Abstract

Fournier gangrene (FG) is a genitourinary necrotizing fasciitis that can be lethal if not promptly diagnosed and surgically debrided. The diagnosis is often made by physical examination paired with an appropriate clinical suspicion and supporting laboratory values. Imaging, particularly CT, plays a role in delineating involved fascial planes for operative debridement and occasionally in diagnosing FG. Less commonly, the imaging manifestations of FG may also be seen on ultrasound, radiographs, and MRI. With the ubiquitous use and availability of CT, radiologists have a growing role in recognizing FG. This can be challenging in the absence of fascial gas, but a CT scoring system for necrotizing fasciitis can be helpful in making the diagnosis. Recent series suggest that this predominantly male disease has a rising incidence in women. Women with FG are more likely to be morbidly obese and have vulvar or labial involvement compared to men. Imaging mimics include ulcerative and necrotic tumors, traumatic or iatrogenic fascial gas, and vaginitis emphysematosa. The purpose of this pictorial review is to illustrate the imaging manifestations of FG and its mimics, with emphases on necrotizing fasciitis CT scoring systems and FG in women.

Keywords: Fournier gangrene, necrotizing fasciitis, CT, acute care surgery, emergency radiology, genitourinary radiology

Introduction

Fournier gangrene (FG) is a genitourinary necrotizing fasciitis that can be lethal if not promptly diagnosed and surgically debrided. While the diagnosis is often be made by physical examination and clinical presentation, imaging has a growing role in diagnosing and determining extent of FG. CT is the most common modality used to evaluate FG. On imaging, the hallmark of FG and necrotizing fasciitis is soft tissue or fascial gas with or without surrounding soft tissue inflammatory change (e.g., stranding, fluid tracking, and other surrogates of inflammatory change) with the appropriate clinical suspicion for a septic process. Although the absence of soft tissue gas does not exclude FG, it is much more likely to manifest with air compared with necrotizing fasciitis at other anatomic sites (predominantly in the extremities) [1–3]. As this diagnosis can be challenging in the absence of soft tissue gas, a CT scoring system for necrotizing fasciitis has been developed [1, 3]. The purpose of this pictorial review is to illustrate the imaging manifestations of FG and its mimics, with emphases on necrotizing fasciitis CT scoring systems and FG in women.

Definition and patient characteristics

The most commonly cited and accepted definition of FG is a necrotizing fasciitis of the perineal, genital, and/or perianal regions, which will serve as the definition for this review. Manifestations in these three anatomic areas are demonstrated in Figure 1. This was proposed by Smith et al. [4] and reiterated by the most cited FG study in the literature (according to Google Scholar), by Eke [5]. Although the infectious sources are often idiopathic, common identifiable sources of infection include the skin (e.g., necrotic ulcers), urinary tract (e.g., fulminant urinary tract infection with urethral stricture), and gastrointestinal sites (e.g., perforated colorectal cancer or diverticulitis) [5]. On imaging of FG, bilateral distribution occurs in about 60% and involvement of >2 fascial compartments occur in approximately 70% [1]. Organized abscesses occur in about 20% to 50% of patients [1, 2].

