Abstract

We previously reported a novel SAR campaign that converted a metabolically unstable series of μ-opioid receptor (MOR) agonist/ δ-opioid receptor (DOR) antagonist bicyclic core peptidomimetics with promising analgesic activity and reduced abuse liabilities into a more stable series of benzylic core analogues. Herein, we expanded the SAR of that campaign and determined that the incorporation of amines into the benzylic pendant produces enhanced MOR-efficacy in this series, whereas the reincorporation of an aromatic ring into the pendant enhanced MOR-potency. Two compounds, which contain a piperidine (14) or an isoindoline (17) pendant, retained the desired opioid profile in vitro, possessed metabolic half-lives of greater than 1 hour in mouse liver microsomes (MLM), and were active antinociceptive agents in the acetic acid stretch assay (AASA) at subcutaneous doses of 1 mg/kg.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction:

Opioid analgesics are the gold standard for the treatment of chronic and severe pain, however opioid induced analgesia comes with the risk of substance abuse, tolerance, dependence, and potentially fatal respiratory depression. To this end, considerable effort has been expended to develop drugs that possess the same analgesic effect of opioids without their negative side-effects. Opioid ligands that simultaneously target multiple opioid receptors have been an attractive avenue of research in this regard, and those that target MOR and DOR to reduce side effects can be divided into two different categories: MOR-agonist/DOR-antagonist, and MOR-agonist/DOR-agonist. Attenuated activity at DOR, either through DOR antagonists1–3 or DOR knockout,4,5 has been shown to reduce tolerance development and physical dependence to morphine in mice. Many MOR-agonist/DOR-antagonist bifunctional ligands have also shown decreased incidence of withdrawal and tolerance to antinociceptive effects,6–10 with some also showing reduced conditioned-place preference11,12 and respiratory depression.12 Curiously, DOR-agonism, instead of antagonism, has also been shown to reduce the side-effect profile of MOR-agonists. Coadministration of DOR-agonists with MOR-agonists has been shown to attenuate physical dependence13 and respiratory depression14 without affecting antinociception. These beneficial effects appear to work both ways, as MOR-agonists can attenuate the convulsive effects associated with activation of DOR.15 To this end, many MOR-agonist/DOR-agonist ligands have been synthesized and shown to have reduced abuse profiles, including reduced physical dependence,16 and tolerance to antinociception.17–19 The development of many of these ligands that target MOR and DOR has been reviewed recently.20,21

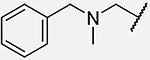

Given the potential of these ligands to produce antinociception with reduced adverse effects, our lab has been developing a promising MOR-agonist/DOR-antagonist peptidomimetic series containing a tetrahydroquinoline (THQ) core.11,22–30 As stability is an issue in this series, we recently reported an initial SAR study that showed it was possible to eliminate part of the tetrahydroquinoline core of these peptidomimetics and maintain the desired MOR-agonist/DOR-antagonist profile.31 While this approach proved useful for improving metabolic stability, we wished to enhance the potency and efficacy of these compounds at MOR and further increase their stability. Since these new monocyclic ligands had a high cLogP, we were also interested in analogues that would be less lipophilic in order to reduce their propensity to metabolism by CYP enzymes.32 In our original tetrahydroquinoline core peptidomimetics, we showed that amine pendants either maintain or improve efficacy and potency at MOR (Figure 1).25,30 These amine pendants also reduced cLogP when compared to their benzyl pendant counterpart. As such, we opted to introduce these polar amine pendants into our recently described benzylic core system. These compounds should retain or display improved MOR-efficacy and potency while further improving metabolic stability through their reduced cLogP.32 We present here the results of an SAR campaign aimed at combining these two structural elements.

Figure 1:

Design path leading to more stable peptidomimetics with amine pendants. Blue indicates previously reported SAR. Red indicates combined strategies reported in this work.

Results:

General Chemistry:

In order to incorporate basic amine pendants into our series, we began by introducing the ethyl ether into our scaffold using Scheme 1. This was done by taking commercially available methyl 3-formyl-4-hydroxybenzoate (1) and alkylating the phenol with ethyl bromide and potassium carbonate, yielding 2. This aldehyde was then subjected to a reductive amination using an Ellman’s chiral sulfinamide as an amine source to produce 3. The auxiliary was left on the scaffold, as it served as a protecting group for the subsequent LiOH mediated saponification, of which compound 4 was isolated as a lithium carboxylate. This served as a point of diversification, whereby different amines were coupled to the carboxylate anion. The carboxylate was not reduced before the pendant attachment because we were interested in the effect an amide in this position had on our SAR. This amide was then deprotected with concentrated HCl forming analogues 5–12. It should be noted that purification by reverse phase HPLC yielded these analogues as the TFA salt. If desired, these amides were reduced with borane-dimethyl sulfide complex at 75 °C and then coupled to Boc protected 2’,6’-L-Dimethyltyrosine (DMT) and the Boc groups were subsequently removed with TFA.

Scheme 1:

Synthesis of Amine or Amide Pendant Analogues with an Ethyl Ether on the Benzylic Core

A) EtBr, K2CO3, DMF. B) 1. (R)-(+)-2-methyl-2-propanesulfinamide, Ti(OEt)4, THF 2. NaBH4. C) LiOH, THF, EtOH, H2O D) 1. NHR1R2 2, NMM, PyBOP, DMF. 2. conc. HCl, Dioxane. E) BH3*Me2S, THF, 75 C° F) 1. DiBocDMT, DIEA, PyBOP, 6-Cl-HOBt, DMF. 2. TFA, DCM.

SAR:

Our studies began by selecting the monocyclic analogue from the previous series with the best MOR/DOR profile, namely that containing the ethyl ether31 (Table 1, Lead). We were encouraged by the stability of this analogue, as this was ten times more stable than the original tetrahydroquinoline peptidomimetic.31 We began by replacing the benzyl pendant with various cyclic basic amines (Table 1), some of which were previously reported in our THQ series.25 These included piperidine (14), morpholine (16), isoindoline (17), and tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ, 18) ring systems. A few novel pendants in this series were also evaluated for opioid activity, namely the pyrrolidine (13) and 3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane (15) heterocycles, and two conformationally flexible benzyl amine analogues (19 and 20). Finally, these derivatives were complemented with the amide analogues of the pyrrolidine (21) and isoindoline (22) pendants. For the sake of completeness, each of these analogues was also screened against the κ-opioid receptor (KOR).

Table 1:

Binding affinity of the benzylic core compounds at MOR, DOR, and KOR. Binding affinities (Ki) were obtained by competitive displacement of radiolabeled [3H] diprenorphine in CHO membrane preparations overexpressing a single human opioid receptor. Included is the Lead and morphine for comparison. All data were from at least three independent experiments, performed in duplicate. Selectivity was calculated by dividing the Ki of each receptor by the Ki at MOR for a given compound. These data are reported as the average ± standard error of the mean.

|

Binding Affinity, Ki (nM) ± SEM | Selectivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | R | MOR | DOR | KOR | MOR:DOR:KOR |

| Morphine | - | 4.2±1.3 | 104.1±9.1 | 36.8±9.4 | 1:25:8.9 |

| Lead |  |

3.6±0.5 | 4.8±0.9 | 1200±120a | 1:1.3:333 |

| 13 |  |

15.0±1.8 | 44.4±7.9 | 430±16 | 1:3.0:29 |

| 14 |  |

5.0±1.5 | 15.7±4.3 | 101±14 | 1:3.1:20 |

| 15 |  |

19.6±6.1 | 50±10 | 247±51 | 1:2.6:13 |

| 16 |  |

38.0±9.9 | 76.0±4.5 | >1870 | 1:2.0:>49 |

| 17 |  |

0.80±0.22 | 2.7±0.6 | 243±53 | 1:3.4:338 |

| 18 |  |

0.23±0.04 | 2.4±0.5 | 44.2±4.6 | 1:10:192 |

| 19 |  |

0.45±0.13 | 0.82±0.27 | 23.2±7.5 | 1:1.2:52 |

| 20 |  |

0.48±0.13 | 1.93±0.36 | 12.4±0.5 | 1:4.0:26 |

| 21 |  |

33±11 | 74±23 | >716 | 1:2.2:>22 |

| 22 |  |

0.29±0.05 | 5.9±2.0 | 261±12 | 1:20:900 |

From reference31.

Compared to the lead compound, monocyclic amine pendant analogues with the exception of piperidine analogue 14, showed a loss in MOR binding affinity, in contrast to the bicyclic amine analogues (17–18) which showed improvements in binding affinity (Table 1). The monocyclic amines also demonstrated losses in DOR binding affinity as compared to the Lead compound, whereas the bicyclic amines produced no change in affinity for this receptor. Neither the benzyl amines (19–20) nor the amides (21–22) were significantly different from their cyclic amine counterparts in their affinities for MOR or DOR. KOR affinity was generally higher than the Lead compound with each of these amine pendant analogues, the only exception being the morpholine pendant (16). The highest binding affinity at KOR comes from the benzyl amine analogues (19–20), with binding affinity in the low double-digit nanomolar range. The selectivity ratio was also determined for each of these analogues. In general, a binding affinity balance no greater than 1:4 was maintained between MOR and DOR, the only exceptions being the THIQ analogue 18 and the isoindoline amide analogue 22. Selectivity of MOR over KOR was reduced for most analogues, though this selectivity was maintained with a ratio of at least 1:192 with the bicyclic analogues 17, 18, and 22. Notably, the new analogues that contained an aromatic ring (17–20, 22) displayed improved binding affinity at MOR and DOR compared with morphine.

