Abstract

Solid organ transplantation is the treatment of choice for end stage organ failure. Parents of pediatric transplant recipients who reported a lack of readiness for discharge had more difficulty coping and managing their child’s medically complex care at home. In this paper, we describe the protocol for the pilot study of a mHealth intervention (myFAMI). The myFAMI intervention is based on the Individual and Family Self-Management Theory and focuses on family self-management of pediatric transplant recipients at home. The purpose of the pilot study is to test the feasibility of the myFAMI intervention with family members of pediatric transplant recipients and to test the preliminary efficacy on post-discharge coping through a randomized controlled trial. The sample will include 40 family units, 20 in each arm of the study, from three pediatric transplant centers in the United States. Results from this study may advance nursing science by providing insight for the use of mHealth to facilitate patient/family-nurse communication and family self-management behaviors for family members of pediatric transplant recipients.

Keywords: Pediatric, Self-Management, mHealth, Transplant

Solid organ transplantation, formerly a last option for terminally ill children, is now the treatment of choice for serious conditions that result in end stage organ failure. In 2018, nearly 2,000 children in the Unites States received an organ transplant (The Organ Procurement and Transplant Network, 2018). Although not extensively examined in the pediatric or transplantation populations, focused discharge transition plans have resulted in improved health status and decreased use of healthcare resources including hospital readmissions and costs of care in adults (Jack et al., 2009; Naylor et al., 1999; Naylor et al., 2004).

Improving the discharge transition process is a priority of the National Academy of Medicine (Institute of Medicine, 2001). In our previous multicenter research, we investigated the discharge transition process and post-discharge proximal and distal outcomes (e.g., hospital readmission and family quality of life) for parents of pediatric transplant recipients (Lerret & Weiss, 2011; Lerret et al., 2015). During the discharge transition process, parents who reported a lack of readiness for discharge had more difficulty coping and managing their child’s medically complex care at home (Lerret & Weiss, 2011; Lerret et al., 2014).

The at home daily management of a child following a transplant is multifaceted including precise administration of multiple medications throughout the day and other care processes such as management of abdominal drains and enteral tube feeding and/or central line care. Furthermore, families are managing follow-up care for laboratory and clinic appointments on average of three times per week. The complexity of transplant patients during ongoing recovery at home places them at risk for readmission in the first 30-days following hospital discharge (McAdams-Demarco, Grams, Hall, Coresh, & Segev, 2012; Patel, Mohebali, Shah, Markmann, & Vagefi, 2016).

Additional stressors for parents of pediatric transplant recipients include worry about medically-related complications, balancing the child’s medical care with family routines, role strain, and uncertainty for the child’s future (Lerret, Haglund, & Johnson, 2016; Lerret, Johnson, & Haglund, 2017; Lerret et al., 2014). Family self-management following transplant is a key consideration for post-discharge outcomes as families experience multiple psychosocial needs and parents report symptoms of emotional trauma (Benning & Smith, 1994; Stuber, Shemesh, & Saxe, 2003; Young, 2003). For this study, family self-management is the family’s management of and response to the child’s condition. For parents to provide adequate complex care to the child, it is critical that these challenges be not only identified (Shemesh, 2008) but also directly addressed.

Focused and frequent contact through the use of mobile devices (mHealth) improves health outcomes for medically complex adult patients (Naylor, Aiken, Kurtzman, Olds, & Hirschman, 2011; Slaper & Conkol, 2014; West, 2012). For instance, self-management strategies were enhanced in the adult lung transplant population utilizing an mHealth intervention (DeVito Dabbs et al., 2016) These national discharge transition projects, however, have not included children with chronic illness and their families.

We purport that family management of pediatric heart, kidney, and liver transplant recipients at home can be enhanced by a family self-management intervention using mHealth. Solid organ transplant has been identified as an ideal population to utilize and perform mHealth research due to the importance of patient engagement for medication and symptom management (Fleming, Taber, McElligott, McGillicuddy, & Treiber, 2017). Furthermore, family research experts have emphasized the role of utilizing a family theory based intervention for sound research (Knafl et al., 2017). In the current study, we use mHealth technology to offer a low-cost and efficient strategy for providing focused health-related messages as well as ongoing support and education (Park & Jayaraman, 2003; Sorber et al., 2012).

In this pilot study, a family self-management intervention (myFAMI) uses mHealth technology to facilitate and support family management of the child and communication between the family members and the healthcare team. myFAMI is indicated because it engages individual family members by gathering data in real time increments. Use of mHealth technology enhances access to the healthcare team by providing an additional means of communication, offering the opportunity for proactive intervention including additional support and education to optimize family self-management. The ability to identify factors that are predictive of decreased family coping and difficulty managing the child’s treatment regimen provides an opportunity to develop additional effective individualized family-centered interventions that have significant implications for care decisions, complications, and healthcare costs.

