Abstract

Background:

Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is one of the most common chronic diseases in the world. As a disease with long term complications requiring changes in management, DM requires not only education at the time of diagnosis, but ongoing diabetes self-management education and support (DSME/S). In the United States, however, only a small proportion of people with DM receive DSME/S, although evidence supports benefits of ongoing DSME/S. The diabetes education that providers deliver during follow up visits may be an important source for DSME/S for many people with DM.

Methods:

We collected 200 clinic notes of follow up visits for 100 adults with DM and studied the History of Present Illness (HPI) and Impression and Plan (I&P) sections. Using a codebook based on the seven principles of American Association of Diabetes Educators Self-Care Behaviors (AADE7), we conducted a multi-step deductive thematic analysis to determine the patterns of DSME/S information occurrence in clinic notes. Additionally, we used the Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) for investigating whether providers delivered DSME/S to people with DM based on patient characteristics.

Results:

During follow up visits, Monitoring was the most common self-care behavior mentioned in both HPI and I&P sections. Being Active was the least common self-care behavior mentioned in HPI section and Healthy Coping was the least common self-care behavior mentioned in I&P section. We found providers delivered more information on Healthy Eating to men compared to women in I&P section. Generally, providers delivered DSME/S to people with DM regardless of patient characteristics.

Conclusions:

This study focused on the frequency distribution of information providers delivered to the people with DM during follow up clinic visits based on the AADE7. The results may indicate a lack of patient-centered education when people with DM visit providers for ongoing management. Further studies are needed to identify the underlying reasons why providers have difficulty delivering patient-centered education.

Keywords: Diabetes Mellitus, Diabetes Education, Electronic Health Records, Guidelines, Self-Management

1. Introduction

There were 30.3 million Americans with diabetes mellitus (DM) in 2015, including 7.2 million people who were undiagnosed.1 Diabetes self-management education (DSME) is an organized process of teaching people with DM type 1 or DM type 2 to manage symptoms, treatments, and lifestyle changes associated with DM.2 Diabetes self-management support (DSMS) is defined as activities that help people with DM engage in behaviors needed for daily self-management.3 Diabetes self-management education and support (DSME/S) is a vital component for the management of people with DM.2 A systematic review reported that DSME/S helped to improve diabetes knowledge, record eating habits, and increase the frequency and accuracy of blood glucose monitoring in people with DM.4 It can also help to improve glycemic control2,4 and reduce risks for complications from DM.5

The American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE), American Diabetes Association (ADA), and Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics recommend that patients should visit a certified diabetes educator (CDE) when first diagnosed with diabetes and then annually to monitor their condition.6 Additional visits with a CDE are recommended if they experience complications or any time there is transition in their care.6 Health education is the cornerstone of a well-developed health care system. However, in the United States (US), access to diabetes education may be limited due to several barriers. Despite known benefits, Medicare, as well as most private insurance companies in the US provide DSME/S to only a small percentage of people with DM.7 Consequently, only 5% of Medicare beneficiaries and 6.8% of privately insured people with newly diagnosed DM participate in DSME/S.8,9 The reasons behind limited utilization of DSME/S may include poor understanding of the necessity and effectiveness of DSME/S, confusion regarding when and how to make referrals for physicians, and lack of access to DSME/S services and support from family.10 Limitation in number of visits to a CDE prevents patients from getting timely and continuous support from the CDEs.11,12

Considering the access barriers to DSME/S by a CDE, the diabetes education that health care providers deliver during clinic visits may be the only source for DSME/S for many people with DM. Furthermore, a 2006 survey in the US, conducted by the Department of Health and Human services showed that receiving diabetes education and knowledge about the disease from providers was the most preferred method by people with DM.12 However, in a busy clinical environment, it is a challenge for providers to deliver DSME/S effectively during the limited visiting time.13–15 Based on the statistics portal “Statista”, only 11% of US primary care physicians spent 25 or more minutes with each patient in 2018.16 Administrative and documentation responsibilities may be another hindrance. After adopting a structured and standard electronic health record (EHR), the time that providers spent in consultation was decreased by 8.5%.17 Within the limited clinic time, a provider must review and document numerous clinic note sections.18 Consequently, the remaining time may be fragmented, and insufficient for providers to educate patients on individual DSME/S topics.

Patient-centered DSME is defined as “diabetes education that begins from the patients’ experience of their diabetes, their perspectives on its management, and its outcomes, and seek to increase the patients’ involvement in the management of their disease.”19 In collaboration with health providers, patients, and families, patient-centered education provides needed information to help patients make medical decisions and personalized self-management plans.20,21 Patient-centered education can benefit patients with DM, including improvement of blood glucose, total cholesterol, and body mass index (BMI).22–25

The AADE, which is a multi-disciplinary professional membership organization striving to improve care of diabetes through integrated education, management and support,26,27 developed patient-centered diabetes self-management education guidelines for people with DM. The guidelines are the seven principles of AADE7 Self-Care Behaviors (AADE7): Healthy Eating, Being Active, Monitoring, Taking Medication, Problem Solving, Reducing Risks, and Healthy Coping.28 AADE7 can help providers deliver the key points of DSME/S in an organized manner to patients with DM. People with DM type 1 or DM type 2 need individualized management plans. We chose AADE7 to conduct this clinic notes analysis because it is a structured, validated and widely accepted patient-centered self-management behaviors guidelines to provide the basis of DSME/S for people with DM type 1 or DM type 2 in the United States. They are also supported by the ADA and the American Geriatrics Society (AGS).7,29,30

There have been limited studies analyzing the clinic notes of people with DM.31–35 These studies focused on applying natural language processing (NLP) for information extraction, such as identifying people with type 2 DM with a specific phenotype,31 estimating the occurrence of hypoglycemia,32 and extracting the lab test results.35 However, limitations exists when NLP techniques were used in these studies, such as disagreement with manual classification,34 decreasing accuracy with semantically complex sentences,33,35 having difficulty distinguishing acronyms and abbreviations with different meanings,36 and demonstrating successes in specific research settings.37 Considering the lack of NLP applications for information discovery in diabetes education using EHR physician note sections, we opted to manually code clinic notes in this study as a feasibility study. We chose two sections in clinic notes, History of Present Illness (HPI) and Impression and Plan (I&P), to analyze the information providers deliver to people with DM. HPI and I&P are preferably not auto-populated, and are the sections where providers document patients’ previous self-management behaviors (HPI section) and suggestions for conducting self-management (I&P section).38 Increasingly, completed clinic notes are available for review by the patient and may provide an additional opportunity for DM education and support.39

The objective of this study was to investigate the frequency distribution of information providers deliver to people with DM during clinic visits based on the AADE7 guidelines by analyzing the HPI and I&P sections in clinic notes. We also aimed to investigate whether the providers delivered DSME/S to people with DM based on patient characteristics of sex, age group, geographic region, type of diabetes, history of diagnosis of diabetes, comorbidities (e.g. hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease), insulin treatment, BMI, and HbA1c.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

