Abstract

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) represents a heterogeneous cluster of clinical phenotypes that are classically diagnosed by the time of adolescence. The possibility of late-life emergence of ASD has been poorly explored.

Methods

In order to more fully characterize the possibility of late-life emergence of behaviors characteristic of ASD in MCI and AD, we surveyed caregivers of 142 older persons with cognitive impairment from the University of Kentucky Alzheimer’s Disease Center Longitudinal Cohort using the Gilliam Autism Rating Scale-2.

Results

Participants with high autism index ratings (Autism ‘Possible/Very Likely’, n=23) reported significantly (statistically and clinically) younger age at onset of cognitive impairment than those who scored in the Autism ‘Unlikely’ range (n=119): 71.14±10.9 vs. 76.65±8.25 (p = 0.034). Additionally, those in Autism ‘Possible/Very Likely’ group demonstrated advanced severity of cognitive impairment, indicated by Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes scores.

Discussion

Data demonstrate that ASD behaviors may appear de novo of degenerative dementia and such behaviors are more prevalent in those with early onset dementia. Further work elucidating a connection between ASD and dementia could shed light on subclinical forms of ASD, identify areas of shared neuroanatomic involvement between ASD and dementias, and provide valuable insights that might hasten the development of therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: Autism, mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, behavior

Introduction

Behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia (BPSD) present significant issues in dementia care1. Many BPSD share similarities with those described in autism spectrum disorder (ASD)2, including anxiety, depression, executive functioning deficits, and communication deficits3. Diagnostic criteria for ASD are defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition to include, but are not limited to: deficits in social communication and social interaction; restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities including repetitive movements, use of objects, or speech; inflexibility in terms of routines, ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behavior; fixated interests; and hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input 4. The underlying etiology of ASD is not fully understood. Both ASD and dementia lead to behavioral disruptions associated with increased caregiver burden, use of antipsychotic medications, and increased direct care needs5,6.

Recognition of possible relationships between clinical features of ASD and dementia has sparked recent scientific investigation 7–9. Increased prevalence of dementia and younger age of onset have been observed in individuals with learning and developmental disabilities when compared to the typical population10,11. Yet, scientific literature significantly lacks representation of the aging experience for those with diagnosed ASD and high functioning individuals with undiagnosed ASD 12–14. Existing evidence has led to speculation that selective neuroanatomical involvement or shared mechanisms of disease might contribute to such overlapping behavioral sequela. Anatomical and behavioral similarities overlap in Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) and ASD, including frontal and temporal lobe cortical thickness and volume deficit, alterations in communication and impaired social abilities 5,13,15–17. Additionally, beta-amyloid precursor protein (βAPP) levels, a key protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), have been shown to be higher in blood plasma levels of children with severe autism and aggression than neurotypically-developing controls 18. Other studies have shown behavioral improvements in children with autism while using FDA-approved AD medications that modulate both acetylcholinergic and glutamatergic function, suggesting possible overlap in pharmacological responses in these distinct syndromes7,8.

The anatomical and behavioral relationship of autism and FTD, elevated βAPP levels, and the potential response of children with autism to AD medications raises the possibility of potential overlap among mechanisms of disease in autism and a variety of late-life, degenerative dementias. Additionally, behavioral expression of cognitive senescence associated with ASD warrants exploration. Little is known regarding aging and cognitive changes in those diagnosed with ASD or those who have ASD behavioral phenotypes without formal diagnosis13,19. The current study sought to explore the presence of ASD-type behaviors in participants with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia in a community-based cohort.

Methods

Participants

Participants in the current study were drawn from the University of Kentucky’s Alzheimer’s Disease Center (UK ADC) longitudinal cohort20. Participants consent to extensive annual cognitive and clinical examinations and enroll at any point in the cognitive continuum, but are preferentially enrolled while still cognitively normal. Full details of annual assessments and inclusion/exclusion criteria have been described elsewhere20. Each participant in the cohort has a study partner, who is usually a caregiver. ADC participants in the current study met inclusion criteria of diagnosis of MCI or dementia, a caregiver willing to participate, and a full clinical assessment within 24 months of current study participation (n=330). This study was approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board.