To our knowledge, this is the first research using mHealth technology to enhance the post-discharge transition experience and outcomes for family members of pediatric transplant recipients. This approach supports the concept of an interactive partnership between family members and the healthcare team that is a hallmark of patient and family centered care and a requisite for care coordination in complex care situations such as the transition from hospital to home (National Coalition on Care Coordination, December 2008).

Family Self-Management Theory

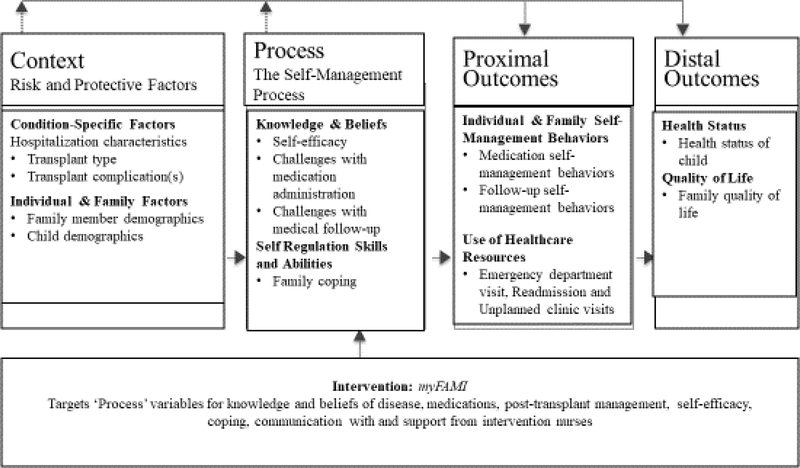

Using the Individual and Family Self-Management Theory as a guide (Ryan & Sawin, 2009), we are evaluating the efficacy of a family self-management intervention that uses a mHealth approach as a strategy for improving the discharge transition process. The Individual and Family Self-Management Theory contains four major constructs including context (risk and protective factors), process (the self-management process), proximal outcomes, and distal outcomes. The study concepts that coincide with each of the major constructs are displayed in Figure 1 (Ryan & Sawin, 2014). We are implementing this intervention via a Smartphone application (app) called the Family Self-Management Intervention (myFAMI) for family members of pediatric transplant recipients (heart, kidney, and liver transplant).

Figure 1.

Individual and family self-management theory applied to pediatric transplant. Adapted and retrieved from https://uwm.edu/nursing/about/centers-institutes/self-management/theory.cfm Adapted with permission of the author, holder of the copyright.

Study Purposes

The purpose of this paper is to describe the protocol used to achieve the pilot study aims. In this pilot study we are evaluating the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of myFAMI. For aim 1, we will determine the feasibility of family member use of myFAMI. For aim 2, we will determine the feasibility of nurse responses to trigger alerts identified by myFAMI family members. For aim 3, we will determine the preliminary efficacy of myFAMI in improving a single target outcome of family coping with additional analyses for potential impact on self-efficacy, family self-management behaviors for medication and medical follow-up, management of child transplant symptoms, use of healthcare resources, and family quality of life (QOL) for the primary family member. For aim 4, we will explore the feasibility and preliminary efficacy for the secondary family member and the family unit as a dyad.

Methods

Study Design

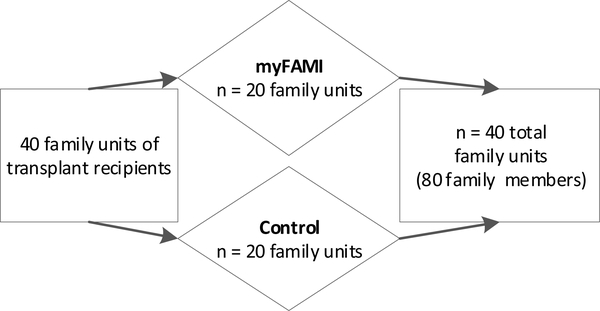

In this ongoing study, the team employs a randomized controlled trial design comparing the mHealth intervention (myFAMI) with standard post-discharge follow-up care. Family units are defined as a primary and secondary family member (e.g., mother, father, grandmother, and/or anyone identified as ‘related’ to the family). The family unit (primary and secondary family member) is randomly assigned to one of two groups, the myFAMI intervention (n = 20) or control (n = 20). The family unit includes two family members, yielding 40 family members in each group (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Study Enrollment Description

Note. myFAMI = study intervention

Randomization

Participants are randomized to the intervention (myFAMI) or control group based on a standard randomization table created by the study biostatistician. One member of the study team randomizes each family unit through REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) after consent/assent is obtained. We randomize prior to baseline data collection to minimize burden to the family on the day of hospital discharge. In this protocol, we do not randomize for transplant center, race/ethnicity, education level, or income due to the small sample size.