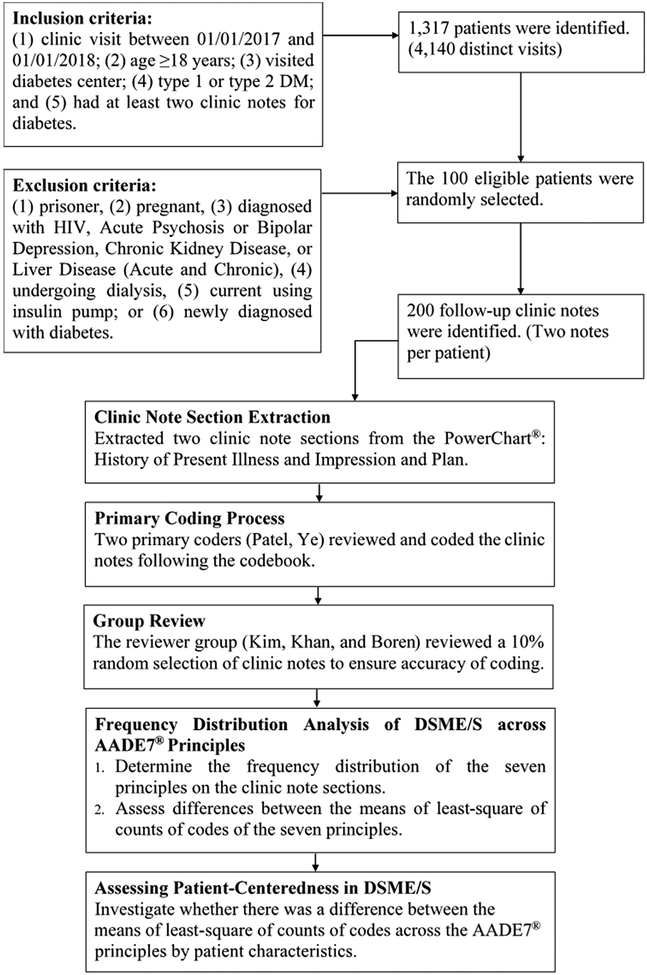

We conducted this qualitative study at the Cosmopolitan International Diabetes and Endocrinology Center (CIDEC) at University of Missouri Health Care (UMHC). Using a codebook created based on the AADE7, we first conducted a multi-step deductive thematic analysis via a systematic group review process to determine the frequency distribution of the counts of codes based on the AADE7 in the designated clinic note sections. Additionally, we conducted inferential statistics based on the counts of codes. We used Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM)40,41 to assess differences between the means of least-square of counts of codes of the seven AADE7 principles. Then, we conducted an inferential statistics analysis to verify whether providers delivered DSME/S to people with DM based on patient characteristics. Patient characteristics collected included sex, age group, geographic region, type of diabetes, history of diagnosis of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, insulin treatment, BMI, and HbA1c. Figure 1 depicts the data collection and data analysis process.

Figure 1.

Clinic notes collection and analysis process. We identified 100 patients’ 200 clinic notes after application of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Clinic note sections extracted from the PowerChart were coded and reviewed following the codebook to determine the frequency distribution of the American Association of Diabetes Educators Self-Care Behaviors (AADE7) principles on clinic notes. We used the Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) to assess differences between the means of least-square of counts of codes of the seven AADE7 principles. We also used GLMM to investigate whether there was a difference in documentation pattern across the AADE7 principles by patient characteristics.

2.2. Study Setting and Investigators

CIDEC at UMHC is recognized nationally for excellence in patient care and multidisciplinary research programs. During 2017, there were almost 6,600 visits for adults with type 1 or type 2 DM to the Diabetes Center. All patient information is maintained in electronic health records (EHR), PowerChart, a secure Cerner based program with access to all providers, and also to patients via a patient portal, HEALTHConnect. UMHC maintains PowerInsight, Cerner’s clinical reporting platform for the EHR,42 which allows effective patient selection for the data collection required by this study. The study team had interdisciplinary expertise including DM Education, health informatics, and clinical endocrinology.

2. 3. Subjects

Patient selection was conducted using PowerInsight, a secure portal which provides reports based on specific search criteria, such as medical record number, age, sex, admit date and time, diagnosis description, diagnosis code, provider, reason for visit, and clinic locations. We included patients who were 18 years or older and presented to CIDEC between January 1, 2017, 12:00 AM and January 1, 2018, 12:00 AM. Patients who were diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 DM, and had at least two clinic notes for follow up of DM during the study period were included. Patients were excluded if they were incarcerated, were pregnant, had known diagnosis of HIV, Acute Psychosis or Bipolar Depression, Chronic Kidney Disease, Liver Disease, or were undergoing dialysis. People with DM who were using insulin pumps were excluded since focused DSME/S is provided prior to initiating pump therapy and at each visit through a dedicated insulin pump clinic. We also excluded initial visit for diabetes because providers may provide more comprehensive DSME/S themselves or refer people who are newly diagnosed with diabetes to diabetes educators.

When computing the sample size for this study, we considered the qualitative nature of the study. We considered 200 notes of 100 patients which accounts for approximately 7.6% of the total patients who were 18 years or older at the study site to be an adequate sample size to answer the research questions we aimed to address in this pilot study. Based on the data saturation theory,43 we would add more patients into this study to increase the sample size if the frequency distribution of the seven principles changed significantly during review process. All data was de-identified to protect individually identifiable health information. This study was approved by the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board (IRB).

2. 4. Clinic Note Section Extraction

From PowerInsight, information regarding patients’ medical record number, sex, age, zip code, diagnosis description, diagnosis code, provider, and reason for visit was obtained. We removed duplicate records, applied the exclusion criteria and selected 100 patients by using simple random sampling. Utilizing PowerChart, the two clinic note sections: HPI and I&P were extracted, de-identified and copied into a Microsoft Word document for review and manual coding. Data was collected regarding specific patient characteristics including BMI, HbA1c, and information regarding co-morbid conditions including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease. We also included information whether they were taking insulin, and sharing glucose monitoring data with the providers at the time of the visit.

2. 5. Codebook Development

We adopted deductive thematic analysis44 for our study. Deductive thematic analysis is a theory driven approach, and its codes and themes were developed by existing concepts.45 Based on previous experience with a codebook used in our “Diabetes Mobile App Features Analysis Study”,46–48 the study team had developed a codebook by consulting the AADE7 guidelines for the most up-to-date education items.28 The research team (Kim, Khan, Boren, and Ye) reviewed and revised the codebook to ensure the final code set captures consistent and comprehensive diabetes education items for this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Codebook for clinic notes analysis and count in 200 clinic notes.

| Category | ID | Code | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Healthy Eating (257) | 1.1 | Develop an eating plan (how to plan a week of eating overall or how to plan each meal) | 19 |

| 1.2 | Set goals for healthy eating | 29 | |

| 1.3 | Remind to eat | 0 | |

| 1.4 | Provide Recipes | 0 | |

| 1.5 | Count carbohydrates | 31 | |

| 1.6 | Read food labels | 1 | |

| 1.7 | Prevent high or low blood sugar | 42 | |

| 1.8 | Measure each serving (know how much you should eat and don’t overdo it) | 2 | |

| 1.9 | Monitor eating (record what you eat and how much you eat) | 97 | |

| 1.10 | Provide knowledge of healthy eating | 35 | |

| 1.11 | Provide restaurants information | 0 | |

| 1.12 | Share record of eating through forum or email | 1 | |

| 2. Being Active (113) | 2.1 | Set exercise plan/goal | 24 |

| 2.2 | Remind to do exercise | 3 | |

| 2.3 | Choose activities (think of things you like to do) | 7 | |

| 2.4 | Start exercising (take it slow – start with five or 10 minutes of the activity and work your way up to 30 minutes at a time, five days a week) | 7 | |

| 2.5 | Do exercise at personal pace (don’t overdo it! While you exercise, you should be able to talk, but not sing) | 19 | |

| 2.6 | Check blood sugar level before and after exercise | 0 | |

| 2.7 | Keep track of activities | 44 | |

| 2.8 | Find a friend to exercise with | 0 | |

| 2.9 | Take a physical exercise class | 1 | |

| 2.10 | Join adult leagues | 0 | |

| 2.11 | Mix activities up (try a few different things so you don’t get bored) | 2 | |

| 2.12 | Provide knowledge of exercise | 6 | |

| 2.13 | Share record of exercise through forum or email | 0 | |

| 3. Monitoring (1,808) | 3.1 | Learn how to use the glucometer | 3 |

| 3.2 | Learn tips for the best/easiest way to monitor | 3 | |

| 3.3 | Learn when to check the blood sugar | 145 | |

| 3.4 | Learn what the results of blood sugar mean | 68 | |

| 3.5 | Learn what to do if the results of blood sugar are off target | 81 | |

| 3.6 | Learn how to record blood sugar results and keep track over time | 13 | |