With regards to potency at MOR, a variety of effects were observed (Table 2) in the functional [35S] GTPγS binding assay. The pyrrolidine (13) and piperidine (14) were less potent than the Lead. Incorporation of the cyclopropyl group (15) onto the pyrrolidine, or conversion from a piperidine to a morpholine pendant (16) reduced this potency further. Analogues that reincorporated an aromatic ring (17–20) showed improvements in MOR potency compared to both the Lead and morphine, which was more pronounced if the aromatic ring was locked in a bicyclic pendant (17–18). The most interesting data obtained in this series is the efficacy at MOR. Notably, the greatest improvements in efficacy were with the bicyclic amine pendants (17–18), which were full agonists compared to the standard MOR-agonist DAMGO and morphine. Variable levels of DOR activity were observed in these amine pendants. Some were partial DOR agonists, having either low (13–15), moderate (17), or high (19) potency. The morpholine (16), THIQ (18), N-methyl benzyl amine (20), and amides (21–22) did not stimulate DOR. Finally, none of these compounds had any appreciable efficacy at KOR up to 1.0 μM.

Table 2:

Potency and efficacy of the benzylic core compounds at MOR, DOR, and KOR. Efficacy and potency data were obtained using agonist induced stimulation of [35S] GTPγS binding assay. Potency is represented as EC50 (nM) and efficacy as percent maximal stimulation relative to standard agonist DAMGO (MOR), DPDPE (DOR), or U69,593 (KOR) at 10 μM. Included is the Lead and morphine for comparison. All data were from at least three independent experiments, performed in duplicate. These data are reported as the average ± standard error of the mean. DNS=Does Not Stimulate

| Potency, EC50 (nM) ± SEM | Efficacy (% Stimulation) ± SEM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | R | MOR | DOR | KOR | MOR | DOR | KOR |

| Morphine | - | 147±48 | >593 | DNS | 98.5±3.8 | >30 | DNS |

| Lead |  |

72±13 | DNS | DNSa | 75.5±5.8 | DNS | DNSa |

| 13 |  |

168±42 | 1360±96 | >6000 | 85.9±9.7 | 55±11 | >40 |

| 14 |  |

585±73 | 129±20 | DNS | 77.5±5.8 | 36.8±6.7 | DNS |

| 15 |  |

990±160 | 460±100 | >10000 | 88±16 | 52.1±7.0 | >36.4 |

| 16 |  |

1020±290 | DNS | DNS | 75±11 | DNS | DNS |

| 17 |  |

8.4±1.2 | 43±13 | DNS | 98.1±6.7 | 35.7±2.8 | DNS |

| 18 |  |

1.9±0.5 | DNS | DNS | 94.6±3.9 | DNS | DNS |

| 19 |  |

16.7±4.8 | 4.7±2.0 | >1000 | 77.9±3.0 | 26.1±1.7 | >20 |

| 20 |  |

33.9±4.3 | DNS | DNS | 72.2±6.2 | DNS | DNS |

| 21 |  |

DNS | DNS | DNS | DNS | DNS | DNS |

| 22 |  |

15.0±3.3 | DNS | DNS | 27.8±0.7 | DNS | DNS |

From reference31.

Metabolic Stability:

Since improved metabolic stability remained a goal, most of the ligands synthesized herein were examined for stability in mouse liver microsomes (MLM) (Table 3). The ligands selected met one of two criteria: they possessed EC50 values at MOR less than 1 μM, or they probed the importance of the amine pendant in this series (namely through the amides). As such, the 3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane analogue 15 and the morpholine analogue 16 were excluded. For comparison, the previously reported benzyl pendant (Lead) was again included, as well as the stability ratio between each compound and the positive control verapamil. This ratio was used due to the variability in the half-life of the positive control verapamil between assays. Conversion to the simple pyrrolidine (13) or piperidine (14) pendants produced a significant boost in metabolic stability, providing stability ratios of 6.6 and 3.3 with half-lives of 199 and 99 min respectively. The attachment of aromatic rings to form the isoindoline (17) and THIQ (18) pendants attenuated these stability improvements, however the isoindoline stability was still greater than that of the original benzyl pendant. Breaking the THIQ pendant of 18 produced differential effects, as the benzylamine analogue (19) showed no change in stability, while the N-methyl benzylamine (20) caused stability loss. Finally, the amide analogues of 13 and 17 (21 and 22, respectively) either produced a minor loss, or a minor gain in stability compared to their amine counterparts.

Table 3:

Metabolic stability of monocyclic compounds in MLM. Included are the compound half-life (T1/2), the half-life of the positive control verapamil, and the stability ratio between the compound and the positive control. The stability ratio was calculated by dividing the half-life of the analogue of interest by the half-life of the positive control in that assay. Individual compounds were tested once, with errors representing the SE in the decay curve regressed onto the data collected in 15 minute intervals. The cLogP of these analogues were calculated using PerkinElmer’s ChemDraw® Professional Software.

| Name | R1 | T1/2 (min) | Verapamil T1/2 (min) | Stability Ratio | cLogP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead |  |

23.7±5.9a | 14.6±1.0a | 1.6±0.4a | 4.75a |

| 13 |  |

199±79 | 29.9±4.7 | 6.6±2.8 | 3.15 |

| 14 |  |

99.2±4.3 | 29.9±4.7 | 3.3±0.5 | 3.71 |

| 17 |  |

70.4±7.5 | 25.7±1.7 | 2.7±0.3 | 4.11 |

| 18 |  |

52.9±8.3 | 29.9±4.7 | 1.8±0.4 | 4.57 |

| 19 |  |

51.5±1.8 | 27.6±4.9 | 1.9±0.3 | 3.21 |

| 20 |  |

39.2±1.5 | 27.6±4.9 | 1.4±0.2 | 4.28 |

| 21 |  |

137±47 | 25.7±1.7 | 5.3±1.9 | 2.08 |

| 22 |  |

97±12 | 29.9±4.7 | 3.3±0.6 | 3.56 |

From reference31

Antinociceptive Activity:

Analogues 13–14 and 17–20 were also screened for antinociceptive activity (Figure 2A–C) using the acetic acid stretch assay (AASA). Morphine was used as a positive control. Additional details for this assay are found in the experimental section. Two analogues were inactive in this assay, namely the pyrrolidine analogue 13 and the N-methylbenzyl amine analogue 20. Three analogues showed antinociception at 10 mg/kg (Lead, 18, and 19) when administered subcutaneously (sc). Finally, the piperidine (14) and isoindoline (17) analogues were both active at 1 mg/kg sc. It is important to note that no behavioral changes were observed in the test animals. There were no noticeable DOR or KOR mediated behavioral effects (convulsions, sedation) nor were there any centrally mediated MOR effects (Straub tail, locomotion).

Figure 2:

Antinociceptive activity of the Lead and analogues 13–14, and 17–20 using the AASA. Included is morphine (M) (1 mg/kg) as positive control. Panels A-C represent dose-response curves with the ligands: A) Lead and monocyclic amine analogues 13 and 14, B) bicyclic amine analogues 17 and 18 C) benzyl amine analogues 19 and 20. * P<0.05 compared to vehicle. ** P<0.01 compared to vehicle. ***P<0.001 compared to vehicle. **** P<0.0001 compared to vehicle. D) Competition assays between each analogue active at 10 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg of the opioid antagonist naloxone in the AASA. ## P<0.01 (drug - nlx) vs (vehicle - nlx). ### P<0.001 (drug - nlx) vs (vehicle - nlx). #### P<0.0001 (drug - nlx) vs (vehicle - nlx). * P<0.05 (drug - nlx) vs (drug + nlx). ** P<0.01 (drug - nlx) vs (drug + nlx). Data shown are means ± SEM for all groups (n = 6 for each group); statistical comparisons were performed using a two-way ANOVA.

We next sought to confirm that antinociception was mediated through the opioid receptors. To this end, each mouse was pretreated with a 10 mg/kg dose of the nonselective opioid receptor antagonist naloxone (NLX) (Figure 2D) before treatment with 10 mg/kg of each active ligand from above. If the observed antinociception is opioid mediated, it will be attenuated by pretreatment with naloxone. For each analogue tested, the administration of naloxone inhibited the antinociceptive response induced in the AASA. This confirmed that the antinociception observed for these analogues is opioid receptor mediated.

Discussion and Conclusion:

SAR:

Within the analogues found in Table 1, it appears that most of the monocyclic amine pendants produced a marked loss in binding at MOR. However, those that contain an aromatic ring (17–20, 22) instead show improved binding at MOR. Conversion of the amine to an amide (13 to 21, 17 to 22) produced no significant difference in this binding affinity. This suggests that the aromatic ring is an important component for MOR binding, whereas the amine is not. Similar trends can be observed for DOR binding.

In general, increases in binding affinity to KOR as compared to Lead were observed for these analogues. This is likely a result of polarity around the attachment point of the pendant to the rest of the molecule, as conversion between the amine and the amides of the pyrrolidine (13 and 21) and the isoindoline (17 and 22) produced similar affinities at KOR. The highest binding affinity at KOR came with the benzyl amine analogues (19-20), and suggested that additional conformational flexibility enabled stronger binding affinity at KOR, as compared to their conformationally restricted counterparts (17-18)

The trends in MOR potency of these analogues as measured by the [35S] GTPγS binding assay were consistent with their affinity at MOR. Aromatic rings appeared to be important in these new pendants for high potency, whereas the amine does not appear to be vital (as exemplified by 22). Conversely, every compound containing an amine group displayed high efficacy at MOR. Converting the amine into an amide drastically reduced efficacy as evidenced by 17 and 22. This suggests either that this amine is an important pharmacophore element for activation of MOR, or that the amide conjugation with the aromatic ring prevented the pendant from adopting an orientation necessary to activate MOR. While these amines may display efficacy at MOR, alone they do not improve potency. However, attachment of an aromatic ring greatly improved potency, and increased potency compared to the original benzyl pendant. It thus appears that the amine in these pendants is important for maintaining full efficacy, whereas the aromatic ring is important for high potency. This combination may therefore be a useful pharmacophore for producing future MOR-agonists.