Study Setting

The family unit of 40 pediatric heart, kidney, or liver transplant recipients from three major U.S. pediatric transplant centers are being recruited, consented, and randomly assigned to one of two groups (myFAMI vs. control). The decision to recruit family members from three types of transplant populations will allow the acquisition of a sufficient sample in a limited time frame for this complex pediatric surgery and high-risk population. In two prior studies by Lerret and colleagues (Lerret & Weiss, 2011; Lerret et al., 2015), differences of post-discharge coping and family self-management difficulty and impact on family were not statistically significant among transplant types. Although the transplanted organ is not the same, the challenging management issues after hospital discharge are similar as family members monitor for symptoms, manage multiple daily medications, and organize frequent medical follow-up appointments. The focused family self-management components of the intervention are not organ specific.

Institutional review board approval at each individual transplant center was obtained before enrolling participants. The transplant team at each center screens for eligible participants and approaches them to assess their potential interest for participation in the study. Informed consent and assent are obtained before study procedures occur. Participants receive a stipend for participation and completion of study related materials. Both groups receive $50 for two data collection time points (baseline and end of study). The intervention group receives an additional $25 for completing the daily app and speaking to the study nurse in response to trigger alerts.

Participants

The study was powered to address the preliminary efficacy aim and based on the number of primary family members for the post-discharge coping difficulty measure, the target of the intervention. At an alpha of 0.05, with 20 in each group and a potential dropout of 10% we will have at least 18 in each group and at least 80% power to detect a difference of 0.9 standard deviations which is a moderate to large effect size.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

Family members are eligible for participation if they are: (1) English speaking (to date the instruments being used in this pilot have been validated for English speaking participants only); (2) 18 years of age or older; and (3) have a pediatric family member (< 18 years old) who has undergone a heart, kidney, or liver transplant who is being discharged home from the hospital. The secondary family member may be an aunt, uncle, grandparent, or other person considered to be family, if designated for participation by a parent..

Family members are ineligible for participation if: (1) there is the presence of significant communication or cognitive impairment that would preclude completion of questionnaires based on self-report or (2) the pediatric family member has experienced a previous transplant (to minimize the experiential effect). Participants unable to speak and read English are excluded due to the lack of resources to develop the app and communicate via video call in different languages.

The myFAMI Intervention

The myFAMI app was developed based on the first author’s previous work that identified a need for ongoing education and support specifically in the first month following hospital discharge as family members are trying to develop a new routine that allows for accurate medication administration and attending all medical follow-up appointments (Lerret et al., 2017; Lerret et al., 2014). Parents also reported how conversations with the medical team positively influenced their ability to cope and build their confidence (Lerret et al., 2014). The app was further refined with feedback from transplant experts and parents of pediatric transplant recipients who commented on app content and duration of follow-up following hospital discharge.

The myFAMI intervention includes an app to promote daily communication, initiated by an in-app notification or prompt, for 30 days following hospital discharge. The in-app notification or prompt serves as a reminder for each family member to open the myFAMI app and answer seven questions. Each family member is asked to rate his/her coping, beliefs about complex care at home (difficulty with medication administration and difficulty managing the medical follow-up regimen), and management of the child’s transplant symptoms (fever, pain, vomiting, diarrhea, other illness). These questions take less than two minutes to complete. The app closes after the family member answers the seven questions and responses are sent to the server by the app which are visible on a dashboard of a web application. Pre-identified critical responses, defined as triggers, result in immediate notification through the app to the intervention nurse by email and pager. The intervention nurse responds within two hours to each family member by either videoconference or a telephone to discuss the trigger alert generated by the family member response.

The intervention group for all study sites is managed by the four Pediatric Translational Research Unit’s (TRU) intervention nurses at the primary institution during regular business hours. The Principal Investigator, who is a transplant Advanced Practice Nurse, is the intervention nurse on weekends and holidays. The four TRU nurses are not informed of intervention or control group assignments. The intervention nurses received training from the PI for post-transplant management and on the use of the standardized script for each trigger. This training included role playing the standardized script and for how to respond to the family member(s). Intervention nurses were trained on how to maintain a log including detailed notes on each trigger alert generated and individual family member response. See Table 1 for the seven questions, possible responses, and pre-identified triggers that result in notification to the intervention nurse.

Table 1.

Daily Questions on myFAMI App

| Question Number | Family Member Question | Family Member Response Options | Trigger |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–5 | Is your child experiencing fever, pain, vomiting, diarrhea, other illness? |

Yes/No/Don’t Know | Yes/Don’t Know |

| If answer ‘Yes’ or ‘Don’t Know’ to questions 1–5, then family member will be asked the following: | |||

| “Please provide additional information regarding (fever, vomiting, etc). I have: 1) not done anything different, 2) administered a medication, 3) changed the diet, 4) done something else” | |||

| 6 | On a scale of zero to ten, how much difficulty are you having coping at home? | 0 = no difficulty 10 = great deal of difficulty | ≥ 3 |

| 7 | On a scale of zero to ten, how much difficulty are you having giving the medications at home? | 0 = no difficulty 10 = great deal of difficulty | ≥ 3 |

Study Procedures.

