Abstract

#Fitspiration is a popular social media trend for sharing fitness-related content. To date, however, it is not clear how best to harness the power of this trend to improve users’ health, including how best to tailor its content. In this study, a cross-sectional survey assessed intentions and perceptions of users who host fitspiration accounts on Instagram (n = 65), as well as young adult followers (n = 270). Fitstagrammers and men (across user groups) preferred messaging about earning fitness, whereas followers and women (across user groups) preferred messaging about the benefits of exercise efforts. Both fitstagrammers and followers also noted that they experience both positive and negative feelings in response to fitspiration images, with followers and women reporting more frequent negative feelings (vs. followers and men, respectively). These findings can inform the use of fitspiration as a health promotion tool, particularly with respect to tailoring content to match user preferences.

Keywords: social media, physical activity, social comparison, young adults, body image, gender, communication, health behaviour, health promotion

Instagram is one of the most frequently used social media platforms among young adults (Pew Research Center, 2018); this site allows users to share pictures and videos with other users, and to post to and search for themes using hashtags (#). A popular trend on Instagram is interacting with fitness-related content, both as a leisure activity and a source for health and fitness information, using the hashtag #fitspiration (Jong and Drummond, 2016; Tiggemann and Zaccardo, 2015). A general assumption about this trend is that fitspiration posts are intended to inspire viewers to adopt and engage in healthy behaviours (Boepple et al., 2016). However, concerns regarding followers’ exposure to idealized physical figures have surfaced, raising questions about the influence of fitspiration posts on health outcomes (e.g., body satisfaction and self-esteem; Tiggemann and Zaccardo, 2015; Fardouly et al., 2018).

For example, hashtags such as #thinspiration and #bonespiration promote engagement in extreme measures to meet an excessively thin body image ideal (Ghaznavi and Taylor, 2015), and these hashtags have been banned by Instagram (Judkis, 2012). Content analysis has demonstrated that images tagged as thinspiration and bonespiration show “thin and objectified” bodies more so than those tagged as fitspiration, which show more muscular and fit bodies (Talbot et al., 2017). Yet similar work has noted that the frequencies of dieting and fat-shaming messages do not differ between thinspiration and fitspiration posts (Boepple and Thompson, 2016). Similar to the effects of thinspiration or bonespiration, experimental exposure to fitspiration images results in decreased body satisfaction and increased negative mood (e.g., Robinson et al., 2017; Slater, Varsani, and Diedrichs, 2017; Tiggemann and Zaccardo, 2015). Thus, although fitspiration may be an improvement over previous inspirational trends, those who both post and follow fitspiration messages may still absorb negative messages, which may promote unhealthy self-concepts and/or health behaviours.

The presence or strength of these effects often depend on individual differences (e.g., pre-existing self-objectification; Prichard et al., 2017), however, and participants in these studies typically are women who are not selected for their interest in or typical behavior regarding fitspiration posts. As such, it is not clear whether these responses (or user preferences, etc.) generalize to young adults – particularly young men – who elect to post or follow fitspiration. Little is known about the intentions or perceptions of either users who host fitspiration (only) accounts or young adult users who regularly follow such accounts, with emphasis on describing any existing gender differences. Additional information in these areas would be useful for informing health messaging or health interventions to target (potentially) vulnerable Instagram users. Toward these ends, the present study was designed as a cross-sectional survey to capture the perceptions of both users who post fitspiration content (i.e., fitstagrammers) and young adult users who follow fitspiration accounts (i.e., followers).

Methods

Recruitment and Participants

Fitstagrammers.

Instagram users who had recently posted an image with the #fitspiration tag were considered for participations. These users were eligible if they were at least 18 years old and had 300 or more followers for an account with a majority of posts that were related to fitness or health. Users who met these criteria were contacted via direct message on Instagram explaining the study and directing them to click on the survey link to participate. The sample of fitstagrammers (n = 65, MAge = 30.2 years) comprised 71% women. The majority (59%) identified the U.S. as their home country, with other countries including the U.K. (9%), other European countries (e.g., Germany; 9%), Australia (5%), Canada (5%), India (5%), South Africa (2%), Egypt (2%), the Dominican Republic (2%), and Peru (2%).

Followers.