Diagnostic criteria

The diagnosis of MCI was determined according to the consensus guidelines developed by the Second International Working Group on MCI 21 and further adopted by the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup on Diagnostic Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease as follows: (1) a cognitive complaint by the subject or informant, or evidence for longitudinal decline on cognitive test performance (at least 1.5 standard deviation decline); (2) generally intact global cognition; (3) no or minimal functional impairment; (4) not demented according to DSM-IV criteria. The diagnosis of dementia was based on the criteria set forth by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) 4. Cause-specific dementia criteria include the Joint Working Group of the National Institute of the Neurologic and Communication Disorders and Stroke-AD and Related Disorders (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria for AD 22, NINDS-AIREN criteria for vascular dementia 23, AHA/ASA criteria for MCI due to cerebrovascular disease (VCI) consensus criteria for frontotemporal dementia24, and the 2005 Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) Consortium revised criteria 25.

Measures

Study partners and caregivers of UK ADC participants, including spouses/partners and adult children of participants, were asked to complete the Gilliam Autism Rating Scale-Second Edition (GARS-2)26. GARS-2 identifies frequency of ASD-type behaviors and is well established for screening and diagnosis of autism in pediatric and adolescent populations 26,27. The assessment is a reliable and valid measure with normative data for individuals aged 3–22 years 26,27. GARS-2 was chosen despite lack of validation for older adults because there is not a validated observation-based tool assessing autism-type behaviors for those in late life. The tool is used in this study as means for exploration and identification of behaviors characteristic of autism in a sample of older adults with cognitive impairment, not for diagnostic purposes. Other assessments used for screening autism were evaluated but deemed inappropriate for this study. The Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) was not selected because it is most often administered directly to the person via interviewing without caregiver involvement 28,29. Our sample is known to have cognitive impairment and possible communication deficits as a result and is not well-suited for the AQ assessment. Additionally, the Social Responsiveness Scale, another assessment often used to diagnose ASD, was not selected due to its limited scope of behavioral assessment. This study sought to explore a breadth of behaviors characteristic of autism as observed in our older adult cohort.

To complete the GARS-2, caregivers ranked 42 objective statements of characteristic ASD behaviors based on observable frequency. Each item was ranked on an ordinal scale from 0–3 (0 indicates the behavior is never observed, 1 is seldom observed, 2 is sometimes observed, and 3 is frequently observed). The assessment is grouped into three subscales: behaviors, communication, and social interaction. Standard scores of the subscales were combined and used to determine the Autism Index Score (AIS) 26. AIS were categorized according to GARS-2 guidelines as follows: ‘Autism Possible/Very Likely’ (AIS ≥ 70) and ‘Autism Unlikely’ (AIS < 70). We note that to date there is no evidence establishing normative data for characteristics of ASD in the geriatric population. Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) 30, Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDRSUM) 31,32, and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) 33 were used to characterize severity of global cognitive impairment and assess comorbid depression 34.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical features of ADC participants classified as Autism Possible/Very Likely and Autism Unlikely based on caregiver responses to the GARS-2 were compared using t-test or chi-square tests. Participant characteristics associated with AIS were further evaluated using logistic regression, where the outcome of interest was group membership (Autism Possible/Very Likely vs. Unlikely), and linear regression, where the outcome of interest was the AIS. Backward selection was used to identify the most parsimonious model, using stepAIC() function of the MASS package in R 33. To further assess the relationship between ASD-type behaviors and cognitive impairment, AIS was compared between CDR global score (i.e., 0, 0.5, 1, 2, or 3) and diagnosis (i.e., MCI vs. dementia) using two-way ANCOVA and Tukey’s HSD pairwise comparisons to compare CDR global scores35. Age, sex, and education were included as covariates. Statistical significance was set at 0.05, and all statistical analyses were performed using the R 3.5.1 console34.