The control and intervention groups receive standard care including transplant educational materials, medication teaching sheets detailing side effects, and teaching by all members of the transplant team (pharmacists, physicians, nutritionists, and nurses) before hospital discharge. Information regarding symptoms (i.e., fever, vomiting, diarrhea, pain, illness symptoms) and when to call the transplant team are included in the study educational materials. Ongoing education occurs as part of standard post-discharge care during clinic appointments. Family members assigned to the control group (standard care) receive standard post-discharge follow-up care consisting of discharge education during the transplant hospitalization and at regularly scheduled appointments where they are instructed to contact the transplant team with problems or questions.

In addition to the current standard care, the myFAMI intervention group has the app downloaded to their personal or study provided smartphone by a trained research assistant at each site. Each of the two family members involved in the study receives orientation on use of the app by the research assistant and an informational resource sheet. Each morning, for the first 30-days following hospital discharge, each individual family member in the study receives an in-app notification or prompt at 8 a.m. local time and is asked to answer the seven daily questions within 2 hours (by 10 a.m.). In the event of a trigger alert, the intervention nurse responds within 2 hours until 5pm local time via a phone call and asks the family member to use the videoconference app for face-to-face interaction. Family members within the same family unit may answer questions differently and that may result in different triggers. Each of the two study family members is contacted individually by the intervention nurse after a trigger alert. The family member can accept a videoconference call or choose to have the conversation over the phone. The intervention nurse records the length of time between trigger alert and response. If the family member does not answer, the nurse leaves a voicemail message requesting the family member return the call to complete the conversation and discuss the trigger alert(s).

The intervention nurse uses a standardized script when responding to a trigger. The videoconference call is encouraged when responding to a trigger, but a telephone call is used when the family member is unable or unwilling to participate in videoconference. Videoconference call is preferred because it allows for the intervention to assess non-verbal cues, including facial expressions, that can only be identified via face-to-face contact. The intervention nurse responds to the identified trigger by providing guidance on self-management strategies. If more serious issues are identified, including but not limited to lethargy, severe pain, or signs of dehydration, the family member is directed to contact the Transplant Team for further medical evaluation of the child.

The family member who reports difficulty coping and/or managing the child’s medication regimen receives ongoing education and positive reinforcement based on the importance of building confidence (Lerret et al., 2014). The intervention nurse uses REDCap to record the time and content of the call including detailed notes on number, timing, reason, and action related to contact with the family member. The family member only receives a call from the intervention nurse if there is a trigger alert.

Fidelity of this intervention is addressed by use of a script to assure standard responses from each of the intervention nurses. The intervention nurse is asked to check each box of discussion items and sends this list to the PI for review to assure completeness and consistency of nurse and family member discussion. Additionally, the PI observes 25% of the conversations in real time using the same checklist. Comparisons are made between the PI and nurse completed checklists, and adjustments are made as needed to assure fidelity to the intervention.

A separate study team member completes the 30-day follow-up telephone interview and is blinded to the study assignment until the last set of questions that ask the intervention families experience with myFAMI. Families are asked to not share their group assignment with the transplant team.