| 3.7 | Set goals for blood sugar | 21 | |

| 3.8 | Monitor blood sugar levels | 267 | |

| 3.9 | Record the spot of blood sugar testing or insulin injection | 0 | |

| 3.10 | Provide knowledge of blood sugar | 10 | |

| 3.11 | Monitor lab test results (other than blood sugar, cholesterol, and urine testing) | 246 | |

| 3.12 | Monitor vital signs (other than blood pressure and pulse) | 0 | |

| 3.13 | Monitor heart health (blood pressure, pulse, weight, BMI, and cholesterol level) | 471 | |

| 3.14 | Monitor kidney health (urine and blood testing) | 244 | |

| 3.15 | Monitor eye health (eye exams) | 119 | |

| 3.16 | Monitor foot health (foot exams and sensory testing) | 45 | |

| 3.17 | Share record of blood sugar through forum or email | 72 | |

| 4. Taking Medication (680) | 4.1 | Learn why take these medications | 3 |

| 4.2 | Learn what will these medications do for patients | 3 | |

| 4.3 | Learn how to fit medications into the schedule | 3 | |

| 4.4 | Learn the side effects of these medications | 55 | |

| 4.5 | Learn what to do for side effects of medications | 10 | |

| 4.6 | Remember to take medications at the right time every day | 4 | |

| 4.7 | Remind to take medication | 2 | |

| 4.8 | Manage medication list | 348 | |

| 4.9 | Calculate recommended insulin dosage | 199 | |

| 4.10 | Rotate the sites if inject insulin (if the patient injects insulin, rotate the sites every day from the fattier part of the patient’s upper arm to outer thighs to buttocks to abdomen) | 2 | |

| 4.11 | Record medicine adherence | 49 | |

| 4.12 | Provide knowledge of medication | 2 | |

| 4.13 | Share record of medication through forum or email | 0 | |

| 5. Problem Solving (361) | 5.1 | Don’t beat self up (managing diabetes doesn’t mean being “perfect.”) | 0 |

| 5.2 | Analyze the day | 124 | |

| 5.3 | Learn from experience (Figure out how to correct the problem in a way that works best for the patient, and apply that to similar situations moving forward) | 29 | |

| 5.4 | Discuss possible solutions | 120 | |

| 5.5 | Try the new solutions (try the new solutions and then evaluate whether they are working for the patient) | 88 | |

| 5.6 | Use an alert or reminder for abnormal data | 0 | |

| 6. Reducing Risks (441) | 6.1 | Don’t smoke | 18 |

| 6.2 | See the doctor regularly (plan to see the doctor about every three months, unless told otherwise) | 186 | |

| 6.3 | Visit the eye doctor at least once a year | 110 | |

| 6.4 | See the dentist every six months | 5 | |

| 6.5 | Take care of the feet | 41 | |

| 6.6 | Listen to the body (if the patient doesn’t feel well, or something just doesn’t seem right, contact the doctor to help figure out what’s wrong, and what the patient should do about it) | 11 | |

| 6.7 | Provide knowledge of reducing risks | 41 | |

| 6.8 | Share information with a diabetes forum or American Diabetes Association website, etc., with the patient | 0 | |

| 6.9 | Vaccination | 29 | |

| 7. Healthy Coping (75) | 7.1 | Do exercise (when the patient is sad or worried about something, suggest going for a walk or bike ride. Research shows when people are active, the brain releases chemicals that make them feel better) | 2 |

| 7.2 | Participate in faith-based activities or meditation | 0 | |

| 7.3 | Pursue hobbies | 10 | |

| 7.4 | Attend support groups | 20 | |

| 7.5 | Thinking positive | 4 | |

| 7.6 | Being good to self | 13 | |

| 7.7 | Record mood | 25 | |

| 7.8 | Share knowledge of healthy coping | 1 |

Note: The total count of codes is 3,735. The most commonly occurring principle is Monitoring and least commonly occurring principle is Healthy Coping.

2.6. Coding Process

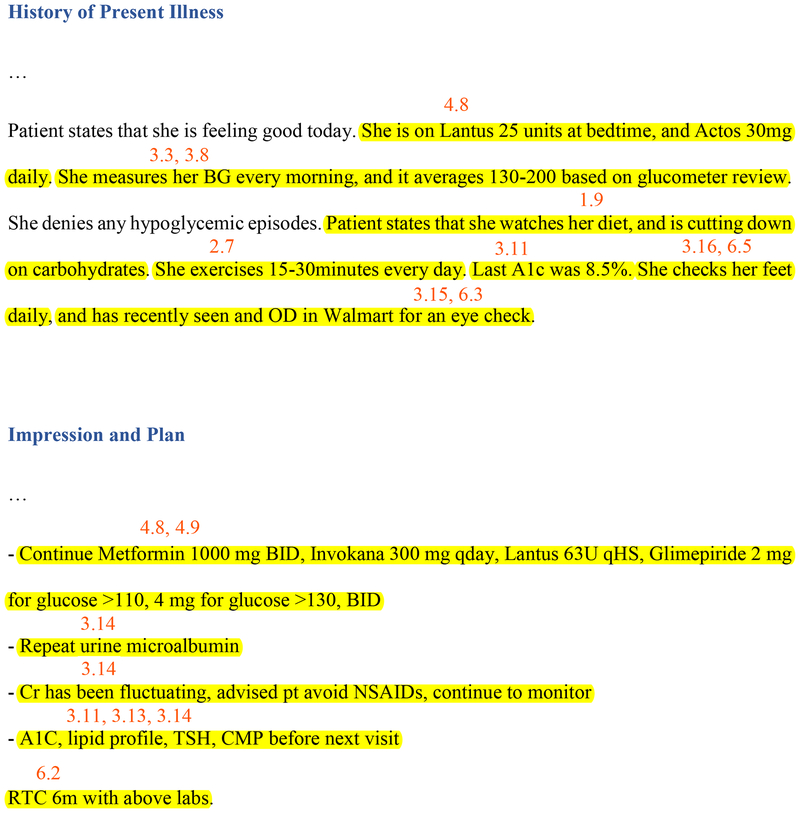

We employed a multi-step coding process over a 10-week period along with bi-weekly group reviews.49 Patel and Ye served as the primary coders. Three research group members (Kim, Khan, and Boren) served as reviewers of the primary coding to ensure accuracy. The coding algorithm involved the following steps: (1) identifying either sentences or words of education items as a unit of analysis in the clinic note sections, (2) determining the codes that matched the concept of the education items from the codebook, (3) marking the code IDs on the extracted clinic note sections, and (4) entering IDs and comments into a spreadsheet for a retrospective analysis. Figure 2 shows examples of the coding process from two patients’ clinic notes.

Figure 2.

Examples of the coding process from two patients’ clinic notes. Using a codebook based on the American Association of Diabetes Educators Self-Care Behaviors (AADE7), we identified either sentences or words as a unit of analysis and marked the code IDs on the extracted clinic note sections. The number indicates the code IDs.

2. 7. Frequency Distribution Analysis of DSME/S across AADE7 Principles

To describe occurrence of each of the seven principles among the clinic notes, we first counted the number of the codes for each note and then calculated the mean count of codes for each patient as “codes per visit”. For example, if the code “3.13- Monitor heart health” occurred three times in the patient’s first clinic note and two times in the patient’s second clinic note, we would consider the code “3.13” occurred an average of 2.5 times per visit for this patient. Then, we counted the number of each code across the 200 clinic notes (Table 1). Additionally, we summed the count of codes per visit based on each principle of the AADE7 for each patient. We described the distribution of the counts of codes based on each of the seven principles. We also tried to understand whether the counts of codes were different from one another of the AADE7 principles by conducting pairwise comparisons. We used the Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM)40,41 to test for a statistically significant difference between the means of least squares of the count of codes of each pair of AADE7 principles by two note sections of HPI and I&P. Considering the following factors, we used GLMM40,41 to investigate the differences of the counts of codes: (1) the outcome is the discrete counts, (2) the distribution of the counts of codes is negative binomial, and (3) the counts of codes from seven principles for each patient are repeated measures. We performed GLMM by using PROC GLIMMIX of SAS (Version 9.4 SAS Institute Inc. NC).