Young adult fitspiration followers were recruited via electronic posts on fitstagrammers’s pages, Twitter, and a public message board at the supporting institution. Respondents were eligible if they were 18–23 years old and self-identified as voluntarily following fitspiration accounts on Instagram. The sample of followers (n = 270, MAge = 20.1 years) comprised 78% women; all but one respondent identified the U.S. as their home country (99%).

Measures

Fitspiration use.

A set of items referred to the frequency and type of fitspiration images posted/viewed. Fitstagrammers were asked to indicate how often they post fitspiration images (less than once a month, monthly, weekly, 2–6 times a week, daily, or multiple times a day), and followers were asked how often they view fitspiration images (less than daily, 1–5 times daily, 5–9 times a day, or more than 10 times a day). Fitstagrammers were also asked to indicate the type(s) of images they post: pictures of myself in regular clothes, pictures of myself in workout clothes, pictures of myself in the gym, pictures of my meals, pictures of my workout plan, pictures with quotes, pictures with sponsored items, videos of my workouts, and videos of preparing meals). Followers were asked to indicate how often they engage in exercise (1–2 times a week, 3–4 times a week, 5–6 times a week, > 6 times a week)

Reasons for posting or following fitspiration.

Based on the top reasons for sharing information about physical activity over social networking sites identified by Pinkerton et al. (2016), participants were asked to indicate the reasons they follow fitspiration accounts or post fitspiration content. Options were: to show people what I am up to/to see what others are up to, to inspire others/to receive inspiration, to gain recognition for what I am doing, to invite others to share, just for fun, to motivate myself and keep myself accountable, to receive feedback from others in the community, to learn tips and exercises I can use and other.

Typical response to viewing fitspiration.

Participants were asked to indicate their typical emotional reactions to viewing fitspiration content. The prompt stated “Sometimes when people see fitspiration images they feel positive (e.g. inspired, excited, confident), while other times they may feel negative (e.g. angry, frustrated, ashamed). We would like to know how often you experience these reactions. When I view fitspiration posts I feel:” Response were rated on a 5-point scale, from negative all of the time (1) to positive all of the time (5).

Image preference.