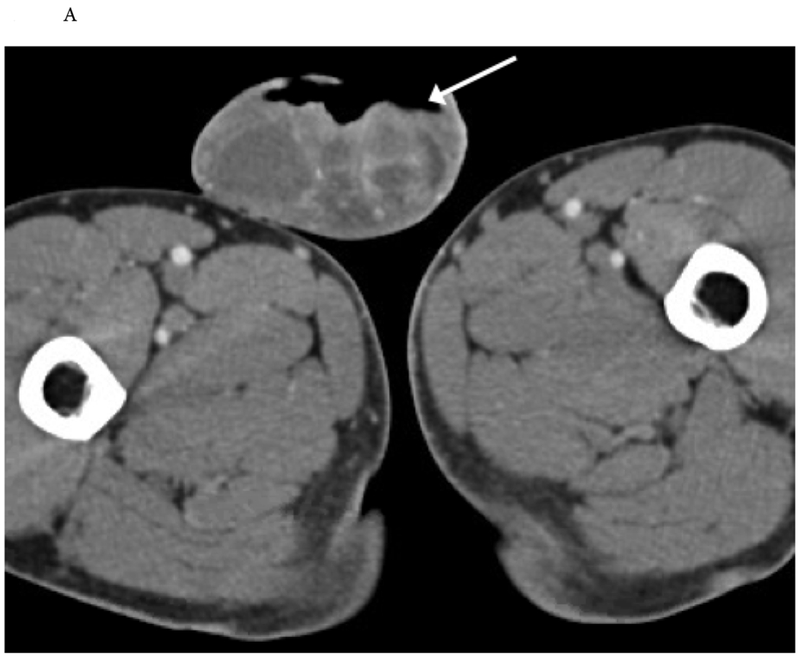

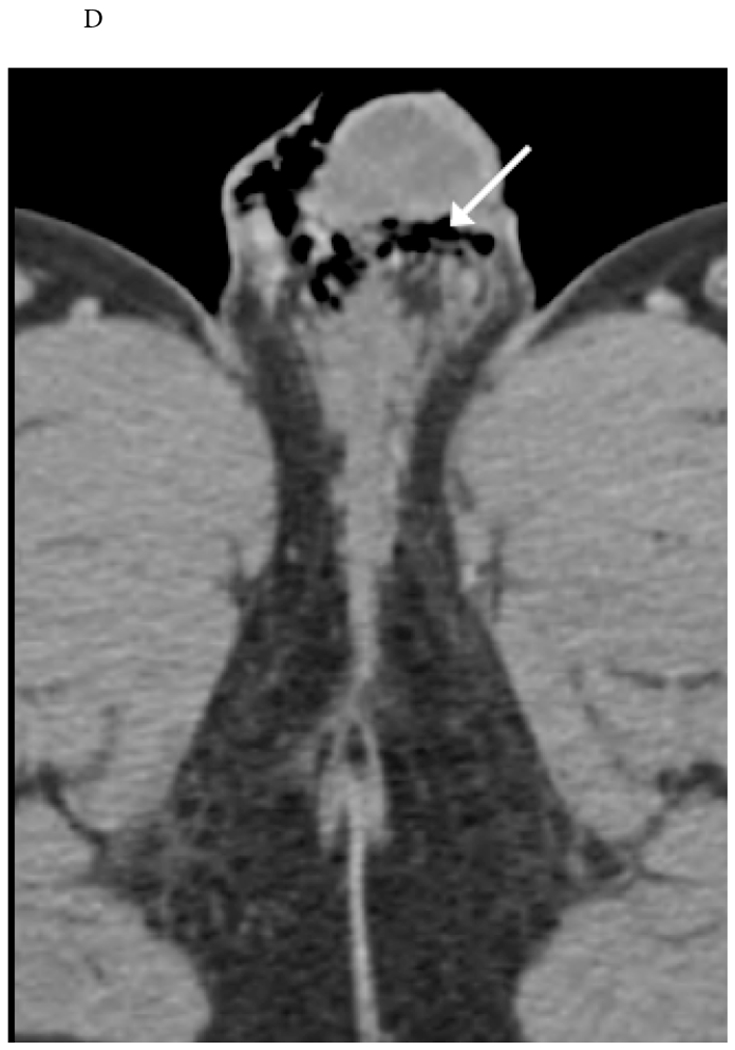

Figure 1.

Surgically-proven Fournier gangrene (FG) in six different patients, including three men (A-C) and three women (D-F) demonstrated in unenhanced (A) and contrast enhanced (B-F) axial CT images. The three areas of anatomic involvement to satisfy the definition of FG as a necrotizing fasciitis centered in or involving the genitals (G; illustrated in A and B), perineum (P; illustrated in B and E), and ischiorectal fossa (IR; illustrated in C and F) are illustrated in both men (A-C) and women (D-F). Women with FG are often more obese compared to their male counterparts, which is illustrated in the three female patients (D-F), each of whom had a BMI >55.

Although Fournier gangrene is historically a heavily male predominant disease, with women accounting for 4% to 10% of cases [5, 6], the reported incidence of FG in women is increasing in modern series. In two modern series, the proportion of women in retrospective cohorts ranges from 21% to 55% of patients [1, 7]. Although FG is often heavily associated with diabetes mellitus, the proportion of patients with diabetes in the largest review of FG patients (1,726 patients) was 20% [5]. However, the incidence of diabetes in a more modern series where the mean body mass index (BMI) was 42 was 58% [1]. That series also found women to have a significantly higher BMI compared to their male counterparts. [1]. CT case examples of FG in women are shown in Figure 1D, 1E, 1F and Figure 2 (also in 3 of the 5 panels of the subsequently referenced Figure 10).

