding Addiction. Ann Emerg Med 2016; 68(2):202–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beauchamp GA, Winstanley EL, Ryan SA, et al. Moving beyond misuse and diversion: the urgent need to consider the role of iatrogenic addiction in the current opioid epidemic. Am J Public Health 2014; 104(11):2023–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, et al. Trends in Opioid Analgesic-Prescribing Rates by Specialty, U.S., 2007–2012. Am J Prev Med 2015; 49(3):409–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volkow ND, McLellan TA, Cotto JH, et al. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions in 2009. Jama 2011; 305(13):1299–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ringwalt C, Gugelmann H, Garrettson M, et al. Differential prescribing of opioid analgesics according to physician specialty for Medicaid patients with chronic noncancer pain diagnoses. Pain Res Manag 2014; 19(4):179–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lev R, Lee O, Petro S, et al. Who is prescribing controlled medications to patients who die of prescription drug abuse? Am J Emerg Med 2016; 34(1):30–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porucznik CA, Johnson EM, Rolfs RT, et al. Specialty of prescribers associated with prescription opioid fatalities in Utah, 2002–2010. Pain Med 2014; 15(1):73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langer-Gould AM, Anderson WE, Armstrong MJ, et al. The American Academy of Neurology’s top five choosing wisely recommendations. Neurology 2013; 81(11):1004–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deyo RA, Von Korff M, Duhrkoop D. Opioids for low back pain. Bmj 2015; 350:g6380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016; 65(1):1–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dowell D, Zhang K, Noonan RK, et al. Mandatory Provider Review And Pain Clinic Laws Reduce The Amounts Of Opioids Prescribed And Overdose Death Rates. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016; 35(10):1876–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Academy of Emergency Medicine. Emergency Department Opioid Prescribing Guidelines for the Treatment of Non-Cancer Related Pain. http://www.aaem.org/UserFiles/file/Emergency-Department-Opoid-Prescribing-Guidelines.pdf 2013; Accessed March 17, 2018.

- 14.Dr. Robert Bree Collaborative and Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group. Dental Guideline on Prescribing Opioids for Acute Pain Management. http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/20171026FINALDentalOpioidRecommendations_Web.pdf 2017; Accessed March 17, 2018.

- 15.Hill MV, Stucke RS, Billmeier SE, et al. Guideline for Discharge Opioid Prescriptions after Inpatient General Surgical Procedures. J Am Coll Surg 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.www.opioidprescribing.info. Accessed February 10, 2018.

- 17.Kolodny A, Frieden TR. Ten Steps the Federal Government Should Take Now to Reverse the Opioid Addiction Epidemic. JAMA 2017; 318(16):1537–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, et al. Wide Variation and Excessive Dosage of Opioid Prescriptions for Common General Surgical Procedures. Ann Surg 2017; 265(4):709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warner M, Trinidad JP, Bastian BA, et al. Drugs Most Frequently Involved in Drug Overdose Deaths: United States, 2010–2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2016; 65(10):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.