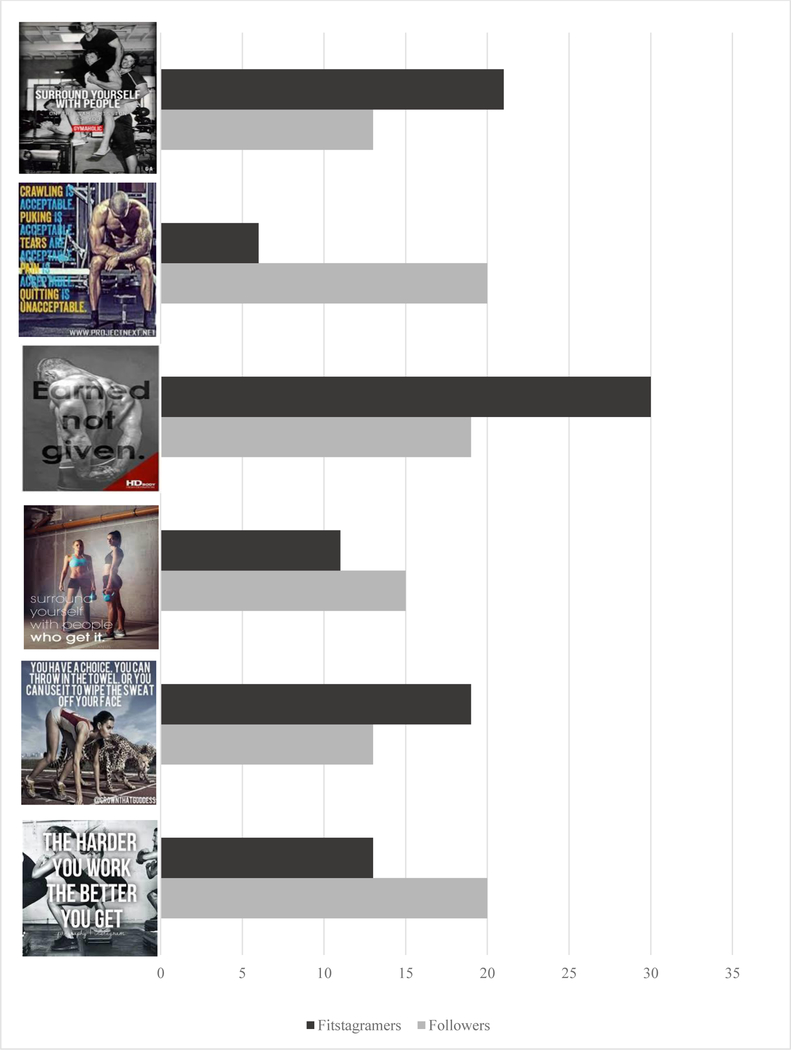

Images were selected from a Google image search of the fitspiration themes identified by Deighton-Smith and Bell (2017). Images conveyed messages through text that was overlaid on images of both men and women engaging in physical activity. Participants were asked to indicate which of the images they found most motivating for physical activity (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Fitspiration image/caption preferences by participant type (fitstagramers vs. followers; percent of subsample).

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the supporting institution. Through electronic messages and advertisements described above, interested individuals were directed to a web-based survey, where they provided electronic informed consent. Surveys for both participant groups were very similar, as described above, but were tailored to address the perceptions and experiences of their respective group (i.e., fitstagrammer vs. follower). Student participants at the supporting institution were able to earn course credit as compensation; those who were not enrolled in a relevant course, or were not students (fitstagrammers), were offered the opportunity to enter a lottery to win a $25 Amazon gift card.

Data Analysis

As an initial examination of fitspiration perceptions among fitstagrammers and followers, we first present descriptive data, in order to characterize these groups. Exploratory examination of differences between the responses of fitstagrammers and followers use Chi-square tests (for categorical variables, where appropriate) and independent samples t-tests (for continuous variables). The same approach was used to test for differences between the responses of women and men.

Results

Frequency of Exercise and Fitspiration Engagement

As noted, we were interested in what proportion of our samples identified as men. Across the all participants, 20% identified as men; men comprised 27% of fitstagrammers and 15% of fitspiration followers. In the entire sample, the largest subsets of fitstagrammers indicated that they had operated a fitspiration account for 1–2 years (40%) and that they post to it daily (33%). However, responses to both of these items showed meaningful ranges (see Table 1), with some fitstagrammers indicating that they had operated an account for 0–5 years and that they post monthly to multiple times per day. The majority of followers reported viewing fitspiration accounts 1–5 times daily (51%), with subsets endorsing less than daily to more than 10 times a day (see Table 2). There were no significant gender differences in these frequencies (ps > 0.10). Followers reported engaging in exercise frequently (see Table 2), and the frequency of viewing fitspiration accounts was positively associated with exercise frequency among followers (r = 0.19, p = 0.02).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for reported engagement with fitspiration among fitstagramers (n = 65, women = 57, men = 21).

| Length of Time Operating an Account |

All (n, %) | Women (n, %) | Men (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 year | 12 (18%) | 9 (16%) | 3 (14%) |

| 1–2 years | 26 (40%) | 19 (33%) | 7 (33%) |

| 3–5 years | 17 (26%) | 11 (19%) | 6 (29%) |

| More than 5 years | 3 (5%) | 3 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Frequency of Posts | All (n, %) | Women (n, %) | Men (n, %) |

| Less than 1 per month | 2 (3%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Monthly | 3 (5%) | 2 (5%) | 1 (6%) |

| Weekly | 6 (10%) | 3 (7%) | 3 (19%) |

| 2–6 times per week | 18 (32%) | 13 (31%) | 5 (31%) |

| Daily | 19 (33%) | 12 (28%) | 7 (44%) |

| Multiple times per day | 10 (17%) | 10 (24%) | 0 (0%) |

| Reasons for Posting | All (n, %) | Women (n, %) | Men (n, %) |

| To show people what I am up to | 31 (48%) | 25 (44%) | 6 (29%) |

| To inspire others | 50 (77%) | 37 (65%) | 13 (62%) |

| To gain recognition for what I am doing | 17 (26%) | 14 (24%) | 3 (14%) |

| To invite others to share | 15 (23%) | 11 (19%) | 4 (19%) |

| Just for fun | 29 (45%) | 25 (44%) | 4 (19%) |

| To motivate myself and keep myself accountable | 45 (69%) | 35 (61%) | 10 (48%) |