Results

One-hundred and forty-eight questionnaires were returned. Data from six respondents were excluded because the participants’ most recent clinical assessment was more than two calendar years from the time of GARS completion, leaving 142 surveys for analysis. There were no significant differences between the UK ADC participants whose caregivers did or did not respond to the survey in basic demographics or clinical status (age, gender, education, CDR sum of boxes, or dementia diagnosis). Aside from trend differences in age, the six excluded ADC participants did not differ from included participants on basic demographics or clinical status. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. None of the participants were known to have a diagnosis of autism or ASD prior to survey completion.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| All Participants | ASD Unlikely | ASD Possible/Likely | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Variablesa | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | p |

| Age at GARS | 79.84 | 8.39 | 80.41 | 8.00 | 76.96 | 9.87 | 0.126 |

| Age of Onset | 75.67 | 8.98 | 76.65 | 8.25 | 71.14 | 10.90 | 0.034 |

| Years of Education | 16.35 | 3.43 | 16.28 | 3.33 | 16.70 | 3.97 | 0.641 |

| MMSE | 22.00 | 7.39 | 22.95 | 6.33 | 16.50 | 10.41 | 0.014 |

| GDS | 2.26 | 2.24 | 2.13 | 2.14 | 2.54 | 1.27 | 0.330 |

| CDR sum of boxes | 5.08 | 5.05 | 4.23 | 4.28 | 9.50 | 6.38 | 0.001 |

| Years Since Diagnosis | 4.44 | 3.62 | 4.17 | 3.24 | 5.73 | 4.90 | 0.166 |

| Years Between Visit & GARS | 0.42 | 0.63 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.79 | 0.501 |

| Discrete Variablesb | n | % | n | % | n | % | p |

| Female | 67 | 0.47 | 56 | 0.47 | 11 | 0.48 | 0.946 |

| Caucasian | 133 | 0.94 | 112 | 0.94 | 21 | 0.91 | 0.612 |

| ≥1 Copy of ApoE4c | 35 | 0.27 | 28 | 0.26 | 7 | 0.37 | 0.314 |

| MCI Diagnosis | 48 | 0.34 | 46 | 0.39 | 2 | 0.09 | 0.005 |

| Dementia Diagnosis | 94 | 0.66 | 73 | 0.61 | 21 | 0.91 | 0.005 |

Note: GARS = Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (2nd Edition); ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder; MMSE = Mini-Mental Status Exam; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; CDR = Clinical Dementia Rating; MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment.

T-tests between ASD Unlikely and ASD Possible/Likely groups.

χ2-tests between Unlikely and Possible/Likely groups.

ApoE data available for only 128 participants; 109 in ASD Unlikely and 19 in ASD Possible/Likely.

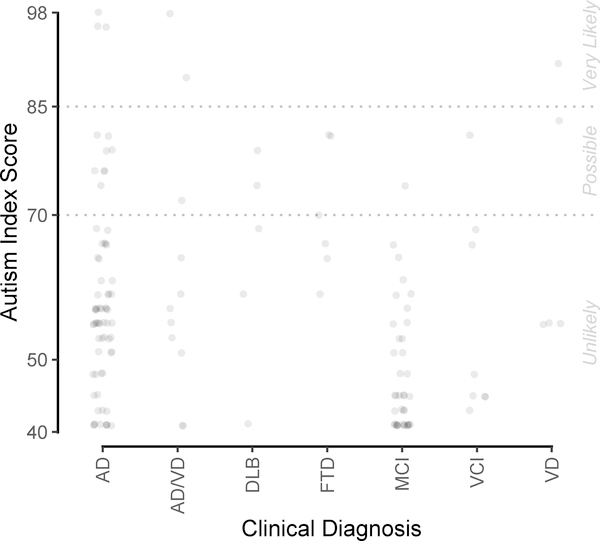

As shown in Figure 1, 60.9% (14 of 23) of the respondents in the Autism Possible/Very Likely group were diagnosed as having dementia due to AD, including three with mixed AD and vascular dementia (VD). The remaining participants in the Autism Possible/Very Likely with non-AD dementias include FTD (n = 3), DLB (n = 2), and VD (n = 2). One participant diagnosed as having MCI and one diagnosed as having VCI also scored in the ‘Possible/Very Likely’ range, suggesting the presence of behaviors characteristic of ASD with milder forms of cognitive impairment, which has not been previously described.