Interestingly, half of these amine compounds produced some DOR stimulation. Following a similar trend in MOR, this agonism at DOR was abolished upon conversion to the amide, suggesting the amine is contributing to DOR activity. The incorporation of an aromatic ring also appears to improve the potency of these compounds at DOR (when applicable), namely through comparison between 13 and 17. However, it should be noted that the efficacy here decreased with these aromatic rings, and except for 16, the only MOR-agonists that did not stimulate DOR in this series possessed an aromatic ring. As such, it appears that the additional aromatic ring can reduce the efficacy at DOR of these compounds. Finally, none of these compounds had any appreciable ability to activate KOR. The benzyl amines 19 and 20 did have low double-digit nanomolar affinity at KOR, and thus may be further developed into KOR ligands.

Computational Modeling:

Computational modeling studies of analogue 17 docked into experimental structures of opioid receptors helped to explain our observed SAR data. Analogue 17 can be accommodated without hindrances in the binding pocket in the structure of the active conformation of MOR (PDB ID: 6ddf), forming H-bonds with D147 from TM3 and H297 from TM6 (Fig. 3A). The distance between the positively charged amine of the pendant and D216 from the extracellular loop 2 (EXL-2) is ~6 Å, which is ~1 Å smaller than that in the inactive conformation of MOR (PDB ID: 4dkl). We can suggest that this amine group may promote the inward movement of D216 and EXL-2, thus causing the contraction of the pocket and receptor activation. Indeed, this would be consistent with a comparison of crystal structures of GPCRs in active and inactive states whereby the orthosteric binding pocket becomes smaller upon receptor activation.33

Figure 3:

Computational modeling of analogue 17 to A) MOR in the active state (PDB ID: 6ddf), B) DOR in the inactive state (PDB ID: 4rwa), and C) KOR in the inactive state (PDB ID: 4djh).

Analogue 17 also fits the binding pocket of the inactive conformation of DOR (PDB ID: 4rwa), forming H-bonds with D128 from TM3, while the OH group of DMT may interact through a water molecule (distance ~6 Å) with H278 from TM6 (Fig. 3B). This may explain the rather high binding affinity of 17 to DOR.

Analogue 17 cannot be accommodated in the orthosteric pocket of the KOR-active state (PDB ID: 6b73) due to hindrances between ligand and I294 from TM6 (V300 in MOR, V281 in DOR) and Y312 from TM7 (W318 in MOR, L300 in DOR). In the inactive conformation of KOR (PDB ID: 4djh), the binding site for the aromatic-amine pendant is too large, so the van der Waals interactions between ligand and receptor are weakened (Fig. 3C). This is consistent with the weak binding affinity of 17 to KOR and its inability to activate the receptor.

Metabolic Stability:

The conversion from the benzyl pendant to the pyrrolidine and piperidine pendants produced a marked improvement in metabolic stability. This can be attributed to the reduced cLogP of these two pendants, which is known to reduce binding affinity to cytochrome P450 enzymes.32 Two different groups of exceptions exist. The first being the benzyl amine analogues 19 and 20, which have lower stability than predicted by their cLogP. This could be attributed to their increased conformational flexibility in relation to the amine and the aromatic ring, allowing more binding orientations within the CYP enzyme. Furthermore, the amides 21 and 22 also have lower stability than predicted by their cLogP. These amides are conjugated to the ethyl ether through the aromatic core, possibly facilitating elimination of the ethyl group at the end of the CYP catalytic cycle.

Antinociceptive Activity:

Of the MOR agonists tested in vivo, only the pyrrolidine (13) and the N-methylbenzyl (20) amine pendants lacked antinociceptive activity. Conversely, the piperidine (14) and the isoindoline (17) analogues were active at 1 mg/kg sc. Within this set of analogues, there appeared to be no obvious trends that dictate which analogues were active in vivo. In vitro MOR potency did not appear to be a driving force for antinociceptive activity, as the piperidine 14 has relatively low potency compared to the other tested analogues. The presence of an aromatic ring also did not appear to be a necessary factor for activity in these analogues, as the piperidine 14 is active and the N-methylbenzyl 20 is not. As such, further derivatization may be necessary for any clear trends to emerge.

Conclusion:

The analogues described here (such as 14 and 17) represent a promising direction for further development of these opioid peptidomimetics. It appears that the amine in the pendant can contribute to high efficacy at MOR, whereas the re-incorporation of an aromatic ring into the pendant yields high potency at MOR. This was largely insensitive to flexibility in the pendant, as illustrated by the two benzyl amine analogues. These pendants also enabled improved metabolic stability as compared to our previously reported analogues. Particularly noteworthy, is the isoindoline analogue 17, which combines enhanced stability with improved MOR efficacy and potency. Finally, several of these compounds produced antinociceptive activity in vivo in the AASA and this antinociception is mediated through opioid receptors. Given the progress that these pendants have provided us, future analogues will use these pendants as a key element in their design and may lead us closer to developing an opioid analgesic with reduced side-effects.

Experimental:

Chemistry

General Methods:

All reagents and solvents were obtained commercially and were used without further purification. Intermediates were purified by flash chromatography using a Biotage Isolera One instrument. Most purification methods utilized a hexanes/ethyl acetate or dichloromethane/methanol solvent systems in a Biotage SNAP KP-Sil column using linear gradients. Reverse phase column chromatography using a linear gradient of 0 % to 100 % solvent B (0.1 % TFA in acetonitrile) in solvent A (0.1 % TFA in water) using a Biotage SNAP Ultra C18 column was utilized for intermediate amine salts. Purification of final compounds was performed using a Waters semipreparative HPLC with a Vydac protein and peptide C18 reverse phase column, using a linear gradient of 0 % to 100 % solvent B in solvent A at a rate 1 % per minute, monitoring UV absorbance at 230 nm. The purity of final compounds was assessed using a Waters Alliance 2690 analytical HPLC instrument with a Vydac protein and peptide C18 reverse phase column. A linear gradient (gradient A) of 0 % to 70 % solvent B in solvent A in 70 min, measuring UV absorbance at 230 nm was used to determine purity. All final compounds used for testing were ≥95 % pure, as determined by analytical HPLC. 1H NMR and 13C NMR data were obtained on a 500 or 400 MHz Varian spectrometer using CDCl3, CD3OD, DMSO-d6, or D2O as solvents. The identities of final compounds were verified by mass spectrometry using an Agilent 6130 LC–MS mass spectrometer in the positive ion mode, or an Agilent 6230 TOF HPLC-MS in the positive ion mode.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of 6-position Ethers (Procedure A):

To a flame dried flask containing methyl 3-formyl-4-hydroxybenzoate (1) was added 3 equivalents of potassium carbonate. The flask was purged with argon and 4 mL of DMF was added. 3 equivalents of ethyl bromide were then added, and the solution was stirred at room temperature overnight. The solution was then concentrated in vacuo, partitioned between ethyl acetate and saturated sodium carbonate, and extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layers were combined, dried with magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo, yielding the desired ether (2).

General Procedure for Ellman Reductions (Procedure B):

A flamed-dried round bottom flask containing 1 equivalent of aldehyde (2) and 3 equivalents of (R)-(+)-2-methyl-2-propanesulfinamide was attached to a reflux condenser and flushed with argon. 4 mL of THF was added and cooled to 0 °C. 6 equivalents of titanium (IV) ethoxide was added, followed by an additional 4 mL of THF. The solution was stirred and heated to 75 °C overnight with TLC monitoring until all ketone or aldehyde was consumed. A separate flame-dried flask containing 6 equivalents of sodium borohydride was flushed with argon. 4 mL of THF was added to this flask, at which point the solution was cooled to −78 °C. The solution containing Ellman adduct was cooled to room temperature and slowly transferred to the sodium borohydride solution via syringe. This final solution was then allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 2 hours, at which point the reaction mixture was quenched with methanol to consume the sodium borohydride, followed by DI water to precipitate the titanium. The solution was vacuum filtered, and the precipitate was washed with ethyl acetate. The filtrate was the concentrated in vacuo and purified via column chromatography (0–100% EtOAc in Hexanes), yielding the desired sulfinamide (3).

General Procedure for the Saponification of Esters (Procedure C):

To a flask containing 1 equivalent of the ester (3) was added 7 equivalents of LiOH, 2 mL of THF, 2 mL of EtOH, and 2 mL of H2O. The reaction was stirred overnight under ambient atmosphere and temperature. Upon completion, the solvent was concentrated in vacuo, suspended in acetone, and filtered. The precipitate was washed with additional acetone, and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo, yielding the saponified product as a lithium carboxylate (4).

General Procedure for Amine Pendant Attachment and Cleavage of Ellman Auxiliaries (Procedure D):

To a flask containing 1 equivalent of the lithium carboxylate (4) was added 1 equivalent of PyBOP and 1 equivalent of the desired amine. The flask was flushed with argon, DMF was added as solvent, and 10 equivalents of N-methylmorpholine was added. The reaction was stirred overnight, at which point it was concentrated in vacuo and purified via column chromatography (0–10% methanol in DCM). To the protected amine was immediately added 2 mL of Dioxane and 0.2 mL concentrated HCl. The solution was stirred at room temperature for 1 minute and concentrated in vacuo. The ensuing salt was triturated with diethyl ether and was further purified using reverse phase chromatography (0–100% B in A), yielding the product as a TFA salt.

General Procedure for the Reduction of Pendant Amides (Procedure E):

To a dried flask containing 1 equivalent of the desired amide under argon was added THF and 7 equivalents of 2 M BH3*Me2S complex in THF. The reaction was heated at 75 °C for 3 hours, at which point the reaction was quenched with MeOH and heated for an additional 15 minutes. The reaction was then cooled, concentrated in vacuo, and was used in Procedure F without further purification.