2. 8. Assessing Patient-Centeredness in DSME/S

We investigated whether there were differences for count of codes based on patient characteristics for sex (male vs. female), age group (18–64.9 vs. ≥ 65), geographic region (urban vs. rural), type of diabetes (type 1 vs. type 2), history of diagnosis of diabetes (<5 years vs. ≥5 years), hypertension (Yes vs. No), hyperlipidemia (Yes vs. No), coronary artery disease (Yes vs. No), insulin treatment (Yes vs. No), BMI (<30 vs. ≥30),50 and HbA1c (<8% vs. ≥8%).51 To investigate the patient-centeredness in DSME/S, we again used the Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs)40,41 to test for statistically significant differences between the means of least squares across seven principles by patient characteristics. For example, in HPI section, we computed the means of least squares of the count of codes for male and female in the Healthy Eating principle individually. Then we compared the two means of least squares to verify whether there was a statistically significant difference. We performed GLMMs by using PROC GLIMMIX of SAS (Version 9.4 SAS Institute Inc. NC).

3. Results

3.1. Sample Size

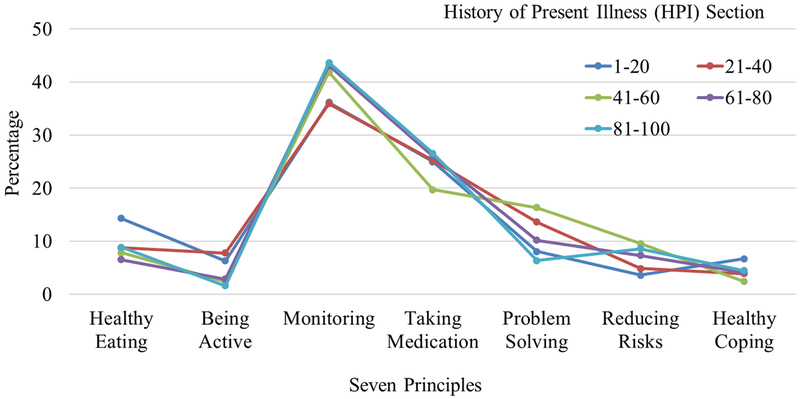

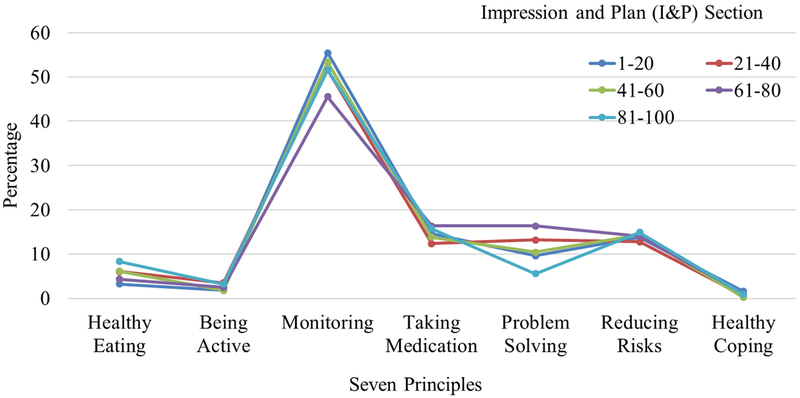

Our dataset included analysis from 200 distinct clinic notes, two notes from each of 100 patients. We calculated the count of codes of each of the seven principles for HPI and I&P sections in sets of 20 patients’ notes (40 clinic notes). We then computed the frequency distribution of each individual principle in the notes. Figure 3 shows the frequency distribution (percentages) of the seven principles for each set of 20 Patients’ notes in HPI section. Figure 4 shows the findings for each set of 20 Patients’ notes in I&P section. We found the frequency distribution of the seven principles did not change significantly in both HPI and I&P sections across each set of 20 patients’ notes. Based on the data saturation theory as applied to the qualitative nature of the study,43 this indicated that adding additional samples into this study beyond the 100 patient dataset would be redundant.

Figure 3.

Frequency distribution of the American Association of Diabetes Educators Self-Care Behaviors (AADE7) Principles for each 20 patients’ notes in History of Present Illness (HPI) Section. For the first 20 patients’ notes, we calculated the count of codes of each of the seven principles in HPI section. Then, the count of codes from one principle was divided by the total counts of codes from the seven principles of the first 20 patients’ notes. We calculated the percentages of seven principles the same way for the other 80 patients’ notes.

Figure 4.

Frequency distribution of the American Association of Diabetes Educators Self-Care Behaviors (AADE7) Principles for each 20 patients’ notes in Impression and Plan (I&P) Section. For the first 20 patients’ notes, we calculated the count of codes of each of the seven principles in I&P section. Then, the count of codes from one principle was divided by the total counts of codes from the seven principles of the first 20 patients’ notes. We calculated the percentages of seven principles the same way for the other 80 patients’ notes.

3.2. Subject Characteristics

Out of 1,317 patients, 100 patients were randomly selected. There were 68 patients aged between 18 to 64.9 years, and 32 patients aged 65 years and older. There were 52 males and 48 females. 37 people lived in urban areas and 63 people lived in rural areas. There were 14 people with type 1 DM and 86 people with type 2 DM. Regarding co-morbid conditions, 61 people had hypertension, 40 had hyperlipidemia, and 9 had documented coronary artery disease. Seventy four people took insulin, 72 people were obese and 47 people had an HbA1c over 8%. The average days for interval between two follow ups was 146 days. Documentation came from 9 providers with 3–56 years of experience managing people with DM. The average of years in practice managing people with DM for the providers is 22 years and standard deviation is 17.79 years, which indicates they have sufficient clinical experience.

3.3. Frequency Distribution Analysis of DSME/S across AADE7 Principles

The information of DSME/S provided by the providers to people with DM was assessed by using deductive thematic analysis and calculating the count of codes per note for each patient among the AADE7 principles. Using the codebook (Table 1) we counted the count of codes across the 100 patients’, 200 clinic notes with 400 note sections. Every clinic note had at least one code. The distribution of counts of codes across the seven principles was not equal. Monitoring (1,808) was addressed most frequently and Healthy Coping (75) were addressed least frequently. We also found the distribution of counts of codes within each principle. Of the total count (3,735), 69% are from 12 codes which were counted more than 100 times. For example, in Monitoring, the codes “3.8- Monitor blood sugar levels” (267), “3.11- Monitor lab test results” (246), “3.13- Monitor heart health” (471), and “3.14- Monitor kidney health” (244) counted more than 200 times, which contributed 68% of the count in Monitoring. Similarly, in Reducing Risks, “6.2- See the doctor regularly” (186) and “6.3- Visit the eye doctor at least once a year” (110) contributed 67% of the count in Reducing Risks.