Figure 2.

89-year-old woman with labial Fournier gangrene. Contrast enhanced axial CT image demonstrates extensive soft tissue thickening, inflammatory stranding, and a large volume of gas (dashed arrows) tracking from the left labia majora and extending anteriorly along the mons pubis and posteriorly along the ischiorectal fossa, compatible with Fournier gangrene, which was confirmed at debridement.

Figure 10.

Fournier gangrene without fascial gas. 55-year-old man with 2 days of perineal pain and scrotal swelling with fever and leukocytosis. CT demonstrates extensive soft tissue stranding and edema in penis, scrotum, perineum, lower anterior abdominal wall, and proximal right thigh (arrows, A-B). Although no free fascial air was present, this was concerning for Fournier gangrene, which was confirmed at surgery.

Most men and women with FG will have both genital and perineal involvement. However, women will almost always have vulvar or labial involvement (95% - 100%) (Figure 2) whereas men are more likely to have scrotal involvement (71% - 76%) than involvement of the penis (47% - 53%). Otherwise, the anatomic distribution between FG in men and women is similar with perineal involvement in 84% - 87% and perianal involvement in 26% - 32% [1].

Relevant anatomy and rationale for imaging

Fascial male anatomy is shown in Figure 3 and the three main areas of anatomic involvement in men and women are illustrated in Figure 1. Although naming specific fascial planes may or may not be helpful for the surgeon’s operative planning, radiologists should aim to detail the extent of the fascial air (if present) and soft tissue inflammation when interpreting FG cases. Identifying extraperitoneal spread along the space of Retzius and intraperitoneal extension is particularly important, as most operations for FG without associated processes (e.g., perforated colon cancer) do not require a laparotomy [1]. A case illustrating fascial spread is shown in Figure 4. Urgent to emergent surgical debridement is required for treatment of FG to adequately excise all the affected tissue. Most patients will require multiple debridements. Systemic antibiotics, resuscitation, and critical care management are also typically employed in the care of FG patients [5, 7].

Figure 3.

Normal pelvic fascial anatomy. 61-year-old man with a normal MR of the pelvis. T2-weighted high-resolution sagittal sequence demonstrates normal fascial anatomy.

Figure 4.

Demonstration of necrotizing fasciitis spread through fascial planes in a 64-year-old man who initially presented with scrotal swelling. Unenhanced axial (A) and sagittal (B) CT images demonstrate fascial air (dotted white arrows) in the right scrotum and buttock (A) and demonstrating spread cranially through the space of Retzius (large arrow in B). The patient underwent perineal and scrotal debridement, along with laparotomy which demonstrated fascial necrosis.

Many FG surgical series state that imaging was used selectively, but do not give specific metrics that reflect this [8–10]. The role of imaging is not well defined in the patients with FG status post debridement but the general principle is to assess for signs of necrotizing fasciitis beyond the operative bed, not accounted for by the surgical defect. While CT is the modality of choice for evaluation of FG due to its rapid image acquisition and availability, the role of radiography, ultrasound, and MR are also discussed here.

Conventional radiography

Pelvic radiographs are generally a poor choice to image clinically suspected FG. A meta-analysis encompassing 23 studies with 5,982 patients found radiographs had a sensitivity of 49% for necrotizing fasciitis at any anatomic site compared to a CT sensitivity for necrotizing fasciitis of 93%. [11]. In addition, overlapping gas within the hollow viscera of the pelvis may cause a false positive result. When radiographs are obtained, fascial gas may be apparent in the scrotum (Figure 5), labia, or perineum and may be better demonstrated on lateral or oblique views.

Figure 5.

17-year-old paraplegic male with fever and right thigh erythema and swelling. (A) Pelvic radiograph and (B) scrotal ultrasound in a man with perineal swelling and pain demonstrating soft tissue gas and edema in scrotum and the proximal right thigh (dotted arrow). Echogenic foci of gas (dotted arrow) with ring down artifact (short arrows) and dirty shadowing (long arrow) are seen on the ultrasound.