General Procedure for the Coupling of 2’,6’-Dimethyltyrosine to Functionalized Amine Salt (Procedure F):

To a dried flask containing the amine under argon was added 3 mL of DMF and 10 equivalents of Hunig’s base. 1 equivalent of PyBOP and 1 equivalent of 6-Cl-HOBt was added, followed by a 1 equivalent of N-Boc-O-Boc-2’,6’-dimethyl-L-tyrosine in 1.5 mL DMF. The solution was stirred overnight at room temperature, concentrated in vacuo, and purified via semipreparative reverse phase HPLC (0.1% TFA in water: 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile). 2 mL of TFA and 2 mL of DCM were then added, and the solution was stirred for an additional hour. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo and purified via an additional semipreparative reverse phase HPLC (0.1% TFA in water: 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile). The product was concentrated in vacuo and lyophilized overnight to yield the final peptidomimetic.

Methyl 4-ethoxy-3-formylbenzoate (2):

See Procedure A: 149 mg (0.83 mmol) of methyl 3-formyl-4-hydroxybenzoate (1), 342 mg (2.47 mmol, 2.99 eq.) of K2CO3, 190 μL (277 mg, 2.55 mmol, 3.08 eq) of EtBr, 4 mL of DMF. Compound 2 (162 mg, Yield=94 %) was isolated as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 10.46 (s, 1H), 8.47 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.19 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.21 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 1.50 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 188.93, 166.00, 164.25, 137.01, 130.35, 124.33, 122.63, 112.22, 64.68, 52.07, 14.49.

Ethyl (R)-3-(((tert-butylsulfinyl)amino)methyl)-4-ethoxybenzoate (3):

See Procedure B: Step 1: 149 mg (0.72 mmol) of 2, 262 mg (2.16 mmol, 3.02 eq.) of (R)-(+)-2-methyl-2-propanesulfinamide, 900 μL (979 mg, 4.3 mmol, 6.0 eq.) of Ti(OEt)4, 4+4 mL THF. Step 2: 165 mg (4.4 mmol, 6.1 eq.) of sodium borohydride in 4 mL THF. Compound 3 (232 mg, Yield= 99 %) was isolated as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.95 (m, 2H), 6.85 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 4.41 (dd, J = 14.3, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 4.32 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.20 (dd, J = 14.3, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.11 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.74 (dd, J = 7.8, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 1.44 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.36 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.21 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 166.26, 160.35, 131.05, 130.61, 127.10, 122.49, 110.50, 63.94, 60.67, 55.87, 45.18, 22.60, 14.73, 14.34.

Lithium (R)-3-(((tert-butylsulfinyl)amino)methyl)-4-ethoxybenzoate (4):

See Procedure C: 208 mg (0.64 mmol) of 3, 198 mg (8.27 mmol, 12.9 eq.) of LiOH, 2 mL of THF, 2 mL of EtOH, and 2 mL of H2O. Compound 4 (172 mg, Yield= 89 %) was isolated as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.91 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.34 (d, J = 14.3 Hz, 1H), 4.23 (d, J = 14.3 Hz, 1H), 4.12 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.44 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.22 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 173.90, 158.48, 130.37, 130.12, 129.54, 125.96, 109.79, 63.44, 55.64, 44.31, 21.73, 13.81.

(2-ethoxy-5-(pyrrolidine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)methanaminium trifluoroacetate (5):

See Procedure D: Step 1: 28 mg (0.092 mmol) of 4, 49 mg (0.094 mmol, 1.0 eq.) of PyBOP, 20 μL (17 mg, 0.24 mmol, 2.7 eq.) of pyrrolidine, 100 μL (92 mg, 0.91 mmol, 9.9 eq.) of NMM, and 4 mL of DMF. Step 2: 2 mL of dioxane and 0.2 mL conc. HCl. Compound 5 (33 mg, Quant Yield) was isolated as a yellow oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.61 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 4.22 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 4.15 (s, 2H), 3.57 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.51 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 1.99 (p, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 1.89 (p, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 1.47 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 169.75, 158.69, 130.16, 129.66, 128.32, 126.99, 111.15, 64.29, 49.81, 46.41, 38.49, 25.88, 23.92, 13.52.

(2-ethoxy-5-(piperidine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)methanaminium trifluoroacetate (6):

See Procedure D: Step 1: 27 mg (0.088 mmol) of 4, 46 mg (0.088 mmol, 1.0 eq.) of PyBOP, 20 μL (17 mg, 0.20 mmol, 2.3 eq.) of piperidine, 100 μL (92 mg, 0.91 mmol, 10.3 eq.) of NMM, and 4 mL of DMF. Step 2: 2 mL of dioxane and 0.2 mL conc. HCl. Compound 6 (28 mg, Yield= 84 %) was isolated as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.47 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.22 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 4.14 (s, 2H), 3.68 (br s, 2H), 3.44 (br s, 2H), 1.76 – 1.68 (m, 2H), 1.64 (br s, 2H), 1.57 (br s, 2H), 1.48 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 170.20, 158.22, 129.74, 129.42, 127.91, 121.26, 111.19, 64.17, 38.48, 24.02, 20.05, 13.41.

(5-(3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-3-carbonyl)-2-ethoxyphenyl)methanaminium trifluoroacetate (7):

See Procedure D: Step 1: 25 mg (0.082 mmol) of 4, 41 mg (0.079 mmol, 0.96 eq.) of PyBOP, 12 mg, (0.10 mmol, 1.2 eq.) of 3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane hydrochloride, 90 μL (83 mg, 0.82 mmol, 10.0 eq.) of NMM, and 4 mL of DMF. Step 2: 2 mL of dioxane and 0.2 mL conc. HCl. Compound 7 (21 mg, Yield=69 %) was isolated as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.54 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 4.22 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 4.14 (s, 2H), 4.07 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 3.75 (dd, J = 10.9, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 3.51 – 3.42 (m, 2H), 1.60 (ddt, J = 20.4, 7.1, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 1.48 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 0.72 (td, J = 7.7, 5.2 Hz, 1H), 0.10 (q, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 170.61, 158.46, 130.07, 129.60, 128.61, 126.97, 111.01, 64.19, 51.35, 38.45, 20.05, 15.41, 13.73, 13.41, 7.57.

(2-ethoxy-5-(morpholine-4-carbonyl)phenyl)methanaminium trifluoroacetate (8):

See Procedure D: Step 1: 29 mg (0.095 mmol) of 4, 50 mg (0.096 mmol, 1.0 eq.) of PyBOP, 20 μL (20 mg, 0.23 mmol, 2.4 eq.) of morpholine, 110 μL (101 mg, 1.0 mmol, 10.5 eq.) of NMM, and 4 mL of DMF. Step 2: 2 mL of dioxane and 0.2 mL conc. HCl. Compound 8 (28 mg, Yield= 78 %) was isolated as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.51 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.23 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 4.15 (s, 2H), 3.78 – 3.50 (m, 8H), 1.48 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 170.37, 158.48, 130.22, 129.77, 126.97, 121.33, 111.27, 66.35, 64.21, 38.44, 20.05, 13.40.

(2-ethoxy-5-(isoindoline-2-carbonyl)phenyl)methanaminium trifluoroacetate (9):

See Procedure D: Step 1: 40 mg (0.13 mmol) of 4, 70 mg (0.13 mmol, 1.0 eq.) of PyBOP, 22 mg (0.14 mmol, 1.1 eq.) of isoindoline hydrochloride, 150 μL (138 mg, 1.4 mol, 10.4 eq.) of NMM, and 4 mL of DMF. Step 2: 2 mL of dioxane and 0.2 mL conc. HCl. Compound 9 (39 mg, Yield=73 %) was isolated as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.74 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.35 – 7.25 (m, 2H), 7.23 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.96 (s, 2H), 4.88 (s, 5H), 4.26 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 4.18 (s, 2H), 1.50 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 170.15, 158.61, 136.31, 135.58, 130.08, 129.61, 128.19, 127.51, 127.33, 122.44, 122.15, 121.20, 111.20, 64.24, 54.70, 52.29, 38.49, 13.43.

(2-ethoxy-5-(1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-2-carbonyl)phenyl)methanaminium trifluoroacetate (10):

See Procedure D: Step 1: 26 mg (0.085 mmol) of 4, 44 mg (0.085 mmol, 0.99 eq.) of PyBOP, 20 μL (21 mg, 0.16 mmol, 1.9 eq.) of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline, 90 μL (83 mg, 0.82 mmol, 9.6 eq.) of NMM, and 4 mL of DMF. Step 2: 2 mL of dioxane and 0.2 mL conc. HCl. Compound 10 (22 mg, Yield=61 %) was isolated as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, 50 °C, Methanol-d4) δ 7.54 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 4H), 7.07 (s, 1H), 4.74 (s, 2H), 4.25 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 4.17 (s, 2H), 3.81 (s, 2H), 2.93 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 1.49 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, 50 °C, Methanol-d4) δ 158.48, 134.19, 132.61, 129.93, 129.54, 128.32, 127.96, 126.54, 126.15, 121.39, 111.44, 64.33, 38.61, 13.38.

(5-(benzylcarbamoyl)-2-ethoxyphenyl)methanaminium trifluoroacetate (11):

See Procedure D: Step 1: 30 mg (0.098 mmol) of 4, 52 mg (0.10 mmol, 1.02 eq.) of PyBOP, 20 μL (20 mg, 0.183 mmol, 1.86 eq.) of benzylamine, 110 μL (101 mg, 1.00 mmol, 10.2 eq.) of NMM, and 4 mL of DMF. Step 2: 2 mL of dioxane and 0.2 mL conc. HCl. Compound 11 (27 mg, Yield=69 %) was isolated as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.94 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.35 – 7.22 (m, 5H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 4.57 (s, 2H), 4.23 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 4.15 (s, 2H), 1.48 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 167.60, 159.69, 138.80, 130.02, 129.99, 128.10, 127.15, 127.09, 126.78, 126.77, 126.40, 121.10, 111.07, 64.29, 43.12, 38.63, 13.40.