Figure 1. GARS-2 AIS by Clinical Diagnosis.

Note: AISs for 142 participants, by clinical diagnosis most temporally proximal to completion of GARS-2. Jittering used to avoid overplotting. AIS = Autism Index Scores; DAT = Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type; DLB = Dementia with Lewy Bodies; FTD = Frontotemporal Dementia; MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment; VCI = Vascular Cognitive Impairment; VD = Vascular Dementia.

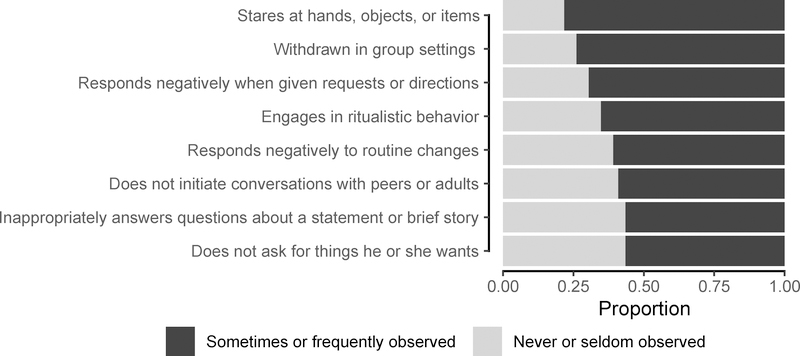

Between-group comparisons of the Autism Unlikely and Autism Possible/Likely groups demonstrated associations of high AIS scores with younger age of onset of cognitive impairment and increased severity of impairment (Table 1). This result tended to persist when the respondents were restricted to just those whose study partner was a person with dementia (Possible/Very Likely, n=21 and Unlikely, n=74): 71.8±8.8 vs. 76.1±10.7 (p = 0.10). ADC participants rated in the Possible/Very Likely range were also younger at the time of the GARS-2 survey and more likely to have a dementia diagnosis relative to the Unlikely group (Table 1). As expected, participants in the Autism Possible/Very Likely group had significantly higher subscale scores in all three domains: social interaction, communication, and stereotyped behaviors (Table 2). Scores on the behavior subscales (behavior, communication, social interaction) were lowest overall in both groups (Table 2). Collected from the GARS-2, the most frequently observed ASD-type behaviors are shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Between Group Comparisons of GARS-2 AIS and Subscales

| All Participants |

ASD Unlikely |

ASD Possible/Likely |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| AIS | 56.58 | 14.05 | 51.68 | 8.51 | 81.96 | 8.56 |

| Behavior | 2.76 | 1.77 | 2.24 | 1.31 | 5.48 | 1.31 |

| Communication | 3.62 | 2.73 | 2.71 | 1.72 | 8.30 | 2.10 |

| Social Interaction | 3.54 | 2.51 | 2.72 | 1.55 | 7.78 | 2.26 |

Note: AIS = Autism Index Score; ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder. For group comparisons, all ps < 0.001

Figure 2. Prevalent Behaviors in ASD Possible/Very Likely Group.

Note: Select ASD-type behaviors most prevalent in the ASD Possible/Very Likely group. ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder.

In the full multiple logistic regression model, where autism being Possible/Very Likely vs Unlikely was the dependent variable, only CDRSUM (OR for 1-point increase in CDRSUM = 1.17, 95% CI [1.00, 1.38], p = 0.055) approached significance at the 0.05 level. In the reduced model, CDRSUM (OR = 1.17, 95% CI [1.07, 1.28], p < 0.001) and age at onset of cognitive impairment were retained (OR = 0.95, 95% CI [0.90, 1.01], p = 0.09), though age at onset only trended toward significant. In the full linear regression model with AIS as the dependent variable, CDR sum of boxes was the only significant predictor (for a 1-point reduction in CDR, β=1.51, SE(β)=0.35, 95% CI [0.81, 2.20], p<0.0001). In the reduced model, CDR sum of boxes (β=1.51, SE(β)=0.30, 95% CI [0.92, 2.10], p<0.0001) and age (β=−0.27, SE(β)=0.14, 95% CI [−0.54, −0.01], p = 0.05) were retained.