| To get tips and feedback from others | 19 (29%) | 15 (26%) | 4 (19%) |

| Typical Response to Fitspiration Posts |

All (n, %) | Women (n, %) | Men (n, %) |

| Negative all of the time | 22 (39%) | 14 (33%) | 8 (57%) |

| Negative most of the time | 30 (54%) | 24 (57%) | 6 (43%) |

| Equally positive and negative | 4 (7%) | 4 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Positive most of the time | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Positive all of the time | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for reported engagement with fitspiration among followers (n = 270, women = 212, men = 61).

| Length of Time Following | All (n, %) | Women (n, %) | Men (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 year | 82 (30%) | 60 (28%) | 22 (36%) |

| 1–2 years | 146 (54%) | 115 (54%) | 31 (51%) |

| 3–5 years | 30 (11%) | 25 (12%) | 5 (8%) |

| More than 5 years | 8 (3%) | 7 (3%) | 1 (2%) |

| Frequency of Viewing | All (n, %) | Women (n, %) | Men (n, %) |

| Less than daily | 100 (38%) | 78 (38%) | 52 (37%) |

| Less than 5 times per day | 137 (51%) | 101 (49%) | 36 (61%) |

| 5–9 times per day | 24 (9%) | 24 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

| More than 10 times per day | 5 (2%) | 4 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Reasons for Following | All (n, %) | Women (n, %) | Men (n, %) |

| To see what people are up to | 62 (23%) | 47 (22%) | 15 (25%) |

| To get inspired/for motivation | 199 (74%) | 170 (80%) | 29 (48%) |

| To learn tips and exercises I can use | 220 (81%) | 178 (84%) | 42 (69%) |

| Just for fun | 85 (31%) | 63 (30%) | 22 (36%) |

| Exercise Frequency | All (n, %) | Women (n, %) | Men (n, %) |

| 1–2 times/week | 63 (23%) | 49 (23%) | 14 (23%) |

| 3–4 times/week | 102 (38%) | 88 (42%) | 14 (23%) |

| 5–6 times/week | 85 (31%) | 59 (28%) | 26 (43%) |

| More than 6 times/week | 16 (6%) | 11 (5%) | 5 (8%) |

| Typical Response to Fitspiration Posts |

All (n, %) | Women (n, %) | Men (n, %) |

| Negative all of the time | 36 (14%) | 18 (9%) | 18 (32%) |

| Negative most of the time | 148 (56%) | 121 (59%) | 27 (47%) |

| Equally positive and negative | 63 (24%) | 51 (25%) | 12 (21%) |

| Positive most of the time | 13 (5%) | 13 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Positive all of the time | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

Reasons for Posting or Following Fitspiration

As shown in Table 1, the most common reasons for posting fitspiration among fitstagrammers were to inspire others (77%) and to keep themselves motivated and accountable (69%). Followers reported the most common reasons for following fitspiration as to learn exercises and tips that they could use for themselves (81%) and to be inspired to exercise (74%; see Table 2). A noteworthy discrepancy between fitstagrammers and followers appeared for the reason “to show people what I am up to (fitstagrammers)/to see what others are up to (followers).” A greater proportion of fitstagrammers selected this reason, relative to followers (χ2 = 7.90, p = 0.005). This discrepancy did not differ by gender (χ2 = 0.83, p = 0.47).

Common Reactions to Fitspiration

Of the options presented, the largest subsets of fitstagrammers reported feeling negative at least sometimes (50%) when viewing fitspiration images, followed by feeling mostly positive (42%). Followers reported feeling negative at least sometimes (64%) and feeling mostly positive (11%) when viewing fitspiration posts. Followers were more likely than fitstagrammers to feel negative after viewing fitspiration posts (t[116.56] = 5.40, p < 0.0001), and women were more likely than men to feel negative after viewing posts (t[66.48] = 4.65, p < 0.0001). Gender did not moderate the effect of respondent type (fitstagrammer vs. follower) on ratings of common reactions to posts, however (F[1, 212] = 0.62, p = 0.43).