(5-(benzyl(methyl)carbamoyl)-2-ethoxyphenyl)methanaminium trifluoroacetate (12):

See Procedure D: Step 1: 30 mg (0.098 mmol) of 4, 52 mg (0.10 mmol, 1.02 eq.) of PyBOP, 20 μL (19 mg, 0.155 mmol, 1.58 eq.) of N-methylbenzylamine, 110 μL (101 mg, 1.00 mmol, 10.2 eq.) of NMM, and 4 mL of DMF. Step 2: 2 mL of dioxane and 0.2 mL conc. HCl. Compound 12 (28 mg, Yield=69 %) was isolated as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, 50 °C, Methanol-d4) δ 7.53 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.39 – 7.19 (m, 5H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.68 (s, 2H), 4.23 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 4.15 (s, 2H), 2.97 (s, 3H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, 50 °C, Methanol-d4) δ 158.31, 136.67, 129.84, 129.54, 129.48, 128.41, 128.12, 127.27, 121.29, 111.39, 64.31, 38.63, 13.38.

(S)-1-((2-ethoxy-5-(pyrrolidin-1-ylmethyl)benzyl)amino)-3-(4-hydroxy-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-1-oxopropan-2-aminium trifluoroacetate (13):

See Procedure E and F: 32 mg (0.088 mmol) of 5, 320 μL (0.64 mmol, 7.25 eq.) of 2 M BH3*Me2S in THF, and 4 mL of THF. Step 1 of F: 155 μL (115 mg, 0.89 mmol, 10.1 eq.) of N,N-diisopropylethylamine, 52 mg (0.10 mmol, 1.13 eq.) of PyBOP, 17 mg (0.10 mmol, 1.14 eq.) of 6-Cl-HOBt, 36 mg (0.088 mmol, 1.00 eq.) of N-Boc-O-Boc-2’,6’-dimethyl-L-tyrosine, 3+1.5 mL of DMF. Step 2 of F: 2 mL TFA and 2 mL DCM. Compound 13 (12.4 mg, Yield= 26 %) was isolated as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.67 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.34 (s, 2H), 4.39 (dd, J = 14.7, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 4.26 (q, J = 13.0 Hz, 2H), 4.15 (dd, J = 14.5, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 3.98 (p, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.91 (dd, J = 11.8, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.53 – 3.38 (m, 2H), 3.22 – 3.06 (m, 3H), 2.94 (dd, J = 13.8, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.18 (br s, 2H), 2.03 (s, 8H), 1.30 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H). No 13C Data Acquired. ESI-MS: 426.3 [M + H]+, HPLC (gradient A): Retention Time: 17.62 min.

(S)-1-((2-ethoxy-5-(piperidin-1-ylmethyl)benzyl)amino)-3-(4-hydroxy-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-1-oxopropan-2-aminium trifluoroacetate (14):

See Procedure E and F: 30 mg (0.080 mmol) of 6, 280 μL (0.56 mmol, 7.03 eq.) of 2 M BH3*Me2S in THF, and 4 mL of THF. Step 1 of F: 140 μL (104 mg, 0.80 mmol, 10.1 eq.) of N,N-diisopropylethylamine, 44 mg (0.085 mmol, 1.1 eq.) of PyBOP, 14 mg (0.083 mmol, 1.0 eq.) of 6-Cl-HOBt, 34 mg (0.083 mmol, 1.0 eq.) of N-Boc-O-Boc-2’,6’-dimethyl-L-tyrosine, 3+1.5 mL of DMF. Step 2 of F: 2 mL TFA and 2 mL DCM. Compound 14 (11 mg, Yield= 25 %) was isolated as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.73 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.35 (s, 2H), 4.36 (dd, J = 14.7, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 4.21–4.15 (m, 3H), 4.04 – 3.94 (m, 2H), 3.92 (dd, J = 11.8, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.42 (t, J = 11.9 Hz, 2H), 3.12 (dd, J = 13.7, 11.8 Hz, 1H), 3.00 – 2.90 (m, 2H), 2.87 (td, J = 13.2, 12.4, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 2.04 (s, 6H), 1.93 (d, J = 13.8 Hz, 2H), 1.83 (d, J = 13.8 Hz, 1H), 1.79 – 1.63 (m, 2H), 1.50 (qt, J = 12.8, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 1.31 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). No 13C Data Acquired. ESI-MS: 440.3 [M + H]+, HPLC (gradient A): Retention Time: 18.64 min.

(2S)-1-((5-((3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexan-3-yl)methyl)-2-ethoxybenzyl)amino)-3-(4-hydroxy-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-1-oxopropan-2-aminium trifluoroacetate (15):

See Procedure E and F: 9 mg (0.024 mmol) of 7, 220 μL (0.44 mmol, 18.3 eq.) of 2 M BH3*Me2S in THF, and 3 mL of THF. Step 1 of F: 60 μL (44 mg, 0.34 mmol, 14.3 eq.) of N,N-diisopropylethylamine, 17 mg (0.033 mmol, 1.36 eq.) of PyBOP, 6 mg (0.035 mmol, 1.47 eq.) of 6-Cl-HOBt, 14 mg (0.034 mmol, 1.42 eq.) of N-Boc-O-Boc-2’,6’-dimethyl-L-tyrosine, 3+1.5 mL of DMF. Step 2 of F: 2 mL TFA and 2 mL DCM. Compound 15 (1.0 mg, Yield=8 %) was isolated as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.38 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.34 (s, 2H), 4.39 (dd, J = 14.5, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 4.28 (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 1H), 4.15 (dd, J = 14.6, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 3.98 (qd, J = 9.4, 7.3 Hz, 2H), 3.90 (dd, J = 11.8, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.51 – 3.38 (m, 4H), 3.11 (dd, J = 13.8, 11.9 Hz, 1H), 2.94 (dd, J = 13.8, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.03 (s, 6H), 1.86 (s, 2H), 1.30 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 0.85 (q, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 0.65 (q, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H). No 13C Data Acquired. ESI-MS: 438.3 [M + H]+, HPLC (gradient A): Retention Time: 18.41 min.

(S)-1-((2-ethoxy-5-(morpholinomethyl)benzyl)amino)-3-(4-hydroxy-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-1-oxopropan-2-aminium trifluoroacetate (16):

See Procedure E and F: 27 mg (0.071 mmol) of 8, 250 μL (0.50 mmol, 7.0 eq.) of 2 M BH3*Me2S in THF, and 4 mL of THF. Step 1 of F: 130 μL (96 mg, 0.75 mmol, 10.5 eq.) of N,N-diisopropylethylamine, 38 mg (0.073 mmol, 1.0 eq.) of PyBOP, 13 mg (0.077 mmol, 1.1 eq.) of 6-Cl-HOBt, 29 mg (0.071 mmol, 0.99 eq.) of N-Boc-O-Boc-2’,6’-dimethyl-L-tyrosine, 3+1.5 mL of DMF. Step 2 of F: 2 mL TFA and 2 mL DCM. Compound 16 (12.9 mg, Yield= 33 %) was isolated as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.72 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.35 (s, 2H), 4.38 (dd, J = 14.8, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.28 (d, J = 13.1 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H), 4.17 (dd, J = 14.7, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.08 – 3.95 (m, 4H), 3.92 (dd, J = 11.8, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.73 (t, J = 12.6 Hz, 2H), 3.38 – 3.32 (m, 2H), 3.21 – 3.07 (m, 3H), 2.95 (dd, J = 13.8, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.05 (s, 6H), 1.31 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H). No 13C Data Acquired. ESI-MS: 442.3 [M + H]+, HPLC (gradient A): Retention Time: 15.94 min.

(S)-1-((2-ethoxy-5-(isoindolin-2-ylmethyl)benzyl)amino)-3-(4-hydroxy-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-1-oxopropan-2-aminium trifluoroacetate (17):

See Procedure E and F: 16 mg (0.039 mmol) of 9, Step 1 of F: 140 μL (0.28 mmol, 7.18 eq.) of 2 M BH3*Me2S in THF, and 4 mL of THF. 80 μL (59 mg, 0.46 mmol, 11.8 eq.) of N,N-diisopropylethylamine, 22 mg (0.042 mmol, 1.08 eq.) of PyBOP, 9 mg (0.053 mmol, 1.36 eq.) of 6-Cl-HOBt, 17 mg (0.042 mmol, 1.06 eq.) of N-Boc-O-Boc-2’,6’-dimethyl-L-tyrosine, 3+1.5 mL of DMF. Step 2 of F: 2 mL TFA and 2 mL DCM. Compound 17 (6.1 mg, Yield=27 %) was isolated as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.74 – 7.62 (m, 1H), 7.46 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.44 – 7.37 (m, 4H), 7.22 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.32 (s, 2H), 4.66 (s, 2H), 4.64 (s, 2H), 4.52 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 2H), 4.45 – 4.35 (m, 1H), 4.17 (dd, J = 14.5, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.07 – 3.94 (m, 2H), 3.91 (dd, J = 11.7, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.11 (dd, J = 13.5, 12.2 Hz, 1H), 2.94 (dd, J = 13.8, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.02 (s, 6H), 1.31 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). No 13C Data Acquired. ESI-MS: 474.2 [M + H]+, HPLC (gradient A): Retention Time: 22.43 min.