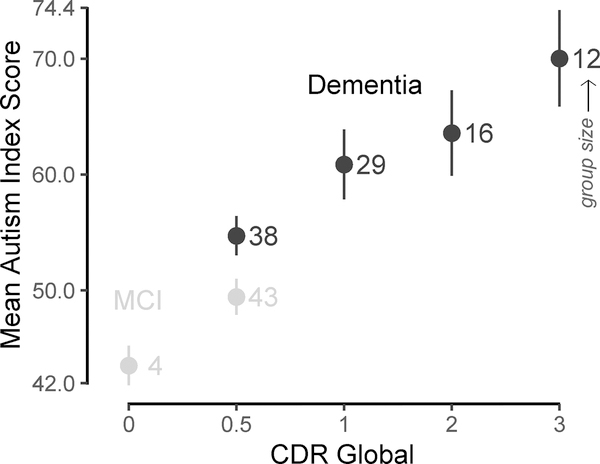

As is evident in Figure 3, there were significant main effects of CDR global, F(4, 132) = 9.085, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.21, 95% CI [0.11, 0.35], and age, F(1, 132) = 3.915, p = 0.05, η2 = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.02, 0.08]. There was a trend effect of diagnosis, F(1, 132) = 3.584, p = 0.06, η2 = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.06] and no effect of sex or education, ps > 0.68. Pairwise comparisons showed that AIS was significantly higher on CDR global scores of 1, 2, and 3 compared to CDR 0.5, ps < 0.02. CDR 3 was also significantly higher than CDR 0, p = 0.02. All other comparisons were nonsignificant, ps > 0.11. Post hoc results were similar when excluding the four participants with CDR 0.

Figure 3. Mean GARS-2 AIS by Severity of Impairment.

Note: Mean AIS (with SE bars) by CDR Global score and diagnosis. Numerals in the plot correspond to group size, e.g., 12 participants were demented with CDR 3. Grey dotted line indicates cut-off for possible ASD. AIS = Autism Index Score; CDR = Clinical Dementia Rating; MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment.

Discussion

In this study, we found that ASD-type behaviors are commonly reported by caregivers of community-dwelling persons with cognitive impairment and dementia. Based on AIS scores, 16.2% of participants would be classified as Autism Possible/Very Likely. Dementia due to AD was the primary or contributing diagnosis for 61% of participants with behaviors characteristic of ASD (i.e., Autism Possible/Very Likely). Participants with other types of dementia (FTD, DLB, VD) were also identified as having ASD-like behavior. While previous research identified increased behavioral characteristics of ASD in individuals with FTD 5,15,16,36; prior reports have not explored a possible relationship with other dementias, such as AD. Additionally, characteristics of ASD were reported for some participants who carried diagnoses of MCI. These findings suggests that behaviors characteristic of ASD may emerge as a result of neurodegenerative processes because the frequency of ASD-like behaviors increased with advancing severity of cognitive impairment.

Age of onset of cognitive symptoms was significantly earlier in the Autism Likely group than those in the Autism Unlikely group. It is possible that lifelong subclinical ASD may manifest only when neurological function is compromised by the development of even the mildest of cognitive pathologic insults in older adulthood9,13,16. Pathological overlap in neuroanatomical structures and systems in ASD and dementia may create earlier behavioral burden in the presence of degenerative disease, as evidenced by age of onset of cognitive impairment and presence of behavioral symptoms6,37,38. Underlying ASD, along with learning and developmental disabilities may lower the threshold for onset of AD, consistent with increased prevalence of dementia in those with these conditions10,11. Given our limited sample size, these results should be interpreted cautiously.

Consistent with the extant literature, younger age was also associated with increased cognitive impairment severity39. Savva and colleagues40 found similar patterns of heightened impairment at younger ages when looking at neuropathological onset of Alzheimer’s disease, cerebral atrophy, and cerebrovascular disease. Neurochemical abnormalities have also been identified to be most widespread and severe in patients with dementia in their 7th and 8th decade of life compared to later ages 37. The current study revealed that increased severity of impairment is related to increased likelihood of ASD-like behaviors. Widespread and global cortical involvement in both ASD and neurodegenerative disease may produce similar behavioral features that are responsible for the identification of characteristics of ASD in our cohort 2,19,37,41.