Data Collection and Measurements

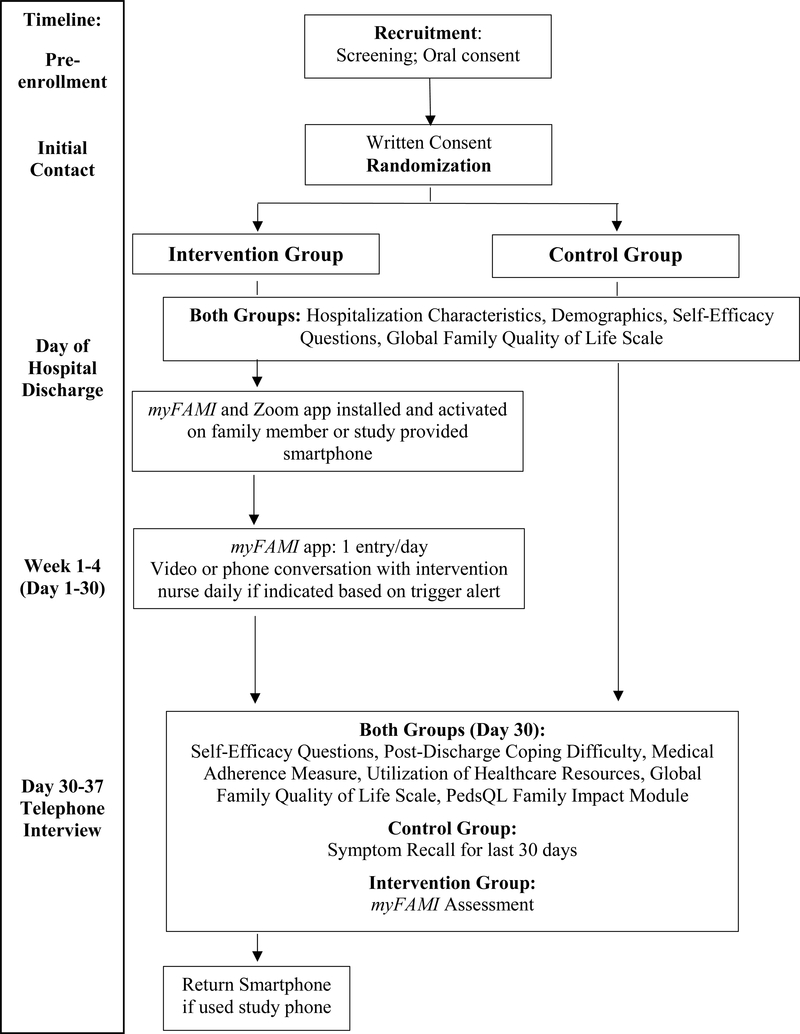

Data collection using REDCap occurs following informed consent and randomization. The control and intervention groups complete data collection at two time points, first on the day of hospital discharge and second, at a 30-day post-discharge telephone interview (Figure 3). The intervention group provides additional data by completing the app every day for 30 days following hospital discharge. Study procedures including study aims, time frames, concepts, measures, and data collection methods are outlined in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Data collection flow chart.

Note. myFAMI = study intervention, PedsQL = Pediatric Quality of Life

Table 2.

Study Concepts, Operational Measures and Data Collection Time Method

| Aim | Time Frame | Concept | Measure | Data Collection Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day of Hospital Discharge | Hospitalization Characteristics | Hospitalization Questions | Medical record review | |

| Family Member and Child Demographics | Demographics Questionnaire | Family member report | ||

| Self-Efficacy | Self-Efficacy Questions | Family member report | ||

| Family Quality of Life | Global Family Quality of Life Scale | Family member report | ||

| Aim 1 | Days 1–30(myFAMI group only) | Family Self-Management | Eight daily app questions | Family member report |

| Aim 2 | Days 1–30(myFAMI group only) | Trigger alert | Log number of triggers | Nurse |

| Trigger response | Log timing for reply to trigger | Nurse | ||

| Response to family | Log nurse response to family | Nurse | ||

| Aim 3 Aim 4 | Days 30–37 | Coping | Post Discharge Coping Difficulty Scale | Telephone interview |

| Family Self-Management Behaviors | Medical Adherence Measure | Telephone interview | ||

| Self-Efficacy | Self-Efficacy Questions | Telephone interview | ||

| Utilization of Healthcare Resources | Utilization questions | Telephone interview | ||

| Health Status of Child | Number of symptom days | Control = Telephone Intervention = App | ||

| Family Quality of Life | Global Family Quality of Life ScalePedsQL Family Impact Scale | Telephone interview | ||

| myFAMI Assessment | App experience questions | Intervention = Telephone | ||

Note. myFAMI = study intervention, PedsQL = Pediatric Quality of Life

Hospitalization Characteristics

Medical record review by the research assistant at each participating transplant center includes collecting data about the type of organ transplant, number of unplanned returns to the operating room, number of infections and/or episodes of rejection during the hospitalization, and the number of days hospitalized. In addition, information is retrieved from the medical record about the number of medications prescribed at the time of hospital discharge and the type of medical care required at home including, but not limited to, enteral tube feeding and central line maintenance.

Family Member and Child Demographics

Family member and child characteristics include age, race, and gender. Information about family member marital status as well as number of adults and children living in the home are also collected.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is evaluated using seven questions that measure how confident the family member feels managing various aspects of the child’s care. These questions were developed for this study. They are modeled after Lorig et al. and the PROMIS® database (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) and adapted for this population (Lorig & Holman, 2003; Moore et al., 2016; PROMIS, 2016). The two family member participants respond independently using a scale of 0–10 where a score of zero represents being not at all confident and a score of 10 represents being extremely confident. No reliability and validity data are available for the selected questions. A Cronbach’s alpha reliability score will be calculated for this sample.

Family Challenges

Family challenges are measured with two single item questions. Assessment of family member challenges with medication administration and difficulties with the medical follow-up regimen includes: (1) How much difficulty are you having giving your child the medications at home? and (2) How much difficulty are you having with attending lab and clinic appointments? Each question is answered using a 0–10 scale where ‘0’ indicates no difficulty and ‘10’ indicates great difficulty. Single item questions can reduce participant burden and be as effective as multi-item scales and are supported by construct and predictive validity (Sagrestano et al., 2002; Youngblut & Casper, 1993).

Family Coping

Coping is measured by the Post Discharge Coping Difficulty Scale. This measure captures family member difficulty coping with stress, recovery, self-care and management, support, confidence, and the child’s adjustment after hospital discharge(Weiss et al., 2008) This 10-item measure involves a scale of zero (not at all) to ten (extremely, completely or a great deal) where higher scores indicate that the family member is experiencing more difficulty coping. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability has ranged from 0.76 to 0.93 in samples of parents of hospitalized children, parents of transplant recipients, and in the adult population (Lerret & Weiss, 2011; Lerret et al., 2015; Weiss et al., 2008; Weiss, Yakusheva, & Bobay, 2010). Construct validity is supported by factor analysis and predictive validity is supported by the association of scores with higher post-discharge utilization of healthcare resources (Weiss et al., 2008).