Fitspiration Image Preference

The largest subsets of fitstagrammers (30%) selected an image with the underlying message of “fitness is earned and not given” as the one they found most inspiring (#3 in Figure 1). However, followers selected posts that emphasized not quitting and the benefits of effort (20% in both cases; #2 and #6 in Figure 1). This difference between respondent type was statistically significant (χ2 = 10.02, p = 0.04). Although men were most likely to prefer a post with the message “fitness is earned and not given” (#4 in Figure 1), whereas women were most likely to prefer a post that emphasized the benefits of effort (#1 in Figure 1; χ2 = 18.96, p = 0.002), gender did not moderate the effect of respondent type (fitstagrammer vs. follower; ps > 0.21).

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that fitstagrammers and followers regularly engage with fitspiration posts on Instagram, to inspire others and to be inspired to exercise (respectively). Their reports also suggest that fitspiration provides accountability for exercise and education about fitness, and show that preferences for the messaging in posts differs between fitstagrammers and followers and between women and men. Across these reasons and preferences, however, both women and men who engage with fitspiration recognized that its effects are not universally positive, which is consistent with a subset of existing work (Easton et al., 2018; Fatt et al., 2019; Tiggemann and Zaccardo, 2016). By providing this and additional insight into the intentions of fitstagrammers, the perceptions of their followers, and each type of user’s preferences and reactions to various types of posts, the present study represents one of several necessary steps toward harnessing the potential of fitspiration to promote health.

For example, respondents’ reports of engagement with fitspiration show longstanding and frequent commitment, in the forms of posting and viewing multiple times per week for a year or more. Followers who reported viewing fitspiration posts more (vs. less) often also reported exercising more frequently. Yet the accuracy of the health information shared via fitspiration is unclear; many online communities share health information that is inaccurate (Gage-Bouchard et al., 2018), and there is little information available to verify the accuracy of fitness recommendations made via fitspiration. Such verification will be an important step for future work. Fitspiration may represent an opportunity to improve the promotion of healthy behaviour and self-image among young adults, as exposure to the trend is already an embedded habit for many.

Consistent with limited existing work among both men and women (e.g., Easton et al., 2018), women in the present study were more likely to report feeling negative while viewing fitspiration. Importantly, however, meaningful subsets of both women and men in the present study reported feeling somewhat negative after viewing fitspiration, and negative responses were prevalent among both fitstagrammers and followers. Important next steps for this work will be to clarify the nature of these negative responses (e.g., with respect to body satisfaction, mood, and exercise behavior) and associated gender differences, and to address the unique needs of women and men with respect to fitspiration consumption and intervention potential.

Although the measure used in this study did not ask respondents to specify the nature of these negative consequences, though previous work focused on exposure to body and fitness ideals indicates that there can be both immediate and longer-term effects on body satisfaction, eating and exercise behaviour, and broader self-perceptions (Holland and Tiggemann, 2017; Robinson et al., 2017). One pathway through which fitspiration can affect outcomes is that its images can activate social comparison processes, whereby viewers evaluate themselves (i.e., their fitness, body shape, and/or health habits) relative to individuals in social media images (Fardouly and Vartanian, 2016; Festinger, 1954). The individuals in these images are likely to represent upward comparison targets, perceived to be “doing better” than the viewer in the comparison domain. Upward comparisons can be inspiring, by providing evidence that a relevant other has achieved a valued goal and information about how the comparer may achieve that goal. Yet these comparisons often are discouraging, as they highlight the target’s superiority and the distance between the viewer and a valued goal (Arigo et al., 2015; Buunk and Ybema, 1997). As fitspiration consumers continue to engage with the trend despite experiencing negative consequences, however, it will be critical for future research to determine for whom and when negative consequences are most likely, to design effective intervention approaches (both within and beyond social media).

For instance, the present findings also showed significant differences in preferences between subgroups of respondents. Fitstagrammers showed a preference for posts that emphasize the physical results of exercise, while their followers indicated a preference to see posts that emphasize effort. Men also reported a preference for an image that focused on the benefits of not quitting, while women chose an image that focused on the benefits of efforts to exercise. These distinctions may be critical to understanding which posts may be beneficial versus detrimental. Too much exposure to fitstagrammers with a focus only on their physical fitness or posts accompanied by aversive messaging may eventually discourage engagement, or promote unhealthy behaviours (Grabe et al., 2008). It is not yet clear whether exposure to preferred images/posts, versus posts that are not matched to such preferences, would lead to improved exercise behaviour among those who are insufficiently active. As with other modalities, tailoring health promotion messages on social media to meet the distinct needs of user subgroups (e.g., women vs. men) may increase their effectiveness (cf. Broekhuizen et al., 2012), though there is need for further work in this area.