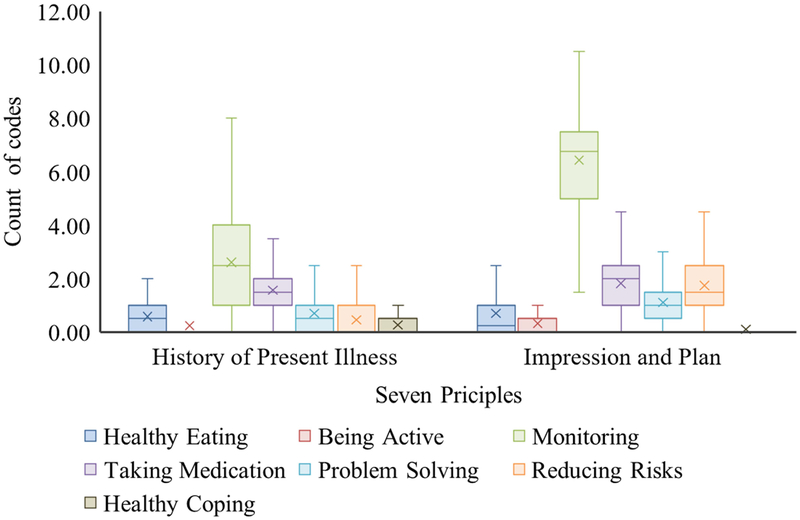

Figure 5 shows the box plots along with descriptive statistics of the count of codes among each of the seven principles by two note sections of HPI and I&P. In HPI section, the order of seven principles by mean of the counts of codes were: Monitoring (mean=2.61, median=2.50, SD=1.97), Taking Medication (mean=1.57, median=1.50, SD=0.96), Problem Solving (mean=0.70, median=0.50, SD=0.75), Healthy Eating (mean=0.59, median=0.50, SD=0.63), Reducing Risks (mean=0.46, median=0, SD=0.65), Healthy Coping (mean=0.27, median=0, SD=0.48), and Being Active (mean=0.25, median=0, SD=0.53). In I&P section, the order of seven principles by mean of the counts of codes were: Monitoring (mean=6.43, median=6.75, SD=2.36), Taking Medication (mean=1.83, median=2.00, SD=1.08), Reducing Risks (mean=1.75, median=1.50, SD=0.93), Problem Solving (mean=1.11, median=1.00, SD=0.92), Healthy Eating (mean=0.70, median=0.25, SD=0.96), Being Active (mean=0.32, median=0, SD=0.58), and Healthy Coping (mean=0.11, median=0, SD=0.33). Considering the mean of the counts of codes per visit, in HPI section, Monitoring has the greatest and Being Active has the smallest count of codes per visit. In I&P section, Monitoring still has the greatest count of codes and Healthy Coping has the smallest count of codes.

Figure 5.

Box plots of count of codes per visit for each of the American Association of Diabetes Educators Self-Care Behaviors (AADE7) Principles. Each box plot includes the upper value within 1.5 times the interquartile range, 75th percentile, 25th percentile, and lower value within 1.5 times the interquartile range. It also includes mean (X) and median (−).

We used GLMM to assess differences between the 21 pairs of means of least-square of counts of codes among the seven principles as shown in Table 2. For example, the mean of least-square of counts of codes of Heathy Eating principle was compared with those of the other six principles. Because multiple comparisons were conducted, we used adjusted p values.52,53 In the HPI section, there was a statistically significant difference of the means of least-square of counts of codes in 16 pairs of principles, with no statistical difference in 5 pairs of principles. In I&P section, there was no statistically significant difference between the means of least-square of counts of codes of 1 pair, and for each of the other 20 pairs of principles, the difference between the means of least-square of counts of codes was statistically significant. Considering both Figure 5 and Table 2, in HPI section, we found Monitoring has the greatest mean of least-square count of codes, and Being Active and Healthy Coping have the smallest means of least-square count of codes. In I&P section, we found Monitoring has the greatest mean of least-square count of codes and Healthy Coping has the smallest mean of least-square count of codes. This indicates that providers delivered less information on Being Active and Healthy Coping compared to Monitoring in HPI section and less information on Healthy Coping compared to Monitoring in I&P section.

Table 2.

Adjusted p values from paired comparison of means of least-square of counts of codes among AADE7 principles in HPI and I&P sections.

| AADE7 Principle | AADE7 Principle | HPI | I&P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Eating | Being Active | <.0001**** | <.0001**** |

| Healthy Eating | Monitoring | <.0001**** | <.0001**** |

| Healthy Eating | Taking Medication | <.0001**** | <.0001**** |

| Healthy Eating | Problem Solving | 0.8862 | 0.0009*** |

| Healthy Eating | Reducing Risks | 0.648 | <.0001**** |

| Healthy Eating | Healthy Coping | 0.0005*** | <.0001**** |

| Being Active | Monitoring | <.0001**** | <.0001**** |

| Being Active | Taking Medication | <.0001**** | <.0001**** |

| Being Active | Problem Solving | <.0001**** | <.0001**** |

| Being Active | Reducing Risks | 0.0282* | <.0001**** |

| Being Active | Healthy Coping | 0.999 | 0.0003*** |

| Monitoring | Taking Medication | 0.0001**** | <.0001**** |

| Monitoring | Problem Solving | <.0001**** | <.0001**** |

| Monitoring | Reducing Risks | <.0001**** | <.0001**** |

| Monitoring | Healthy Coping | <.0001**** | <.0001**** |

| Taking Medication | Problem Solving | <.0001**** | <.0001**** |

| Taking Medication | Reducing Risks | <.0001**** | 0.9976 |

| Taking Medication | Healthy Coping | <.0001**** | <.0001**** |

| Problem Solving | Reducing Risks | 0.0671 | <.0001**** |

| Problem Solving | Healthy Coping | <.0001**** | <.0001**** |

| Reducing Risks | Healthy Coping | 0.1026 | <.0001**** |

Note: Asterisk marks mean the level of significance at **** adjusted p ≤ 0.0001, *** adjusted p ≤ 0.001 and * adjusted p ≤ 0.05. In the HPI section, there was no statistically significant difference of the means of least-square of counts of codes for the following five pairs of principles: Healthy Eating and Problem Solving, Healthy Eating and Reducing Risks, Being Active and Healthy Coping, Problem Solving and Reducing Risks, Reducing Risks and Healthy Coping. In I&P section, there was no statistically significant difference between the means of least-square of counts of codes of Taking Medication and Reducing Risks. For each of the other pair’s principles, the difference between the means of least-square of counts of codes was statistically significant.

Abbreviations: AADE7, American Association of Diabetes Educators Self-Care Behaviors; HPI, History of Present Illness; I&P, Impression and Plan.

3.4. Assessing Patient-Centeredness in DSME/S

We used GLMMs to investigate whether providers deliver patient-centered DSME/S based on patient characteristics across the AADE7 principles by the patient characteristics in (Table 3, Table 4). Table 3 shows that all the adjusted p values in HPI section were greater than 0.05, indicating that there was no statistically significant difference across the AADE seven principles by patient characteristics in the HPI section. For example, for Being Active principle, there was no statistically significant difference of the means of least-square of counts of codes between people with BMI<30 and BMI≥30. We found similar results in sex, age group, geographic region, type of diabetes, history of diagnosis of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, insulin treatment, BMI, and HbA1c across each of the seven principles.

Table 3.

Adjusted p values from comparison of difference between counts of codes across the AADE7 principles by patient characteristics in HPI section.

| Patient Characteristics | Healthy Eating | Being Active | Monitoring | Taking Medication | Problem Solving | Reducing Risks | Healthy Coping |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.9986 | 0.996 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.9997 | 1 |

| Male | |||||||

| Female | |||||||

| Age group | 1 | 0.9753 | 1 | 1 | 0.9997 | 0.9996 | 0.9961 |

| 18–64.9 years | |||||||

| ≥ 65 years | |||||||

| Geographic region | 0.7939 | 0.215 | 1 | 1 | 0.9991 | 1 | 0.7973 |

| Urban | |||||||

| Rural | |||||||

| Type of diabetes | 0.9505 | 0.9982 | 0.9949 | 1 | 0.8086 | 0.9614 | 0.9923 |

| Type 1 | |||||||

| Type 2 | |||||||

| History of diagnosis of diabetes | 1 | 1 | 0.9938 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.8593 |

| < 5 years | |||||||

| ≥ 5 years | |||||||

| Hypertension | 1 | 0.947 | 0.9676 | 1 | 0.9997 | 0.9938 | 1 |

| No | |||||||

| Yes | |||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 | 0.3629 | 1 | 0.9999 | 0.9886 | 0.999 | 1 |

| No | |||||||

| Yes | |||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 1 | 0.9985 | 0.9977 | 0.9914 | 1 | 0.9998 | 0.9946 |

| No | |||||||

| Yes | |||||||

| Insulin treatment | 0.9965 | 0.9965 | 0.843 | 0.8627 | 0.3081 | 0.9322 | 0.9993 |

| No | |||||||

| Yes | |||||||

| BMI | 0.9995 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.9817 |

| < 30 | |||||||

| ≥ 30 | |||||||

| HbA1c | 1 | 1 | 0.9997 | 1 | 0.9996 | 1 | 1 |

| < 8% | |||||||

| ≥ 8% |

Note: All the adjusted p values are greater than 0.05, which means that there was no statistically significant difference between the means of least-square of counts of codes across seven principles by the patient characteristics in HPI section.