Family Self-Management Behaviors

Using the Medical Adherence Measure, we identify patients at risk for problems with medication self-management behaviors. The measure has three modules including a focus on medications, nutrition, and clinic attendance. The two modules selected for this study were medications and clinic attendance as these are critical for early post-discharge monitoring after transplantation. The medication module assesses difficulty self-managing medication and the clinic attendance module assesses difficulty managing the follow-up regimen specific to clinic and laboratory visits (Zelikovsky & Schast, 2008). Family self-management difficulty is measured utilizing a dichotomous variable, difficulty (yes or no). Family members reporting any missed medications or appointments are classified as having difficulty self-managing at home.

Use of Healthcare Resources

Frequency of unplanned clinic appointments, emergency department visits, and hospital readmission data are gathered at the 30-day post-discharge interview as a yes/no response from family members. The responses are verified in the medical record (Lerret & Weiss, 2011; Lerret et al., 2015; Weiss et al., 2008).

Health Status of the Child

The child’s health status is measured by family member report of the child’s transplant symptoms. Symptoms are tracked in the app for the intervention group. Control group family members receive a symptom log to track symptoms and are asked to recall the number and type of symptoms during the post-discharge telephone interview.

Family Quality of Life

Two measures are used to assess family quality of life. The Global Family Quality of Life (GFQOL) is a 3-item instrument that asks the family to rate their child’s, their personal, and their family’s QOL on a scale of 0–100. Scores of zero represent poor family QOL, higher scores represent better family QOL, with scores of 100 representing excellent family QOL. Factor analysis using families of children with a complex health condition supported a one-dimensional scale. Construct validity was supported with moderate correlation (r = 0.39–0.57) and concurrent validity was established with measures of family resources and satisfaction. Internal reliability was high at Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86–0.90 (Ridosh, Sawin, Brei, & Schiffman, 2018).

The PedsQL Family Impact Module™ is a 36-item measure that uses a 5-point Likert scale. The instrument has a high Cronbach’s alpha of 0.97 and successfully differentiates between families who are at home or at a long-term care facility (Varni, Sherman, Burwinkle, Dickinson, & Dixon, 2004). This instrument has eight dimensions of parent and family functioning including physical, emotional, social, cognitive functioning, communication, worry, daily activities, and family relationships (Varni et al., 2004).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used to examine the demographic characteristics. Statistical software will include SPSS Version 24 and SAS 9.4 and Cytel suite for exact calculations.

For Aim 1, we will describe the use of the app using plots over time for the daily data collected in the mHealth application. The target completion rate for this study is a minimum of 80% of myFAMI family members completing daily questions for the 30-days, and 100% of control and myFAMI family members completing the 30-day post-discharge interview. Data will include frequency and timing for use of the app including the number of questions completed by the family member.

For Aim 2, we will describe the frequency of alerts initiated via the mHealth application and timing of the nurse response. Feasibility of the nurse response to a family member reported trigger generated by the app will be demonstrated by a minimum of an 80% response rate to the family member within two hours of the alert. We will also describe timing between the trigger alert and the nurse response to the family member. The nature of the trigger and summary of the nurse response will be summarized.

For Aim 3, we will evaluate preliminary efficacy for the primary caregiver by comparing control and intervention groups for the target study outcome of post-discharge coping. The target study outcome analysis will be conducted using a two-sample two-sided t-test. Additional analyses comparing self-efficacy, family self-management behaviors, and family QOL between the two groups will be completed using a two-sample two-sided t-test. Other analyses of child transplant symptoms and family management of child transplant symptoms, measured by number of symptom free days, and use of healthcare resources (ED visits and hospital re-admissions), will be compared between the two groups using a Fisher exact test and exact logistic regression.

For Aim 4, we will perform exploratory analysis for the primary and secondary family members as a dyad. The analysis of the dyad will use a mixed model approach with an autocorrelation variance covariance matrix structure. For measures with continuous variables for which the two family members provide separate answers (coping, self-efficacy, family self-management, quality of life), control and intervention comparisons will be accomplished by using a mixed-effect method with random family effects accounting for correlations between caregivers from the same family and group indicator as a fixed effect. Intra-class correlation will be estimated to assess similarities between caregivers from the same family. For the dichotomous variables for which each family only provides one answer (emergency department visit and hospital admission), we will use chi-square tests to assess for group effect. Odds ratios will also be estimated for these variables. A dyadic analysis expert will be consulted.

We intend to fully explore the concordance/discordance of responses within dyads and the relationship of each dyad member’s data to theoutcomes. The responses from the individual family members are expected to be correlated since they are caring for the same child. We therefore intend to build a correlation structure using a hierarchical approach such as a mixed model with dyad nested within the family.