(S)-1-((5-((3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-2(1H)-yl)methyl)-2-ethoxybenzyl)amino)-3-(4-hydroxy-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-1-oxopropan-2-aminium trifluoroacetate (18):

See Procedure E and F: 32 mg (0.075 mmol) of 10, 270 μL (0.54 mmol, 7.16 eq.) of 2 M BH3*Me2S in THF, and 4 mL of THF. Step 1 of F: 140 μL (103 mg, 0.80 mmol, 10.6 eq.) of N,N-diisopropylethylamine, 41 mg (0.079 mmol, 1.04 eq.) of PyBOP, 15 mg (0.088 mmol, 1.17 eq.) of 6-Cl-HOBt, 33 mg (0.081 mmol, 1.07 eq.) of N-Boc-O-Boc-2’,6’-dimethyl-L-tyrosine, 3+1.5 mL of DMF. Step 2 of F: 2 mL TFA and 2 mL DCM. Compound 18 (6.3 mg, Yield=14 %) was isolated as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.78 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.36 – 7.20 (m, 4H), 7.18 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.33 (s, 2H), 4.38 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 5H), 4.17 (dd, J = 14.5, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 4.00 (p, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 3.91 (dd, J = 11.8, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (br s, 1H), 3.39 (br s, 1H), 3.24 – 3.15 (m, 2H), 3.10 (t, J = 12.7 Hz, 1H), 2.94 (dd, J = 13.8, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 2.01 (s, 6H), 1.30 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H). No 13C Data Acquired. ESI-MS: 488.3 [M + H]+, HPLC (gradient A): Retention Time: 23.36 min.

(S)-1-((5-((benzylamino)methyl)-2-ethoxybenzyl)amino)-3-(4-hydroxy-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-1-oxopropan-2-aminium trifluoroacetate (19):

See Procedure E and F: 26 mg (0.065 mmol) of 11, 230 μL (0.46 mmol, 7.04 eq.) of 2 M BH3*Me2S in THF, and 4 mL of THF. Step 1 of F: 120 μL (89 mg, 0.69 mmol, 10.5 eq.) of N,N-diisopropylethylamine, 34 mg (0.065 mmol, 1.00 eq.) of PyBOP, 11 mg (0.065 mmol, 0.99 eq.) of 6-Cl-HOBt, 30 mg (0.073 mmol, 1.12 eq.) of N-Boc-O-Boc-2’,6’-dimethyl-L-tyrosine, 3+1.5 mL of DMF. Step 2 of F: 2 mL TFA and 2 mL DCM. Compound 19 (13.5 mg, Yield= 36%) was isolated as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.69 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.54 – 7.42 (m, 5H), 7.38 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.34 (s, 2H), 4.35 (dd, J = 14.5, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 4.24 – 4.12 (m, 5H), 3.97 (dddd, J = 16.3, 9.3, 7.0, 2.4 Hz, 3H), 3.92 (dd, J = 11.8, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.10 (dd, J = 13.8, 11.7 Hz, 1H), 2.95 (dd, J = 13.8, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.03 (s, 6H), 1.30 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H). No 13C Data Acquired. ESI-MS: 462.3 [M + H]+, HPLC (gradient A): Retention Time: 22.58 min.

(S)-1-((5-((benzyl(methyl)amino)methyl)-2-ethoxybenzyl)amino)-3-(4-hydroxy-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-1-oxopropan-2-aminium trifluoroacetate (20):

See Procedure E and F: 26 mg (0.063 mmol) of 12, 220 μL (0.44 mmol, 7.18 eq.) of 2 M BH3*Me2S in THF, and 4 mL of THF. Step 1 of F: 110 μL (82 mg, 0.63 mmol, 10.0 eq.) of N,N-diisopropylethylamine, 37 mg (0.071 mmol, 1.13 eq.) of PyBOP, 11 mg (0.065 mmol, 1.03 eq.) of 6-Cl-HOBt, 28 mg (0.068 mmol, 1.09 eq.) of N-Boc-O-Boc-2’,6’-dimethyl-L-tyrosine, 3+1.5 mL of DMF. Step 2 of F: 2 mL TFA and 2 mL DCM. Compound 20 (14.4 mg, Yield= 39%) was isolated as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.50 (s, 5H), 7.39 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (s, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.35 (s, 2H), 4.53 – 4.29 (m, 3H), 4.29 – 4.11 (m, 3H), 4.05 – 3.95 (m, 2H), 3.92 (dd, J = 11.7, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.10 (dd, J = 13.6, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 2.94 (dd, J = 13.8, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.67 (s, 3H), 2.03 (s, 6H), 1.31 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). No 13C Data Acquired. ESI-MS: 476.3 [M + H]+, HPLC (gradient A): Retention Time: 23.30 min.

(S)-1-((2-ethoxy-5-(pyrrolidine-1-carbonyl)benzyl)amino)-3-(4-hydroxy-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-1-oxopropan-2-aminium trifluoroacetate (21):

See Procedure F: Step 1: 36 mg (0.099 mmol) of 5, 180 μL (133 mg, 1.03 mmol, 10.4 eq.) of N,N-diisopropylethylamine, 55 mg (0.11 mmol, 1.06 eq.) of PyBOP, 17 mg (0.10 mmol, 1.01 eq.) of 6-Cl-HOBt, 41 mg (0.10 mmol, 1.01 eq.) of N-Boc-O-Boc-2’,6’-dimethyl-L-tyrosine, 3+1.5 mL of DMF. Step 2: 2 mL TFA and 2 mL DCM. Compound 21 (9.7 mg, Yield=18 %) was isolated as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.63 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.33 (s, 2H), 4.31 (dd, J = 14.6, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 4.21 (dd, J = 14.6, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 4.01 (dtt, J = 16.3, 8.9, 6.9 Hz, 2H), 3.89 (dd, J = 11.6, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 3.59 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.52 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 3.11 (dd, J = 13.7, 11.7 Hz, 1H), 2.94 (dd, J = 13.8, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.06 (s, 6H), 1.99 (p, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 1.90 (p, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 1.32 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H). No 13C Data Acquired. ESI-MS: 440.3 [M + H]+, HPLC (gradient A): Retention Time: 25.21 min.

(S)-1-((2-ethoxy-5-(isoindoline-2-carbonyl)benzyl)amino)-3-(4-hydroxy-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-1-oxopropan-2-aminium trifluoroacetate (22):

See Procedure F: Step 1: 7 mg (0.021 mmol) of 9 as HCl salt, 40 μL (30 mg, 0.23 mmol, 10.9 eq.) of N,N-diisopropylethylamine, 14 mg (0.027 mmol, 1.28 eq.) of PyBOP, 4 mg (0.024 mmol, 1.12 eq.) of 6-Cl-HOBt, 11 mg (0.027 mmol, 1.28 eq.) of N-Boc-O-Boc-2’,6’-dimethyl-L-tyrosine, 3+1.5 mL of DMF. Step 2: 2 mL TFA and 2 mL DCM. Compound 22 (4.2 mg, Yield=41 %) was isolated as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.99 (s, 1H), 8.29 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 3H), 8.10 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.35 – 7.21 (m, 4H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.31 (s, 2H), 4.85 (s, 2H), 4.73 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.29 (dd, J = 15.3, 6.1 Hz, 1H), 4.11 – 3.99 (m, 3H), 3.82 – 3.73 (m, 1H), 2.96 (dd, J = 13.9, 11.0 Hz, 1H), 2.81 (dd, J = 14.0, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 2.07 (s, 6H), 1.30 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H). No 13C Data Acquired. ESI-MS: 488.3 [M + H]+, HPLC (gradient A): Retention Time: 32.75 min.

In Vitro Pharmacology

Cell Lines and Membrane Preparations.

All tissue culture reagents were purchased from Gibco Life Sciences (Grand Island, NY, U.S.) unless otherwise noted. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing human MOR (CHO-MOR), DOR (CHO-DOR), or KOR (CHO-KOR) were used for all in vitro assays. Cells were grown to confluence at 37 °C in 5 % CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10 % fetal bovine serum and 5 % penicillin/streptomycin. Membranes were prepared by washing confluent cells three times with ice cold phosphate buffered saline (0.9 % NaCl, 0.61 mM Na2HPO4, 0.38 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4). Cells were detached from the plates by incubation in warm harvesting buffer (20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.68 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) and pelleted by centrifugation at 1600 rpm for 3 min. The cell pellet was suspended in ice-cold 50 mM Tris- HCl buffer, pH 7.4, and homogenized with a Tissue Tearor (Biospec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK, U.S.) for 20 s. The homogenate was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. The pellet was rehomogenized in 50 mM Tris-HCl with a Tissue Tearor for 10 s, followed by recentrifugation. The final pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl and frozen in aliquots at −80 °C. Protein concentration was determined via a BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific Pierce, Waltham, MA, U.S.) using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Radioligand Competition Binding Assays.

Radiolabeled compounds were purchased from Perkin-Elmer (Waltham, MA, U.S.). Opioid ligand binding assays were performed by competitive displacement of 0.2 nM [3H]-diprenorphine (250 μCi, 1.85 TBq/mmol) by the peptidomimetic from membrane preparations containing opioid receptors as described above. The assay mixture, containing membranes (20 μg protein/tube) in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4), 0.2 nM [3H]-diprenorphine, and various concentrations of test peptidomimetic, was incubated at room temperature on a shaker for 1 h to allow binding to reach equilibrium. The samples were rapidly filtered through Whatman GF/C filters using a Brandel harvester (Brandel, Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.) and washed three times with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4. Bound radioactivity on dried filters was determined by liquid scintillation counting, after saturation with EcoLume liquid scintillation cocktail, in a Wallac 1450 MicroBeta (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, U.S.). Nonspecific binding was determined using 10 μM naloxone. The results presented are the mean ± standard error (S.E.M.) from at least three separate assays performed in duplicate. Ki (nM) values were calculated using nonlinear regression analysis to fit a logistic equation to the competition data using GraphPad Prism, version 6.0c, (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

[35S]-GTPγS Binding Assays.