Abbreviations: AADE7, American Association of Diabetes Educators Self-Care Behaviors; BMI, body mass index; HPI, History of Present Illness.

Table 4.

Adjusted p values from comparison of difference between counts of codes across the AADE7 principles by patient characteristics in I&P section.

| Patient Characteristics | Healthy Eating | Being Active | Monitoring | Taking Medication | Problem Solving | Reducing Risks | Healthy Coping |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.0414* | 0.246 | 1 | 0.9709 | 1 | 1 | 0.9933 |

| Male | |||||||

| Female | |||||||

| Age group | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.9977 | 1 |

| 18–64.9 years | |||||||

| ≥ 65 years | |||||||

| Geographic region | 0.9995 | 0.9999 | 1 | 1 | 0.9844 | 1 | 0.9358 |

| Urban | |||||||

| Rural | |||||||

| Type of diabetes | 1 | 0.9988 | 1 | 1 | 0.6209 | 1 | 1 |

| Type 1 | |||||||

| Type 2 | |||||||

| History of diagnosis of diabetes | 0.9438 | 0.9623 | 0.9981 | 0.9999 | 0.9973 | 1 | 0.0921 |

| < 5 years | |||||||

| ≥ 5 years | |||||||

| Hypertension | 1 | 1 | 0.9996 | 0.4325 | 1 | 0.9999 | 0.8805 |

| No | |||||||

| Yes | |||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.7451 | 0.9999 | 1 | 0.9997 | 0.8735 | 1 | 0.8459 |

| No | |||||||

| Yes | |||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 0.9051 | 0.8937 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No | |||||||

| Yes | |||||||

| Insulin treatment | 1 | 0.2287 | 1 | 0.4173 | 0.9912 | 0.4039 | 0.1432 |

| No | |||||||

| Yes | |||||||

| BMI | 1 | 0.9984 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.9998 |

| <30 | |||||||

| ≥ 30 | |||||||

| HbA1c | 0.9979 | 0.9344 | 0.9995 | 0.9996 | 0.9841 | 0.9993 | 1 |

| <8% | |||||||

| ≥ 8% |

Note: Asterisk mark means the level of significance at * adjusted p ≤ 0.05. Most adjusted p values in I&P section are greater than 0.05, which means that there was no statistically significant difference between the means of least-square of counts of codes across seven principles by the patient characteristics in I&P section. Only the adjusted p value of comparison of the means of least-square of counts of codes between male and female for Healthy Eating principle is smaller than 0.05, which is equal to 0.0414.

Abbreviations: AADE7, American Association of Diabetes Educators Self-Care Behaviors; BMI, body mass index; I&P, Impression and Plan.

Similarly, Table 4 shows that most adjusted p values in I&P section were greater than 0.05, showing that there was no statistically significant difference between the means of least-square of counts of codes across seven principles by the patient characteristics in I&P section. We found that only the adjusted p value between male and female for the Healthy Eating principle was statistically significant (adjusted p value=0.0414). The mean of least-square of count of Healthy Eating codes in male was 0.6583 unit higher than female, which means providers delivered more information of the Healthy Eating principle to men compared to women in I&P section. In general, the statistical results show that providers delivered DSME/S similarly regardless of patient characteristics.

4. Discussion

Ongoing DSME/S is a vital component for the management of people with DM.2 The diabetes education that providers deliver during follow up clinic visits may be the only source for DSME/S for many people with diabetes. In this study, we investigated the frequency distribution of information providers delivered to people with DM during follow up visits based on the AADE7 guidelines and whether they delivered patient-centered DSME/S based on patient characteristics by using GLMMs.

Compared with prior studies of clinic notes of people with DM31–35 that employed natural language processing techniques, our study adopted manual coding for the clinic notes and conducted regular group reviews. We believe this strategy allowed for the accuracy of coding to be unaffected by complicated sentences, incomplete sentences, acronyms and abbreviations used by healthcare providers (Figure 2). From a practical perspective, manual coding is more efficient for 200 clinic notes and with higher accuracy when comparing to natural language processing in this pilot study. In many clinic notes, use of EHR templates may result in certain types of documentation becoming more prevalent as an artifact based on construction of the template. This study focused on HPI and I&P sections, which are less likely to be affected by this artifact. In most clinic notes, the providers have to actively document in these two sections, which is more likely to reflect actual clinic interactions.

This study shows the frequency distribution of the AADE7 principles on clinic notes from follow up clinic visits. Interestingly, Monitoring appeared to be the most common in both HPI and I&P sections. Being Active was the least common principle in HPI section and Healthy Coping was the least common one in I&P section. Monitoring helps the patient to track and confirm whether blood glucose levels are within target goals.54 One of the reasons for providers to focus more on Monitoring may be due to insurance requirements. For example, current Medicare coverage requires that providers should document information about blood glucose data, monitoring frequency and HbA1c to have glucose testing equipment and supplies covered for the recipients.55 Another reason may be that most patients in this group from a tertiary care center were on insulin, and regular monitoring is needed for appropriate dosing of insulin. Lack of adequate time may be one of the reasons for providers not addressing other principles such as Being Active and Healthy Coping, so Monitoring and Taking Medications become their first option. It is also possible that providers discussed Being Active and Healthy Coping, but due to time constraints, or technological factors, they may not include the discussion in documentation. Additionally, providers may have provided more comprehensive and customized information at an initial visit and may not feel the need to repeat the same information in the follow up visits. However, the guidelines indicate that it is important to deliver DSME/S at diagnosis, at an annual assessment of education, when new complicating factors occur, and at any transition in care.6,7 It may also be difficult to motivate people with DM to be active because of factors like increased fatigue, which is common in patients with DM,56–59 chronic comorbid condition, and social and financial limitations.46

The Being Active principle can help people with DM lower blood sugar, lower cholesterol, improve blood pressure, lower stress and anxiety, and improve mood.60 The Healthy Coping principle provides different ways for people with DM to deal with emotional problems, such as stress, depression and anxiety related to diabetes.61,62 People with DM go through a great deal of social and financial adjustments causing undue stress in day-to-day life.46 Stress can impair a person’s ability to exercise, check blood glucose regularly or eat healthy foods.63 This may affect their ability to improve self-management behaviors such as regular exercise, healthy eating or checking blood glucose.64–66 Healthy Coping skills can help patients to overcome these hurdles.67–71 Therefore, these two principles deserve more attention by both providers and people with DM.

Diabetes is a chronic disease, requiring patient-centered care focusing on personal, medical and social factors. We found there were almost no differences between the counts of codes across patient characteristics by the AADE7 principles in HPI and I&P section. The results may indicate that providers deliver standardized DSME/S in follow up clinic visits. However, our findings may indicate a lack of patient-centered education when people with DM visit providers, suggesting that providers may not be addressing important patient characteristics. This was applicable to sex, age group, geographic region, type of diabetes, history of diagnosis of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, insulin treatment, BMI, and HbA1c. This lack of patient-centered education in follow up visits may be multifactorial, including time limitations during clinic visit, focus on documentation of the visit, lack of knowledge about most recent guidelines and cultural sensitivity of the provider.72 There were no differences in patient characteristics for frequency of the AADE7 principles, but it is also possible that there are differences for frequency at subcategory level of the AADE7 principles by patient characteristics. In the future study, we will compare the differences for frequency at subcategory level.