The GARS-2 uses three subscales (behavior, communication, and social interaction) to determine the AIS. Interestingly, this study demonstrated high involvement of all three subscales in those with dementia who engage in behaviors associated with ASD. High involvement of all subscales may be indicative of widespread, overlapping neuroanatomical involvement in both conditions41. Behavior, communication, and social interaction may also share overlapping neurocognitive networks which become unmasked by these conditions.

Several limitations inherent in the current study deserve comment. First, the use of a retrospective cross-sectional design can show association, but causality cannot be inferred. Limitations also include response and retrospective reporting biases given the nature of the GARS-2. We note that the survey instrument, while validated in childhood autism has not been validated in older adults. In addition, the response rate of 58% may indicate self-selection bias among the respondents. Finally, we note that the study participants were predominately European American, with high educational attainment living in one geographical region, limiting generalizability of the study findings.

Despite these weaknesses, there are several strengths of this study. It is, to our knowledge, the first investigation of similarities among behaviors characteristic of ASD (behavior, communication, and social interaction) and late-life neurodegenerative disease including AD in a cohort without diagnosed ASD. Utilization of caregiver reporting and symptom assessment has been established as an effective and reliable tool for symptom reporting in dementia care42. Despite the lack of a validated measure to assess behaviors characteristic of ASD in late-life dementia, our use of a widely-used and valid tool (GARS-2) specific to autism, strengthens the present findings.

These data demonstrate that late-life degenerative dementias and ASD share common behavioral symptoms across dementia etiologies and across the cognitive continuum in some individuals. Again, while causality cannot be inferred from these findings, it is intriguing to hypothesize that shared neuroanatomical substrates and pathological underpinnings are responsible for the associations seen in this study. Given the significant morbidity and caregiver burden associated with behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia, an enhanced understanding of such behavioral expression may aid in the identification of effective interventions for late-life degenerative dementias. The emergence of behaviors typically associated with ASD in degenerative cognitive impairment deserves further study as science moves forward in seeking an integrated understanding of the behavioral sequelae of neurologic dysfunction across the lifespan.

Acknowledgements

This study utilized University of Kentucky Alzheimer’s Disease Cohort participants. Funding for the longitudinal cohort is provided by NIH/NIA P30 AG028383. We are grateful to our participants and their caregivers.

Funding: This study was supported by NIH/NIA 1 P30 AG028383.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Ecerejeira J, Lagarto L, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB. Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. Frontiers in Neurology. 2012;3:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SH, Lord C. Chapter 1.2 - The Behavioral Manifestations of Autism Spectrum Disorders A2 - Buxbaum, Joseph D In: Hof PR, ed. The Neuroscience of Autism Spectrum Disorders. San Diego: Academic Press; 2013:25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace GL, Kenworthy L, Pugliese CE, et al. Real-World Executive Functions in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Profiles of Impairment and Associations with Adaptive Functioning and Co-morbid Anxiety and Depression. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(3):1071–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-4. 1994.