Ultrasound

Ultrasonography (US) is frequently used as the first modality for imaging the penis and scrotum [12]. US can evaluate for subcutaneous emphysema, inflammation and the presence of a fluid collection especially when CT is not immediately available. Doppler US can evaluate for scrotal and perineal hyperemia. Furthermore, US is useful in cases with an unclear diagnosis and possibility of alternative diagnosis such as an incarcerated inguinoscrotal hernia, testicular torsion or orchitis. In incarcerated inguinoscrotal hernia, gas is present within the scrotum (like FG); however, it is confined within the bowel lumen. US limitations include its relatively small field of view, operator dependence, and occasional procedure intolerance by patients given need for direct pressure on the perineum during the examination [12, 13].

On US, FG appears as a thickened, edematous scrotal wall and perineum with hyperechoic, hyperreflecting foci representing gas within the wall which demonstrate ring down artifact and “dirty” acoustic shadowing [14, 15] (Figures 5 and 6). The testes most often appear normal because of their independent blood supply which is not affected by the compromised facial and cutaneous circulation of the scrotum [16]. Doppler US demonstrates hyperemia and dilated scrotal vessels which are not seen on normal examinations [17]. Two small sonographic cohorts of FG have been reported including a series of 6 patients with US performed by emergency physicians [18] and another with 3 patients [19]. In all 9 of these patients in the two small series, all patients had sonographic manifestations of soft tissue gas.

Figure 6.

73-year-old man with prostate cancer with metastases to the bladder presents with penile and scrotal swelling, evident on physical exam. (A) Penile ultrasound demonstrates superficial hyperechogenic foci (solid arrow) with dirty posterior shadowing (dashed arrow). (B) Unenhanced CT of the pelvis confirms fascial gas (dotted arrow) with associated inflammation. Fournier gangrene was confirmed at surgery, which included debridement of lower abdominal wall, perineum and scrotum.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to evaluate soft tissue and define the extent of inflammatory or infectious diseases. As MRI has become more readily available, it is increasingly used as a problem-solving resource when US or CT findings are equivocal or suboptimal to make a definitive diagnosis. The large FOV and multiplanar capability of MR imaging allow for better delineation of the extent of disease and in some cases can identify unexpected sources of infection which may aid in planning surgical debridement or percutaneous drainage. Due to the long acquisition time of MRI and potential lack of added value over CT, MRI should not be the primary imaging modality in patients with suspected FG.

However, MR imaging may occasionally be used in cases with unclear findings or when other differential diagnoses are being considered or FG may be encountered incidentally on MRI. Some have advocated using MRI to assess for residual FG in patients following debridement [21]. Overall, the authors do not recommend use of MRI for clinically suspected FG when CT is readily available. MRI of FG in the literature is comprised of only case reports [21–23]. On MRI FG appears as extensive perineal inflammation, fascial thickening, and soft-tissue gas with or without fluid collections or fistulas. Soft-tissue gas on MR imaging appears as regions of signal void and susceptibility artifact. Inflammation is identified by increased T2 signal of the perineal fat on fat suppressed images. Figures 7 and 8 illustrate MR manifestations of FG in two patients.

Figure 7.

69-year-old-man with surgically proven Fournier gangrene, imaged with MRI prior to debridement. T2 fat saturated MRI (A and B) demonstrate diffuse edema of the perineum and scrotum (long arrows) with air-fluid level seen in the right perineum (short arrow).

Figure 8.

63-year-old-man with preoperative MR imaging of surgically proven Fournier gangrene. Contrast enhanced T1 images (A and B) demonstrate gas within the scrotum and scrotal wall (A) and perineal abscess (B).

CT

Computed tomography is the modality of choice for evaluation of FG with high sensitivity, specificity, and delineation of involved fascial planes. CT can be useful for preoperative planning for determining the extent of fascial involvement and diagnosing unclear cases. Although evaluating the extent of soft tissue gas on CT does not require intravenous contrast, contrast-enhanced CT may provide additional diagnostic information, particularly when evaluating for abscesses (Figure 9). Intravenous contrast may also provide useful information about the bowel wall when a colorectal source of FG is suspected and help determine the need for laparotomy in addition to soft tissue debridement. The most common CT findings are fascial air, muscle or fascial edema, and subcutaneous edema [1, 3]. A CT scoring system has been described for necrotizing fasciitis in a cohort of 44 patients [3] and subsequently validated in a retrospective cohort of 38 patients with FG [1].