Agonist stimulation of [35S]guanosine 5′-O-[γ- thio]triphosphate ([35S]-GTPγS, 1250 Ci, 46.2 TBq/mmol) binding to G protein was measured as described previously.34 Briefly, membranes (10 μg of protein/well) were incubated for 1 h at 25°C in GTPγS buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) containing 0.1 nM [35S]-GTPγS, 30 μM guanosine diphosphate (GDP), and varying concentrations of test peptidomimetic. G protein activation following receptor activation by peptidomimetic was compared with 10 μM of the standard compounds [D-Ala2-N-Me-Phe4-Gly-ol]-enkephalin (DAMGO) at MOR, [D-Pen2-D-Pen5]enkephalin (DPDPE) at DOR, or U69,593 at KOR. The reaction was terminated by vacuum filtration through GF/C filters that were washed 5 times with GTPγS buffer. Bound radioactivity was measured as described above. The results are presented as the mean ± standard error (S.E.M.) from at least three separate assays performed in duplicate; potency (EC50 (nM)) and percent stimulation were determined using nonlinear regression analysis with GraphPad Prism 6, as above.

Computational Modeling

Modeling of three-dimensional (3D) structures of receptor-ligand complexes was based on available X-ray structures of the mouse MOR (PDB IDs: 4dkl_A35 and 6ddf_R36) and the human KOR (PDB IDs: 4djh_B37 and 6b73_A33) in the inactive and active conformations, respectively, and the human DOR in the inactive conformation (PDB ID: 4rwa_B38). Structures of peptidomimetic ligands were generated using the 3D-Builder Application of QUANTA (Accelrys, Inc) followed by Conformational Search included in the program package. Low-energy ligand conformations (within 2 kcal/mol) that demonstrated the best superposition of aromatic substituents of the ligand core with the pharmacophore elements (Tyr1and Phe3) of receptor-bound conformations of cyclic tetrapeptides39 were selected for docking into the receptor binding pocket. Ligands were positioned inside the receptor binding cavity to reproduce the binding modes of cyclic tetrapeptides and co-crystalized ligands in MOR, DOR, and KOR X-ray structures. The docking pose of each ligand was subsequently refined using the solid docking module of QUANTA.

Mouse Liver Microsome Stability Assays

All liver microsome assays were performed by Quintara Biosciences. Metabolic stability of testing compounds was evaluated using mouse liver microsomes to predict intrinsic clearance. Mouse liver microsome tissue fractions were obtained from Corning or Bioreclamation IVT. The assay was carried out in 96-well microtiter plates at 37 °C. Reaction mixtures (25 μL) contained a final concentration of 1 μM test compound, 0.1 mg/mL liver microsome protein, and 1 mM NADPH in 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4 buffer with 3 mM MgCl2. At each of the time points (0, 15, 30, and 60 minutes), 150 μL of quench solution (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) with internal standard (bucetin) was transferred to each well. Verapamil was included as a positive control to verify assay performance. Plates were sealed, vortexed, and centrifuged at 4°C for 15 minutes at 4000 rpm. The supernatant was transferred to fresh plates for LC/MS/MS analysis. All samples were analyzed on LC/MS/MS using an AB Sciex API 4000 instrument, coupled to a Shimadzu LC-20AD LC Pump system. Analytical samples were separated using a Waters Atlantis T3 dC18 reverse phase HPLC column (20 mm × 2.1 mm) at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The mobile phase consists of 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B). The extent of metabolism was calculated as the disappearance of the test compound, compared to the 0-min time incubation. Initial rates were calculated for the compound concentration and used to determine T1/2 values.

Animals and In Vivo Solutions

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the US National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.40 Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.41,42 Mice were group-housed with a maximum of five animals per cage in clear polypropylene cages with corn cob bedding and nestlets as enrichment. Mice always had free access to food and water. Animals were housed in pathogen-free rooms maintained between 68 and 79 °F and humidity between 30 and 70 % humidity with a 12 h light/dark cycle with lights on at 07:00 h. Experiments were conducted in the housing room during the light cycle. All studies utilize male C57BL/6 mice from Envigo laboratories, and six wild type mice weighing between 20–30 g at 7–15 weeks old, were used for behavioral experiments. All drug solutions were injected at a volume of 10 ml/kg. All drugs were dissolved in 1:9 DMSO:saline solution except for morphine sulphate and 0.6 % acetic acid which were dissolved in saline and water, respectively. All drugs were given sc. except for 0.6 % acetic acid which was given ip.

Acetic Acid Stretch Assay (AASA)

Antinociceptive effects were evaluated in the mouse acetic acid stretch assay or writhing assay. Mice received an injection of 0.6% acetic acid ip and, 5 min after this injection, the number of stretches were recorded for 20 min. Stretches were characterized by constriction of the abdomen followed by extension of the hind limbs. All analogues were given sc. 30 min prior to acetic acid. For antagonism studies, a dose of 10 mg/kg naloxone was administered ip. 15 min. before administration of a 10 mg/kg test compound. Statistical comparison of the number of stretches recorded were assessed using a two-way ANOVA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by NIH grant DA003910 (H.I.M, and J.R.T). S.P.H. was supported by the Substance Abuse Interdisciplinary Training Program administered by NIDA (T32 DA007281). J.P.A. was supported by grant DA048129. I.D.P. was supported by the NSF Division of Biological Infrastructure (award 1855425).

Abbreviations Used:

- AASA

acetic acid stretch assay

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

- BH3*Me2S

borane-dimethyl sulfide complex

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- 6-Cl-HOBt

6-chloro-1-hydroxybenzotriazole

- DAMGO

[D-Ala2-N-Me-Phe4-Gly-ol]-enkephalin

- DI

deionized

- DiBocDMT

N-Boc-O-Boc-2’,6’-dimethyl-L-tyrosine

- DIEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium

- DMT

2’,6’-dimethyl-L-tyrosine

- DNS

does not stimulate

- DOR

δ-opioid receptor

- DPDPE

[D-Pen2-DPen5]enkephalin

- EtBr

ethyl bromide

- GTPγS

guanosine 5′-O-[γ- thio]triphosphate

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- KOR

κ-opioid receptor

- MLM

mouse liver microsome

- MOR

μ-opioid receptor

- NLX

naloxone

- NMM

N-methyl morpholine

- PyBOP

benzotriazol-1-yloxytripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- THIQ

1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline

- THQ

1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This document is confidential and is proprietary to the American Chemical Society and its authors. Do not copy or disclose without written permission. If you have received this item in error, notify the sender and delete all copies.

Supporting Information:

Molecular Formula Strings (CSV)