Patient-centered approach to diabetes requires communication and information sharing between patients and providers. To assess involvement of people with DM in DSME/S, we also collected information regarding blood glucose data sharing. In this study, most people with DM (88%) shared their glucose data with providers, suggesting their active involvement in Monitoring. We also studied whether there were differences between sex (male vs. female) and age groups (18–64.9 vs. ≥ 65) with preference of sharing glucose data. There was no statistically significant difference between sex and preference of sharing glucose data (p=0.640, Pearson’s chi-squared test73). There was no difference between age groups of preference of sharing glucose data (p=0.747, Fisher’s exact test74). Patients can benefit from sharing glucose data with physicians, which increases patient engagement.75 Ayuk and Johnson conducted research about remotely monitoring glucose data from people with type 2 DM for 90 days for benefits evaluation of remote glucose monitoring and found an increase in frequency of testing blood glucose by 44% at the end of study period.75 Sharing information also helps providers to have a better understanding of blood glucose trends in order to tailor medical therapy.75,76 One method of information sharing in the current era of electronic health records is secure access to medical records. At UMHC, HEALTHConnect,77 a patient portal allows access to laboratory tests and clinic notes to the patient and also allows email communication directly with the provider. In this study, out of 100 people with DM, 51 people had an active account. This shows that half of the patients could review their clinic notes and potentially get DM education if it is included in the note.

Limitations of the Study

Our study has some limitations. First, the study was conducted in the US and may not apply to health care settings in other countries. We only collected data from a tertiary referral center (CIDEC) at an academic center (UMHC) that employs a single EHR. Future data analysis should involve clinic notes from multiple institutions to improve external validity. However, the sample size in this pilot study, which was 200 clinic notes from 100 patients, was deemed adequate to identify gaps in the information providers deliver to people with DM during clinic visits based on the AADE7 guidelines. We used the AADE7 guidelines in our study. We believe AADE7 guidelines provide equivalent and comprehensive key elements of DSME/S, such as nutrition therapy, physical activity, smoking cessation, psychosocial issues, glycemic management, and pharmacologic therapy.78 However, we recognize there are other diabetes guidelines such as, “Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes” from ADA78, in the US, and internationally which include excellent recommendations for diabetes self-management. Another limitation may be the influence of difference in levels of expertise for diabetes practice among providers in documentation pattern. The years of practice for the providers in this study managing people with DM ranges from 3 to 56 years. The average of years in practice managing people with DM for the providers is 22 years and standard deviation is 17.79 years, which indicates they have sufficient clinical and EHR experience. Additionally, clinical encounter includes face-to-face conversations and education which may not be completely reflected in a written note. In this study, two experienced endocrinologists (Khan and Patel) verified the interpretation of abridged contents in clinic notes. Lastly, in this pilot study, we had more people with DM type 2 than DM type 1. We did not segregate DM type 1 and DM type 2 into separate groups. Since these two groups have significant differences in long-term management, future focused studies are needed in this area.

5. Conclusions

This study of clinic notes investigated the frequency distribution of DSME/S providers delivered to the people with DM during follow up clinic visits in the US based on the AADE7 principles. It found that providers focused on Monitoring blood glucose in most notes but may not have addressed important principles like Being Active and Healthy Coping adequately. This approach by providers may have long-term implications particularly in the presence of multiple comorbid conditions in people with DM. Generally, we found no difference in DSME/S in the clinic notes based on patient characteristics including sex, demography and comorbid conditions. This may indicate a lack of patient-centered education when people with DM visit providers. With the increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus both globally, and in the US, further studies are needed to identify the underlying reasons why providers have difficulty delivering ongoing patient-centered education even in a specialty setting and identify whether a separate referral to a diabetes educator was part of follow up visits. Research involving providers, as well as people with diabetes, is needed to enhance the accuracy of the clinic note. Future studies should focus not only on documentation, but also on the clinic note as a source of individualized DSME/S for people with DM type 1 or DM type 2 who choose to access their clinic notes electronically.

What’s known

Diabetes self-management education and support help to improve glycemic control and reduce risks for complications for people with diabetes.

What’s new

An analysis of clinic notes from follow up clinic visits focused on diabetes management mostly provided information on Monitoring. Health care providers delivered diabetes education to people with diabetes regardless of their characteristics including type of diabetes, gender and age. This may indicate a lack of patient-centered education when people with diabetes visit providers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Terri Benskin for providing support for searching correct ICD-10 codes when we identified eligible patients. The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders (NIDDK) P30DK092950 from Center for Diabetes Translation Research (CDTR) Pilot & Feasibility (P&F) program grant was available when this project was conducted.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Reference

- 1.National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(7):1159–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haas L, Maryniuk M, Beck J, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education and support. The Diabetes Educator. 2012;38(5):619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(3):561–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolucci A, Cavaliere D, Scorpiglione N, et al. A comprehensive assessment of the avoidability of long-term complications of diabetes. A case-control study. SID-AMD Italian Study Group for the Implementation of the St. Vincent Declaration. Diabetes Care. 1996;19(9):927–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Four Critical Times to See Your Diabetes Educator. The American Association of Diabetes Educators. https://www.diabeteseducator.org/news/aade-blog/aade-blog-details/press-releases/2016/11/15/four-critical-times-to-see-your-diabetes-educator. Published 2016. Accessed March 31, 2019.

- 7.Powers MA, Bardsley J, Cypress M, et al. Diabetes Self-management Education and Support in Type 2 Diabetes: A Joint Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association, the American Association of Diabetes Educators, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Diabetes Care. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strawbridge LM, Lloyd JT, Meadow A, Riley GF, Howell BL. Use of Medicare’s Diabetes Self-Management Training Benefit. Health Education & Behavior. 2015;42(4):530–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li R, Shrestha SS, Lipman R, Burrows NR, Kolb LE, Rutledge S. Diabetes self-management education and training among privately insured persons with newly diagnosed diabetes--United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63(46):1045–1049. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Funnell MM, Siminerio LM. Access to diabetes self-management education. The Diabetes Educator. 2009;35(2):246–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caceres V How a Certified Diabetes Educator Can Enhance Your Diabetes Care. https://health.usnews.com/health-care/patient-advice/articles/2017-07-27/how-a-certified-diabetes-educator-can-enhance-your-diabetes-care. Published 2017. Accessed October 19, 2018.

- 12.Diabetes Self-Management Education Barrier Study. Maine Department of Health and Human Services 2006.

- 13.Dugdale DC, Epstein R, Pantilat SZ. Time and the Patient–Physician Relationship. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14(S1):34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radecki SE, Kane RL, Solomon DH, Mendenhall RC, Beck JC. Do Physicians Spend Less Time with Older Patients? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1988;36(8):713–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gottschalk A, Flocke SA. Time spent in face-to-face patient care and work outside the examination room. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(6):488–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Statista. Amount of time U.S. primary care physicians spent with each patient as of 2018. https://www.statista.com/statistics/250219/us-physicians-opinion-about-their-compensation/. Published 2018. Accessed October 5, 2018.

- 17.Joukes E, Abu-Hanna A, Cornet R, de Keizer NF. Time Spent on Dedicated Patient Care and Documentation Tasks Before and After the Introduction of a Structured and Standardized Electronic Health Record. Applied Clinical Informatics. 2018;9(1):46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corbett J 6 Questions Your Doctor Should be Asking You. https://www.everydayhealth.com/columns/health-answers/questions-your-doctor-should-be-asking-you/. Published 2015. Accessed November 12, 2018.

- 19.Williams GC, Zeldman A. Patient-centered diabetes self-management education. Current Diabetes Reports. 2002;2(2):145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siddharthan T, Rabin T, Canavan ME, et al. Implementation of Patient-Centered Education for Chronic-Disease Management in Uganda: An Effectiveness Study. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166411–e0166411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kent D, D’Eramo Melkus G, Stuart PM, et al. Reducing the risks of diabetes complications through diabetes self-management education and support. Population Health Management. 2013;16(2):74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pieber TR, Brunner GA, Schnedl WJ, Schattenberg S, Kaufmann P, Krejs GJ. Evaluation of a structured outpatient group education program for intensive insulin therapy. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(5):625–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stellefson M, Dipnarine K, Stopka C. The chronic care model and diabetes management in US primary care settings: a systematic review. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2013;10:E26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deakin TA, Cade JE, Williams R, Greenwood DC. Structured patient education: the diabetes X-PERT Programme makes a difference. Diabetic Medicine. 2006;23(9):944–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korsatko S, Habacher W, Rakovac I, et al. Evaluation of a teaching and treatment program in over 4,000 type 2 diabetic patients after introduction of reimbursement policy for physicians. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1584–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.AADE. About AADE. https://www.diabeteseducator.org/about-aade. Accessed Oct 15, 2018.