Strengths, Limitations, and Additional Future Directions

Strengths of the present study were its recruitment of both fitspiration followers and fitstagrammers, recruitment of both men and women, and its emphasis on the variety of possible effects of fitspiration. Previous research has examined the consequences of exposure to fitspiration, but has not compared the preferences and perceptions of individuals who post and voluntarily view its content. Results of this study expand our understanding of the fitspiration trend as it is perceived by users, which may be informative for future intervention and public health efforts. This study also examines men’s experiences with fitspiration. There has been little focus on men’s social media experiences in the health domain; inclusion of both women and men in the current study allowed for more comprehensive conclusions about fitstagrammers and followers, as well as comparisons between genders. Assessments were designed to capture the wide variety of potential motivations for and responses to fitspiration engagement, and provide insight into the range of experiences for young adults who engage with the trend.

The current study also had noteworthy limitations. This study focused only on exercise-related fitspiration; as this trend also encompasses posts about healthy eating and other health topics, these findings are relevant to only a portion of fitspiration’s breadth. Data were collected exclusively via self-report at a single time point. As such, information such as the frequency of participants’ engagement with fitspiration or engagement in physical activity may be inaccurate, and reports of respondents’ aggregated experiences may mask important day-to-day or moment-to-moment variability in motivation for posting/following and reactions to fitspiration messages. Future work using insensitive longitudinal methods (e.g., daily diaries, ecological momentary assessment) – particularly work that also tracks participant logins to Instagram or time spent on the app – would be useful for verifying participants reports and clarifying between- and within-person variability in fitspiration exposure and consequences. Responses were gathered using a measure created for this study, as no validated tool exists for capturing this information. Development of a validated tool to assess response to fitspiration posts would increase the reliability and accuracy of future work in this area.

In addition, recruitment of fitstagrammers relied on the “direct message” tool on Instagram. Although this was selected as the most likely avenue to enrolling fitstagrammers, an alternate recruitment method may have produced a more representative sample. Similarly, recruiting young adults who already follow fitspiration provided insight into the patterns and preferences of a subset of social media users. As many of these users report engaging in exercise 3–6 times per week, however, it cannot yet be determined (1) whether exposure to fitspiration promotes exercise among these users (vs. merely co-occurs among regular exercisers), or (2) whether greater exposure to fitspiration among low-active young adults would lead to increased exercise. Given the potential negative consequences of (self-selected) viewing of fitspiration posts, it is critical for future research to investigate the potential benefits of fitspiration while carefully considering its drawbacks.

Conclusions

Fitstagrammers’ intentions to motivate and inspire others are appealing to many followers, and in general, their intentions appear to match the benefits that followers perceive. Strong commitment to fitspiration posting and viewing in daily life, as observed in this study, may present opportunities for accurate and positive health communication. However, this study provides additional evidence of the potential negative consequences of fitspiration (which occur among both women and men), and indicates key content preferences among user subgroups. Although followers continue to engage with fitspiration despite potential mismatches between preferred and provided content, repeated exposure to nonpreferred content may potentiate negative consequences. Additional research to elucidate the conditions under which women and men benefit from fitspiration, and how best to harness these conditions in interventions, will inform health promotion efforts for young adults.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kristen Pasko, B.S., Zuhri Outland, B..S., Marissa DeStefano, B.S., Elena DiLorenzo, Madison Montalbano, and Nicole Plantier, B.S. for their assistance with recruitment and data collection.

This work was supported by a Presidential Summer Fellowship at The University of Scranton, awarded to the first author. The second author’s time was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; K23HL136657).

Contributor Information

Sabrina DiBisceglie, Department of Psychology, The University of Scranton; Scranton, PA, USA

Danielle Arigo, Department of Psychology, Rowan University; Glassboro, NJ, USA.