Discussion

Progress to Date

Family member recruitment began in October 2018 at Site A, November 2018 at Site B, and June 2019 at Site C. To date, 21 transplant family units have been enrolled for a total of 42 family members (2 family members per transplant family unit). Ten family units (n = 20) were randomized to the intervention group and the remaining eleven family units (n = 22) were randomized to the control group. Recruitment will remain open until a total of 40 family units (N = 80 family members) are enrolled.

Challenges Encountered

One of the most challenging aspects of our study is participant recruitment. Being pediatric solid organ transplant recipients, the study population is unique and relatively small. The frequency of pediatric transplant is low, and the inclusion criteria are further limiting by including only English-speaking families. Three transplant recipient families were not eligible because the protocol originally stated that there needed to be both a primary and secondary family member to enroll. The protocol has been recently modified to include a family unit if only a primary family member is able or willing to enroll as the data analysis for the dyad and the secondary family member is exploratory only. Enrollment was originally planned for two centers, but a third center was added due to the lower than anticipated enrollment rate. A fourth major medical center is in the IRB approval process to expand recruitment.

A limitation to the study procedure is that randomization is completed before data collection which may add potential bias between the two groups. Future work with a fully powered study will allow for baseline data collection before randomization. Another challenge is maintaining the app program functionality, a critical consideration for this project. The computer science team has been charged with developing an update on two separate occasions within a short period of time to minimize the interruption of data collection. A strong collaboration with a computer science department for app management is critical for successful implementation and ongoing enrollment.

Lessons Learned

An important learning opportunity is the value of ongoing assessments of study recruitment and procedures. An astute awareness to even what may be considered a minor issue can be critical to making necessary adjustments to the study protocol. Attention to detail is important to meeting milestones on the project timeline. Reflection on the study process and timeline allows the team to consider improvements for future work. Future plans for this project include translation of this app to different languages so that it is accessible to more family members. Modifications to the app will also be considered based on intervention participant responses and may include in-app educational resources.

Summary

This is the first study known to us that evaluates an intervention, myFAMI, to improve family self-management for family members of children who received a heart, kidney, or liver transplant. The key outcome is assessing the preliminary efficacy of post-discharge coping. In this pilot study, we are also assessing the feasibility of myFAMI including daily family member use and intervention nurse response to potential trigger alerts generated by family member response. Furthermore, myFAMI also guides an evaluation to improve post-discharge outcomes including family coping, self-efficacy, family self-management behaviors for medications and medical follow-up, managing child transplant symptoms, decreasing use of healthcare resources, and improving family QOL.

This intervention highlights the key role nurses play in engaging and supporting families through ongoing teaching and confidence building that is enhanced with this intervention. Through this pilot study we focus on individual interventions for family members who may need to develop skills to manage the care of the child with a chronic condition but also provides an opportunity for future research to consider the family member’s physical and psychological health. The myFAMI study may advance nursing science concerning the family management of a complex chronic illness population in the home during the critical time period immediately following hospital discharge. The findings also may extend the science beyond the individual to include care for the caregivers – in this case the family.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to acknowledge Kathleen J. Sawin, PhD, CPNP-PC, FAAN, a co-developer of the theory used for this study, for her critical review and expert consultation of this manuscript.

Funding Information: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23NR017652

Contributor Information

Stacee M. Lerret, Associate Professor, Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Medical College of Wisconsin, 8701 Watertown Plank Road, Milwaukee, WI 53226.

Rosemary White-Traut, Director of Nursing Research, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin; Professor Emerita, University of Illinois of Chicago.

Barbara Medoff-Cooper, Professor Emerita, University of Pennsylvania.

Pippa Simpson, Professor of Pediatrics, Medical College of Wisconsin; Director of Quantitative Health Sciences.

Adib Riddhiman, Graduate Research Assistant; Department of Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science, Marquette University.

Ahamed Sheikh, Professor, Department of Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science, Marquette University.

Rachel Schiffman, Associate Dean for Research and Professor, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; Director, UWM Self-Management Science Center.