- 27.Boren SA. AADE7™ Self-care Behaviors: systematic reviews. The Diabetes Educator. 2007;33(6):866, 871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.AADE. AADE7 Self-Care Behaviors™. https://www.diabeteseducator.org/patient-resources/aade7-self-care-behaviors. Published 2017. Accessed September 10, 2017.

- 29.AADE 7 Self Care Behaviors. American Diabetes Educators Association. https://www.diabeteseducator.org/docs/default-source/legacy-docs/_resources/pdf/publications/aade7_position_statement_final.pdf?sfvrsn=4. Published 2014. Accessed September 10, 2017.

- 30.American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Diabetes M. Guidelines Abstracted from the American Geriatrics Society Guidelines for Improving the Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: 2013 Update. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61(11):2020–2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei WQ, Tao C, Jiang G, Chute CG. A high throughput semantic concept frequency based approach for patient identification: a case study using type 2 diabetes mellitus clinical notes. AMIA Annual Symposium proceedings AMIA Symposium. 2010;2010:857–861. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nunes AP, Yang J, Radican L, et al. Assessing occurrence of hypoglycemia and its severity from electronic health records of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2016;121:192–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng L, Wang Y, Hao S, et al. Web-based Real-Time Case Finding for the Population Health Management of Patients With Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Validation of the Natural Language Processing-Based Algorithm With Statewide Electronic Medical Records. JMIR Medical Informatics. 2016;4(4):e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pakhomov S, Shah N, Hanson P, Balasubramaniam S, Smith SA. Automatic quality of life prediction using electronic medical records. AMIA Annual Symposium proceedings AMIA Symposium. 2008:545–549. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu S, Wang L, Ihrke D, et al. Correlating Lab Test Results in Clinical Notes with Structured Lab Data: A Case Study in HbA1c and Glucose. AMIA Joint Summits on Translational Science proceedings AMIA Joint Summits on Translational Science. 2017;2017:221–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.What Is the Role of Natural Language Processing in Healthcare? https://healthitanalytics.com/features/what-is-the-role-of-natural-language-processing-in-healthcare. Published 2016. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- 37.Maddox TM, Matheny MA. Natural Language Processing and the Promise of Big Data: Small Step Forward, but Many Miles to Go. Circulation Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2015;8(5):463–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson J Outpatient Clinics: Keys For Successful Participation. UCSD School of Medicine. https://meded.ucsd.edu/clinicalmed/clinic.htm. Accessed October 15, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker J, Leveille S, Bell S, et al. OpenNotes After 7 Years: Patient Experiences With Ongoing Access to Their Clinicians’ Outpatient Visit Notes. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2019;21(5):e13876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCulloch CE, Neuhaus JM. Generalized linear mixed models. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. 2005;4. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Breslow NE, Clayton DG. Approximate Inference in Generalized Linear Mixed Models. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1993;88(421):9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tyukin B Healthcare Analytics with Cerner: Part 1 - Data Acquisition. https://boristyukin.com/healthcare-analytics-with-cerner-part-1-data-acquisition/. Published 2016. Accessed October 10, 2018.

- 43.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity. 2018;52(4):1893–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye Q, Khan U, Boren SA, Simoes EJ, Kim MS. An Analysis of Diabetes Mobile Applications Features Compared to AADE7™: Addressing Self-Management Behaviors in People With Diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2018;12(4):808–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ye Q, Boren SA, Khan U, Kim MS. Evaluation of Functionality and Usability on Diabetes Mobile Applications: A Systematic Literature Review. Paper presented at: International Conference on Digital Human Modeling and Applications in Health, Safety, Ergonomics and Risk Management 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye Q, Boren SA, Khan U, Simoes EJ, Kim MS. Experience of diabetes self-management with mobile applications: a focus group study among older people with diabetes. European Journal for Person Centered Healthcare. 2018;6(2):262–273. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Creswell JW. Educational research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calculate Your Body Mass Index. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/lose_wt/BMI/bmicalc.htm. Accessed May 1, 2019.

- 51.Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Supplement 1):S61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cai W Making Comparisons Fair: How LS-Means Unify the Analysis of Linear Models. SAS Institute Inc.;2014. [Google Scholar]

- 53.SAS. SAS/STAT(R) 9.2 User’s Guide, Second Edition https://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/statug/63033/HTML/default/viewer.htm#statug_glimmix_sect006.htm. Accessed May 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 54.AADE. Monitoring. https://www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/aade7-self-care-behaviors/aade7-self-care-behaviors-monitoring. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 55.Current Medicare Coverage of Diabetes Supplies. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/Downloads/SE18011.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed May 24, 2019.

- 56.Fritschi C, Quinn L. Fatigue in patients with diabetes: a review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2010;69(1):33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hll-Briggs F, Cooper DC, Loman K, Brancati FL, Cooper LA. A qualitative study of problem solving and diabetes control in type 2 diabetes self-management. The Diabetes Educator. 2003;29(6):1018–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koch T, Kralik D, Sonnack D. Women living with type II diabetes: the intrusion of illness. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 1999;8(6):712–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wenzel J, Utz SW, Steeves R, Hinton I, Jones RA. Plenty of sickness. The Diabetes Educator. 2005;31(1):98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.AADE. Being Active. https://www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/aade7-self-care-behaviors/being-active. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 61.Fisher EB, Thorpe CT, Devellis BM, Devellis RF. Healthy coping, negative emotions, and diabetes management: a systematic review and appraisal. The Diabetes Educator. 2007;33(6):1080–1103; discussion 1104–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.AADE. Healthy Coping. https://www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/aade7-self-care-behaviors/healthy-coping. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 63.Depression. American Diabetes Association. http://www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/complications/mental-health/depression.html. Published 2014. Accessed March 16, 2018.

- 64.Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, et al. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fisher L, Mullan JT, Arean P, Glasgow RE, Hessler D, Masharani U. Diabetes distress but not clinical depression or depressive symptoms is associated with glycemic control in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Diabetes Care. 2010;33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(21):3278–3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Yardley JE, et al. Physical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(11):2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bohm A, Weigert C, Staiger H, Haring HU. Exercise and diabetes: relevance and causes for response variability. Endocrine. 2016;51(3):390–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Faulkner MS, Michaliszyn SF, Hepworth JT, Wheeler MD. Personalized exercise for adolescents with diabetes or obesity. Biological Research for Nursing. 2014;16(1):46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang XL, Pan JH, Chen D, Chen J, Chen F, Hu TT. Efficacy of lifestyle interventions in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2016;27:37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2017 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clinical Diabetes: a publication of the American Diabetes Association. 2017;35(1):5–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Powell PW, Corathers SD, Raymond J, Streisand R. New approaches to providing individualized diabetes care in the 21st century. Current Diabetes Reviews. 2015;11(4):222–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Greenwood PE, Nikulin MS. A guide to chi-squared testing. Vol 280: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Camilli G, Hopkins KD. Applicability of chi-square to 2× 2 contingency tables with small expected cell frequencies. Psychological Bulletin. 1978;85(1):163. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ayuk Vivian N., Johnson A Patients, physicians benefit from remote blood glucose monitoring. https://www.healio.com/endocrinology/diabetes-education/news/online/%7Bf2e0cfb6-db18-428c-a7ee-586516149047%7D/patients-physicians-benefit-from-remote-blood-glucose-monitoring. Published 2018. Accessed November 12, 2018.

- 76.Cohen DJ, Keller SR, Hayes GR, Dorr DA, Ash JS, Sittig DF. Integrating Patient-Generated Health Data Into Clinical Care Settings or Clinical Decision-Making: Lessons Learned From Project HealthDesign. JMIR Human Factors. 2016;3(2):e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Your MU Health Care. https://www.muhealth.org/patient-login. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- 78.Introduction: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Supplement 1):S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]