Figure 9.

Fournier gangrene with abscess and no fascial gas. 49-year-old man with a left ischiorectal fossa mass initially interpreted as a soft tissue tumor (dotted arrow, A) on a non-contrast CT. Follow-up contrast enhanced CT showed an extensive abscess (solid arrows, B) and no soft tissue gas. Clinical condition subsequently deteriorated, prompted surgical exploration revealing necrotic tissue, requiring orchiectomy.

FG without soft tissue or fascial gas on CT is uncommon but warrants awareness. Prior imaging series of FG have reported an incidence of 5-20% of patients with FG without gas on CT [1, 2] compared to 56% without gas in any necrotizing fasciitis of any anatomic site [3]. The factors in the CT scoring system other than fascial gas can help radiologists raise the possibility of FG without gas if there is an appropriate clinical suspicion. Cases of FG without fascial gas are shown in Figures 9 and 10.

CT and Clinical Scoring Systems for Necrotizing Fasciitis

A necrotizing fasciitis CT scoring system was described in a retrospective review of 305 patients with suspected soft tissue infections at any anatomic site that underwent CT to assess for necrotizing fasciitis [3]. CT findings significantly associated with necrotizing soft tissue infections when compared to patients without necrotizing fasciitis included fascial air, muscle/fascial edema, tracking fluid, lymphadenopathy, and subcutaneous edema. Assigning numeric scores to these CT findings, the authors developed a CT scoring system where a cumulative score of ≥6 was suggestive of necrotizing fasciitis. In a follow-up study [1] with 38 patients with surgically proven FG with preoperative CTs read independently by two blinded radiologists, the CT scores for necrotizing fasciitis were above the threshold score for all but one patient [1]. The factors in the scoring system are demonstrated in Table 1 and examples of each of the 5 factors in patients with FG are shown in Figure 11.

Table 1.

CT findings, definitions, and scores in the necrotizing soft tissue CT scoring system. A score of ≥6 is suggestive of necrotizing fasciitis. Imaging examples are shown in Figure 8. Reproduced with permission from [1].

CT findings, definitions, and scores in the necrotizing soft tissue CT scoring system. A score of ≥6 is suggestive of necrotizing fasciitis. Imaging examples are shown in Figure 11. Reproduced with permission from [1].

| CT Finding | Definitions | Points for CT scoring system |

|---|---|---|

| Fascial Air | Locules or tracts of air density through along fascial planes | 5 |

| Muscle/fascial edema | Thickening/indistinctness of fascial surface or muscle. Asymmetric appearance compared to contralateral side, if applicable. | 4 |

| Fluid tracking | More defined collection of fluid dissecting through soft tissue planes; more than would be accounted for by edema | 3 |

| Lymphadenopathy | Prominence of regional lymph nodes, asymmetric to the contralateral side when applicable. No specific size threshold was used. | 2 |

| Subcutaneous edema | Edema underlying an area of thickened skin. | 1 |

Figure 11.

Examples of the 5 factors in the CT scoring system for necrotizing fasciitis as defined in Table 1 in 5 different patients with surgically confirmed Fournier gangrene (two men [fascial air and subcutaneous edema] and three women [muscle/fascial edema, fluid tracking, and lymphadenopathy]).

There are two clinically utilized scoring systems for the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis and assessment of severity in Fournier gangrene. The laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis (LRINEC) was described in 2004 by Wong et al [24]. Though the specific parameters of the LRINEC scoring system are beyond the scope of this imaging review, the scoring system is derived from 6 hematologic and biochemical serum lab values and is used to meet a threshold score that is suggestive of necrotizing fasciitis. The Fournier gangrene scoring system was first described in 1995 by Laor et al [25] and is a modification of the acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II score. In contrast to the diagnostic purpose and scoring threshold of LRINEC, the Fournier gangrene scoring system is used in patients with known Fournier gangrene with higher scores being associated with increased mortality [25, 26].