- 5.Baez S, Ibanez A. The effects of context processing on social cognition impairments in adults with Asperger’s syndrome. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2014;8:270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hornberger M, Piguet O, Kipps C, Hodges JR. Executive function in progressive and nonprogressive behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2008;71(19):1481–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossignol DA, Frye RE. The use of medications approved for Alzheimer’s disease in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeidan-Chulia F, de Oliveira BH, Salmina AB, et al. Altered expression of Alzheimer’s disease-related genes in the cerebellum of autistic patients: a model for disrupted brain connectome and therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caselli RJ, Langlais BT, Dueck AC, Locke DEC, Woodruff BK. Subjective Cognitive Impairment and the Broad Autism Phenotype. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2018;32(4):284–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper SA. High prevalence of dementia among people with learning disabilities not attributable to Down’s syndrome. Psychological medicine. 1997;27(3):609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayen E, Possin KL, Chen Y, Cleret de Langavant L, Yaffe K. Prevalence of Aging, Dementia, and Multimorbidity in Older Adults With Down SyndromeAging, Dementia, and Multimorbidity in Older Adults With Down SyndromeAging, Dementia, and Multimorbidity in Older Adults With Down Syndrome. JAMA Neurology. 2018;75(11):1399–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James IA, Mukaetova-Ladinska E, Reichelt FK, Briel R, Scully A. Diagnosing Aspergers syndrome in the elderly: a series of case presentations. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2006;21(10):951–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geurts HM, Vissers ME. Elderly with Autism: Executive Functions and Memory. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(5):665–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Happe F, Charlton RA. Aging in autism spectrum disorders: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2012;58(1):70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendez MF, Shapira JS, Miller BL. Stereotypical movements and frontotemporal dementia. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2005;20(6):742–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Midorikawa A, Kawamura M. The Relationship between Subclinical Asperger’s Syndrome and Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders extra. 2012;2:180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raznahan A, Toro R, Daly E, et al. Cortical anatomy in autism spectrum disorder: an in vivo MRI study on the effect of age. Cerebral cortex (New York, NY : 1991). 2010;20(6):1332–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sokol DK, Chen D, Farlow MR, et al. High levels of Alzheimer beta-amyloid precursor protein (APP) in children with severely autistic behavior and aggression. Journal of child neurology. 2006;21(6):444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell PS, Klinger LG, Klinger MR. Patterns of Age-Related Cognitive Differences in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(10):3204–3219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitt FA, Nelson PT, Abner E, et al. University of Kentucky Sanders-Brown healthy brain aging volunteers: donor characteristics, procedures and neuropathology. Current Alzheimer research. 2012;9(6):724–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment - Beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. Vol 2562004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roman GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology. 1993;43(2):250–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilliam JW. GARS-2: Gilliam Autism Rating Scale–Second Edition.. Austin, TX: PRO-ED; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montgomery J, Newton B, Smith CD. Test reviews: Gilliam, J. (2006). GARS-2: Gilliam Autism Rating Scale-Second Edition. Austin, TX: PRO-ED.. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2008;26(4):395–401. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, Clubley E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger Syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians (vol 31, pg 5, 2001). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2001;31:603–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodbury-Smith MR, Robinson J, Wheelwright S, Baron-Cohen S. Screening adults for Asperger Syndrome using the AQ: a preliminary study of its diagnostic validity in clinical practice. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005;35(3):331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of psychiatric research. 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 1982;140:566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. Journal of psychiatric research. 1983;17(1):37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perneczky R, Wagenpfeil S, Komossa K, Grimmer T, Diehl J, Kurz A. Mapping scores onto stages: mini-mental state examination and clinical dementia rating. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(2):139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lüdecke D Sjstats: statistical functions for regression models. R package version 0.14. 0. In:2018.

- 36.Geurts HM, Vissers ME. Elderly with autism: executive functions and memory. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(5):665–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossor Iversen LL, Reynolds GP Mountjoy CQ, Roth M. Neurochemical characteristics of early and late onset types of Alzheimer's disease. British Medical Journal (Clinical research ed). 1984;288(6422):961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreau N, Rauzy S, Viallet F, Champagne-Lavau M. Theory of mind in Alzheimer disease: Evidence of authentic impairment during social interaction. Neuropsychology. 2016;30(3):312–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rossor M, Fox NC, Mummery CJ, Schott JM, Warren JD. The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. Lancet neurology. 2010;9(8):793–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Savva GM, Wharton SB, Ince PG, Forster G, Matthews FE, Brayne C. Age, neuropathology, and dementia. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360(22):2302–2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Courchesne E, Redcay E, Morgan JT, Kennedy DP. Autism at the beginning: microstructural and growth abnormalities underlying the cognitive and behavioral phenotype of autism. Development and psychopathology. 2005;17(3):577–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jicha GA. Medical management of frontotemporal dementias: the importance of the caregiver in symptom assessment and guidance of treatment strategies. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;45(3):713–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]