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- (1).Fundytus ME; Schiller PW; Shapiro M; Weltrowska G; Coderre TJ Attenuation of Morphine Tolerance and Dependence with the Highly Selective δ-Opioid Receptor Antagonist TIPP[Ψ]. Eur. J. Pharmacol 1995, 286, 105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Abdelhamid EE; Sultana M; Portoghese PS; Takemori AE Selective Blockage of Delta Opioid Receptors Prevents the Development of Morphine Tolerance and Dependence in Mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1991, 258 (1), 299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hepburn MJ; Little PJ; Gingras J; Kuhn CM Differential Effects of Naltrindole on Morphine-Induced Tolerance and Physical Dependence in Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1997, 281 (3), 1350–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zhu Y; King MA; Schuller AGP; Nitsche JF; Reidl M; Elde RP; Unterwald E; Pasternak GW; Pintar JE Retention of Supraspinal Delta-like Analgesia and Loss of Morphine Tolerance in δ Opioid Receptor Knockout Mice. Neuron 1999, 24 (1), 243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kest B; Lee CE; McLemore GL; Inturrisi CE An Antisense Oligodeoxynucleotide to the Delta Opioid Receptor (DOR-1) Inhibits Morphine Tolerance and Acute Dependence in Mice. Brain Res. Bull 1996, 39 (3), 185–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Wells JL; Bartlett JL; Ananthan S; Bilsky EJ In Vivo Pharmacological Characterization of SoRI 9409, a Nonpeptidic Opioid Mu-Agonist/Delta-Antagonist That Produces Limited Antinociceptive Tolerance and Attenuates Morphine Physical Dependence. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 2001, 297 (2), 597–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Healy JR; Bezawada P; Shim J; Jones JW; Kane MA; MacKerell AD; Coop A; Matsumoto RR Synthesis, Modeling, and Pharmacological Evaluation of UMB 425, a Mixed μ Agonist/δ Antagonist Opioid Analgesic with Reduced Tolerance Liabilities. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2013, 4, 1256–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ananthan S; Saini SK; Dersch CM; Xu H; McGlinchey N; Giuvelis D; Bilsky EJ; Rothman RB 14-Alkoxy- and 14-Acyloxypyridomorphinans: μ Agonist/δ Antagonist Opioid Analgesics with Diminished Tolerance and Dependence Side Effects. J. Med. Chem 2012, 55, 8350–8363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Schiller PW; Fundytus ME; Merovitz L; Weltrowska G; Nguyen TM; Lemieux C; Chung NN; Coderre TJ The Opioid μ Agonist/δ Antagonist DIPP-NH2[Ψ] Produces a Potent Analgesic Effect, No Physical Dependence, and Less Tolerance than Morphine in Rats. J. Med. Chem 1999, 42, 3520–3526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Mosberg HI; Yeomans L; Anand JP; Porter V; Sobczyk-Kojiro K; Traynor JR; Jutkiewicz EM Development of a Bioavailable μ Opioid Receptor (MOPr) Agonist, δ Opioid Receptor (DOPr) Antagonist Peptide That Evokes Antinociception without Development of Acute Tolerance. J. Med. Chem 2014, 57 (7), 3148–3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Anand JP; Kochan KE; Nastase AF; Montgomery D; Griggs NW; Traynor JR; Mosberg HI; Jutkiewicz EM In Vivo Effects of μ Opioid Receptor Agonist/δ Opioid Receptor Antagonist Peptidomimetics Following Acute and Repeated Administration. Br. J. Pharmacol 2018, 175, 2013–2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Váradi A; Marrone GF; Palmer TC; Narayan A; Szabó MR; Le Rouzic V; Grinnell SG; Subrath JJ; Warner E; Kalra S; Hunkele A; Pagirsky J; Eans SO; Medina JM; Xu J; Pan Y; Borics A; Pasternak GW; McLaughlin JP; Majumdar S Mitragynine/Corynantheidine Pseudoindoxyls As Opioid Analgesics with Mu Agonism and Delta Antagonism, Which Do Not Recruit β-Arrestin-2. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 8381–8397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lee PHK; McNutt RW; Chang K-J A Nonpeptidic Delta Opiold Receptor Agonist, BW373U86, Attenuates the Development and Expression of Morphine Abstinence Precipitated by Naloxone in Rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1993, 267 (2), 883–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Su Y; McNutt RW; Chang K Delta-Opioid Ligands Reverse Alfentanil-Induced Respiratory Depression but Not Antinociception. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1998, 287 (3), 815–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).O’Neill SJ; Collins MA; Pettit HO; McNutt RW; Chang K Antagonistic Modulation Between the Delta Opioid Agonist BW373U86 and the Mu Opioid Agonist Fentanyl in Mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1997, 282 (1), 271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Yamazaki M; Suzuki T; Narita M; Lipkowski AW The Opioid Peptide Analogue Biphalin Induces Less Physical Dependence than Morphine. Life Sciences. 2001, pp 1023–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Yadlapalli JSK; Ford BM; Ketkar A; Wan A; Penthala NR; Eoff RL; Prather PL; Dobretsov M; Crooks PA Antinociceptive Effects of the 6-O-Sulfate Ester of Morphine in Normal and Diabetic Rats: Comparative Role of Mu- and Delta-Opioid Receptors. Pharmacol. Res 2016, 113, 335–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Pasquinucci L; Parenti C; Turnaturi R; Aricò G; Marrazzo A; Prezzavento O; Ronsisvalle S; Georgoussi Z; Fourla D; Scoto GM; Ronsisvalle G The Benzomorphan-Based LP1 Ligand Is a Suitable MOR/DOR Agonist for Chronic Pain Treatment. Life Sci. 2012, 90 (1), 66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Yadlapalli JSK; Dogra N; Walbaum AW; Wessinger WD; Prather PL; Crooks PA; Dobretsov M Evaluation of Analgesia, Tolerance and the Mechanism of Action of Morphine-6-O-Sulfate across Multiple Pain Modalities in Sprague-Dawley Rats. Anesth. Analg 2017, 125 (3), 1021–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Turnaturi R; Aricò G; Ronsisvalle G; Parenti C; Pasquinucci L Multitarget Opioid Ligands in Pain Relief: New Players in an Old Game. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2016, 108, 211–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Anand JP; Montgomery D Multifunctional Opioid Ligands In Delta Opioid Receptor Pharmacology and Therapeutic Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp 21–51. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Mosberg HI; Yeomans L; Harland AA; Bender AM; Sobczyk-Kojiro K; Anand JP; Clark MJ; Jutkiewicz EM; Traynor JR Opioid Peptidomimetics: Leads for the Design of Bioavailable Mixed Efficacy μ Opioid Receptor (MOR) Agonist/δ Opioid Receptor (DOR) Antagonist Ligands. J. Med. Chem 2013, 56, 2139–2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wang C; McFadyen IJ; Traynor JR; Mosberg HI Design of a High Affinity Peptidomimetic Opioid Agonist from Peptide Pharmacophore Models. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett 1998, 8, 2685–2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Nastase AF; Griggs NW; Anand JP; Fernandez TJ; Harland AA; Trask TJ; Jutkiewicz EM; Traynor JR; Mosberg HI Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of Novel C-8 Substituted Tetrahydroquinolines as Balanced-Affinity Mu/Delta Opioid Ligands for the Treatment of Pain. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2018, 9, 1840–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Bender AM; Griggs NW; Anand JP; Traynor JR; Jutkiewicz EM; Mosberg HI Asymmetric Synthesis and in Vitro and in Vivo Activity of Tetrahydroquinolines Featuring a Diverse Set of Polar Substitutions at the 6 Position as Mixed-Efficacy μ Opioid Receptor/δ Opioid Receptor Ligands. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2015, 6, 1428–1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Bender AM; Griggs NW; Gao C; Trask TJ; Traynor JR; Mosberg HI Rapid Synthesis of Boc-2′,6′-Dimethyl-L-Tyrosine and Derivatives and Incorporation into Opioid Peptidomimetics. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2015, 6, 1199–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Harland AA; Pogozheva ID; Griggs NW; Trask TJ; Traynor JR; Mosberg HI Placement of Hydroxy Moiety on Pendant of Peptidomimetic Scaffold Modulates Mu and Kappa Opioid Receptor Efficacy. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2017, 8, 2549–2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Harland AA; Bender AM; Griggs NW; Gao C; Anand JP; Pogozheva ID; Traynor JR; Jutkiewicz EM; Mosberg HI Effects of N-Substitutions on the Tetrahydroquinoline (THQ) Core of Mixed-Efficacy μ-Opioid Receptor (MOR)/δ-Opioid Receptor (DOR) Ligands. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 4985–4998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Harland AA; Yeomans L; Griggs NW; Anand JP; Pogozheva ID; Jutkiewicz EM; Traynor JR; Mosberg HI Further Optimization and Evaluation of Bioavailable, Mixed-Efficacy μ-Opioid Receptor (MOR) Agonists/δ-Opioid Receptor (DOR) Antagonists: Balancing MOR and DOR Affinities. J. Med. Chem 2015, 58, 8952–8969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Nastase AF; Anand JP; Bender AM; Montgomery D; Griggs NW; Fernandez TJ; Jutkiewicz EM; Traynor JR; Mosberg HI Dual Pharmacophores Explored via Structure- Activity Relationship (SAR) Matrix: Insights into Potent, Bifunctional Opioid Ligand Design. J. Med. Chem 2019, 62, 4193–4203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Henry SP; Fernandez TJ; Anand JP; Griggs NW; Traynor JR; Mosberg HI Structural Simplification of a Tetrahydroquinoline-Core Peptidomimetic μ-Opioid Receptor (MOR) Agonist/δ-Opioid Receptor (DOR) Antagonist Produces Improved Metabolic Stability. J. Med. Chem 2019, 62, 4142–4157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Stepan AF; Mascitti V; Beaumont K; Kalgutkar AS Metabolism-Guided Drug Design. Medchemcomm 2013, 4, 631–652. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Che T; Majumdar S; Zaidi SA; Ondachi P; McCorvy JD; Wang S; Mosier PD; Rajendra U; Vardy E; Krumm BE; Han GW; Lee M; Pardon E; Steyaert J; Huang X; Strachan RT; Tribo AR; Pasternak GW; Carroll FI; Stevens RC; Cherezov V; Katritch V; Wacker D; Roth BL Structure of the Nanobody-Stabilized Active State of the Kappa Opioid Receptor. Cell 2018, 172, 55–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Traynor JR; Nahorski SR Modulation by μ-Opioid Agonists of Guanosine-5’-O-(3-[35S]Thio)Triphosphate Binding to Membranes from Human Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Cells. Mol. Pharmacol 1995, 47, 848–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Manglik A; Kruse AC; Kobilka TS; Thian FS; Mathiesen JM; Sunahara RK; Pardo L; Weis WI; Kobilka BK; Granier S Crystal Structure of the m -Opioid Receptor Bound to a Morphinan Antagonist. Nature 2012, 485, 321–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Huang W; Manglik A; Venkatakrishnan AJ; Laeremans T; Feinberg EN; Sanborn AL; Kato HE; Livingston KE; Thorsen TS; Kling RC; Granier S; Gmeiner P; Husbands SM; Traynor JR; Weis WI; Steyaert J; Dror RO; Kobilka BK Structural Insights into μ-Opioid Receptor Activation. Nature 2015, 524, 315–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Wu H; Wacker D; Mileni M; Katritch V; Han GW; Vardy E; Liu W; Thompson AA; Huang X; Carroll FI; Mascarella SW; Westkaemper RB; Mosier PD; Roth BL; Cherezov V; Stevens RC Structure of the Human κ-Opioid Receptor in Complex with JDTic. Nature 2012, 485, 327–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Fenalti G; Zatsepin NA; Betti C; Giguere P; Han GW; Ishchenko A; Liu W; Guillemyn K; Zhang H; James D; Wang D; Weierstall U; Spence JCH; Boutet S; Messerschmidt M; Williams GJ; Gati C; Yefanov OM; White TA; Oberthuer D; Metz M; Yoon CH; Barty A; Chapman HN; Basu S; Coe J; Conrad CE; Fromme R; Fromme P; Tourwe D; Schiller PW; Roth BL; Ballet S; Katritch V: Stevens RC; Cherezov V Structural Basis for Bifunctional Peptide Recognition at Human δ-Opioid Receptor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2015, 22 (3), 265–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Pogozheva ID; Przydzial MJ; Mosberg HI Homology Modeling of Opioid Receptor-Ligand Complexes Using Experimental Constraints. AAPS J 2005, 7 (2), 434–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Council NR Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th ed.; National Academies Press: Washington D.C., 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Mcgrath JC; Lilley E Implementing Guidelines on Reporting Research Using Animals (ARRIVE Etc.): New Requirements for Publication in BJP. Br. J. Pharmacol 2015, 172, 3189– [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Kilkenny C; Browne W; Cuthill IC; Emerson M; Altman DG Animal Research: Reporting in Vivo Experiments: The ARRIVE Guidelines. Br. J. Pharmacol 2010, 160, 1577– [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.