Mimics

Any pathologic process that introduces gas and/or inflammation into fascial planes about the genitals, perineum, or perianal area may simulate necrotizing fasciitis on imaging. Squamous cell carcinoma may progress to an ulcerative wound or arise from a long-standing ulcer [12]. Most prevalent at the penis and labia, ulcerative squamous cell carcinoma of the genitals may simulate or introduce local gas. A case of squamous cell carcinoma mimicking FG on CT is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Necrotic tumor with gas. 46-year-old man with an ulcerative scrotal wound and clinical concern for Fournier gangrene. (A) Preoperative axial CT images demonstrate an ulcerative, open scrotal wound which has a small track of free air adjacent to the wound (arrow). (B) A fluid collection (dotted arrow) about the left testicle was concerning for an abscess or reactive hydrocele. At resection, the ulcerative wound was found to be squamous cell carcinoma.

Traumatic or iatrogenic gas introduced into the abdomen, pelvis, and proximal lower extremities may track into the genital or surrounding fascial planes. Fascial gas from trauma may originate from large volume pneumomediastinum, a pneumothorax with adjacent rib fracture, penetrating wounds, or a closed degloving injury [27] (Figure 13). Iatrogenic gas may be introduced during laparoscopic port insertions or removals or with traumatic insertion of Foley catheters.

Figure 13.

Gas spreading along fascial planes from trauma. 46-year-old man who fell from a ladder. (A) Initial radiograph of the left hip reveal fascial gas in the penis and scrotum (arrow), entertaining the possibility of Fournier gangrene (clinical history was not provided at that time). (B-D) CT revealed left-sided rib fractures (not pictured) propagating a left pneumothorax (thick arrow, B) with left body wall subcutaneous emphysema (arrows, B and C) traveling caudally to the scrotum and penis (arrow, D).

Vaginitis emphysematosa is an uncommon accumulation of gas about the vaginal wall mucosa that has a self-limiting course. Although the mechanism and etiology is debated, one of the most accepted theories is infection by Trichomonas vaginalis in immunocompromised women [28]. With a similar appearance to pneumatosis in the bowel, CT findings of emphysematous vaginitis include tiny cystic locules of gas that are usually confined to the vaginal wall [28] (Figure 14). Rare extension to the labia has been described [28], which may simulate FG.

Figure 14.

Vaginitis emphysematosa. 37-year-old woman with polysubstance abuse presenting with sepsis and infective endocarditis with incidentally noted vaginitis emphysematosa on CT. CT demonstrates a distended upper vagina with multiple locules of gas (solid arrows) outlining the vaginal wall (lumen demonstrated by the dashed arrow) and was interpreted as a likely manifestation of vaginitis emphysematosa. The diagnosis was confirmed when further testing demonstrated colonization and infection with Trichomonas vaginalis.

Conclusion

Although FG is often a clinical diagnosis, CT is useful in preoperative planning to adequately assess the affected fascial planes. Fascial air, muscle or fascial edema, and subcutaneous edema are the most common findings on CT. It is uncommon, but possible, for FG to manifest on imaging without fascial air. More modern series with FG suggest a rising incidence in women. Women are more likely to be morbidly obese (BMI>40) and almost always have labial or vulvar involvement of FG. Radiographs have a limited role in imaging FG. Scrotal ultrasound in males with suspected testicular complications may reveal sonographic manifestations of fascial air as bright hyperechoic reflectors and dirty shadowing. MR can be obtained to assess for FG but we do not recommend delaying operative management to perform an MR examination when CT is readily available. Radiologists play an important role as imaging of FG and necrotizing fasciitis is likely more prevalent given the availability of CT and its use for preoperative planning. It is helpful to realize the increasing incidence of FG in women, FG imaging appearances, and the potential usefulness of the CT scoring system in diagnosing and describing FG and necrotizing fasciitis.

Acknowledgments

DISCLOSURES: Dr. Pickhardt is an advisor to Bracco and shareholder in SHINE and Elucent; all authors claim no conflicts of interest or disclosures. Dr. Ballard receives salary support from National Institutes of Health TOP-TIER grant T32-EB021955. All author authors claim no conflicts or disclosures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conference Presentation:

Concepts and some cases from this manuscript was presented at the 2017 Radiologic Society of North American Annual Scientific Meeting:

Ballard DH, Raptis C, Mazaheri P, Patlas M, Lubner MG, Menias CO, Pickhardt P, Mellnick VM. Fournier Gangrene in Men and Women: What the Surgeon Wants to Know. Educational Exhibit with CME Presentation at: 2017 Radiological Society of North America Annual Meeting; Chicago, IL.