References

- Arigo D, Smyth JM and Suls JM (2015) Perceptions of similarity and response to selected comparison targets in type 2 diabetes. Psychology & Health 30: 1206–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boepple L, and Thompson JK (2016) A content analytic comparison of fitspiration and thinspiration websites. International Journal of Eating Disorders 49: 98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boepple L, Ata RN, Rum R and Thompson JK (2016) Strong is the new skinny: A content analysis of fitspiration websites. Body Image 17: 132–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekhuizen K, Kroeze W, van Poppel MN, Oenema A, and Brug J (2012). A systematic review of randomized controlled trials on the effectiveness of computer-tailored physical activity and dietary behavior promotion programs: An update. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 44: 259–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP, Collins RL, Taylor SE, VanYperen NW and Dakof GA (1990) The affective consequences of social comparison: either direction has its ups and downs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59: 1238–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffey D (2019) Global social media research summary 2019. [online] Smart Insights. Available at: https://www.smartinsights.com/social-media-marketing/social-media-strategy/new-global-social-media-research/ (accessed 17 March 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Deighton-Smith N and Bell BT (2018) Objectifying fitness: A content and thematic analysis of #fitspiration images on social media. Psychology of Popular Media Culture 7(4): 467–483. [Google Scholar]

- DiBartolo PM, Lin L, Montoya S, Neal H and Shaffer C (2007) Are there “healthy” and “unhealthy” reasons for exercise? Examining individual differences in exercise motivations using the function of exercise scale. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 1: 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Easton S, Morton K, Tappy Z, Francis D, and Dennison L (2018) Young people’s experiences of viewing the fitspiration social media trend: Qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 20(6): e219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fardouly J and Vartanian LR (2016) Social media and body image concerns: Current research and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology 9: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fatt SJ, Fardouly J and Rapee RM (2019) #malefitspo: Links between viewing fitspiration posts, muscular-ideal internalization, appearance comparisons, body satisfaction, and exercise motivation in men. New Media & Society: advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L (1954) A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations 7: 117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Gage-Bouchard EA, LaValley S, Warunek M, Beaupin L, and Mollica M (2018) Is cancer information exchanged on social media scientifically accurate? Journal of Cancer Education 33(6): 1328–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaznavi J, and Taylor LD (2015) Bones, body parts, and sex appeal: An analysis of #thinspiration images on popular social media. Body Image 14: 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves SF and Gomes AR (2012) Exercising for weight and shape reasons vs. health control reasons: The impact on eating disturbance and psychological functioning. Eating Behaviors 13: 127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabe S, Ward LM and Hyde JS (2008) The role of the media in body image concerns among women: a meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin 134: 460–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland G and Tiggemann M (2017) “Strong beats skinny every time”: Disordered eating and compulsive exercise in women who post fitspiration on Instagram. International Journal of Eating Disorders 50: 76–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judkis M (2012) Instagram bans ‘Thinspiration’ pro-eating disorder images. Available at: www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/arts-post(accessed 15 July 2019).

- Pew Research Center (2018) Social media fact sheet. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/ (accessed 17 March 2019).

- Prichard I, McLachlan AC, Lavis T, and Tiggemann M (2018) The impact of different forms of #fitspiration imagery on body image, mood, and self-objectification among young women. Sex Roles 78 (11–12): 789–798. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson L, Prichard I, Nikolaidis A, Drummond C, Drummond M and Tiggemann M (2017) Idealised media images: The effect of fitspiration imagery on body satisfaction and exercise behaviour. Body Image 22: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater A, Varsani N, and Diedrichs PC (2017) # fitspo or# loveyourself? The impact of fitspiration and self-compassion Instagram images on women’s body image, self-compassion, and mood. Body Image 22: 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot CV, Gavin J, Van Steen T, and Morey Y (2017). A content analysis of thinspiration, fitspiration, and bonespiration imagery on social media. Journal of Eating Disorders 5: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann M and Zaccardo M (2015) Exercise to be fit, not skinny: The effect of fitspiration imagery on women’s body image. Body Image 15: 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann M and Zaccardo M (2016) Strong is the new skinny: A content analysis of #fitspiration images on Instagram. Journal of Health Psychology 23(8): 1003–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]