References

- Benning CR, & Smith A. (1994). Psychosocial needs of family members of liver transplant patients. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 8, 280–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVito Dabbs A, Song MK, Myers BA, Li R, Hawkins RP, Pilewski JM, … Dew MA (2016). A randomized controlled trial of a mobile health intervention to promote self-management after lung transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation, 16, 2172–2180. doi:DOI: 10.1016/j.ijmedinfo.2016.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JN, Taber DJ, McElligott J, McGillicuddy JW, & Treiber F. (2017). mHealth in solid organ transplant: The time is now. American Journal of Transplantation, 17, 2263–2276. doi:DOI: 10.1111/ajt.14225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, Greenwald JL, Sanchez GM, Johnson AE, … Culpepper L. (2009). A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: A randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 150, 178–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl KA, Havill NL, Leeman J, Fleming L, Crandell JL, & Sandelowski M. (2017). The nature of family engagment in interventions for children with chronic conditions. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 39, 690–723. doi:DOI: 10.1177/0193945916664700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerret SM, Haglund KA, & Johnson NL (2016). Parents’ perspectives on shared decision making for children with solid organ transplants. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 30, 374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerret SM, Johnson NL, & Haglund KA (2017). Parents’ perspectives on caring for children after solid organ transplant. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 22. doi: 10.1111/jspn.12178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerret SM, & Weiss ME (2011). Parents of pediatric solid organ transplant recipients and the transition from hospital to home following solid organ transplant. Pediatric Transplantation, 15, 606–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerret SM, Weiss ME, Stendahl G, Neighbors K, Amsden K, Lokar J, … Alonso EM (2014). Transition from hospital to home following pediatric solid organ transplant: Qualitative findings of parent experience. Pediatric Transplantation, 18, 527–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerret SM, Weiss ME, Stendahl GL, Chapman S, Menendez J, Williams L, … Simpson P. (2015). Pediatric solid organ transplant recipients: Transition to home and chronic illness care. Pediatric Transplantation, 19, 118–129. doi: 10.1111/petr.12397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K, & Holman H. (2003). Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 26, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams-Demarco MA, Grams ME, Hall EC, Coresh J, & Segev DL (2012). Early hospital readmission after kidney transplantation: patient and center-level associations. American Journal of Transplantation, 12, 3283–3288. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SM, Schiffman RF, Waldrop-Valverde D, Redeker NS, McCloskey DJ, Kim MT, … Grady P. (2016). Recommendations of common data elements to advance the science of self-management of chronic conditions. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 48, 437–447. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Coalition on Care Coordination. (December 2008). Toward a care coordination policy for America’s older adults. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor MD, Aiken LH, Kurtzman ET, Olds DM, & Hirschman KB (2011). The importance of transition care in achieving health reform. Health Affairs, 30, 746–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, Jacobsen BS, Mezey MD, Pauly MV, & Schwartz JS (1999). Comprehensive discharge planning and follow-up of hospitalized elders: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 281, 613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, & Schwartz JS (2004). Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52, 675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, & Jayaraman S. (2003). Enhancing the quality of life through wearable technology. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine, 22, 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MS, Mohebali J, Shah JA, Markmann JF, & Vagefi PA (2016). Readmission following liver transplantation: an unwanted occurrence but an opportunity to act. HPB (Oxford), 18, 936–942. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PROMIS N. (2016). Self-efficacy for managing chronic conditions. Retrieved June 12, 2019 http://www.nihpromis.org

- Ridosh MM, Sawin KJ, Brei TJ, & Schiffman RF (2018). A global family quality of life scale: Preliminary psychometric evidence. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine: An Interdisciiplinary Approach, 11, 103–114. doi:DOI. 10.3233/PRM-170477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan P, & Sawin KJ (2009). The individual and family self-management theory: Background and perspectives on context, process, and outcome. Nursing Outlook, 57, 217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan P, & Sawin KJ (2014). Individual and family self-management theory: Revised figure. Retrieved from http://www4.uwm.edu/nursing/about/centers-institutes/self-management/theory.cfm

- Sagrestano LM, Rodriguez AC, Carroll D, Bieniarz A, Greenberg A, Castro L, & Nuwayhid B. (2002). A comparison of standardized measures of psychosocial variables with single item screening measures used in an urban obstetric clinic. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 31, 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemesh E. (2008). Assessment and management of psychosocial challenges in pediatric liver transplantation. Liver Transplantation, 14, 1229–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaper MR, & Conkol K. (2014). mHealth tools for the pediatric patient centered medical home. Pediatric Annals, 43, 73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorber J, Shin M, Peterson R, Cornelius CM,S, Prasa A, & Kotz D. (2012). An amulet for trustworthy wearable mHealth. Paper presented at the Workshop on Mobile Computing Systems and Applications, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Stuber ML, Shemesh E, & Saxe GN (2003). Posttraumatic stress responses in children with life threatening illnesses. Child and Adolescent Psyciatirc Clinics of North America, 12, 195–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Organ Procurement and Transplant Network. (2018). Transplants in the U.S. by recipient age for organs. [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Sherman SA, Burwinkle TM, Dickinson PE, & Dixon P. (2004). The PedsQLTM family impact module: Preliminary reliability and validity. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2, Article 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M, Johnson NL, Malin S, Jerofke T, Lang C, & Sherburne E. (2008). Readiness for discharge in parents of hospitalized children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 23, 282–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M, Yakusheva O, & Bobay K. (2010). Nurse and patient perceptions of discharge readiness in relation to postdischarge utilization. Medical Care, 48, 482–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West D. (2012). How mobile devices are transforming healthcare. Issues in Technology Innovation, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Young GS, Mintzer LL, Seacor D, Castaneda M, Mesrkhani V, & Stuber ML (2003). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in parents of transplant recipients: Incidence, severity, and related factors. Pediatrics, 111, 725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngblut JM, & Casper GR (1993). Single item indicators in nursing research. Research in Nursing and Health, 16, 459–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelikovsky N, & Schast AP (2008). Eliciting accurate reports of adherence in a clinical interview: Development of the medical adherence measure. Pediatric Nursing, 34, 141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]