References:

- 1.Ballard DH, Raptis CA, Guerra J, et al. Preoperative CT Findings and Interobserver Reliability of Fournier Gangrene. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;211(5):1051–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wysoki MG, Santora TA, Shah RM, Friedman AC. Necrotizing fasciitis: CT characteristics. Radiology. 1997;203(3):859–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGillicuddy EA, Lischuk AW, Schuster KM, et al. Development of a computed tomography-based scoring system for necrotizing soft-tissue infections. J Trauma. 2011;70(4):894–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith GL, Bunker CB, Dinneen MD. Fournier’s gangrene. Br J Urol. 1998;81(3):347–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eke N Fournier’s gangrene: a review of 1726 cases. Br J Surg. 2000;87(6):718–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gürdal M, Yücebas E, Tekin A, Beysel M, Aslan R, Sengör F. Predisposing factors and treatment outcome in Fournier’s gangrene. Analysis of 28 cases. Urol Int. 2003;70(4):286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oguz A, Gümüş M, Turkoglu A, et al. Fournier’s Gangrene: A Summary of 10 Years of Clinical Experience. Int Surg. 2015;100(5):934–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ersay A, Yilmaz G, Akgun Y, Celik Y. Factors affecting mortality of Fournier’s gangrene: review of 70 patients. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77(1–2):43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basoglu M, Ozbey I, Atamanalp SS, et al. Management of Fournier’s gangrene: review of 45 cases. Surg Today. 2007;37(7):558–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koukouras D, Kallidonis P, Panagopoulos C, et al. Fournier’s gangrene, a urologic and surgical emergency: presentation of a multi-institutional experience with 45 cases. Urol Int. 2011;86(2):167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, et al. Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infection: Diagnostic Accuracy of Physical Examination, Imaging, and LRINEC Score: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Surg. 2019;269(1):58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker RA, Menias CO, Quazi R, et al. MR Imaging of the Penis and Scrotum. Radiographics. 2015;35(4):1033–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avery LL, Scheinfeld MH. Imaging of penile and scrotal emergencies. Radiographics. 2013;33(3):721–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levenson RB, Singh AK, Novelline RA. Fournier gangrene: role of imaging. Radiographics. 2008;28(2):519–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ballard DH, Sangster GP, Tsai R, Naeem S, Nazar M, D’Agostino HB. Multimodality Imaging Review of Anorectal and Perirectal Diseases with Clinical, Histologic, Endoscopic, and Operative Correlation, Part II: Infectious, Inflammatory, Congenital, and Vascular Conditions. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2018; [Ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kavoussi PK. Surgical, radiographic, and endoscopic anatomy of the male reproductive system In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 11th ed Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016: 498–515. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan CM, Whitman GJ, Chew FS. Radiologic-Pathologic Conferences of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Necrotizing fasciitis of the scrotum (Fournier’s gangrene). AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996; 166(5): 1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison D, Blaivas M, Lyon M. Emergency diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene with bedside ultrasound. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23(4):544–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andipa E, Liberopoulos K, Asvestis C. Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound evaluation of penile and testicular masses. World J Urol. 2004;22(5):382–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shellock FG, Rothman B, Sarti D. Heating of the scrotum by high-field-strength MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154(6):1229–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoneda A, Fujita F, Tokai H, et al. MRI can determine the adequate area for debridement in the case of Fournier’s gangrene. Int Surg. 2010;95(1):76–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kickuth R, Adams S, Kirchner J, Pastor J, Simon S, Liermann D. Magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(5):787–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okizuka H, Sugimura K, Yoshizako T. Fournier’s gangrene: diagnosis based on MR findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992; 158(5): 1173–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong C-H, Khin L-W, Heng K-S, Tan K-C, Low C-O. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1535–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laor E, Palmer LS, Tolia BM, Reid RE, Winter HI. Outcome prediction in patients with Fournier’s gangrene. J Urol. 1995;154(1):89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corcoran AT, Smaldone MC, Gibbons EP, Walsh TJ, Davies BJ. Validation of the Fournier’s gangrene severity index in a large contemporary series. J Urol. 2008;180(3):944–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandstrom CK, Osman SF, Linnau KF. Scary gas: a spectrum of soft tissue gas encountered in the axial body (part II). Emerg Radiol. 2017;24(4):401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leder RA, Paulson EK. Vaginitis emphysematosa: CT and review of the literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(3):623–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]